Abstract

The concern for diverticulitis often leads to the use of computed tomography (CT) scans for diagnosis. We aim to develop an ultrasound-based clinical decision rule (CDR) to confidently rule-out the disease without requiring a CT scan. We analyzed data from a prospective study of adult emergency department (ED) patients with suspected diverticulitis who underwent both bedside ultrasound (US) and CT. Patient history, physical examination, laboratory findings, and US results were used to create a CDR via a recursive partitioning model designed to prioritize sensitivity, with a loss matrix heavily penalizing false negatives. We calculated the test characteristics for this CDR (TICS-Rule) and assessed the potential reduction in CT scans and ED length of stay. Data from 149 patients (84 female; mean age 58 ± 16) were used to develop the TICS-Rule. The final model integrates US diagnosis of simple and complicated diverticulitis, along with variables of heart rate, age, history of diverticulosis, vomiting, and leukocytosis. Negative US results and a heart rate below 100 effectively excluded diverticulitis. The sensitivity increased from 54.5% (32.2–75.6) in the US alone to 100% (84.6–100%) for complicated diverticulitis in the model. The TICS-Rule missed no cases of complicated diverticulitis but one case of simple diverticulitis. The median time from ED greeting to US interpretation was 103 min (IQR 62–169), compared to 285 min (IQR 229–372) for CT. The TICS-Rule uses a combination of negative US and heart rate less thanQ1 100 to exclude diverticulitis without the need for a CT scan. Integration of the TICS-Rule offers a promising enhancement to clinical decision-making while reducing both CT use and ED length of stay.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diverticulitis is a common and recurring disease, with a rising incidence correlating with advancing patient age and increasing overall incidence over time1. Although only 4% of patients with diverticulosis on computed tomography (CT) scan or colonoscopy are estimated to develop diverticulitis, it remains a common disease given that over 50% of Americans above the age of 60 have diverticulosis2,3. Diverticular disease prevalence increases with age, ranging from 10% in those younger than 40 years old and 50–70% in those older than 804,5. Given rates of diverticulosis and subsequent diverticulitis increase with age, the absolute rates and prevalence of this disease will continue to rise as our population grows and the average age increases. Not only is diverticulitis prevalent, but complicated diverticulitis is necessary to diagnose and treat given its high mortality rates. In a large national inpatient sample, 11.7% of patients admitted for diverticulitis had complicated diverticulitis due to abscess or perforation. These complications were associated with statistically significant increases in rates of inpatient procedures, operations, procedural complications, and death during hospital stay. Notably, the mortality rate for patients with perforated diverticulitis was more than five times higher than that for those with uncomplicated disease (5.4 vs. 1.0%)6. Overall, patients with complicated diverticulitis have repeatedly been shown to have higher mortality rates compared to age-matched or uncomplicated cases1,6,7.

Nationally, the approach to diagnosis of diverticulitis recommended by the American College of Radiology is to only use CT in cases of diagnostic uncertainty. The American Gastroenterological Association advises using CT in patients with suspected new diverticulitis diagnosis those with severe presentations at risk for complications, patients with failed response to therapy, immunocompromised patients, or those considering prophylactic surgery due to recurrences8,9. Similarly, internationally as advised by the European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology, the approach to suspected diverticulitis only requires CT in cases of uncertainty or high risk10.

However, in most emergency department (ED) presentations, the potential diagnosis of acute diverticulitis often warrants a low threshold for contrast-enhanced CT scans to confirm the diagnosis, assess complications, identify those who may need further intervention, or consider important alternative diagnoses. Determining the severity of diverticulitis and risk factors for complications are essential to optimizing management pathways. Given its notable accuracy and consistency, CT has emerged as the foremost diagnostic imaging modality in patients with suspected diverticulitis11.

Multiple studies have demonstrated the feasibility and accuracy of ultrasound in the diagnosis of diverticulitis11,12,13,14,15,16,17. This suggests that the use of ultrasound in the initial evaluation of these patients may have a place in the diagnostic work up of certain patients. A meta-analysis showed comparable results between ultrasound and CT with respective sensitivities of 92% vs. 94% and specificities of 90% vs. 99%, respectively11. Notably, there is a paucity of evidence on determining the accuracy of the ultrasound in detecting diverticulitis complications including perforation, abscess formation, and obstruction. In a recent 2021 European multi-center observational study the overall sensitivity was 92.7%, but sensitivity for complicated disease was only 50%16.

The potential use of point-of-care ultrasound (US) for the diagnosis of diverticulitis in the ED has recently entered the literature via case series, single-center prospective trials, and a multi-center prospective trial14,15,17. In our prospective study from which the presented clinical decision rule (CDR) is derived, US showed a high sensitivity for detecting diverticulitis overall; however, there was a high rate of missed cases of complicated diverticulitis17. Overall, these results may suggest that US tends to overcall simple diverticulitis while potentially under-calling the not-to-miss diagnosis of complicated diverticulitis.

Therefore, relying solely on US for diagnosis may result in insufficient diagnostic accuracy, potentially leading to the overuse of antibiotics, unnecessary gastroenterology referrals and admissions, and missed complications. On the other hand, novel strategies to identify low-risk patients by performing US coupled with a decision algorithm has the potential to decrease hospital admissions, minimize the use of advanced diagnostics including ionizing radiation, and optimize resource utilization ultimately improving patient care.

To our knowledge, no CDR exists for suspected diverticulitis. The development of such a rule that does not rely on CT scans may have monumental effects on healthcare utilization. This is the first study to develop a CDR for diverticulitis and to quantify the time-saving effect this protocol could have for patients with suspected diverticulitis. This would benefit our patients by reducing ionizing radiation, intravenous contrast use, and ED length of stay (LOS). This practice has further system benefits, which include reductions in healthcare costs and ED overcrowding.

The primary goals of this investigation were (1) To develop an US-based CDR to rule out diverticulitis without CT, and (2) To quantify the potential time-saving impact on ED LOS through CT scan reduction. We hypothesized that integrating history, physical examination, and laboratory findings with US could augment clinical decision-making resulting in decreased CT utilization and ED LOS.

Methods

Study design and setting

The derivation and internal validation of the CDR were obtained from a prospective study of patients with suspected diverticulitis presenting to an urban academic ED with 117,000 annual patient visits over a nineteen-month study period17. The ED is a level-1 trauma center, referral burn center, and stroke center which sees both adult and pediatric patients. The ED hosts an emergency medicine residency and an emergency ultrasound fellowship program. All ED patients are staffed by an attending physician, and most are also seen by a midlevel (resident or advanced practice practitioner) provider. This study was approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Review Board (2019P001032). All research conducted in this study was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and all patients included in the study provided informed consent.

Patients were enrolled via convenience sampling when physician and Advanced Practice Practitioner (APP) sonographers with training in the TICS protocol for diverticulitis were available17. Physician and APP sonographers included emergency ultrasound faculty who had completed one year of emergency ultrasound fellowship training, current emergency ultrasound fellows, and EM APPs with extensive emergency ultrasound training. All sonographers were blinded to the CT results performed and interpreted US scans. Sonographers had extensive background training in more standard US modalities through their emergency ultrasound training. They were trained to perform the TICS scans via a 1-hour didactic on reviewing the protocol and various images of pathologies followed by three precepted TICS scans in the ED.

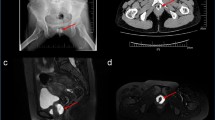

Ultrasound scanning

Patients were scanned in the supine position with both curvilinear and linear transducers. The main points of reference were the left superior iliac spine and the left side of the bladder, in which a midpoint between these two structures marked a high-yield scanning region to identify the sigmoid colon. The sigmoid colon was followed in transverse and longitudinal planes until it met the descending colon in the left iliac fossa. US findings encompassed colonic wall thickness greater than 4 mm (T), the presence of intramural air in the diverticulum indicating its location (I), compression tenderness known as the Colonic Murphy sign (C), and hyperechoic pericolic fat stranding (S). All criteria aside from compression tenderness had to be present to be interpreted as diverticulitis. The presence of pericolic fluid collections or extensive extraluminal air were considered signs of perforation and/or abscess and thus complicated diverticulitis. All US interpretations were recorded in real time.

CT scan protocol

All patients underwent abdomen and pelvis CT examinations performed in the ED using multidetector scanners (Somatom Force, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany or Discovery CT750 HD, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). In 84% (125/149) of cases the scan was performed with intravenous iodinated contrast material, using 80 mL of iohexol (Omnipaque 350, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) at a flow rate of 3 mL/s following by 40 mL saline chaser at a rate of 3 mL/s. Unless the provider requested an arterial phase study, the portal venous phase was used for all patients. The remaining 16% (14/149) or patients underwent non-contrast enhanced CT. Image acquisition was performed in helical mode from dome of the liver to 2 cm below ischial tuberosities. Imaging parameters for the Discovery CT750 HD scanner were 120 kVp, auto mA with a noise index of 20, pitch factor of 0.98, and 0.5-second rotation time. The images were reconstructed in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes with 5-mm slice thickness and using 40% ASIR V. Imaging parameters for the Somatom Force scanner were Care kV (ref kV: 120), CareDose 4D (Quality ref mAs: 220), pitch factor of 1.1, and 0.5-second rotation time. The images were reconstructed in axial, coronal, and sagittal planes with 5-mm slice thickness and using ADMIRE strength of 3. All images were available for evaluation on an PACS workstation (Visage PACS, Visage imaging, San Diego, CA). CT scans were all read by a board-certified radiology attending.

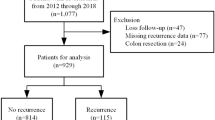

Selection of participants

For this disease process which typically affects adults, eligible patients were at least 18 years old and presented to the ED with abdominal pain suspected by the treating physician to potentially be related to acute diverticulitis and planned for diagnostic CT of the abdomen and pelvis. Exclusion criteria included: a recent diagnosis of diverticulitis confirmed by imaging within 24 h of ED presentation, pregnancy, patients deemed too unstable by treating physician, history of colon resection, and patients who were unable to consent.

Methods of measurement

Before the performance of the US, the treating attending physician was asked to determine the pre-test probability of diverticulitis with a range of 0–4 (0 = zero, 1 = very low, 2 = low, 3 = moderate, and 4 = high pre-test probability). The treating physician was not blinded to patient history or examination but to US and CT results (which were not yet available).

US interpretation was determined by the physician sonographer (not the treating physician), blinded to the patient’s medical record, laboratory findings, CT images and results, and final diagnosis. US interpretation was reported as negative, positive, or indeterminate for all subjects. Research associates extracted laboratory studies, including inflammatory markers, lactate, and creatinine, from the electronic health record (EHR) using a predefined questionnaire. Patient predictors included age, sex, ethnicity, past medical history, history of presenting illness, and vital signs. All patients with an indeterminate US result were excluded from the analysis.

CT scans were reviewed and interpreted by attending radiologists. These interpretations served as the reference standard for diagnosing diverticulitis. The method involved detailed assessment of the CT images to identify characteristic signs of diverticulitis, such as colonic wall thickening, fat stranding, the presence of diverticula, abscess, fistula, and extraluminal gas or fluid. These findings allowed further severity stratification of patients based on the Modified Hinchey score18.

The final diagnosis and the severity of diverticulitis were extracted by study investigators who used CT findings to determine the diagnosis and the Modified Hinchey score18. Hinchey Stage was dichotomized in defining severity scores as 0-Ia classified as uncomplicated diverticulitis and Hinchey Stage Ib-IV classified as complicated diverticulitis. All previously described variables were entered into a recursive partitioning model aimed at never missing a case of complicated diverticulitis.

White blood cell (WBC) elevation was defined using the reference standard which set greater than 10 × 109/L as the upper limit of normal and was used as our cut-off. Time to imaging results by US and CT, as well as total ED LOS were extracted from the EHR for each patient.

Study data were collected and managed using a HIPAA-compliant, web-based software program, Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap, Nashville, TN)19,20.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes were the derivation and implementation of a CDR used to rule out the presence of diverticulitis through the incorporation of US and potentially related demographic and clinical factors. The methodology included using specific ultrasound criteria based on TICS protocol and identifying associated clinical indicators that, when absent, reliably exclude the diagnosis of diverticulitis.

Secondary analyses included the calculation of the potential impact of the CDR on reducing the reliance on CT and subsequently decreasing ED LOS.

Primary data analysis

All patients included in the final analysis underwent both US and CT of the abdomen and pelvis and had standard history, physical examinations, and laboratory studies performed. Using CT findings as the reference examination, US combined with standard history and laboratory studies was used to develop a CDR aimed at identifying diverticulitis, and never missing a case of complicated diverticulitis.

Patient demographics, medical history, clinician pretest probability of diverticulitis, as well as outcomes were summarized as means with standard deviations for numeric variables or counts with percentages for categorical variables. The data was further stratified by outcome – negative, simple diverticulitis, and complicated diverticulitis. Comparisons between outcomes were made by t-test, chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate.

All predictors considered for inclusion in the CDR model were acquired from the prospective cohort and are listed in supplemental Table 1. Predictors were excluded if more than 25% of the values were missing or they had near zero variance. Missing values were imputed via a bagged tree model. Numeric variables such as vital signs and lab values were replaced with binary variables representing normal and abnormal values, for example WBC > 10. This was done to simplify clinical implementation as well as reduce the likelihood of model overfitting. The set of features included for modeling were: demographics - age over 75, obese, gender; lab values - WBC > 10, lactate > 2, estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60, creatinine > 1.2; initial vital signs – heart rate (HR) > 100, respiratory rate > 20; history – diverticulosis, diverticulitis, abdominal surgery; symptoms – fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, ability to tolerate oral intake; tenderness on the exam – left lower quadrant, left upper quadrant, right lower quadrant, and suprapubic area; US findings – diagnosis of simple diverticulitis, diagnosis of complicated diverticulitis, thickened bowel loops, dilated bowel, diverticula, fat stranding, free fluid, free air, and hyperemia; and pretest probability – none to very low, low, moderate to high.

A recursive partitioning model was then trained with a loss matrix that heavily penalized false negative results. This was done to favor the sensitivity of the CDR as opposed to overall accuracy. The complexity parameter was tuned via n-1 bootstrapping 50 times at each of the five levels for optimization. The final model implemented a complexity parameter of 0.013. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values (PPVs), and negative predictive values (NPVs) were calculated for the CDR.

Secondary analyses investigated the time-saving potential of the CDR. We extracted specific times from the EHR: time of ED arrival, time of CT order, time of first US image, time of last US image, time of final CT report, and time of disposition. ED LOS was defined as the time between ED arrival to disposition. The time between the last US image and the final CT report was calculated as the potential for shortening in the ED LOS.

All patients who met CDR inclusion criteria were determined to be ruled out for complicated diverticulitis with no need for CT scans. The potential time-saving impact of this CT reduction was calculated by subtracting the time elapsed between the last US image and the final CT report.

Using the difference between the time of the first and last US images, the time of the US examination was determined. The time to CT completion was determined using the time the CT was ordered and the time of the final CT report. Comparison between the time to US interpretation and CT interpretation was made using Wilcoxon signed rank tests, with correlations between the two measures evaluated using Spearman correlation coefficients. Comparison between the elapsed time to US completion and CT completion was made using Wilcoxon signed rank tests, with correlations between the two measures evaluated using Spearman correlation coefficients. A Kaplan-Meier curve was generated to analyze time-to-image interpretation.

All analyses were performed using R statistical software (http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Characteristics of study subjects

We enrolled 149 patients (84 female; mean age 58 ± 16) in whom the criteria fit the CDR analysis. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. We found no association between a diagnosis of diverticulitis and age, gender, race, body mass index, or history of surgery. However, patients with diverticulitis had higher rates of past medical history of diverticulosis and diverticulitis, and an association was found with pre-test probability. Of the patients, 67.6% with simple diverticulitis and 22.7% with complicated diverticulitis were discharged home.

Development of the clinical decision rule

A recursive partitioning model was trained on historical, clinical, laboratory, and US features to augment the prediction accuracy weighted to prioritize the sensitivity of detecting any diverticulitis. The final model incorporated US diagnosis of simple and complicated diverticulitis, heart rate, age, history of diverticulosis, vomiting, and leukocytosis (Fig. 1). The US protocol and recursive partitioning model test characteristics are reported in Table 2. They include sensitivity of US protocol for complicated diverticulitis of 54.5% (32.2–75.6) with augmentation to 100% (84.6–100%) sensitivity in the recursive partitioning model. The overall accuracy of the CDR was 67.8% (59.7–75.2%), which exceeds the no-information rate of 49.7%. Test characteristics of the CDR for negative, simple, and complicated diverticulitis are reported in Table 2. The CDR identified all cases of complicated diverticulitis and only misclassified one case of simple diverticulitis as negative; this patient was discharged and did not return within 31 days.

The CDR to exclude diverticulitis included negative US results and HR < 100, a rule which we titled the TICS-Rule (Fig. 2). Often in casual medical lingo, the term “tics” is used to refer to diverticular sacs. We adopted “TICS” as an acronym for this protocol for ease of learning and mnemonic purposes, as “TICS” represents the key features of US findings in diverticulitis: colonic wall thickness greater than 4 mm (T), the presence of intramural air in the diverticulum (I), compression tenderness known as the Colonic Murphy sign (C), and hyperechoic pericolic fat stranding (S).

Of the 34% (50) of patients who were TICS-Rule negative only one had simple diverticulitis and there were no cases of missed complicated diverticulitis. Relevant alternative diagnoses with higher prevalence included colitis or proctitis 14% (7), diverticulosis 12% (6), nephrolithiasis 12% (6), small bowel obstruction or ileus 8% (4), epiploic appendagitis 6% (3), biliary ductal dilation 6% (3), and increased stool burden 4% (2). Overall, 73% (37) of these patients were ultimately discharged, 12% (6) were placed in ED observation, and 16% (8) were admitted.

Potential time and CT saving analysis

The time from ED arrival to the interpretation of either US or CT images is depicted in Fig. 3. The median time from ED presentation to US completion was 103 min (IQR 62–169) compared to 285 min (IQR 229–372) for CT (p < 0.0001). The median time required to complete the US protocol was 6 min (IQR 4–8). The median time required to obtain CT results after the order was placed was 209 min (IQR 163–302). Median ED LOS was 402 (IQR 315–549). Early disposition of TICS-Rule negative patients could reduce CT use by up to 34% and ED LOS by 188 (IQR 147–274) minutes in patients with predicted negative results and an overall 64 min (IQR 50–94) over the whole cohort.

Discussion

In this study, we derived an ultrasound-based clinical decision rule, the TICS-Rule, which aims to rule out diverticulitis. This represents a significant advancement in gastrointestinal diagnostics. With a new tool such as US for diverticulitis it is important to acknowledge inherent limitations associated with the use of all diagnostic tools including US; its performance and interpretation is highly dependent on proper training. While the potential strength for the TICS-Rule and its impact on the clinical environment is large, care must be taken to assure its adoption is preceded by proper training and the development of clear training guidelines.

The TICS-Rule capitalizes on the high NPV of combined negative US for diverticulitis and HR < 100. The sensitivity and NPV of this TICS-Rule for excluding complicated diverticulitis reaches 100%, thus prioritizing safety by eliminating concerns for missed complicated diverticulitis identified in prior diverticulitis ultrasound research. The lower sensitivity of the recursive partitioning model for no diverticulitis and simple diverticulitis is a result of using a penalized method to ensure no cases of complicated diverticulitis were missed, achieving 100% sensitivity for complicated diverticulitis. Importantly when the TICS-Rule states a patient does not have diverticulitis this prediction comes with a 98.7% specificity. This means that the TICS-Rule rarely incorrectly rules out disease and is designed to never rule out disease when complicated diverticulitis exists. In our cohort, there was only one missed case of simple diverticulitis in a patient who had no complications in 30 days follow up and there were no cases of missed complicated diverticulitis.

Given such low false negative rates integration of the TICS-Rule may allow clinicians to safely reduce CT reliance without patient harm. Furthermore, a surprising finding was that, by using the TICS-Rule, providers do not need laboratory studies to rule-out diverticulitis, something which can further reduce harm related to venipuncture and ED LOS. Recognizing that laboratory and urine studies are likely still helpful from a complete clinical work up of abdominal pelvic pathologies we did not investigate further time reductions related to not waiting for lab results. In all cases, the clinician should refer back to the clinical context to determine if laboratory studies are helpful for other reasons or if additional imaging is necessary. If the patient is not TICS-Rule negative, then it remains beneficial to pursue CT in the workup of acute diverticulitis.

Considering patient-centered outcomes, this practice can minimize the risk of radiation, contrast allergy, intravenous contrast use, potential nephrotoxicity, injury and anxiety related to venipuncture, and ED LOS. In each clinical case integration of pre-test probability for disease with TICS-Rule results and other available information has the potential to safely and efficiently better guide patient management21. From a systems perspective, this practice can minimize ED LOS and advanced imaging utilization both of which lead to cumulative effects on ED overcrowding, balance of resources, strains on support staff, radiologist utilization, and billing; and overall optimize integration of US in ED practice. Furthermore, the ability of this rule to exclude the need for laboratory studies will decrease IV-related complications including thrombophlebitis, pain, anxiety, and time. Additionally, the simplicity of a rule that merely includes HR and US makes it very accessible to outpatient offices including primary care, gastroenterology, rural medicine, and urgent care making integration of the TICS-Rule very appealing in risk stratification of patients with suspected diverticulitis who are borderline for needing ED evaluation or transfer to a facility with CT capability. It is our vision that providers who often treat patients at risk for diverticulitis should be the first to begin training in diverticulitis US and implement the TICS-Rule. In particular, for cases of recurrent diverticulitis, the use of US in ruling out recurrence or even monitoring resolution may both save patients from the risks associated with cumulative radiation and reduce delayed diagnosis by rapid identification of disease.

On a similar wavelength to the findings in this study, a large multi-center retrospective review of acute diverticulitis patients developed a machine learning algorithm that achieved 88% sensitivity and 72% specificity in identifying diverticulitis patients at risk for procedural or surgical intervention or hospital mortality22. Although the focus of this study was to identify patients safe for discharge from the ED, not those who are at high risk for serious complications, the suggestion that there exists a vital sign finding that can further risk stratify patients is echoed in the presented study.

The results of this study support the idea that for suspected diverticulitis clinical integration of US and patient factors can refute diagnosis with reasonable NPV and negative likelihood ratio. Had US been the only diagnostic imaging study used for every patient who was TICS-Rule negative, over a third of patients could have avoided CT, leading to a reduction of more than three hours ED LOS. Reduction of radiation, ED LOS, and phlebotomy needs are important patient-centered outcomes offered by the integration of this decision rule. In the current age of high CT utilization for diagnostic certainty, decision algorithms such as this can greatly improve patient care and help combat systemic issues of ED overcrowding23. Although it is previously documented in the literature that CT utilization is linked to increased ED LOS, a specific quantification of potential LOS reduction through incorporation of a CDR for diverticulitis has not been previously demonstrated24.

It is our hope that with proper training decision rules such as this can better identify those patients which need advanced imaging and laboratory studies, and those that do not. Use of rules such as this offer not only patient-centered benefits including reduced referrals to CT capable EDs, radiation exposure, lab draws, and time spent in the ED, but also work to ease the overall burden on the healthcare system. Ultimately, we hope identifying patients who do not require CT and/or labs leads to more judicious use of resources, leading to improved and expedited patient care to those most in need, changes which lead to superior healthcare delivery through a systems lens.

A barrier to the widespread use of US and implementation of the TICS-Rule is the need for external validation. To our knowledge, and with extensive search, we could not find a similar study aimed at developing a CDR to rule out diverticulitis. Moreover, since US is user-dependent, the feasibility of using it as an alternative imaging modality depends on the availability of clinicians trained in the appropriate US protocol. Next steps include developing specific training protocols and understanding the learning curves associated with US for diverticulitis. Other possibilities include technological advancements such as the development of artificial intelligence algorithms to assist with accurate image interpretation. US should not replace CT scan if the patient does not meet TICS-Rule criteria or if the physician remains concerned about alternative pathologies. Therefore, the TICS-Rule should be limited to the low-risk cases with simple diverticulitis as the leading differential diagnosis. Further consideration on narrowing differential diagnoses and an adjudicated clinical assessment for a final disposition is warranted.

Limitations

There are limitations to the CDR derivation and TICS-Rule. First, the initial study design as a single-center observational analysis limits generalizability and the internal TICS-Rule derivation has not yet gone through external validation in other patient settings or when similar but different diverticulitis US protocols are performed by other sonographers. Therefore, this poses a limitation to the external validity of the study. External validation is necessary prior to safe implementation in clinical practice.

Second, it is important to acknowledge the limitations stemming from convenience sampling, where patients were selected based on the availability of US faculty (potential bias). This could potentially affect the generalizability of the findings to settings with less dedicated US training time. Furthermore, even when clinicians trained in this procedure are present in the future, their availability to perform this examination at bedside may be limited by the current state of the emergency department. For example, when the presence of the trained sonographer is required elsewhere for a critical procedure it is more feasible and potentially faster for a CT to be performed and interpreted without utilization of the TICS-Rule.

Third, our study excluded patients who were diagnosed with imaging confirmed diverticulitis within 24 h of ED presentation, currently pregnant, unstable, unable to consent, or who had a history of colon resection. This may limit the generalizability of these results to at-risk patient groups. However, we focused on using the TICS-Rule to help identify low-risk patients, not those clinically identified as sick and who likely required advanced diagnostic testing and potential surgical interventions. This protocol can most safely be utilized in lower-risk patients with more narrow differential diagnoses.

Fourth, it is likely that a portion of the TICS-Rule negative patients would still require a CT scan to further evaluate for alternative diagnoses and if the US is indeterminate then the patient is excluded from the TICS-Rule, another reason why CT scan may be pursued. This may apply even more so to patients with a higher BMI which may limit diagnostic certainty of TICS protocol. Thus, the estimated CT reduction and time savings represent an upper bound to the true estimate. On the other hand, use of the TICS-Rule does not require laboratory studies, but in our analysis, we only subtracted time required for CT scan, rather than laboratory studies and CT scan. Therefore, it is possible that ED LOS reduction was under-estimated for some patients as radiology typically requires renal function results prior to administration of IV contrast.

Fifth, not all patients in this study received IV contrast for their CT examination. Depending on adipose tissue and other factors it is possible that CT examination was more accurate for patients that received IV contrast. It has been shown that unenhanced low-dose CT has a lower accuracy than enhanced standard-dose CT for diverticulitis diagnosis, especially for complicated diseases25. While a standard-dose CT protocol was used at our institution some patients received contrast and some did not, which could lead to variabilities in CT accuracy. We did not evaluate the reasons for avoiding contrasts in the 16% of patients, but contrast allergy, existing kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30), and potential risk of nephrotoxicity may have contributed to this choice.

Lastly and perhaps most importantly, we have not evaluated the learning curve for performance and interpretation of the TICS protocol used in this study. There are large variations in learning curves between different POCUS applications with image acquisition ranges between 18 repetitions to 84 repetitions for soft tissue and aorta applications, respectively26. The level of training required to achieve scanning and interpretation proficiency for the TICS protocol is vital in order to design sufficient training curricula. EDs looking to integrate the TICS-Rule would first need to undergo training in the TICS protocol. Whole bowel US is utilized for diverticulitis protocols in other ED settings, and protocol differences may affect their accuracy. However, the learning curve for either approach has not been well studied15.

Conclusions

We developed the TICS-Rule, the first ultrasound-based decision rule for ruling out diverticulitis and reducing the need for CT scans. The TICS-Rule successfully excluded clinically significant diverticulitis in ED patients with suspected diverticulitis. Patients with a negative TICS-Rule had no cases of missed complicated diverticulitis. Integration of the TICS-Rule can enhance bedside clinical decision-making, potentially leading to reductions in both CT use and ED LOS.

Data availability

The datasets used in and generated from this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bharucha, A. E. et al. Temporal trends in the incidence and natural history of diverticulitis: A population-based study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110(11), 1589–1596. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.302 (2015).

Shahedi, K. et al. Long-term risk of acute diverticulitis among patients with incidental diverticulosis found during colonoscopy. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11(12), 1609–1613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.020 (2013).

Peery, A. F. et al. Distribution and characteristics of colonic diverticula in a United States screening population. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14(7), 980–985e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2016.01.020 (2016).

King, W. C. et al. Benefits of sonography in diagnosing suspected uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. J. Ultrasound Med. 34, 53–58 (2015).

Rodgers, P. & Verma, R. Transabdominal ultrasound for bowel evaluation. Radiol. Clin. North. Am. 5, 133–148 (2013).

Sell, N. M. et al. Delay to intervention for complicated diverticulitis is associated with higher inpatient mortality. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 25(11), 2920–2927 (2021).

Humes, D. J. et al. A population-based study of perforated diverticular disease incidence and associated mortality. Gastroenterology 136, 1198–1205 (2009).

Qaseem, A. et al. Diagnosis and management of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis: A clinical Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 175, 399–415. https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-2710 (2022).

Peery, A. F., Shaukat, A. & Strate, L. L. Aga clinical practice update on medical management of colonic diverticulitis: Expert review. Gastroenterology 160(3), 906–911e1 (2021).

Schultz, J. K. et al. European society of coloproctology: Guidelines for the management of diverticular disease of the colon. Colorectal Dis. 22(Suppl 2), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/codi.15140 (2020).

Laméris, W. et al. Graded compression ultrasonography and computed tomography in acute colonic diverticulitis: Meta-analysis of test accuracy. Eur. Radiol. 18, 2498–2511 (2008).

Helou, N., Abdalkader, M. & Abu-Rustum, R. S. Sonography: First-line modality in the diagnosis of acute colonic diverticulitis? J. Ultrasound Med. 32, 1689–1694 (2013).

Ripollés, T. et al. The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis, management and evolutive prognosis of acute left-sided colonic diverticulitis: A review of 208 patients. Eur. Radiol. 13, 2587–2595 (2003).

Shokoohi, H. et al. Utility of point-of-care ultrasound in patients with suspected diverticulitis in the emergency department. J Clin Ultrasound48(6), 337–342. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcu.22857

Cohen, A., Li, T., Stankard, B. & Nelson, M. A prospective evaluation of point-of-care ultrasonographic diagnosis of diverticulitis in the emergency department. Ann. Emerg. Med. 76(6), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.05.017 (2020).

Nazerian, P. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound integrated into clinical examination for acute diverticulitis: A prospective multicenter study. Ultraschall Med. 42(6), 614–622. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1161-0780 (2021). English.

Shokoohi, H. et al. Accuracy of TICS ultrasound protocol in detecting simple and complicated diverticulitis: A prospective cohort study. Acad. Emerg. Med. 30(3), 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14628 (2023)

Wasvary, H. et al. Same hospitalization resection for acute diverticulitis. Am. Surg. 65, 632–635 (1999).

HarrisPA et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42(2), 377–381 (2009).

Harris, P. A. et al. REDCap Consortium, The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software partners, J Biomed Inform. 2019 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Shokoohi, H. et al. Point-of-care ultrasound stewardship. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open. 1(6), 1326–1331. https://doi.org/10.1002/emp2.12279 (2020).

Klang, E. et al. Machine learning model for outcome prediction of patients suffering from acute diverticulitis arriving at the emergency department—A proof of concept study. Diagnostics 11(11), 2102. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11112102 (2021).

Bellolio, M. F. et al. Increased computed tomography utilization in the emergency department and its association with hospital admission. WestJEM 18(5), 835–845 (2017).

Gardner, R. L., Sarkar, U., Maselli, J. H. & Gonzales, R. Factors associated with longer ED lengths of stay. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 25(6), 643–650 (2007).

Thorisson, A. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of acute diverticulitis with unenhanced low-dose CT. BJS Open. 4(4), 659–665. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50290 (2020).

Blehar, D. J., Barton, B. & Gaspari, R. J. Learning curves in emergency ultrasound education. Acad Emerg Med.22(5), 574 – 82. doi: 10.1111/acem.12653. (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HS conceived of the study. LS wrote the manuscript text. ML performed data analysis. HS prepared Fig. 2. ML prepared Figs. 1 and 2; Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Table 1. LS and HS edited the manuscript as presented in its final version. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Selame, L., Loesche, M. & Shokoohi, H. Development of an ultrasound-based clinical decision rule to rule-out diverticulitis. Sci Rep 14, 26435 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78002-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78002-4