Abstract

The relationship between the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index and mortality among survivors of myocardial infarction (MI) remains understudied. This study aims to evaluate the association between the TyG index and mortality among adult MI patients in the US. Our study included 986 MI patients, sourced from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted from 1999 to 2018. Employing a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, we examined the association between the TyG index and mortality. To explore potential nonlinear relationships, we employed restricted cubic splines in our analysis. Additionally, we applied a two-piecewise Cox proportional hazards model for a more nuanced analysis of the data, using key turning points as boundaries. To validate the robustness of our research findings, we also performed subgroup analyses. During a 7,342 person-years follow-up period, 434 MI survivors succumbed to various causes, including 158 cardiovascular disease-related deaths. The study revealed a U-shaped pattern between the TyG index and mortality. At TyG index levels below the thresholds (8.85 for all-cause mortality and 9.02 for cardiovascular mortality), mortality exhibited a negative correlation with the TyG index (HR = 0.56, 95%CI 0.39–0.82; HR = 0.67, 95%CI 0.39–1.14). Conversely, mortality rates increased when the TyG index surpassed these thresholds (HR = 1.38, 95%CI 1.08–1.76; HR = 1.56, 95%CI 1.02–2.38). Furthermore, among diabetic patients, subgroup analyses demonstrated that the U-shaped pattern between the TyG index and cardiovascular mortality was particularly pronounced. Our research indicates that among MI survivors, a U-shaped pattern exists between the TyG index and mortality rates, which is particularly pronounced in the diabetic patient subgroup. The corresponding threshold values for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality are 8.85 and 9.02, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI), a severe consequence of coronary artery disease, characterized by ischemic necrosis of the myocardium. This necrosis is usually caused by severe coronary artery disease, leading to a significant reduction or interruption of blood flow in the coronary arteries1,2. Approximately 7 million people worldwide are affected by MI each year, with more than one-third of cases ending in death3,4. Therefore, MI poses a significant global health risk and economic burden. Complications arising from MI, such as heart failure, malignant arrhythmias, and ventricular aneurysms, can significantly reduce the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, it is crucial to identify risk factors associated with the prognosis of MI patients as early as possible, which underscores the importance of early intervention and management strategies in improving patient outcomes.

Insulin resistance (IR) is a well-recognized risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and plays a key role in the development of CVD. However, accurately quantifying IR has always been a challenge. The traditional gold standard—hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp technique—is not only costly but also technically demanding, limiting its application in large-scale cohort studies. The homeostasis model assessment of IR (HOMA-IR) offers another method for estimating IR, but it also has issues with high cost and poor reproducibility, affecting its reliability.

Through the combination of triglyceride (TG) and fasting plasma glucose (FPG), the triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index is a novel approach to measure IR5,6. Because of its accessible data and easy-to-use nature, the TyG index has been extensively utilized in recent years7,8,9. A multitude of studies have highlighted the reliability of the TyG index as an indicator for CVD10,11. A prospective cohort study confirmed the practicality of the TyG index in prognostic determination in patients with type 2 diabetes and MI12. Additionally, a study by Li and colleagues discovered that in patients with chronic coronary artery obstruction, the TyG index is markedly associated with cardiovascular risk13.

However, existing studies have mainly focused on the short-term mortality risk of hospitalized patients, and the association between the TyG index of MI survivors and long-term mortality risk is still unclear. This study aims to explore the connection between the TyG index of MI survivors and mortality, aiming to provide a reliable indicator for the early identification of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risks in MI survivors, in hopes of improving the long-term prognosis of these patients.

Materials and methods

Study population and design

The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) is a survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), aimed at assessing the health and nutritional status of the non-institutionalized population in the US. NHANES employs a complex sampling survey design, using sampling weights for specific populations, to collect nationally representative data from the non-institutionalized civilian population every two years. The study protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the NCHS, and all participants have provided written informed consent. For more information about NHANES, please visit its official website at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

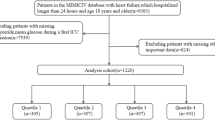

In this study, data were derived from ten consecutive NHANES cycles from 1999 to 2018, encompassing a total of 101,316 participants. Our exclusion criteria included: (1) Participants under the age of 18 or over the age of 80; (2) Pregnant participants; (3) Participants lacking basic diagnostic data for a heart attack; (4) Participants without a history of heart attack; (5) Participants missing TyG index or mortality data. The selection process is detailed in Fig. 1.

Assessment of TyG index

The calculation formula for the TyG index is as follows: TyG index = Ln [FPG (mg/L) × TG (mg/L) / 2]. The measurements of TG and FPG were performed on Roche Modular P and Roche Cobas 6000 chemical analyzers using enzymatic assays.

Diagnosis of MI

The diagnosis of MI was established using the Monetary Choice Questionnaire, which inquired, “Has someone ever informed you that you have heart attack?“14.

Ascertainment of mortality

To establish the mortality rates for the follow-up cohort, we utilized the NHANES public-use linked mortality files, last updated on December 31, 2019. The NCHS used a probabilistic matching algorithm to link this file with the National Death Index (NDI). Additionally, we identified deaths from specific diseases according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), with deaths from heart disease classified by NCHS as codes 054–068.

Covariables

Sociodemographic data were obtained through standardized household questionnaires. The questionnaires collected detailed information including age, gender, race (Mexican Americans, other Hispanic Americans, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and other races), marital status, education level, poverty income ratio (PIR), and smoking status and alcohol assumption. Marital status was categorized as unmarried (including never married, divorced, separated, or widowed individuals) and married (including those currently married and cohabiting partners). Education levels were divided into three categories: less than high school, high school or equivalent, and college or above. The household PIR was divided into four levels: < 1.3, 1.3–3, 3–5, and ≥ 5. Smoking status was defined into three categories: never smokers (individuals with less than 100 lifetime cigarettes), former smokers (those who quit after smoking at least 100 cigarettes), and current smokers (individuals who continue to smoke after reaching the 100-cigarette threshold). Drinkers were defined as participants who consumed at least 12 drinks per year. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) was determined based on the creatinine equation from the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI). Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Hypertension was defined using the following items: (1) systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg, (2) diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg, (3) taking anti-hypertensive medication, or (4) self-reported history of hypertension. Diabetes was defined as meeting any of the following criteria: (1) self-reported history of diabetes, (2) taking diabetic medication to lower blood sugar, (3) fasting plasma glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL, or (4) a hemoglobin A1c level ≥ 6.5%. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as meeting any of the following criteria: (1) self-reported history of hypercholesterolemia, (2) taking medication to lower cholesterol, or (3) a total cholesterol level ≥ 200 mg/dL.

Statistical analysis

According to NCHS guidelines, all estimates took into account the NHANES sample weights. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, while categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages. Survey-weighted linear regression models were used to compare continuous variables across different groups; whereas survey-weighted chi-square tests were applied for comparing categorical variables. Sample-weighted multivariate Cox regression analysis was employed to assess the relationship between the TyG index and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. Three adjusted regression models were established in the study: Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, and race. Model 2: further adjusted for education level, marital status, and PIR on the basis of Model 1. Model 3: on the basis of Model 2, included additional adjustments for smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI, eGFR, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia.

To explore the potential exposure-effect relationship between the TyG and mortality, a comprehensively adjusted restricted cubic spline regression method was utilized. When conducting subgroup analyses, the study assessed the potential differences in the relationship between the TyG index and mortality that might arise due to various variables, including age, sex, race, BMI, eGFR, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and diabetes.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.3.1. In the analysis, the significance level was tested using a two-tailed p-value, with values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study population

In this study, a total of 986 participants were included for the final analysis. Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of participants, categorized by TyG index quartiles. Participants in the higher quartiles of the TyG index exhibited some distinct characteristics. They were primarily males. Additionally, this group had a higher proportion of married individuals and non-Hispanic whites, but a lower level of education. Moreover, the prevalence of obesity was higher, while the prevalence of impaired kidney function was lower in this population. Among participants with higher TyG index, the prevalence of complications such as hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, angina, and stroke was also higher (all p-values < 0.05).

Association of TyG index with mortality

During a follow-up period of 7342 person-years, a total of 434 deaths were recorded, including 158 cardiovascular-related mortality cases. Subsequently, to investigate the association between the TyG index and the risk of death, four Cox regression models was applied. In our unadjusted model, the results for overall mortality were 1.00 (reference), 0.92 (0.64 to 1.32), 0.80 (0.55 to 1.16), and 1.19 (0.85 to 1.66). For cardiovascular-related deaths, the results across quartiles were 1.00 (reference), 1.21 (0.68 to 2.15), 0.78 (0.43 to 1.40), and 1.28 (0.72 to 2.28). However, after full adjustments, the multivariate-adjusted HRs and 95% CIs from lowest to highest TyG index quartile were 1.00 (reference), 0.74 (0.50 to 1.10), 0.70 (0.48 to 1.02), and 0.94 (0.63 to 1.40) respectively, for all-cause mortality; 1.00 (reference), 0.90 (0.45 to 1.78), 0.61 (0.31 to 1.19), and 0.98 (0.48 to 2.02) respectively, for cardiovascular mortality (Table 2).

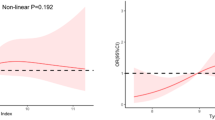

Nonlinear association between TyG index and mortality

Previous multivariate analyses demonstrated a nonlinear association between the TyG index and the risk of mortality. To precisely capture the potential patterns of this relationship, we applied a restricted cubic spline model to further analyze the link between the baseline TyG index and the risk of mortality. The study results revealed a U-shaped or nearly U-shaped association between the TyG index and cardiovascular mortality, as well as all-cause mortality (Fig. 2). To further explore the association between the TyG index and mortality risk, this study employed a two-piecewise Cox proportional hazards regression model. Based on the analysis results of the two-piecewise Cox proportional hazards regression model, we determined the inflection point values for cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality to be 9.02 and 8.85, respectively (Table 3). After adjusting for relevant covariates, for each one-unit increase in the TyG index, the risk of all-cause mortality was reduced by approximately 44%, up to the inflection point. Although cardiovascular mortality showed a downward trend before the inflection point, this decrease did not achieve statistical significance. Furthermore, when the baseline TyG index reaches the critical value, the risk of mortality is at its minimum level. However, when the TyG index exceeds 8.85 and 9.02, the risk of all-cause mortality (HR = 1.38; 95%CI 1.08–1.76) and cardiovascular mortality (HR = 1.56; 95% CI 1.02–2.38) both show a significant positive correlation.

Restricted spline curve shows the non-linear relationship between the TyG index and all-cause (A) and cardiovascular (B) mortality. Blue line and blue transparent area represent HR and 95% CI, respectively. The adjustment factors included age, sex, race, education level, Marital status, PIR, smoke, alcohol, BMI, eGFR, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia. BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimate glomerular filtration rate; PIR, Ratio of family income to poverty levels.

Stratified analyses

Details of subgroup analyses are presented in Figs. 3 and 4. For all-cause mortality, no significant interactions were found in the subgroup analysis based on factors such as age, sex, race, BMI, eGFR, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and diabetes when the TyG index is below its inflection point. However, when the TyG index exceeds its inflection point, a significant interaction was observed in the eGFR subgroup. Additionally, for cardiovascular mortality, this study found no significant interactions in the subgroup analysis based on age, sex, BMI, eGFR, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. However, significant interactions were observed in the diabetes subgroup. A significant interaction was also observed in the racial subgroup when the TyG index was below its inflection point.

Subgroup analyses of association between the TyG index and all-cause mortality. Each subgroup analysis adjusted, if not stratified, for age, sex, race, education level, Marital status, PIR, smoke, alcohol, BMI, eGFR, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimate glomerular filtration rate; PIR, Ratio of family income to poverty levels.

Subgroup analyses of association between the TyG index and cardiovascular mortality. Each subgroup analysis adjusted, if not stratified, for age, sex, race, education level, Marital status, PIR, smoke, alcohol, BMI, eGFR, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia; BMI, body mass index; eGFR, estimate glomerular filtration rate; PIR, Ratio of family income to poverty levels.

Discussion

This study reveals a novel U-shaped pattern between the TyG index of MI survivors in the US and overall mortality as well as cardiovascular-specific mortality. This relationship is characterized by an inflection point, which was observed at 8.85 for all-cause mortality and at 9.02 for cardiovascular mortality. Interestingly, this U-shaped relationship exhibited greater significance in the subset of MI survivors who have diabetes. These findings substantiate the robustness of the TyG index as a predictive factor, particularly in terms of general as well as cardiovascular mortality rates among individuals who have endured a MI.

Extensive research has highlighted the predictive potential of the TyG index for CVD10,11,15,16,17. Ma et al. suggested that the TyG index serves as a robust predictor of poor cardiovascular outcomes among diabetic patients complicated by acute coronary syndrome following percutaneous coronary intervention18. Additionally, an extensive retrospective investigation conducted in South Korea discovered that individuals with high levels of the TyG index are at a significantly increased risk of stroke and MI15. The multi-center clinical study led by Miao et al. further validated these findings. The study revealed the link between the elevated TyG index among patients with ischemic stroke and carotid atherosclerosis, supporting the role of the TyG index as a potential predictor for atherosclerosis19.

In this study, the baseline TyG index showed a significant U-shaped or nearly U-shaped association with the risk of mortality in participants with MI. Particularly in the assessment of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risks, the specific values of the TyG index, 8.85 and 9.02, were identified as significant inflection points. A one-unit increase in the baseline TyG index is associated with a roughly 44% decrease in all-cause mortality risk, until the inflection point is reached. Although there is a downward trend in cardiovascular mortality before the inflection point, this decrease does not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.39–1.14). We speculate that the sample size may have affected the statistical significance of this result. Notably, the TyG index shows a significant positive correlation with the risk of mortality once it surpasses its threshold. Furthermore, our stratified analysis results indicate that no significant interaction was observed when the TyG index was below its inflection point in the assessment of all-cause mortality. Nevertheless, a noteworthy interaction was observed within the eGFR subgroup upon surpassing the inflection point of the TyG index. We hypothesize that this may be because, in the group with poor renal function, the influence of insulin resistance on the risk of death only accounts for a small part, as the decline in renal function itself is also closely related to the risk of death. Moreover, our examination of cardiovascular mortality revealed no statistically significant interactions across subgroups defined by age, gender, BMI, eGFR, smoking status, and alcohol intake (pfor all interactions > 0.05). However, a significant interaction was observed in the diabetes subgroup, a finding consistent with the results of previous studies12,20. Additionally, it is noteworthy that a significant interaction was also observed in the racial subgroup when the TyG index was below its inflection point. This observation may be attributed to limited sample inclusivity of Hispanic participants, underscoring the necessity for future studies with robust sample sizes.

To date, the mechanism linking the TyG index to mortality remains quite complex. The link between high TyG index and increased mortality risk is primarily explained through IR, which itself is considered a key risk factor for CVD. Metabolic disorders triggered by IR, such as hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, are closely associated with adverse cardiovascular events in heart disease21. IR leads to chronic hyperglycemia and dyslipidemia, which can induce oxidative stress, intensify inflammatory responses, facilitate foam cell formation, impede vascular endothelial function, and hasten the growth of smooth muscle cells22,23. Furthermore, persistent IR can enhance the activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which may lead to retention of sodium and hypertension, thereby increasing the burden on the heart and causing damage to blood vessels and the kidneys24. Some potential mechanisms indicated that a lower TyG index could correlate with an increased mortality rate. Research evidence have shown that extremely low levels of TG or FPG are linked to adverse health outcomes and may accelerate disease progression25,26. Studies have shown that low blood sugar levels can lead to increased levels of adrenaline, which may cause platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction, thereby increasing the risk of stroke and cardiovascular events27. Additionally, a prospective cohort study has indicated that decreased serum TG levels in women correlate with a higher risk of hemorrhagic stroke28. Similarly, studies have found that low levels of TG can serve as a predictive marker for cardiac death in heart failure patients29. Furthermore, the study by Zhang et al. demonstrated a U-shaped relationship between the TyG index in patients with CVD who have diabetes or are in the prediabetes stage and their risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, suggested that both elevated and reduced TyG levels might be correlated with an adverse prognosis for these patients20. Therefore, maintaining an appropriate level of the TyG index is crucial, as extreme values of the TyG index can have adverse effects on health.

The main strengths of this study include the following points: to our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the correlation between the TyG index and mortality among MI survivors in the US. Therefore, the findings of this study enhance our understanding of the TyG index as an early identification tool for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality risks in MI survivors. Secondly, compared to previous similar studies, this study has a longer follow-up period, with a median follow-up of 78.5 months. Thirdly, although this study included only 986 patients, the use of weighted analysis methods significantly expanded the representativeness of the study. At the same time, we acknowledge that this study has some limitations. Firstly, since the study is primarily focused on the American population, caution is needed when generalizing these findings to other regions. Secondly, most of the data in the study was collected through questionnaires, which may introduce a certain degree of recall bias. Thirdly, due to the lack of electrocardiogram and imaging data, we were unable to assess the extent of myocardial damage in patients with MI, factors that are crucial for evaluating patient prognosis. Furthermore, the study did not take into account the specific treatment methods the patients received, including coronary artery bypass graft surgery or percutaneous coronary intervention, which may affect the accuracy of the study’s results.

Conclusion

Our study results confirm that the TyG index is a reliable predictor of mortality in MI patients. Furthermore, this study uncovers a nonlinear association between the TyG index and cardiovascular mortality rates, which is particularly pronounced in diabetic patients. Therefore, measuring the TyG index holds significant value for assessing the risk and predicting the prognosis of these patients.

Data availability

The dataset for this study is accessible through the NHANES online repository. The dataset is maintained by the CDC and can be publicly accessed on its official website: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm.

References

Salari, N. et al. The global prevalence of myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23 (1), 206 (2023).

Yeh, R. W. et al. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (23), 2155–2165 (2010).

Liu, X. et al. Myocardial infarction complexity: a multi-omics approach. Clin. Chim. Acta. 552, 117680 (2024).

Reed, G. W., Rossi, J. E. & Cannon, C. P. Acute myocardial infarction. Lancet (London England). 389 (10065), 197–210 (2017).

Dang, K. et al. The association between triglyceride-glucose index and its combination with obesity indicators and cardiovascular disease: NHANES 2003–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 8 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Lipid indices as simple and clinically useful surrogate markers for insulin resistance in the U.S. population. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 2366 (2021).

Liang, S. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index and coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of risk, severity, and prognosis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 (1), 170 (2023).

Guerrero-Romero, F. et al. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity. Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95 (7), 3347–3351 (2010).

Lim, J., Kim, J., Koo, S. H. & Kwon, G. C. Comparison of triglyceride glucose index, and related parameters to predict insulin resistance in Korean adults: an analysis of the 2007–2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. PloS One. 14 (3), e0212963 (2019).

Ding, X., Wang, X., Wu, J., Zhang, M. & Cui, M. Triglyceride-glucose index and the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20 (1), 76 (2021).

Chen, J., Wu, K., Lin, Y., Huang, M. & Xie, S. Association of triglyceride glucose index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 (1), 320 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Predictive effect of triglyceride–glucose index on clinical events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and acute myocardial infarction: results from an observational cohort study in China. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20 (1), 43 (2021).

Li, Y. et al. The predictive value of the triglyceride-glucose index for cardiovascular events in patients with coronary chronic total occlusion. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21 (1), 149 (2022).

Li, D. et al. The relationship between preserved ratio impaired spirometry and mortality in the myocardial infarction survivors: a population-based cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23 (1), 331 (2023).

Hong, S., Han, K. & Park, C. Y. The triglyceride glucose index is a simple and low-cost marker associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a population-based study. BMC Med. 18 (1), 361 (2020).

Wen, J. et al. Association of triglyceride-glucose index with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and mortality among familial hypercholesterolemia patients. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 15 (1), 39 (2023).

Yu, H. et al. Association between triglyceride-glucose index trajectories and carotid atherosclerosis progression. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 (1), 130 (2023).

Ma, X. et al. Triglyceride glucose index for predicting cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 19 (1), 31 (2020).

Miao, M. et al. Triglyceride-glucose index and common carotid artery intima-media thickness in patients with ischemic stroke. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21 (1), 43 (2022).

Zhang, Q., Xiao, S., Jiao, X. & Shen, Y. The triglyceride-glucose index is a predictor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in CVD patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes: evidence from NHANES 2001–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 (1), 279 (2023).

Hill, M. A. et al. Insulin resistance, cardiovascular stiffening and cardiovascular disease. Metabolism. 119, 154766 (2021).

Laakso, M. & Kuusisto, J. Insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia in cardiovascular disease development. Nat. Reviews Endocrinol. 10 (5), 293–302 (2014).

Eddy, D., Schlessinger, L., Kahn, R., Peskin, B. & Schiebinger, R. Relationship of insulin resistance and related metabolic variables to coronary artery disease: a mathematical analysis. Diabetes care. 32 (2), 361–366 (2009).

da Silva, A. A. et al. Role of Hyperinsulinemia and Insulin Resistance in hypertension: metabolic syndrome revisited. Can. J. Cardiol. 36 (5), 671–682 (2020).

Ryu, W. S., Lee, S. H., Kim, C. K., Kim, B. J. & Yoon, B. W. Effects of low serum triglyceride on stroke mortality: a prospective follow-up study. Atherosclerosis. 212 (1), 299–304 (2010).

Han, E. et al. Severe hypoglycemia increases dementia risk and related mortality: a Nationwide, Population-based Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107 (5), e1976–e1986 (2022).

Galassetti, P. & Davis, S. N. Effects of insulin per se on neuroendocrine and metabolic counter-regulatory responses to hypoglycaemia. Clinical science (London, England: 2000, 99(5):351–362. (1979).

Rist, P. M. et al. Lipid levels and the risk of hemorrhagic stroke among women. Neurology. 92 (19), e2286–e2294 (2019).

Kozdag, G. et al. Low serum triglyceride levels as predictors of cardiac death in heart failure patients. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 40 (5), 521–528 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude to the participants and staff of the NHANES for their valuable contributions. At the same time, we are grateful for the financial support provided by the Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (Grant No. QD202330).

Funding

The present study was funded by the Commission science and technology plan project of Jiangxi Provincial Health (Grant No. 202410334) and the Doctoral Research Start-up Fund Project of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (Grant No. QD202330).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJZ, LLH, WL, and MH jointly participated in the conception and design of this study. HJZ was responsible for data extraction, performing statistical analysis, and drafting the initial manuscript. HZZ and YLL provided professional academic advice and reviewed the initial draft. All authors made substantial contributions to the article and agreed unanimously on the final submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Committee. Furthermore, all NHANES participants provided written informed consent as part of the research protocol.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, HJ., Han, LL., Luo, W. et al. The triglyceride-glucose index: a predictor of mortality risk among myocardial infarction survivors. Sci Rep 14, 27512 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78056-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78056-4