Abstract

This study determined the content of metal elements (As, Cd, Cr, Hg, Pb) in 9 edible mushrooms using ICP-MS, and evaluated the harm of long-term consumption of edible mushrooms to human health. The results showed that the concentrations of metal elements decreased in the order of Cd > As > Cr > Pb > Hg in edible mushrooms. The concentrations of Cd, As, Pb, and Hg were 22.95%, 8.20%, 1.64%, and 3.28% higher, respectively, than the maximum standards in China, whereas Cr did not exceed the limit. The detection rate of metal elements in Morchella esculenta (L.) Pers (M. esculenta), and Agaricus blazei Murill (A. blazei) were relatively high. The results of single factor evaluation and target hazard coefficient (THQ, HI) indicated that Dictyophora indusiata (Vent.ex Pers) Fisch (D. indusiata), A. blazei and M. esculenta were the main sources of risk. In addition, the HI values in ascending order were: Pb (0.43) < Cr (0.68) < Hg (0.92) < Cd (7.21) < As (14.02), indicating that Cd and As were the primary sources of health risks in edible mushrooms. To ensure food safety, it is recommended to strengthen the supervision of edible mushrooms, make reasonable choices, and reduce exposure levels of heavy metal pollution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Edible fungus is a general term for a variety of edible macrofungi, which are classified as heterotrophic eukaryotes. More than 350 known edible mushrooms are known in China, including L. edodes, Agrocybe aegerita (A. aegerita), Auricularia auricula (L.ex Hook.)Underw (A. auricula), and Tremella fuciformis Berk. (T. fuciformis), which belong to basidiomycetes, and M. esculenta and Ascomycetes, which belong to ascomycetes1,2. Water content of mushrooms is around 90%. Thus, edible fungi are rich in nutrients, including protein, polypeptides, polysaccharides, minerals, and vitamins3,4,5, based on dry weight. On a whole (wet) weight various mushroom dishes (braised, grilled or from a wok) can be good source of nutrients: macro- and micro-minerals, as well as bioactive ingredients with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, such as ergosterol and phenols6,7. Although edible mushrooms are rich in nutrients and beneficial health components, they can accumulate potentially harmful trace elements8,9,10,11. Although the mineral content can be reduced after stewing, grilling, or frying, we still need to pay attention to the issue of excessive heavy metals in edible mushrooms. Metallothionein, commonly found in edible mushrooms, can specifically bind to heavy metals, causing their accumulation. Compared with vascular plants, edible mushrooms have stronger enrichment and absorption of metallic elements such as cadmium, lead, and mercury from soil and other substrates in which the mycelium lives12,13. Accumulated heavy metals, especially arsenic, cadmium, mercury or lead, can enter the human body through a contaminated mushrooms diet, leading to serious health problems, such as amnesia, blindness and deafness, kidney damage, and cancer. Thus posing a huge threat to human health. Arsenic is of special attention because of cancerous effect of some arsenicals and also is cadmium and mercury14,15,16,17,18,19. Therefore, the routine monitoring of potentially harmful trace elements in food is of great significance. However, some countries around the world lack the proper regulation of edible mushrooms, such as the European Union, which has no limits on arsenic in food20 and China’s no restrictions on chromium in edible mushrooms. Although the chromium content in wild and properly cultivated mushrooms is relatively low or very low, we may need to conduct more high-quality research on chromium in mushrooms. Research on mushroom mineral ingredients in the past has mainly focused on harmful substances that may pose a risk to mushroom consumers21, However, in addition to toxic heavy metals, the chemical forms of metallic and metalloid elements accumulated in mushrooms, an important essential mineral components and the impact of environmental pollution on the accumulation of elements, as well as culinary processing and bioavailability from a mushroom dish are of great interest22,23. China’s studies on mushrooms are still insufficient even though it is a large producer and consumer of edible mushrooms. According to previous monitoring results and literature reports, the concentrations of lead, cadmium, mercury and arsenic in edible mushrooms are higher and more toxic24,25,26. Therefore, the risk assessment of pollution factors in edible mushrooms is of great significance for food safety evaluation. The selective risk assessment of edible mushrooms in a certain area can determine whether they have a dietary exposure risk, which has guiding significance for residents’ daily consumption. The main purpose of this study was to detect and evaluate the concentrations of 5 trace elements (As, Cd, Cr, Hg, and Pb) in edible mushrooms in Shaanxi Province and explore their potential health risks.

Materials and methods

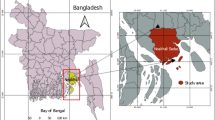

Sample collection

Representative and typical sampling locations were selected from February to September 2020 in 10 cities in Shaanxi Province (Ankang, Baoji, Hanzhong, Shangluo, Tongchuan, Weinan, Xi’an, Xianyang, Yan’an, and Yulin), including supermarkets, farmers’ markets, and small traders. Samples were collected by simple random sampling. A total of 244 samples were collected. The sample preparation process included crushing the dry sample (including 44 A. auricula, 32 T. fuciformis.) and storing it in a polyethylene plastic bottle under refrigeration. Wet samples (including 16 A. aegerita, 52 L. edodes, 32 D. indusiata, 20 H. erinaceus. 16 A. blazei, 16 P. ostreatus, 16 M. esculenta.) were processed by homogenization and stored frozen in polyethylene plastic bottles.

Instruments and reagents

An thermo (iCAP Qc) inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Thermo, USA), CEM MARS microwave digestion instrument (CEM, USA), an SL252 electronic balance (Shanghai Mingqiao Electronic Instrument Factory, China), and a Milli-Q ultrapure water meter (Merck Millipore, USA) were used, and HM100 grinding instrument(Wenling Linda Machinery Co., Ltd, China) were used in this study. Standard solutions of As, Cd, Hg, Pb and Cr were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Metrology, Nitric acid (super pure) was supplied from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagent Factory (China).

Experimental methods

Dry and wet edible fungal samples of 0.3–0.4 g and/or 0.8–1.0 g, respectively, were accurately weighed (accurate to 0.0001 g) and added to a microwave digestion tank. Nitric acid (6 mL) and 1 mL of hydrogen peroxide were added, predigested for 2 h, put into the microwave digestion instrument, and digested according to the optimized procedure. The digestion solution was brought to a constant volume of 50 mL with deionized ultrapure water. A blank control was treated similarly. The total amount of As, Cd, Hg, Pb, and Cr was determined by the ICP-MS method according to GB 5009.268–2016 National Food Safety Standard Determination of Multi Elements in Food27. Certified reference materials and parallel samples were used for quality control.

Quality control

The linearity, precision, recovery rate, limit of detection (LOD), and limit of quantification (LOQ) of each heavy metal element were detected to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the test results. The correlation coefficients (R) of the standard curves of 5 heavy metal ranged from 0.9991 to 0.9997, showing a good linear relationship within a certain range. The LOD (S/N = 3) was 0.0003–0.002 mg/kg and the LOQ (S/N = 10) was 0.001–0.006 mg/kg, as shown in Table 1. Weigh 1.000 g of blank sample separately, and then add 0.05, 0.25, and 0.75 mL of Hg standard solution with a concentration of 0.1 µg/mL, and 0.05, 0.25, and 0.75 mL of Pb, Cd, Cr and As mixed standard solution with a concentration of 1 µg/mL, respectively, to obtain low, medium, and high concentration spiked samples containing 0.1, 0.5, and 1.5 µg/L of mercury and 1, 5, and 15 µg/L of Pb, Cd, Cr and As. Process the samples according to 2.3 and inject them for analysis. Continuously measure the spiked recovery rate and relative standard deviation for 7 times. Among them, the spiked recovery rate of Pb is 93.5–100.0%, with a relative standard deviation of 0.86–1.58%; The spiked recovery rate of Cd is 94.2–98.6%, with a relative standard deviation of 0.18–6.45%; The spiked recovery rate of Cr is 97.00–101.4%, with a relative standard deviation of 0.39–3.77%; The spiked recovery rate of As is 90.1–99.5%, with a relative standard deviation of 0.27–1.98%. The spiked recovery rate of Hg is 90.0–99.5%, with a relative standard deviation of 0.39–3.27%, as shown in Table 2. The reagent and instrument blank was run frequently to eliminate the interference caused by the pollution of instruments, solvents, instruments, or chemicals used. Meanwhile, in order to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the test data, the laboratory should carry out internal quality control in the process of sample testing and carry out parallel sample detection, sample standard addition recovery test, and blind sample detection. For detailed experimental methods and quality control, please refer to another paper by the team28.

Heavy metal pollution assessment

In this study, the single-factor pollution index method and the Nemerow pollution index method were used to evaluate the degree of heavy metal pollution in edible mushrooms. Formula (1) was the calculation of the single-factor pollution index where Pi is the calculated single-pollution index of heavy metals, Ci is the measured value of heavy metals in the sample (mg kg−1), and Si is the standard limit of heavy metals in the sample (mg kg−1)(In this study, the results of A. auricula and T. fuciformis have been calculated by dry weight, while the results of other edible fungi have been calculated by wet weight29). The higher the Pi value, the higher the degree of contamination. Generally, Pi < 0.2 is a normal background value level; 0.2 ≤ Pi < 0.6 is a light pollution level; 0.6 ≤ Pi < 1 is a medium pollution level; Pi ≥ 1 is a heavy pollution level, i.e., exceeding the standard30.

The single-factor pollution index can only represent the environmental quality of a certain heavy metal and cannot reflect the contribution of environmental quality. Therefore, a comprehensive pollution index should be used to highlight the comprehensive impact of heavy metals on environmental quality. Formula (2) is the Nemerow pollution index calculation:

Where: Pave is the average value of each single factor pollution index value of the sample, and Pmax is the maximum value of each single-factor pollution index. The Nemero comprehensive pollution index values are classified as: P ≤ 0.7 is safe, 0.7 < P ≤ 1 is a warning level, 1 < P ≤ 2 is light pollution, 2 < P ≤ 3 is medium pollution, 3 < P ≤ 5 is heavy pollution, and P > 3 indicates very severe pollution30.

Health risk assessment method

The target hazard quotient (THQ) method is a health risk assessment method that can simultaneously evaluate single heavy metal and multiple heavy metal combined exposure and is a risk assessment method established by the National Environmental Protection Agency of the United States based on the average weight of adults and children31. This method assumes that the absorbed dose of pollutants is equal to the ingested dose, and the ratio of the measured human ingested dose of pollutants to the reference dose is taken as the evaluation standard. Values less than 1 indicate no obvious health risk for the exposed population; otherwise, there is a health risk32. Formulas (3) and (4) are used to calculate single heavy metal risk and multiple heavy metal compound risk, respectively.

Where: EF is exposure frequency, which is 365 days/year32; ED is the exposure range, which is 70 years; FIR is the edible fungus intake rate (122.5 g/person/day)33,34; C is the heavy metal content in edible mushrooms (unit: mg kg−1); RFD is the reference dose, where RFD (Pb) = 3.5 × 10−3 mg/(kg d), RFD (Cd) = 1 × 10−3 mg (kg d)−1, RFD (As) = 3 × 10−4mg (kg d)−1, RFD (Hg) = 3 × 10−4 mg (kg d)−1, RFD (Cr) = 3 × 10−3 mg (kg d)[−135; WAB refers to the average weight of the human body, which is 60 kg for adults; and TA refers to the average time of exposure, generally 25,550 d36.

HI is used to assess the combined risk of multiple heavy metals, where HI is the sum of the THQ of multiple heavy metals. An HI value of ≤ 1.0 indicates no significant health risk to the exposed population, 1.0 < HI < 10.0 indicates a certain health risk to the exposed population, and HI ≥ 10.0 indicates a large health risk to the exposed population.

Data processing

In this experiment, SPSS 17.0 was used for data analyses and mapping.

Results and discussion

Metal concentration in edible mushrooms

The Cd, Pb, As, Hg and Cr content in edible mushrooms and the analysis results are shown in Table 3; Fig. 1. The results showed that the content of different heavy metals in different edible mushrooms varied greatly, mainly due to the types of edible mushrooms and their cultivation characteristics37,38. Karami et al. (2020) found that the concentration of Cd, Cr, As, Hg, and Pb in the mushroom species tested was 0.001–5.89 mg kg−1, 0.32–26.32 mg kg−1, 0.003–11.50 mg kg−1, 0.16–2.24 mg kg−1, and 0.160–8.93 mg kg−139. respectively. In the samples we tested, the concentration ranges of Cd, Cr, As, Hg, and Pb were ND-2.5292 mg kg−1, 0.0230–0.5593 mg kg−1, ND-2.7739 mg kg−1, ND-0.2406 mg kg−1, and ND-1.6637 mg kg−1, respectively (Table 4). As shown in Table 4, the order of the average concentration of potentially harmful elements in edible mushrooms was Cd > As > Cr > Pb > Hg.

Cadmium

Heavy metal pollution in edible mushrooms has been reported, and cadmium pollution accounted for a large proportion. This can be due to the inherent enrichment characteristics of some varieties (or strains) or by the heavy metal pollution of water, soil, and plants caused by the disconnection between the rapid development of urban and rural economies and environmental protection measures, which makes the problem of excessive heavy metal content in some edible fungal products more prominent40,41. The China Food Safety Organization stipulates that the maximum allowable content of cadmium in edible mushrooms is 0.50 mg kg−129. In the present study, a total of 56 samples contained Cd exceeding the maximum limit specified in the national standard. The average concentration of Cd in A. blazei at 1.7274 ± 0.7441 mg kg−1(Table 3). The highest concentration in edible mushrooms was 2.5292 mg kg−1 (Table 4), which far exceeded the maximum limit specified in the national standard. Concentration ranges of Cd in edible mushrooms of 0.001–5.89 mg kg−139, 0.21–20.5 mg kg−125, 0.15–7.9 mg kg−137 were previously reported. In this study, the average concentration and concentration range of cadmium are significantly lower than those reported in the above studies.

Arsenic

The average arsenic concentration in this study was 0.1728 mg kg−1, and 12 samples had concentrations exceeding the maximum limit (0.5 mg kg−1) specified in the national standard29. A. blazei, M. esculenta, and D. indusiate had higher concentrations of arsenic than the other samples, with average concentrations of 1.2620 mg kg−1, 0.2413 mg/kg, and 0.1947 mg kg−1, respectively (Table 3). The concentrations of arsenic in edible mushrooms were reported to be 0.003–11.5 mg kg−139 and 0.008–57.34 mg kg−142, which are consistent with our research findings.

Chromium

Our testing found an average Cr concentration of 0.1165 mg kg−1 (Table 4), with M. esculenta and A. auricula having higher levels of 0.2243 mg kg−1 and 0.1627 mg kg−1 (Table 3), respectively. The results were much lower than the value of 4.2 mg kg−1 reported by Zhiqiu Fu et al.36 and 0.32–26.32 mg kg−1 reported by Hadis Karami et al.39.

Lead

Of the edible mushrooms samples analyzed, 2 samples (M. esculenta and A. blazei) exceeded the permissible Pb concentration limit in China for edible mushrooms (1.0 mg kg−1)29. The average Pb concentration in 244 edible mushrooms was 0.0624 mg kg−1 (Table 4). Previous studies reported lead concentrations in edible mushrooms of 1.09 mg kg−136 and 0.16–8.92 mg kg−139, and the average lead concentration range we measured was lower than those reported values. However, the range was consistent with the results of Sijie Liu et al.42, with a value of 0.007–1.56 mg kg−1.

Mercury

In this study, the average detected Hg concentration was 0.0148 mg kg−1. Eight samples had Hg levels in excess of the national standard permissible limit (0.1 mg kg−1)29, D. indusiata and A. blazei were the major sources of Hg exposure. Some studies have reported mercury concentrations in edible mushrooms of 1.07 mg kg−136, 0.003–0.56 mg kg−142 and 0.16–2.24 mg kg−139, which are higher than the mercury concentrations we detected.

Pollution index assessment of heavy metal

The pollution index evaluation results of different types of edible mushrooms are shown in Table 5. The single-factor evaluation results showed that the single-pollution index values of As, Cd, and Hg in A. blazei and Cd in D. indusiata and M. esculenta exceeded 1, indicating severe pollution. The Cr concentration in A. auricula, T. fuciformis, L. edodes, P. ostreatus, and M. esculenta; As concentration in L. edodes, D. indusiata, P. ostreatu, and M. esculenta; Cd concentration in L. edodes and P. ostreatus; Pb concentration in M. esculenta, and Hg concentration in D. indusiata were light pollution levels, indicating potential pollution hazards. The comprehensive pollution index value of heavy metals in A. blazei was the highest of the 9 edible mushrooms samples, indicating a moderate pollution level (P = 2.6698); the content of heavy metals in D. indusiata and M. esculenta indicated a light pollution level (P = 1.4154 and P = 1.9222, respectively), and the other edible mushrooms were at a safe level (P = 0.0431–0.2658). The results showed that the overall pollution levels in other kinds of edible mushrooms were low, except for D. indusiata and A. blazei, and that pollution in edible mushrooms with Cd might be harmful to human beings, which deserves attention. The pollution levels of As, Hg, Cd, Pb, and Cr in the same edible mushrooms were much higher than those in vegetables and fruits43.

Health risk assessment of heavy metals

The risk of the dietary intake of edible mushrooms was assessed in this study by calculating the THQ (HI). Table 6 shows that most of the THQ values of single heavy metals in the 9 edible mushrooms were less than 1, of which the THQ value for mercury in T. fuciformis was 0. In contrast, the THQ values of cadmium and arsenic in D. indusiata, A. blazei, and M. esculenta were greater than 1, consistent with the findings of Li et al.44 and Fu et al.36. The results showed that the dietary intake of heavy metals from 9 kinds of edible mushrooms was generally safe, with no dietary intake risk or low risk. However, the dietary intake of D. indusiata, A. blazei, and M. esculenta has certain health risks associated with Cd and As intake, which should be paid attention to.The analysis of the HI values of complex heavy metals in 4 edible mushrooms, including A. auricula, T. fuciformis, A. aegerita, and H. erinaceus, were less than 1.00 (0–0.70), indicating no significant health risk to the exposed population. The HI values of the four edible mushrooms of L. edodes, M. esculenta M. esculenta and P. ostreatus were all greater than 1.00 (between 1.10 and 3.60), indicating certain health risks to the exposed population, whereas the HI value of A. blazei was 12.8742, indicating a large health risk to the exposed population.

Conclusion

The results of this study showed differences in the content of heavy metals in 9 kinds of edible mushrooms, indicating that the ability of edible mushrooms to become enriched in heavy metals may be related to the strain. Most individual pollution index values were at a safe level, indicating that the overall pollution level of edible mushrooms is low. However, Cd levels in A. blazei showed heavy pollution, which is quite serious. In addition, the comprehensive pollution of A. blazei and D. indusiata is not encouraging, and the comprehensive pollution index value was far higher than that of other edible mushrooms, among which Cd was the main pollution element in A. blazei and D. indusiata. The results suggest that the supervision department should pay attention to the problem of Cd pollution in A. blazei and D. indusiata, especially in A. blazei, conduct pollution tracing investigations and research, and strengthen supervision and management of the growth, processing, and sales of edible mushrooms.

The health risk posed by heavy metals in edible mushrooms was preliminarily evaluated by the target hazard coefficient method. The THQ of heavy metals in most edible mushrooms was less than 1, indicating that a single heavy metal did not pose a significant health risk to the exposed population. The HI value of L. edoes, D. indusiata, P. ostreatus, M. esculenta, and A. blazei was greater than 1, indicating a certain degree of exposure risk for 5 types of edible mushrooms. Because the method does not consider the utilization rate of heavy metals in vivo, some bias may exsit in the findings. In addition, different forms of the elements are closely related to their toxicity. For example, inorganic As is highly toxic and carcinogenic, whereas most organic As is low toxic or non-toxic. Because some uncertainty exists in evaluating As safety based on total As, As pollution needs further analysis and research.

Nine kinds of common edible mushrooms samples were investigated in this study, and the pollution and health risks were comprehensively evaluated. The study found that the overall pollution level and health risks of edible mushrooms were within the safe range, but heavy metal pollution in A. blazei is serious and deserves our attention. Although edible mushrooms are healthy, tasty, and nutritious, they also can confer potential exposure to heavy metal pollution. Thus, strengthening the supervision of edible mushrooms and making reasonable choices to reduce heavy metal pollution exposure is needed to ensure food safety.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

References

Wei, J. et al. List of mycorrhizal edible fungi in China. Mycosystema 218, 1938–1957 (2021).

Wang, X. M. et al. A mini-review of chemical composition and nutritional value of edible wild-grown mushroom from China. Food Chem. 151, 279–285 (2014).

Su, J. et al. Determination of mineral contents of wild Boletus edulis mushroom and its edible safety assessment. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part. B. 53, 454–463 (2018).

Igbiri, S. et al. Edible mushrooms from Niger Delta, Nigeria with heavy metal levels of public health concern: A human health risk assessment. Recent Pat. Food Nutr. Agric. 9, 31–41 (2018).

Agrahar-Murugkar, D. et al. Nutritional value of edible wild mushrooms collected from the Khasi hills of Meghalaya. Food Chem. 89, 599–603 (2005).

Mary, O. et al. Chemical characterization and antioxidant potential of wild Ganoderma species from Ghana. Molecules. 22, 196 (2017).

Souilem, F. et al. Wild mushrooms and their mycelia as sources of bioactive compounds: Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic properties. Food Chem. 230, 40–48 (2017).

Radulescu, C. et al. Studies concerning heavy metals bioaccumulation of wild edible mushrooms from industrial area by using spectrometric techniques. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 84, 641–646 (2010).

Chen, X. H. et al. Analysis of several heavy metals in wild edible mushrooms from regions of China. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 83, 580–585 (2009).

Cocchi, L. et al. Heavy metals in edible mushrooms in Italy. Food Chem. 98, 277–284 (2006).

Falandysz, J. et al. Total mercury in wild-grown higher mushrooms and underlying soil from Wdzydze Landscape Park, Northern Poland. Food Chem. 81, 21–26 (2003).

Falandysz, J. et al. Mercury in fruiting bodies of dark honey fungus (Armillaria Solidipes) and beneath substratum soils collected from spatially distant areas. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 93, 853–858 (2013).

Gabriel, J. et al. Translocation of mercury from substrate to fruit bodies of Panellus Stipticus, Psilocybe Cubensis, Schizophyllum commune and stropharia rugosoannulata on oat flakes. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 125, 184–189 (2016).

Falandysz, J. et al. Toxic elements and bio-metals in Cantharellus mushrooms from Poland and China. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 24, 11472–11482 (2017).

Guissou, K. M. L. et al. Assessing the toxicity level of some useful mushrooms of Burkina Faso (West Africa). J. Appl. Biosci. 85, 7784–7793 (2015).

Järup, L. Hazards of heavy metal contamination. Br. Med. Bull. 68, 167–182 (2003).

Nordberg, G., Cadmium & Health, H. A perspective based on recent studies in China. J. Trace Elem. Exp. Med. 16, 307–319 (2003).

Liu, B. et al. Study of heavy metal concentrations in wild edible mushrooms in Yunnan Province, China. Food Chem. 188, 294–300 (2015).

Järup, L. et al. Current status of cadmium as an environmental health problem. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmcol. 238, 201–208 (2009).

Melgar, M. J. et al. Total contents of arsenic and associated health risks in edible mushrooms, mushroom supplements and growth substrates from Galicia (NW Spain). Food Chem. Toxicol. 73, 44–50 (2014).

Gast, C. H. et al. Heavy metals in mushrooms and their relationship with soil characteristics. Chemosphere 17, 789–799 (1988).

Falandysz, J. et al. Mercury in raw mushrooms and in stir-fried in deep oil mushroom meals. J. Food Compos. Anal. (2019).

Falandysz, J. et al. 137Cs, 40K, and K in raw and stir-fried mushrooms from the Boletaceae family from the Midu region in Yunnan, Southwest China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. (2020).

Xue, L. et al. Determination of content and health risks analysis of lead,cadmium, mercury, arsenic in cultivated edible fungi in Qingdao, Shandong Province. Qual. Saf. Agro-Prod. 04, 36–39 (2024).

Ye, J. et al. Determination of heavy metal content and risk assessment of edible mushrooms in Western Sichuan. Chin. J. Inorg. Anal. Chem. 14, 1272–1280 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Safety risk assessment of common wild edible fungi in Yunnan Province. Edible Fungi China 42, 21–26 (2023).

MHC. Determination of multi elements in foods, GB5009.268-2016 (Ministry Health China, 2016).

Liu, J. et al. Determination of heavy metal content in edible fungi by microwave digestion inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Edible Fungi China. 43, 65–69 (2024).

SAC. National Food Safety Standard Limits of contaminants in food (GB 2762) (National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China, 2022).

Wang, C. et al. Investigation on heavy metal contamination and distribution of edible fungi in Shaanxi Province. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 14, 284–291 (2018).

Yin, J. et al. A comparison of accumulation and depuration effect of dissolved hexavalent chromium (Cr6+) in head and muscle of bighead carp (Aristichthys Nobilis) and assessment of the potential health risk for consumers. Food Chem. 286, 388–394 (2019).

USEPA. Risk-Based Concentration Table (United States Environ. Prot. Agency, 2002).

WANG, B. H. et al. Determination and health risk evaluation of heavy metals in cultivated edible mushrooms. J. Food Saf. Qual. 7, 490–496 (2016).

Yang, T. et al. Mercury content in leccinum fungi and its health risk associated with food intake in Yunnan Province. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 11, 348–355 (2016).

USEPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency IRIS Assessments (2017).

Fu, Z. et al. Assessment of potential human health risk of trace element in wild edible mushroom species collected from Yunnan Province, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 29218–29227 (2020).

Kokkoris, V. et al. Accumulation of heavy metals by wild edible mushrooms with respect to soil substrates in the Athens metropolitan area (Greece). Sci. Total Environ. 685, 280–296 (2019).

Ivanić, M. et al. Multi-element composition of soil, mosses and mushrooms and assessment of natural and artificial radioactivity of a pristine temperate rainforest system (Slavonia, Croatia). Chemosphere 215, 668–677 (2019).

Karami, H. et al. The concentration and Probabilistic Health risk of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in Edible Mushrooms (Wild and cultivated) samples collected from different cities of Iran. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 199, 389–400 (2020).

GAO, T. Y. et al. Research status and development trend of mushroom biosorption of heavy metals. Sci. Technol. Innov. Herald 153 (2007).

Xian, Y. et al. Adsorption characteristics of cd(II) in aqueous solutions using spent mushroom substrate biochars produced at different pyrolysis temperatures. RSC Adv. 8, 28002–28012 (2018).

Liu, S. et al. Pollution level and risk assessment of lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic in edible mushrooms from Jilin Province, China. J. Food Sci. 86, 3374–3383 (2021).

Liu, S. J. et al. Research progress on the main heavy metal pollution and risk assessment of edible mushrooms. J. Food Saf. Qual. 9, 3206–3209 (2018).

LI, B. et al. Analysis of Heavy metals in dried edible fungi commercially available in Beijing and assessment of health risks via consumption. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 26, 293–299 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Xi’an Centre for Disease Control and Prevention and the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province, China (2023-YBSF-641).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guofu Qin: Writing-Original draft preparation; Guipeng Zhao and Ruixiao Liu: Contacted and collected sample materials; Pan Zhang, Fengrui He and Ting Wang: Collected and detected of the samples; Keting Zou: Funding acquisition, Data sorting and analysis; Jia Liu: Methodology, Software and Safety evaluation; Yongbo Li: Visualization of the data; Baozhong Chen: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, G., Liu, J., Zou, K. et al. Analysis of heavy metal characteristics and health risks of edible mushrooms in the mid-western region of China. Sci Rep 14, 26960 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78091-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78091-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mineral composition and bioactive components of three popular edible forest mushrooms (Cantharellus cibarius fries, Cyclocybe aegerita (V.Brig.) Vizzini and agaricus arvensis Schaeff)

Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization (2025)