Abstract

With an aging population seeking infertility treatment, diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) is a prevalent indication for assisted reproductive technology (ART). This study aims to investigate the relationship between sleep parameters and DOR among women attending an infertility clinic. Methods We consecutively enrolled women attending an infertility clinic from July 2020 to June 2021. Participants completed the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale(ESS), and STOP-Bang Questionnaire to assess self-reported sleep quality. DOR-related indices including antral follicle count, anti-Müllerian hormone(AMH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) were evaluated. A total of 979 women were enrolled, with 148 classified into the DOR group and 831 in the non-DOR group. The DOR group was notably older compared to the non-DOR group. Analysis showed that the DOR group exhibited significantly shorter sleep onset latency (p = 0.001) and shorter total sleep duration (p = 0.014) compared to the non-DOR group. Logistic regression analysis identified age, PSQI-sleep latency, and PSQI score as independent factors associated with an increased risk of DOR(all p < 0.05). Furthermore, stratified analysis by age group revealed that snoring and PSQI-sleep latency were particularly notable risk factors for DOR among women aged 35 years and older (OR = 2.489, p = 0.040; OR = 2.007, p = 0.008, respectively). Our study highlights that shorter sleep onset latency and shorter total sleep duration may be associated with DOR among women undergoing ART treatments. Particularly noteworthy, snoring and sleep latency were identified as additional risk factors for DOR among women aged 35 years and older.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reproduction, a fundamental aspect of species evolution, has exhibited remarkable conservation across time. Over the past two decades, surveys have indicated a rising trend of infertility among younger women. Factors contributing to this phenomenon include industrialization, environmental pollution, societal pressures, and various health conditions. A pivotal marker in assessing female fertility is the ovarian reserve1.

Clinicians employ several tests to evaluate ovarian reserve, encompassing biochemical assessments such as follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol (E2), inhibin B, and antimüllerian hormone (AMH), as well as ultrasound techniques like antral follicle count (AFC)23. Diminished ovarian reserve (DOR), a relatively recent appreciation within the continuum of reproductive senescence, alludes to the residual repertoire of oocytes remaining in the ovaries at a given age. According to the 2018 Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology National Summary4, DOR was the second most common reason for assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures, following egg/embryo banking, accounting for a third of all ART cycles that year. Clinically, DOR manifests as poor response to ovarian stimulation during in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles, characterized by elevated basal follicle-stimulating hormone levels, diminished antimüllerian hormone levels, and/or a low antral follicle count. Women with DOR often experience lower oocyte yields and may obtain few or no viable embryos for transfer, posing significant challenges to achieving successful live births5.

Despite extensive research, the underlying causes of DOR remain poorly understood. This complex condition is influenced by numerous factors including age, environmental exposures, the initial primordial follicular pool, diseases, medications, and other yet unidentified elements67 [1, 6]. Notably, no studies have explored the potential relationship between sleep disorders and DOR. Hence, this study aims to investigate the impact of sleep quality, assessed using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and STOP-Bang Questionnaire, on DOR. By exploring these associations, we aim to broaden our understanding of the multifaceted influences on ovarian reserve and potentially uncover new avenues for managing and preventing DOR in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Study population

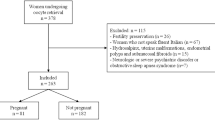

Couples seeking treatment for infertility at the Center of Reproductive Medicine, Fujian Provincial Maternity and Children’s Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University from July 2020 to June 2021 were included in this study. The data were gathered from male participants following their receipt of either IVF or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) treatments at the clinic. The study’s inclusion criteria specified couples scheduled for IVF or ICSI treatment. Exclusion criteria encompassed: (1) pregnancy or lactation; (2) hypothalamic-pituitary disease; (3) ovarian surgery history; (4) concurrent physical illnesses causing insomnia; (5) prior treatment for sleep disorders; (6) diagnosed inflammation of the urogenital system, epididymitis, testicular injury, incomplete orchiocatabasis, or varicocele. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment in the study, and the research protocols were approved by the ethics committee of Fujian Provincial Maternity and Children’s Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University.

Diagnosis and grouping

Participants were categorized into two groups based on their ovarian reserve status: DOR and non-DOR. Diagnosis of DOR required meeting at least two of the following criteria: (1) AMH < 1.2 ng/mL, (2) AFC < 7 on days 2–4 of the menstrual cycle, (3) basal serum FSH > 10 U/L8. Participants with normal ovarian reserve were classified into the non-DOR group. Hormone levels including FSH, LH, AMH, PRL, and E2 were assessed using the Chemiluminescence method. The study also involved calculating ovarian follicle distribution by color ultrasound.

Assessment of sleep quality

The PSQI, developed by Buysse, is a reliable tool that assesses sleep quality over the past month9. It comprises seven components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is rated on a scale of 0 to 3, yielding a global score ranging from 0 to 21. A PSQI score ≥ 5 indicates poor sleep quality, with a sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% for identifying sleep disorders10.

The STOP-Bang Questionnaire is employed to screen for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)11. It includes two sections with eight yes/no questions: Stop Questions (snoring, daytime tiredness, observed cessation of breathing during sleep, hypertension) and Modified Stop Questions (BMI > 35 kg/m2 (or 30 kg/m2), age > 50 years, neck circumference > 40 cm, male gender). Each affirmative response scores 1 point, resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 8, with higher scores indicating greater risk of OSA.

The ESS is an eight-item questionnaire designed to assess daytime sleepiness12. Respondents rate their likelihood of dozing off or falling asleep using a scale from 0 (never) to 3 (high chance), with scores ranging from 0 to 24. ESS scores effectively discriminate levels of daytime sleepiness across individuals.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using IBM-SPSS version 22.0. Continuous variables were first tested for normal distribution. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation(SD), and differences between groups were compared using paired t-tests. Skewed variables were presented as median (25%, 75%) and compared using Mann-Whitney tests. Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify risk factors for DOR. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

We enrolled a total of 979 women, among whom 148 were diagnosed with DOR (DOR group) with a mean age of 35.35 years, while 831 women did not have DOR (non-DOR group) with a mean age of 31.70 years (p < 0.001). Significant group differences were observed in Follicle count, AMH, FSH, E2, and T (all p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 2 compares sleep quality assessed by the PSQI, ESS, and STOP-Bang Questionnaire between the groups. The DOR group exhibited significantly shorter sleep onset latency (15 vs. 22 min, p = 0.001) and reduced total sleep duration (7.35 ± 0.93 vs. 7.57 ± 1.01 h, p = 0.014) compared to the non-DOR group. Regarding PSQI, both sleep onset latency and sleep time showed significant differences between the groups. However, there were no significant differences in ESS and STOP-Bang Questionnaire scores.

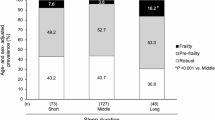

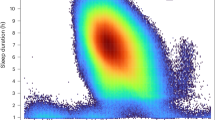

To further investigate the impact of sleep onset latency and total sleep duration on ovarian reserve, we categorized total sleep duration into > 8 h, 6–8 h, and ≤ 6 h, and sleep onset latency into < 30 min, 30–44 min, and ≥ 45 min. Significant differences were found in AMH, Follicle-Left, and Follicle-Right based on total sleep duration (p = 0.007, 0.005, 0.030, respectively), indicating higher levels in those with > 8 h of sleep compared to ≤ 6 h. Sleep onset latency also showed significant differences in AMH, Follicle-Left, and Follicle-Right (p = 0.001, 0.011, 0.036, respectively), with the 30–44 min group showing higher AMH levels compared to the other groups. Groups with ≥ 45 min of sleep onset latency exhibited higher Follicle counts compared to other groups(Fig. 1).

A logistic regression model identified age, PSQI-sleep latency, and PSQI as independent risk factors for DOR (adjusted odds ratios [OR] = 0.831, 1.708, 0.870, p < 0.001, 0.002, 0.036, respectively). Exploring subjects aged ≥ 35 years (277 subjects), snoring and PSQI-sleep latency were found to be independent risk factors for DOR (OR = 2.489, 2.007, p = 0.040, 0.008, respectively). Additionally, when stratified by BMI, in the BMI ≥ 25 kg/m² group, age was the only independent risk factor for DOR (OR = 0.822, p < 0.001), whereas in the BMI < 25 kg/m² group, both age and PSQI-sleep latency were identified as independent risk factors (OR = 0.828, 1.761, p < 0.001, 0.003, respectively) (Table 3).

Discussion

Our study investigated the relationship between sleep parameters and DOR among women at an infertility clinic. We found that shorter sleep onset latency and snoring were significantly associated with an increased likelihood of DOR in women aged 35 years and older. Specifically, women in this age group who experienced these sleep disturbances had approximately 2.489 and 2.007 times higher odds of developing DOR, respectively, compared to those without these issues, after adjusting for other variables. These findings suggest that sleep disruptions may contribute to ovarian dysfunction and potentially worsen DOR among our study participants.

As modern society continues to progress and pregnancy is increasingly delayed, DOR has become a significant challenge for women seeking pregnancy, as well as for future societal demographics13. Studies have reported varying prevalence rates of DOR among reproductive-age women, ranging from 10 to 26%, with higher incidences observed in populations undergoing ART1415. Women with DOR undergoing ART typically experience lower oocyte yields, reduced live birth rates, and higher rates of treatment discontinuation compared to those with normal ovarian reserve16. The etiology of DOR is multifaceted and includes autoimmune disorders, genetic abnormalities, environmental factors, and iatrogenic causes, although many cases remain idiopathic17. Advanced maternal age is a well-established contributor to DOR due to diminished ovarian follicular pool and oocyte quality decline18. Consistent with this understanding, our study confirmed that women in the DOR group were older than those in the non-DOR group, underscoring the impact of age on ovarian reserve.

In addition to age, our findings suggest an association between sleep disturbances and DOR. Sleep disruptions, such as inadequate sleep duration and poor sleep quality, are known to disrupt the endocrine system. These disruptions can alter the secretion of reproductive hormones crucial for ovarian function and follicular development, including FSH, LH, and AMH19. Previous research has linked insufficient sleep (< 5–6 h) to menstrual cycle20, sperm parameters21, natural fertility22, or IVF outcomes23. Gong et al.24 found that poor sleep quality independently increased the risk of both of these menstrual issues. Our study adds to this body of evidence by demonstrating that the DOR group exhibited significantly shorter total sleep duration and shorter sleep onset latency. Logistic regression analysis identified PSQI-sleep latency as an independent risk factor for DOR across all subjects, particularly in those aged 35 and older. This observation suggests that rapid sleep onset, potentially indicative of underlying sleep disorders or poor sleep quality, could serve as a marker for compromised ovarian reserve. Similarly, studies have demonstrated that insufficient sleep can negatively impact natural fertility and IVF outcomes, reinforcing our findings that sleep disruptions, such as shorter total sleep duration, may contribute to ovarian dysfunction2223.

Sleep disturbances, such as shorter sleep onset latency and snoring, disrupt both the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axes, leading to hormonal imbalances and stress-related effects that can impair ovarian function2526. Disruptions in the HPG axis affect the secretion of key reproductive hormones like FSH, LH, and AMH, which are crucial for maintaining ovarian reserve27. On the other hand, rapid sleep onset may indicate dysfunction in the HPA axis, which regulates cortisol secretion28. Chronic stress and elevated cortisol levels have been associated with ovarian dysfunction and reduced ovarian reserve, potentially accelerating ovarian aging2930. Moreover, conditions like OSA exacerbate these effects through intermittent hypoxia, increasing oxidative stress and potentially reducing ovarian reserve31. Additionally, immune dysregulation resulting from sleep loss elevates pro-inflammatory cytokines, negatively affecting ovarian health and accelerating follicular depletion32. In summary, sleep disturbances may affect ovarian reserve through multiple interconnected pathways, including neuro-endocrine and immune dysregulation, oxidative stress, and hormonal imbalances. Further research is needed to better understand these mechanisms and their contribution to DOR.

Our study also identified snoring as a specific sleep-related factor significantly associated with DOR, especially among women aged 35 years and older. Snoring often indicates OSA, a condition characterized by repeated airway collapse during sleep, leading to oxygen desaturation and fragmented sleep patterns. OSA is known to induce oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which are implicated in accelerated aging processes33. Oxidative stress is recognized as a key mechanism in ovarian aging, and antioxidants like resveratrol have been explored as effective measures to delay oocyte aging3435. Studies have shown that resveratrol, an antioxidant, has also been beneficial in treating sleep apnea patients36. Therefore, we hypothesize that chronic intermittent hypoxia and oxidative stress associated with OSA could exacerbate ovarian aging through multiple pathways, including alterations in the secretion of hormones crucial for ovarian function and follicular development.

Our findings hold significant clinical implications for women undergoing ART treatments, especially those with DOR. Identifying sleep disturbances like shorter sleep onset latency and snoring as risk factors highlights the need to include sleep assessments in infertility evaluations. Early detection of sleep issues could offer opportunities for interventions to improve reproductive outcomes. Addressing sleep disorders through behavioral or medical therapies may help preserve ovarian function and fertility. Moreover, comprehensive care for women over 35, who are at higher risk for both sleep disturbances and DOR, should include sleep hygiene education and management. Future studies should investigate whether improving sleep quality could enhance ovarian reserve or ART success, offering new treatment possibilities for women with DOR.

Despite the insights gained, our study has several limitations. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, and prospective longitudinal studies are warranted to establish temporal relationships between sleep patterns and DOR. Additionally, our findings are based on self-reported sleep assessments, which may be subject to recall bias and variation in reporting. Furthermore, we did not include measures of stress and anxiety, which are known to impact sleep quality and could have influenced the results. Future research could benefit from incorporating stress and anxiety scales, along with a control group without DOR but experiencing stress, to better differentiate the roles of these factors. Objective measures of sleep quality, such as actigraphy or polysomnography, should also be considered in future studies to provide more precise and detailed insights, particularly in relation to conditions like obstructive sleep apnea and its potential impact on ovarian reserve.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study underscores the significance of sleep parameters as potential contributors to diminished ovarian reserve in women seeking infertility treatment. Addressing sleep disturbances, especially among older women, may offer a novel approach to enhancing reproductive outcomes in clinical practice. Further investigation into the mechanistic links between sleep and ovarian function is warranted to optimize fertility treatment strategies and improve overall reproductive health outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DOR:

-

diminished ovarian reserve

- ART:

-

assisted reproductive technology

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- ESS:

-

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

- AMH:

-

anti-Müllerian hormone

- FSH:

-

follicle-stimulating hormone

- LH:

-

luteinizing hormone

- E2:

-

estradiol

- AFC:

-

antral follicle count

- IVF:

-

in vitro fertilization

- ICSI:

-

intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- OSA:

-

obstructive sleep apnea

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- NC:

-

neck circumference

- PRL:

-

prolactin

- T:

-

testosterone

- HPG:

-

hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal

- HPA:

-

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

References

Visser, J. A. et al. Anti-mullerian hormone: a new marker for ovarian function. Reproduction. 131 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep.1.00529 (2006). [published Online First: 2006/01/03].

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Electronic address aao, Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive M. Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 114 (6), 1151–1157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.09.134 (2020). [published Online First: 2020/12/08].

Tal, R. & Seifer, D. B. Ovarian reserve testing: a user’s guide. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 217 (2), 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.027 (2017). [published Online First: 2017/02/27].

Technology, S. A. R. SART National Summary Report 2018 (SART National Summary Report, 2017).

Hosseinzadeh, P., Wild, R. A. & Hansen, K. R. Diminished ovarian reserve: risk for preeclampsia in in vitro fertilization pregnancies. Fertil. Steril. 119 (5), 802–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2023.03.002 (2023). [published Online First: 2023/03/11].

Richardson, M. C. et al. Environmental and developmental origins of ovarian reserve. Hum. Reprod. Update. 20 (3), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt057 (2014). [published Online First: 2013/11/30].

Tal, R. & Seifer, D. B. Potential mechanisms for racial and ethnic differences in antimullerian hormone and ovarian reserve. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2013, 818912. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/818912 (2013). [published Online First: 2013/12/19].

Reproductive Endocrinology & Fertility Preservation Section of Chinese Society on Fertility Preservation under Chinese Preventive Medicine Associa- tion. Expert Group of Consensus on Clinical Diagnosis & Management of diminished Ovarian Reserve[J]. J. Reprod. Med. 31 (04), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-3845.2022.04.001 (2022).

Buysse, D. J. et al. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28 (2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 (1989). [published Online First: 1989/05/01].

Buysse, D. J. et al. Relationships between the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and clinical/polysomnographic measures in a community sample. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 4 (6), 563–571 (2008). [published Online First: 2008/12/30].

Chung, F., Abdullah, H. R., Liao, P. & STOP-Bang Questionnaire A practical Approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 149 (3), 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.15-0903 (2016). [published Online First: 2015/09/18].

Johns, M. W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 14 (6), 540–545. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/14.6.540 (1991). [published Online First: 1991/12/01].

Attali, E. & Yogev, Y. The impact of advanced maternal age on pregnancy outcome. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 70, 2–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2020.06.006 (2021). [published Online First: 2020/08/11].

Levi, A. J. et al. Reproductive outcome in patients with diminished ovarian reserve. Fertil. Steril. 76 (4), 666–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02017-9 (2001). [published Online First: 2001/10/10].

Devine, K. et al. Diminished ovarian reserve in the United States assisted reproductive technology population: diagnostic trends among 181,536 cycles from the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology Clinic outcomes Reporting System. Fertil. Steril. 104 (3), 612–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.05.017 (2015). e3.

Oudendijk, J. F. et al. The poor responder in IVF: is the prognosis always poor? A systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update. 18 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmr037 (2012). [published Online First: 2011/10/12].

Nikolaou, D. & Templeton, A. Early ovarian ageing: a hypothesis. Detection and clinical relevance. Hum. Reprod. 18 (6), 1137–1139. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deg245 (2003). [published Online First: 2003/05/30].

May-Panloup, P. et al. Ovarian ageing: the role of mitochondria in oocytes and follicles. Hum. Reprod. Update. 22 (6), 725–743. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmw028 (2016). [published Online First: 2016/08/27].

Kloss, J. D. et al. Sleep, sleep disturbance, and fertility in women. Sleep. Med. Rev. 22, 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.10.005 (2015). [published Online First: 2014/12/03].

Kim, T. et al. Associations of mental health and sleep duration with menstrual cycle irregularity: a population-based study. Arch. Womens Ment Health. 21 (6), 619–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0872-8 (2018). [published Online First: 2018/06/18].

Chen, H. G. et al. Sleep duration and quality in relation to semen quality in healthy men screened as potential sperm donors. Environ. Int. 135, 105368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105368 (2020). [published Online First: 2019/12/13].

Wise, L. A. et al. Male sleep duration and fecundability in a north American preconception cohort study. Fertil. Steril. 109 (3), 453–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.11.037 (2018). [published Online First: 2018/03/24].

Goldstein, C. A. et al. Sleep in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a pilot study. Sleep. Med. 32, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2016.12.007 (2017). [published Online First: 2017/04/04].

Gong, M. et al. The impact of chronic insomnia disorder on menstruation and ovarian reserve in childbearing-age women: a cross-sectional study. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 51 (2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.5653/cerm.2023.06513 (2024). [published Online First: 2024/05/30].

Guyon, A. et al. Adverse effects of two nights of sleep restriction on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in healthy men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99 (8), 2861–2868. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2013-4254 (2014). [published Online First: 2014/05/16].

Balbo, M., Leproult, R. & Van Cauter, E. Impact of sleep and its disturbances on hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 759234. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/759234 (2010). [published Online First: 2010/07/16].

da Costa, C. S. et al. Subacute cadmium exposure disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, leading to polycystic ovarian syndrome and premature ovarian failure features in female rats. Environ. Pollut. 269, 116154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116154 (2021). [published Online First: 2020/12/08].

Straub, R. H. et al. Inflammation is an important covariate for the crosstalk of Sleep and the HPA Axis in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Neuroimmunomodulation. 24 (1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000475714 (2017). [published Online First: 2017/05/24].

Zhu, Z., Xu, W. & Liu, L. Ovarian aging: mechanisms and intervention strategies. Med Rev () 2022;2(6):590–610. doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1515/mr-2022-0031 [published Online First: 2023/09/19].

Kinkead, R. et al. Stress and loss of ovarian function: Novel insights into the origins of Sex-based differences in the manifestations of Respiratory Control disorders during Sleep. Clin. Chest Med. 42 (3), 391–405 (2021). [published Online First: 2021/08/07].

Aiken, C. E. et al. Chronic gestational hypoxia accelerates ovarian aging and lowers ovarian reserve in next-generation adult rats. FASEB J. 33 (6), 7758–7766. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201802772R (2019). [published Online First: 2019/03/20].

Sang, D. et al. Prolonged sleep deprivation induces a cytokine-storm-like syndrome in mammals. Cell. 186(25):5500-16 e21. doi: (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.10.025 [published Online First: 2023/11/29].

Li, Y. et al. Intermittent hypoxia induces hepatic senescence through promoting oxidative stress in a mouse model. Sleep. Breath. 28 (1), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11325-023-02878-1 (2024). [published Online First: 2023/07/16].

Wang, L. et al. Oxidative stress in oocyte aging and female reproduction. J. Cell. Physiol. 236 (12), 7966–7983. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.30468 (2021). [published Online First: 2021/06/15].

Yan, F. et al. The role of oxidative stress in ovarian aging: a review. J. Ovarian Res. 15 (1), 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-022-01032-x (2022). [published Online First: 2022/09/02].

Sun, Z. M. et al. Resveratrol protects against CIH-induced myocardial injury by targeting Nrf2 and blocking NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Life Sci. 245, 117362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117362 (2020). [published Online First: 2020/01/31].

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xue-Fen Cai, study design and preparation of the manuscript; Bi-Ying Wang, study design; Jian-Ming Zhao, analyzed data; Mei-Xin Nian, collected data; Qi-Chang Lin, study design; Jie-Feng Huang, sequence/data analysis and preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cai, XF., Wang, BY., Zhao, JM. et al. Association of sleep disturbances with diminished ovarian reserve in women undergoing infertility treatment. Sci Rep 14, 26279 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78123-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78123-w