Abstract

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which are immutable and transferable tokens on blockchain networks, have been used to certify the ownership of digital images often grouped in collections. Depending on individual interests, wallets explore and purchase NFTs in one or more image collections. Among many potential factors of shaping purchase trajectories, this paper specifically examines how visual similarities between collections affect wallets’ explorations. Our model characterizes each wallet’s explorations with a Lévy flight and shows that wallets tend to favor collections having similar visual features to their previous purchases while their behaviors vary widely. The model also predicts the extent to which the next collection is close to the most recent collection of purchases with respect to visual features. These results are expected to enhance and support recommendation systems for the NFT market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are immutable and traceable objects on blockchain networks so that can be used to prove the ownership of digital assets, including artwork, photo, audio, and video. Nowadays, most NFTs are in collections sharing similar concepts and traits, such as hat, glass, and background color. For example, a famous collection ‘Bored Ape Yacht Club’ is made of NFTs of cartoon apes. Artists creating collections sell NFTs to wallets, and these wallets sell NFTs to other wallets through marketplaces referred to as the NFT market in this paper.

The prices of NFTs are associated with visual features (e.g., pixel, color)1,2. The extent to which traits and their combinations are rare affects NFTs’ market values3. New NFT collections inspired by the visual design of existing collections tend to have similar financial performance to the existing collections4. Considering that the price of an NFT is determined by its demand, visual features may also influence demand and individual wallet’s purchase decisions, specifically whether to purchase NFTs having similar or different visual features.

Wallets face diverse options at the moments of purchase. The uncertainty of choices leads different purchase trajectories by wallet. Some wallets possess only one NFT collection, while others purchase various collections. These two cases can be mapped to ‘Exploitation’ and ‘Exploration’, respectively, where exploitation is a behavior maximizing the current utility by re-using known options and exploration is a behavior taking risk for higher returns by searching uncertain environments5,6.

Decisions whether to choose exploration or exploitation are made based on environmental, social, individual factors7. The belief constructed from the previous environment does not hold in the new environment and in turn would change the decisions8. Competition is another environmental factor. If competitions exist, the risk of exploration increases because there is a possibility that competitors already exploited the environment. Under competition, expected returns would decrease and lead to a tendency leaning toward exploitation9. The risk of exploration can decrease if social information is available in decision-making10. If a person identifies the major decision in a system through social information, this person is more likely to follow the major decision11. It is because of network effects that increasing population which chooses the major decision is expected to receive higher returns compared to others choosing non-major decisions. Prior experience also affects decisions in the future. When customers of an online food delivery service explore new cuisines, they tend to choose cuisines similar to the foods they ordered12.

Environmental and social factors are surely important in the NFT market, but they are difficult to measure as the NFT market has evolved fast and does not reveal personal identities and their connections. Therefore in this paper, we focus on individual wallets and analyze how they exploit an NFT collection and explore new collections based on a visual similarity. We set the research questions as:

-

RQ1:

How do exploration and exploitation occur in the NFT market?

-

RQ2:

Do wallets explore new NFTs in collections having visual features similar to their previous collections of purchases?

Researchers found that behavioral trajectories in nature and social systems consist of many short movements and a few long jumps to distant areas with low probabilities. Honey bees13, desert ants14, sharks15, deers16, and elephants17 search resources by following this pattern. Humans are not an exception. They make long non-local jumps occasionally in physical spaces18,19,20 and virtual spaces21.

Lévy flight22 is a random walk model explaining this pattern with a probability distribution \(d^{-\alpha }\) where d is a distance between two points in a trajectory and \(\alpha\) is a positive value between 1 and 3 in many real-world systems21,23. This distribution generates frequent short movements and rare long jumps because of its fat tail. Borrowing the functional form of Lévy flight, we aim to examine whether wallets explore the NFT market with the same pattern. In other words, if estimated \(\alpha\) values for wallets are between 1 and 3, we would argue that wallet owners’ behave similarly with agents in many real-world systems. To analyze visual similarities between NFT collections, we projected NFTs to an embedding space by using ResNet1824, a deep neural network specialized for image classification task, and used (1 − the cosine similarity between two embedding vectors) as d (see “Methods” for details).

-

RQ3:

Do wallets explore NFT collections similarly to agents in physical systems with the pattern of frequent short but rare long movements?

Models

Wallets would have distinct purchase trajectories depending on their owners’ preferences and personal characteristics. We developed three models generating synthetic purchase trajectories and compared them with the data to explain potential factors shaping the real purchase trajectories (Fig. 1). The following notations are used for explaining our models. Each wallet has a trajectory T, which is a sequence of collections of NFTs that its owner purchased. \(T_{i}\) is the trajectory of a wallet i, and \(t_{i,j}\) is the jth collection in \(T_{i}\). Trajectories have different length and starting collection, so for a wallet i, we fix both \(|T_{i}|\) and \(t_{i,1}\) in simulations to compare synthetic trajectories with the data fairly. Details for constructing purchase trajectories are provided in Methods.

A schematic diagram of the models. The figure of NFTs are from ‘NotOkayBears’. Tables in the figure show probabilities that a collection is chosen as the next collection. Model 1 (M1) selects the next collection randomly. This model is the baseline for comparison with other models. Model 2 (M2) introduces an exploration parameter p, which decides the frequency of exploration. In this model, an agent explores a new collection with a probability p. In case of exploration, the next collection is selected randomly. Model 3 (M3) is similar to Model 2 but the next collection is sampled from a function following Lévy flight with an exponent \(\alpha\).

Model 1

The first model is a completely random model. For each wallet, after fixing the starting collection, we sampled collections randomly from the list of all collections C with equal probabilities. The probability that a collection is chosen as the next collection is 1/|C|. This model is simple but allows us to understand the NFT collection embedding space with the step length distribution, a distribution for jump distances within trajectories. For example, if a wallet has a sequence \([C_1, C_1, C_2, C_3]\), then a set of step lengths for this sequence becomes \(\{d(C_1, C_1), d(C_1, C_2), d(C_2, C_3)\}\) where d(X, Y) is the cosine distance between the collection embedding vectors of X and Y. Note that d(X, X) is zero. Since this model generates random sequences, the aggregated step length distribution from all wallets \(f_{null}(d)\) represents probabilities to sample collections reachable at a distance d (Fig. 2). This distribution is not biased by other external factors and represents the inherent topology of the embedding space.

Model 2

However, wallet owners’ would not purchase NFTs randomly. They are likely to have different preferences on exploring and exploiting collections. To measure the preferences, for a wallet i, we calculated \(p_i\) which is the proportion of choosing a different collection from the most recent purchase. For example, a wallet i of which purchase trajectory is \(\{C_1, C_1, C_2, C_3\}\) changes collections twice, \(C_1 \rightarrow C_2\) and \(C_2 \rightarrow C_3\), while the total number of changes is three. Then, \(p_i\) becomes 2/3. We assume that \(p_i\) estimated from the data represents i’s unique characteristics so fix the values in modeling.

The second model adds the effect of \(p_i\) to the first model. It generates a sequence as follows. A wallet owner i decides whether to buy an NFT in the same collection of the previous purchase or not. i explores a new collection with a probability \(p_i\) or exploits the collection of the most recent purchase with a probability \(1-p_i\). In case of exploration, a collection is randomly chosen as the next collection with a probability \(1/(|C|-1)\). Comparing the first and the second models, we can better understand the impact of \(p_i\).

Model 3

Lastly, we incorporated personal characteristics about selecting a new collection. Some wallet owners tend to choose a collection similar to the previous collection, while others tend to choose a collection different from the previous collection. We adopt a Lévy flight function to implement this mechanism because Lévy flights explain exploration behaviors well in many social systems25,26.

In the third model, the next collection is chosen with a probability proportional to \(1/d^{\alpha _{i}}\), where d is the cosine distance between two collections’ embedding vectors and \(\alpha _i\) represents wallet i’s preference of choosing collections similar to the previous collection. If \(\alpha\) is positive, a wallet tends to choose similar collections. If \(\alpha\) is negative, a wallet tends to choose collections distant from the most recent collection. We name \(\alpha\) as ‘visual affinity exponent’.

The likelihood of a trajectory \(T_i\) is calculated from a prior distribution for a given \(\alpha\). It is the multiplication of probabilities for distances between collections, based on a prior distribution \(f(d|\alpha )\). In our previous example \(\{d(C_1, C_2), d(C_2, C_3)\}\), its likelihood is \(f(d(C_1, C_2)|\alpha ) \times f(d(C_2, C_3)|\alpha )\) where \(f(d|\alpha )\) is defined as:

\(f_{null}(d)\) and two exemplar \(f(d|\alpha )\) distributions are shown in Fig. 2. The \(f(d|\alpha =2)\) is shifted to the left compared to the null distribution, which means that wallets following this distribution prefer to purchase NFTs in collections similar to the previous collections. Note that \(f_{null}(d)\) is identical to \(f(d|\alpha =0)\).

Two exemplar prior distributions and the null distribution. The null distribution represents the topology of the embedding space. If a wallet randomly selects the next collection for purchase, then the probability to choose a collection follows the null distribution. \(f(d|\alpha =2)\) and \(f(d|\alpha =-2)\) are prior distributions for the maximum likelihood method. If the visual affinity exponent \(\alpha\) of a wallet is positive (blue curve), the wallet prefers to select similar collections. If \(\alpha\) is negative (red curve), a wallet tends to choose different collections compared with the previous one.

For each wallet, we estimate \(\alpha\) maximizing the likelihood of obtaining its purchase trajectory and set it as the wallet’s visual affinity exponent. Unfortunately, we can’t calculate \(\alpha\) values analytically because the collections are already distributed on the embedding space and their distributions are not represented with general functions. To make our estimation feasible, we change values from -6 to 6 with a step size of 0.1 and determine the value of the highest likelihood as \(\alpha _i\) for a wallet i.

Results

Model comparisons

We generated 100 synthetic purchase trajectories for each wallet and compared them with its real purchase trajectory by calculating a distance error DE, which is the normalized average difference between the total distance of the real purchase trajectory and the total distance of a synthetic purchase trajectory. This value for a wallet i is represented as

where \(|T_i|\) is the length of i’s purchase trajectory, j is the order of purchase in the trajectory, s is the index of a synthetic trajectory, and \(C^{s}_{i,j}\) is the jth collection in the sth synthetic trajectory.

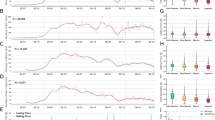

The distributions for distance errors of Model 1 (completely random), Model 2 (explore with a probability p and choose next collections randomly), and Model 3 (explore with a probability p and choose next collections by following a Lévy flight function \(d^{-\alpha }\)). The closer a distribution is to the dashed line (DE=0), the better its associated model performs.

Figure 3 shows how DE values are distributed by model. Model 1, which creates random trajectories, has the highest error. Adding the exploration probability p increases model performance significantly (Model 2). It suggests that exploitation with a probability of \(1-p\) shapes purchase trajectories to a large extent. In addition to p, Model 3 incorporates a Lévy flight function with the visual affinity exponent \(\alpha\), which quantifies the tendency of purchase an NFT in a collection similar to the previous collections. We confirmed that Model 3 performs best with both the exploration probability p and the visual affinity exponent \(\alpha\). In the next section, we examine detailed properties and behaviors of wallets in the NFT market, especially focusing on estimated p and \(\alpha\) values.

Interpreting wallet behaviors with estimated parameters

The distributions for the model parameters p and \(\alpha\). (A) p is the exploration probability, which is equal to the proportion of inter-collection jumps. (B) \(\alpha\) is the visual affinity exponent estimated from a Lévy flight function. High \(\alpha\) means the tendency to choose a similar collection for the next purchase. The distribution in gray shows estimated \(\alpha\) values from 100 random sequences generated by Model 2.

Tendency to explore collections

The estimated p values suggest that there are mainly two groups of wallets (Fig. 4a). The first group consists of wallets exploiting only one collection (\(p=0\)). We would like to reiterate that the wallets which purchased more than 10 NFTs were analyzed, so this peak is not an artifact by low numbers of purchases. The other group comprises wallets exploring at least one collection (\(p>0\)). Estimated p values are broadly distributed in this group. It indicates that the tendency to explore collections varies by wallet but not converges. Interestingly, there are more wallets of which p value is lower than 0.5. The distribution implies that wallets in the NFT market tend to exploit a collection or explore relatively less.

Visual affinity to collections

The visual affinity exponent \(\alpha\) represents the extent to which a wallet favors new collections similar to the previous collections in its purchase trajectory. The distribution for \(\alpha\) from the data is left-skewed (skewness = − 0.6) and has a single peak at 0.7 with the median of 0.4 (Fig. 4b; The distribution colored in gray green). This pattern cannot be generated from random sequences. \(\alpha\) values estimated from random sequences by Model 2 are distributed around 0 (Fig. 4b; The distribution colored in blue). The distribution implies that the NFT market consists of wallets having diverse preferences, but there are more wallets favoring collections similar to previous purchases (positive \(\alpha\)) compared to others exploring dissimilar collections (negative \(\alpha\)). On average, wallets behave in a conservative way in exploring collections while no physical risk and constraints exist in the embedding space.

Application for a recommendation system

We built a simple recommendation model predicting the last collection of a purchase trajectory with p and \(\alpha\) estimated from the collections in the trajectory except the last collection. For example, in a trajectory \([C_1, C_1, C_2, C_3]\), we exclude the last collection \(C_3\) and estimate p and \(\alpha\) from \([C_1, C_1, C_2]\). We sampled the collection after \(C_2\) 10 times (\(X_1, \ldots , X_{10}\)) from Model 3, calculated \(d(C_2, X_1),\ldots , d(C_2, X_{10})\), and compared the average distance of \(d(C_2, X_1),\ldots , d(C_2, X_{10})\) with the true value \(d(C_2, C_3)\). Figure 5 shows test results for the wallets of which last and second-to-last collections are different. Model 3 performs better than a null model that randomly predicting a collection even for the wallets having same last and second-to-last collections (SI Section 4). The average distances from predictions are highly similar to the actual data, resulting in the trend close to \(y=x\) (Fig. 5). This result supports that p and \(\alpha\) are effective parameters describing wallet behaviors and can be used to build recommendation systems for NFT collections.

Discussion

Our results confirm that the exploration probability p and the visual affinity exponent \(\alpha\) characterize wallets’ behaviors in selecting NFT collections well. The estimated parameters answer our research questions as below.

For the first research question about how exploitation and exploration occur in the NFT market, we examined estimated p values from the data. At the NFT collection level, exploitation and exploration correspond to the cases of \(p=0\) and \(p>0\), respectively. The proportion of exploitation is 10%, which is not neglectable but indicates exploration is more popular in the NFT market. The broad p distribution also shows that the extent of exploration varies by wallet (Fig. 4a).

Our second research question is whether visual similarity affects exploration across NFT collections. We observed a large portion of the non-zero \(\alpha\) values. It suggests visual similarity does matter in making exploration decisions (Fig. 4b). Specifically, as the mode and median of the \(\alpha\) distribution are positive, we argue that wallets prefer similar collections when exploring the NFT market overall.

The \(\alpha\) distribution answers our third research question “Do wallets in the NFT market explore similarly with agents in real-world physical systems?”. Literature about Lévy flight reports that the exponent is between 1 and 3 in many physical systems27. Our result shows that there are indeed many wallets in this range but interestingly more wallets have an exponent below 1. Low exponents lead wallets to explore even less similar or dissimilar collections in the embedding space.

This difference may be understood with the structure and characteristics of spaces and agents. Physical systems have limited reachable areas from a point, while our embedding space does not. Wallet owners can obtain any information about collections. Some wallets purchasing NFTs in collections distant in the embedding space can have negative \(\alpha\). In addition, wallet owners may have diverse motivations in the NFT market. Some owners purchased NFTs for investment, while others did it for artistic collection purpose28. In the latter case, wallets having a preference to specific visual components would show positive \(\alpha\) values while the degree of the preference varies.

In summary, our model effectively captures the individual behaviors of wallets through the visual affinity exponent \(\alpha\), which characterizes the level that each wallet favors collections visually similar with its previous purchases. The key strength of our approach is to directly compute exploration parameters for individuals from empirical data and to construct the distribution of exploration patterns with the estimated parameters.

Our approach is not without limitations. First, it assumes that a wallet’s next decision is affected solely by its most recent purchase, identical to a Markov process. This assumption prevents us from accounting for long-range correlations in a purchase sequence. Second, the model does not consider other plausible factors, such as the popularity of a collection and its creator, the launch date of a collection, and NFT’s price, so its explanatory power is not substantially high. Lastly, exploration behaviors may vary over time and by market events. For instance, the release of a popular collection could change exploration behaviors (SI Section 5). Therefore, our results primarily reflect the current decision-making processes of individual wallets.

Advanced models addressing these limitations will enhance our understanding of exploration and exploitation behaviors in the NFT market. Especially, considering NFT promotion activities on social media29, analyzing the impact of social networking services on exploration behaviors in the NFT market would be an interesting topic for future studies. Our contribution showing the importance of visual features in the NFT market can also be extended further to examine whether specific visual components (e.g., patterns, colors) are more influential than others in NFT purchase decisions.

Methods

NFT transfer data

It is challenging to identify individual buyers for many physical artworks. For example, Picasso’s La Dormeuse was sold for 57.8 million US dollars, but we don’t know who owns it30. In contrast, the NFT market is governed by smart contracts which record transactions in blockchain networks, so we can examine when a new NFT was minted to a wallet and which wallets purchased NFTs. Details of transactions such as fees and asset values are also available on blockchain networks. This property allows us to reconstruct each wallet’s purchase trajectory while maintaining individual privacy, since each wallet address is a hashed string that cannot be connected to real-world personal identities.

A schematic diagram of data collection and cleaning. First, we selected 198 NFT collections and gathered transfer data from the Ethereum ETL project in Google BigQuery. After collecting transfer data, we grouped rows by buyer (‘To’ columns in the table) and transformed them into purchase trajectories at the NFT level. Then, the purchase trajectories at the NFT level is converted to the trajectories at the collection level after removing duplicated NFT purchases.

We specifically focused on the top 1000 NFT collections with respect to volume in the Etherium network, according to the OpenSea ranking statistics on June 27, 2024. We estimated that these collections would cover 78% of the total volume. Detailed information about data processing, estimation, and validation can be found in SI Section 1. We excluded some NFT collections based on the following criteria (Fig. 6 - Step 1). First, we removed collections that consist of nearly identical images. For instance, ‘Opepen Edition’, ‘Checks—VV Edition’, and ‘Damien Hirst—The Currency’ that have simple features, such as random dots with only color variations, were excluded. Second, we removed NFT collections that have factors beyond image itself. For example, NFT collections about soccer players incorporate players’ game performance in price so that were excluded not to confound our analysis. These steps yield a list of 598 NFT collections (See SI for the full list of NFT collections used in this paper)

Two different token standards—ERC-20 and ERC-721—are used for the selected collections. ERC-20 generates a new currency unit with its own standards in the network. Tokens associated with a system built on ERC-20 are interchangeable. In an ERC-20 system, 10 tokens of a wallet are worth as same as 10 tokens of another wallet. However, a token in an ERC-20 system can’t be traded with a token in another ERC-20 system. Regarding our research, CryptoPunk is the only collection using ERC-20. Each digital artwork in CryptoPunk acts as an independent currency unit with a maximum supply of 1. This characteristic makes artworks not replicated and not interchangeable as they are different ERC-20 tokens. On the other hand, tokens with ERC-721 are not fungible and exist uniquely. Therefore, they represent the ownership of digital artworks. Most NFT collections are hosted with the ERC-721 standard.

We leveraged the Ethereum ETL project built upon Google BigQuery31 to collect NFT transactions associated with ERC-20 and ERC-721 (Fig. 6 - Step 2). The raw data were then refined further to have direct transfers between individual wallets. This dataset includes information about sellers (from) and buyers (to) with timestamps for NFT transfers (Fig. 6 - Step 3). From this dataset, we generated every individual’s purchase trajectory by grouping transfers by buyer in the ascending order of time (Fig. 6 - Step 4).

Constructing purchase trajectories

The main goal of this paper is to understand exploring behaviors in the NFT market, so we focused on unique NFTs in purchase trajectories (Fig. 6 - Step 5). For example, the trajectory of Wallet 2 (W2) in Fig. 6 is [N1, N1], which means a re-purchase of N1, and we reduced the trajectory to [N1]. We also converted trajectories at the NFT level to those at the collection level (Fig. 6 - Step 5). The trajectory of Wallet 3 (W3) in Fig. 6 becomes [C1, C1, C2]. In our study, [C1, C1] is an intra-collection jump corresponding exploitation and [C1, C2] is an inter-collection jump corresponding exploration.

Finally, we filtered out wallets of which collection-level trajectory having less than 5 or more than 1000 transactions. It is because that the trajectories having less than 5 transactions are not good enough for analysis and the trajectories having more than 1000 transactions are more likely to be made by bots, contract accounts, and marketplaces, which are beyond our scope. 539,542 distinct wallets remain for further analyses (see a detailed validation of this limit range in SI Section 1).

NFT and collection embeddings

Image embedding is a technique projecting an image to a low-dimensional vector while preserving its features with a little loss. Similar images are positioned close on a vector space. We collected NFT images through the links provided by the OpenSea API and used a pre-trained ResNet1824, a deep neural network specialized for image classification task, to calculate NFT embeddings in 512 dimensions. We evaluated and confirmed the robustness of our result with the VGG16 embedding method32 (SI Section 3).

NFT embeddings allow us to characterize collections as well. We obtained the centroid of NFT embeddings of a collection and define it as collection embedding. An advantage of having collection embeddings is that we are able to quantify similarities between collections. In this paper, we used the cosine similarity between collection embeddings as a similarity measure. Using Euclidean distances on the embedding space yielded consistent results (SI Section 2). Suppose a wallet purchased an NFT in Collection A and then another in Collection B. This wallet’s purchasing history can be described as a jump from A’s embedding to B’s embedding. If these collections are similar with respect to visual features, the jump distance from A to B is relatively short. However, if this wallet purchased an NFT in Collection C, which is significantly different from A and B, the jump distance from B to C is longer than the distance from A to B.

We validated the embedding space by randomly choosing three collections and comparing each collection with its five closest collections with respect to the cosine distance (1-cosine similarity; Table 1). ‘3Landers’ has pastel colors, and its NFTs have a round cartoon design. ‘Dippies’ is the most closest collection on the NFT embedding space to ‘3Landers’ and shares similar colors and a round cartoon design. ‘Chain Runners’ is composed with pixel arts, and its five closest collections have similar pixel designs. The closest neighbor of the final example ‘NotOkayBears’ is ‘Okay Bears Yacht Club’. As the collection name implies, they are similar in many aspects, including character design. Other collections close to ‘NotOkayBears’ on the embedding space also share a similar design with a famous NFT collection ‘Bored Ape Yacht Club’4. These observations validate our NFT embedding space.

Data availibility

The data used in this manuscript is open source, and the sources are referenced in the manuscript. Codes will be available upon request to the corresponding author, Hyunuk Kim.

References

Nadini, M. et al. Mapping the NFT revolution: market trends, trade networks, and visual features. Sci. Rep. 11, 20902. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00053-8 (2021).

Fridgen, G., Kräussl, R., Papageorgiou, O. & Tugnetti, A. Pricing dynamics and herding behavior of NFTs. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4337173 (2023) (Preprint).

Mekacher, A. et al. Heterogeneous rarity patterns drive price dynamics in NFT collections. Sci. Rep. 12, 13890. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17922-5 (2022).

La Cava, L., Costa, D. & Tagarelli, A. Visually wired NFTs: Exploring the role of inspiration in non-fungible tokens, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.17031 (2023). arXiv: 2303.17031 [physics].

March, J. G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 2, 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.71 (1991).

Cohen, J. D., McClure, S. M. & Yu, A. J. Should i stay or should i go? How the human brain manages the trade-off between exploitation and exploration. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 362, 933–942 (2007).

Mehlhorn, K. et al. Unpacking the exploration–exploitation tradeoff: A synthesis of human and animal literatures. Decision 2, 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/dec0000033 (2015).

Posen, H. E. & Levinthal, D. A. Chasing a moving target: Exploitation and exploration in dynamic environments. Manage. Sci. 58, 587–601. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1420 (2012).

Phillips, N. D., Hertwig, R., Kareev, Y. & Avrahami, J. Rivals in the dark: How competition influences search in decisions under uncertainty. Cognition 133, 104–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.06.006 (2014).

Valone, T. J. Group foraging, public information, and patch estimation. Oikos 56, 357. https://doi.org/10.2307/3565621 (1989).

Lee, J., Lee, J. & Lee, H. Exploration and exploitation in the presence of network externalities. Manag. Sci.[SPACE]https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.49.4.553.14417 (2003).

Schulz, E. et al. Structured, uncertainty-driven exploration in real-world consumer choice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116, 13903–13908. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821028116 (2019).

Reynolds, A. M. et al. Displaced honey bees perform optimal scale-free search flights. Ecology 88, 1955–1961. https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1916.1 (2007).

Reynolds, A. M. Optimal random Lévy-loop searching: New insights into the searching behaviours of central-place foragers. Europhys. Lett. 82, 20001. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/82/20001 (2008).

Sims, D. W., Witt, M. J., Richardson, A. J., Southall, E. J. & Metcalfe, J. D. Encounter success of free-ranging marine predator movements across a dynamic prey landscape. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 273, 1195–1201. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3444 (2006).

Focardi, S., Montanaro, P. & Pecchioli, E. Adaptive Lévy walks in foraging fallow deer. PLoS One 4, e6587. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0006587 (2009).

Dai, X., Shannon, G., Slotow, R., Page, B. & Duffy, K. J. Short-duration daytime movements of a cow herd of African elephants. J. Mammal. 88, 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1644/06-MAMM-A-035R1.1 (2007).

Brockmann, D., Hufnagel, L. & Geisel, T. The scaling laws of human travel. Nature 439, 462–465. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04292 (2006).

Brown, C. T., Liebovitch, L. S. & Glendon, R. Lévy flights in Dobe Ju/’hoansi foraging patterns. Hum. Ecol. 35, 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-006-9083-4 (2007).

González, M. C., Hidalgo, C. A. & Barabási, A.-L. Understanding individual human mobility patterns. Nature 453, 779–782. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06958 (2008).

Garg, K. & Kello, C. T. Efficient Lévy walks in virtual human foraging. Sci. Rep. 11, 5242. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84542-w (2021).

Mandelbrot, B. B. & Mandelbrot, B. B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature Vol. 1 (WH freeman, New York, 1982).

Zaburdaev, V., Denisov, S. & Klafter, J. L\’evy walks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 483–530. https://doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.87.483 (2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Riascos, A. P. & Mateos, J. L. Random walks on weighted networks: a survey of local and non-local dynamics. J. Complex Netw. 9, cnab032. https://doi.org/10.1093/comnet/cnab032 (2021).

Humphries, N. E. & Sims, D. W. Optimal foraging strategies: Lévy walks balance searching and patch exploitation under a very broad range of conditions. J. Theor. Biol. 358, 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2014.05.032 (2014).

Viswanathan, G. M., Da Luz, M. G., Raposo, E. P. & Stanley, H. E. The Physics of Foraging: An Introduction to Random Searches and Biological Encounters (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Yilmaz, T., Sagfossen, S. & Velasco, C. What makes NFTs valuable to consumers? Perceived value drivers associated with NFTs liking, purchasing, and holding. J. Bus. Res. 165, 114056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114056 (2023).

Kapoor, A. et al. TweetBoost: Influence of Social Media on NFT Valuation. In Companion Proceedings of the Web Conference 2022, WWW ’22, 621–629, https://doi.org/10.1145/3487553.3524642 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2022).

Phillips Steps It Up With a Triumphant \$135 Million Auction in London, the House’s Best Ever (2018). (accessed 15 Jan 2024).

Blockchain ETL. blockchain-etl/ethereum-etl: Python scripts for ETL (extract, transform and load) jobs for Ethereum blocks, transactions, ERC20/ERC721 tokens, transfers, receipts, logs, contracts, internal transactions. Data is available in Google BigQuery https://goo.gl/oY5BCQ (2019) (accessed 15 Jan 2024).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556 (2015). ArXiv:1409.1556 [cs].

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government. (MSIT) (RS-2024-00360920). This work was partly supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No.RS-2019-II191906, Artificial Intelligence Graduate School Program (POSTECH)) and Korea Evaluation Institute of Industrial Technology (KEIT) grant funded by the Korea government (MOTIE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to designing the study, writing and revising the manuscript. S.J. collected the data, S.J. and H.K. developed the models and visualized outcomes.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jo, S., Jung, WS. & Kim, H. Wallets’ explorations across non-fungible token collections. Sci Rep 14, 28335 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78379-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78379-2