Abstract

Microplastics (MPs) in subsurface environments are migratory and can carry heavy metals, increasing the extent of MP and heavy metal pollution. This study used quartz sand-filled column experiments to investigate the adsorption and cotransport behaviours of PS-MPs, O3, UV-aged PS-MPs, and Cu2+ at different MP concentrations, ionic strengths, and ionic valences in a saturated porous medium. The results showed that when MPs migrate alone in the absence of an ionic background, higher concentrations have increased mobility. In contrast, an increase in the background ion concentration or ion valence inhibits the individual transport capacity of PS-MPs. An increase in the concentration of background ions or elevation in the valence state promotes Cu2+ transport because of the action of the double electric layer on the surface of the colloid and the electrostatic repulsive forces combined with the background ions. The adsorption capacity of aged PS-MPs was stronger than that of PS-MPs because of the binding of the aged PS-MPs to Cu2+ through complexation and electrostatic attraction. In the binary system of PS-MPs/Cu2+, PS-MPs promoted Cu2+ transport and the mobility of Cu2+ loaded by PS-MPs decreased with increasing background ion concentration. The cotransport results showed that MPs promote Cu2+ transport in the following order: O3-aged Ps > UV-aged Ps > Ps, as the increasing cation concentration in the MPs and Cu2+ occupies the PS surface adsorption sites. Overall, PS is an effective carrier for Cu2+. These findings offer fresh exploration concepts for the joint migration of MPs and heavy metals in underground settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plastic products are widely used in large quantities in industry, agriculture, and daily life, bringing great convenience to people; however, large amounts of plastics are discarded and difficult to recycle, resulting in serious environmental pollution1. Furthermore, plastic waste is broken down by the natural environment and other physical, chemical, and biological processes into smaller plastic fragments or particles, of which microplastics (MPs) have a particle size of < 5 mm2. MP pollution has turned into a global environmental problem. Over the last 50 years, plastic debris has been found in habitats, soil, water, and air across the globe3. This has serious impacts on ecosystems and human health4. In addition, agriculture, construction, Leakage of waste leachate, and sewage sludge treatment and purification can lead to its extensive dispersal in the subsurface environment5,6. Prolonged contact with MPs present in the soil elevates the potential hazards to groundwater and other water bodies7.

For the past few years, the referred to as “Trojan Horse” influence of MPs has attracted considerable attention8,9,10. Traditional wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) and drinking water treatment plants (DWTP) are unable to completely remove microplastics (MPs) from water/wastewater11. Owing to the distinct properties of MPs (e.g. large specific surface area, high adsorption capacity, and functional groups on the surface), they have the potential to serve as transporters of contaminants (e.g., organic contaminants, heavy metals, and antibiotics) to facilitate contaminant transport and provide additional exposure pathways for contaminants to the environment and organisms1. Due to their strong adsorption capacity, MPs can adsorb and transport metal and organic pollutants during migration, and desorb them elsewhere, facilitating their transport. Additionally, the desorption behavior of pollutants from MPs and natural media plays a crucial role in environmental risk assessment12,13. Research has revealed that MPs exhibit toxicity towards numerous organisms14,15,16, and they may pose a greater environmental risk as pollutant carriers. In saturated porous media, contaminants loaded onto MPs have the capability to travel vast distances, thereby influencing their dispersal within the subsurface environment and expanding the spatial transport of contaminant elements. When MPs coexist with metal ions in aquatic environments, they can serve as carriers for transporting and migrating these ions. Zhou et al.17 investigated the adsorption mechanism of Cd(II) on five types of MPs and found that oxygen-containing functional groups predominantly governed the adsorption process. Guan et al.18 demonstrated that the primary adsorption mechanism of Sr2 + on three types of MPs is electrostatic interaction. The adsorption process also affects the persistence and mobility of MPs in the environment. Adsorbed pollutants can change the density of MPs, affecting their settling and suspension behavior in water bodies19. Additionally, adsorption changes the chemical properties of MP surfaces, further influencing their migration and distribution in various environmental media20. In addition, the cotransport behaviour relies on the composition and structure of the colloidal particles, surface properties, and physicochemical parameters of the surrounding environment (e.g., temperature, concentration, and pH)21,22.

MPs in the natural environment (e.g., solar radiation and ocean waves) inevitably age. Ageing significantly affects the physicochemical properties of plastics by functional groups, altering particle size, specific surface area, and surface potential23,24. Thus, compared with pristine MPs, ageing and exposure to ultraviolet light irradiation (UV) or ozone (O3) may affect their fate, transportation, and environmental impact. Furthermore, ageing might considerably boost the migration of spherical polystyrene (PS) nanoplastics in saturated loamy sands and their ability to synergistically migrate in conjunction with nonpolar and polar pollutants25. Polymer properties and environmental characteristics affect the degradation rate of MPs26. The unsaturated chemical bonds in these polymers are prone to breaking and forming new bonds during the ageing process, thus increasing the number of functional groups in MPs. This gives rise to increased adsorption of some pollutants by ageing MPs, resulting in more serious environmental pollution23,27. As a result, further research on the synergistic transport behaviour of MPs under different physicochemical conditions is required to elucidate their environmental risks.

Previous studies emphasized on adsorption behaviour of MPs for organic contaminants because of the non-degradable properties of heavy metals and severity of pollution in the underground environment caused by the migration, transformation, and accumulation of heavy metals28,29. Heavy metals can accumulate in several types of MPs12. MPs also have a high adsorption ability for some heavy metals and organic contaminants in the environment, increasing the bioavailability of heavy metals and affecting the material cycle30,31. In aquatic environments, Pb2+ and Cd2+ are among the top five toxic elements, whereas Cu2+ ions are considered priority pollutants32, and metal ions coexist with MPs in aqueous environments33,34. Since Cu2+ and MPs may coexist in the same system35, studying copper’s behavior and effects under various environmental conditions is crucial for understanding heavy metal pollution and its ecological risks36. Because there are few studies on the mechanism of interaction and synergistic transport behaviour of MPs and heavy metals in natural environment with different MP concentrations and ionic strengths (IS), it is essential to address the transport of MPs and heavy metals within the environment.

PS with a particle size of 80 nm is a common polymer widely present and used in many consumer products. It can be directly released into the environment from these products and is frequently found in the environment, making it a significant source of microplastic pollution37,38. Similarly, Copper is a metal with excellent electrical and thermal conductivity, widely used in the electrical, electronic, and construction sectors. Copper is chosen primarily for its environmental stability and bioavailability. As an essential trace element, copper has vital physiological functions in organisms; however, excessive amounts can lead to toxicity. Its potential for environmental pollution poses significant risks to both ecosystems and human health39. Consequently, PS was selected as the test MP using an in-house simulation test. Filled-column saturated percolation simulation experiments were conducted for PS MPs under different conditions to investigate the interactions between aged PS, PS, and Cu2+ in saturated porous media. Ageing PS was obtained by oxidation with UV and O3. The purpose of this investigation was to fully understand the individual and synergistic transport behaviours of PS, aged PS, and Cu2+ in porous media with diverse ionic valences and concentrations. The Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek (DLVO) theory was employed to reveal the interactions of PS + Cu2+, aged PS + Cu2+, and quartz sand in the binary transport system. PS and aged PS were compared under different physicochemical parameters (ageing conditions, IS, and coexisting cations) to identify differences in cotransport with Cu2+. We aim to elucidate the interaction mechanisms and environmental impact pathways of polystyrene (PS) and Cu²⁺ under various solution conditions through simulated experiments. Our research aims to fill existing knowledge gaps by providing detailed insights into the synergistic or antagonistic behaviors of these substances. This study identifies the need for the prevention and control of synergistic contamination by MPs and heavy metals and provides an integrated assessment of their fate and ecological risks in groundwater aquifer systems.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

PS microspheres with a particle size of 80 nm were used in the PS suspension experiments (Tianjin Besler Chromatography Technology Development Center). The microsphere concentration was first diluted to 250 mg/L, after which 250 mL of the diluted solution was removed and placed into an ultrasonic cleaner (KQ2200E, Kunshan Ultrasonic Instruments, China) for 35 min to ensure that the microspheres were uniformly dispersed. For UV ageing, samples containing microspheres were subjected to a mercury lamp (500 W) at 20℃ for 12 h with continuous stirring40. A UV-aged MP stock solution (UV-PS) was obtained at a concentration of 250 mg/L by simulating the exposure of MPs to UV light in a natural environment. O3 ageing was conducted by passing O3 into 500 mL of a diluted PS microsphere suspension at a rate of 0.1 g/min for 9 h with continuous stirring. By simulating the O3 oxidation to which MPs may be subjected in the natural environment, a stock solution of O3-aged MPs at a concentration of 250 mg/L, referred to as O3-PS, was obtained. Studies have shown that Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations in natural aquatic environments are generally < 1000 mmol/L41; therefore, 1, 5, and 10 mmol/L NaCl and CaCl2 concentrations were used for the IS background electrolyte solutions to dilute the PS-MP suspensions to 10, 20, and 30 mg/L, respectively, where Cu(NO3)2, NaCl, and CaCl2 were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. The initial pH of the suspension was regulated to 4.2 ± 0.2 using 100 mmol/L NaOH and HCl to avoid the precipitation of Cu2+ ions.

Quartz sand pretreatment

Quartz sand (Sigma-Aldich) with a particle size of 50–70 meshes was used. Deionised water was used to clean the quartz sand until there were no obvious impurity particles in the upper suspension. The cleaned quartz sand was then placed in a 1% hydrochloric acid immersion for 24 h to remove the impurities adsorbed on the surface. Finally, the washing with deionised water was repeated42. The pretreated quartz sand underwent thermal drying in an oven at 105℃, followed by cooling and subsequent storage for later use.

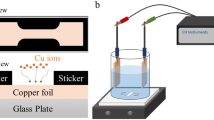

PS-MP/Cu migration experiments in saturated quartz sand columns

A plexiglass sand column 15 cm in height with an inner diameter of 3 cm was selected. The pore volume (PV) was 50 ± 1 mL and the porosity was approximately 0.42. The sand column was filled using the wet method, incorporating a nylon mesh of 50 μm pore size at both the upper and lower extremities of the column43. The lower end of the sand column was connected to a constant-flow pump, the other end of the pump was connected to supply bottles containing different solutions, and the upper portion of the sand column was linked to an automatic sample collector. To mimic a groundwater flow rate of 4 mL/min, a pump maintaining a steady flow rate was employed.

For the PS-MPs, aged PS-MPs, and Cu2+ permeation experiments under background ion-free conditions, a 6 PV solution of deionised water was flowed through the column of sand to ensure equilibrium. Subsequently, a volume of 426.8 mL of the iodide ion tracer solution was fed into the sand column with a PV of 10.4. The column was then washed with 4.6 PV of deionised water and the tracer (Br) concentration was determined using ion chromatography. Subsequently, the sand column was infused with a 6 PV Cu solution. Following that, a blend of 196 mL PS-MPs and Cu was prepared, premixed for 24 h, and placed in a sand column for 4.4 PV. Finally, the column underwent washing with deionised water at 4.6 PV.

Column experiments were carried out to explore the vertical movement of migration behaviour of PS-MPs, aged PS-MPs, and Cu2+ ions in saturated porous media. They included the individual and cotransport of PS-MPs, aged PS-MPs, and Cu2+ in sand columns under different water chemistry conditions (background ions: Na+/Ca2+, pH 4.2). Before the experiment, 6 PV of deionised water was injected from the bottom up using a peristaltic pump to remove air bubbles between the quartz sands in the column, followed by the passage of a 4.6 PV background electrolyte to stabilise the chemical conditions of the solution, and then 10.4 PV of the tracer solution was injected. In the experiment, 3 PV of the same background solution of the PS-MPs/Cu2+ mixture was first passed into the suspension (in consideration of the stability of the suspension, ultrasonic treatment was carried out for 10 min before sampling), and then 3 PV of the background electrolytic solution was passed into the suspension at a flow rate of 4 mL/min, and the effluent was continuously collected by the CBS-A programmed multifunctional and fully automated partial collector (Shanghai Luxi Analytical Instrument Factory, China) at 10-min intervals. Finally, the column with 4.6 PV deionised water. Following the above operation path, individual and cotransport experiments of PS-MPs, aged PS-MPs, and Cu2+ were conducted and the concentrations of MPs and Cu2+ in the effluent were determined using a UV spectrophotometer (SPECORD 200 PLUS, Germany) and a full-spectrum direct-reading inductively coupled plasma-emission spectrometer (Prodigy XP ICP-OES, United States), respectively, to determine the corresponding changes in the MPs and Cu2+ concentrations during the migration process. Penetration curves were obtained.

Characterization

A high-sensitivity zeta potential analyser (ZETA PALS, Brookhaven, USA) was employed to ascertain the zeta potentials of the MPs and quartz sand under different hydrological conditions, and DIVO energy calculations were performed based on the results. Fourier-transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR; Nicolet iS 50, Thermo Scientific, USA) with the pellet pressing method was employed to analyze the changes in functional groups on PS-MPs and aged PS-MPs before and after Cu2+ adsorption44. The surface morphology and primary dimensions of the quartz sand and the deposition of PS-MPs on the quartz sand surface at the mouth of the sand column were observed using scanning electron microscope-energy dispersive spectrometry (SEM-EDS; S-4800, Hitachi, Japan; Fig. 1). MP specimens were characterised using XPS (Thermo Scientific K-Alpha, Thermo Fisher Scientific) to assess the variations in the elemental compositions of their surfaces prior to and following Cu2+ adsorption. The data were fitted using Thermo Advantage V5.9922 software and the binding energy at C1s was calibrated to 284.8 eV.

DLVO calculation

The Derjaguin–Landau DLVO (Derjaguin-Landau-Verwey-Overbeek) theory was used to analyse the effects of various factors. The entire interaction energy between PS-MP particles and between PS-MPs close to the quartz sand surface, as well as the sum of the repulsive electrostatic double layer and gravitational van der Waals forces, is the total interaction energy45. The mutual effect energy between the colloidal particles and the surface of the medium particles corresponded to the vertical coordinates of the DLVO potential energy diagram, whereas the separation distance between them corresponded to the horizontal coordinate. van der Waals forces were calculated using the following equation:

where A is the Hamaker constant for organic particles (6.6 × 10− 21 J), ap is the radius of the colloidal particles, and h is the separation distance between the suspended particles and the surface of the quartz sand. λ is the characteristic wavelength of the colloidal particles (λ = 100 nm).

Hogg et al.46 proposed the following expression for ΦEDL:

where ε0 is the dielectric constant of the vacuum (8.85 × 10− 12 C J− 1 m− 1); εr is the relative dielectric constant of water (82.04); and Ψ1 and Ψ2 are the potentials at the surfaces of the colloidal and dielectric particles, respectively. For the detailed calculation procedure, please refer to Supplementary Data Text S1.

Results and discussion

Characterization of MPs

FTIR spectroscopy was used to detect functional groups on the surfaces of PS, UV-PS, and O3-PS before and after Cu2+ adsorption. The FTIR spectra of the three types of PS before and after the adsorption of Cu2+ are shown in Fig. 2. The surface functional groups containing oxygen on the two types of UV- and O3-aged PS showed an increasing trend and broadened absorption peaks. The key peaks in the FTIR spectrograms for the three varied kinds of PS were compared. The aged PS showed stretching of the key peak at 1630 cm− 1, bending vibration of the characteristic peak at 1498 cm− 1, stretching vibration of the characteristic peak at 3021 cm− 1, and absorption peaks at 1600 and 1376 cm− 1 corresponding to the C = C vibration of the benzene ring and the phenolic hydroxyl group, respectively. the bending vibrations of the phenolic hydroxyl groups. The absorption peaks at 1738 cm− 1 and 3438 cm− 1 correspond to the O-H stretching vibrations of carbonyls, alcohols, and carboxylic acids, respectively, suggesting that the intensities of the characteristic peaks of PS at these two locations slightly increased with ageing. This phenomenon was similar to that observed by25. In the PS characteristic plots before and after Cu2+ adsorption, the C = O bonds on the surface of PS, UV-PS, and O3-PS were altered from 1530 to 1560 cm− 1, 1731 to 1721 cm− 1, and 1734 to 1720 cm− 1, respectively. This indicates that the C = O content on the surfaces of the UV-PS and O3-PS increased after the adsorption of Cu2+ by PS, UV-PS, and O3-PS. Thus, the adsorption of Cu2+ by PS, O3-PS, and UV-PS appears to primarily be electrostatic and the C = O functional group plays an important role.

XPS was employed to analyze the surface functional groups and elemental composition of MPs, both before and after Cu2+ adsorption. Regardless of Cu2+ adsorption, C1s and O1s peaks were consistently observed in the XPS spectra of all MPs. A Cu 3d peak was identified on the surface of MPs after Cu2+ adsorption (Fig. S3). Following Cu2+ adsorption by MPs and aged MPs, the C = O content decreased, as shown in Fig. 3 and S4, suggesting the significant role of the C = O functional group in Cu2+ adsorption47. Post Cu2+ adsorption, the relative atomic percentage of C = O on the surface of MPs and aged MPs increased. This process may induce reactions within the polymer, aligning with FT-IR results and consistent with previous research findings17.

Effects of different ion concentrations/valence states on migration

Individual migration characteristics of MPs

PS migration was influenced by the chemical properties of the solution as illustrated in Fig. 4. With a gradual increment of the background ion concentration, the penetration ability of the PS gradually weakened; the maximum efflux concentration ratios of PS in the Na + and Ca2+ systems decreased from 0.79 to 0.55 to 0.42 and 0.37, respectively, and the penetration rates decreased from 78.7% and 54.5–42.4% and 37%, respectively. Both O3-aged and UV-aged PS showed 17.1%, 43.1%, 16.8%, and 37.8% higher mobilities than PS in Na+ and Ca2+ systems, respectively (Fig. 4). The negative charge and polarity of MPs increased because of the numerous abundant functional groups on the aged PS48, which enhanced the mobility and passage ability of the MPs. Under all conditions, the penetration ability of PS decreased with increased background ion concentrations. This may indicate that a high concentration of background ions caused PS to be adsorbed and deposited on the surface of the quartz sand by a large number of aggregates, causing a progressive diminishment of the ability of PS to penetrate the porous medium. Rising IS of the solution inhibited PS migration, agreeing with prior conclusions, and the increase in IS resulted in lower PS migration in porous media49. Previous studies show that the negative charges of PS and soil decrease with increasing IS, which reduces the repulsion between PS and soil. These results qualitatively agree with the DLVO interaction energy calculations, and the interaction of PS with quartz sand can be effectively described using DLVO. The repulsive abilities of PS and quartz sand exhibited weaker repulsive abilities with rising IA. Thus, the attraction stemming from the weaker electrostatic repulsion between PS and quartz sand led to greater retention of PS. Because of the compression of the bilayer, colloid stability is affected by its surface adsorption and charge potential. In addition, according to the double electric layer theory, PS particles with the same kind of charge on the surface of the greater the number, the stronger the electrostatic repulsion between them, which means that the stability between the particles will improve, and PS particles are not easily adsorbed or precipitated, mobility, and through the good, and vice versa. Owing to the inhibition of the electric double layer of Na+, Ca2+ and other cations, PS can rapidly form millimetre-sized aggregates, reducing the mobility of PS particles45,50,51. In the conduct of this study, owing to the negatively charged PS particles and the electrostatic effect of Na+ and Ca2+ adsorbed in its indication of weakening its indication of electronegativity, the repelling force between the PS particles and the quartz sand becomes weaker. This in turn leads to a reduction in the stability between the PS particles, which are attracted to each other, leading to a reduction in mobility. When the concentrations of Na+ and Ca2+ ions increased from 1 to 10 mmol (Table 1), the zeta potentials (absolute values) of PS decreased by 30.82% and 42.28%, respectively, whereas the zeta potentials of the quartz sand did not show any significant change. The rapid decrease in the electronegativity of PS led to a decrease in its colloidal stability, which aggravated its adsorption and deposition on the surfaces of the quartz sand particles. As shown in Fig S1, when the concentrations of Na+ and Ca2+ were 1 mmol, the DLVO synergistic force between the ageing PS, PS, and quartz sand behaved as a repulsive force. This indicates that the interactions between quartz sand and PS are dominated by an electrostatic repulsive force and that the adsorption of quartz sand on the MPs was somewhat small when the background electrolyte concentration was low. With a gradual increase in ion concentration, the shielding effect of cations on the negative surface charge gradually increased, leading to diminution of the repulsive force between the MPs and quartz sand, and the total potential energy was gradually dominated by the gravitational potential energy composed of van der Waals forces. At this time, PS and quartz sand inside the sand column were attracted to each other and agglomerated, thus blocking a large number of pores in the sand column and hindering PS transportation. When the Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations were 10 mmol because the background IS increased, the cations suppressed the negative charge surface of PS, leading to a mutual attraction between the PS and quartz sand, inhibiting their mobility, and the PS penetration curve appeared to be ripened52. The precipitated PS on the surface of the quartz sand caused massive deposition and clogging by the electrostatic adsorption of more PS. At the same IS, divalent Ca2+ inhibits PS transport more than monovalent Na+. For example, the maximum outflow concentration ratios of PS in quartz sand were 64.1% and 35.7% at 5 mmol IS for NaCl and CaCl2, respectively. The higher retention of PS in CaCl2 than in NaCl at the same IS was caused by the enhanced charge balancing neutralisation of Ca2+ than Na+, and due to the superior efficacy of the divalent cations at neutralising the negative surface charge and suppressing the thickness of the double layer53. Furthermore, the potentials of PS and soil in CaCl2 were conspicuously higher than those in NaCl. In addition, prior research indicates that Ca2+ is more potent at reducing the electrostatic repulsion between PS and soil under the same IS conditions because the energy barrier height in CaCl2 is significantly less than that in NaCl49. Similar findings have been reported for other colloidal particles in porous media54,55.

Migration characteristics of PS-MPs at different concentrations under ion-free conditions

As the concentration of PS-MPs increased (10, 20,30 mg/L), the migratory properties of the maximum and peak gradually increased from 89 to 97% (Fig. 5)56 and57 found that more nanoparticles passed through a porous medium as the PS-MPs concentration increased. The migration rate of aged PS is higher compared to that of unaged PS. This is because the C = O content on the surface of the aged PS-MPs increased the polarity and electrostatic repulsion of MPs, whereas the elevated mobility of the MPs may be due to the insignificant impact of MP particles at low flow rates. Despite the increased input concentration, only a mere handful of MP particles were intercepted by the quartz sand owing to particle collisions. Moreover, the point of interception on the surface of the quartz sand was limited and with a gradual increase in input concentration, only a small proportion of the PS-MPs were intercepted in the column, and most of the remaining PS-MPs penetrated out of the sand column. The difference in migration rates between O3-aged PS and UV-aged PS is less pronounced, primarily because both O3 and UV oxidation introduce polar functional groups to the surface of the particles58. The increased surface roughness and porosity from UV oxidation can provide more physical sites for adsorption, potentially increasing capacity59. The chemical changes from O3 oxidation can enhance interactions with specific pollutants, especially those that form hydrogen bonds or electrostatic interactions with the introduced functional groups60.

Therefore, the MPs exhibited relatively good transport behaviour when the injected concentration increased. This shows that although the porous medium has some filtration effect, there are still a large number of PS-MPs that are difficult to intercept and release into groundwater.

Characterisation of the individual transport of Cu2+ and its mechanisms of influence

Cu2+ penetration was weaker in solutions without background ions than in solutions with background ions (Fig. 6). The background ion concentrations and types can significantly affect the mobility of Cu2+ (Fig. 6). As the increased concentration of Na + in the background electrolyte from 1 to 10 mmol/L, the maximum efflux rate of Cu2+ increased from 0.67 to 0.77 and the penetration rate increased from 67.3 to 77.3%. This indicated that the adsorption capacity of the medium for Cu2+ continuously weakened, and that the concentration of the background ions and the penetration rate of Cu2+ were varies linearly with the concentration of the background ions, and that more Cu2+ were able to penetrate the quartz sand column. The penetration ability of Cu2+ is weakest when the ion concentration is 1 mmol/L; the quartz sand indicates that negatively and positively charged Cu2+ is easily adsorbed to the quartz sand due to electrostatic interaction. The penetration of Cu2+ was greatest when the background ion concentration was 10 mmol/L. As the IS increased, the free Na+ and Ca2+ in the electrolyte solution gradually increased, inhibiting the negative charge on the surface of the quartz sand and weakening its electrostatic adsorption capacity for Cu2+. In contrast, when Cu2+ migrated into Ca2+ the penetration rate of Cu ions was close to 1 (Fig. 6), and the enhancement in the mobility of Cu2+ was not evident, indicating that Cu ions were not retained in the quartz sand column. It may be owing to the fact that quartz sand has fewer adsorption sites and the adsorption sites are occupied by cations. Moreover, Na+ and Ca2+ compete for adsorption on quartz sand and because of the high concentration of cations, Cu2+ adsorbed on quartz sand is desorbed from the new free state and continues to migrate61.

Characterisation of Cu2+ and PS-MP co-migration under different solution conditions and their mechanisms of influence.

Effects of IS

The influence of different IS on Cu2+ migration in each system and Cu2+ adsorption on the PS-MPs are influenced by background ions in the solution. IS (1, 5, 10 mM) and coexisting cations, such as Ca2+ and Na+, affect the adsorption sites, as shown in Fig. 7a-d. For example (Fig. 7), the adsorption of Cu2+ by PS-MPs decreased as the IS concentration increased, and the concentration of Na+ and Ca2+ increased from 1 to 10 mmol/L, the maximum efflux rate of Cu2+ increased from 0.75 to 0.85 to 0.86 and 0.98, and the penetration rate increased from 75.9% and 85.8–84.3% and 98.4%, each corresponding to the original and new values. This implies that the adsorbent capacity of the medium for Cu2+ was weakened, more Cu2+ could penetrate the quartz sand columns, and the increased ion concentration of the background was positively correlated with the migration capacity of Cu2+. This is consistent with previous reports in which the migration of rising IS boosts the movement of other metal cations through porous media62. At increasing cation concentrations, the negative charges indicated by the particles are neutralised, resulting in stronger electrostatic repulsion, which greatly enhances the repulsive force existing between the quartz sand and the Cu2+ surface. In contrast, the adsorption areas on the quartz sand surface promoted Cu2+ transport owing to competition between cations and Cu2+. Prior research indicates that found that negatively charged colloidal particles on the surface promote the transport of uranium in quartz sand, thereby increasing its contamination63. Overall, PS-MPs promoted Cu2+ transport in the following order: O3-aged MPs > UV-aged MPs > MPs. These results indicate that aging PS-MPs are stronger carriers of Cu2+ than PS-MPs. PS-MPs and aged PS-MPs not only had high adsorption capacities but also high adsorption capacities. The lowest mobility of MPs at an IS of 10 mmol may be because MPs adsorb and agglomerate with cations in large quantities in the ionic environment at high concentrations, thereby clogging up the quartz sand and thus further reducing their mobility43. observed a similar phenomenon. A significant amount of C = O functional groups on PS-MPs and aged PS-MPs can promote the negative charge and polarity of the MPs surface48. In particular, negative charges on MPs and mutual attraction between heavy metal ions through electrostatic interactions are essential for migration64. Earlier research also demonstrates that the O-functional groups on MPs are important players in the adsorption and migration of metal ions17. Therefore, more Cu2+ is adsorbed by the aged PS-MPs through surface complexation and electrostatic adsorption. Combined with the aforementioned findings, the aged PS-MPs were determined to be better carriers of Cu 2+.

Effects of Cu2+ and PS on each other

PS effectively enhanced the Cu2+ breakthrough ability (Fig. 7). However, the negatively charged Cu2+-MP complexes enhanced the repulsive force between some of the Cu2+ ions and the quartz sand, hindering the retention of Cu2+ in the porous medium. This reduced the Cu2+ adsorption on the surface of the quartz sand owing to the competition between dispersed positively charged particles in the Cu2+ water solution and the surface of the quartz in the presence of Na+ and Ca2+. In contrast, the DLVO curve exhibits a significant energy potential hurdle that enables the particles to surpass the effects of Brownian motion and facilitate their transportation. (Supplementary Fig. 2). By comparing the penetration curves of MPs in the solo transport (Fig. 5) and cotransport (Fig. 7) systems, It is observable that the maximum efflux concentration ratios and penetration rates in the cotransport system were lower than the corresponding maximum efflux concentration ratios and penetration rates in the single system under the same conditions. This indicates a significant decrease in the penetration ability of MPs with Cu2+ coexistence, as evidenced by65 and66. No new characteristic peaks emerged or vanished after the adsorption of Cu2+ by PS. The significant decrease in the penetration ability of PS could be explained by the fact that the positively charged Cu2+ adsorbed on the surface of the PS bridged the negatively charged sites on the PS surface and quartz sand, increasing the PS adsorbed and deposited on the surface of the quartz sand, causing clogging. The zeta potential in the co-migration system is lower than that in the PS-alone migration system, which implies that the presence of Cu2+ causes the zeta potential of PS to be closer to a positive value, which reduced the repulsive potential barriers dominated by electrostatic forces between PS particles and between PS and quartz sand, having the consequence of more PS being deposited on the surface of the quartz sand, which further inhibits its transport ability67. Furthermore, the adsorption of Cu2+ by PS also improved its migration ability in environmental media68. The corresponding maximum efflux concentration ratio, and the penetration rate of Cu2+ in the co-migrating system under the same conditions was higher than that of the corresponding maximum efflux concentration ratio and penetration rate in the single system (Fig. 8). This indicates that the existence of MPs can increase the movement ability of Cu2+ in porous media, expanding its contamination range and that PS loading of Cu2+ is an important pathway for its migration. The increased mobility of Cu2+ in the co-migration system of O3-aged PS and Cu2+ is due to O3 interacting with the surface of MPs, introducing oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, and carbonyl groups. This can significantly alter the surface chemistry, increasing hydrophilicity and potentially enhancing the adsorption capacity for certain pollutants69. However, in the co-migration system of UV-aged PS and Cu2+, the increased mobility of Cu2+ is primarily due to UV radiation-induced photo-oxidative degradation. This process leads to the breakdown of polymer chains and the formation of free radicals and oxygen-containing groups. Additionally, it often causes surface roughening and the formation of microcracks in microplastics, thereby increasing the surface area available for Cu2+ adsorption70. Earlier research has demonstrated that heavy metals can be adsorbed onto MPs through physical electrostatic interactions, chemical adsorption, and surface complexation, and that mobility also affects their adsorption71.

Effect of cations

The influence of cations of different valence states on the physicochemical properties of particles is essential for the cotransport of Cu2+-MPs72. Cu2+-MPs concurrent transport studies were carried out in porous media with the addition of Na+ and Ca2+ with a gradual increase in IS (1, 5, and 10 mmol). In a separate transport system, Cu2+ transport was enhanced by increasing the coexisting cation valence. In the binary system, the high-valence background ions inhibited the transport of MPs and promoted the migration of Cu2+, as shown in Fig. 7; The Cu2+ and PS mobilities increased by 10.9% and decreased by 11%, respectively, at an IS of 1 mmol. The strength of the adsorption power of MPs and quartz sand for metal cations is primarily influenced by the hydration ion radius; the narrower the hydration radius, the more pronounced the adsorption effect73. Since the hydration radius of Cu2+ is larger than Ca2+, it can be seen that the adsorption capacity of quartz sand and MP for Ca2+ is stronger than that of Cu2+, and the migration capacity of Cu2+ ions is enhanced in the porous medium. This led to more pronounced Cu2+ migration when Ca2+ was present compared to when Na+ was present. This leads to the conclusion that Ca2+ has a stronger facilitating effect on Cu2+ migration in porous media than Na+, which is similar to results observed by Shi et al.74. Ca2+ reduced the maximum mobility of PS, O3-aged PS, and UV-aged PS by 11.05%, 3.9%, and 3.19%, respectively, compared to Na+. Where the decrease in the maximum mobility of aged MPs in Ca2+ versus Na+ was not significant may be due to the fact that aging intensifies the polarity of MPs thereby facilitating the migration of MPs. Compared to the penetration curves of the migration test (Fig. 7), the inhibition of PS migration by Cu2+ in MPs-Cu2+ and aged PS-Cu2+ was weaker in the Ca2+ system. The suppressive impact of Cu2+ on the PS transport ability in the Ca2+ system was significantly weakened because of compression of the bilayer, stronger competitiveness of the surface adsorption sites, and negative charge inhibition compared with that of Na+. In contrast, the migration inhibition of aged MPs by the Ca2+ and Na+ systems in aged PS-Cu2+ was not significant. In the absence of ions (Fig. 7), PS and aged PS adsorbed Cu2+, increasing the Cu2+ transport in the porous medium. However, when multivalent cations were present and the MPs were aging, the facilitation of Cu2+ transport by MPs was not significant. The recovery of Cu2+ by PS, UV-aged PS, and O3-aged PS was only 13%, 2.55%, and 3.12% higher, respectively, than that of Na+ when Ca2+ is present at an IS of 10 mmol (Fig. 7). This could potentially be due to the fact that the adsorption of Cu2 + onto MPs diminishes as cationic valence increases, in which case the carrying capacity of MPs was limited, and a large number of cations caused led to the accumulation of Cu2+-MPs on quartz sand75. Ca2+, which possess greater ionic radii, possess smaller radii of hydration and greater charge-shielding capacities than Na+75. In contrast, the cations occupied the adsorption sites on the quartz sand, indicating the suppression of negative charges49. Despite the existence of energy barriers in the DLVO curves (Supplementary Fig. 2), the transport of Cu2+-MPs was inhibited. Therefore, the synergistic transport of Cu2+ and MPs poses a serious challenge to environmental safety.

Conclusion

Although MP contamination of soil and groundwater environments has been intensively studied, the synergistic transport of aged MPs and heavy metals is remains insufficiently comprehended. In this research, the ionic valences and concentrations of PS-Cu2+ and aged PS-Cu2+ in porous media were assessed for individual transport and cotransport behaviours to explore the differences in their interactions. Ca2+ divalent cations are more effective than Na+ in neutralising negative surface charges and suppressing the extent of the double electrical layer. In both individual and synergistic transport systems, the increment in IS decreased the negative charge, as indicated by the PS and quartz sand. This reduced the repulsion and stability between PS and quartz sand, enabling PS to rapidly form millimetre-sized aggregates. A large number of these aggregates can be adsorbed and deposited on the surface of the quartz sand, which reduces the migratory properties of the PS particles. Besides the influence of IS and valence, the effects of ageing on different MPs need to be considered. Ageing MPs can further promote the migration of Cu2+ and greatly improve the mobility of MPs in high-concentration ionic environments because a large number of functional group bond breaks enhance their polarity and electrostatic interactions enhance the complexation force. Ca2+ reduced the electrostatic repulsion and mobility between PS and quartz sand more effectively than Na+. The increase in IS can increase the charge shielding effect, as indicated by quartz sand when Cu2+ is transported alone, which further increases the mobility of Cu2+ because of its stronger negative charge inhibition and spot adsorption ability. Thus, Cu2+ possesses stronger mobility in the Ca2+ system with identical IS. The transport of Cu2+ was greater in binary transport systems than in individual transport systems. However, the charge inhibition indicated by the cations for the MPs and the competition for adsorption sites further weakened the transport ability of PS for Cu2+ because of the increase in background IS and the adsorption site limitations for MPs. Thus, the impact of flow velocity on migration in the co-migrating system requires further investigation. Overall, the MPs and aged MPs played key roles in facilitating Cu2+ transport and ageing had a substantial influence on the transport enhancement of MPs and PS-Cu2+. In this research, we anticipated the potential environmental hazards posed by Cu2 + and aged MP contamination in soil and groundwater.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jiao Fei et al. Co-transport of degradable microplastics with cd(II) in saturated porous media: Synergistic effects of strong adsorption affinity and high mobility. Environ. Pollut. (2023).

Wagner, M. et al. Microplastics in freshwater ecosystems: What we know and what we need to know. Environ. Sci. Eur. 26(1), 12 (2014).

Liu Tongyao, X., Yi, L., Xingzhong, W. & Bing Meichun, X. Advances in microbial degradation of plastics. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 38, 2688–2702 (2021).

Huang, D., Xu, Y., Yu, X., Ouyang, Z. & Guo, X. Effect of cadmium on the sorption of tylosin by polystyrene microplastics. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 207, 111255 (2021).

Zhang, G. S. & Liu, Y. F. The distribution of microplastics in soil aggregate fractions in southwestern China. Sci. Total Environ. 642, 12–20 (2018).

Liao, J. & Chen, Q. Biodegradable plastics in the air and soil environment: Low degradation rate and high microplastics formation. J. Hazard. Mater. 418, 126329 (2021).

Mintenig, S. M., Löder, M. G. J., Primpke, S. & Gerdts, G. Low numbers of microplastics detected in drinking water from ground water sources. Sci. Total Environ. 648, 631–635 (2019).

Carpenter, E. J. & Smith, K. L. Plastics on the Sargasso sea surface. Science 175(4027), 1240–1241 (1972).

Koelmans, A. A., Bakir, A., Burton, G. A. & Janssen, C. R. Microplastic as a vector for chemicals in the aquatic environment: Critical review and model-supported reinterpretation of empirical studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50(7), 3315–3326 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Polystyrene nanoplastics-enhanced Contaminant Transport: Role of irreversible adsorption in glassy polymeric domain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52(5), 2677–2685 (2018).

Acarer, S. A review of microplastic removal from water and wastewater by membrane technologies. Water Sci. Technol. 88(1), 199–219 (2023).

Zhang, S., Han, B., Sun, Y. & Wang, F. Microplastics influence the adsorption and desorption characteristics of cd in an agricultural soil. J. Hazard. Mater. 388, 121775 (2020).

Camacho, M. et al. Organic pollutants in marine plastic debris from Canary Islands beaches. Sci. Total Environ. 662, 22–31 (2019).

Jang, M. et al. Styrofoam debris as a source of Hazardous additives for Marine organisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50(10), 4951–4960 (2016).

Silva, P. P. G., Nobre, C. R., Resaffe, P., Pereira, C. D. S. & Gusmao, F. Leachate from microplastics impairs larval development in brown mussels. Water Res. 106, 364–370 (2016).

Chen, M., Xu, N., Christodoulatos, C. & Wang, D. Synergistic effects of phosphorus and humic acid on the transport of anatase titanium dioxide nanoparticles in water-saturated porous media. Environ. Pollut. 243, 1368–1375 (2018).

Zhou, Y., Yang, Y., Liu, G., He, G. & Liu, W. Adsorption mechanism of cadmium on microplastics and their desorption behavior in sediment and gut environments: The roles of water pH, lead ions, natural organic matter and phenanthrene. Water Res. 184, 116209 (2020).

Guan, J. et al. Microplastics as an emerging anthropogenic vector of trace metals in freshwater: Significance of biofilms and comparison with natural substrates. Water Res. 184, 116205 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Modifications to sorption and sinking capability of microplastics after chlorination. Water Supply 23(8), 3046–3060 (2023).

Kiki, C. et al. Induced aging, structural change, and adsorption behavior modifications of microplastics by microalgae. Environ. Int. 166, 107382 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. Observation of colloidal particle deposition during the confined droplet evaporation process. Acta Phys. Sinica 64(9), 096101–096101 (2015).

Xi, X. et al. Interactions of pristine and aged nanoplastics with heavy metals: Enhanced adsorption and transport in saturated porous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 437, 129311 (2022).

Song, Y. K. et al. Combined effects of UV exposure duration and mechanical abrasion on Microplastic Fragmentation by Polymer Type. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51(8), 4368–4376 (2017).

Wang, K. et al. Adsorption–desorption behavior of malachite green by potassium permanganate pre-oxidation polyvinyl chloride microplastics. Environ. Technol. Innov. 30, 103138 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Aging significantly affects mobility and contaminant-mobilizing ability of nanoplastics in saturated loamy sand. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53(10), 5805–5815 (2019).

Huffer, T., Weniger, A. K. & Hofmann, T. Sorption of organic compounds by aged polystyrene microplastic particles. Environ. Pollut. 236, 218–225 (2018).

Zhu, K. et al. Formation of environmentally persistent free radicals on Microplastics under Light Irradiation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53(14), 8177–8186 (2019).

Briffa, J., Sinagra, E. & Blundell, R. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and their toxicological effects on humans. Heliyon 6(9), e04691 (2020).

Cao, Y. et al. A critical review on the interactions of microplastics with heavy metals: Mechanism and their combined effect on organisms and humans. Sci. Total Environ. 788, 147620 (2021).

Lin, L. et al. Accumulation mechanism of tetracycline hydrochloride from aqueous solutions by nylon microplastics. Environ. Technol. Innov. 18, 100750 (2020).

Chen, Y., Li, J., Wang, F., Yang, H. & Liu, L. Adsorption of tetracyclines onto polyethylene microplastics: A combined study of experiment and molecular dynamics simulation. Chemosphere 265, 129133 (2021).

Sparks, D. L. Toxic metals in the environment: the role of surfaces. Elements 1(4), 193–197 (2005).

Bao, R., Fu, D., Fan, Z., Peng, X. & Peng, L. Aging of microplastics and their role as vector for copper in aqueous solution. Gondwana Res. 108, 81–90 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Heavy metals in the plastisphere of marine microplastics: Adsorption mechanisms and composite risk. Gondwana Res. 108, 171–180 (2022).

Liu, H., Zhen, Y., Zhang, X. & Dou, L. Inhibitory effect of combined exposure to copper ions and polystyrene microplastics on the growth of Skeletonema costatum. 16(16), 2270 (2024).

Liu, Z., Sang, J., Zhu, M., Feng, R. & Ding, X. Prediction and countermeasures of heavy metal copper pollution accident in the Three Gorges Reservoir Area. J. Hazard. Mater. 465, 133208 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Adsorption behavior of aniline pollutant on polystyrene microplastics. Chemosphere 323, 138187 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Degradation of nano-sized polystyrene plastics by ozonation or chlorination in drinking water disinfection processes. Chem. Eng. J. 427, 131690 (2022).

Watson, G. J., Pini, J. M. & Richir, J. Chronic exposure to copper and zinc induces DNA damage in the polychaete Alitta virens and the implications for future toxicity of coastal sites. Environ. Pollut. 243, 1498–1508 (2018).

Fei, J. et al. Transport of degradable/nondegradable and aged microplastics in porous media: Effects of physicochemical factors. Sci. Total Environ. 851, 158099 (2022).

Li, M., He, L., Zhang, X., Rong, H. & Tong, M. Different surface charged plastic particles have different cotransport behaviors with kaolinite ☆particles in porous media. Environ. Pollut. 267, 115534 (2020).

Zhou, D., Wang, D., Cang, L., Hao, X. & Chu, L. Transport and re-entrainment of soil colloids in saturated packed column: Effects of pH and ionic strength. J. Soils Sedim. 11(3), 491–503 (2011).

Hou, J. et al. Transport behavior of micro polyethylene particles in saturated quartz sand: Impacts of input concentration and physicochemical factors. Environ. Pollut. 263, 114499 (2020).

Faghihzadeh, F., Anaya, N. M., Schifman, L. A. & Oyanedel-Craver, V. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy to assess molecular-level changes in microorganisms exposed to nanoparticles. Nanatechnol. Environ. Eng. 1(1), 1 (2016).

Li, Y. et al. Interactions between nano/micro plastics and suspended sediment in water: Implications on aggregation and settling. Water Res. 161, 486–495 (2019).

Hogg, R., Healy, T. W. & Fuerstenau, D. W. Mutual coagulation of colloidal dispersions. Trans. Faraday Soc. 62, 1638–1651 (1966).

Wang, H. et al. Adsorption of tetracycline and cd(II) on polystyrene and polyethylene terephthalate microplastics with ultraviolet and hydrogen peroxide aging treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 845, 157109 (2022).

Tang, S., Lin, L., Wang, X., Yu, A. & Sun, X. Interfacial interactions between collected nylon microplastics and three divalent metal ions (Cu(II), ni(II), zn(II)) in aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater. 403, 123548 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Transport of polystyrene nanoplastics in natural soils: Effect of soil properties, ionic strength and cation type. Sci. Total Environ. 707, 136065 (2020).

Quik, J. T. K., Velzeboer, I., Wouterse, M., Koelmans, A. A. & van de Meent, D. Heteroaggregation and sedimentation rates for nanomaterials in natural waters. Water Res. 48, 269–279 (2014).

Dong, Z. et al. Cotransport of nanoplastics (NPs) with fullerene (C60) in saturated sand: Effect of NPs/C60 ratio and seawater salinity. Water Res. 148, 469–478 (2019).

Dong, Z. et al. Role of surface functionalities of nanoplastics on their transport in seawater-saturated sea sand. Environ. Pollut. 255, 113177 (2019).

Li, S. et al. Aggregation kinetics of microplastics in aquatic environment: Complex roles of electrolytes, pH, and natural organic matter. Environ. Pollut. 237, 126–132 (2018).

Sasidharan, S., Torkzaban, S., Bradford, S. A., Dillon, P. J. & Cook, P. G. Coupled effects of hydrodynamic and solution chemistry on long-term nanoparticle transport and deposition in saturated porous media. Colloids Surf. A 457, 169–179 (2014).

Wang, D., Jaisi, D. P., Yan, J., Jin, Y. & Zhou, D. Transport and retention of polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanoparticles in natural soils. Vadose Zone J. 14(7), vzj2015010007 (2015).

Kasel, D. et al. Transport and retention of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in saturated porous media: Effects of input concentration and grain size. Water Res. 47(2), 933–944 (2013).

Wang, C. et al. Retention and Transport of Silica Nanoparticles in Saturated Porous Media: Effect of Concentration and particle size. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46(13), 7151–7158 (2012).

Ju, H., Yang, X., Osman, R. & Geissen, V. The role of microplastic aging on chlorpyrifos adsorption-desorption and microplastic bioconcentration. Environ. Pollut. 331, 121910 (2023).

Fan, X. et al. Investigation on the adsorption and desorption behaviors of antibiotics by degradable MPs with or without UV ageing process. J. Hazard. Mater. 401, 123363 (2021).

Giamalva, D. H., Church, D. F. & Pryor, W. A. Kinetics of ozonation. 5. Reactions of ozone with carbon-hydrogen bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 108(24), 7678–7681 (1986).

Tang, S., Lin, L., Wang, X., Feng, A. & Yu, A. Pb(II) uptake onto nylon microplastics: Interaction mechanism and adsorption performance. J. Hazard. Mater. 386, 121960 (2020).

Yao, J. et al. Cotransport of thallium(I) with polystyrene plastic particles in water-saturated porous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 422, 126910 (2022).

Brennecke, D., Duarte, B., Paiva, F., Caçador, I. & Canning-Clode, J. Microplastics as vector for heavy metal contamination from the marine environment. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 178, 189–195 (2016).

Mao, R. et al. Aging mechanism of microplastics with UV irradiation and its effects on the adsorption of heavy metals. J. Hazard. Mater. 393, 122515 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Surfactant-induced adsorption of pb(II) on the cracked structure of microplastics. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 621, 91–100 (2022).

Davranche, M. et al. Are nanoplastics able to bind significant amount of metals? The lead example. Environ. Pollut. 249, 940–948 (2019).

Akdogan, Z. & Guven, B. Microplastics in the environment: A critical review of current understanding and identification of future research needs. Environ. Pollut. 254, 113011 (2019).

Cox, K. D. et al. Human consumption of microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53(12), 7068–7074 (2019).

Zhang, X., Lin, T. & Wang, X. Investigation of microplastics release behavior from ozone-exposed plastic pipe materials. Environ. Pollut. 296, 118758 (2022).

Wang, Z. et al. Sorption of selected pharmaceutical compounds on polyethylene microplastics: Roles of pH, aging, and competitive sorption. Chemosphere 307, 135561 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Co-transport of pb(II) and oxygen-content-controllable graphene oxide from electron-beam-irradiated graphite in saturated porous media. J. Hazard. Mater. 375, 297–304 (2019).

Holmes, L. A., Turner, A. & Thompson, R. C. Interactions between trace metals and plastic production pellets under estuarine conditions. Mar. Chem. 167, 25–32 (2014).

Zhu, G., Yue, K., Ni, X., Yuan, C. & Wu, F. The types of microplastics, heavy metals, and adsorption environments control the microplastic adsorption capacity of heavy metals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(33), 80807–80816 (2023).

Shi, K. et al. Impact of Heavy Metal Cations on Deposition and Release of Clay Colloids in Saturated Porous Media (2022).

Cai, L. et al. Effects of inorganic ions and natural organic matter on the aggregation of nanoplastics. Chemosphere 197, 142–151 (2018).

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under the “Research on the mechanism of synergistic fate of dissolved organic matter and heavy metals during underground storage of reclaimed water” No. 51408259, the Science and Technology Development Planning Project of Jilin Provincial Department of Science and Technology under the “Identification and control method of prioritized organic micropollutants in underground storage system of reclaimed water” No. 20220101177JC, and the “Calcium peroxide-sodium peroxide synergistic in-situ technology in PAH contaminated sites” No. 20230203163SF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Writing-original draft, Investigation, Sampling, Formal analysis and Data analysis by [Wang Z]. Writing, Conceptualization, Review, Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition by [ Meng Q]. Sampling and Data analysis by [Shi F]. Investigation and Sampling by [Sun K] and [Wen Z] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, Q., Wang, Z., Shi, F. et al. Effect of background ions and physicochemical factors on the cotransport of microplastics with Cu2+ in saturated porous media. Sci Rep 14, 27101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78480-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78480-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The evolving interface of aged microplastics and heavy metals: implications for environmental fate and toxicity

Environmental Geochemistry and Health (2026)

-

Biochar Offsets Microplastic-Induced Cadmium Mobilization and Plant Accumulation in Contaminated Soils

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2026)