Abstract

The impact of climate change on agricultural production is apparent due to declining irrigation water availability vis-à-vis rising drought stress, particularly affecting summer crops. Growing evidence suggests that zinc (Zn) supplementation may serve as a potential drought stress management strategy in agriculture. Field studies were conducted using soybean (Glycine max var. Saba) as a model crop to test whether foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) or conventional Zn fertilizer (ZnSO4) would mitigate drought-related water stress and improve soybean yield. Each fertilizer was foliar applied twice at a two-week interval during the flowering stage. Experiments were concurrently conducted under non-drought conditions (70% field capacity) for comparison. Results showed drought significantly reduced relative water content, chlorophyll-a, and chlorophyll-b in untreated control plants by 35.7%, 47.7%, and 41.4%, respectively, compared to non-drought conditions (p < 0.05). Under drought conditions, ZnO-NPs (200 mg Zn/L) led to 33.1% and 20.7% increase in chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b levels, respectively, compared to ZnSO4 at 400 mg Zn/L. Likewise, catalase, peroxidase and superoxide dismutase activities increased by 62.6%, 39.5% and 28.5%, respectively, with ZnO-NPs (200 mg Zn/L) under drought compared to non-drought conditions. Proline was significantly increased under drought but was remarkably suppressed (~ 54% lower) with ZnO-NPs (200 mg Zn/L) treatment. More importantly, the highest seed yield was observed with ZnO-NPs (200 mg Zn/L) treatment under drought (39% higher than untreated control) and non-drought (79.4% higher than control) conditions. Overall, the findings suggest that ZnO-NPs could promote seed yield in soybean under drought stress via increased antioxidant activities, increased relative water content, decreased stress-related proline content, and increased photosynthetic pigments. It is recommended that foliar application of 200 mg Zn/L as ZnO-NPs could serve as an effective drought stress management strategy to improve soybean yield.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr) is an important legume and food crop globally. Soybean seeds are rich in nutrients, comprising 20% oil1, 35–40% protein, and a variety of essential amino acids2 that are vital for promoting human nutrition and health3. Recognized as a superior source of vegetable protein, soybean sets a standard for other vegetable protein sources4. Moreover, it serves as an exceptional source of carbohydrates and essential nutrients such as copper, zinc, calcium, magnesium, iron, manganese, and phosphorus for human and animal consumption5. Through symbiosis with Bradyrhizobium japonicum, soybean fixes nitrogen from atmosphere6, thereby aiding in reducing reliance on nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture.

More than 25% of the Earth’s surface is classified as arid and semi-arid, with approximately 33% of arable land facing water scarcity7. Drought is the primary constraint to agricultural productivity in these regions. The increased frequency of drought events due to climate change poses a significant challenge to ensuring food security for the ever-growing human population8. Among various stressors affecting crops, drought stress exerts the most pronounced negative impact on crop yield and nutritional quality. Diminished grain yield and food quality due to drought stress contribute to food and nutritional insecurity. For instance, soybean yield and quality are reduced under drought stress, with the extent of reduction influenced by stress intensity, duration, genotype, and growth stage9,10. Drought stress impedes water and nutrient uptake, leaf water status, gas exchange, and overall crop productivity11. Moreover, reduced stomatal conductance under drought elevates leaf temperature, resulting in wilting12. Water deficit exacerbates membrane permeability, nutrient absorption, and chlorophyll synthesis, reducing photosynthetic efficiency in plants13. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated under drought stress can damage plant cell membranes and essential molecules like proteins and lipids14. Increased accumulation of hydrogen peroxide, malondialdehyde, and electrolyte leakage has been observed in various plant species subjected to different stressors15,16.

Plants mitigate the adverse effects of drought stress by initiating antioxidant defense mechanisms, which play a crucial role in the removal of ROS17. The defense mechanism involves the accumulation of osmolytes, such as proline and vitamins in cytosol, as a protective shield against ROS-induced oxidative stress18. Furthermore, plants’ defense system comprises antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and catalase19. Zinc (Zn), as a micronutrient, is essential for various plant growth processes and physiological and biochemical functions. These include protein synthesis, chlorophyll synthesis, and enzyme activity20. Zinc also contributes to the stability of cell membrane, cytochrome synthesis, and photosynthesis. Additionally, it plays a crucial role as a component of carbonic anhydrase and as a stimulant for aldolase, both the enzymes involved in carbon metabolism21. Moreover, Zn is integral to biological molecules like lipids and proteins, significantly impacting plant nucleic acid metabolism22. Consequently, Zn supplementation is recommended for promoting soybean yield23.

It is imperative to explore novel techniques that can improve agricultural production in water-stressed conditions. One such method involves the utilization of micronutrients such as Zn. Research has shown that Zn can mitigate the negative impact of drought stress in plants24. Dimkpa et al.25 found that application of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) in soil (1–5 mg/kg) could improve sorghum growth and yield under water stress. Additionally, it enhanced the levels of N, K, and Zn. The study revealed that grain production increased significantly compared to control, depending on the concentration of ZnO-NPs. Vaqhar et al.26 also investigated the impact of drought stress in soybean and observed a reduction in seed yield. Foliar spraying of Zn nanochelates significantly promoted plant resistance to drought stress. Soybean plant treated with Zn nanochelates led to a 31.7% increase in yield compared to control. Another study that involved seed priming followed by foliar application of ZnO-NPs showed increased chlorophyll and relative water content in rice27.

Nano fertilizers have been shown to enhance nutrient uptake efficiency in plants, particularly in semi-arid regions susceptible to drought28,29. The use of nano fertilizers can lead to a reduction in fertilizer consumption compared to traditional fertilizers, thereby mitigating environmental pollution. We hypothesized that the application of ZnO-NPs would improve the photosynthetic activity and overall performance of plants by promoting antioxidant defense system. In this study, we investigated the potential impact of ZnO-NPs in soybean under drought conditions over a 120-day growth period in the field environment.

Materials and methods

Material characterization

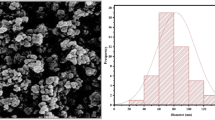

ZnO-NPs and zinc sulfate (ZnSO4) were purchased from Pishgaman Nanomaterials and Kargozar companies, Iran, respectively. The mean particle size of the ZnO-NPs was determined by tunneling electron microscopy (TEM) and hydrodynamics diameter and zeta potential were measured by dynamic light scattering. The TEM micrograph (Fig. 1a) showed particles were spherical with mean particle size of 20 nm. The phase purity and crystal structure of the ZnO-NPs were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) in the scanning angle range of 2θ = 25º–75º using Philips X’Pert PRO X-ray diffractometer and Cu-Kα X-ray source (λ = 1.5406 Å). A summary of obtained structural parameters is presented in Table 1. The Rietveld analysis of the XRD pattern using Fullprof software showed that ZnO-NPs are crystallized in triclinic structure without any trace of impurities (Fig. 1b). The dynamic light scattering indicates mean zeta potential of -34 mV and hydrodynamic diameter of about 388 nm.

Study location

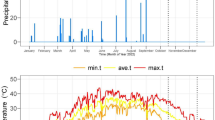

The research was conducted at Shahrekord University’s agricultural research farm located at a latitude of 32 degrees and 21 min north, a longitude of 50 degrees and 49 min east, and an altitude of 2050 m above the sea level. Detailed information regarding the climate and soil characteristics are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The study location lacked rainfall during the study period, allowing us to mimic drought condition. Furthermore, the low levels of organic matter and pH in the soil suggested limited availability of micronutrient elements, such as Zn.

Experimental design

The experiment followed a factorial randomized complete block design with three replications. The first factor consisted of two levels of water availability: no drought (70% of field capacity) and drought (40% of field capacity). The second factor included different concentrations of ZnO-NPs (0, 50, 100, and 200 mg Zn/L) and zinc sulfate (400 mg/L). For ZnSO4, a concentration of 400 mg Zn/L was chosen to represent conventional Zn fertilizer commonly used by farmers. The highest concentration of ZnO-NPs (200 mg Zn/L), equivalent to 50% of the typical Zn fertilizer, was selected based on the growth-promoting effects of nano-Zn based fertilizers as reported by previous studies30,31 and to compare its effects with ZnSO4.

Ten-liter containers were used for cultivation. To ensure proper aeration, 500 g of pebbles were placed at the bottom of each container. Subsequently, a plastic bag with 50 holes of 5 mm diameter was inserted into each container to facilitate plant harvesting. A leveling hose was also inserted into each container to ensure adequate root aeration. Each container was filled with 10 kg of soil. The containers were then positioned in deep furrows in a row, and the surrounding area was covered with soil to align the surface of each container with the field soil (Fig. S1). Before planting, one g per kg triple superphosphate fertilizer was mixed with the soil in the container. Additionally, three g per kg urea was added to each container thrice (14, 35, and 56 days post-planting). Glycine max (var. Saba) seeds were acquired from Karaj Seed and Plant Breeding Research Institute. Seeds were soaked in distilled water for 24 h, briefly placed in a moist cloth at room temperature, and the seeds were immersed in a suspension of B. japonicum for 30 min before sowing. On June 16, 2021, two seeds of uniform size were planted in each container at a depth of 2.5 cm, followed by immediate irrigation. Treatment solutions were prepared and homogenized with a vortex, and 200 ml solution was sprayed on to the foliage during the stem formation stage of soybean (54 days post-sowing). Spraying was repeated the following week. Drought stress was imposed one week after the second spray and continued until the end of the growth period. Plants were harvested when the leaves and pods turned yellow.

Measurement of photosynthetic and physiological traits

Young leaf samples were collected at 96 days post-sowing from the middle part of the plant to assess physiological and biochemical characteristics. The technique described by Lichtenthaler and Buschmann32 was used to quantify the photosynthetic pigments: chlorophyll-a, chlorophyll-b, and carotenoids. During the flowering phase, 100 mg of fresh leaf material was ground in 5 ml of 80% acetone using a mortar and pestle until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. The resulting mixture was filtered using filter paper. Subsequently, the resulting filtrate was adjusted to a volume of 10 ml with 80% acetone. The absorbance of leaf extract was measured at wavelengths: 663.2, 646.8, and 470 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (AE-UV 1606). 80% acetone served as a blank. The concentrations of photosynthetic pigments were determined using specific equations below and expressed in milligrams per gram of fresh plant tissue weight.

The relative water content (RWC) in leaves was measured following Martínez et al.33. The RWC was calculated using the following equation.

\({\text{RWC}}\left( \% \right) = \frac{{{\text{Fw}} - {\text{Dw}}}}{{{\text{Sw}} - {\text{Dw}}}} \times 100\)

FW = leaf fresh weight immediately after sampling. DW = leaf dry weight after oven-dried. SW = leaf-saturated weight after exposure to distilled water.

To measure the content of hydrogen peroxide and membrane lipid peroxidation (malondialdehyde), the methods described by Nag et al.34 and Heath and Packer35 were used. The stability of the cell membrane was assessed using the membrane electrolyte leakage (EL) method, as outlined by Dionisio-Sese and Tobita36. The EL was calculated using the following equation.

\({\text{EL}}\left( \% \right) = \frac{{{\text{C}}1}}{{{\text{C}}2}} \times 100\)

C1 = initial electrical conductivity. C2 = final electrical conductivity.

The concentration of malondialdehyde was determined based on the relationship described by Narwal et al.37 and expressed as micromoles per gram of fresh weight.

\(\:\text{M}\text{D}\text{A}\:\left(\text{m}\text{m}\text{o}\text{l}/\text{g}\:\text{F}\text{W}\right)=\:\frac{\text{A}532-\text{A}600}{\text{Ɛ}\text{d}\text{F}\text{W}}\:\)× V

A = absorption rate. Ɛ = extinction coefficient of malondialdehyde at 532 nm (155 mM− 1cm− 1). V = sample volume (L). FW = weight of fresh plant tissue in the sample (0.1 g). d = width of cut (cm).

Proline was extracted following the method of Bates et al.38. Briefly, 100 mg of fresh leaf was ground in 5 ml of 80% acetone using a mortar and pestle until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. The resulting mixture was filtered using a filter paper. The required reagents were prepared using serial dilution, and leaf extracts were transferred into a falcon tube. The samples underwent centrifugation, and a portion of extract was moved into a new falcon tube, followed by adding 2 ml ninhydrin acid and 2 ml glacial acetic acid, and vortexed thoroughly. Samples were then heated in water bath at 100 °C for 1 h, followed by 10 min incubation in ice bath. Finally, 4 ml toluene was added to the solution and vortexed for 20 s. Samples were left undisturbed for 15–20 min to allow complete separation of the two phases. The supernatant containing toluene and proline was utilized to quantify proline concentration. The optical density of the prepared extracts was measured at 520 nm for proline. Toluene was used as a blank.

To extract antioxidant enzymes from leaf tissue, protein extracts were prepared and subsequently guaiacol peroxidase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase activities were quantified according to the method described by Narwal et al.37.

When pods had turned brown, plants were harvested to determine seed yield. Pods were air-dried for one week. After separating the seeds from pods, seed weight was measured in gram per plant.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected, organized, and visualized in MS Excel. Utilizing SAS 9.4 software, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted for the data as a factorial experiment. The treatment medians were compared using Tukey’s post hoc test at a 5% significance level.

Results

Effects on photosynthetic pigments

The effects of water status and Zn on photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b), and carotenoids, were statistically significant (p < 0.01) (Table 2). In drought stressed plants with no treatment, the levels of chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b decreased by 47.7% and 41.4%, respectively (Fig. 2a, b). Increasing Zn concentrations up to 200 mg/L with ZnO-NPs increased photosynthetic pigments, but decreased with ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment. Under drought conditions, chlorophyll-a and chlorophyll-b contents at 200 mg Zn/L with ZnO-NPs treatment were 33.1% and 20.7% higher, respectively, compared to ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment (Fig. 2a, b). Additionally, the chlorophyll-b content at 100 mg Zn/L with ZnO-NPs treatment was significantly higher compared to ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment (Fig. 2b). In both non-drought and drought conditions, the lowest carotenoid levels were observed in plants treated with a foliar concentration of 200 mg Zn/L, which was however not significantly different from 100 mg Zn/L. The difference in carotenoid levels between drought and non-drought conditions at 100 and 200 mg Zn/L was lower than untreated control and 400 mg Zn/L treatment (Fig. 2c).

Photosynthetic pigments (a–c) in soybean affected by water status and Zn concentrations. Zn concentrations 0-200 mg Zn/L are for ZnO-NPs, and 400 mg Zn/L is for ZnSO4 used for comparison as conventional fertilizer. Bars with similar letter are not significantly different, according to Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent ± SD.

Effect on hydrogen peroxide, electrolyte leakage, and malondialdehyde

The levels of hydrogen peroxide, electrolyte leakage, and malondialdehyde were significantly influenced by both the water status and the Zn concentrations (p < 0.01; Table 2). Under both drought and non-drought conditions, the levels of hydrogen peroxide decreased with increasing concentrations up to 200 mg Zn/L with ZnO-NPs treatment, but increased with ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment (Fig. 3a). Plants under drought had increased levels of hydrogen peroxide, electrolyte leakage, and malondialdehyde in untreated control plants compared to non-drought condition. Under non-drought conditions, the levels of malondialdehyde and hydrogen peroxide at 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatment were 44% and 31% lower compared to ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment (Fig. 3a, c). Under non-drought conditions, the level of electrolyte leakage at 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatment was not significantly different from lower concentration treatments (Fig. 3b).

Hydrogen peroxide (a), electrolyte leakage (b) and malondialdehyde (c) in soybean affected by water status and zinc concentration. Zn concentrations 0-200 mg Zn/L are for ZnO-NPs, and 400 mg Zn/L is for ZnSO4 used for comparison as conventional fertilizer. Bars with similar letter are not significantly different, according to Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent ± SD.

Under drought conditions, the levels of hydrogen peroxide at 100 and 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatments were 15% and 30% lower than ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment (p < 0.05). However, the levels of malondialdehyde and electrolyte leakage at the concentration of 400 mg Zn/L ZnSO4 treatment were similar to 100 and 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatment (p > 0.05). Additionally, the levels of hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde at 400 mg Zn/L ZnSO4 treatment were 23.4% and 34.7% lower, respectively, compared to untreated control (p < 0.05; Fig. 3a–c).

Effect on antioxidant enzymes

The impact of water status and Zn concentrations on the antioxidant enzyme activities was statistically significant (p < 0.01), including their interaction with the activity of catalase and superoxide dismutase (p < 0.05; Table 3). In untreated plants, guaiacol peroxidase activity increased by 75.8% under drought compared to non-drought conditions (Fig. 4a). The highest guaiacol peroxidase activity was observed at 100 and 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatments under drought conditions, which differed significantly from ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment (Fig. 4a). Additionally, the activity of catalase enzyme increased in drought conditions up to 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatment but decreased with ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment (Fig. 4b). At 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatment, catalase and superoxide dismutase activities increased by 62.6% and 28.5%, respectively, under drought stress compared to non-drought conditions (Fig. 4b, c). Under non-drought conditions, catalase and superoxide dismutase activities with 100 and 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatments were similar to ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase at 100 and 200 mg Zn/L under both conditions (Fig. 4b, c).

Antioxidant enzymes (a–c) in soybean affected by water status and zinc concentration. Zn concentrations 0-200 mg Zn/L are for ZnO-NPs, and 400 mg Zn/L is for ZnSO4 used for comparison as conventional fertilizer. Bars with similar letter are not significantly different, according to Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent ± SD. POX: guaiacol peroxidase, CAT: catalase, SOD; superoxide dismutase.

The results of the study indicate that foliar application of 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs under water stress led to a minimal change in reactive oxidant levels, as well as reduced malondialdehyde content, compared to 400 mg Zn/L ZnSO4 treatment and control.

Effect on relative leaf water content and proline

The RWC and proline content in leaves were influenced by both the water status and Zn concentrations (Table 3). The statistical analysis showed that the interaction effect of water status and Zn concentration on proline content was significant (p = 0.0005). Under drought conditions, the RWC in untreated control decreased by 35.7% compared to non-drought conditions. However, the RWC increased by 47.2% and 57.1% with 100 and 200 mg Zn/L of ZnO-NPs treatments, respectively, compared to control (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, the RWC in plants sprayed with 50 and 100 mg Zn/L of ZnO-NPs treatments was similar to that of ZnSO4 (400 mg Zn/L) treatment. Under drought conditions, with 200 mg Zn/L of ZnO-NPs treatments, RWC was similar to 400 mg Zn/L of ZnSO4 in non-drought conditions (Fig. 5a).

Relative water content (a), proline content (b) and seed yield (c) in soybean affected by water status and zinc concentrations. Zn concentrations 0-200 mg Zn/L are for ZnO-NPs, and 400 mg Zn/L is for ZnSO4 used for comparison as conventional fertilizer. Bars with similar letter are not significantly different, according to Tukey’s post hoc test (p < 0.05). Error bars represent ± SD.

The proline content decreased with increasing Zn concentrations up to 200 mg Zn/L (Fig. 5b). Notably, the decline in proline content was more pronounced under drought relative to non-drought conditions with ZnO-NPs treatments. The proline content at 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatment was reduced by 37.1% and 36.8% compared to 400 mg Zn/L of ZnSO4under non-drought and drought conditions, respectively. Under non-drought conditions, the proline content at 100 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs was similar to 400 mg Zn/L with ZnSO4 treatment, but a decrease of 33.5% was observed for 100 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs treatments, compared to control. Under drought conditions, the proline content at 50 mg Zn/L with ZnO-NPs treatment was like that of 400 mg Zn/L with ZnSO4 treatment, and it was 23.9% lower than the control (Fig. 5b).

Seed yield

The ANOVA (Table 3) indicated that the seed yield was influenced by water status, Zn concentrations, and their interaction. Under non-drought conditions, foliar applications of ZnO-NPs led to a significant increase in seed yield in soybean (Fig. 5c). The highest seed yield was recorded at a concentration of 200 mg Zn/L ZnO-NPs, showing a 30% and 79% increase compared to ZnSO4 and the control, respectively (Fig. 5c). Under drought conditions, ZnO-NPs at 200 mg Zn/L resulted in a 26% and 39% increase in seed yield, compared to ZnSO4 and control, respectively. Seed yield at 400 mg Zn/L ZnSO4 treatment was not significantly different from untreated control and 50–100 mg Zn/L of ZnO-NPs. The use of ZnSO4 under non-drought conditions boosted soybean seed yield by 38% compared to control, while under drought conditions, there was no significant difference between ZnSO4 treatment and control (Fig. 5c).

Discussion

Climate change-associated drought poses significant risks to soybean growth and yield, affecting both the physiological processes of the plants and the broader agricultural economy39. The findings of this study indicated that increasing photosynthetic pigments with foliar ZnO-NPs (up to 200 mg Zn/L) would promote chloroplast performance and subsequently plant growth, a result consistent with Ghani et al.40. Improved chlorophyll activity in Zn-supplied plants might mitigate the need to increase carotenoids to support plant growth (Fig. 2c). Leopold et al.41 demonstrated that treatment with ZnO-NPs at 100 mg/L resulted in a 60.1% increase in chlorophyll-a and a 24.7% increase in chlorophyll-b in soybean compared to untreated control. Furthermore, Garcialopez et al.42 found that applying ZnO-NPs at 1000 mg/L led to increased chlorophyll content in Habanero peppers compared to ZnSO4 treatment. Drought can lead to a decrease in light-absorbing pigments and the photosynthetic apparatus, which play crucial roles in the Calvin cycle and ATP synthesis43. However, Zn can promote photosynthetic efficiency in plants via protein synthesis, chlorophyll synthesis, and enzyme activity20. More specifically, Zn may promote photosynthetic efficiency in plants under drought stress via stimulating carbonic anhydrase activity44 and regulating leaf stomata45.

In our study, foliar application of Zn-based fertilizers helped overcome drought stress via inhibition of lipid peroxidation in soybean. Increased photosynthetic pigments upon ZnO-NPs treatments (Fig. 2a–c) improved primary productivity under drought stress. At the same time, the decrease in reactive oxidants’ levels reflected the protective effects of ZnO-NPs treatment, promoting nutritional quality, stress tolerance, and plant growth in soybean. Zinc plays a crucial role in safeguarding and maintaining cell membrane integrity. It is also involved in protein synthesis, membrane functionality, cell elongation, and resistance to environmental pressures46; thus, identification of the appropriate Zn dose is crucial for the maintenance of homeostasis and cell membrane stability47. It is well established that higher hydrogen peroxide levels lead to excess oxidative stress, causing peroxidation of cellular lipids. Hence, the lower levels of hydrogen peroxide in plants treated with ZnO-NPs treatment compared to ZnSO4 indicated a balance between ROS production and the efficacy of the antioxidant system in soybean under drought stress, as previously reported by Ruiz-Torres et al.30. Similarly, Sun Luying et al.48 demonstrated that ZnO-NPs treatment at 100 mg/L, as opposed to ionic Zn suspension, led to reduced malondialdehyde and hydrogen peroxide levels in corn under both drought and non-drought conditions. Furthermore, the levels of hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde were higher under drought compared to non-drought conditions. Additionally, several studies have reported a decrease in malondialdehyde and hydrogen peroxide accumulation, as well as electrolyte leakage by Zn-NP treatments49,50,51.

The application of Zn micronutrient, particularly in the form of ZnO-NPs, has been reported to enhance plants’ antioxidant system, including carotenoids and enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and guaiacol peroxidase, leading to protection against reactive oxidants and drought damage. Singh et al.52 reported increased growth and biochemical parameters, such as sugar content and nitrate reductase activity, compared to those treated with bulk ZnO in S. lycopersicum, B. oleracea var. Capitata, and B. oleracea var. Botrytis. Moreover, the study revealed that ZnO-NPs stimulated the function of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, and guaiacol peroxidase, while also boosting the levels of photosynthetic pigments and protein content in such plants. Another study reported increased catalase activity upon ZnO-NPs treatments up to 500 mg/kg but decreased at 1000 mg/kg in Phytolacca americana52. Similar changes in the activity of antioxidant enzymes following exposure to ZnO-NPs have been reported earlier53,54,55. Salehi et al.31 found that foliar spraying of bulk Zn increased both catalase and peroxidase enzyme levels compared to control. However, applying ZnO-NPs at 0-2000 mg/L resulted in increased peroxidase activity compared to similar concentrations of ZnSO4.

Drought stress has negative effects on various physiological processes in plants, including a significant reduction in RWC. Studies have shown that RWC exhibits an inverse linear relationship with drought56. Imran Qani et al.57 reported that RWC decreased under drought conditions compared to non-drought conditions. However, when cucumber plants were subjected to drought-free conditions and treated with ZnO-NPs at a concentration of 100 mg/L, the RWC increased by 7.7% compared to control. Under drought conditions, RWC increased by 14.4% and 32.5% when treated with 25 mg/L and 100 mg/L of ZnO-NPs, respectively, compared to control. In the current study, we observed that plants treated with 200 mg Zn/L of ZnO-NPs exhibited the lowest amount of proline (Fig. 5b) and the highest amount of photosynthetic pigments (Fig. 2a, b). This, along with the changes in hydrogen peroxide production and electrolyte leakage, suggests that foliar applications of ZnO-NPs alleviated the adverse effects of drought in soybean. Additionally, there was a significant reduction in lipid peroxidation, further supporting this assumption. Therefore, it is concluded that the nitrogen metabolism involved in proline accumulation in soybean is much lower with ZnO-NPs treatments compared to ZnSO4 treatments. Furthermore, plants treated with ZnO-NPs had lower levels of proline and higher RWC % compared to control plants under drought conditions.

This study demonstrated that ZnSO4 treatment can only enhance seed yield under non-drought conditions. However, under drought stress, a significant portion of the plant’s photosynthetic resources may be utilized to produce osmolytes like proline to prevent ROS accumulation and maintenance of RWC, resulting in lower yield compared to control58. On the other hand, ZnO-NPs significantly increased primary productivity and seed production under non-drought conditions, and more importantly, under drought conditions by promoting the antioxidant system, requiring less energy to counteract the oxidants (Figs. 4a-c and 5b). This study suggested that the allocation of plant energy towards seed production was relatively higher in plants treated with ZnO-NPs compared to ZnSO4. Despite drought stress induced seed yield loss (with control), seed production significantly increased with foliar ZnO-NPs compared to ZnSO4 treatment or the control. This can be attributed to ZnO-NP-mediated stimulation of leaf chlorophyll (Fig. 2a, b), leading to increased photosynthesis and, consequently, higher seed yield in soybean39,59. The findings of Ponce-García et al.60 demonstrated optimal doses favoring N2 assimilation and yield were 25 mg/L for ZnO-NPs and 50 mg/L for ZnSO4, which increased yield by 15.5 and 13.7 g/plant, compared to control, respectively. Likewise, Dola et al.61 reported increased yield by 63.5% under drought and 23.6% under non-drought conditions upon foliar treatment with 200 mg/L ZnO-NPs compared to untreated control. Considering impending drought in semi-arid regions, adapting agricultural practices involving Zn-NPs to improve drought stress tolerance in crops will provide an alternative to promote sustainable farming systems.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated the benefit of foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles on the photosynthetic and antioxidant systems in soybean. Compared to the application of zinc sulfate fertilizer, which rely heavily on osmolytes, switching to zinc oxide nanoparticles will lead to superior performance and improved seed yield in soybean. Overall, ZnO-NPs could promote soybean tolerance to drought stress and enhance seed yield by increasing antioxidant activities, relative water content, and photosynthetic pigments while decreasing stress-related proline content. Foliar application of 200 mg Zn/L in the form of ZnO-NPs could serve as an effective drought stress management strategy while improving crop production in drought-impacted regions.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author(s) upon reasonable request.

References

Mataveli, L. R. V., Pohl, P., Mounicou, S., Arruda, M. A. Z. & Szpunar, J. A comparative study of element concentrations and binding in transgenic and non-transgenic soybean seeds. Metallomics 2, 800–805. https://doi.org/10.1039/C0MT00040J (2010).

Lee, K. et al. Quality characteristics and storage stability of low-fat tofu prepared with defatted soy flours treated by supercritical-CO2 and hexane. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 100, 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2018.10.073 (2019).

Kumar, P. et al. Meat analogues: Health promising sustainable meat substitutes. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 57, 923–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2014.939739 (2017).

Blair, R. Nutrition and Feeding of Organic Poultry (CAB International, Oxfordshire, England, 2018) ISBN: 978-1-84593-406-4.

Sakai, T. & Kogiso, M. Soy isoflavones and immunity. J. Med. Invest. 55, 167–173. https://doi.org/10.2152/jmi.55.167 (2008).

Kanchana, P., Santha, M. L. & Raja, K. D. A review on Glycine max (L.) Merr. World J. Pharm. Sci. 5, 356–371 (2015).

Wang, S. et al. Monitoring and assessing the 2012 drought in the Great Plains: analyzing satellite-retrieved solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence, drought indices, and gross primary production. Remote Sens. 8, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs8020061 (2016).

Kah, M., Tufenkji, N. & White, J. C. Nano-enabled strategies to enhance crop nutrition and protection. Nat. Nanotechnol 14, 532–540. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-019-0439-5 (2019).

Wijewardana, C., Reddy, K. R. & Bellaloui, N. Soybean seed physiology, quality, and chemical composition under soil moisture stress. Food Chem. 278, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.035 (2019).

Fischer, S., Hilger, T., Piepho, H. P., Jordan, I. & Cadisch, G. Do we need more drought for better nutrition? The effect of precipitation on nutrient concentration in east African food crops. Sci. Total Environ. 658, 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.181 (2019).

Farooq, M. et al. Drought stress in grain legumes during reproduction and grain filling. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/jac.12169 (2017).

Sehgal, A. et al. Effects of drought, heat and their interaction on the growth, yield and photosynthetic function of lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) genotypes varying in heat and drought sensitivity. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1776. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01776 (2017).

Rahbarian, R., Khavari-Nejad, R., Ganjeali, A., Bagheri, A. & Najafi, F. Drought stress effects on photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence and water relations in tolerant and susceptible chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) genotypes. Acta Biologica Cracov. Ser. Botânica 53(1). https://doi.org/10.2478/v10182-011-0007-2 (2011).

Wu, S., Hu, C., Tan, Q., Nie, Z. & Sun, X. Effects of molybdenum on water utilization, antioxidative defense system and osmotic-adjustment ability in winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) under drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 83, 365–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.08.022 (2014).

Ahmad, P. et al. Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) improves tolerance to arsenic (as) toxicity in Vicia faba through the modifications of biochemical attributes, antioxidants, ascorbate-glutathione cycle and glyoxalase cycle. Chemosphere 244, 125480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125480 (2020).

Kaya, C. et al. Melatonin-mediated nitric oxide improves tolerance to cadmium toxicity by reducing oxidative stress in wheat plants. Chemosphere 627638 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.026 (2019).

Jubany-Marí, T., Munné-Bosch, S. & Alegre, L. Redox regulation of water stress responses in field-grown plants. Role of hydrogen peroxide and ascorbate. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48(5), 351–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.01.021 (2010).

Ali, Q. & Ashraf, M. Induction of drought tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) due to exogenous application of trehalose: Growth, photosynthesis, water relations and oxidative defense mechanism. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 258–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-037X.2010.00463.x (2011).

Ali, Q. et al. Efficacy of Zn-Aspartate in comparison with ZnSO4 and L-Aspartate in amelioration of drought stress in maize by modulating antioxidant defence; Osmolyte accumulation and photosynthetic attributes. PLoS One 16(12), e0260662. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260662 (2021).

Kumar, S., Kumar, S. & Mohapatra, T. Interaction between macro-and micro-nutrients in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 665583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.665583 (2021).

Tsonev, T. & Cebola Lidon, F. J. Zinc in plants-an overview. Emirates J. Food Agric. 24, 322–333 (2012).

Barker, A. V. & Pilbeam, D. J. Handbook of Plant Nutrition 2nd edn, 773 (Boca Raton, CRC Press, 2105). https://doi.org/10.1201/b18458

Singh, S., Singh, V. & Layek, S. Influence of sulphur and zinc levels on growth, yield and quality of soybean (Glycine max L). Int. J. Plant. Soil. Sci. 18(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.9734/IJPSS/2017/35590 (2017).

Yang, K. Y. et al. Remodeling of root morphology by CuO and ZnO nanoparticles: Effects on drought tolerance for plants colonized by a beneficial pseudomonad. Botany 96, 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjb-2017-0124 (2018).

Dimkpa, C. O. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviate drought-induced alterations in sorghum performance, nutrient acquisition, and grain fortification. Sci. Total Environ., 926–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.392 (2019).

Vaghar, M. S., Sayfzadeh, S., Zakerin, H. R., Kobraee, S. & Valadabadi, S. A. Foliar application of iron, zinc, and manganese nano-chelates improves physiological indicators and soybean yield under water deficit stress. J. Plant Nutr. 43(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2020.1793180 (2020).

Rameshraddy, Pavithra, G. J., Rajashekar Reddy, B. H., Salimath, M., Geetha, K. N. & Shankar, A. G. Zinc oxide nano particles increases Zn uptake, translocation in rice with positive effect on growth, yield and moisture stress tolerance. Indian J. Plant. Physiol. 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40502-017-0303-2 (2017).

Yusefi-Tanha, E., Fallah, S., Rostamnejadi, A. & Pokhrel, L. R. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) as a novel nanofertilizer: influence on seed yield and antioxidant defense system in soil grown soybean (Glycine max cv. Kowsar). Sci. Total Environ. 738, 140240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140240 (2020).

Nekoukhou, M., Fallah, S., Pokhrel, L. R., Abbasi-Surki, A. & Rostamnejadi, A. Foliar co-application of zinc oxide and copper oxide nanoparticles promotes phytochemicals and essential oil production in dragonhead (Dracocephalum moldavica). Sci. Total Environ., 167519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.167519 (2024).

Ruiz-Torres, N. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate impact physiological parameters and boosts lipid peroxidation in soil grown coriander plants (Coriandrum sativum). Molecules, 26, 1998. (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26071998

Salehi, H. et al. Exogenous application of ZnO nanoparticles and ZnSO4 distinctly influence the metabolic response in Phaseolus vulgaris L. Sci. Total Environ., 146331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146331 (2021).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Buschmann, C. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: measurement and characterization by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Curr. Protocols Food Anal. Chem. 1(1), F431–F438 (2001).

Martínez, J. P., Silva, H., Ledent, J. F. & Pinto, M. Effect of drought stress on the osmotic adjustment, cell wall elasticity and cell volume of six cultivars of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L). Eur. J. Agron. 26(1), 30–38 (2007).

Nag, S., Saha, K. & Choudhuri, M. A. A rapid and sensitive assay method for measuring amine oxidase based on hydrogen peroxide–titanium complex formation. Plant Sci. 157(2), 157–113 (2000).

Heath, R. L. & Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplast. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophysic. 125, 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1 (1968).

Dionisio-Sese, M. L. & Tobita, S. Antioxidant responses of rice seedlings to salinity stress. Plant Sci. 135(1), 1–9 (1998).

Narwal, S. S., Bogatek, R., Zagdanska, B., Sampietro, D. & Vattuone, M. Plant Biochemistry (Studium Press Texas, 2009).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant. Soil. 39(1), 205–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00018060 (1973).

Seleiman, M. F. et al. Drought stress impacts on plants and different approaches to alleviate its adverse effects. Plants (Basel Switzerland). 10(2), 259. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10020259 (2021).

Ghani, M. I. et al. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles: An effective strategy to mitigate drought stress in cucumber seedling by modulating antioxidant defense system and osmolytes accumulation. Chemosphere 289, 133202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133202 (2022).

Leopold, L. F. et al. The effect of 100–200 nm ZnO and TiO. Nanopart. Vitro-grown soybean plants Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces, 112536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2022.112536 (2022).

Garcia-Lopez, J. I. et al. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and zinc sulfate boosts the content of bioactive plants compounds in habanero peppers. Plants 8, 254. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants8080254 (2019).

Farooq, M., Hussain, M., Wahid, A. & Siddique, K. H. M. Drought Stress in Plants: An Overview. Plant Responses to Drought Stress 1–33 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg) (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32653-0_1

Zabaleta, E., Martin, M. V. & Braun, H. P. A basal carbon concentrating mechanism in plants? Plant Sci. 187, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.02.001 (2012).

Hu, H. et al. Carbonic anhydrases are upstream regulators of CO. Nat. Cell. Biol. 12, 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2009 (2010).

Cakmak, I. Tansley Review 111 possible roles of zinc in protecting plant cells from damage by reactive oxygen species. New Phytol. 146, 185–205. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1469-8137.2000.00630.x (2000).

Upadhyaya, H. et al. Physiological impact of zinc nanoparticle germination of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seed. J. Plant. Sci. Phytopathol. 1, 062–070. https://doi.org/10.29328/journal.jpsp.1001008 (2017).

Sun, L. et al. Nano-ZnO-induced drought tolerance is associated with melatonin synthesis and metabolism in maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21030782 (2020).

Hussain, A. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alter the wheat physiological response and reduce the cadmium uptake by plants. Environ. Pollut. 1518–1526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.036 (2018).

Rizwan, M. et al. Zinc and iron oxide nanoparticles improved the plant growth and reduced the oxidative stress and cadmium concentration in wheat. Chemosphere 214, 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.09.120 (2019).

Venkatachalam, P. et al. Enhanced plant growth promoting role of phycomolecules coated zinc oxide nanoparticles with P supplementation in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 110, 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.09.004 (2017).

Singh, N. B. et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles as fertilizer for the germination, growth and metabolism of vegetable crops. J. Nanoengineering Nanomanuf. 3(4), 353–364. https://doi.org/10.1166/jnan.2013.1156 (2013).

Shi, Y. et al. Microorganism structure variation in urban soil microenvironment upon ZnO nanoparticles contamination. Chemosphere 273, 128565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128565 (2021).

Qian, H. et al. Comparison of the toxicity of silver nanoparticles and silver ions on the growth of terrestrial plant model Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Environ. Sci. 25, 1947–1955. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1001-0742(12)60301-5 (2013).

Zoufan, P., Baroonian, M. & Zargar, B. ZnO nanoparticles-induced oxidative stress in Chenopodium murale L, zn uptake, and accumulation under hydroponic culture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 11066–11078. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-07735-2 (2020).

Reddy, A. R., Chaitanya, K. V. & Vivekanandan, M. Drought-induced responses of photosynthesis and antioxidant metabolism in higher plants. J. Plant Physiol. 161, 1189–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2004.01.013 (2004).

Imran Ghani, M. et al. Foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles: an effective strategy to mitigate drought stress in cucumber seedling by modulating antioxidant defense system and osmolytes accumulation. Chemosphere 289, 133202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.133202 (2022).

Hayat, S. et al. Role of proline under changing environments: A review. Plant Signal. Behav. 7(11), 1456–1466. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.21949 (2012).

Yang, Y. et al. Novel target sites for soybean yield enhancement by photosynthesis. J. Plant Physiol. 268, 153580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2021.153580 (2022).

Ponce-García, C. O. et al. Efficiency of nanoparticle, sulfate, and zinc-chelate use on biomass, yield, and nitrogen assimilation in green beans. Agronomy 9, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy9030128 (2019).

Dola, D. & Mannan, M. Foliar application effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on growth, yield and drought tolerance of soybean. Bangladesh Agron. J. 25, 7382. https://doi.org/10.3329/baj.v25i2.65940 (2023).

Funding

This study was funded, in part, by Shahrekord University (Grant #96GRN1M731 to SF) and East Carolina University (Grant #111101 to LRP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shahin Shirvani-Naghani: Conceptualized and designed the study, Investigation, Data collection and analysis, Writing-original draft preparation. Sina Fallah: Conceptualized and designed the study, Project administration, Supervision, Writing-original draft, Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition. Lok Raj Pokhrel: Conceptualized and designed the study, Data analysis, Writing-review & editing, Funding acquisition, Project advisory committee. Ali Rostamnejadi: Formal analysis, Interpreted nanomaterial properties, Writing-review & editing, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shirvani-Naghani, S., Fallah, S., Pokhrel, L.R. et al. Drought stress mitigation and improved yield in Glycine max through foliar application of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Sci Rep 14, 27898 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78504-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78504-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of Foliar Treatment with Organic Acids and Inorganic Nutrients on Yield Retention and Secondary Metabolite Profiles under Heat Stress in Soybean

Journal of Plant Growth Regulation (2026)

-

Combined Application of Vermicompost and Zinc Nanoparticles Improves Tuber Quality, Soil Health, and Cadmium Tolerance in Potato

Potato Research (2026)

-

Investigating the effect of foliar spraying of zinc nanoparticles and biostimulants on modulating the effect of water deficit stress in sugar beet by using Integrated Biomarker Response Version 2

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Nanofertilizers: smart solutions for sustainable agriculture and the global water crisis

Planta (2025)

-

Hormesis in field-grown Glycine Max (L.) with Foliar-Treatment of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Observed in Aerial and Belowground Traits Under Drought Stress

Journal of Plant Growth Regulation (2025)