Abstract

A verifiable and regional level method for mapping crops cultivated under organic practices holds significant promise for certifying and ensuring the quality of farm products marketed as organic. The prevailing method for the identification of organic crops involves labor-intensive manual inspections, detailed record-keeping of crop stages, and certification. Hyperspectral remote sensing is an evolving general sensing technique for extracting crop information across various scales. High-resolution hyperspectral data theoretically can distinguish numerous crops unambiguously at various levels of detail. The aim of this study is to investigate the possibility of spectral discrimination of a few vegetable crops (brinjal (Solanum melongena) and red spinach (Amaranthus dubius)) grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices and assess the inclusion of numerous landscape-level co-occurring crop species in the discrimination analysis. We acquired high-resolution in situ hyperspectral measurements on the research farms of the College of Agriculture, Kerala Agricultural University, Thiruvananthapuram, India, in the 2022 crop-growing season. Methodologically, quantifying the spectral discrimination as the multi-crop classification problem, we applied 12 different machine learning algorithms to assess the spectral discrimination and evaluated their relative performance across the diverse range of the crops considered. The results reveal intricate patterns of spectral discrimination. Vegetable crops grown under both organic and conventional chemical inputs-based practices indicate a high level (accuracy: 85–95%) of spectral discrimination. The effectiveness of the discrimination observed is significantly influenced, with a reduction in the accuracy of discrimination by 10%, by choice of the machine learning model and the presence of several co-occurring crop species. We advocate for coordinated, multi-site, and multi-phenology-based crop discrimination studies to ensure the stability of observed discrimination across different spatial and temporal contexts. The findings indicate that, due to physiological and biochemical differences, organically cultivated crops exhibit distinct spectral features than conventionally cultivated crops, and with a suitable ML method, it is plausible to map crops over geographically extant areas using hyperspectral remote sensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organic agriculture is practiced in 188 countries, with at least 4.5 million farmers managing over 96 million hectares of agricultural land using organic methods1. There is a growing demand for organic agricultural products, particularly in vegetable cultivation, mostly due to the perception that organic food is healthier and environmentally friendly as it avoids the use of synthetic chemical fertilizers and pesticides2,3. The conventional approach of identifying farm produce grown using organic methods is documentation-oriented and generally involves a certification process4,5. Organic producers are required to undergo annual certification by corporate certifying agencies. As part of this, representatives of the certifying agencies undertake limited on-site examinations to verify the organic status of the stated fields. Notwithstanding these document-based procedures, consumers face several issues in tracing and verification, and there is a lack of spatially visualizable and independent data-based tools to help identify the location of organic products. From the farmers’ perspective, the certification process is very time-consuming, prohibitively expensive, and often requires long-term agreements with the certifying agencies. Thanks to the several unscientific and opaque methods adopted in the labelling process by many certifying agencies6,7, from the consumer perspective, the quality and authenticity of farm produce labelled organic are subjective and is fraught with the risk of consuming farm produce grown under conventional cultivation methods while paying a premium by the label of ‘organic’8. The major limitation is the lack of a functionally verifiable method for the detection and mapping of fields that grow crops under organic cultivation practices.

Multispectral remote sensing has accomplished mapping and monitoring of crops over large geographical areas. Multispectral imaging sensors mounted on drones and satellites have become standard data sources for addressing crop detection and mapping requirements for precision agriculture9,10,11. Visible (Vis), Near-Infrared (NIR), and Shortwave Infrared (SWIR) wavelengths each offer distinct insights into the properties of plants. Plants absorb blue and red light for photosynthesis within the visible spectrum (400–700 nm), reflecting green light, which imparts their coloration. The NIR (700–1300 nm) spectrum is predominantly reflected by plant cellular structures, serving as a robust measure of plant health, vitality, and foliar density. SWIR (1300–2500 nm) is responsive to water content and moisture levels in vegetation, facilitating the identification of plant stress, drought conditions, and structural alterations. These wavelength interactions provide accurate observation of plant physiology, growth, and environmental reactions. Hyperspectral remote sensing, which captures the full spectrum interaction of a surface object with electromagnetic radiation in hundreds of special bands with very narrow bandwidth, is emerging as the data of choice for the precision discrimination of different crops12,13. A host of studies have demonstrated the potential of hyperspectral remote sensing data for discriminating between crops, weeds from crops, and cultivars of a crop with various degrees of success13,14,15. In principle, crops with distinct spectral biophysical traits have distinguishable spectral reflecting properties and cause the respective spectral signatures to be distinct16.

Based on the premise that crops grown under organic practices have distinct functional and biophysical differentiations compared to the crops that are grown under conventional cultivation practices, it is, possible to spectrally differentiate crops grown under different agronomic practices13,17.3 attempted to discriminate maize grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices using Landsat-5 and WorldView-2 multispectral satellite imagery , considered only one crop and against a common background. However, for functionally relevant methodological advancement, the prospects of mapping crops grown under organic cultivation practices need to be assessed from the perspective of a heterogeneous agricultural landscape and ought to consider the existence of several other co-occurring crops. Further, the spectral discrimination between crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices needs to be evaluated at the individual plant level for further upscaling to the field level using airborne or satellite imagery.

The objective of this research is the quantitative spectral discrimination of a few common vegetable crops cultivated under organic and conventional practices and its consistency while considering the existence of several co-occurring vegetable crops grown under conventional practices. Hyperspectral reflectance measurements acquired over several vegetable crops on the experimental farms of the Kerala Agricultural University, Thiruvananthapuram, are quantitatively analyzed using various statistical and machine learning approaches for assessing the spectral discriminability of crops grown under organic and conventional practices.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: in Section 2, the study area, data collection criteria, instruments used, dataset description, data pre-processing, and the primary methodology are described. In Section. 3, experimental results and analysis are described. Section 4 presents a comprehensive discussion of the results and impacts of various ML classifiers, and Section 5 concludes the work with future scope.

Data and methodology

Spectral reflectance measurements

Kerala Agricultural University, India, established a center of excellence in organic farming to encourage and transform the regional landscapes from the prevailing conventional agricultural practices into organic ones. As part of the activities of promoting and producing quality organic crop inputs such as seeds, seedlings, organic fertilizers, pest and disease control agents, etc., numerous crops are routinely grown on the research farms of the College of Agriculture (CoA), Kerala Agricultural University, Thiruvananthapuram, India. The CoA has one of the largest certified organic research farming facilities in India, with crop-growing activities undertaken in multiple seasons throughout the year. For reference studies on the spectral distinctness of organic crops, we considered reflectance data acquisition on two types of crop growth experiments - (i) two crops, brinjal (Solanum melongena) and red spinach (Amaranthus dubius), grown under both the organic and conventional cultivation practices and (ii) crops grown under conventional cultivation practices. Seventeen different crops - vegetables, fruits, cereals, and spices belonging to nine different families of plants formed the crops sampled for measuring spectral reflectance. The list of crops and the cultivars used are detailed in Table 1. Except for banana (Musa acuminata) and chilli (Capsicum annuum), the crops were sown or transplanted in the winter season from 20 - 30 September 2022. Bananas and chili were planted in June and August 2022, respectively. The crops were cultivated based on the recommendations documented in the adhoc package of practices recommendations for organic farming18 and the package of practices recommendations: crops 201619. The agronomic practices related to providing nutrients and managing crop growth, such as pests, diseases, weeds, and contamination, were undertaken as prescribed in the aforementioned references. With a mean sea level of 15 meters, Thiruvananthapuram is a tropical climate region with an annual mean temperature of 25.7 °C. Predominantly from southwest monsoons, this region receives annual rainfall of about 2100 mm. Due to its favorable climatic and weather conditions, the region is suitable for growing various crops and up to three cropping seasons a year. The location map of the study site is shown in Fig. 1.

The spectral signatures were collected using two sets of hyperspectral spectroradiometer ((i) make: ASD, USA, Model: FieldSpec3; (ii) make: SVC, USA, model: HR1024i) to acquire the measurements under stable illumination conditions and with minimal temporal deviations. The ASD FieldSpec3 has a Full-Width-Half-Maximum (FWHM) of 3 nm at 700 nm, 10 nm at 1400 nm, and 10 nm at 2100 nm. The SVC HR1024i has 3.3 nm, 9.5 nm, and 6.5 nm, respectively. Both the instruments have a wavelength range that extends from 350 nm to 2500 nm and a field of view (FOV) of 25°. As per the phenological stage observed for different groups of the crops considered, spectral reflectance measurements were undertaken during 15–21 November 2022. The measurements were acquired on sunny days with clear skies between 11 and 1 pm. To ensure quality spectral measurement and minimize the influence of background reflectance, spectral measurements were recorded holding the optical tip of the sensor over the plant at a height varying between 5 and 25 cm depending upon the crop type and growth condition of the plant being sampled.

Multiple spectral reflectance samples were acquired for each crop based on the plant condition, intra-crop phenological variation, and spatial distribution. As an approximation of the measurement of solar irradiance required for calibration of the reflectance measurements, we acquired spectral measurements over a reference panel made of Barium Sulfate (BaSO4) at each measurement location and also adjusted according to the perceived changes in the illumination conditions. Filtered for outliers and extremities in the spectral variations, we obtained 536 spectral reflectance measurements for all the crops for further processing and analysis. The number of spectral reflectance measurements considered for each crop is listed in Table 2.

Pre-processing of spectra

The raw spectral measurements were converted from radiance to reflectance by normalization against the white reference panel. As the raw spectra were distorted and contained small spikes, the Savitzky-Golay smoothening algorithm was applied to smooth the spectra. To establish baseline spectral data processing, we performed spectrum normalization and wavelength resampling to a uniform spectral interval of 5 nm, as the spectral measurements were obtained using two distinct instruments. After accounting for removing spectral outliers and measurement extremities, we retained reflectance measurements in 369 spectral channels spread across the optical range of the electromagnetic spectrum. Fig. 2 shows the mean reflectance spectra of crops considered for the study.

Mean reflectance spectra of considered crops: (a) organic vs. conventionally cultivated crops, and (b) other considered crops; RS (Red spinach), BN (Banana), C (Cabbage), G (Ginger), GC (Green Chilli), BG (Bitter Gourd), BoG (Bottle Gourd), CF (Cauliflower), CB (Cluster Bean), CM (Cucumber), O (Okra), R (Rice), RG (Ridge Gourd), SG (Snake Gourd), T (Tomato), WB (Winged Beans).

To reduce the issue of high dimensionality of hyperspectral data, we applied the Principal Component Transformation (PCT). This process resulted in transforming the high dimensional reflectance data to a manageable dimension of 35 while retaining the gross spectral features of full dimensional data. The first three PCA components explained 80% of variances, and all 35 components explained nearly 99% of total variance. Fig. 3 shows the first three principal components in a 3-dimensional space of spectral reflectance data of the crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices.

Spectral discriminant analysis using statistical and machine learning approaches

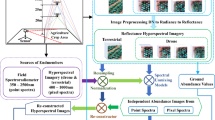

The methodological framework employed to discriminate various crop spectral signatures using statistical and machine learning algorithms is depicted in Fig. 4.

Two crops; - brinjal and red spinach, were cultivated under both organic and conventional agricultural practices. In contrast to the statistical separability approach utilized in previous studies, our evaluation of crop discrimination was conducted from a functional perspective. Specifically, we view it as a classification task where the quality of spectral discrimination is directly linked to classification accuracy. Moreover, a method selected for classification significantly impacts the accuracy of the results. Consequently, twelve distinct statistical and machine learning (ML) algorithms were employed for classification. We provide a brief description of the algorithms and the heuristics of tuning parameters for quick reference. Since these algorithms are widely reported, we recommend referring to the references cited for more details.

Logistic regression20,21 is a statistical modeling technique used for classification. A multiclass classification problem uses the one vs. rest (OvR) technique in which one by one class is targeted as a positive class, and the rest of the classes, as combined, are treated as a negative class. We used the ‘L2’ penalty because the resulting model is not sparing, and all the coefficients are reduced with the same factor. The utilized loss function for this algorithm can be expressed using Eq. (1):

where (x, y) \(\in\) D is the spectral reflectance dataset, y is the actual labels of the crop classes, and y’ is the predictions by the trained logistic regression model.

Ridge classifier22 applied to the crop spectral reflectance dataset converts all the class labels to be within the range of -1, +1 and then solves the crop discrimination problem as a regression task. The regularization strength (alpha) values are 1.0 for this problem. ‘L2’ penalty is added to the loss function in ridge classification, which can be seen in Eq. (2):

where \(\lambda\) is the regularization parameter used for large coefficient values, w is the parameters vector, c is the intercept, and (x, y) belongs to the utilized dataset, x is the feature vector, and y is the class label.

Stochastic gradient descent (SGD)23 classifier implements the regularized linear model with SGD optimization. The loss gradient is calculated for every spectral reflectance sample at a time and updated in the model. It allows small batch learning, and convex loss function ‘hinge’ loss is used, expressed in expression (3):

where \(y_i\) is the actual label and f(\(x_i\)) is the output label function.

K-nearest neighbor (KNN)24 is the simple but elegant classification algorithm in which a classification decision is based on the nearest neighbor value ‘k.’ A targeted data point measures Euclidean distance, and the point is classified based on the majority voting. The value of ‘k’ can only be an odd positive number. The Euclidean distance can be calculated using the below-given formula in Eq. (4):

where \(v_1\)= (\(x_1\),\(x_2\),\(x_3\ldots x_d\)) and \(v_2\)= (\(y_1\),\(y_2\),\(y_3\ldots y_d\)) are the feature vectors, and M is the feature space dimensionality.

Decision tree classifier25 is a supervised, non-parametric algorithm to solve a classification problem. It uses different algorithms to decide on splitting the nodes’ hierarchy. We used the ‘Gini’ algorithm for this crop discrimination problem. Gini impurity can be calculated based on Eq. (5):

where \(p_i\) is the probability of picking a data point from utilized spectral dataset classes, and n is the total number of classes.

Support vector machine (SVM)34 is one of the most sophisticated classifiers used for classification purposes. SVM tries to draw a hyperplane between the classes and maximize the margins. Primarily, SVM is a binary classifier using multiple SVM machines; it can also be applied to multiclass problems. We used a linear kernel for our crop spectral reflectance discrimination problem. Equation (6) gives the hyperplane equation:

where W is the average vector to the hyperplane, x is the input data vector, and d is the intersection of the hyperplane from the origin.

Crop spectral reflectance data can be non-linearly separable, SVM with radial basis function (RBF) kernel can be used. RBF tries to find the similarity between two points, \(p_1\) and \(p_2\). Equation (7) can represent the RBF kernel:

where \(\sigma\) is the variance, \(||p_1-p_2 ||\) is the Euclidean distance between the points \(p_1\) and \(p_2\).

Gaussian naïve Bayes26 algorithm primarily works based on the Bayes theorem and supposes that each class in the crop spectral reflectance dataset follows the normal distribution. The Gaussian NB considers features independent of each other; hence, the covariance matrix will be diagonal. The Gaussian’s naïve Bayes theorem can be expressed as the following Eq. (8):

where \(P(x_i|y=c)\) is the posterior probability for a class c, d is the dimension of \(x, \sigma _c\) is the covariance matrix, \(\mu _c\) Is the mean for a class c.

Adaboost24,27 is an adaptive ensemble learning algorithm that combines many weak classifiers to form a robust classifier and tweaks the weak classifiers to perform best based on previous iterations. Adaboost gives more weight to minor discriminative instances and more weight to easily discriminatory examples. In general, a boosted classifier can be expressed as shown in Eq. (9):

where x is an object given as an input in weak learner \(f_k\) and returns the output as an object of the class, and K is the total number of classifiers in the boosting algorithm.

Random forest28 is an ensemble learning technique combining multiple decision trees for classification. The crop spectral reflectance dataset is classified based on the majority voting for a particular class. We considered 100 decision trees as estimators. Variable importance is measured by the dataset \(D = [{(X_i, Y_i)}]_(i=1)^n\) before fitting it with random forest decision trees.

Gradient boosting29 algorithm is also an ensemble learning technique used for supervised classification. It includes decision trees as weak learners. Combined, it uses several weak learners and makes a single strong learner iteratively. It tries to minimize the mean squared error as given in Eq. (10):

where n is the number of training samples in the reflectance spectral dataset, \(\hat{y}\) are the predicted values of the function \(\hat{y} = F(x), y_i\) is the actual class label value.

Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (QDA)30 is a generative classifier that presupposes data following the normal distribution. QDA is suitable for datasets in which classes are not linearly discriminative. The discriminative boundary is non-linear in the case of QDA. The covariance matrix is not the same for each category in the case of QDA. The discriminative function of QDA can be expressed as given in Eq. (11):

where \(\Sigma _{n}\) is the covariance matrix, which is different for every class, \(\mu _n\) is the mean of a class.

Validation

We evaluated the performance of the discriminant analysis by the stratified five-fold cross-validation method with a 7:3 training and validation split ratio. While splitting the dataset, the shuffle was on, and the random state was initialized with 11 for each fold’s iteration. Hyperparameters were fixed before the training for all models. We assessed the models’ performance utilizing several widely referred non-parametric validation metrics. These metrics provide valuable insights into various aspects of the discrimination performance, such as Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1 score, Mean Squared Error, Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC), and Area Under the curve (AUC)31. Using this rigorous evaluation framework, we validated the reliability and robustness of the results. All the analysis is performed using Python and the Sklearn library.

Accuracy, precision, recall, F1 score, and mean squared error are essential metrics used to evaluate the performance of classification models, particularly in the context of imbalanced data sets such as crop labelling tasks. Accuracy represents the proportion of correctly predicted crop labels out of the total labels, providing a general measure of overall correctness. Precision for a specific crop class measures the ratio of correctly predicted labels for that class to the total predicted labels for that class, highlighting the model’s ability to avoid false positives. Recall for a particular crop class indicates the ratio of correctly predicted labels for that class to the total correct and incorrect labels for that class, showcasing the model’s ability to identify all relevant instances of that class. The F1 score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a balanced measure of a model’s performance, especially in imbalanced datasets where the classes have unequal distributions. It helps in determining the classification quality, considering both false positives and false negatives. The mean squared error measures the average squared difference between predicted and actual labels, which helps to assess the trained model’s quality. In contrast with these numerical description-based validation metrics, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a graphical representation that illustrates the performance of a crop classification model across various thresholds. It provides valuable insights into the trade-off between the true positive rate (TPR) and the false positive rate (FPR) at different threshold values. The area under the ROC curve (AUC-ROC) is a commonly used metric to quantify the overall performance of a classification model. A higher AUC-ROC value indicates better discrimination capability, with a value of 1 indicating perfect classification and a value of 0.5 indicating random classification.

Results and analysis

Organic farming generally exhibits more reflectance in the visible spectrum (400–700 nm) owing to elevated chlorophyll content, signifying superior plant pigmentation compared to conventionally produced crops, which may possess reduced chlorophyll levels as a result of chemical stress or nutrient inadequacies. In the NIR region (700–1300 nm), organic crops demonstrate superior biomass and leaf architecture, resulting in increased reflectivity, as NIR is responsive to plant vitality and cellular composition. Conventional crops frequently exhibit diminished NIR reflectance attributable to compromised plant health or stress induced by synthetic inputs. Organic crops exhibit enhanced moisture and nutrient retention in the SWIR band (1300–2500 nm), leading to increased reflectance. Conversely, conventionally cultivated crops may demonstrate reduced moisture content and possible chemical residues, indicating their dependence on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, which can affect plant health and water retention. The results of the spectral discrimination crops grown under conventional and organic cultivation practices are presented and analyzed in the following sub-sections. As the methodological implementations considered two distinct but related cases of spectral analysis, we describe the results in two cases of analysis: (i) the spectral discrimination of the crops grown under both the organic and conventional cultivation practices and (ii) assessing the spectral discrimination of crops grown under organic cultivation practices against the numerous crops co-occurring in the same agro-ecological region.

Case I: spectral discrimination between crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices

The results of the spectral discrimination analysis for the crops grown under both organic and conventional practices are summarized in Table 3. The results suggest that the crops (e.g., brinjal, red spinach) grown organically can very well be differentiated from their counterparts-the same crops grown under conventional practices. Most machine learning approaches offered reasonably good accuracy in discriminating crops grown under organic cultivation practices. The consistent performance of the discrimination apparent across the different validation metrics suggests that spectral discrimination of organic and their respective conventional practices is stable and that there exist functionally relevant distinct spectral features of crops grown under organic practices. However, the accuracy varied moderately with the discrimination method used (see Table 3). There was about a 12% change in the accuracy when different methods were used.

Notwithstanding the apparent inter-method differences in discrimination performance, there is a minimum of 85% accuracy that can be attributed to the discrimination of the crops grown under organic practices. This observation suggests that organic crops can be functionally different, and the spectral features of the crops are sufficiently distinct, enabling quantitative differentiation of the organic crops against the features of the same crops grown under conventional cultivation practices. The change in the accuracy of spectral discrimination as a function of the rate of false positives is illustrated in Fig. 5. With a false positive rate of up to 20%, the quality of spectral discrimination is about 85% for each crop considered. The relatively stable pattern of the curve representing the micro-average (Fig. 5) indicates fairly good accuracy across the crops considered in this case.

Case II: spectral discrimination of organic crops against several co-occurring crops in the same agro-ecological region

The relatively high accuracy observed with the discrimination of the crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation (case I) is reflective of a semi-controlled farm growing in the sense that the experimental setup has not considered the presence of other crops in the landscape growing these crops. However, in real-world scenarios, particularly in heterogeneous and complex agricultural landscapes of Asia and Africa, organic crops are typically grown alongside an array of crops cultivated under conventional cultivation practices. To understand the potential field-level relevance of the spectral discrimination results, the spectral discrimination experiment should consider the presence of various co-occurring crop types within the broader agricultural landscape and assess the stability of the performances observed. Furthering this perspective, the results of the spectral discrimination of the organic crops considered against as many as 17 co-occurring crops are summarised in Table 4 and Fig. 6. Although the quality of discrimination is relatively inferior compared to case I, and the minimum accuracy observed across the different ML algorithms is as low as 24%, the accuracy estimates of multiple ML algorithms are fairly high and vary between 76% and 90%. This indicates that the apparent spectral discrimination of the crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices is systematic and spectrally distinct across the agroecological region. However, the accuracy of discrimination of these crops varies substantially, depending on the ML method used. Certain ML methods, e.g. Random Forests, particularly for crops that are more leafy, have shown higher performance. In this scenario, the stability of spectral discrimination is highly dynamic, and only certain sets of algorithms consistently offer higher accuracy, with very marginal differences among the algorithms.

The variation of the accuracy of discrimination as a function of the rate of false positives is illustrated in the ROC curve for the relatively better-performing ML method, Random Forests. The apparent closeness of the micro and macro average curves in the ROC plot, representing accuracy of 0.95 and 0.94, respectively, confirm the functional stability of the spectral features against the false positives. Statistical assessment of the validity and significance of the hypothesis (Ho: that crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices are not differentiable spectrally), for the best performing ML method (Random forests) was carried out. The results, assessed using paired t-test, suggest rejecting the null hypothesis with a p-value of 0.033 and t-statistics of 2.910.

Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) illustrating the variation of the accuracy at different levels of false positives for the spectra discrimination of organic crops against several co-occurring crop types Legend: WB (winged beans), T (tomato), SG (snake gourd), RG (gidge gourd), RS (red spinach), R (rice), GC (green chilli), G (ginger), C (cabbage), B (brinjal), BN (banana), O (okra), CM (cucumber), CB (cluster bean), CF (cauliflower), BoG (bottle gourd), BG (bitter gourd).

Discussion

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) has been widely used for the discrimination of various types of crops13,15. Remote sensing-based identification of crops grown under organic cultivation practices has vital applications in agriculture, industry, and public health. Even though HSI technology is being applied intensively in various areas of precision agriculture (e.g. mapping of crops at cultivar level), its utility for discriminating crops under distinct agronomic management strategies, e.g.organic versus conventional practices, has only been felt somewhat recently. Other than the work of3, which attempted mapping of organic maize using Landsat-5 and WorldView-2 multispectral imagery, there have been few studies17,32,33 that have assessed the spectral discrimination of crops grown under organic and conventional practices and the stability of the spectral discrimination when considering several co-occurring species. We have assessed the potential of the spectral discrimination of crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices using in situ hyperspectral measurements acquired on the fields during an experimental session. The discrimination quantified using multiple machine learning and statistical techniques (mentioned in Tables 3, 4) suggests that organic crops can be discriminated against their respective conventional crops.

In addition to the existing practices, the results also suggest that spectral discrimination is substantially influenced by the methods used. As evident from the results presented in case I, most of the ML methods performed similar in differentiating organic crops from their respective conventional crop cultivation practices and offered a high level of accuracy. However, when spectral discrimination is assessed against numerous co-occurring crop species in the landscape, the quality of spectral discrimination of organic crops has decreased substantially. However, this performance loss is method-specific, and there are a few ML methods that produce results with fairly high accuracy (e.g., the Random Forests algorithm offered about 90% accuracy). This observation suggests the continuity of spectral distinctness of organic crops at the landscape level. Most ensemble algorithms used have offered classification performances ranging from 24% to 90%, which is substantially lower compared to the case of only organic versus conventional crops. This is explainable: as the number of crops increases, the complexity of spectral variation increases, and the contribution background reflectance is enhanced, thereby increasing the diversity of spectral signatures of crops and hence reducing the uniqueness of spectral features that might have contributed otherwise.

Knowing the possibility of spectral discrimination and contrast among the crop species regarding the co-occurring crop species is vital. It is also crucial to explore the potential of multi-platform hyperspectral remote sensing for crop discrimination at the field level, especially the prospect of differentiating the vegetable crops grown under organic growing practices. It has crucial applications in ensuring the quality, authenticity, and safety of cultivated vegetables. As an attempt to add this vital research area, this study has evaluated, from proof-of-concept (PoC), the ability to distinguish between up to 17 crops that grow together in agricultural environments and has investigated the possibility of using hyperspectral remote sensing to differentiate between organic vegetable crops and those that have been treated with chemicals based conventional cultivation practices.

This study has considered a limited number of organic crops, which are mainly vegetable, though the co-occurring crops are composed of variety of crops; fruit-yielding vegetables, leafy vegetables, tubers, and gain-yielding. However number of crop samples in the dataset are limited, but they provides valuable insights, its size may present challenges in drawing definitive conclusions. Nonetheless, ongoing growth and improvement of the data can augment its usefulness and yield more comprehensive conclusions. In addition, reference spectral signatures were acquired at a limited time period, though at a spectrally responsive phenological stage. While under these experimental limitations, the results enabled us to attempt the broad research question of spectral differentiation of crops grown under organic and conventional practices, expansion of experiments over multiple landscapes and enhanced variety of crop types will help understand the specifics of spectral capabilities of HSI in this distinct precision agriculture application.

The reference spectral signatures acquired in this study (which are accessible for interested researchers upon request) serve as valuable data for agricultural research and development projects aimed at improving crop production and sustainability. By integrating spectral data with other sources of information, such as weather data, soil data, and crop models, researchers can gain deeper insights into the complex interactions shaping crop performance and develop innovative solutions to enhance agricultural resilience and productivity. Spectral discrimination of organic versus conventional crops is limited by factors like cost, data complexity, and environmental variability. Future applications involve crop monitoring, precision agriculture, and real-time quality evaluation to improve cultivation practices, farming methods, and food traceability and authenticity.

Conclusions

In a first of its kind, this study has investigated the possibility of hyperspectral differentiation of vegetable crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices, and its relative performance against the inclusion of numerous co-occurring crop species grown in the same landscape. Spectral discrimination assessment, quantified by the classification performance of several ML algorithms, suggests a consistently higher level of differentiating vegetable crops grown under both organic and conventional cultivation practices. The level of discrimination decreased substantially (about 10%) when the organic crops were discriminated against several (17) co-occurring crop species. The findings indicate the possibility of using hyperspectral data to map the geographical distribution of crops cultivated under organic farming. Despite the spectral similarity apparent for some crop species, the observation of simultaneous differentiation of numerous crops with a fair level of accuracy is significant from the perspective—choosing an appropriate ML method, HSI can be a viable technique for mapping crops grown under organic practices. We recommend further studies expanding the scope of the work to multiple sites and using satellite hyperspectral imagery.

Data availability

The datasets generated in this study are accessible through the corresponding author and can be provided to interested researchers upon request (rao@iist.ac.in).

References

Willer, H., Trávníček, J. & Schlatter S. The World of Organic Agriculture. Statistics and Emerging Trends 2024. Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL and IFOAM-Organics International.

Prache, S. et al. Review: Quality and authentication of organic animal products in Europe. Animal. 16, 100405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.animal.2021.100405 (2022).

Denis, A. et al. Multispectral remote sensing as a tool to support organic crop certification: Assessment of the discrimination level between organic and conventional maize. Remote Sens. 13(1), 117 (2020).

Cavallet, L. E., Canavari, M. & Fortes, P. Participatory guarantee system, equivalence and quality control in a comparative study on organic certifications systems in Europe and Brazil. Revista Ambiente & Água. 13(4), e2213 (2018).

Brito, T. P., de Souza-Esquerdo, V. F. & Borsatto, R. S. State of the art on research about organic certification: A systematic literature review. Organic Agric. 12(2), 177–190 (2022).

Morath, S.J. Regulating Organic. https://aulawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Morath.to_.Printer.pdf.

Lozano-Castellón, J. et al. Proven traceability strategies using chemometrics for organic food authenticity. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 147, 104430 (2024).

Busch, M., Mühlrath, D. & Herzig, C. Fairness and trust in organic food supply chains. British Food J. 126(2), 864–878 (2024).

Lu, T., Gao, M. & Wang, L. Crop classification in high-resolution remote sensing images based on multi-scale feature fusion semantic segmentation model. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1196634 (2023).

Deng, H., Zhang, W., Zheng, X. & Zhang, H. Crop classification combining object-oriented method and random forest model using unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) multispectral image. Agriculture. 14(4), 548 (2024).

Allu, A. R. & Mesapam, S. Fusion of different multispectral band combinations of sentinel-2A with UAV imagery for crop classification. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 18(1), 016511–016511 (2024).

Agilandeeswari, L., Prabukumar, M., Radhesyam, V., Phaneendra, K. L. N. B. & Farhan, A. Crop classification for agricultural applications in hyperspectral remote sensing images. Appl. Sci. 12(3), 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12031670 (2022).

Shunshi, H., Bin, Y., Ying, H., Yi, C. & Wenchao, Q. Fine classification of vegetable crops covered with different planting facilities using UAV hyperspectral image. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 28(1), 280–292 (2024).

Patel, U., Pathan, M., Kathiria, P. & Patel, V. Crop type classification with hyperspectral images using deep learning: a transfer learning approach. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 9(2), 1977–1987 (2023).

Ali, I. et al. Hyperspectral images-based crop classification scheme for agricultural remote sensing. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 46(1), 303–319 (2023).

Miller, H. I. Buying ‘organic’ to get ‘authenticity’? or safer and more nutritious food? Think again and again. Missouri Med. 116(1), 8 (2019).

Atanasova, D., Bozhanova, V., Biserkov, V. & Maneva, V. Distinguishing areas of organic, biodynamic and conventional farming by means of multispectral images. A pilot study. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 35(1), 977–993 (2021).

Alexander, D., Rajan, S., Rajamony, L., Ushakumari, K. & Kurien, S. The adhoc Package of Practices recommendations for organic farming. https://keralaagriculture.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/package_2015.pdf.

Estelitta, S. Package of practices recommendations: crops 2016. Kerala Agricultural University. https://kau.in/sites/default/files/documents/pop2016.pdf.

Homser, D. W. & Lemeshow, S. Applied logistic regression (Wiley, New York, 1989).

McCullagh, P. Generalized linear models (Routledge, London, 2019).

Grüning, M. & Kropf, S. A ridge classification method for high-dimensional observations. In From Data and Information Analysis to Knowledge Engineering: Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the Gesellschaft für Klassifikation eV University of Magdeburg, March 9–11, 2005. Springer; p. 684–691. (2006).

Bottou, L. Large-scale machine learning with stochastic gradient descent. In Proceedings of COMPSTAT’2010: 19th International Conference on Computational StatisticsParis France, August 22-27, 2010 Keynote, Invited and Contributed Papers. Springer; p. 177–186. (2010).

Hastie, T., Rosset, S., Zhu, J. & Zou, H. Multi-class adaboost. Statistics and its Interface. 2(3), 349–360 (2009).

Kotsiantis, S. B. et al. Supervised machine learning: A review of classification techniques. Emerging artificial intelligence applications in computer engineering. 160(1), 3–24 (2007).

Zhang, H. The optimality of naive Bayes. https://www.cs.unb.ca/~hzhang/publications/FLAIRS04ZhangH.pdf.

Freund, Y. & Schapire, R. E. A short introduction to boosting. J. Jpn. So. Artif. Intell. 14(5), 771–780 (1999).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Springer. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1023/a:1010933404324.pdf.

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Wu, W. et al. Comparison of regularized discriminant analysis linear discriminant analysis and quadratic discriminant analysis applied to NIR data. Anal. Chimica Acta. 329(3), 257–265 (1996).

Joshi, R. C., Kaushik, M., Dutta, M. K., Srivastava, A. & Choudhary, N. VirLeafNet: automatic analysis and viral disease diagnosis using deep-learning in Vigna mungo plant. Ecol. Inform. 61, 101197 (2021).

Eskandari, I., Navid, H. & Rangzan, K. Evaluating spectral indices for determining conservation and conventional tillage systems in a vetch-wheat rotation. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 4(2), 93–98 (2016).

Xiao, R., Liu, L., Zhang, D., Ma, Y. & Ngadi, M. O. Discrimination of organic and conventional rice by chemometric analysis of NIR spectra: A pilot study. J. Food Measur. Character. 13, 238–249 (2019).

Cortes, C. & Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 20, 273–297 (1995).

Funding

This study is part of doctoral research and has not received any third-party funding other than the fellowship given to the lead author by the Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology, Thiruvananthapuram, Government of India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRediT: Conceptualization: Rama Rao Nidamanuri, Aparna; Methodology: Manoj Kaushik; Implementation and coding: Manoj Kaushik; Formal analysis and investigation: Rama Rao Nidamanuri, Manoj Kaushik; Writing: Original draft preparation: Manoj Kaushik;Writing: Review and editing: Rama Rao Nidamanuri, Aparna; Supervision: Rama Rao Nidamanuri

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning this article’s research, authorship, or publication.

Ethical approval

This study has not used data or samples pertaining to any humans or animals. No ethical committee approval is required for this study as such. This study used data on cultivated plants, including vegetable crops such as Brinjal and Red spinach. We would like to declare that the study has complied with all the relevant guidelines applicable, and the permissions required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kaushik, M., Nidamanuri, R.R. & Aparna, B. Hyperspectral discrimination of vegetable crops grown under organic and conventional cultivation practices: a machine learning approach. Sci Rep 15, 7897 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78714-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78714-7