Abstract

In this study, sufaid chonsa mango pulp aqueous extracts from different ripening stages (RS I-V) was utilized to synthesize silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs). The Ag NPs were characterized using UV-vis spectrometry, X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), and Energy dispersice X-ray analysis (EDX). Additionally, antioxidative potential and phenolic and flavonoid-like properties of synthesized Ag NPs were also accessed. UV-vis spectrophotometer analysis showed peaks in around 400 nm. XRD analysis confirmed the crystalline structure of the green-synthesized Ag NPs, with sizes ranging from 2.11 to 11.72 nm. FTIR verified the attachment of functional groups from the mango pulp extract to the Ag NPs. SEM analyses revealed that the morphology of the Ag NPs was primarily spherical that were agglomerated. The total antioxidant capacity, measured by the DPPH assay, showed 51% radical scavenging activity for RSIII extract synthesized NPs. The highest total antioxidant capacity was observed to be 80.22 and 79.14 µg AAE/mg NPs by RSI and RSIV synthesized NPs, respectively, while the maximum total reduction potential was 28.67 µg AAE/mg for Ag NPs synthesized by RSII extract. Ag NPs derived from RSIV exhibited phenolic-like property of 70.84 µg GAE/mg, while those derived from RSII had a maximum flavonoid-like property of 35.37 µg QE/mg. This study demonstrates that mango pulp at different ripening stages produces Ag NPs with distinct characteristics, making them suitable for various environmental and biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mango, “the king of fruits” is not only delicious but also packed with numerous health benefits. Mangoes are rich in vitamins, folate, polyphenols, antioxidants, including quercetin, beta-carotene, astragalin, and also have fibers1,2. These compounds help to protect the body against oxidative stress, inflammation, reducing the risk of chronic diseases, boost the immune system, aids in digestion, and have anticancer properties3,4,5. However the concentrations of biomolecules vary during the maturity and ripening stages.

The synthesis of silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) using green chemistry principle has garnered significant attention due to its eco-friendly and sustainable approach. Green synthesis methods typically utilize plant extracts, microorganisms, or other biological systems as reducing and stabilizing agents, avoiding the use of harmful chemicals6,7. The use of plant extracts is one of the most common green methods for synthesizing Ag NPs. Plants contain various phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols, which act as reducing, stabilizing, and capping agents. As noted by Mittal et al.8, these methods align with the principles of green chemistry by reducing environmental impact and enhancing safety. Ag NPs synthesized through green methods are often biocompatible, making them suitable for medical and pharmaceutical applications. These methods can also be easily scaled up for large-scale production without significant environmental hazards9. Utilizing natural resources like plant extracts can reduce the overall cost of nanoparticle synthesis. Ag NPs exhibit strong antimicrobial properties and are used in coatings, textiles, and medical devices to prevent infections. Due to their unique properties, Ag NPs are being explored for targeted drug delivery and photothermal therapy in cancer treatment10,11,12.

Mango peel and leaves contain diversity of phytochemicals therefore have been explored for synthesis of many metallic and metallic oxide nanoparticles13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Shamim & Maz and Yahya et al. reported synthesis of nanoparticles using mango pulp. Due to collective effect of metal and stabilizing/capping molecules, these NPs have shown antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant, and many other activities3,22.

Mango ripening is a complex physiological and biochemical process that transforms the fruit from an inedible, hard, and sour state to a sweet, aromatic, and soft one. This process involves various changes in the fruit texture, color, flavor, and nutritional composition. A number of biochemical and phytochemical changes occur during the ripening starting from ethylene production to breakdown of carbohydrates, production of carotenoids, and change in concentration of polyphenols, vitamins, and organic acids. The synthesis of various volatile compounds, including esters, aldehydes, and alcohols also influence phytochemical divergence in mango pulp23,24,25,26.

Keeping in view phytochemical change during the mango ripening process, this work was designed to synthesize silver nanoparticles using sufaid chonsa mango pulp extract collected at different ripening stages (RS I - RS V). The NPs were synthesized using standard protocol, characterized by UV-vis, FTIR, XRD, EDX, and SEM. Furthermore the synthesized NPs were also accessed for antioxidative response to determine biocompatibility.

Materials and methods

Materials

All the chemical were purchased from Merck Germany otherwise mentioned. The mango cultivar sufaid chonsa was collected from Multan region Punjab Pakistan. The fruit was collected from the tree verified by the Taxonomist Department of Botany GC Women University Sialkot and a voucher specimen (TL-856/24) was deposited in herbarium.

Collection and processing of mango

Green mature mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruits of uniform size (average weight of 100–150 g) of the sufaid chonsa cultivar were harvested from a field of Multan Punjab Pakistan and transported to the laboratory for evaluation. The fruits were sanitized with chlorinated water for 3 min and left to dry at room temperature (23–26 °C) for about 1 h. For this study, fifteen mangoes were separated. The ripening process was carried out under commercial conditions rather than strict physiological conditions. The fruits were packed in cardboard boxes with holes, and approximately 0.5 g of calcium carbide in a paper bag was placed in the center of the box. The mangos were physically observed for hardness, color and smell at 24 h interval till the maturity/ripening of the mangoes. The total repining time period was divided into five stages (RS I-V). At each stage mangoes were washed and peeled to remove pulp.

Extract preparation and synthesis of NPs

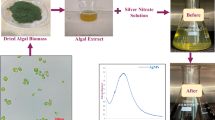

Mango pulp pieces (20 g) were homogenized with 100 ml of deionized water at high speed in a homogenizer for 2 min. The homogenate was left to stand overnight and then filtered through Whatman filter paper No. 4. The filtrate was used for the synthesis of nanoparticles (NPs).

For the synthesis of Ag NPs, 50 ml of freshly prepared mango pulp extract (pH 8) was placed in a flask, and 2.125 g of silver nitrate salt was added. The mixture was stirred on a magnetic stirrer at 50 °C and 1100 rpm for 1.5 h. To prevent light exposure, the flasks were completely covered with aluminum foil. After the reaction was completed, the precipitates were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 25 °C. The resulting pellets were washed three times with distilled water, with resuspension of the pellets each time. The pellets were then dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h, followed by grinding in a mortar and pestle.

Characterization of nanoparticles

At the completion of reaction, synthesis of Ag NPs, UV-vis spectra was recorded from 300 to 700 nm wavelength using MULTISKAN SKYHIGH and FC Microplate Spectrophotometer.

The powder X-ray diffraction of Ag nanoparticles was done by using D8 advanced having Cukα radiation source of 1.54Å with 1200-watt X-rays energy. The scanning was carried out in range of 2θ from 20º-70º. The data obtained was used to calculate the crystalline size using Debye Scherer equation as.

Where D represents the crystal size, λ is CuKα wavelength (1.54 A), θ is diffraction angle and β is full width at half maxima (FWHM) of the diffraction peak (in radian).

FTIR of synthesized Ag nanoparticles was done using nicoletTM380 pressed with KBr, made into pellets and was done to identify the biomolecules responsible for reduction and capping of green synthesized Ag nanoparticles. The dried pellets of samples were used to test the surface functional groups by FTIR spectroscopy where it was scanned between 400 and 4000 cm-1 in the transmittance mode.

The morphology of Ag NPs was investigated using Scanning electron microscopy SEM (MIRA3 TESCAN) operating at acceleration voltage of 20 kV. Thin films of samples were prepared on silicon wafer by dropping a small amount of sample on silicon wafer.

Radical scavenging, antioxidant and reducing power activity of NPs

The free radical scavenging capacity of the nanoparticles (NPs) was determined using the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl (DPPH) radical discoloration method27. To determine DPPH radical scavenging activity, 180 µl of a methanol solution of DPPH (9.2 mg/100 ml) was added to separate wells of a 96-well plate. NPs samples (20 µl of 4 mg/ml in DMSO) were then added to each well, mixed, and allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a microplate reader. The scavenging activity in percent (%RSA) was calculated using the equation:

where A0 is the absorbance of the negative control containing only the reagent, and A1 is the absorbance of the reaction mixture or standards. Ascorbic acid was used as the positive control, and the assay was performed in triplicate.

Total antioxidant capacity was assessed using a modified method described by Sajjad et al.28. The activity was measured by mixing 0.1 ml of NP solution (4 mg/ml in DMSO) with 1 ml of reagent solution (0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28 mM sodium phosphate, and 4 mM ammonium molybdate). Ascorbic acid was used as the positive control, and DMSO as the negative control. The reaction solution was incubated in a boiling water bath at 95 °C for 90 min. After cooling to room temperature, the absorbance of the solutions was measured at 695 nm against a blank. The antioxidant activity was expressed as µg ascorbic acid equivalent per mg NPs (µg AAE/mg NPs).

The reducing power of the NPs was measured using a potassium ferricyanide colorimetric assay according to the method described by Sajjad et al.28. To assess reducing power, 200 µl of NPs solution (4 mg/ml in DMSO) was mixed with 400 µl of phosphate buffer (0.2 mol/l, pH 6.6) and 1% potassium ferricyanide [K3Fe(CN)6]. The mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 20 min. Trichloroacetic acid (400 µl of 10%) was added to the mixture, which was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm at room temperature for 10 min. The upper layer of the solution (500 µl) was mixed with 500 µl of distilled water and 100 µl of FeCl3 (0.1%). The absorbance was measured at 700 nm, with increased absorbance indicating increased reducing power. A blank was prepared by adding 200 µl of DMSO to the reaction mixture instead of the extract. The reducing power of each sample was expressed as µg ascorbic acid equivalent per mg NPs (µg AAE/mg NPs), and the assay was performed in triplicate.

Phenolic-like and flavonoid-like property of NPs

The phenolic-like property of the NPs was determined spectrophotometrically using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent method with slight modifications29. An aliquot of 20 µl from 4 mg/ml DMSO stock solution of each test sample was transferred to separate wells of a 96-well plate, followed by the addition of 90 µl of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. The plate was incubated for 5 min, after which 90 µl of sodium carbonate was added to the reaction mixture. Gallic acid was used as the standard, and the absorbance of each reaction mixture was taken at 630 nm using a microplate reader (Biotech USA, microplate reader Elx 800). The phenolic-like property was determined in triplicate and expressed as µg gallic acid equivalent per mg NPs (µg GAE/mg NPs).

The flavonoid-like property of the NPs was estimated using the aluminum chloride colorimetric method described by Nadeem et al.29. NPs samples (20 µl of 4.0 mg/ml in DMSO) were transferred to separate wells of a 96-well plate. Subsequently, 10 µl each of 10% aluminum chloride and 1.0 M potassium acetate were added, followed by the addition of 160 µl of distilled water. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was then measured at 415 nm using a microplate reader. Quercetin was used as the standard, and the flavonoid content was expressed as µg quercetin equivalent per mg NPs (µg QE/mg NPs).

Statistical analysis

All assays were performed in triplicate. Results are reported as mean ± standard error. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the means were compared using LSD at a 0.05% probability level (p < 0.05).

Results and discussion

When mango pulp extract was supplemented with silver nitrate, the color change from light yellow/yellow to dark brown or black is the first indication of formation of silver nanoparticles. UV-visible spectrophotometer analysis showed peaks at around 400 nm, with the RSIII based extract showing the highest absorption, followed by RSIV and others (Fig. 1). The phytochemicals in the extracts are responsible for converting silver ions into nanoparticles. It can be inferred that at RSIV, the concentration of metabolites capable of converting ions into nanoparticles is highest. At other ripening stages, the concentrations of such biomolecules may be lower or they may be in conjugated forms, making them less available for the reduction of metal ions. Green synthesis is favored for nanoparticle production due to its cost-effectiveness, use of non-toxic chemicals, and eco-friendly method. The intersection of nanotechnology and green chemistry has led to the development of cytologically and biologically compatible silver nanoparticles. Among various synthesis strategies, green methods for silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) have proven to be the most promising and applicable in biological systems30,31.

The initial color change is the first indication of silver ion reduction by biomolecules in the mango pulp extract32,33,34. UV-vis absorption spectroscopy, which relies on surface plasmon resonance, shows spectra that depend on particle size, shape, state of aggregation, and the surrounding dielectric medium35. It is well known that an absorption band appears at 400–440 nm due to surface plasmon resonance of Ag nanoparticles36,37. The peak shift is likely due to changes in the size and/or anisotropy of the silver particles38.

Mango pulp contains variety of phenolic, carboxyl and hydroxyl biomolecules that reduce the silver ions to NPs. On the other hand Ag2O might also be intermediate stage before formation of Ag NPs. The charges on the biomolecules and silver ion either have steric hindrance or electrostatic attraction resulting smaller NPs size or agglomeration, respectively39,40. Furthermore along with reduction process, the biomolecules also cap on the NPs that stabilize NPs, reduce toxicity, increase biocompatibility, and manifest the activities27.

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) of NPs

FTIR analysis is performed for optical characterization and identification of linked functional groups. The NPs samples showed variations in peak wavenumbers, indicating changes in the phytochemical composition of the pulp extracts that were involved in the reduction of ions and capping process of NPs (Fig. 2, Figure S1)). Peaks below 1000 cm⁻¹ indicate the presence of –O-H groups of carboxylic acids. The presence of peaks at 900 cm⁻¹ suggests aromatics on the surface of the NPs. Consistent peaks were observed at 900–1000 cm⁻¹ (C-H stretching of aliphatic acids), 1600–1750 cm⁻¹ (-CHO, -C = O, -COOH stretching of carboxylic groups), and 3000–3200 cm⁻¹ (aldehydes and ketones). Many reports disclose these peaks when NPs were formulated by the biological processes41,42. In case of use of pant extract for synthesis of NPs, such peaks generally correspond to = CH2 or –CH = CH-, -C = C- or –C = O, and –C-H(CH2) or -OH stretches, respectively indicating presence of diverse molecules in plant extracts. All samples except RSIII sample also showed prominent peaks at 600–700 cm⁻¹, corresponding to alkyl halides or halogens. The peak intensities in RSII and RSIII were lower compared to other samples. Additionally, minor peaks were also observed, indicating the presence of other functional groups. The variable intensities of the peaks suggest different concentrations of phytochemicals at different ripening stages. The FTIR spectra indicate that these functional groups are responsible for the reduction and stabilization of silver nanoparticles31,43,44,45.

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis of NPs

The XRD pattern showed the absorbance of diffraction peaks of silver nanoparticles at 2θ. The Scherrer equation was used to estimate the particle size based on prominent peaks. The particle size was ranged from 2.11 nm to 11.72 nm for silver nanoparticles synthesized from mango extracts of different ripening stages (Fig. 3, Figure S2). The diffraction angles and lattice planes are presented in Table 1. The multiple peaks and specific angles have been reported for silver NPs synthesized by green chemistry44,46. The major peaks were at the same angles as reported for green synthesized NPs and JCPDS standards 04-0783. Variation in peaks intensity and angle change shift was observed in XRD diffrectograms. Such changes might be due to spacing in between the atoms of Ag NPs, attachment of biomolecules, number of atoms per NPs and size variation35,47. The high-strength peaks in the pattern correspond to silver nitrate nanoparticles, suggesting the material was crystalline. The XRD patterns are consistent with earlier reports48,49.

The variation in the number of peaks and angle shifts might also be due to the primary and secondary reduction of silver ions at the nucleation site and growth interfaces, respectively. The time-based reduction process increases the size of NPs, and the diversity of biomolecules in extracts has a bridging effect and causes NPs aggregation50,51. Thus, variations in NPs size distribution, number of peaks, and peak intensity were observed with mango pulp extracts of different ripening stages.

SEM analysis of Ag NPs

The SEM images show that the Ag NPs synthesized by extracts of mango pulp at different ripening stages were irregular in shape (Fig. 4). The clumping was observed at all the stages however coagulation was more when RS IV and RS V extract was used for synthesis of Ag NPs. This might be due to higher carbohydrate content at the stage IV and V.

EDX analysis shows percent metal content in NPs. The highest concentration of silver shows formation of silver NPs that were fortified with oxygen and carbon atoms (Table 2). The NPs synthesized by RSII extract showed highest concentration of Ag that gradually reduced when lateral ripening stages pulp extracts were used for synthesis of NPs. At the same extent oxygen and carbon concentrations also gradually increased. This shows that as the mango ripening proceed, oxygen and carbon bearing molecules were more available for interaction with silver ions or NPs.

Antioxidative response of NPs

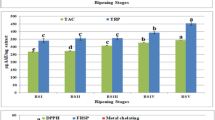

The relative ability of silver NPs to scavenge free radicals was assessed using the DPPH test. The NPs synthesized using RSIII stage extract showed 51% radical scavenging activity, while RSIV exhibited 45.87% activity (Fig. 5). Other NPs had low power to scavenge free radicals. The total antioxidant capacity assay, commonly used to test the antioxidant response of samples against free radicals, revealed strong antioxidant capacities of 80.22 and 79.14 µg AAE/mg NPs for NPs synthesized by RSI and RSIV extracts, respectively. NPs synthesized from RSIII extract showed the least activity at 61.47 µg AAE/mg (Fig. 5). Metallic nanoparticles exhibit antioxidant properties, enabling them to scavenge free radicals and reduce ROS concentrations that exceed normal levels during illness. Due to these properties, NPs are also referred to as nano-antioxidants28. These NPs possess intrinsic antioxidative property due to the attachment of entire biomolecules or just functional groups on their surface52,53. Consequently, the antioxidant properties depend on the synthesis medium, chemical composition, nature, stability, surface-to-volume ratio, size, surface coating, and surface charge54,55.

The total reduction potential was found to be 28.67 µg AAE/mg for NPs synthesized from RSII stage mango extract. RSI, RSIII and RSV exhibited approximately the same activity (22 µg AAE/mg NPs) (Fig. 5). In the total reduction potential assay, compounds with reduction potential combine with Fe2+ (potassium ferricyanide) to form Fe2+ (potassium ferrocyanide), which reacts with ferric chloride to create a ferric-ferrous complex56,57.

DPPH based free radical scavenging activity, total antioxidant potential, and total reducing power potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized by mango ripening stages extracts. Values represent means ± standard error where n = 3. The different letters on the bars mean statistical difference between treatments (ANOVA LSD, p ≤ 0.05).

NPs synthesized from RSIV extract showed 70.84 µg GAE/mg NPs phenolic-like property, followed by RSII with 58.17 µg GAE/mg NPs (Fig. 6). For flavonoid-like activity, RSII and RSIV exhibited 35.37 and 25.98 µg GAE/mg NPs activity, respectively (Fig. 6). The free radical scavenging activity of NPs is attributed to the presence of functional groups on their surface or the attachment of biomolecules present in the extract during the green synthesis approach. Therefore, phenolic and flavonoid properties were also assessed.

Numerous studies on the antioxidant activity of silver nanoparticles have been published in recent years35,58. The antioxidant properties of Ag NPs largely depend on the extract used for synthesis of NPs55,59. The abundance of surface-generated flavonoids and phenolics as capping agents likely contributes to the antioxidant activity of these nanoparticles. Antioxidant assays evaluate the activity of any sample based on its potential to donate hydrogen atoms or electrons. Phenols and flavonoids are potent antioxidants that act as hydrogen donors, reducing agents, and oxygen quenchers29,60,61. The antioxidant potential is related to the association of functional groups on the NPs surface or the structural properties of the nanomaterials. The results indicate that mango ripening stages contain diverse phytochemicals crucial for NPs synthesis and biological activities. These activities may result from the capping of biomolecules on the NPs surface or different functional groups detaching from biomolecules and binding with NPs58,62,63. The biological activities and presence of biomolecules on the surface of NPs make them biocompatible and suitable for various biological systems. This studs has shown that silver nanoparticles possess free radical scavenging properties and protective effects against oxidative damage, thus providing antioxidative potential64,65.

Conclusions

In summary, sufaid chonsa mango pulp at various stages of ripening (RSI-RSV) is capable of synthesizing silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) with distinct morphological features and antioxidative properties. The biochemical changes that occur as the mango ripens, such as fluctuations in sugar content, acidity, and phenolic compounds, significantly influence the synthesis process. These variations lead to the formation of Ag NPs with different shapes, sizes, and structural characteristics. Consequently, the antioxidative properties of the nanoparticles are also affected, with each ripening stage offering unique advantages for specific applications (Fig. 7). These findings underscore the importance of considering the ripening stage of mango pulp when optimizing the synthesis of Ag NPs for targeted use in areas such as medicine, food technology, and environmental science.

Data availability

All the relevant data are reported in the manuscript.

References

Maldonado-Celis, M. E. et al. Chemical composition of mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit: nutritional and phytochemical compounds. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1073 (2019).

Yadav, D., Pal, A. K., Singh, S. P. & Sati, K. Phytochemicals in mango (Mangifera indica) parts and their bioactivities: a review. Crop Res. 57(1and2), 79–95 (2022).

Yahya, S. M. et al. Biological synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial effect of silver nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) using aqueous extract of mango pulp (Mangifera indica). J. Complement. Altern. Med. Res. 13(4), 39–50 (2021).

Masibo, M. & He, Q. Major mango polyphenols and their potential significance to human health. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 7(4), 309–319 (2008).

Kumar, M. et al. Mango (Mangifera indica L.) leaves: nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, and health-promoting bioactivities. Antioxidants. 10(2), 299 (2021).

Rafique, M., Sadaf, I., Rafique, M. S. & Tahir, M. B. A review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their applications. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 45(7), 1272–1291 (2017).

Ahmad, S. et al. Green nanotechnology: a review on green synthesis of silver nanoparticles—An ecofriendly approach. Int. J. Nanomed., 5087–5107. (2019).

Mittal, A. K., Chisti, Y. & Banerjee, U. C. Synthesis of metallic nanoparticles using plant extracts. Biotechnol. Adv. 31(2), 346–356 (2013).

Sarkar, R., Kumbhakar, P. & Mitra, A. K. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its optical properties. Digest J. Nanomaterials Biostructures. 5(2), 491–496 (2010).

Abou El-Nour, K. M., Eftaiha, A. A., Al-Warthan, A. & Ammar, R. A. Synthesis and applications of silver nanoparticles. Arab. J. Chem. 3(3), 135–140 (2010).

Burdusel, A. C. et al. Biomedical applications of silver nanoparticles: an up-to-date overview. Nanomaterials. 8(9), 681 (2018).

Verma, P. & Maheshwari, S. K. Applications of silver nanoparticles in diverse sectors. Int. J. Nano Dimension. 10(1), 18–36 (2019).

Xing, Y. et al. Characterization and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized with the peel extract of mango. Materials. 14(19), 5878 (2021).

Endah, E. S. et al. Phyto-assisted synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using mango (Mangifera indica) fruit peel extract and their antibacterial activity. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 1201, No. 1, 012081. (IOP Publishing, 2023).

Samari, F., Salehipoor, H., Eftekhar, E. & Yousefinejad, S. Low-temperature biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using mango leaf extract: catalytic effect, antioxidant properties, anticancer activity and application for colorimetric sensing. New J. Chem. 42(19), 15905–15916 (2018).

Narayana, A., Azmi, N., Tejashwini, M., Shrestha, U. & Lokesh, S. V. Synthesis and characterization of zinc oxide (zno) nanoparticles using mango (Mangifera indica) leaves. IJRAR-International J. Res. Anal. Reviews (IJRAR). 5(3), 432–439 (2018).

Muralikrishna, T., Malothu, R., Pattanayak, M. & Nayak, P. L. Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Mangifera indica (mango leaves) aqueous extract. World J. Nanosci. Technol. 2, 66–73 (2014).

Guamán-Balcázar, M. C. et al. Generation of potent antioxidant nanoparticles from mango leaves by supercritical antisolvent extraction. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 138, 92–101 (2018).

Cheng, J. et al. Preparation of a multifunctional silver nanoparticles polylactic acid food packaging film using mango peel extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 188, 678–688 (2021).

Salati, S., Doudi, M. & Madani, M. The biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles by mango plant extract and its anti-candida effects. J. Appl. Biotechnol. Rep. 5(4), 157–161 (2018).

Yang, N. & Li, W. H. Mango peel extract mediated novel route for synthesis of silver nanoparticles and antibacterial application of silver nanoparticles loaded onto non-woven fabrics. Ind. Crops Prod. 48, 81–88 (2013).

Shamim, M. & Maz, A. Mango pulp mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles: structural characterization and application as antimicrobial agent. Int. J. Recent. Trends Eng. Res. 3, 190–194 (2017).

Hussain, A. et al. Physiological and biochemical variations of naturally ripened mango (Mangifera Indica L.) with synthetic calcium carbide and ethylene. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 2121 (2024).

Li, D. et al. Ripening induced degradation of pectin and cellulose affects the far infrared drying kinetics of mangoes. Carbohydr. Polym. 291, 119582 (2022).

Liu, B. et al. Research progress on mango post-harvest ripening physiology and the regulatory technologies. Foods. 12(1), 173 (2022).

Wu, S. et al. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal new insights into the role of abscisic acid in modulating mango fruit ripening. Hortic. Res. 9, uhac102 (2022).

Awan, S., Sajjad, A., Ali, Z. & Zia, M. Physiochemical and biological evaluation of stirrer-and autoclaved-based syntheses of cerium oxide nanoparticles using ginger (Zingiber officinale) extract. Emergent Mater., 1–10. (2024).

Sajjad, A., Bhatti, S. H. & Zia, M. Photo excitation of silver ions during the synthesis of silver nanoparticles modify physiological, chemical, and biological properties. Part. Sci. Technol. 41(5), 600–610 (2023).

Nadeem, A., Naz, S., Ali, J. S., Mannan, A. & Zia, M. Synthesis, characterization and biological activities of monometallic and bimetallic nanoparticles using Mirabilis jalapa leaf extract. Biotechnol. Rep. 22, e00338 (2019).

Sivakumar, T. A modern review of silver nanoparticles mediated plant extracts and its potential bioapplications. Int. J. Bot. Stud. 6(3), 170–175 (2021).

Asghar, M. et al. Comparative analysis of synthesis, characterization, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and enzyme inhibition potential of roses petal based synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Chem. Phys. 278, 125724 (2022).

Chakravarty, A. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using fruits extracts of Syzygium cumini and their bioactivity. Chem. Phys. Lett. 795, 139493 (2022).

Tailor, G., Yadav, B. L., Chaudhary, J., Joshi, M., & Suvalka, C. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum canum and their anti-bacterial activity. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 24, 100848. (2020).

Zia, M. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from grape and tomato juices and evaluation of biological activities. IET Nanobiotechnol. 11(2), 193–199 (2017).

Jabbar, A. H. et al. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticle (AgNPs) using pandanus atrocarpus extract. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 29(3), 4913–4922 (2020).

Sougandhi, P. R. & Ramanaiah, S. Green synthesis and spectral characterization of silver nanoparticles from Psidium guajava leaf extract. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 50(12), 1290–1294 (2020).

Noguez, C. Surface plasmons on metal nanoparticles: the influence of shape and physical environment. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111(10), 3806–3819 (2007).

Yap, Y. H. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticle using water extract of onion peel and application in the acetylation reaction. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 45, 4797–4807 (2020).

Alharbi, N. S., Alsubhi, N. S. & Felimban, A. I. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using medicinal plants: characterization and application. J. Radiation Res. Appl. Sci. 15(3), 109–124 (2022).

Guibaud, G., Tixier, N., Bouju, A. & Baudu, M. Relation between extracellular polymers’ composition and its ability to complex cd, Cu and Pb. Chemosphere. 52(10), 1701–1710 (2003).

Farinella, N. V., Matos, G. D. & Arruda, M. A. Z. Grape bagasse as a potential biosorbent of metals in effluent treatments. Bioresour. Technol. 98(10), 1940–1946 (2007).

Ahmad, K. et al. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles through the Piper cubeba ethanolic extract and their enzyme inhibitory activities. Front. Chem. 11, 1065986 (2023).

Azwatul, H. M. et al. Plant-based green synthesis of silver nanoparticle via chemical bonding analysis. Mater. Today Proc. (2023).

Butt, A., Ali, J. S., Sajjad, A., Naz, S. & Zia, M. Biogenic synthesis of cerium oxide nanoparticles using petals of Cassia glauca and evaluation of antimicrobial, enzyme inhibition, antioxidant, and nanozyme activities. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 104, 104462 (2022).

Wasilewska, A. et al. Physico-chemical properties and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles fabricated by green synthesis. Food Chem. 400, 133960 (2023).

Dua, T. K. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Eupatorium adenophorum leaf extract: characterizations, antioxidant, antibacterial and photocatalytic activities. Chem. Pap. 77(6), 2947–2956 (2023).

Viswanathan, S. et al. Synthesis, characterization, cytotoxicity, and antimicrobial studies of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using red seaweed Champia parvula. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14(6), 7387–7400 (2024).

Safa, M. A. T. & Koohestani, H. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles with green tea extract from silver recycling of radiographic films. Results Eng. 21, 101808 (2024).

Reichel, H. et al. Nucleation and growth of plasma sputtered silver nanoparticles under acoustic wave activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 669, 160566 (2024).

Ahmadi, F. & Lackner, M. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Cannabis sativa: Properties, synthesis, mechanistic aspects, and applications. ChemEngineering. 8(4), 64 (2024).

U-Din, M. M. et al. Green Synthesis and characterization of biologically synthesized and antibiotic-conjugated silver nanoparticles followed by post-synthesis assessment for antibacterial and antioxidant applications. ACS Omega. 9(17), 18909–18921 (2024).

Tufail, S., Ali, Z., Hanif, S., Sajjad, A. & Zia, M. Synthesis and morphological & biological characterization of Campsis radicans and Cascabela thevetia petals derived silver nanoparticles. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 105, 104526 (2022).

Javed, R., Zia, M. & Cheema, M. Capping agents encapsulated nanoparticles in plant biotechnology. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1158624 (2023).

Bhavi, S. M. et al. Green synthesis, characterization, antidiabetic, antioxidant and antibacterial applications of silver nanoparticles from Syzygium Caryophyllatum (L.) Alston leaves. Process Biochem. 145, 89–103 (2024).

Al Baloushi, K. S. Y. et al. Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Moringa Peregrina and their toxicity on MCF-7 and Caco-2 human cancer cells. Int. J. Nanomedicine, 3891–3905 (2024).

Konduri, V. V. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Hibiscus tiliaceus L. leaves and their applications in dye degradation, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities. South. Afr. J. Bot. 168, 476–487 (2024).

Zia, M. et al. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles from grape and tomato juices and evaluation of biological activities. IET Nanobiotechnol. 11(2), 193–199 (2017).

Suresh, P., Doss, A., Praveen Pole, R. P. & Devika, M. Green synthesis, characterization and antioxidant activity of bimetallic (Ag-ZnO) nanoparticles using Capparis Zeylanica leaf extract. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 14(14), 16451–16459 (2024).

Naz, S. et al. Kinnow peel extract as a reducing and capping agent for the fabrication of silver NPs and their biological applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 11(8), 1040–1045 (2017).

Ali, A. et al. Synthesis of Ag-NPs impregnated cellulose composite material: its possible role in wound healing and photocatalysis. IET Nanobiotechnol. 11(4), 477–484 (2017).

Javed, R. et al. Role of capping agents in the application of nanoparticles in biomedicine and environmental remediation: recent trends and future prospects. J. Nanobiotechnol. 18, 1–15 (2020).

Sharifi-Rad, M., Elshafie, H. S. & Pohl, P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by Lallemantia royleana leaf extract: their bio-pharmaceutical and catalytic properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol., a. 448, 115318 (2024).

Suleman, M., Ali, J. S., Nisa, S. & Zia, M. Antioxidative, protein kinase inhibition and antibacterial potential of seven mango varieties cultivated in Pakistan. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci., 32(4). (2019).

Habeeba, U. & Raghavendra, N. Green synthesis and antioxidant potency of silver nanoparticles using arecanut seed extract. Nano-Structures Nano-Objects. 38, 101118 (2024).

Ali, J. S. et al. Antimicrobial, antioxidative, and cytotoxic properties of Monotheca Buxifolia assisted synthesized metal and metal oxide nanoparticles. Inorg. Nano-Metal Chem. 50(9), 770–782 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AB performed the experiments, wrote the manuscript. ZMR supervised the work, and proofread the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aniqa, Rizvi, Z.F. Physio-chemical analysis and antioxidative response of Ag NPs synthesized by sufaid chonsa mango pulp extracts of different ripening stages. Sci Rep 14, 28514 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78725-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78725-4