Abstract

This research explores the efficacy of integrating nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom systems in the vibration control of rod coupling systems. By interlinking two rods with a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system as the intermediary, the study employs the Lagrange method (LM) to forecast nonlinear vibrational behaviors. The findings, substantiated by numerical analyses, affirm the precision of LM in gauging the amplitude responses when such a nonlinear system is utilized. The nonlinear dynamics, characterized by intricate vibrational patterns, peak jumping phenomena, and the migration of resonance zones, are induced by the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system. By fine-tuning the system’s parameters, significant alterations in the vibrational states of the rod coupling system are achievable. This suggests that the application of a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system is a viable strategy for modulating vibrations in rod systems. Furthermore, optimal parameterization of this system is proven to effectively dampen vibrations, showcasing its potential as a sophisticated mechanism for vibration suppression in coupled rod configurations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vibrational forces, caused by power machinery and working conditions, are prevalent across diverse engineering disciplines, invariably inducing structural vibrations. These vibrations often pose a risk to the integrity and stability of engineering structures. Thus, understanding and controlling these vibrational characteristics is fundamental. For analytical simplicity, many engineering structures can be conceptualized as assemblies of elemental units such as rods, beams, and plates. This modular approach allows for a more manageable examination of the structures’ vibrational properties.

In the machining engineering domain, the durability of boring bar systems is pivotal, and it hinges on controlling structural vibrations. Engineers have thus scrutinized the vibration characteristics of the rod system, the basic unit of the boring bar. Tang et al.1 explored rods with complex boundary conditions, while Pritz2 looked into the dynamic strain of viscoelastic rods with added end masses. Gürgöze3 meticulously studied the specific frequencies of rod systems with a tip mass and mid-span spring-mass arrangements. Candan and Elishakoff4 calculated the axial stiffness of rods based on their primary vibrational shapes, and Erol5 addressed the characteristic equations for internally supported rod systems with an end mass. Mei6 conducted a thorough analysis of four rod theories, enhancing the application of vibration theory in rod systems. Goldberg et al.7 investigated the movement at the contact points of rod systems under longitudinal vibrational forces, while Aydogdu8 considered axial vibrations in nanorods within a nonlocal continuum model. Xu et al.9,10 applied an improved Fourier series method to study the longitudinal vibrations of nonlocal nanorods with various boundary conditions and supports. The field also delves into nonlinear vibrations; Cao and Tucker11 employed Cosserat theory for the nonlinear dynamics of elastic rods. Andrianov et al.12 researched the nonlinear vibrations of a rod with a microstructure. Considering rods with variable cross-sections and fractional derivative elements, Malara et al.13 explored nonlinear stochastic vibrations, and Shakhlavi et al.14 analyzed internal resonances in nanorod systems. These studies offered an extensive investigation into both the forced and natural vibrational characteristics of single-rod structures.

In the analysis of complex rod systems, academic inquiry has focused on the longitudinal vibrations of coupled rod configurations. Tomski et al.15 examined the vibrations within a compound two-rod system, while Kukla et al.16 explored how translation springs affect the vibrational behavior of two interconnected rods. Gürgöze17 introduced alternative frequency equations to assess the vibrations of rods linked by a dual spring-mass system. The work of Mermertas and Gürgöze18 extended this to the longitudinal vibrations of a double-rod system joined by two spring-mass systems. Li et al.19 derived exact solutions for the vibrational characteristics of rod systems coupled by translational springs. In scenarios involving multiple coupling spring-mass systems, Inceoğlu and Gürgöze20 analyzed the longitudinal vibrations, and Erol and Gürgöze21 studied the vibration characteristics of double-rod systems connected by an array of springs and dampers. Lin et al.22 investigated th23e free vibration characteristics of two rods coupled by multiple spring-mass systems. Zhao et al studied the nonlinear vibration responses of a double-rod system connected by a nonlinear element. Collectively, these studies offered a systematic examination of the longitudinal vibration characteristics of two-rod systems coupled by single, dual, and multiple spring-mass systems, within the context of linear dynamics.

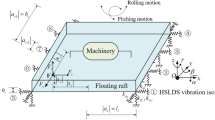

Amidst the evolution of nonlinear vibration control theory, researchers have been experimenting with nonlinear elements to devise mechanisms for mitigating the vibrations of elastic structures. A particular focus has been on using cubic stiffness to craft nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom systems. These systems, devoid of linear stiffness components, are termed nonlinear energy sinks (NESs)22,23,25. Felix et al.27 deeply studied the energy pumping, synchronization and beat phenomenon in a nonideal structure coupled to an essentially nonlinear oscillator. Georgiades and Vakakis28 pioneered the integration of NES into a linear beam to assess its vibration control capabilities. Subsequently, Ahmadabadi and Khadem29 explored the nonlinear vibration control of a cantilever beam using NES. Kani et al.30 designed an NES considering various support conditions and utilized it to dampen vibrations in a linear beam. They also investigated31 the vibration control of a nonlinear beam via NES. Felix et al.32 introduced a nonlinear energy sink into the nonlinear electromechanical pendulum arm, promoting its engineering application. Chen et al.33 examined the suppression of vibrations in a beam system by incorporating parallel NESs, paying special attention to the system’s higher branch responses. The effectiveness of NES in an axially moving beam system was also studied by Moslemi et al.34, focusing on both vibration control and system stability. Zhang et al.35 introduced boundary inerter-enhanced NESs to quell vibrations in elastic beams, and in a separate study36, they controlled vibrations in geometrically nonlinear beams using boundary inertial NESs. Further extending the application, He et al.37 combined acoustic black hole effects with NES in a cantilevered beam to mitigate both low and high-frequency vibrations. Zhao et al.38,38,39,40,42 utilized adjustable nonlinear vibration absorbers, nonlinear energy sinks, and coupling nonlinear energy sinks for the vibration control of beams, plates, and vibroacoustic coupling systems and further43,44 connected elastic structures with nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom systems to study its dynamic behavior. Furthermore, Zhan et al46 used a nonlinear connecting intercalary plate and connecting nonlinear oscillators to hybrid suppress the vibration of a simplified floating raft system. Ding and Shao45 first proposed the concept of NES cells and they47 employed NES cells to effectively control the vibration of a plate platform. Tusset et al.48,49 introduced nonlinear energy sinks to the high-speed elevator system and a portal frame, finding that nonlinear energy sinks can be employed to harvest the vibration energy of various engineering structures, promoting the engineering application of nonlinear energy sinks. The prevailing literature has largely centered on the vibration control of elastic beams, plates, and their coupling systems, through the use of nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom systems, often in the form of NESs. However, the application of these systems as coupling elements in rod systems remains under-explored, with limited attention given to their potential in controlling vibrations in such configurations.

To promote the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom systems in the engineering application of rod systems, having an understanding of the influence of nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom systems on the longitudinal dynamic behavior of the rod system is necessary. Against this background, this research evaluates the use of nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom systems in managing vibrations within rod coupling assemblies. A nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system is introduced as the coupling mechanism linking two rods. Utilizing LM, the study predicts the nonlinear vibrational responses when two rods are conjoined by such a system. Through numerical analysis, the precision and robustness of LM in deducing the vibratory behavior of the coupled rods are examined. The study meticulously analyzes how the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system influences the magnitude-frequency and single-frequency responses of the rod coupling system. Ultimately, the study arrives at several key conclusions regarding the system’s performance.

Theoretical formulations

Model description

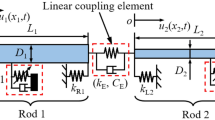

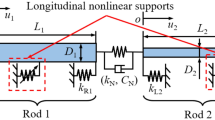

This study presents a model for the longitudinal vibrations of a rod system composed of two rods linked by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system, as depicted in Fig. 1. The system comprises two sub-rods and a nonlinear coupling element. Vibrational forces, exhibiting harmonic properties, act upon sub-rod 1. Longitudinal support springs, representing general boundary conditions, are positioned at the ends of each sub-rod. Table 1 enumerates the specific parameters for the sub-rods, the vibrational forces, and the support springs. Additionally, ui(xi,t) denotes the displacement of the ith sub-rod.

where kL is the linear stiffness of the nonlinear single-degree-freedom system; kN is the cubic stiffness of the nonlinear single-degree-freedom system; CN is the viscous damping of the nonlinear single-degree-freedom system; uN is the vibration displacement of the nonlinear single-degree-freedom system; and mN is defined as the motion mass of the nonlinear single-degree-freedom system.

LM is applied to analyze the vibrational responses of the coupled rod system. To do this, it is essential to formulate Lagrangian, which encapsulates the system’s kinetic energy, potential energy, and the work done by external forces. Building on these principles, the research progresses to derive the expressions for the energy terms specific to the coupled rod system.

According to the above derivation, the kinetic energy (TN), potential energy (VN), and work done by the viscous damping force (WN) can be derived as follows:

and

Based on the vibration theory, the kinetic energy (TRi) and potential energy (VRi) of sub-rods can be determined as follows:

and

The work done by the vibration excitation (WE) is derived as follows:

The potential energy of the longitudinal boundary springs (VBi) is expressed as follows:

Based on the above forms of energy terms, the total kinetic energy (TSystem), total potential energy (VSystem), and total work done by the external force (WSystem) can be determined as follows:

and

Therefore, Lagrange term of two rods coupled through a nonlinear single-degree-freedom system can be developed as follows:

When using LM to forecast the vibrational responses of two rods linked by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system, the Lagrange term represents the total energy of the system is of great importance.

Solution procedure

Following the mode superposition method, the vibrational displacements of the two sub-rods are expressed in an expanded form as follows:

and

where φ1j(x1) and φ2j(x2) are the modal functions of sub-rods; q1j(t) and q2z(t) are the unknown coefficients; and M and Z are the number of truncations.

To simply establish Lagrange function, the vibrational displacements of the sub-rods are reformed into specific terms, which are outlined as follows:

and

where the form terms shown in Eq. (9) are listed as,

and

To ensure the uniformity of the solution procedure, q3 is defined as follow:

By substituting Eqs. (10) and (11) into Eq. (7) and proceeding with the subsequent step:

The Lagrange function, representing the energy dynamics of two rods coupled through a nonlinear single-degree-freedom system, can be obtained as follows:

and

Vibration responses of two rods coupled through a nonlinear single-degree-freedom system can be obtained by numerically solving Eq. (13). Importantly, the Runge-Kutta method is employed to numerical solve Eq. (13).

Numerical analysis and discussion

This study focuses on deciphering the nonlinear vibrational properties of a system where two rods are connected by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system. The computational methods detailed in Section “Theoretical formulations” are utilized to simulate the system’s nonlinear vibrational responses. The parameters set for the rod system include Young’s modulus Ei = 6.89 × 1010 Pa, ρi = 2.8 × 103 kg/m3, D1 = 0.06 m, D2 = 0.04 m, kLi = kRi = 5 × 104 N/m, xE1 = 0, and F0 = 100 N. The observation points are selected at x1 = L1 for the first rod and x2 = 0 for the second rod. The time domain for calculating the nonlinear vibration is set from 0 to 2000 times the excitation period (TE), with the assumption that the responses within the interval [1801 TE, 2000 TE] will yield stable results. Besides, Fig. 2 gives the flowchart of this section, where the numerical results of this work are analyzed through the corresponding flowchart.

The flowchart of Section “Numerical analysis and discussion”.

Verify the calculation results gained by the LM

This section is dedicated to verifying the accuracy of the results calculated using LM. The parameters for the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system are specified: mN = 0.25 kg, kL = 104 N/m, kN = 108 N/m3, and CN = 10 Ns/m. Prior to affirming the accuracy of these results, it is crucial to confirm their stability. Figure 3 illustrates the magnitude responses of the two-rod system coupled with a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system under various truncation levels. It is observed that the system’s magnitude responses stabilize when LM truncation reaches a single term. Therefore, a truncation value of one is adopted for all further calculations in this study.

Subsequently, to evaluate the accuracy of LM, this study compares the magnitude responses of two rods connected by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system as calculated by LM against those obtained using the harmonic balance method (HBM) and Galerkin truncation method (GTM). For the GTM, the GTM employs the Galerkin condition to discrete the vibration-governing equations of the two rods connected by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system. The detailed process of GTM is the same as those employed in Reference43. It should be noted that the modeling processes of the GTM and LM are quite different. For the HBM, the aimed equations of the HBM are the same as those employed in LM. However, the HBM employs the harmonics to assume the unknown time terms. Considering the nonlinear forms studied in this work is cubic stiffness, the fundamental and third harmonics are employed to simulate the unknown time terms. Then, employing the above harmonics in the aimed equations, one can get a series of functions related to the coefficients of harmonics. Magnitude responses of two rods connected by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system can be obtained by solving the above functions. It should be noted that the HBM calculates the magnitude responses of two rods connected by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system from the frequency domain while the LM calculates those from the time domain. Considering the difference of the above three methods, Fig. 4 displays the magnitude responses derived from LM, HBM, and GTM. The close agreement among the responses from these methods as seen in Fig. 4 suggests that the computational outcomes from LM are reliable.

Figure 5 gives the errors of magnitude responses of two rods coupled through a nonlinear single-degree-freedom system gained by LM, HBM, and GTM. From Fig. 5, it can be found that the errors stay at a reasonable level, which indicates that the computational outcomes from LM are reliable.

Magnitude-frequency vibration impacted by the nonlinear single-degree-freedom system

This section systematically investigates how a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system affects the magnitude-frequency responses of a coupled rod system, aiming to assess its potential for vibration control applications.

Figure 6 illustrates the influence of kN on the magnitude-frequency responses of a two-rod coupling system, where kL is 104 N/m, CE is 10 Ns/m, and mN is 0.2 kg. The results indicate that variations in kN significantly affect the system’s responses. Specifically, increasing kN enhances vibration suppression in sub-rod 1, which is directly subject to vibrational excitation, by broadening the range of effective vibration suppression. However, this increase also intensifies the vibrations in sub-rod 2, indicating a transfer of vibratory energy from sub-rod 1 to sub-rod 2. This effect underscores the importance of selecting an optimal kN value, as excessively increasing kN can adversely affect vibration suppression in sub-rod 1. Additionally, the presence of the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system induces nonlinear vibratory behaviors in the coupling system, as seen when kN is raised to 109 N/m3 and 2 × 109 N/m3. This includes complex vibrations and peak jumping, with resonance regions shifting to higher frequencies, particularly for the 1st resonance region. To further understand the nature of these complex vibrations, Fig. 7 presents phase and time diagrams for different kN values. Figure 7a shows that at kN = 109 N/m3, Poincaré points form a closed curve, and the system demonstrates stable quasi-periodic behavior. In contrast, Fig. 7b reveals that at kN = 2 × 109 N/m3, Poincaré points are disordered, indicating chaotic behavior within a bounded range. This analysis demonstrates that by adjusting the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system’s parameters, particularly kN, one can alter the working condition of the two-rod coupling system, thus influencing its vibrational characteristics.

Phase and time diagrams of compl ex vibration shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 8 presents the magnitude-frequency responses of a two-rod coupling system as influenced by CN, with kL = 104 N/m, kN = 109 N/m3, and mN = 0.2 kg. It is observed that changes in CN significantly affect the system’s responses. At lower CN values, nonlinear vibration phenomena, such as peak jumping and complex vibratory patterns, are evident. As CN increases, these nonlinear effects diminish, and the overall vibration intensity for both sub-rods 1 and 2 decreases. Contrasting with the effects of kN, as discussed in relation to Fig. 6, an increase in CN dampens nonlinear vibrations—a reversal of the trend induced by increasing kN. This underscores the pivotal role of CN in mitigating nonlinear vibrations and reducing overall vibration levels in the two-rod coupling system. Thus, adjusting CN upwards is beneficial for vibration control within this system. Additionally, the characteristics of complex vibrations in Fig. 6 are consistent with those observed in Fig. 6.

Figure 9 depicts the magnitude-frequency responses of a two-rod coupling system impacted by mN, with kL = 104 N/m, kN = 109 N/m3, and CN = 15 Ns/m. An analysis of Fig. 9 reveals that the mass of the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system primarily affects the presence of nonlinear vibration phenomena in the response spectrum. When mN is low, the response of the system is typical. However, as mN is increased to 0.3 kg and 0.4 kg, nonlinear behaviors begin to manifest in the magnitude-frequency responses. The vibration levels of the sub-rods show slight variations with the increase in mN. This observation suggests that mN is a critical factor in either promoting or suppressing nonlinear vibrational phenomena, given a fixed set of other parameters in the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system. To further understand the complex vibrations indicated in Figs. 9 and 10 offers phase and time diagrams for these conditions. Specifically, Fig. 10a corresponds to mN at 0.3 kg, and Fig. 10b to mN at 0.4 kg. In both scenarios, Poincaré points in the phase diagrams form closed loops, and the phase and time diagrams indicate stability, leading to the conclusion that the complex vibration states at these masses are quasi-periodic.

Phase and time diagrams of complex vibration shown in Fig. 7.

Single-frequency vibration influenced by the nonlinear single-degree-freedom system

In engineering applications, the vibrational forces acting on a two-rod coupling system typically remain within a limited range. Therefore, examining how the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system affects the system’s response to a constant-frequency vibration is of considerable importance. In this context, the study sets the vibration excitation frequency at 27.0 Hz to investigate these effects.

Figure 11 illustrates the impact of kN on the magnitude responses of a two-rod coupling system at a single excitation frequency of 27 Hz, with kL = 104 N/m, CN = 15 Ns/m, and mN = 0.3 kg. Observations from Fig. 11 reveal that variations in kN markedly affect the system’s magnitude responses at this frequency. Initially, as kN increases within the range of 108 N/m3 to 108.7 N/m3, the vibration magnitude remains low, indicating effective vibration suppression. However, within the parameter range of [108.7 N/m3, 1011 N/m3], an increase in kN correlates with improved vibration suppression for the coupled system. Moreover, the progression of kN values leads to nonmonotonic changes in the system’s working condition, with three distinct regions exhibiting complex vibrations. Within these regions of complex vibration, the magnitude of the single-frequency response is elevated compared to areas of normal vibration adjacent to them. Therefore, selecting an appropriate range for kN is crucial for optimizing vibration control of the two-rod system when subjected to single-frequency excitation.

Figure 12 provides phase and time diagrams to analyze the complex vibratory states depicted in Fig. 11, at a single excitation frequency of 27 Hz. Figure 12a corresponds to kN of 109.1 N/m3, Fig. 10b to 1010.2 N/m3, and Fig. 10c to 1010.7 N/m3. In Fig. 12a,c, Poincaré points form closed curves in the phase diagrams, indicating a quasi-periodic state due to the stable nature of the phase and time diagrams. Conversely, Fig. 12b shows disordered Poincaré points with fluctuating phase and time diagrams, signifying chaotic behavior at kN = 1010.2 N/m3. This suggests that varying kN influences the working condition of the two-rod system’s single-frequency responses.

Phase and time diagrams of complex vibration shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 13 displays the magnitude responses of a two-rod coupling system at a fixed excitation frequency of 27 Hz, affected by CN, with kL = 104 N/m, kN = 109 N/m3, and mN = 0.3 kg. The data indicates that changes in CN have a significant impact on the magnitude responses at this frequency. Complex vibrational phenomena are observed when CN ranges from 1 Ns/m to 24 Ns/m. Beyond a CN value of 24 Ns/m, the system’s response normalizes, suggesting that higher CN values help eliminate complex vibrations. Additionally, the amplitude of single-frequency vibrations consistently decreases as CN increases, implying that a higher CN is beneficial for reducing vibrations in the two-rod coupling system under single-frequency excitation.

To analyze the complex vibrational state shown in Figs. 13 and 14 provides the corresponding phase and time diagrams. These diagrams demonstrate stability, and Poincaré points form a complete curve. Therefore, it can be concluded that the complex vibration observed in Fig. 13 is in a quasi-periodic state.

Phase and time diagrams of complex vibration shown in Fig. 13.

Figure 15 showcases how mN influences the magnitude responses of a two-rod coupling system at an excitation frequency of 27 Hz, with kL = 104 N/m, kN = 109 N/m3, and CN = 15 N/m. The data indicates that mN significantly affects the system’s responses. Specifically, complex vibrational behaviors emerge when mN is between 0.26 kg and 0.36 kg. Outside this range—below 0.26 kg or above 0.36 kg—the system’s single-frequency responses remain typical. The vibration magnitude fluctuates nonmonotonically with changes in mN, suggesting that adjusting mN is not a straightforward method for controlling vibrations at this frequency. To determine the nature of the complex vibrations indicated in Figs. 15 and 16 provides phase and time diagrams. These diagrams, upon analysis similar to that for Fig. 12, reveal that the complex vibrations are quasi-periodic in nature.

Phase and time diagrams of complex vibration shown in Fig. 15.

Conclusion

This study develops a vibration analysis model for a two-rod coupling system interconnected by a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system. LM is utilized to determine the system’s vibrational responses. The accuracy and stability of LM calculations for this system are verified. Further, the influence of the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system on the system’s magnitude-frequency and single-frequency responses is extensively analyzed. The key findings from the numerical analysis are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

Vibration responses of the model consisting of two rods and a nonlinear single-degree-freedom system can be precisely solved by using LM.

-

(2)

The nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system induces nonlinear vibrational phenomena such as complex vibrations, peak jumping, and shifts in resonance regions. Adjustments to the system’s parameters significantly affect the vibration states of the coupled rods, with changes in kN and CN proving to be effective in vibration control.

-

(3)

The single-frequency vibrational states of the coupled rods can be substantially altered by modifying the parameters of the nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system. Selecting an appropriate range for these parameters is essential for suppressing vibrations under single-frequency excitation.

-

(4)

Overall, incorporating a nonlinear single-degree-of-freedom system is a viable method for controlling vibrations in a two-rod coupling system, with optimal parameterization crucial for effective vibration suppression.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding and first authors upon reasonable request.

References

Tang, J., Li, L. & Huo, Q. Vibration analysis of a rod with complex boundary conditions. Appl. Math. Mech. 9(9), 837–847 (1988).

Pritz, T. Dynamic strain of a longitudinally vibrating viscoelastic rod with an end mass. J. Sound Vib. 85(2), 151–167 (1982).

Gürgöze, M. On the eigenfrequencies of longitudinally vibrating rods carrying a tip mass and spring-mass in-span. J. Sound Vib. 216(2), 295–308 (1998).

Candan, S. & Elishakoff, I. Constructing the axial stiffness of longitudinally vibrating rod from fundamental mode shape. Int. J. Solids Struct. 38, 3443–3452 (2001).

Erol, H. Characteristic equations of longitudinally vibrating rods carrying a tip mass and several viscously damped spring–mass systems in-span. Proc. Institut. Mech. Eng., Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 218(10), 1103–1114 (2004).

Mei, C. Comparison of the four rod theories of longitudinally vibrating rods. J. Vib. Control 21(8), 1639–1656 (2013).

Goldberg, N. N. & O’Reilly, O. M. On contact point motion in the vibration analysis of elastic rods. J. Sound Vib. 487, 115579 (2020).

Aydogdu, M. Axial vibration of the nanorods with the nonlocal continuum rod model. Physica E 41, 861–864 (2009).

Xu, D., Du, J. & Liu, Z. Longitudinal vibration analysis of nonlocal nanorods with elastic end restraints by an improved Fourier series method. Noise Control Eng. J. 64, 766–778 (2016).

Xu, D., Lu, J., Zhang, K., Li, P. & Sun, L. Longitudinal vibration characteristics analysis of nonlocal rod structure with arbitrary internal elastic supports. J. Vib. Control https://doi.org/10.1177/10775463221106534 (2022).

Cao, D. Q. & Tucker, R. W. Nonlinear dynamics of elastic rods using the Cosserat theory: Modelling and simulation. Int. J. Solids Struct. 45, 460–477 (2008).

Andrianov, I. V., Danishevskyy, V. V. & Markert, B. Nonlinear vibrations and mode interactions for a continuous rod with microstructure. J. Sound Vib. 351, 268–281 (2015).

Malara, G., Pomaro, B. & Spanos, P. D. Nonlinear stochastic vibration of a variable cross-section rod with a fractional derivative element. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 135, 103770 (2021).

Shakhlavi, S. J., Shahrokh, H. H. & Nazemnezhad, R. Nonlinear nano-rod-type analysis of internal resonances and geometrically considering nonlocal and inertial effects in terms of Rayleigh axial vibrations. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 137, 420 (2022).

Tomski, L., Przybylski, J. & Geisler, T. Longitudinal vibrations of a compound two-member rod. J. Sound Vib. 168(3), 543–547 (1993).

Kukla, S., Przybylski, J. & Tomski, L. Longitudinal vibration of rods coupled by translation springs. J. Sound Vib. 185(4), 717–722 (1995).

Gürgöze, M. Alternative formulations of the frequency equations of longitudinally vibrating rods coupled by a double spring-mass system. J. Sound Vib. 208(2), 331–338 (1997).

Mermertas, V. & Gürgöze, M. Longitudinal vibrations of rods coupled by a double spring-mass system. J. Sound Vib. 202(5), 748–755 (1997).

Li, Q. S., Li, G. Q. & Liu, D. K. Exact solutions for longitudinal vibration of rods coupled by translational springs. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 42, 1135–1152 (2000).

Inceoğlu, S. & Gürgöze, M. Longitudinal vibrations of rods coupled by several spring-mass systems. J. Sound Vib. 234(5), 895–905 (2000).

Erol, H. & Gürgöze, M. Longitudinal vibrations of a double-rod system coupled by springs and dampers. J. Sound Vib. 276, 419–430 (2004).

Liu, H. P. & Chang, S. C. Free vibrations of two rods connected by multi-spring-mass systems. J. Sound Vib. 330, 2509–2519 (2011).

Zhao Y, Guo F & Xu D. Longitudinal vibration responses of a double-rod system coupled through a nonlinear element. Nonlinear Dyn 112, 1759–1778 (2024).

Felix, J. L. P. & Balthazar, J. M. Comments on a nonlinear and nonideal electromechanical damping vibration absorber, Sommerfeld effect and energy transfer. Nonlinear Dyn. 55, 1–11 (2009).

Ding, H. & Chen, L.-Q. Designs, analysis, and applications of nonlinear energy sinks. Nonlinear Dyn. 100, 3061–3107 (2020).

Saeed, A. S., Nasar, R. A. & AL-Shudeifat, M. A. A review on nonlinear energy sinks: designs, analysis and applications of impact and rotary types. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 1–37 (2023).

Felix, J. L. P., Balthazar, J. M. & Dantas, M. J. H. On energy pumping, synchronization and beat phenomenon in a nonideal structure coupled to an essentially nonlinear oscillator. Nonlinear Dyn. 56, 1–11 (2009).

Georgiades, F. & Vakakis, A. F. Dynamics of a linear beam with an attached local nonlinear energy sink. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numeri. Simul. 12, 643–651 (2007).

Ahmadabadi, Z. N. & Khadem, S. E. Nonlinear vibration control of a cantilever beam by a nonlinear energy sink. Mech. Mach. Theory 50, 134–149 (2012).

Kani, M., Khadem, S. E., Pashaei, M. H. & Dardel, M. Design and performance analysis of a nonlinear energy sink attached to a beam with different support conditions. Proc. Institut. Mech. Eng., Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 230(4), 527–542 (2015).

Kani, M., Khadem, S. E., Pashaei, M. H. & Dardel, M. Vibration control of a nonlinear beam with a nonlinear energy sink. Nonlinear Dyn. 83, 1–22 (2016).

Felix, J. L. P. & Brasil, R. M. L. R. F. A nonlinear electromechanical pendulum arm with a nonlinear energy sink control (NES) approach. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 54(3), 975–986 (2016).

Chen, J. E. et al. Vibration suppression and higher branch responses of beam with parallel nonlinear energy sinks. Nonlinear Dyn. 91, 885–904 (2018).

Moslemi, A., Khadem, S. E., Khazaee, M. & Davarpanah, A. Nonlinear vibration and dynamic stability analysis of an axially moving beam with a nonlinear energy sink. Nonlinear Dyn. 104, 1955–1972 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Ding, H., Zhang, Y. W. & Chen, L. Q. Vibration suppression of an elastic beam with boundary inerter-enhanced nonlinear energy sinks. Acta Mechanica Sinica 37(3), 387–401 (2021).

Zhang, Z., Gao, Z. T., Fang, B. & Zhang, Y. W. Vibration suppression of a geometrically nonlinear beam with boundary inertial nonlinear energy sinks. Nonlinear Dyn. 109, 1259–1275 (2022).

He, M. X., Tang, Y. & Ding, Q. Dynamic analysis and optimization of a cantilevered beam with both the acoustic black hole and the nonlinear energy sink. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 33(1), 70–83 (2022).

Zhao, Y., Du, J., Chen, Y. & Liu, Y. Comparison study of the dynamic behavior of a generally restrained beam structure attached with two types of nonlinear vibration absorbers. J. Vib. Control 29(19–20), 4550–4565 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Du, J. & Liu, Y. Vibration suppression and dynamic behavior analysis of an axially loaded beam with NES and nonlinear elastic supports. J. Vib. Control 29(3–4), 844–857 (2023).

Zhao, Y., Guo, F., Sun, Y. & Shi, Q. Modeling and vibration analyzing of a double-beam system with a coupling nonlinear energy sink. Nonlinear Dyn. 112, 9043–9061 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Cui, H., Shi, Q. & Sun, Y. A study of controlling the transverse vibration of a beam-plate system by utilizing a nonlinear coupling oscillator. Thin-Walled Struct. 200, 111903 (2024).

Chen, M., Zhao, Y., Guo, R. & Tao, P. The vibroacoustic study of a plate-cavity system with connecting nonlinear oscillators. Thin-Walled Struct. 204, 112317 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Du, J., Chen, Y. & Liu, Y. Nonlinear dynamic behavior analysis of an elastically restrained double-beam connected through a mass-spring system that is nonlinear. Nonlinear Dyn. 111, 8947–8971 (2023).

Zhao, Y. & Xu, D. Dynamic analysis of a plate system coupled through several nonlinear spring-mass couplers. Thin-Walled Struct. 196, 111490 (2024).

Ding, H. & Shao, Y. NES Cell. Appl. Math. Mech. 43, 1793–1804 (2022).

Qingchuan Zhan, Yilin Chen, Yuhao Zhao, Mingfei Chen & Rongshen Guo. Vibration suppressing study of a simplified floating raft system by mixing using a nonlinear connecting intercalary plate and connecting nonlinear oscillators., 112686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tws.2024.112686 (2024).

Zheng, H. T., Mao, X. Y., Ding, H. & Chen, L. Q. Distributed control of a plate platform by NES-cells. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 209, 111128 (2024).

Tusset, A. M. et al. Non-linear energy sink applied in the vibration suppression of a high-speed elevator system and energy harvesting. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 11, 2819–2830 (2023).

Tusset, A. M. et al. Dynamic analysis and energy harvesting of a portal frame that contains smart materials and nonlinear electromagnetic energy sink. Arch. Appl. Mech. 94, 2019–2038 (2024).

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52205091) and Guizhou Provincial Key Technology R&D Program (QKHZC[2023]General 338).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.C. and S.L. wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all the figures. M.C. wrote the revised manuscript and the reply letter. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, M., Li, S. & Cui, H. Longitudinal dynamic behavior study of a vibrating rod connected through an elastic nonlinear single degree freedom coupler. Sci Rep 14, 27326 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78762-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78762-z