Abstract

Highly accurate nighttime cloud detection in satellite imagery is challenging due to the absence of visible to near-infrared (0.38–3 μm, VNI) data, which is critical for distinguishing clouds from other ground features. Fortunately, Machine learning (ML) techniques can more effectively leverage the limited wavelength information and show high-accuracy cloud detection based on vast sample volume. However, accurately distinguishing cloud pixels solely through thermal infrared bands (8–14 μm, TIR) is challenging, and acquiring numerous, high-quality and representative samples of nighttime images for ML proves to be unattainable in practice. Given the thermal infrared radiation transmission process and the fact that daytime and nighttime have the same source of radiance in TIR, we propose a sample generation idea that uses daytime images to provide samples of nighttime cloud detection, which is different from the traditional sample construction methods (e.g., manually label, simulation and transfer learning method), and can obtain samples effectively. Based on this idea, nighttime cloud detection experiments were carried out for MODIS, GF-5 (02) and Himawari-8 satellites, respectively. The results were validated by the Lidar cloud product and manual labels and show that our nighttime cloud detection result has higher accuracy than MYD35 (78.17%) and the ML model trained by nighttime manual labels (75.86%). The accuracy of the three sensors is 82.19%, 88.71%, and 79.34%, respectively. Moreover, we validated and discussed the performance of our algorithm on various surface types (vegetation, urban, barren and water). The results revealed that the accuracy of the three sensors over barren was found to be poor and varied with surface types but overall high. Our study can provide a novel perspective on nighttime cloud detection of muti-spectral satellite imagery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Clouds cover approximately 67% of the Earth’s surface, with about 55% of cloud cover over land and approximately 72% over the ocean1. The presence of clouds can block the sunlight, and the extent of cloud cover can have varying effects on the transmission of radiation and the energy balance of the Earth2,3. Furthermore, clouds can affect the process of obtaining atmospheric and surface parameters by satellite sensors during the day and night, leading to significant uncertainties in retrieving atmospheric and surface characteristics4,5. Accurate cloud detection is essential for improving remote sensing and understanding the impact of clouds on climate.

Spectrum threshold (ST) based methods and the Machine learning (ML) based methods are the primary techniques for cloud detection in satellite imagery. The ST-based methods usually use the top-of-atmosphere (TOA) reflectance difference between clouds and typical surface features in visible to near-infrared (VNI), and the brightness temperature (BT) difference in TIR to set the appropriate thresholds to achieve high-precision detection of cloud pixels. The typical ST-based methods mainly include the International Satellite Cloud Climatology Project (ISCCP)6,7, AVHRR Processing scheme Over cLouds, Land, and Ocean (APOLLO)8,9, Clouds from the Advanced Very high Resolution Radiometer (CLAVR)10, CO2 slicing cloud mask algorithm11,12 and the most commonly used for Landsat satellites method (Fmask)13,14. Since there are fewer infrared channels compared to visible channels in the configuration of optical sensors, developing a nighttime cloud detection algorithm is more challenging15. For MODIS, nighttime cloud detection primarily involves determining thresholds through brightness temperature and their differences in the thermal infrared band, such as brightness at 6.7 μm, 11 μm, and 13.9 μm for nighttime ocean and land16. The Himawari-8 Cloud Mask Product (CMP) for nighttime utilizes brightness temperature at 10.4 μm, and the difference between 10.4 μm and 3.9 μm to identify cloud and clear pixels at night17.

Due to their simplicity and cost-effectiveness, cloud detection algorithms based on ST have gained widespread adoption across various satellite sensors and have demonstrated excellent performance. However, these algorithms are typically tailored for specific sensors, meaning that the cloud detection thresholds may vary among different sensors. Consequently, these algorithms may lack versatility and face challenges in significantly enhancing their cloud detection accuracy. Fortunately, the introduction of ML-based cloud detection methods has provided a new perspective for cloud detection on the satellite imagery, which integrate spectral, textural, and structural features to achieve high-accuracy cloud detection18,19. Due to its powerful information extraction ability and nonlinear modeling, it can excavate the limited channel information to a greater extent and achieve higher precision cloud detection20,21. ML models such as Random Forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) and convolutional neural networks (CNN) have been extensively used in cloud detection and have shown excellent performance22,23,24.

Both the ST-based and ML-based methods use the TOA difference between the cloud and the typical surface features in the VNI bands and the BT difference in the TIR bands to detect clouds. The significant disparity in reflection characteristics between clouds and typical surface features in the VNI bands makes these bands crucial for cloud detection; satellite sensors widely utilize them as the primary channels for accurate cloud detection. However, high-accuracy cloud detection in nighttime images poses significant challenges due to the absence of VNI bands. For the ML methods, acquiring high-quality and diverse samples is crucial to achieve accurate cloud detection. The availability of representative and comprehensive training data plays a fundamental role in training ML models that can effectively detect clouds with high precision. Artificial identification is considered the most essential approach for obtaining high-quality samples25,26. However, interpreting nighttime satellite images visually proves difficult due to the lack of VNI information, which means that only the TIR band can be relied upon for the artificial identification of cloud samples. A large number of low-temperature targets introduces uncertainty and error in the manually recognized cloud samples, leading to more significant limitations on the reliability of these samples, which affects the accuracy of cloud detection by ML techniques.

To mitigate the difficulties in sample acquisition at night, the method of constructing an optical- LiDAR paired dataset is introduced21,23,27. However, LiDAR satellites have limitations in terms of their temporal and spatial resolutions, preventing them from achieving large-scale continuous observations23. Consequently, the insufficient quantity and diversity of nighttime samples is the primary factor leading to the currently low accuracy of ML-based nighttime cloud detection methods. To overcome this challenge, we propose an ML sample generation method that is based on the fact that daytime and nighttime have the same source of radiance in TIR and leverages daytime images with brightness temperature (BT) in the 8–14 μm thermal infrared range as inputs for training a ML model designed for nighttime cloud detection. The sample generation method is grounded in the atmospheric radiative transfer principles, which indicate consistent BT characteristics for clouds during day and night, allowing daytime TIR data to inform nighttime detection practices. Daytime imagery permits better visual interpretation due to the presence of both TIR and VNI information, facilitating the identification of cloud and non-cloud samples. By utilizing the information available from daytime imagery, we aim to overcome the limitations posed by the scarcity of nighttime training samples and enhance the performance of cloud detection ML models during nighttime conditions. We compared four widely used ML models, Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), LightGBM (LGB), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), based on visual interpretations of daytime imagery from GF-5(02) satellite data. Among these, LGB exhibited the best overall performance and was selected to conduct cloud detection on MODIS (Aqua), GF-5(02), and Himawari-8 satellite data. Finally, three types of satellite data were validated and compared during both daytime and nighttime for four different underlying land covers: vegetation, urban, barren and water. A successful application was considered when the results reached 80% or higher accuracy. This threshold was selected based on the performance of MODIS, one of the widely used optical sensors for Earth observation, which is critical for climate change research and environmental monitoring. While MODIS delivers reliable cloud detection results with its operational cloud mask, its nighttime cloud mask typically performs below 80% accuracy in most cases16, making this value a reasonable benchmark for our study.

Theory and principles

In the VNI(0.38–3 μm), assuming a homogenous atmospheric layer and a Lambertian surface, Eq. (1) can be used to express the total radiation received by the satellite sensors28:

where \(\:{L}_{i}\) is the total radiation received by the sensor, \(\:{L}_{R+A}\) is the atmospheric radiance from Rayleigh scattering and aerosol scattering, \(\:{\theta\:}_{\text{s}}\) is the solar zenith angle, \(\:{\theta\:}_{\text{v}}\) is the sensor zenith angle, \(\:\phi\:\) is the relative azimuth angle, \(\:S\) is the spherical albedo of the atmosphere, \(\:{\rho\:}_{s}\) is the surface reflectance, \(\:{T}_{\lambda\:}^{\downarrow\:}\left({\theta\:}_{\text{s}}\right)\) represent the downwelling transmittance from the sun to the surface and \(\:{T}_{\lambda\:}^{\uparrow\:}\left({\theta\:}_{\text{v}}\right)\) represent the upwelling transmittance from the surface to the sensor, \(\:{E}_{s}\) is the solar flux at the top of the atmosphere, and \(\:{L}_{sun,\lambda\:}={E}_{s}\text{c}\text{o}\text{s}\left({\theta\:}_{\text{s}}\right)\), which is the solar radiance at the top of the atmosphere.

In the middle wave infrared (3–5 μm, MWIR), the signal received by the satellite in MWIR can be computed as29:

where \(\:{L}_{i}\) is the total radiation received by the sensor in band \(\:i\), \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\lambda\:}\) is the surface specific emissivity, \(\:{B}_{\lambda\:}\left({T}_{s}\right)\) is the blackbody radiation calculate by Planck function at a temperature of \(\:T\), \(\:{\rho\:}_{s}\) is the surface reflectance, \(\:{L}_{sun,\lambda\:}\) is the solar radiance at the top of the atmosphere, \(\:{\tau\:}_{\lambda\:}\) is the atmospheric transmittance, \(\:{L}_{\lambda\:}^{\downarrow\:}\) and \(\:{L}_{\lambda\:}^{\uparrow\:}\) represent the upwelling and downwelling radiance, \(\:\theta\:\) is the zenith angle of the sensor. The first term on the right side is the surface emitted radiation. The second term is the solar radiation that reaches the sensor after reflection from the surface. The third term is the radiation reaching the sensor after the atmospheric downward radiation is reflected by the surface, and the fourth term is the upward atmospheric radiation.

The signal received by satellite sensors in the TIR(8–14 μm) can be computed by the Eq. (3) based on the radiative transfer theory30,31.

where \(\:{L}_{i}\) is the total radiation received by the sensor, \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{\lambda\:}\) is the surface specific emissivity, \(\:{B}_{\lambda\:}\left({T}_{s}\right)\) is the blackbody radiation calculate by Planck function at a temperature of \(\:T\), \(\:{\tau\:}_{\lambda\:}\) is the atmospheric transmittance, \(\:{L}_{\lambda\:}^{\downarrow\:}\) and \(\:{L}_{\lambda\:}^{\uparrow\:}\) represent the upwelling and downwelling radiance, \(\:\theta\:\) is the zenith angle of the sensor. On the right side of Eq. (3), the first term is the radiation emitted from surface. The second term is downward radiation reflected by the surface and the third term is the upward atmospheric radiation.

From Eqs. (1) and (2), the radiance received by the sensor in the VNI and MWIR bands is influenced by solar radiation. Consequently, during nighttime, when solar radiation is absent, the radiance captured by the sensor significantly differs from that observed during the daytime. However, in the TIR band, as described in Eq. (3), the energy detected by the satellite sensor originates solely from the ground surface, independent of solar radiation. This allows us to consider that the sources of radiant energy for satellite sensors in the TIR band are consistent between daytime and nighttime. Therefore, daytime TIR images can be analyzed with the assumption that they share similar radiation characteristics with nighttime images. Thus, in this paper, we propose to use daytime images to provide high-quality sample information for nighttime thermal infrared images to support ML techniques to achieve high-precision cloud detection for nighttime images.

Methods

Geographical map of the study region, accompanied by a detailed distribution of diverse surface types, with land surface type data sourced from MCD12.The maps were created using ESRI ArcGIS Pro 3.0.0 (https://www.esri.com).

The study was conducted in East Asia (Fig. 1), utilizing datasets acquired by three satellites: GF-5 (VIMI), Aqua (MODIS), and Himawari-8 (AHI), to demonstrate our methodology. These datasets encompass imagery from different seasons throughout 2022, featuring a diverse array of surface types. Training datasets were collected randomly and evenly, distributed by date and location, with clear and cloudy pixels selected separately. As illustrated in Fig. 1, surface types were identified using MCD12 as a reference. Local nighttime images were obtained based on the UTC time (16:00–21:00) of satellite transit. In terms of their satellite orbit, GF-5 and Aqua are polar-orbiting satellites, which means they orbit the Earth from pole to pole, providing global coverage over time. On the other hand, Himawari-8 is a geostationary satellite, which means it orbits the Earth at the same rate as the Earth’s rotation, allowing it to remain fixed relative to a point on the Earth’s surface. These two kinds of orbits are commonly utilized for meteorological satellites, navigation satellites, Earth resource satellites, and other applications that require global-scale observation.

In addition, these three satellites have resolutions of 40 m, 1 km and 5 km, respectively, covering the characteristics of satellite data with high, medium and low spatial resolutions. The satellites are equipped with VIMI (GF-5), MODIS (Aqua), and AHI (Himawari-8) sensors, covering a wide range of spectral bands, including VNI (0.38–3 μm), MWIR(3–5 μm) and TIR(8–14 μm). TIR bands enable nighttime imaging, as they can detect thermal radiation emitted by objects. Besides, the band range of TIR is divided into multiple channels, which makes it easier for band selection and experimental verification. For that, the selection of the three satellite datasets GF-5, MODIS, and Himawari-8 is representative and more widely applicable to the experimental validation of the cloud detection algorithm for nighttime images we proposed. The results were validated by Lidar cloud products and manual labels25,32. Also, they were compared to the operational MYD35 product for MODIS (Aqua) and the CLP product for Himawari-8 (AHI), as well as to a model trained with nighttime manual labels. Specific descriptions of the above data in this study are provided in Text S1. Detailed spectral information of used satellite sensors, i.e., VIMI, MODIS and AHI, is shown in Table S1. Overall, these selected satellite data products are comprehensive and appropriate, effectively avoiding potential bias and enhancing the reliability of our sample generation algorithm.

Sample generation method

In cloud detection research, it is common practice to utilize manually labelled samples for training ML models22. Based on atmospheric radiative transfer theory33, during the daytime, optical satellite sensors primarily receive information from the reflected solar radiation. They capture images in the visible and near-infrared wavelength range of 0.38–3 μm, which contain abundant ground object information and are easily interpreted visually, allowing for accurate sample labelling. However, during nighttime, satellite sensors mainly receive information from the thermal radiation emitted by ground objects, imaging in the thermal infrared wavelength range of 3–14 μm. Due to the absence of visible light (0.38–0.76 μm) information, the visual interpretation of nighttime images is less effective, which poses challenges in ensuring the quality of sample construction.

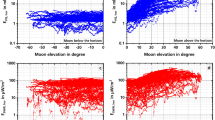

By analyzing the equation of MWIR and TIR, we gain a clear understanding of the interaction mechanism of solar radiation with the atmosphere and the Earth’s surface. From Eq. (3), it is evident that ground objects barely reflect solar radiation in the TIR band, allowing us to ignore the second term from Eq. (2) during the daytime. Simultaneously, the reflective component is negligible across all thermal infrared bands due to the absence of solar radiation at night, with surface emission contributing the majority of the radiation energy. Figure 2 shows the distribution of daytime and nighttime cloud samples between MWIR and TIR. We randomly selected 5,000 cloud samples during both day and night. According to the normal distribution criterion, the histogram of sample distribution was statistically analyzed and plotted. The x-axis represents the brightness temperature range of randomly selected samples, while the y-axis represents the distribution frequency of data points within that range. From the figure, it is clear that the cloud brightness temperature (BT) of night and day is significantly differing in MWIR, with the daytime cloud sample distribution tending towards a higher BT range due to solar radiation, especially at 3.75 μm (Fig. 2a). Although the number of samples may vary significantly due to factors such as surface type and solar radiation, the overlapping areas of the two histograms indicate that the difference between day and night samples narrows with increasing wavelength.

For the TIR, the BT distribution of daytime and nighttime samples is consistent, and the daytime scene adequately represents the nighttime situation. Considering that the introduction of MWIR may lead to errors and that MWIR information is not essential for identifying clouds and other ground objects, the daytime MWIR of different sensors was not used as sample sources in this study. Consequently, we propose an innovative sample generation algorithm for nighttime cloud detection that utilizes daytime samples acquired by satellite sensors capable of capturing TIR information and applies them to train ML models for nighttime cloud detection.

During the daytime, we validated our method using operational cloud masks from MODIS and Himawari-8 satellites. As there was no cloud product available for GF5(02) data, we employed manually interpreted labels for validation. The effectiveness and feasibility of our method were confirmed when the results corresponded to those obtained through operational cloud products. During the nighttime, we utilized manually annotated samples and CALIPSO lidar data as ground truth to compute the accuracy of the proposed algorithm for nighttime cloud detection.

Models selection

To select an appropriate ML model for the validation of our proposed algorithm, we employed Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN), LightGBM (LGB), Random Forest (RF), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). GF-5(02) as the sensor with the highest spatial resolution for straightforward visual interpretation in our study, we relied on the manual labels for model selection and utilized our approach to predict and validate the results for both daytime and nighttime images of GF5, as elaborated in the Test S2. Figure S1 illustrates the cloud detection performance of four ML models on different surface types and the specific performance is shown in Fig. S2.

(1) FCNN is a specific type of Deep Neural Network structure in which each node has an operational relationship with all the nodes in the upper and lower layers34. It consists of a multi-layer perceptron that can be used to identify the most reasonable and robust hyperplane between different classes35. The network structure of FCNN is mainly composed of input layers, hidden layers and output layers36.

(2) The LGB model is an improvement upon the Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT) algorithm and can speed up the training of the GBDT model without compromising accuracy. The improvement in training speed is mainly achieved by utilizing two algorithms: Gradient-based One-Side Sampling (GOSS) and Exclusive Feature Bundling (EFB).

(3) The RF model classifier is an ensemble classifier and is popular in remote sensing for classification accuracy37. During the training process, it randomly selects training samples and feature variables, which effectively prevents overfitting. Additionally, RF has a simple structure and is easy to use, as it can obtain better results in most cases even without hyperparameter tuning.

(4) Like the LGB model, the basic idea of XGBoost originates from GBDT, but it incorporates several optimizations on top of it. XGBoost employs second-order derivatives to make the loss function more precise, effectively constructing boosted trees (regression and classification trees) and running parallel computation38. Furthermore, to address overfitting, it adopts a more regularized model formulation and employs hyperparameter tuning similar to Random Forest39.

These models have been widely applied in atmospheric, parameter retrieval and other fields22,39,40,41. The net structure and parameters used by FCNN refer to this article42. LGB, RF and XGBoost used the default parameters of the Sklearn library in the Python platform. Overall, our models were selected based on GF5(02) data and the manually labelled samples were utilized to validate and compare the cloud detection accuracy of these models for various underlying surface types (Figure S3, Table S2), further explanations and analyses are in Text S3. Considering the cloud detection accuracy and visual performance of the models on the different underlying surface types, LGB was selected as the ML model for our algorithm development and verification. Note that LGB was only used to verify the feasibility and potential of the algorithm in nighttime cloud detection and the improvement of cloud detection accuracy of the model needs further work.

Models construction

To prove the adaptability of the algorithm on different types of satellite sensors, the data obtained from three satellite platforms, GF-5(02), MODIS(Aqua) and Himawari-8, were used for training and validation of the LGB model. Considering the spectral characteristics and spatial resolution of different satellite sensors, BT in the TIR band were selected as input feature for the model and detailed information for three satellite sensors is provided in Table 1.

To evaluate our proposed method, two LGB models were established for GF-5(02), one was the nighttime model established by using the labels labeled at night, and the other was the daytime model established by using the samples labelled during the day. MYD35_L2 and CLP_L2 are the operational cloud products provided by MODIS (Aqua) and Himawari-8, respectively. These products perform well in daytime cloud detection and have been in operation for several years43,44,45,46. Consequently, these two cloud products, MYD35_L2 and CLP_L2, served as the reference data sources for MODIS (Aqua) and Himawari-8. Since MYD35_L2 and CLP_L2 are multi-level cloud masks (including cloudy, uncertain clear (probably cloudy for CLP_L2), probably clear, and clear), we considered that “uncertain clear (probably cloudy)” in MYD35 and CLP_L2 encompasses a broader range of cloud types, such as thin and broken clouds, and that “probably clear” may also include diverse surface conditions. To ensure comprehensive coverage of clouds and surface conditions, the cloudy and uncertain clear (cloudy and probably cloudy) are taken as cloudy, and the probably clear and clear (probably clear and clear) are taken as clear for the MODIS (Aqua) (Himawari-8) when building the reference cloud labels47,48. As there are no operational cloud detection products available for GF-5 (02), the reference data was obtained by labelling false color images. 80% of the data in the samples was used for model training and 20% was used for model validation to prevent model overfitting during training. The detailed information for constructing the sample dataset is presented in Table 1. Figures S4-S6 provide detailed histograms of the sample distributions. Since we use brightness temperature as an input feature, the x-axis represents the range of brightness temperatures (200–350 K) within the samples, and the y-axis indicates the number of samples.

The Sklearn library in Python was used to build the four LGB models and the optimal parameters (n_estimator, max_depth and learn rate) of the models were determined by the iterative method23. Figure 3 clearly illustrates the accuracy of cloud detection for the four models under different parameters. Note that the ranges of these parameters were set to encompass typical scenarios. From the figure, it is evident that different models have distinct optimal parameters. Specifically, for MYD_LGB, the optimal parameters are 400, 12 and 0.09 for estimator, max depth and learn rate, respectively. For GF_LGB_Day, the optimal parameters are 400, 12, and 0.17. GF_LGB_Night has the optimal parameters 400, 8, 0.01. Lastly, for HMW_LGB, the optimal parameters are 400, 12 and0.17.

Feature evaluation

To better evaluate the training results and identify key features captured by the model, we employ the SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations)49 unified framework for interpreting predictions. This approach assigns an importance value to each feature for a specific prediction, enhancing our understanding of the model’s decision-making process. The calculation of SHAP values is illustrated in Eq. (4).

where \(\:{\varphi\:}_{i}\left(x\right)\) represents the SHAP value of feature \(\:i\) for instance \(\:x\); \(\:{x}_{S}\) denotes the value of the subset of features excluding feature \(\:i\); \(\:f\) is the prediction function of the model, and \(\:F\) is the total number of features.

We sorted the feature importance of the three satellite datasets, as shown in Fig. 4. In Fig. 4a, for GF5 (VIMI), the B12 band (11.4–12.5 μm) is clearly the most important feature. In Fig. 4b, for Himawari-8 (AHI), the B14 band (11.2 μm) ranks highest in importance. Similarly, in Fig. 4c, for Aqua (MODIS), the B32 band (11.7–12.2 μm) is identified as the most important feature. Since 11–12 μm is the atmospheric window, the atmosphere has minimal effect on the absorption, reflection, and scattering of radiation energy, allowing it to penetrate more effectively. Consequently, the presence of clouds in remote sensing images significantly alters the radiation energy received by the sensor. This can help further improve cloud detection through physical means.

Results and discussion

Given the limitations of visual interpretation of satellite imagery at night, our algorithms were first tested for performance across various surface types during daytime. Due to only the TIR bands being used for cloud detection, our models can be simultaneously applied for daytime and nighttime imagery. Despite this, the results in daytime imagery are not very accurate compared to that of cloud detection algorithms designed for daytime imagery, due to our lack of VIR. Thus, we perform daytime cloud detection to prove the validity of our models rather than high-accuracy daytime cloud detection since we aim to improve nighttime cloud detection. After this, the nighttime cloud detection results were quantitatively verified using the CALVFM datasets.

Validation of daytime cloud detection results

Our algorithm relies exclusively on thermal infrared (TIR) data, which remains unaffected by sunlight interference. Since TIR radiation emitted from the surface is available around the clock, the algorithm is capable of detecting clouds both during the day and at night. Besides, as the models were trained using daytime samples, the feasibility and potential of utilizing solely thermal infrared bands for cloud detection in spectral data can be demonstrated by validating the results of daytime cloud detection. Finally, the data for daytime validation are completely independent of the training sample data shown in Table 1, but from the images obtained at other times50,51, which can be used to effectively test whether the LGB models are effectively trained and its cloud detection capability in real situations. Note that different sensors utilize distinct cloud label sources as validation reference data for their respective models. Specifically, in the case of MYD_LGB, MOD35 serves as the validation data. For GF_LGB_Day, validation data is derived from manual labels. HMW_LGB utilizes CLP_L2 as the validation data. To quantitatively evaluate the accuracy of cloud detection, we utilized the cloud or clear sky hit rate (CHR), false alarm rate (FAR), and overall accuracy metrics. These metrics can be calculated using the following Eqs23,52:

where \(\:{Reference}_{cld}\) and \(\:{Reference}_{clr}\) are the number of cloudy and clear sky pixel samples of the reference data, \(\:{Prediction}_{cld}\) and \(\:{Prediction}_{clr}\) represent the number of cloudy and clear sky pixel samples of the reference data, respectively; \(\:\&\) indicates the pixels in agreement. Note that These processes may introduce biases in evaluating cloud detection accuracy to some extent23.

MODIS(Aqua)

The cloudy sky and clear sky cloud detection statistics on the different underlying surface types (vegetable, urban, barren and water) are shown in Table 2, respectively. On the whole, MODIS (Aqua) demonstrates excellent performance in daytime cloud detection, achieving an accuracy rate of 82.38%. Compared to other underlying surface types, the overall accuracy of cloud detection in urban areas is the highest (91.94%), and the clear sky has the highest CHR (94.41%) and the lowest FAR (0.0559). However, the performance of its CHR and FAR is suboptimal under cloudy sky conditions and the number of urban pixels involved in the accuracy validation (7116 for cloudy sky and 20588 for clear sky) is significantly lower compared to other surface types. The cloud detection accuracy and overall accuracy on vegetation (86.26%) and water (77.44%) surface types are comparable. The CHR and FAR also indicate that the performance of cloud detection under these two surface types is in the middle level. The cloud detection accuracy on barren is the lowest (73.87%) due to its poor performance under clear sky conditions. However, under Cloudy sky conditions, it can achieve the highest cloud hit rate (89.93%) and the lowest false alarm rate (10.07%).

Figure S7 illustrates the cloud detection results of MODIS (Aqua) for the entire image during three periods in 2022, showing relatively good visualization effects. Generally, the cloud detection results exhibit a high level of consistency with the reference image (MYD35_L2). This indicates that the identified cloud changes and spatial distribution are in agreement between the two, aligning with the overall accuracy validation presented in Table 2, which exceeds 80%. Regarding the July image (Figure S7 (i)), which encompasses numerous mountainous regions, the detection of thin clouds in these areas is not successful. This is evident in Figure S7 (i), where a red circle highlights a noticeable cloud omission. The limitation arises from the fact that the model solely relies on TIR spectral data captured by the sensor. Within this wavelength range, the BT of thin clouds is influenced (increased) by the underlying surface, making it challenging to distinguish between the thin cloud and other low-temperature ground objects (such as shadows). As a result, the similar thermal infrared characteristics of thin clouds and these ground objects further complicate cloud identification. Similar to the aforementioned reasons, the cloud detection results for September exhibit noticeable omissions in the broken cloud areas (Figure S7 (iii)). Fortunately, considering additional features such as the Digital Elevation Model (DEM), contextual information and classification data can effectively alleviate the challenges associated with identifying thin clouds and broken clouds on remote sensing images53. We focus on verifying the feasibility of utilizing daytime thermal infrared samples for nighttime cloud detection in the paper and the application of this theory for higher-precision nighttime cloud detection will be our future endeavor.

Himawari-8

The cloudy sky and clear sky cloud detection statistics on the different underlying surfaces (vegetable, urban, barren and water) from Himawari-8 daytime images are shown in Table 3, respectively. In general, the overall accuracy of cloud detection (80.59%) is over 80% and similar to that of MODIS(Aqua) and GF-5 (02), which means the method proposed in the paper, daytime samples applied to nighttime cloud detection, has the potential and ability to be used for different satellite sensors. However, the performance of cloud detection is completely different in different sky conditions. For cloudy sky conditions, the CHR is up to 98.19% and the FAR is low to 1.81%, meaning that HMW_LGB has excellent performance in the presence of clouds. On the contrary, the CHR and FAR of clear sky are 9.79% and 90.24%, respectively, which proves that the cloud detection performance of the model is poor under clear sky conditions. From Figures S5 and S6, we observe significant differences between the sample distributions of MODIS and Himawari-8. Compared to MODIS, Himawari-8 has a smaller proportion of clear sky pixels and more overlap with cloud pixels. This uneven sample distribution may lead to insufficient model training, causing the model to fail under clear-sky conditions. A well-designed sample distribution can effectively alleviate this problem. The primary focus of this paper is not on the accuracy during the daytime, but rather on the adaptability and potential of the method during the nighttime. This is further illustrated in conjunction with our accuracy statistics for the night as presented in Table 4.

Figure S8 illustrates the daytime cloud detection results of Himawari-8 for the entire image during three different periods in 2022. Since Himawari-8 is a geostationary satellite imaging of the same location of the earth, the three images of different periods contain the same surface types. The map size of Himawari-8 imaging (about 6000–7000 km) is much larger than that of MODIS (Aqua) (2330 km) and GF-5(02) (800 km), which includes the entire East Asian region. Therefore, most of the areas on the Himawari-8 are covered by clouds as shown in Figure S8 (i), which is also the reason for the large number of clouds in the samples we constructed. Generally, the results of the HMW_LGB are highly consistent with those of the reference images (CLP_L2) in terms of similar spatial changes. However, the cloud results obtained from HMW_LGB are continuously compared to the more discrete clouds of CLP_L2, meaning cloud omission of HMW_LGB. The performance of the HMW_LGB model is poor under clear sky conditions, as indicated by the red circles in Figure S8, while it performs well in areas with clouds. The uneven distribution of samples, specifically the scarcity of clear sky samples, is the cause of this problem. This situation is analogous to the issues encountered in MYD_LGB and GF_LGB_Day, where an abundance of clear sky samples posed challenges.

Validation of nighttime cloud detection results

To validate and compare the performance of our algorithm at night, the models (MYD_LGB, GF_LGB_Day and HMW_LGB) were applied to the nighttime images of corresponding sensors and the results were validated by the lidar vertical feature mask data (VFM) of CALIPSO and compared with operational cloud products or nighttime model. The limited range and sparse data records of GF-5(02) make it challenging to locate matching nighttime data of GF-5(02) and VFM in both time and space. Therefore, the result of GF-5(02) was validated by manual labels. The overall accuracy (OA), precision, recall and F1 were used to quantitatively validate the nighttime cloud detection results of MODIS(Aqua), GF-5(02) and Himawari-8. These accuracy metrics can be calculated by following Eqs. (10–13) and their results are shown in Table 4.

where TP, TN, FP and FN represent the true positive, true negative, false positive and false negative, respectfully. The F1 is a measure of the similarity between precision and recall.

For MODIS(Aqua), the nighttime cloud detection results of MYD_LGB_Day are better than that of MYD35_L2 given 6427 matching points, since MYD_LGB_Day shows higher OA (0.8219), precision (0.8929), recall (0.8032) and F1(0.8426) compared to those of the operational cloud product (OA = 07817, precision = 0.8839, recall = 0.7678 and F1 = 0.8131). As for GF-5(02), a total of 87,461 matching points were found to validate the cloud detection results of the GF_LGB_Day and GF_LGB_Night. The OA (0.8871), precision (0.8562), recall (0.9962) and F1(0.9182) of GF_LGB_Day is about 10% higher than those of the model trained by night samples with OA = 0.7580, precision = 0.7426, recall = 0.9411 and F1 = 0.8137, which is proved that GF_LGB_Day outperforms GF_LGB_Night in nighttime cloud detection. For the geostationary satellite, only the 35,352 results of HMW_LGB were validated by the VFM due to the operational cloud product (CLP_L2) lacking night data. The statistics data from Table 4 shows that the HMW_LGB is very suitable for cloud detection of Himawari-8 nighttime images, along with high accuracy metrics ranging from 0.7934 to 0.9505. The best metric is the recall, and the worst is the OA. The values of the precision and F1 are 0.8241 and 0.9505, respectively. Overall, our algorithm that uses samples of the daytime thermal infrared band to train ML models for nighttime cloud detection is better than the operational cloud products and the traditional model trained by the samples at night and have obtained good cloud detection results for different satellite sensors (MODIS(Aqua), GF-5(02) and Himawari-8).

To enhance the comprehension of the model’s performance and to assess its proficiency in discriminating between cloudy and clear skies, this study employs MODIS as a benchmark for comparison. CHR and FAR of cloud detection for both the proposed methodology and the operational MODIS product are contrasted. As delineated in Table 5, the results indicate that for clear skies, the performance MYD_LGB_Day is on par with MYD35_L2. However, in the context of cloudy skies, MYD_LGB_Day demonstrates a higher CHR of 0.8032 compared to 0.7678 for MYD35_L2, alongside a lower FAR of 0.1968 as opposed to 0.2321 for MYD35_L2. These results are consistent with the statistical precision results in Table 4, further affirming the reliability of the findings previously discussed in conjunction with Table 4.

Conclusion

In this study, we propose a cloud detection sample generation method that uses the daytime TIR information in the range of 8–14 μm to construct samples for nighttime cloud detection. To verify the applicability of this method, data from three satellite sensors were used to construct samples using the method and were applied to train ML models. The optimal model was used for cloud detection of different sensors and their results were compared and validated by different reference data. The daytime validation results show that the overall accuracy of cloud detection with different sensors is above 80%, which proves the adaptability of the algorithm to different sensors. Furthermore, there are obvious differences in cloud detection performance between cloudy and clear sky conditions. Among them, MYD_LGB and GF_LGB_Day exhibit better performance under cloudy sky conditions compared to clear sky conditions. In contrast, HMW_LGB performs poorly under cloudy sky conditions. This disparity can be attributed to the uneven distribution of clear sky and cloud pixels in the samples. From the nighttime results, the cloud detection overall accuracy, precision, recall and F1 of our proposed algorithm on different sensors are all above 80% except for the accuracy of HMW_LGB (0.7934). In addition, the cloud detection results of MYD_LGB are better than that of MYD35_L2, which means that the proposed algorithm can be used for nighttime cloud detection of MODIS(Aqua) images. The cloud detection accuracy of GF_LGB_Day is higher than that of GF_LGB_Night, which proves that the proposed algorithm can solve the problem of low accuracy of labelling samples using nighttime images, to improve the accuracy of nighttime cloud detection. Due to its high accuracy and the absence of operational cloud detection products for Himawari-8, HMW_LGB can be directly utilized for nighttime cloud detection on Himawari-8.

Overall, we provide evidence of the nighttime cloud detection sample generation algorithm’s advantages, adaptability, and potential for further improvement. In our upcoming work, our objective is to use our algorithm to create a more balanced and ample set of samples for a specific sensor, such as MODIS (Aqua), to enhance the robustness of model training for improved accuracy in nighttime cloud detection. The samples generated by our algorithm have been proved to effectively train machine learning models for nighttime cloud detection across different satellite sensors. Our study can provide a novel perspective on nighttime cloud detection of muti-spectral satellite imagery.

Data availability

In this study, all the used data is available at least on May 8, 2024. In detail, the GF5 data is available at https://data.cresda.cn/; For readers within China, the link should work without any issues; For readers outside of China who may require access to the data, we suggest reaching out to the corresponding author or the hosting institution to explore alternative means of data access. The MODIS data is available at https://ladsweb.modaps.eosdis.nasa.gov/; The Himawari-8 data is available at ftp://ftp.ptree.jaxa.jp/jma/netcdf/; The CALIPSO data is available at https://search.earthdata.nasa.gov/. Experimental results provided by the corresponding author and are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

King, M. D., Platnick, S., Menzel, W. P., Ackerman, S. A. & Hubanks, P. A. Spatial and temporal distribution of clouds observed by MODIS onboard the Terra and Aqua satellites. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 51, 3826–3852 (2013).

Harshvardhan, Randall, D. A. & Corsetti, T. G. Earth radiation budget and cloudiness simulations with a general circulation model. J. Atmos. Sci. 46, 1922–1942 (1989).

Zhao, C. et al. A new cloud and aerosol layer detection method based on micropulse lidar measurements. J. Geophys. Research: Atmos. 119, 6788–6802 (2014).

Lv, H., Wang, Y. & Shen, Y. An empirical and radiative transfer model based algorithm to remove thin clouds in visible bands. Remote Sens. Environ. 179, 183–195 (2016).

Kazantzidis, A., Eleftheratos, K. & Zerefos, C. Effects of Cirrus cloudiness on solar irradiance in four spectral bands. Atmos. Res. 102, 452–459 (2011).

Seze, G. & Rossow, W. B. Time-cumulated visible and infrared radiance histograms used as descriptors of surface and cloud variations. Int. J. Remote Sens. 12, 877–920 (1991).

Rossow, W. B. & Garder, L. C. Cloud detection using satellite measurements of infrared and visible radiances for ISCCP. J. Clim. 6, 2341–2369 (1993).

Saunders, R. W. & Kriebel, K. T. An improved method for detecting clear sky and cloudy radiances from AVHRR data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 9, 123–150 (1988).

Kriebel, K. T., Gesell, G., Ka Stner, M. & Mannstein, H. The cloud analysis tool APOLLO: improvements and validations. Int. J. Remote Sens. 24, 2389–2408 (2003).

Stowe, L. et al. Global distribution of cloud cover derived from NOAA/AVHRR operational satellite data. Adv. Space Res. 11, 51–54 (1991).

Wylie, D. P. & Menzel, W. Two years of cloud cover statistics using VAS. J. Clim. 2, 380–392 (1989).

Wylie, D. P., Menzel, W. P., Woolf, H. M. & Strabala, K. I. four years of global cirrus cloud statistics using HIRS. J. Clim. 7, 1972–1986 (1994).

Zhu, Z. & Woodcock, C. E. Object-based cloud and cloud shadow detection in Landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 118, 83–94 (2012).

Zhu, Z., Wang, S. & Woodcock, C. E. Improvement and expansion of the Fmask algorithm: cloud, cloud shadow, and snow detection for Landsats 4–7, 8, and Sentinel 2 images. Remote Sens. Environ. 159, 269–277 (2015).

He, Q. Night-time cloud detection for FY-3A/VIRR using multispectral thresholds. Int. J. Remote Sens. 34, 2876–2887 (2013).

Frey, R. A. et al. Cloud detection with MODIS. Part I: improvements in the MODIS cloud mask for collection 5. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 25, 1057–1072 (2008).

Takahito, I. & Ryo, Y. Algorithm theoretical basis for Himawari-8 cloud mask product. Meteorological Satell. Cent. Tech. Note. 61, 17 (2016).

Shao, Z., Pan, Y., Diao, C. & Cai, J. Cloud detection in remote sensing images based on multiscale features-convolutional neural network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57, 4062–4076 (2019).

Li, L., Li, X., Jiang, L., Su, X. & Chen, F. A review on deep learning techniques for cloud detection methodologies and challenges. Signal. Image Video Process. 15, 1527–1535. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11760-021-01885-7 (2021).

Blonski, S. et al. Synthesis of multispectral bands from hyperspectral data: validation based on images acquired by aviris, hyperion, ali, and etm+. (2003).

Tan, Z. et al. Detecting multilayer clouds from the geostationary advanced Himawari imager using machine learning techniques. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–12 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Cloud detection for Landsat imagery by combining the random forest and superpixels extracted via energy-driven sampling segmentation approaches. Remote Sens. Environ. 248, 112005 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Machine learning-based retrieval of day and night cloud macrophysical parameters over East Asia using Himawari-8 data. Remote Sens. Environ. 273 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2022.112971 (2022).

Segal-Rozenhaimer, M., Li, A., Das, K. & Chirayath, V. Cloud detection algorithm for multi-modal satellite imagery using convolutional neural-networks (CNN). Remote Sens. Environ. 237, 111446 (2020).

Mateo-García, G., Laparra, V. & López-Puigdollers, D. Gómez-Chova, L. Transferring deep learning models for cloud detection between Landsat-8 and Proba-V. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 160, 1–17 (2020).

Ye, L., Cao, Z., Xiao, Y. & Yang, Z. Supervised fine-grained cloud detection and recognition in whole-sky images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 57, 7972–7985 (2019).

Heidinger, A. et al. Using the NASA EOS A-Train to probe the performance of the NOAA PATMOS-x Cloud Fraction CDR. Remote Sens. 8, 511 (2016).

Vermote, E. F., Tanré, D., Deuze, J. L., Herman, M. & Morcette, J. J. Second simulation of the satellite signal in the solar spectrum, 6S: an overview. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 35, 675–686 (1997).

Wan, Z. & Li, Z. L. A physics-based algorithm for retrieving land-surface emissivity and temperature from EOS/MODIS data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 35, 980–996 (1997).

Yang, Y. et al. in IGARSS 2018–2018 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. 2543–2546 (IEEE).

Yu, X., Guo, X. & Wu, Z. Land Surface Temperature Retrieval from Landsat 8 TIRS—Comparison between Radiative transfer equation-based method, Split Window Algorithm and single Channel Method. 6, 9829–9852 (2014).

Shang, H. et al. A hybrid cloud detection and cloud phase classification algorithm using classic threshold-based tests and extra randomized tree model. Remote Sens. Environ. 302, 113957 (2024).

Wendisch, M. & Yang, P. Theory of Atmospheric Radiative Transfer: A Comprehensive Introduction (Wiley, 2012).

Zhang, C. et al. Application and evaluation of deep neural networks for Airborne Hyperspectral Remote sensing Mineral Mapping: a case study of the Baiyanghe Uranium Deposit in Northwestern Xinjiang, China. Remote Sens. 14, 5122 (2022).

Lei, X., Fan, Y., Li, K. C., Castiglione, A. & Hu, Q. High-precision linearized interpretation for fully connected neural network. Appl. Soft Comput. 109, 107572 (2021).

Hsu, K. Y., Li, H. Y. & Psaltis, D. Holographic implementation of a fully connected neural network. Proc. IEEE. 78, 1637–1645 (1990).

Belgiu, M. & Drăguţ, L. Random forest in remote sensing: a review of applications and future directions. ISPRS J. Photogrammetry Remote Sens. 114, 24–31 (2016).

Jia, Y. et al. GNSS-R soil moisture retrieval based on a XGboost machine learning aided method: performance and validation. Remote Sens. 11, 1655 (2019).

Zamani Joharestani, M., Cao, C., Ni, X., Bashir, B. & Talebiesfandarani, S. PM2. 5 prediction based on random forest, XGBoost, and deep learning using multisource remote sensing data. Atmosphere. 10, 373 (2019).

Yu, M., Masrur, A. & Blaszczak-Boxe, C. Predicting hourly PM2. 5 concentrations in wildfire-prone areas using a SpatioTemporal Transformer model. Sci. Total Environ. 860, 160446 (2023).

Wang, N., Zhang, G., Pang, W., Ren, L. & Wang, Y. Novel monitoring method for material removal rate considering quantitative wear of abrasive belts based on LightGBM learning algorithm. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 114, 3241–3253 (2021).

Fan, Y. & Sun, L. Satellite Aerosol Optical Depth Retrieval Based on Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN) and a combine Algorithm of Simplified Aerosol Retrieval Algorithm and Simplified and Robust Surface Reflectance Estimation (SREMARA). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 16, 4947–4962. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2023.3281777 (2023).

Yamamoto, H., & Tsuchida, S. Assessment of cloud cover characteristics over calibration test sites using modis cloud mask products. Int. Arch. Photogramm Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. XLII–3/W7, 83–86, doi:https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-3-W7-83-2019 (2019).

Liu, J., Weng, F. & Li, Z. Ultrahigh-resolution (250 m) regional surface PM 2.5 concentrations derived first from MODIS measurements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 60, 1–12 (2021).

Letu, H. et al. High-resolution retrieval of cloud microphysical properties and surface solar radiation using Himawari-8/AHI next-generation geostationary satellite. Remote Sens. Environ. 239, 111583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2019.111583 (2020).

Yang, Y., Zhao, C. & Fan, H. Spatiotemporal distributions of cloud properties over China based on Himawari-8 advanced Himawari Imager data. Atmos. Res. 240, 104927 (2020).

Chen, J., He, T., Jiang, B. & Liang, S. Estimation of all-sky all-wave daily net radiation at high latitudes from MODIS data. Remote Sens. Environ. 245, 111842 (2020).

Ying, W., Wu, H. & Li, Z. L. Net surface shortwave radiation retrieval using random forest method with MODIS/AQUA data. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Observations Remote Sens. 12, 2252–2259. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTARS.2019.2905584 (2019).

Lundberg, S. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv preprint arXiv:07874 (2017).

Holz, R. E. et al. Global moderate resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS) cloud detection and height evaluation using CALIOP. J. Geophys. Research: Atmos. 113 https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD009837 (2008).

Ma, N. et al. A hybrid CNN-transformer network with differential feature enhancement for cloud detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 20, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2023.3288742 (2023).

Shang, H. et al. Development of a daytime cloud and haze detection algorithm for Himawari-8 satellite measurements over central and eastern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 122, 3528–3543 (2017).

Qiu, S., Zhu, Z. & He, B. Fmask 4.0: improved cloud and cloud shadow detection in Landsats 4–8 and Sentinel-2 imagery. Remote Sens. Environ. 231, 111205 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China [42271412]. The author also expresses gratitude to NASA for providing MODIS data, to JMA for providing Himawari-8 data, and to the China Centre for Resources Satellite Data and Application for providing GF-5(02) imagery.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.S. and Y.F. contributed significantly to the analysis, performed the experiment and wrote the manuscript. L.S. contributed to the conception of the study and applied for funds. X.L., C.L. and S.P. were reviewed and edited. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, X., Fan, Y., Sun, L. et al. Cloud detection sample generation algorithm for nighttime satellite imagery based on daytime data and machine learning application. Sci Rep 14, 27917 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78889-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78889-z