Abstract

Planting forests is an effective way to improve desertification. In order to elucidate the impacts of different vegetation types on soil development and restoration of degraded lands, we compared the properties of soils at different depths in three plantation forests in the Hunsandak Sandy Land in the Chinese agro-pastoral ecotone (Ulmus pumila, Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica, and Populus simonii). The results show that all three plantation forests were able to significantly improve the soil properties, and they resulted in soil nutrient enrichment in the surface layer. As the soil depth increased, the soil became progressively poorer in nutrients, the fine particle content decreased, and the bulk density and water content increased. The orders of the fractal dimension characterization and soil improvement effects of the different tree species were as follows: U. pumila > P. sylvestris var. mongolica > P. simonii. Compared with the bare sand, the soil bulk density under the U. pumila plantation was 19% lower; the soil water content was 74% higher; the soil organic matter, total N, P, and K were 336%, 207%, 106%, and 31% higher; the available N, P, and K were 41%, 125%, and 21% higher; and the clay and silt contents were 498% and 387% higher, respectively. The ranges of the soil fractal dimension were 1.67–2.08 for the bare sandy land and 2.14–2.32 for the planted forests. The soil fractal dimension was strongly correlated with the soil physicochemical properties, especially with the soil nutrients and fine particle content, which exhibited highly significant correlations (p < 0.01), and the correlation coefficients were all greater than 0.8. Therefore, we believe that U. pumila is a suitable sand-fixing plant species in this area. In addition, the soil fractal dimension can be used as an important reference index for characterizing soil properties in sandy areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Desertification is a type of land degradation caused by climate and unsustainable land use. Desertification causes a series of environmental, economic, and social problems worldwide, especially in arid areas, and seriously threatens the sustainable development of human society1,2,3. The damage caused by the combination of wind and wind-blown sand not only affects the productivity and life of local people, but also affects the surrounding countries and regions worldwide4. Reducing land degradation and improving soil texture are important objectives when combating desertification5. More and more countries in the world choose to develop plantation forests in arid and semi-arid areas to improve the environment, and people have gradually come to realize the important role of planted vegetation and habitat restoration in regional ecological restoration6,7,8,9. Practice has proven that the restoration of vegetation on sandy land can significantly amend the properties of sandy soil10, increase soil nutrient contents11, promote soil organic carbon accumulation12, and accelerate soil development and recovery13. At present, appropriate revegetation measures have been universally recognized as one of the ways to effectively improve degraded land in desertified areas14,15,16.

China has the largest area of desertification worldwide and experiences the most serious damage from this desertification17. Annual losses of about US $6.8 billion are caused by land desertification in China18. Starting in 1978, China began implementing large-scale afforestation and ecological restoration projects in areas experiencing desertification19. Our study area is located in the Hunshandak Sandy Land, one of the four major sandy areas in China. This study was conducted in the ecological transitional zone between the eastern agricultural and western pastoral areas of China. The diversity of human activities and the special geographic location of the study area have led to frequent disturbances and extensive degradation of the ecosystem there, and land degradation has become an environmental, social, and economic problem in this region20,21. To effectively fix the quicksand and reduce wind-sand disasters, this region has become a key area for the construction of the Three-North Protective Forest, and the goverrnment has planted large areas of different types of plantation forests22. However, after a long period of natural succession, the ecological benefits of the different types of planted forests have been found to exhibit obvious differences23,24. For any degraded land affected by desertification around the world, the development and restoration of soil is a high-priority issue that cannot be ignored. Soil is the basic environment for the growth and living of soil organisms and other species that depend on them. Changes in soil physical and chemical properties are signs of soil formation, development, and evolution, which directly affect the growth, reproduction, and metabolic functions of soil organisms25,26. Since soil is a porous medium composed of soil particles with different shapes and sizes, its structural properties are very complex. Therefore, since the 1980s, the fractal theory has been widely used as a tool to reveal the local structure and morphology of substances in the study of soil structure27,28. The soil fractal dimension is an important index for describing the complexity of the soil structure, which reflects the distribution and morphological characteristics of the internal spaces in soil29. The larger the soil fractal dimension is, the more complex the soil structure is, and the more uniform the pore distribution is30,31. In a large number of previous studies, the fractal dimension of soil particles has been used as a quantitative index to evaluate the soil structure and fertility characteristics32,33,34,35, and some studies have confirmed that the fractal dimension can be used as a representative indicator of the degree of desertification36.

Although several studies have reported the effects of planting different vegetation in sandy areas with different soil properties37,38,39, relevant studies of sandy lands in agro-pastoral ecotones with frequent human behavioral disturbances still need to be supplemented. After the afforestation of desertified land, people tend to pay more attention to changes in soil indicators, and studies on the soil fractal dimension under different vegetation types are not common. In addition, long-term manual management of planted forests has been conducted in many desertified areas, and the research sample sites in our study contain planted forests under natural restoration and rain-fed conditions. The results of our study provide a scientific reference for the restoration of vegetation in agricultural and pastoral transition zones, ecologically fragile areas, and desertification areas. The purpose of this study was to test the following hypotheses: (1) the effects of different vegetation types on soil properties are significantly different under natural restoration conditions and there is a certain regularity in the vertical distribution of the soil properties; and (2) the soil fractal dimension is affected by the vegetation type, and there is a strong correlation between the size of the soil fractals and the soil physicochemical properties. The fractal dimension plays a certain role in characterizing regional soil properties.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

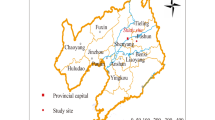

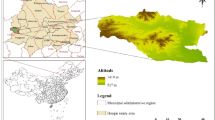

The study area is located 180 km north of Beijing in Duolun County, Xilin Gol League (City), Eastern Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Province), China. The physical geographical unit is located at the intersection of the residual vein of the Greater Hinggan Mountains, the northern foot of Yinshan Mountain, and the residual vein of Yanshan Mountain, at the southeastern edge of the Hunshandake Sandy Land. The study area is a typical area used for a combination of agriculture and animal husbandry in the ecotone of northern China. The landforms mainly include low mountains, hills, valley depressions, sloping plains in front of mountains, high platforms, and stacked dunes. The typical continental climate experiences a temperate semi-arid to semi-humid transition. The average elevation is 1350 m, while the average annual precipitation, windspeed, and temperature are 385 mm, 3.6 m/s, and 1.6 °C, respectively. The long and cold winters are part of a climate with no obvious summer, strong winds, and sufficient light, water, and heat in the warm season23. According to the relevant data of the local government, in the 1970s and 1980s, the joint impact of natural and human factors caused the environment of Duolun County to continuously deteriorate, to the point where the area of desertification exceeded 70% of the total area of the county. By October 2023, 274,533 hm2 of desertified land in Duolun County had been effectively managed for sand stabilization, and only 1,267 hm2 of mobile and semi-fixed sandy areas remained to be restored. The government mainly manages desertified land by banning grazing, returning farmland to forest, and planting a large amount of sand-fixing forest22.

Sample plot setting

In August 2023, a field survey of the study area revealed that the main tree species in the surviving relatively complete plantation in this area were Ulmus pumila, Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica, and Populus simonii. The researchers selected U. pumila, P. sylvestris var. mongolica, and P. simonii forests with the same site conditions, similar age in years since planting, and similar planting density as the study samples, while a nearby bare sandy land without afforestation was selected as the control plot. There were three replicate plots of each type of plot, a total of 12 plots. Basic information on sample plots are shown in Table 1. The selected forest lands had not been artificially tended or managed since planting.

Soil sample collection and analysis

Soil samples were collected in August 2023. For each plot, one large 30 m × 30 m plot was set up, a total of 12 large sample plots, and three small 10 m × 10 m plots were set up along the diagonal direction of each large plot, a total of 36 small sample plots. Three soil sampling points were evenly selected on the diagonal of each small sample plot. A soil profile with a depth of 60 cm was excavated at each sampling point, and then undisturbed soil was collected in three layers from soil depths of 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm. Soil samples were collected from the same soil layer in three sampling points in each small sample plot and were mixed together prior to analysis of the soil properties. Finally, nine soil samples from each large sample plot were analyzed, 27 soil samples were from each sample plot type were analyzed, and a total of 108 soil samples were analyzed.

The soil samples used to determine water content (SWC) and bulk density (SBD) were sampled with a ring knife of 100 m3 and determined by dry weight. Samples used to determine other soil properties are brought back to the laboratory in sealed bags, plant residues were removed, and soil was air-dried in dark conditions. The volume fraction of the soil particle size of each different plantation sample was determined by an Analysette 22 MicroTecPlus laser particle size analyzer manufactured by Fritsch GmbH in Idar-Oberstein, Germany. The soil organic matter (SOM) was measured using the volumetric heating method with potassium dichromate. The available nitrogen (AN) was measured using the alkali-diffusion method. The available phosphorus (AP) was measured using the 0.5 mol/L NaHCO3-H2SO4 leaching z-molybdenum antimony anti-colorimetric assay method. The available potassium (AK) was measured using the 1 mol/L CH3COONH4 leaching-flame photometric method. The total nitrogen (TN) was measured using the concentrated sulfuric acid with perchloric acid mixed cooking by the Kjeldahl method. The total phosphorus (TP) was measured using the concentrated sulfuric acid-perchloric acid mixed cooking-molybdenum antimony anti-colorimetric method. The total potassium (TK) was measured using the acid dissolution-flame photometric method. This experiment consisted of three forest lands with different tree species and a bare sand plot.

Soil fractal dimension

The soil was divided into: clay (r < 0.02 mm), silt (0.02 mm < r < 0.05 mm), very fine sand (0.05 mm < r < 0.1 mm), fine sand (0.1 mm < r < 0.25 mm), medium sand (0.25 mm < r < 0.5 mm), coarse sand (0.5 mm < r < 1 mm), and very coarse sand (1 mm < r < 2 mm). This was based on the United States Department of Agriculture soil texture grading standards. Based on the particle size volume data obtained from the laser particle size analyzer, the following volume fractal dimension formula was obtained based on the concept of volume fractal dimension of soil particles using calculation formula deduced by Tyler et al.40:

Taking logarithms on both sides of Eq. (1) at the same time gives the formula for the dimensionality of the soil fractal:

where V is the total volume of soil smaller than the particle size R (%); VT is the total volume of soil measured (%); R is the average value of the particle size between the two sieve particle size classes Ri and Ri +1 (mm); Rmax is the largest particle size in the soil particle size grading, and the largest particle size of the soil in this study is 2 mm; D is the volumetric fractal dimension of the soil particles, where the left and right sides of the Eq. (2) has the longitudinal and transverse coordinates, respectively, of the linear regression fitting equation, to find the slope value, the difference between 3 and the slope value of the straight line is the value of the soil fractal dimension D.

Data processing and analysis

The normality of the data variables was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnova test at a significance level of α = 0.05. For the variables that did not conform to a normal distribution, we transformed the natural logarithm, square root, and derivative of the data to make the data variables obey a normal distribution (P > 0.05). The variance homogeneity test was also performed on the data variables, which yielded P > 0.05, indicating that the fluctuations of the data in the different groups were consistent and met the requirements of variance homogeneity. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant difference multiple comparisons were used to determine if the differences in the soil physicochemical properties across the sites were statistically significant (at the 0.05 probability level for the Duncan and Games-Howell multiple comparisons). The relationship between the fractal dimension of soil particles and the percentage of particles in each soil grain size was analyzed using linear regression analysis, while the effect of soil properties on the fractal dimension of soil was analyzed using path analysis. The correlations between the soil physical and chemical properties were analyzed via Pearson correlation analysis (two-tailed). Statistical significance was defined as significant at P < 0.05 and highly significant at P < 0.01. All of the above data analysis processes were conducted using SPSS 26.0 software. All of the data presented in this paper are the mean ± standard deviation of three replicate determinations for all of the types of sample plots, and on the graphs, the standard deviation is presented in the form of error bars. The plots were created using Origin Pro 2021.

Results

Soil particle size characterization

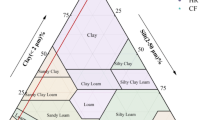

Afforestation in sandy land significantly reduced soil particle size (Table 2). Compared with the bare sandy land, the volume percentages of the clay, silt, and very fine sand in the plantations were 0.24–0.88%, 3.16-11.91%, and 1.61–6.59% higher, respectively. Moreover, the percentages of fine, medium, coarse, and very coarse sand decreased by 0.96–5.26%, 0.98–9.38%, 0.89–2.5%, and 1.41–1.79%, respectively. At the same soil depth, the volume percentage content of soil clay, silt, and very fine sand was: U. pumila > P. sylvestris var. mongolica > P. simonii > bare sandy land, while the volume percentage content of soil fine sand and medium sand was: U. pumila < P. sylvestris var. mongolica < P. simonii < bare sandy land. The volume contents of the clay, silt, and very fine sand decreased with increasing soil depth, ad the contents of the clay, silt, medium sand, and coarse sand in the different plantation plots were significantly different in each soil depth layer (p < 0.05). The soil texture of U. pumila forest was mainly sandy and loamy sandy soils, while that of P. sylvestris var. mongolica, P. simonii and bare sandy land were sandy soil (Fig. 1).

Soil particle fractal dimensions

The average fractal dimension (D) of the soil particles in the three plantations and that of the bare sandy land are shown in Table 3. The D values of all of the soil depth layers exhibited the following change pattern: U. pumila > P. sylvestris var. mongolica > P. simonii > bare sandy land. The fractal dimension of the same sample plot decreased with increasing soil depth, and the fractal dimension of all soil depths had significant differences (p < 0.05).

Characterization of soil water content and bulk density

Soil water content and bulk density in different plots had significant differences in each soil depth (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Compared with the bare sandy land, the soil water contents in the plantation sample plots were 1.57–4% higher. Soil bulk density was reduced by 0.1–0.35 g·cm− 3. The variations in the soil water content and bulk density were 0–20 cm < 20–40 cm < 40–60 cm. The soil water contents at the same soil depth were as follows: U. pumila > P. sylvestris var. mongolica > P. simonii > bare sandy land. In addition, the order of the soil bulk density was as follows: U. pumila < P. sylvestris var. mongolica < P. simonii < bare sandy land.

Soil nutrient characterization

Afforestation on sandy land significantly increased soil nutrient content (Fig. 3). At the same soil depth, the contents of the soil organic matter, total nutrients, available nitrogen, and available phosphorus exhibited the following change regularity: U. pumila > P. sylvestris var. mongolica > P. simonii > bare sandy land, and the difference was significant among all plots (p < 0.05). The soil nutrients in all of the types of land decreased with increasing depth. The soil available potassium contents of the three plantations were higher than that of the bare sandy land, but there was no significant difference in the soil available potassium among the three types of forest land (p > 0.05). In the same plantation sample, the soil nutrients, except for the available potassium, were significantly different at different soil depths (p < 0.05), but the available potassium was not significantly different at soil depths of 20–40 cm and 40–60 cm in the plantations (p > 0.05).

Relationship between soil properties

Regression analysis was performed on the soil particle percentage content and fractal dimension (D) (Fig. 4). The D values were highly significantly positively correlated with the contents of the clay, silt, and very fine sand (p < 0.01). It was highly significant negative correlated with the percentage of fine and medium sand (p < 0.01). There was a significant negative correlation with the percentage of coarse and very coarse sand (p < 0.05). The D values were mainly affected by the soil particles smaller than 0.5 mm. The particle size of 0.1 mm was the boundary of the change in the D value. The greater the content of the fine particulate matter less than 0.1 mm in the soil was, the higher the D value was.

The relationship between the soil fraction grain percentage and fractal dimension: (a) clay (r < 0.02 mm); (b) silt (0.02 mm < r < 0.05 mm); (c) very fine sand (0.05 mm < r < 0.1 mm); (d) fine sand (0.1 mm < r < 0.25 mm); (e) medium sand (0.25 mm < r < 0.5 mm); (f) coarse sand (0.5 mm < r < 1 mm); and (g) very coarse sand (1 mm < r < 2 mm).

The soil fractal dimension was highly significantly positive correlated with soil clay, silt, organic matter, total available nutrients, and available nutrients, and highly significantly negative correlated with soil sand and bulk density (Fig. 5). The index that had the smallest correlation with soil fractal dimension and grain size distribution was water content, in which the soil fractal dimension and clay were significantly positive correlated with water content, while silt and sand were not significantly correlated with water content. Moreover, soil water content was not significantly correlated with bulk density, total phosphorus, and available potassium, but was significantly positive correlated with organic matter, total nitrogen, total potassium, available nitrogen, and available phosphorus. In addition, the bulk density and sand content were highly significantly negative correlated with organic matter, total available nutrients, and available nutrients, and the organic matter, total available nutrients, and available nutrients were highly significantly positive correlated with each other.

The influence of soil characteristics on fractal dimension (D) was further explained by the path analysis method. The independent variables of path analysis were the soil physical and chemical properties; and the dependent variable was soil fractal dimension. The normal distribution test of the dependent variables showed that p was greater than 0.05 (Table 4); the dependent variables followed a normal distribution. The analysis results showed that soil fractal dimension was mainly affected by soil bulk density and soil clay content (Table 5). The bulk density had a significant negative effect on the D value, while the clay content had a significant positive effect on the fractal dimension (Table 5).

Discussion

The results of this study reveal that the construction of the types of sand fixation forests in mobile sandy areas had a positive effect on the soil properties, but there was a significant difference in the effects of the different vegetation types on the soil. The soil nutrient accumulation was mainly concentrated in the top soil layer (0–20 cm), and. With increasing soil depth, the soil nutrient content and fine particle content gradually decreased, and the soil capacity and water content gradually increased (Fig. 6). Many recent related studies on sand fixation vegetation in sandy areas have yielded similar conclusions. Haonian Li et al.38. found that the construction of mixed vegetation types in the desert-Yellow River transition zone had a good positive effect on the soil physical properties and nutrient contents, but the effects of different mixing patterns on the soil were different. Other scholars39 have studied the effects of different types of plantation forests on alpine sandy soils on the Tibetan Plateau and have found that soil improvement by different plantation forests occurred mainly in the shallow layer. This is mainly due to the fact that the sand-fixing forests not only prevented the movement of wind-blown sand but also protected the soil and created a special microclimate that allowed for soil development. In the sheltered area of the sand-fixation forests, part of the air-borne dust naturally settles on the surface due to gravity, while the other parts adhere to leaves and branches. This imported soil then resupplies to the nutrients and fine soil particles to the soil surface along with “stem flow” along tree trunks or “canopy rain”, adding to the aeolian sand soil41,42.

The results of this study revealed that the soil fractal dimension was strongly correlated with the soil physicochemical properties (Fig. 6), especially the soil nutrients and fine particle content. which both exhibited highly significant correlations (p < 0.01), and the correlation coefficients were all greater than 0.8. The correlations between the soil fine particle content and soil nutrients were also highly significant (p < 0.01). Therefore, the higher the soil fine particle content was, the higher the soil fractal dimension was, and the better the soil nutrient status in the plantation forest was. Changes in the soil properties often represent the degree of land degradation in desertified areas, and the soil fractal dimension can quantitatively describe this phenomenon. In summary, we believe that the soil fractal dimension can be used as an important reference index to characterize soil properties in sandy areas. In forested ecosystems, strong correlations usually exist among the various soil physicochemical properties13,43. Related studies have also analyzed soil properties under different vegetation types or different densities of the same vegetation in sandy areas in arid and semi-arid regions, and they have concluded that a reduction in soil coarse particles increases the soil nutrient contents and the fractal dimension38,44. The soil structure plays an important role in regulating the soil quality and its ecological function, which directly affect the soil water movement (infiltration and evaporation), soil air quantity and quality, and soil nutrient conversion and supply45,46. Soil particles are the basis of the soil structure, and the soil particle size and the combination and ratio of various particles directly affect the basic properties of soil. Strong adsorption and particle combinations exist between soil particles and organic matter. The loose porous structure of soil organic matter not only plays a key role in the formation of soil aggregates but also improves the exchange and absorption capacities of water and nutrients47,48. Scholars in industry have conducted relevant research on the influences of land use types on the soil particle size distribution and fractal dimension. They have concluded that the fractal dimension of soil particles can better reflect the characteristics of the soil structure and fertility32. Jifeng Deng et al.36 studied sand-fixing forests with different stand densities in the Mu Us Desert and confirmed that the fractal dimension is a sensitive and useful indicator for evaluating the degree of desertification. This is consistent with the results of our study.

This research shows that U. pumila is the most suitable sand fixing species in the Hunshandake Sandy Land when compared with the sand fixing of P. sylvestris var. mongolica and P. simonii. It has long been reported that Populus and Pinus plantations are not sustainable for vegetation restoration in sandy lands because these species require more water than is naturally available in many landscapes49. In fact, in some sandy areas of China, U. pumila plant communities have formed a unique natural landscape of sparse U. pumila forest through long-term natural succession. In some cases, even a large number of ancient U. pumila trees that have survived for more than 100 years. These precious ancient U. pumila resources are the result of long-term natural selection. Previous studies have shown that U. pumila is the climax community of psammophytic succession because it is adapted to arid and semi-arid climates in typical steppe landscapes, and is also the main retrogressive succession community in forest steppe during desertification50,51. The economy of the present research area is driven by a combination of agriculture and animal husbandry in an area with a typical continental climate in a temperate semi-arid to semi-humid transition. Ulmus pumila trees can well adapt to the natural environment of the research area. In recent years, sand-fixing forests have become increasingly important to the local government, and these forests have been well protected from human interference. A positive interaction exists between good forest growth and soil quality.

During the restoration of vegetation in sandy land habitats, the development and restoration of soil is a long and complicated process. The forest density, plantation age, and different management measures in a forested landscape will change the growth of individual trees and the forest community structure. The change of surface vegetation will affect the soil microenvironment, which in turn affects the ability of the soil to retain water and fertilizer. The present research is based on the conclusion that different types of sand-fixing forests have similar densities and ages but do not require active forest management. Additional studies and analysis of the changes of sand-fixing forests after long-term natural succession or active forest management are still needed and the direction of future research.

Conclusions

Ulmus pumila, P. sylvestris var. mongolica and P. simonii all had positive effects on the soil properties of sandy land in eastern Inner Mongolia, China. Afforestation on sandy land significantly reduced soil particle size and soil bulk density, increased soil fine particle, water, and nutrient content. The overall soil improvement effect was U. pumila > Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica > P. simonii. Compared with the bare sandy land, the soil bulk density under the U. pumila plantation was 19% lower, and the soil water content, soil organic matter, total nitrogen, total phosphorus, total potassium, available nitrogen, available phosphorus, available potassium, clay, and silt content were 74%, 336%, 207%, 106%, 31%, 41%, 125%, 21%, 498%, and 387% higher, respectively. The plantation effectively improved the surface soil in all of the forest treatments. The volume contents of the clay and silt and the soil nutrient contents of the same sample plot decreased with increasing depth. The soil water content and bulk density increased with increasing depth. These findings prove that our first hypothesis is valid. The soil fractal dimension was obviously different in each type of forest and exhibited the following order in all of the soil layers: U. pumila > Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica > P. simonii > bare sandy land. The clay and silt contents and bulk density of the soil were closely related to the accumulation of soil nutrients. The soil fractal dimension was strongly correlated with the soil physicochemical properties, especially with soil nutrients and fine particle content, which exhibited highly significant correlations (p < 0.01), and the correlation coefficients were all greater than 0.8. The particle size of 0.1 mm was the boundary particle size of the change in the fractal dimension. The greater the content of fine particulate matter less than 0.1 mm in the soil, the higher the fractal dimension of the soil. These findings suggest that our second hypothesis is also valid. Therefore, we believe that U. pumila is a suitable sand-fixing plant species in this area. In addition, the soil fractal dimension can be used as an important reference index to characterize soil properties in sandy areas. The results of this study provide a scientific reference for the restoration of vegetation in desertification areas.

Data availability

Relevant data from this study can be obtained upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author of this article by email (yg@imau.edu.cn).

References

D’Odorico, P., Bhattachan, A., Davis, K. F., Ravi, S. & Runyan, C. W. Global desertification: drivers and feedbacks. Adv. Water Resour. 51, 326–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2012.01.013 (2013).

Little, P. D. The social context of land degradation (“desertification”) in dry regions. In Population and Environment, 209–251. (Routledge Publications, 2019).

Sterk, G. & Stoorvogel, J. J. Desertification–scientific Versus Political realities. Land. 9, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050156 (2020).

Normile, D. Getting at the roots of killer dust storms. Science. 317, 314–316. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.317.5836.314 (2007).

Abdelhak, M. Soil improvement in arid and semiarid regions for sustainable development. In Natural Resources Conservation and Advances for Sustainability, 73–90. (Elsevier Publications, 2022).

Çalişkan, S. & Boydak, M. Afforestation of arid and semiarid ecosystems in Turkey. Turk. J. Agric. For. 41, 317–330. https://doi.org/10.3906/tar-1702-39 (2017).

Kaul, R. & Ganguli, B. Afforestation studies in the arid zone of India. In Proceedings of symposium on problems of Indian arid zone, 183–187. (Ministry of Education, Goverment of India, New Delhi, 1964).

Wang, L. & Li, X. Soil Microbial Community and their relationship with Soil properties across various landscapes in the Mu us Desert. Forests. 14, 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14112152 (2023).

Yıldız, O. et al. Restoration success in afforestation sites established at different times in arid lands of Central Anatolia. For. Ecol. Manag. 503, 119808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119808 (2022).

Lyu, D., Liu, Q., Xie, T. & Yang, Y. Impacts of different types of Vegetation Restoration on the Physicochemical properties of Sandy Soil. Forests. 14, 1740. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14091740 (2023).

Boulmane, M., Oubrahim, H., Halim, M., Bakker, M. R. & Augusto, L. The potential of Eucalyptus plantations to restore degraded soils in semi-arid Morocco (NW Africa). Ann. For. Sci. 74, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-017-0652-z (2017).

Yosef, G. et al. Large-scale semi-arid afforestation can enhance precipitation and carbon sequestration potential. Sci. Rep. 8, 996. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19265-6 (2018).

Guo, X. et al. Changes in Vegetation and Soil Properties between shelterbelts of Populus Simonii in Naiman Sand Zone of Horqin Sandy Land Area. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 42, 129–136. https://doi.org/10.13961/j.cnki.stbctb.2022.06.017 (2022).

Al-Obaidi, J. R. et al. The environmental, economic, and social development impact of desertification in Iraq: a review on desertification control measures and mitigation strategies. Environ. Monit. Assess. 194, 440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-022-10102-y (2022).

Gao, S., Wu, J., Ma, L., Gong, X. & Zhang, Q. Introduction to sand-restoration technology and model in China. Sustainability. 15, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010098 (2022).

Medugu, N. I., Majid, M. R., Johar, F. & Choji, I. The role of afforestation programme in combating desertification in Nigeria. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2, 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/17568691011020247 (2010).

Zhang, Z. & Huisingh, D. Combating desertification in China: monitoring, control, management and revegetation. J. Clean. Prod. 182, 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.233 (2018).

Cao, S. Why large-scale afforestation efforts in China have failed to solve the desertification problem. In Environmental Science&Technology, 1826-1831. (ACS Publications, 2008).

Cao, S. Impact of China’s large-scale ecological restoration program on the environment and society in arid and semiarid areas of China: achievements, problems, synthesis, and applications. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 317–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/10643380902800034 (2011).

Dang, D., Li, X., Li, S. & Dou, H. Ecosystem services and their relationships in the grain-for-green programme—A case study of Duolun County in Inner Mongolia, China. Sustainability. 10, 4036. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10114036 (2018).

Li, Z., Xie, Y., Ning, X., Zhang, X. & Hai, Q. Spatial distributions of salt-based ions, a case study from the Hunshandake Sandy Land, China. Plos One. 17, e0271562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271562 (2022).

Sand control twenty years to create Duolun model green into the sand retreat to protect the northern border carving and casting the Great Green Wall. News article of the Xilin Gol League Administrative Office of the People’s Republic of China. https://www.xlgl.gov.cn/xlgl/zt/zdgz/wrfz/2023100910452293656/index.html (2023).

Dai, L., Tang, H., Zhang, Q. & Cui, F. The trade-off and synergistic relationship among ecosystem services: a case study in Duolun County, the agro-pastoral ecotone of Northern China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 40, 2863–2876. https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201904050663 (2020).

Li, H. & Yang, X. Advances and problems in the understanding of desertification in the Hunshandake Sandy Land during the last 30 years. Adv. Earth Sci. 25, 647. https://doi.org/10.11867/j.issn.1001-8166.2010.06.0647 (2010).

Lee, K. & Pankhurst, C. Soil organisms and sustainable productivity. Soil. Res. 30, 855–892. https://doi.org/10.1071/SR9920855 (1992).

Normand, A. E., Smith, A. N., Clark, M. W., Long, J. R. & Reddy, K. R. Chemical composition of soil organic matter in a subarctic peatland: influence of shifting vegetation communities. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 81, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2016.05.0148 (2017).

Armstrong, A. On the fractal dimensions of some transient soil properties. J. Soil Sci. 37, 641–652 (1986).

Perfect, E., Rasiah, V. & Kay, B. Fractal dimensions of soil aggregate-size distributions calculated by number and mass. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 56, 1407–1409 (1992).

Lafond, J., Han, L., Allaire, S. & Dutilleul, P. Multifractal properties of porosity as calculated from computed tomography (CT) images of a sandy soil, in relation to soil gas diffusion and linked soil physical properties. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 63, 861–873 (2012).

Ju, X., Jia, Y., Li, T., Gao, L. & Gan, M. Morphology and multifractal characteristics of soil pores and their functional implication. Catena. 196, 104822 (2021).

Tarquis, A. M., Torre, I. G., Martín-Sotoca, J. J., Losada, J. C., Grau, J. B., Bird, N. R., & Saa-Requejo, A. Scaling characteristics of soil structure. In Pedometrics, 155–193. (Springer Publications, 2018).

Wang, D., Fu, B., Zhao, W., Hu, H. & Wang, Y. Multifractal characteristics of soil particle size distribution under different land-use types on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena. 72, 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2007.03.019 (2008).

Ahmadi, A., Neyshabouri, M. R., Rouhipour, H. & Asadi, H. Fractal dimension of soil aggregates as an index of soil erodibility. J. Hydrol. 400, 305–311 (2011).

Ghanbarian, B. & Daigle, H. Fractal dimension of soil fragment mass-size distribution: a critical analysis. Geoderma. 245, 98–103 (2015).

Wang, Y., He, Y., Zhan, J. & Li, Z. Identification of soil particle size distribution in different sedimentary environments at river basin scale by fractal dimension. Sci. Rep. 12, 10960 (2022).

Deng, J., Li, J., Deng, G., Zhu, H. & Zhang, R. Fractal scaling of particle-size distribution and associations with soil properties of Mongolian pine plantations in the Mu us Desert, China. Sci. Rep. 7, 6742 (2017).

Fan, L. et al. Patterns of soil microorganisms and enzymatic activities of various forest types in coastal sandy land. Global Ecol. Conserv. 28, e01625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01625 (2021).

Li, H., Meng, Z., Dang, X. & Yang, P. Soil properties under artificial mixed forests in the desert-yellow river coastal transition zone, China. Forests. 13, 1174. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13081174 (2022).

Li, Q., Jia, Z., Liu, T., Feng, L. & He, L. Effects of different plantation types on soil properties after vegetation restoration in an alpine sandy land on the Tibetan Plateau, China. J. Arid Land. 9, 200–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-017-0006-6 (2017).

Tyler, S. W. & Wheatcraft, S. W. Application of fractal mathematics to soil water retention estimation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 53, 987–996. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1989.03615995005300040001x (1989).

Cheng, Y. et al. New measures of deep soil water recharge during the vegetation restoration process in semi-arid regions of northern China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 24, 5875–5890. https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-24-5875-2020 (2020).

Ding, J. et al. Effects of an oasis protective system on aeolian sediment deposition: a case study from Gelintan oasis, southeastern edge of the Tengger Desert, China. J. Mt. Sci. 17, 2023–2034 (2020).

Eslaminejad, P. et al. Plant species and season influence soil physicochemical properties and microbial function in a semi-arid woodland ecosystem. Plant. Soil. 456, 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-020-04691-1 (2020).

Feng, X., Qu, J., Tan, L., Fan, Q. & Niu, Q. Fractal features of sandy soil particle-size distributions during the rangeland desertification process on the eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Soils Sediments. 20, 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02392-6 (2020).

Oades, J. M. The role of biology in the formation, stabilization and degradation of soil structure. In Soil structure/soil Biota Interrelationships, 377–400. (Elsevier Publications, 1993).

Vogel, H. J. et al. A holistic perspective on soil architecture is needed as a key to soil functions. Eur. J. Soil. Sci. 73, e13152. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.13152 (2022).

Bucka, F. B., Kölbl, A., Uteau, D. & Peth, S. Kögel-Knabner, I. Organic matter input determines structure development and aggregate formation in artificial soils. Geoderma. 354, 113881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.113881 (2019).

Edwards, A. P. & Bremner, J. Microaggregates in soils 1. J. Soil Sci. 18, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.1967.tb01488.x (1967).

Li, G. Studies on Steppe-Woodland Vegetation Restoration Mechanism in Keerqin Sandy Land. PhD dissertation, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot (2004).

Li, G., Wang, Y., Yu, X., Li, Q. & Yue, Y. Spatial patterns of elm density in Otingdag sandy land. J. Arid Land. Resour. Environ. 25, 141–145. https://doi.org/10.13448/j.cnki.jalre.2011.03.001 (2011).

Tang, J., Jiang, D. & Wang Y.-c. A review on the process of seed-seedling regeneration of Ulmus pumila in sparse forest grassland. Chin. J. Ecol. 33, 1114. https://doi.org/10.13292/j.1000-4890.2014.0118 (2014).

Acknowledgements

We thank LetPub (www.letpub.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript. This research was funded by the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Programme grant number 2021GG0070, the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Water Resources Department Financial Special grant number WH-1833-ZHJC-FW, and the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Natural Science Foundation grant number 2021MS03055.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This article was conceptualised by X.G. and G.Y.; X.G. wrote the main manuscript text; X.G. and S.Q prepared all figures; X.G. and S.Q and Y.M. completed sample collection and experiments. G.Y. and Y.M. were responsible for proofreading and checking manuscripts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, X., Yang, G., Ma, Y. et al. Effects of different sand fixation plantations on soil properties in the Hunshandake Sandy Land, Eastern Inner Mongolia, China. Sci Rep 14, 27904 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78949-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78949-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Soil quality changes in the Horqin sandy area under different ecological restoration patterns

Scientific Reports (2025)