Abstract

There are few analyses comparing complete nephrectomy with resection of the renal parenchyma only (CN) or radical nephrectomy that includes simultaneous resection of the parenchyma, affected perirenal fascia, perirenal fat, and ureter (RN) relative to partial nephrectomy (PN) for patients with nonmetastatic (M0) renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in terms of overall survival (OS). This study aimed to evaluate the effect of different nephrectomy on the OS of M0 RCC and to identify the main beneficiaries of different nephrectomy. The data was collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. Kaplan–Meier plots, and multivariable Cox regression models were used. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed to reduce the effect of selection bias. A prognostic model for M0 RCC patients after nephrectomy was established using the deep learning framework. Stage I M0 RCC patients who received PN did not have a better prognosis than none surgery in terms of CSS and OS after PSM. Stage I M0 RCC patients who received PN did not have a better prognosis than CN in terms of CSS but had in terms of OS after PSM. Stage I M0 RCC patients who received PN had a better prognosis in terms of CSS and OS after PSM. The test set AUC values for 1/3/5/7/9 year survival prediction of the surgical decision model were 0.844, 0.812, 0.794, 0.79, 0.813. For OS and CSS in M0 RCC patients, PN was superior to CN and RN regardless of grade. But for grade I, PN and none surgery did not show significant differences. In order to further categorize surgical patients and make more precise decisions regarding their treatment, a surgical decision-making model has been established.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a complex malignancy with a multifactorial etiology, including genetic susceptibility, exposure to environmental carcinogens, and certain medical conditions1. RCC constitutes roughly 2.3% of all newly diagnosed malignant tumors in males and 1.3% in females2, with a higher incidence rate observed in Western countries3. The incidence of RCC has been increasing at a rate of approximately 1% annually in recent times2, and staging migration has contributed to a rise in the detection of early-stage RCC4. Consequently, surgical treatments for patients with low-stage RCC are attracting increasing interest5.

For localized RCC, surgical intervention remains the primary and most effective radical treatment modality6. The utilization of radiotherapy and chemotherapy is restricted in the management of M0 RCC7,8. It is well-established that for patients with localized T1 RCC, partial nephrectomy (PN) is preferentially employed over radical nephrectomy (RN) or complete nephrectomy (CN)6. However, the lack of an accepted standard for choosing between RN, CN, and PN for M0 RCC patients necessitates further investigation, particularly in studies targeting specific patient populations to optimize benefits. Determining the optimal treatment for M0 RCC patients is challenging due to the diversity in tumor biology and patient characteristics9. The relative benefits of PN versus RN and CN are not fully resolved, highlighting the need for evidence-based guidelines and personalized treatment approaches. Post-nephrectomy survival outcomes are influenced by a multitude of factors, including tumor stage, grade, and TNM states10. Developing a prognostic model that accurately predicts overall survival (OS) could inform treatment decisions and improve patient outcomes11.

In this study, we sought to characterize the population appropriate for nephrectomy based on SEER database, in which nephrectomy can be classified based on the extent of resection: PN with conserved nephron, CN with removal of renal parenchyma alone, and RN that includes simultaneous resection of the parenchyma, affected perirenal fascia, perirenal fat, and ureter. We also evaluated risk factors and established prognostic model predicting OS for M0 RCC patients. Our findings aim to contribute to the existing body of knowledge by providing insights into the optimal management strategies for M0 RCC patients and guiding clinical decision-making.

Materials and methods

Cohort selection

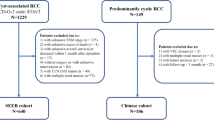

Patients in our study were obtained from the SEER database using the following selection criteria for patients undergoing RCC surgery:(1) malignant tumor primary site limited to the “kidney”; (2) no evidence of distant metastasis; (3) single primary cancer. Exclusion criteria were (1) age at diagnosis < 20 years; (2) unknown characteristics; (3) Pathologic subtypes that are not renal cell carcinoma under codes 8310–8319; (4) survival time < 30 days. Because publicly available data were used, no ethical approval or declaration was required in our study.

Data collection

We used SEER*Stat software version 8.4.3 (https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/download) to retrieve data (SEER Study data, 17 registry, November 2023–sub-2000-2021) for our study. All patient data collected included: marital status, race, sex, age, year of diagnosis, tumor laterality, histologic typ, primary site surgery, systemic therapy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, number of benign/borderline tumors, sarcomatoid features, primary tumor site, tumor size, grade, stage, T stage, N stage, cause of death, and survival outcomes. Data were converted to binary or categorical variables when necessary to comply with specifications.

Model construction

First, we calculated the survival indicators of RCC patients for 1/3/5/7/9 year respectively. For example, 1-year survival indicators, if the patient died within 1 year, it was marked as dead; if the patient survived after 1 year, it was marked as alive; if the follow-up time was less than 1 year and it was not marked as dead, the data was deleted. By this means, we obtained 54,033 (1-year), 52,795 (3-year), 48,071 (5-year), 40,349 (7-year), 34,215 (9-year) RCC patients respectively for model establishment, and randomly divided the training set and the test set according to 7:3 on the premise of ensuring data balance.

Autogluon models deep learning framework (https://github.com/autogluon/autogluon) was utilized to construct a prognostic model of RCC patients for surgical decision making. The implementation of surgical decision is as follows: We input the information of patients and assign the values of surgical methods as “None”,”PN”,”CN” and “RN” respectively to calculate the mortality rate. The surgical method with the lowest mortality rate is the operation with systematic decision. The code for the surgical decision is available on Github (https://github.com/minibelfast/RCC-surgical-decision-system).

Calculates feature importance scores for the given model via permutation importance. Refer to https://explained.ai/rf-importance/ for an explanation of permutation importance. The models were evaluated using Accuracy, Harrell’s Consistency Index (C-index), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, calibration curve and decision curve analysis (DCA)12 respectively.

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the association between clinical variables and survival. First, Cox univariate analysis was used to screen out the variables related to survival. Cox multivariate analysis was performed on the variables that passed the Cox univariate analysis to verify whether it was an independent prognostic factor. The variables that pass the Cox multivariate analysis will be incorporated into the deep learning model construction.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate survival. Cox regression analysis was used to determine the association between clinical variables and survival. Patients in the surgery group including none, PN, CN, and RN, or other groups, were matched using 1:1 propensity score matching (PSM) by Matching package and baseline tables before and after matching were provided. The data before and after matching were respectively drawn by Kaplan–Meier plots to obtain robust results.

Results

Univariate and multivariate COX regression analysis

A total of 56,534 RCC patients from 2004 to 2021 were obtained from the SEER database. Cox univariate analysis and Cox multivariate analysis were used to screen the influencing factors related to survival of M0 RCC patients. The results showed that marital status, race, sex, age, year of diagnosis, tumor laterality, histologic typ, primary site surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, sarcomatoid features, primary tumor site, tumor size, grade, T stage, N stage were independent prognostic factors for M0 RCC patients (Table 1).

From 2004 to 2021, both surgical and non-surgical treatment of RCC has changed significantly. Univariate COX analysis showed that patients with RCC had a better prognosis over time, but after 2018, the prognosis of patients became more volatile (Fig. 1a). One possibility is that although patients have more treatment options, how to choose treatment has become a challenge, and different treatment options lead to greater differences in prognosis outcomes. The year of diagnosis is an independent prognostic factor in patients with RCC (Fig. 1b). Surgery is still the mainstay of treatment options for patients with RCC, any nephrectomy in continuity with the resection of other organ, complete/total/simple nephrectomy, electrocautery, local tumor excision (NOS), partial or subtotal nephrectomy, radical nephrectomy, thermal ablation related to better survival of M0 RCC patients (Fig. 1c). Among them, only PN was an independent prognostic factor (Fig. 1d).

Benefits of radiotherapy and chemotherapy in M0 RCC patients

M0 RCC patients who received radiotherapy had a poorer prognosis in terms of CSS (Before PSM: HR = 8.51, 95%CI: 5.61–12.92, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 2.05, 95%CI: 1.57–2.67, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2a) and OS (Before PSM: HR = 4.77, 95%CI: 3.55–6.41, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 1.98, 95%CI: 1.55–2.54, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2b). M0 RCC patients who received chemotherapy had a poorer prognosis in terms of CSS (Before PSM: HR = 6.65, 95%CI: 5.45–8.11, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 1.84 95%CI: 1.58–2.15, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c) and OS (Before PSM: HR = 3.70, 95%CI: 3.21–4.26, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.27–1.68, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2d). Before and post-PSM baseline data are presented in Supplementary Table 1–8.

Benefits of different types of nephrectomy in M0 RCC patients

M0 RCC patients who received RN did not have a better prognosis in terms of CSS (Before PSM: HR = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.37–0.63, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 1.02, 95%CI: 0.75–1.39, p = 0.9) (Fig. 3a) and OS after PSM (Before PSM: HR = 0.63, 95%CI: 0.52–0.76, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 0.94, 95%CI: 0.74–1.19, p = 0.6) (Fig. 3b). M0 RCC patients who received CN did not have a better prognosis in terms of CSS (Before PSM: HR = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.12–0.23, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 1.40, 95%CI: 0.63–3.12, p = 0.41) (Fig. 3c) and OS after PSM (Before PSM: HR = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.49–0.74, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 1.18, 95%CI: 0.75–1.85, p = 0.46) (Fig. 3d). M0 RCC patients who received PN did not have a better prognosis in terms of CSS after PSM (Before PSM: HR = 0.09, 95%CI: 0.05–0.15, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 0.54 95%CI: 0.29–1.01, p = 0.055) (Fig. 3e) but had a better prognosis in terms of OS after PSM (Before PSM: HR = 0.26, 95%CI: 0.19–0.34, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 0.51, 95%CI: 0.34–0.76, p = 0.46) (Fig. 3f). Before and post-PSM baseline data are presented in Supplementary Table 9–20.

Subgroup analysis of M0 RCC patients with different types of nephrectomy

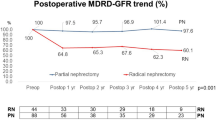

For the OS of all M0 RCC patients or N0M0 RCC patients, PN was significantly better than other surgical methods. When there was lymph node metastasis, the prognosis of PN patients did not show significant difference from other surgical methods, and the difference was large within the group (Fig. 4a). For the CSS of all M0 RCC patients or N0M0 RCC patients, the priority was PN, CN, RN, and None. It also indicated that PN patients did not have better prognosis, and the difference was large within the group when lymph node metastasis was present (Fig. 4b).

For OS and CSS in M0 RCC patients, PN was superior to CN and RN regardless of grade. But for grade I, None and PN did not show significant differences (Fig. 4c-d). For M0 RCC patients in grade I, surgical treatment should be considered more carefully. In terms of CSS and OS of M0 RCC patients, PN is better than other nephrectomy in all age groups (Supplementary Fig. 1a-b). In T1, T3, or T4 patients, the prognosis of PN patients was better than that of other nephrectomy patients, but the difference was not significant in T2 patients (Supplementary Fig. 1c-d). The prognosis of PN patients is better than that of other nephrectomy patients in all sex groups (Supplementary Fig. 1e-f).

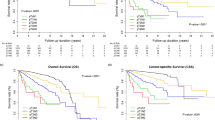

Stage I M0 RCC patients who received PN did not have a better prognosis than none surgery in terms of CSS (Before PSM: p = 0.4; After PSM: p = 0.19) (Fig. 5a) and OS after PSM (Before PSM: HR = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.31–1.75, p = 0.42; After PSM: HR = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.26–2.14, p = 0.57) (Fig. 5b). Stage I M0 RCC patients who received PN did not have a better prognosis than CN in terms of CSS (Before PSM: HR = 0.27, 95%CI: 0.11–0.67, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 0.74, 95%CI: 0.26–2.10, p = 0.57) (Fig. 5c) but had in terms of OS after PSM (Before PSM: HR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.23–0.46, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 0.61, 95%CI: 0.41–0.92, p = 0.019) (Fig. 5d). Stage I M0 RCC patients who received PN had a better prognosis in terms of CSS (Before PSM: HR = 0.23, 95%CI: 0.19–0.67, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 0.63 95%CI: 0.42–0.93, p = 0.021) (Fig. 5e) and OS after PSM (Before PSM: HR = 0.47, 95%CI: 0.43–0.53, p < 0.0001; After PSM: HR = 0.66, 95%CI: 0.56–0.78, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5f). Before and post-PSM baseline data are presented in Supplementary Table 21–32.

Kaplan Meier survival curve comparing CSS (a) and OS (b) in stage I M0 RCC patients with PN or none surgery. Kaplan Meier survival curve comparing CSS (c) and OS (d) in stage I M0 RCC patients with PN or CN. Kaplan Meier survival curve comparing CSS (e) and OS (f) in stage I M0 RCC patients with PN or RN.

Establishing a surgical decision model for M0 RCC patients using deep learning

Survival analyses have indicated that PN may confer potentially superior outcomes compared to other nephrectomy, and sometimes nephrectomy is not necessary. It is necessary to establishing a surgical decision model. As described in the Methods section, we counted 1/3/5/7/9 year survival information for M0 RCC patients and randomly divided them into training set and test set according to 7:3. Predictive model for 1/3/5/7/9 year survival in M0 RCC patients was developed using multiple deep learning methods, and their accuracy in the test set was measured (Fig. 6a). After training, we calculated the permutation importance of each variable. The top 5 variables were year of diagnosis, age, grade, tumor size, and T stage (Fig. 6b).

The model has a c-index close to 0.8 for predicting 1/3/5/7/9-year survival in both the train and test set, indicating good predictive ability (Fig. 6c–d). The ROC curve demonstrates that the model can balance true positive rate and false positive rate to a certain extent, showing a degree of robustness (Fig. 6e–f). The calibration curve illustrates good consistency between the model’s predicted probabilities and observed probabilities, with a slight elevation in the curve for 1/3-year survival prediction, possibly due to low mortality rates. However, some deviation is observed in the 9-year survival prediction (Fig. 6g–h). The DCA curve indicates a significant positive clinical benefit of the model (Fig. 6i–j). We then predicted the recommended treatment for all patients and based on this divided them into two groups that met the prediction and those that did not. The results found that patients who met the prediction group had a better survival prognosis than those who did not (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Discussion

In recent years, the advancement of precision medicine in RCC has necessitated a comprehensive understanding of the individual risks and benefits for each patient13,14. The increasing trend is to stratify patients based on disease attributes and predicted risk scores, thereby enhancing personalized care. Our study presents a surgical decision model that exhibits independent prognostic significance and has identified a particular advantage of PN for M0 RCC patients. While numerous prospective studies investigate the application of PN in M0 RCC across various stages, with no significant disparity in postoperative complications and survival between PN (216 cases) and RN (156 cases) in clinical T1 RCC15. The utilization of PN should be more judiciously considered for clinical T2 and clinical T3a RCC, taking into account specific patient characteristics as well as tumor factors16,17. Our model introduces a more granular evaluation by integrating stage and grade as determinants of surgical advantage, potentially facilitating more personalized treatment decisions. Indeed, the use of PN for M0 RCC remains heterogeneous, and the population should be more narrowly delineated18.

Furthermore, alongside the selection of the optimal surgical approach, the integration of surgery with additional treatment modalities constitutes a significant strategy for enhancing the prognosis of M0 RCC patients. Our findings suggest that the combined use of radiotherapy and chemotherapy with surgery may not significantly improve outcomes for M0 RCC patients. The refinement of surgical treatments and the establishment of benefit profiles for distinct patient subsets offer a more promising strategy than traditional multimodal therapy. Emerging studies, such as Hannan et al.'s work on the efficacy and safety of stereotactic ablative radiation for primary RCC19, suggest potential avenues for future research. Moreover, targeted therapies have shown promise for localized and locally advanced RCC5, although data limitations precluded further examination in our study.

From 2004 to 2020, there have been significant changes in the surgical and non-surgical treatments for M0 RCC patients, providing more treatment options. This serves as a limitation of the study, despite including the year of diagnosis as a covariate in the model. Other treatment modalities for RCC patients, such as percutaneous thermal ablation, may carry a higher risk of recurrence compared to robot-assisted partial nephrectomy20. stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy seems to be an effective and safe salvage strategy for this recurrent patient21. Additionally, Percutaneous cryoablation for cT1a RCC appears to be more cost-effective than PN22. These are intriguing areas for further exploration, which were not delved into deeply in our model.

To our knowledge, this is the inaugural surgical decision model for RCC patients that can assist patients in the choice of surgery. Nonetheless, the model retains certain limitations: there are few covariates available, it is a retrospective study, which makes avoiding selection bias difficult, and the sample size utilized for training is derived from a single cohort. Consequently, prospective clinical trials and additional external validations are imperative.

Conclusions

For OS and CSS in M0 RCC patients, PN was superior to CN and RN regardless of grade. But for grade I, PN and none surgery did not show significant differences. In order to further categorize surgical patients and make more precise decisions regarding their treatment, a surgical decision-making model has been established.

Data availability

The datasets analysed in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Linehan, W. M. & Ricketts, C. J. The Cancer Genome Atlas of renal cell carcinoma: Findings and clinical implications. Nat. Rev. Urol. 16, 539–552 (2019).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. Ca-a Cancer Journal for Clinicians 73, 17–48 (2023).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: Estimates for 40 countries and 25 major cancers in 2018. Eur. J. Cancer 103, 356–387 (2018).

Patel, H. D. et al. Clinical stage migration and survival for renal cell carcinoma in the United States. European Urology Oncology 2, 343–348 (2019).

Ingels, A. et al. Complementary roles of surgery and systemic treatment in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Urol. 19, 391–418 (2022).

Ljungberg, B. et al. European association of urology guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: The 2022 update. Eur. Urol. 82, 399–410 (2022).

Grabbert M, Grosu AL, Zamboglou C, Gratzke C: Nivolumab in Combination with Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy in Pretreated Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma. Results of the Phase II NIVES Study. European Urology 2022, 81:622–622.

Ryan, C. W. et al. Adjuvant everolimus after surgery for renal cell carcinoma (EVEREST): A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 402, 1043–1051 (2023).

Singla, N. Progress toward precision medicine in frontline treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 6, 25–26 (2020).

Ciccarese, C. et al. Post nephrectomy management of localized renal cell carcinoma. From risk stratification to therapeutic evidence in an evolving clinical scenario. Cancer Treat. Rev. 115, 102528 (2023).

Zhanghuang, C. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict cancer-specific survival in elderly patients with papillary renal cell carcinoma. Front. Public Health https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.874427 (2022).

Vickers, A. J. & Elkin, E. B. Decision curve analysis: A novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med. Decis. Making 26, 565–574 (2006).

Elias, R. et al. A renal cell carcinoma tumorgraft platform to advance precision medicine. Cell Reports 37(8), 110055 (2021).

Wu, Q. Y., Huang, G., Wei, W. J. & Liu, J. J. Molecular imaging of renal cell carcinoma in precision medicine. Mol. Pharm. 19(10), 3457–3470 (2022).

Luis-Cardo, A. et al. Laparoscopic nephron sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy in cT1 renal tumors. Comparative analysis of complications and survival. Actas Urologicas Espanolas 46, 340–347 (2022).

Mir, M. C. et al. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy for clinical T1b and T2 renal tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Eur. Urol. 71, 606–617 (2017).

Stout, T. E., Gellhaus, P. T., Tracy, C. R. & Steinberg, R. L. Robotic partial radical nephrectomy for clinical T3a tumors: A narrative review. J. Endourol. 37, 978–985 (2023).

Liu, N. et al. Nephron-sparing surgery for adult Xp11.2 translocation renal cell carcinoma at clinical t1 stage: A multicenter study in China. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 28, 1238–1246 (2021).

Hannan, R. et al. Phase 2 trial of stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for patients with renal cancer. Eur. Urol. 84(3), 275–286 (2023).

Pandolfo, S. D. et al. Percutaneous thermal ablation for cT1 renal mass in solitary kidney: A multicenter trifecta comparative analysis versus robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. Ejso 49, 486–490 (2023).

Ali, M. et al. Salvage stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy after thermal ablation of primary kidney cancer. BJU Int. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.16520 (2024).

Wu, X., Uhlig, J., Shuch, B. M., Uhlig, A. & Kim, H. S. Cost-effectiveness of minimally invasive partial nephrectomy and percutaneous cryoablation for cT1a renal cell carcinoma. Eur. Radiol. 33, 1801–1811 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We want to be grateful for the SEER database.

Funding

No funding in the present research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y. and X.W. designed this research. S.Y. organized the processing flow. S.Y. and X.W. completed the whole analytic process of this study. S.W. organized and presented the results. S.Y., X.W., and S. W. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. X.X. provided administrative and technical support. All authors reviewed the manuscript, agreeing with the publishing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Patient consent was waived due to this article using data from the SEER database, which are publicly available deidentified patient data from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), USA.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, S., Wang, X., Wang, S. et al. Impact of different nephrectomy types on M0 renal cell carcinoma outcomes in a propensity score matching and deep learning study. Sci Rep 14, 27571 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79070-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79070-2