Abstract

Additive manufacturing of metallic parts by Selective Laser Melting (SLM) implies high temperature gradients and small volume of the melt bath. These conditions make the process scales close to those available for state-of-the-art massively parallel atomistic simulations. In the paper, the microscopic mechanisms responsible for the formation of primary microstructure during molten metal solidification are investigated using classical molecular dynamics (CMD). The 316L austenitic stainless steel with face centred cubic lattice, which is widely used in industry including SLM applications was chosen as a material for the CMD simulations. It was shown that solidified material inherits substrate defects and catches new ones, which interact with the solidification front thus producing the primary microstructure. Peculiarities of solidification in different crystallographic directions and solidification front interaction with grain boundaries and newly produced defects (mostly twin boundaries) as well as their formation are under study. Resulting microstructures of virtual samples are compared with those of real samples produced by SLM and analysed by the electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) method. The comparison shows similarities of EBSD and CMD sample patterns and evidences for the capability of the large-scale atomistic simulations to reproduce main features of the microstructures formed in the metallic SLM additive production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Consumer quality of parts produced using additive manufacturing with Selective Laser Melting (SLM) is defined by the microstructure resulting from solidification conditions. One has to control the conditions in order to provide proper/required thermodynamical and mechanical properties of SLM produced parts. To influence the process of microstructure formation various regimes and techniques are used including ultrasonic and pulsed laser treatments. The review of the issues can be found in paper1.

For deeper understanding of processes taking place during crystallization, experimental investigations in the field are to be supplemented by numerical simulations. State-of-the-art massively parallel multimillion atomistic modeling is an effective way to unveil many significant aspects of crystal nucleation in molten metals and alloys2,3,4,5,6,7,8. CMD is capable to track and quantify the microscopic mechanisms responsible for the formation of primary microstructures during solidification in the conditions of high temperature gradients9,10,11,12 as well as the microstructure evolution at high temperatures proper to the initial stages of just crystallized material cooling13.

As a model system for the investigation into defect structure formation during crystallization of molten metal we used a model austenitic alloy Fe-14Ni-19.5Cr (Ni and Cr concentrations are in weight percent) as an imitation of stainless steel 316L that is widely used in industry including additive manufacturing. The nominal chemical composition of 316L austenitic steel can be found in paper14. Minor alloying elements besides Ni and Cr in our model composition were equally distributed as Ni and Cr atoms. All CMD simulations were carried out with the Finnis-Sinclair type interatomic potential15 that provides the crystallization of the overcooled melt Fe-14Ni-19.5Cr into face centered cubic (fcc) lattice with Ni and Cr atoms distributed as disordered substitutional solution.

The system is characterized by very small difference between solidus and liquidus temperatures14 and so one can speak of melting temperature. The ambient pressure melting point parameters for the used interatomic potential15 and chemical composition were calculated here with two independent techniques, namely, the Thermodynamic Integration Method (TIM)16,17 in the formulation by Freitas et al.18 and the modified Z-method19,20 with essentially coinciding results. Calculated parameters at the ambient pressure melting point are presented in Table 1 in comparison with experimental data14 measured for NIST Standard Reference Material (SRM). One can see that used interatomic potential reproduces melting parameters of 316L steel quite well, excluding perhaps the volume change, but the parameter is not crucial for the current investigation, and stacking fault energy the effect of which is discussed hereafter.

All CMD simulations were carried out with massively-parallel CMD code LAMMPS21,22,23. For sample structure analysis we used Polyhedral Template Matching (PTM)24 method implemented in scientific data visualization and analysis software for atomistic simulations, OVITO25,26,27 and Adaptive Template Analysis (ATA)28 that allows precise, high confidence recognition of crystal structures and various defects in samples at elevated temperatures up to the melting point.

In the frames of current study the following issues are of interest: 1) velocity of the crystallization front as dependent on the degree of overcooling and mutual orientations of the front and the growing crystal lattice; 2) formation of lattice defects during the crystallization as dependent on the degree of overcooling and mutual orientations of the front and the growing crystal; 3) interaction of the solidification front with ingrain defects and with grain boundaries leading to the formation of the primary microstructure.

Isolated crystal nucleus growth

In the current section we focus on the CMD simulations of grow process of an isolated quasi-spherical fcc crystal nucleus placed in overcooled liquid. A cubic system of \(\sim 4\) million atoms with the size of \(\sim 37~{\text {nm}}\) was prepared for the modeling. The system was kept at nearly zero pressure and constant temperature with Nose-Hoover thermostat and barostat29,30. In the molten sample, an fcc crystallite with initial diameter about \(\sim 20\) percent of the box size was placed to form the crystallization front close to spherical one. In this case the crystallization in all crystallographic directions is realised and due to different crystallization rates in different directions the shape of growing crystal transforms with time. Figure 1 illustrates stages of the crystal nucleus growth at different degrees of overcooling. Grain orientation colouring at \(t=800~{\text {ps}}\) for each temperature (right column) was done using PTM analysis24. Defect structures are seen to form when overcooling is high, i.e. the crystallite growth is fast, whereas a pure fcc crystal (almost free of defects) grows when the crystallization proceeds slowly.

Stages in the simulation of fcc nucleus growth in austenitic model Fe–14Ni–19.5Cr alloy with the potential15 at different degrees of overcooling. A sections of the system are shown. Green color is for fcc atoms and red is for hcp atoms. Grain orientation colouring at \(t=800~{\text {ps}}\) for each temperature (right column) was done using PTM analysis24.

Figure 2 presents a defect structure formed during crystallization at a constant temperature of about \(\sim 0.7946T_m\). The semitransparent green surface shows the boundary of the growing austenite crystal with surrounding liquid. The red color is used to highlight atoms of the hcp structure, which form twinning planes in fact. As one can see, crystallization does not reproduce the perfect fcc structure of the nucleus. Note here that the formation of twins in metals with low stacking fault energies was observed in MD simulations previously, for example, the issue was discussed in2. Analysis of the growing crystallite structure revealed mixture of two types of twinning: lamellar one and five-fold-twinning with well predominance of the former. These types of twinning were already observed in pure fcc metals (see6 and7). In6 the lamellar structure very similar to that in Fig. 2 was called nested tetrahedral lamellar. Note that the lamellar twinning is formed in plane system \(\left\{ 111\right\}\) only.

Presented here results show that even in ideal conditions there are some microscopic mechanisms of defects generation in the growing crystal nucleus. But the homogeneous nucleation is not realized in practice. As a rule, the solidification takes place on a substrate two types of which are considered hereafter.

Defect structure of fcc nucleus growing in austenitic model Fe–14Ni–19.5Cr alloy during crystallization at a constant temperature of \(1400~{\text {K}}\approx 0.7946T_m\). The semitransparent green surface is the boundary of the growing fcc crystal with surrounding liquid. Red color shows the atoms of the hcp structure (twin boundaries) determined with OVITO25,26,27.

Solidification on single-crystal substrate

he crystallization is accompanied with the local release of heat that should be properly dissolved in the sample. That is why the calculations were done with the account for electron heat conductivity by using the Two-Temperature Model (TTM) by Duffy and Rutherford31,32 implemented in LAMMPS. The use of the TTM allows us to take into account electron heat transfer which becomes important for the case of high rate crystallization regimes considered here. The parameters of the TTM used in the simulations are presented in Table 2. The procedure of the parameters tuning for the model Fe-14Ni-19.5Cr alloy to be published elsewhere.

he effect of the TTM is shown in Fig. 3. Here the simulation is carried out with the sample of about 300 nm length. Left and right sample boundaries are kept at \(T=1600{\text {K}}\). Temperature distribution near the solidification front in the simulation without the TTM shows much higher temperature peak due to slow heat transfer out of the thin front region. The velocity of the crystallization front is also affected by electron heat transfer that accelerates the front. Note also that when the TTM is applied the crystallization actually takes place at \(T=1675{\text {K}}\) due to local heat release. Without the TTM actual temperature of the crystallization is much higher.

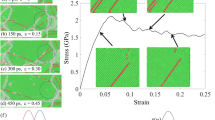

For quantitative defect formation analysis during solidification with quasi-plane crystallization front we performed calculations for systems of sizes \(\sim 12~{\text {mn}} \times \sim 12~{\text {nm}} \times \sim 65~{\text {nm}}\) elongated in one of the directions with periodic boundary conditions in all directions. The samples consisted of differently oriented fcc crystals narrowed by melted material (see Fig. 4a). The samples were kept at nearly zero pressure and temperature of \(\sim 0.7378T_m\).

Figure 4b shows structures formed after crystallization in the samples with the lattices differently oriented relative to the liquid/crystal interface for the crystallographic directions \(\left[ 001\right]\), \(\left[ 011\right]\), \(\left[ 111\right]\), \(\left[ 221\right]\) normal to the front, and the pseudo-arbitrary direction \(\left[ 4~17~\bar{5}\right]\)). One can see that the defect structure with twins forms in strongly overcooled samples if only crystallization occurs in the direction \(\left[ 111\right]\). ue to periodic boundary conditions and elongated samples with small cross-sections the front of the crystallization is plane and once born the twin boundaries cut through the entire samples cross-section. As it is shown hereafter in the case of larger samples the behaviour is more complicated.

The defect structures that form during crystal growth in different crystallographic directions at temperature \(T=1300~{\text {K}}\approx 0.7378 T_m\) and nearly zero pressure. (a) initial model sample. (b) defect structures after crystallization in different crystallographic directions determined with OVITO25,26,27.

To determine the average distance between the forming defects (\(\left\{ 111\right\}\) twinning planes), we performed simulations for samples which were strongly extended along the z axis, \(\sim 12~{\text {nm}} \times ~\sim 12~{\text {nm}} \times \sim 630~{\text {nm}}\) in size, and consisted of \(\sim 7.4\) million atoms. The simulations were done for several temperatures of overcooling (see Fig. 5). Sample elongation in the direction of crystallization allows collecting better statistics to estimate distances between the defects. For better statistics we also performed ten statistically independent CMD simulations for each temperature. The systems were kept at nearly zero pressure. Crystal growth proceeded during up to \(10~{\text {ns}}\) for the highest temperature of \(1700~{\text {K}}\approx 0.9648T_m\) with registration of plane defects and estimation of the mean distance between the twinning planes and its standard deviation at different temperatures, i.e. at different velocities of the crystallization front (see Fig. 6). In the CMD simulations we determined also how the velocity of the crystallization front depends on the degree of overcooling and the direction of the crystallization (see Fig. 7). One can see that the crystallization front velocity vs. overcooling dependence demonstrates noticeable anisotropy.

ormation of the \(\left\{ 111\right\}\) twinning planes during rapid crystallization of strongly overcooled molten Ni as well as the microscopic mechanism responsible for twins formation were reported and analysed in paper33. Proposed there model of the twinning planes origin derives critical temperature \(T_c\) above which according to33 the formation of the twins is impossible. The formulae for \(T_c\) is as follows \(T_c\approx T_m(1-\gamma _{twin}/\Delta H_f h)\) where \(T_m\) is melting temperature, \(\gamma _{twin}\approx 0.5\gamma\) is approximately half of stacking fault energy, \(\Delta H_f\) is heat of melting, and h is the spacing between the \(\left\{ 111\right\}\) planes in the fcc lattice. Substituting parameters from Table 1, the critical temperature may be evaluated as \(T_c\approx 0.86T_m\). But as it is seen from Fig. 6 the twins form well above this temperature, but the probability of their formation rapidly decreases with the increase of temperature. Thus, the theory of twin formation suggested in33 needs minor improvement. The immediate correction is to change \(\Delta H_f\) used as a coefficient in linear dependence of Gibbs potentials difference between solid and liquid phases \(\Delta G=\Delta H_f(1-T/T_m)\) for proper coefficient that can be easily determined from TIM calculations as \(550~{\text {J}}/{\text {g}}\) (instead of \(\Delta H_f=287~{\text {J}}/{\text {g}}\)). So, the corrected value of critical temperature \(T^*_c\approx 0.93T_m\) is in much better agreement with result of current MD simulations (see Fig. 6) keeping in mind actually the more than twice lower energy of twins as compared to the stacking faults33.

Assuming stochastic character of the twinning origin one may suppose that the probability of their formation at given temperature is proportional to solidification front surface. Then the characteristic scale of twin domains (distance between twin planes) is determine by two factors: the degree of overcooling \(1-T/T_m\) and the CMD sample cross-section. At first glance it would be easy to estimate the characteristic size of domains for arbitrary size sample crystallizing in \(\{111\}\) direction at given temperature, just dividing the value taken from Fig. 6 by the ratio of the sample cross-section areas \(S/S_0\). To check the hypothesis the simulations were carried out with much larger samples at \(T=0.95T_m\). As one can see in Fig. 8a at the larger scale of sample the solidification front is not plane and gets some hilly shape. The “hills” interrupt twinning plane growth. On the other hand the simulations showed the role of forming twinning planes in the shaping of the solidification front. As one can see in Fig. 8b,c because the twinning planes do not cut through the entire sample from left to right a number of vertical neighbouring twins were formed and solidification front gets additional curvature. This shape of the solidification front may be explained from the thermodynamics point of view by minimization of excess free energy with respect to grain boundary (vertical boundary between neighboring twins) and solidification front areas. Diminishing of the grain boundary area (decrease of its excess free energy) leads to the increase of the curvature of the solidification front and the increase of its area (increase of its excess free energy). The equilibrium configuration corresponds to convex shape of the solidification front with overall decrease of excess free energy. Thus, the scale of the twins depends on the rate of solidification (degree of overcooling) and spectrum of the solidification front perturbations. Resulting twin patterns obtained in CMD simulations for \(T=0.90T_m\) and \(0.95T_m\) are presented in Fig. 9a,b.

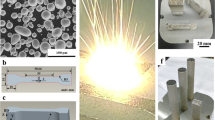

arge-scale atomistic modeling is currently not capable of giving direct results for overcooling of several degrees (front velocities are about \(\lesssim 1~{\text {m}}/{\text {s}}\)) realizing in the SLM additive production. Note here that in MD simulations3 front velocities of about \(0.1~{\text {m}}/{\text {s}}\) were reliably fixed, but the samples were quite small. In so-called large-scale MD simulations involving about \(\sim 10^8\) atoms and nano-second timescale one needs to increase overcooling and front velocities to meet reasonable computation time. Nevertheless it would be interesting to compare the results of large-scale CMD simulations with the microstructure of real SLM produced samples. To do that a number of samples were printed and then examined with electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) technique. For SLM manufactured samples the powder of 316L austenitic stainless steel was used. The particle sizes and shape were analyzed by scanning electron microscope (SEM) Phenom Pro X. The powder consisted of fractions from 10 to \(63~\mu {\text {m}}\) that have a spherical shape with a certain number of satellites. SLM device uses an Yb-fiber laser with \(1070~{\text {nm}}\) wavelength. The laser power was varied in the range of 100 to \(500~{\text {W}}\). Sample synthesis was carried out on the building platform made of 316L stainless steel. The typical parameters of scanning strategies are as follow: laser power – \(300~{\text {W}}\), layer thickness – \(40~\mu {\text {m}}\), scanning velocity – \(800~{\text {mm}}/{\text {s}}\), laser spot size – \(80~\mu {\text {m}}\), hatch distance – \(50~\mu {\text {m}}\).

Automated analysis of EBSD patterns was performed with the TESCAN VEGA LMH scanning electron microscope with the LaB6 cathode with the Oxford Instruments Advanced AZtecEnergy X-ray energy dispersion microanalysis system and the EBSD NordLysMax2 Oxford Instruments attachment with AZtec version 3.5 software. For material and phase identification, we used the Oxford Instruments database of pure and organic materials, and the NIST database of phases and elements. Scanning step was \(0.05~\mu {\text {m}}\).

The comparison of microstructures of virtual CMD and real samples is presented in Fig. 9 as EBSD images. The pattern of the sub-microstructure of SLM produced samples is very similar to that in virtual samples taking into account scale corrections with respect to the front velocities. In Fig. 9 presented results of the CMD simulation at \(T=0.9T_m\) (Fig. 9a) and \(T=0.95T_m\) (Fig. 9b) and corresponding twins scale is \(\sim 20~{\text {nm}}\) and \(\sim 50~{\text {nm}}\). In EBSD images of SLM produced samples the characteristic twin scale is about several microns.

(a) Demonstration of the effect of forming nano-twins on the shape of solidification front (green color is for the fcc structure atoms, red color is for hcp structure (twinning planes) atoms, grey color is for amorphous (liquid) structure); (b) and (c) growing neighbour twins (color refers to crystal orientation in (b), only defects are shown in (c)).

Solidification on polycrystalline substrate

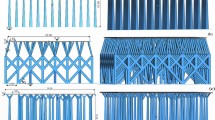

The described above peculiarities of crystallization at different relative orientations of the solidification front and the crystal lattice must affect the microstructure when crystallization takes place on a polycrystalline substrate. Indeed, different velocities of the crystallization front lead to the preferred growth of particular grains. The CMD simulations of the crystallization on a polycrystalline substrate were carried out with two types of CMD samples: the quasi 2D sample which had dimensions of \(\sim 37~{\text {mn}}\times \sim 150~{\text {nm}}\times 278~{\text {nm}}\) (\(\sim 120\) million atoms) and initially contained three columnar monocrystalline grains of arbitrary orientation (all grain boundaries are vertical in the beginning) as a solid substrate (see Fig. 10); and with full 3D sample which had dimensions \(\sim 100~{\text {nm}}\times ~\sim 100~{\text {nm}}\times \sim 308~{\text {nm}}\) (\(\sim 236\) million atoms) and contained initially four grains quasi-rectangular in the xy cross section (see Fig. 11). Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all directions in both cases. Temperature in 2D and 3D simulations was kept at 0.95 of \(T_m\).

Results of the simulations are presented in Figs. 10 and 11. One can see that as the solidification advances, the initially vertical grain boundaries bend right or left (see Fig. 10) depending on the relative growth rate of neighboring grains. The direction of the inclination is toward a grain, which has the lower growth rate. The bigger difference in growth rates between neighbor grains, the bigger inclination. Compare the growth of grains marked as \(\#~2\) and \(\#~3\) in Fig. 10. In the upper and lower parts of Fig. 10 these grains have the same initial mutual orientation because they are images across the periodic boundary conditions. After the formation of twins in grain \(\#\) 2 they again have the same mutual orientation in the upper and lower parts of the sample. However, in the lower part of Fig. 10 it is seen that the grain boundary between grains \(\#~2\) and \(\#~3\) inclines toward grain \(\#~2\), while in the upper part the inclination is toward grain \(\#~3\). Note here that the orientation of crystals relative to solidification front in the vicinity of triple junction point is of importance. Due to local curvature and orientation of the front relative to crystal lattice, the adjacent grains with the same mutual orientation may grow with different relative rates.

The formation of twins while grains growing also leads to the grain boundary turn that is quite well seen in Fig. 10. The ongoing process of crystallization creates a flake-like primary microstructure because for some grains their columnar growth proved to be terminated by joined neighbor grains as one might expect for grain \(\#~3\). The process of the crystallization in full 3D is presented in Fig. 11. One can see that the expected columnar structure is broken by the twinning and anisotropy of crystal growth, and the formation of a druse-like structure is in progress. The lower row of snapshots allow to estimate the distance from the substrate where the grain structure of the substrate is forgotten. The distance is about several substrate grain size. Moreover the competing growth of grains lead to the survival of most rapidly growing grains and as a consequence to similar lattice orientation relative to the solidification front in neighbour grains. Different growth rate of grains as dependent on their orientation dominates among factors affecting solidification font shape and is responsible for the most coarse substructure. Twinning also causes different growth rate but the effect is not so strong and reveals itself at smaller scale.

Summary

Results presented in the paper demonstrate the capabilities of state-of-the art molecular dynamics simulations to track the formation of primary microstructure at high temperature gradients proper to SLM metal additive productions. It was shown that primary microstructure is determined by the rate of crystallization, i.e. by the degree of overcooling realizing in the vicinity of the solidification front. One may suppose that twins formation is determined by the properties of a thin layer nearby the crystallization front that may differ from those of the liquid and the solid. The microscopic mechanisms of the twins generation will be the subject of further investigation and will be presented in the following paper. The average size of nano-twins can be used as an indicator of the solidification front speed. Formation of the twins is also depends on orientation of crystal relative to solidification front. These sub-microstructure features are to be most sensitive to changes of solidification conditions and thus it is possible to manage its formation during SLM by changing laser speed and intensity. Together with mechanical effect of pulsed laser or ultrasound (see paper1) resulting in plastic deformations of low-strength just crystallized material the factors affecting the sub-microstructure may prove to be an effective instruments for managing final mechanical properties of items produced with SLM.

Additional information

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to V.V.D.

References

Ivanov, I. A. et al. Effect of laser-induced ultrasound treatment on material structure in laser surface treatment for selective laser melting applications. Sci. Rep. 11, 23501. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02895-8 (2021).

Mendelev, M. I., Rahman, M. J., Hoyt, J. J. & Asta, M. Molecular-dynamics study of solid-liquid interface migration in fcc metals. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 074002. https://doi.org/10.1088/0965-0393/18/7/074002 (2010).

Winlson, S. R. & Mendelev, M. I. Anisotropy of the solid-liquid interface properties of the NI-ZR B33 phase from molecular dynamics simulation. Phil. Mag. 95(2), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786435.2014.995742 (2015).

Sun, Y. et al. Overcoming the time limitation in molecular dynamics simulation of crystal nucleation: A persistent-embryo approach. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 085703. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.085703 (2018).

Mahata, A., Zaeem, M. A. & Baskes, M. I. Understanding homogeneous nucleation in solidification of aluminum by molecular dynamics simulations. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 26, 025007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-651X/aa9f36 (2018).

Zahiri, A. H., Chakraborty, P., Wang, Y. & Cao, L. Strong strain hardening in ultrafast melt-quenched nanocrystalline Cu: The role of fivefold twins. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 075103. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5110287 (2019).

Wu, Y. et al. A new crystallization pattern of nested tetrahedral lamellar structure for the face-centered cubic metals with low stacking fault energy. Scr. Mater. 186, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2020.04.031 (2020).

Kavousi, S. & Asle Zaeem, M. Mechanisms of nucleation and defect growth in undercooled melt containing oxide clusters. Acta Mater. 252, 118942. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118942 (2023).

Mahata, A. & Asle Zaeem, M. Effects of solidification defects on nanoscale mechanical properties of rapid directionally solidified Al-Cu alloy: A large scale molecular dynamics study. J. Cryst. Growth 527, 125255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2019.125255 (2019).

Singh, G., Waas, A. M. & Sundararaghavan, V. Understanding defect structures in nanoscale metal additive manufacturing via molecular dynamics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 200, 110807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2021.110807 (2021).

Kumar, S. et al. Atomistic characterization of multi nano-crystal formation process in Fe-Cr-Ni alloy during directional solidification: Perspective to the additive manufacturing. Mater. Chem. Phys. 308, 128242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2023.128242 (2023).

Kavousi, S., Ankudinov, V., Galenko, P. K. & Asle Zaeem, M. Atomistic-informed kinetic phase-field modeling of non-equilibrium crystal growth during rapid solidification. Acta Mater. 253, 118960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118960 (2023).

Dremov, V. V., Chirkov, P. V. & Karavaev, A. V. Molecular dynamics study of the effect of extended ingrain defects on grain growth kinetics in nanocrystalline copper. Sci. Rep. 11, 934. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79861-3 (2021).

Pichler, P., Simonds, B. J., Sowards, J. W. & Pottlacher, G. Measurements of thermophysical properties of solid and liquid NIST SRM 316L stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. 55, 4081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-019-04261-6 (2020).

NIST Interatomic Potentials Repository. https://www.ctcms.nist.gov/potentials/entry/2019--Mendelev-M-I--Fe-Ni-Cr/2019--Mendelev-M-I--Fe-Ni-Cr--LAMMPS--ipr1.html.

Frenkel, D. & Ladd, A. J. C. New Monte Carlo method to compute the free energy of arbitrary solids application to the fcc and hcp phases of hard spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3188. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.448024 (1984).

Frenkel, D. Free energy computation and first-order phase transitions. In Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Statistical Mechanics Systems, XCVII, 151–188 (Soc. Italiana di Fisica, 1986).

Freitas, R., Asta, M. & de Koning, M. Nonequilibrium free-energy calculation of solids using LAMMPS. Comput. Mater. Sci. 112, 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2015.10.050 (2016).

Wang, S., Zhang, G., Liu, H. & Song, H. Modified Z method to calculate melting curve by molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 138, 134101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4798225 (2013).

Karavaev, A. V., Dremov, V. V. & Pravishkina, T. A. Precise calculation of melting curves by molecular dynamics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 124, 134101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.commatsci.2016.08.014 (2016).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1006/jcph.1995.1039 (1995).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS—a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpc.2021.108171 (2022).

LAMMPS Molecular Dynamics Simulator. http://lammps.org/.

Larsen, P. M., Schmidt, S. & Schiotz, J. Robust structural identification via polyhedral template matching. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 24, 055007. https://doi.org/10.1088/0965-0393/24/5/055007 (2016).

Stukowski, A. & Albe, K. Extracting dislocations and non-dislocation crystal defects from atomistic simulation data. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012. https://doi.org/10.1088/0965-0393/18/8/085001 (2010).

Stukowski, A. Computational analysis methods in atomistic modeling of crystals. J. Metals 66, 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11837-013-0827-5 (2014).

OVITO - Open Visualization Tool - Scientific data visualization and analysis software for atomistic simulation models in materials science and related disciplines. http://www.ovito.org/.

Sapozhnikov, F. A., Ionov, G. V. & Dremov, V. V. An adaptive template method for analyzing crystal structures and defects in molecular dynamics simulations of high-rate deformations. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2, 238–245. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1990793108020115 (2008).

Nose, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 511–519. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.447334 (1984).

Hoover, W. G. Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1697. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.31.1695 (1985).

Duffy, D. M. & Rutherford, A. M. Including of the effects of electronic stopping and electron-ion interactions in radiation damage simulations. J. Phys. Condenced Matter 19, 016207. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/19/1/016207 (2006).

Rutherford, A. M. & Duffy, D. M. The effect of electron-ion interaction on radiation damage simulations. J. Phys. Condenced Matter 19, 496201. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/19/49/496201 (2007).

Sedao, X. et al. Growth twinning and generation of high-frequency surface nanostructures in ultrafast laser-induced transient melting and resolidification. ACS Nano 10, 6995–7007. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.6b02970 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Grant number MT-96 under the EOTP Rosatom research program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.V.D. conceived CMD simulations, contributed to the discussion, and wrote the manuscript. P.V.C. and R.M.K. performed CMD simulations, carried out analysis of CMD samples, visualized the results, and contributed to the discussion. A.V.K. performed CMD simulations, analyzed the results, and contributed to the discussion and writing of the manuscript. I.A.I., V.S.D., S.V.S. supervised the project and were responsible for conceptualizing the project goals, as well as contributed to the discussion. E.B.C. conceptualized and supervised the experiments, contributed to the discussions and writing of the manuscript. V.V.Ch. conducted the EBSD study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dremov, V.V., Chirkov, P.V., Kichigin, R.M. et al. Atomistic simulation of primary microstructure formation in metals during crystallization from the melt. Sci Rep 14, 28105 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79228-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79228-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Molecular dynamics simulation and analysis of pre-crystallization layer between liquid and solid states

Scientific Reports (2025)