Abstract

The negative inference that consumers hold ‘eavesdropping’ views concerning the intelligent recommendation services of digital platforms is fostering their selective exposure to information that aligns with their preferred viewpoints. This, in turn, exacerbates their psychological defense against digital platforms, causing consumers to become more prone to verifying existing beliefs and fostering the polarization of information choices. This phenomenon directly impacts the effectiveness of smart recommendations and the accuracy of digital platforms’ predictions of consumer behavior, potentially even adversely affecting brand trust and the long-term stability of platform usage. From the perspectives of self-verification and cognitive closure, this study delves into the influence of ‘eavesdropping’ inference cues within intelligent recommendation systems on consumers’ selective exposure to information and the underlying psychological mechanisms. Experimental findings indicated: (1) Behavioral results showed that consumers who believed in eavesdropping by digital platforms, under conditions of high comprehensibility, were more inclined to selectively engage with consistent information as opposed to inconsistent information. Under conditions of low comprehensibility, however, information consistency had no significant effect on consumers’ selective exposure. (2) EEG results revealed that, based on the need for cognitive closure, individuals in the high comprehensibility group, during the self-verification process, exhibited more cognitive conflict and required greater cognitive effort when presented with inconsistent information compared to those in the consistent information group. This, in turn, elicited higher N2 and N450 amplitudes. This study uncovered the psychological mechanism underlying this phenomenon. When consumers developed a skeptical perspective on perceived eavesdropping by digital platforms within intelligent recommendation systems, they promptly engaged in self-verification, driven by the need for cognitive closure. The study’s findings offered practical guidance to digital platforms on how to alleviate consumer suspicions when designing intelligent recommendation services, thereby mitigating negative consumer reactions to the perception of ‘eavesdropping’. This insight held significant theoretical and practical value at the intersection of digital marketing and psychology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the era of digital intelligence, consumers are increasingly inclined to believe that digital platforms engage in ‘eavesdropping.’ These platforms utilize emerging technologies, including AI intelligent algorithms, sound wave recognition, data sharing, and semantic analysis, to comprehensively monitor and ‘peek’ at consumers’ ‘digital footprints’1,2. Consequently, they are able to accurately ‘peer’ into the true intrinsic needs of consumers3,4. For instance, the phenomenon of immediately receiving relevant advertisements recommended by platforms shortly after a conversation has led to consumers having strong suspicions that their personal information and privacy may be being ‘eavesdropped’ upon5. Due to lack of awareness of the underlying principles of judgment algorithms and corresponding knowledge barriers, once consumers form a suspicion of platform “eavesdropping” upon encountering new developments, they are more inclined to believe in this viewpoint. Once consumers suspect that a platform is ‘eavesdropping’, their trust and loyalty to the digital platform will be directly weakened. This suspicion can affect user activity, impact the platform’s user base and market competitiveness through word-of-mouth communication, and even prompt consumers to switch to services offering stronger privacy protection, thereby intensifying market competition. At the same time, it deeply reflects consumers’ concerns about personal privacy and data security. These concerns not only alter online behavior patterns but also induce widespread social psychological effects, such as anxiety and distrust, reducing their satisfaction with the online experience and making them more inclined to seek information that aligns with their own views6. Consumers’ preference for information that supports their own views not only leads to miscalculations but also hinders the robust development of the digital ecosystem7. Therefore, exploring consumers’ perceptions of ‘eavesdropping’ and their underlying psychological mechanisms is of great significance. This can provide practical guidance for digital platforms to optimize their strategies, enhance user trust, and ensure privacy and security.

Faced with intelligent algorithm recommendations, consumers are more convinced that platforms engage in eavesdropping and prefer to choose information that aligns with their own attitudes. This tendency of consumers is called “selective exposure”8. Reviewing existing research on selective exposure, scholars have developed dominant explanatory frameworks like cognitive dissonance theory8, information utility9, and motivation inference theory10 from the perspective of cognitive motivation. They suggest that factors such as source credibility9, information usefulness11, and the inconsistency of information lead consumers to develop more aversion motivation and selectively choose information consistent with their own attitudes8. Despite these literature interpretations of selective exposure from various perspectives, they have overlooked that in immediate online decision-making contexts, due to consumers’ cognitive limitations and knowledge barriers concerning algorithmic recommendations and related technologies, consumers cannot seek truth based on accuracy motivation (explain supplementary material appendix). Inconsistent information from algorithm recommendations may not induce dissonance in consumers4,12. In immediate online decision-making, based on confirmatory motivation (explain supplementary material appendix), consumers are more likely to verify their prior beliefs and preferences according to differences in the understandability of information regarding “eavesdropping.” Moreover, constrained by the research paradigms and measurement methods used, existing studies have mostly relied on self-reports to study selective exposure. In addition, due to the research paradigms and measurement methods adopted, most existing studies use self-report to study selective contact, so that the acquired data are retrospectively processed by the brain (explain supplementary material appendix). However, consumer selective exposure to information is an immediate online behavior, and traditional research methods cannot accurately reflect the formation of individual selective attention in real-time, nor can they obtain direct evidence of physiological electrical signals (explain supplementary material appendix) in the brain processing during selective exposure.

To address the limitations of prior research, this study focuses on individual self-verification and the need for cognitive closure. The cognitive closure theory pertains to the tendency of individuals to swiftly form judgments and seek cognitive closure in ambiguous or uncertain situations, driven by the need for certainty and conclusion13. Meanwhile, the self-verification theory states that individuals possess a motive to maintain and verify the consistency of their self-concept, tending to seek out and interpret information that aligns with their self-image. Building on these two theories, individuals tend to seek information that aligns with their own concepts while ignoring or rejecting information that contradicts their viewpoints, in order to verify and consolidate their self-concept. By categorizing the “presence or absence of eavesdropping” inference cues into information comprehensibility and consistency, the study deeply explores the underlying mechanisms of consumers’ selective exposure to information. Simultaneously, by utilizing high-temporal resolution event-related potentials (ERPs) technology14,15, researchers can capture real-time electroencephalogram (EEG) data during consumers’ selective exposure to information16. By analyzing specific mental processes through objective physiological electrical signal indicators, the study associates consumers’ instant attitude (explain supplementary material appendix) formation and current selective exposure, revealing how they are interconnected. This approach both aligns with the research context of online consumers and enables an in-depth analysis of the cognitive processing “black box” of consumers regarding the inference cues related to the existence of eavesdropping. The study offers empirical evidence to validate consumers’ suspicion of emerging technologies and broadens the application scope of self-verification and the theory of the need for cognitive closure.

Literature review and hypothesis deduction

Relevant review

Early studies found that individuals tend to seek information that supports rather than contradicts their own attitudes. Following the discovery of this phenomenon, Festinger et al.17 termed it “selective exposure,” defining it as a preference for information consistent with existing attitudes, beliefs, and decisions or a tendency to disregard information inconsistent with them. Currently, selective exposure is widely used in various research fields. For example, in investment decisions, investors are more inclined to expect positive investment information, and thus are more willing to accept positive investment information18,19. During interrogations, police officers tend to consider suspects as actual criminals, leading to instances of misjudgment20. In intelligent recommendations, selective exposure has also garnered widespread attention in academia. For instance, in the adoption of word-of-mouth, consumers perceive comments that align with their initial beliefs as more helpful21. In the selection of political information, voters are more willing to engage with news that supports their own stance10,22,23.

Selective exposure to information is influenced by various factors. Such as information sources24, information presentation order4, and information quantity25. Research by Turcotte et al.26 revealed that individuals find news sources with consistent or neutral attitudes to be more credible than those with inconsistent attitudes, and they are more willing to spend more time on sources and content consistent with their prior attitudes10. Wojcieszak11 found based on the similarity of recommended information sources that individuals prefer to browse useful and politically consistent content the mechanisms explaining selective exposure differ when individuals are presented with consistent versus inconsistent information23,24. For instance, when the quantity of recommended information is increased, individuals become more stringent in reviewing inconsistent information, only reducing their perceived quality, thus increasing selective exposure25. Conversely, when the attractiveness of information sources is increased, individuals only enhance their evaluation of the quality of consistent information, thereby increasing selective exposure25,27.

In summary, existing research places greater emphasis on the influence of characteristics such as information sources and quality, with less exploration into the impact of information comprehensibility on selective exposure. In realistic situations, when people harbor suspicions of “eavesdropping” by intelligent recommendation platforms, there is significantly different comprehensibility regarding consistent and inconsistent information. For instance, viewpoints with low comprehensibility regarding eavesdropping often involve aspects of the internet, algorithmic recommendation associated technologies that people are less familiar with, whereas high comprehensibility viewpoints generally align with people’s existing logic and cognition of suspicion. However, existing research has addressed the impact of the comprehensibility of “presence or absence of eavesdropping” inference clues on selective exposure to a lesser extent. Hence, further investigation into the intrinsic impact of the information comprehensibility of “presence or absence of eavesdropping” inference clues on individual decision-making is crucial for big data platforms to instantly grasp consumer preferences regarding suspicions of “presence or absence of eavesdropping,” and how to reduce such suspicions.

Behavioral hypothesis

Information comprehensibility refers to the individual’s understanding of the referent (i.e., suspicions of platform eavesdropping) and is related to the individual’s knowledge base and past experiences28. Defining high comprehensibility as a clearer and more specific representation of information, it is easier to retrieve and understand5. Such information can be quickly retrieved from working memory and is therefore more likely to generate concrete schemas29,30,31, for example, secrets about microphone activation. Defining low comprehensibility as representing information with abstract and relatively holistic features32, the information is more complex and difficult to understand, and individuals cannot quickly form schemas from past experiences31, such as browsing components of Dries analysis or intelligent positioning data of Yicui.

Because consumers cannot discern the intrinsic processing principles of emerging technologies and the corresponding knowledge barriers30,33, in the face of platform “eavesdropping” issues, people, driven by a need for cognitive closure, are eager to make judgments to eliminate uncertainty34,35. Once consumers form the view on platform “eavesdropping,” they are more inclined to believe it. When consumers face the “eavesdropping” view, they engage in heuristic processing driven by the need for cognitive closure, swiftly processing and encountering consistent information to achieve closure, while disregarding subsequent inconsistent information34. Due to consumers’ lack of corresponding knowledge reserves, consumers are unable to seek truth based on accuracy motives31. Therefore, in instant online decision-making, consumers are more inclined to rely on confirmation motives36 to validate pre-existing assumptions or beliefs. Specifically, when information elements are simpler and more easily readable, consistent information is more supportive compared to inconsistent information31. Individuals with confirmation motives are more inclined to engage with consistent information in order to validate their own viewpoints37. When faced with complex and incomprehensible information, due to lower comprehensibility and diagnostic capability, consumers show no significant difference in selective exposure to consistent and inconsistent information. To sum up, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1: Information comprehensibility and consistency exert an influence on consumers’ selective exposure to information. Specifically, when information is highly comprehensible, consumers are more likely to selectively expose themselves to information that aligns with their own views. Conversely, in situations of low information comprehensibility, differences in information consistency have no significant impact on consumers’ selective exposure.

Event-related potentials and corresponding hypotheses

Cognitive closure needs are often considered as a cognitive motive. Considering its short-term fluctuating nature, this study reflects individual cognitive processes related to cognitive closure needs through N2 and N450 components. Literature generally contends that N2 is related to conflict monitoring and cognitive conflict, and plays an important role in cognitive and behavioral decision-making. The N2 component is distributed in the frontocentral joint area and central area, with a latency period between 250-350ms, particularly sensitive to conflict monitoring. Perez-Osorio et al.38. used N2 component as an indicator of cognitive conflict when humans processed inconsistent signals given by robots. Experiments showed that when the robot’s head turned in the wrong direction (i.e. inconsistent signals), the participants’ N2 amplitude was higher, and the inconsistent signals caused higher cognitive conflict, indicating that the brain detected the mismatch between expectation and reality. For example, when participants saw text with mismatched color and vocabulary (e.g., when the word ' red ' was shown as blue), the magnitude of N2 increased, reflecting participants ' attempts to suppress automatic word-reading responses to focus on color. The enhancement of this component indicates the individual ‘s detection of conflict and the initiation of cognitive control. High-conflict situations can induce more negative N2 components than low-conflict situations39. In studies of behavioral decision-making, the greater the cognitive conflict individuals experience in decision-making, the greater the N2 amplitude elicited. Compared to consistent information, high comprehensibility inconsistent information contradicts individuals’ prior assumptions, possessing stronger perceptual diagnostic power, leading to greater perceived conflict and a higher risk of attitude change. Based on confirmation motives, individuals in a state of cognitive closure need are more sensitive to conflict perception, which can induce a greater N2 amplitude40, thus avoiding inconsistent information. Under conditions of low comprehensibility, due to lower readability, individuals have lower diagnosticity for refutational information and are less likely to experience conflict perception. Consequently, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2: The amplitude of the N2 component induced by individuals differs based on the comprehensibility and consistency of information. Specifically, when information is highly comprehensible, individuals exposed to inconsistent information exhibit a higher N2 amplitude. Conversely, under conditions of low comprehensibility, differences in information consistency have no significant impact on the N2 amplitude induced by individuals.

N450 is a late brain electrical component located in the medial and lateral prefrontal cortex, with a latency of around 450 milliseconds41. N450 is typically associated with individual cognitive control, and the higher the degree of cognitive control over a target, the higher the induced N45042. Rauchbauer et al.43. employed the N450 component as an indicator of individuals’ proficiency in exercising cognitive control during social-emotional imitation tasks. When participants were exposed to inconsistent hand movements and emotional facial stimuli, the amplitude of the N450 component increased significantly. This finding suggests that inconsistent stimuli elicit a heightened level of cognitive control. Our results highlight the crucial role of cognitive control mechanisms in managing automatic imitation in social contexts, particularly when confronted with conflicting information. Cognitive control refers to an individual’s ability to inhibit task-irrelevant information when engaging in goal-directed behavior44. Studies indicate that in problem-solving and reasoning processes, individuals need to rapidly identify task-relevant information using perception and memory, while controlling or inhibiting irrelevant information, in order to solve problems more effectively through cognitive control45,46. Scholars have found that due to differences in individuals’ cognitive resource allocation, there are different information preferences under varying cognitive closure needs47. Specifically, high comprehensibility inconsistency contradicts individuals’ prior assumptions and beliefs more than consistent information, triggering negative experiences and threatening individuals’ needs. Based on confirmation motives, individuals in a state of cognitive closure need utilize more cognitive resources to control or suppress belief violation brought about by inconsistent information, consciously seek and use information that aligns with their viewpoints. In conclusion, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3: The amplitude of the N450 component induced by individuals differs based on the comprehensibility and consistency of the information presented. Specifically, when individuals have high comprehensibility of the information but encounter inconsistency, they exhibit higher volatility in the N450 amplitude. Conversely, at low levels of comprehensibility, differences in information consistency have no significant impact on the N450 amplitude induced by individuals.

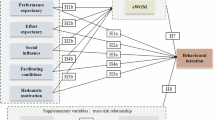

Figure 1 shows the research model of this study:

Pre-experiment

Experimental design

The purpose of the pre-experiment is to verify consumers’ inclination to believe in the viewpoint that smart recommendation platforms eavesdrop. The study first measures the extent of consumers’ attitudes regarding the belief that smart recommendation platforms eavesdrop. Before the experiment, researchers inform participants about situations in which others have developed suspicions after receiving smart ad recommendations. For example, “I saw a roadside stall selling inflatable pools, I was quite interested so I enquired about the price and indicated my intention to purchase. Later, when I opened Taobao, the ‘recommended for you’ section bombarded me with numerous inflatable swimming pools! Since I have never searched for or browsed such items on any app, how did this happen? I started to suspect that the digital platform is eavesdropping on my conversations…”.

Subsequently, researchers measured participants’ attitude certainty using two questions (1= “not confident at all,” 7= “completely confident”, α = 0.76)48: (1) How confident are you in the idea that “smart advertising is based on eavesdropping”? (2) To what extent do you believe that the viewpoint “businesses make smart recommendations using eavesdropping methods” is correct? As a result variable of the study, to examine consumers’ attitude certainty towards the “eavesdropping” viewpoint on platforms. Furthermore, related studies confirm the impact of attitude importance and attitude contradictoriness on selective exposure to information49,50. To ensure that stimulus materials do not evoke differing metacognitive cognitive responses in trial participants with regard to suspicions about “eavesdropping,” researchers simultaneously measured attitude importance (α = 0.81): (1) To what extent is the viewpoint “businesses make smart recommendations using eavesdropping methods” important to you? (1= “not important at all,” 7= “extremely important”) (2) To what extent does the viewpoint “businesses make smart recommendations using eavesdropping methods” affect your values or beliefs? (1= “not at all,” 7= “to a great extent”), with attitude contradictoriness (1= “totally contradictory,” 7= “completely in line”, α = 0.86): (1) Do you hold contradictory views regarding the viewpoint “businesses make smart recommendations using eavesdropping methods”? (2) Do you experience contradictory emotions about the viewpoint “businesses make precise recommendations using eavesdropping methods”?

Experimental results

Manipulation test. Controlling for variables, the study employed a one-way independent samples t-test, indicating no significant difference in attitude importance scores between the two groups, t(22) = 3.67, p > 0.05; nor were there significant differences in attitude contradictoriness scores; t(22) = 8.31, p > 0.05. This suggests that the stimulus materials did not elicit differences in participants’ attitudes towards importance and contradictoriness.

The study used a one-factor independent sample t-test, with the results showing significant differences in individuals’ attitudes towards the “eavesdropping” perspective on digital platforms (M = 5.62, SD = 1.09), (M = 3.33, SD = 1.47), t(22) = 4.34, p < 0.001. The study used an independent sample t-test, revealing that higher attitude certainty is associated with increased selectivity in information exposure (M=-0.23, SD = 0.66), t(22) = 2.97, p < 0.001.

Preliminary experiments have demonstrated that in the age of digitalization, once consumers develop the viewpoint of “eavesdropping” on intelligent recommendation platforms, they tend to choose to engage with information consistent with their own views or beliefs. Based on this, the present study conducted the subsequent experiment to further explore the intrinsic cognitive process of selective exposure under varying information intelligibility and consistency, investigating how individuals engage in self-verification regarding the skeptical viewpoint of eavesdropping on platforms to reinforce prior beliefs and viewpoints, and examining the cognitive processing involved in this self-verification process. This question will be addressed in the following experiment.

Formal experiment

Experiment methodology

Participants selection

The study initially used G*power3.1 to calculate the required sample size for EEG research51, using repeated measures ANOVA as the measurement method. The parameters were set as follows: Repeated measures, within-between interaction, Effect size f = 0.25, α = 0.05, Power (1-β) = 0.8, Number of groups = 2, Number of measurements = 6, Correlation between repeated measures = 0.5, resulting in a sample size of 19 individuals. In total, 24 college students (41.67% male, Mage = 24) took part in the experiment, all of whom had also participated in the preliminary experiment. All participants had normal or corrected vision, were non-colorblind, right-handed, free from mental illnesses or organic diseases, had not previously taken part in a similar experiment, and would be compensated after the experiment. This study employed a 2 (Information comprehensibility: high vs. low) × 2 (Information consistency: consistent vs. inconsistent) mixed experimental design.

Experimental materials and design

(1) Information comprehensibility.

The experiment materials involved the selection of 30 pieces of “eavesdropping” suspected information by the researchers, followed by inviting 30 university students to individually rate the comprehensibility of these 30 pieces of information (1 = completely incomprehensible, 5 = very comprehensible). After the pretest, the 30 pieces of information were split through a bisection method into high comprehensibility and low comprehensibility categories. Post-hoc tests indicated that the high comprehensibility scores were significantly higher than the low comprehensibility scores; t(28) = 11.298, p < 0.001.

Next, we further designed the experimental materials using the Stroop task paradigm, specifically by presenting each type of information in either red or blue ink. The purpose of designing these experimental materials was to investigate the cognitive interference component N2 and the cognitive control component N450 triggered by the meaning of the information as an attentional interference while individuals were engaged in a color discrimination task for the information. Such modified Stroop paradigms have been utilized in numerous studies measuring selective exposure, for instance Yang et al.52 used altruistic and egoistic information to construct modified Stroop materials, investigating people’s cognitive control towards altruistic and egoistic information by measuring N450. Li et al.48 employed refusal words, acceptance words, and neutral words to create modified Stroop materials, probing attentional biases towards relevant information through the measurement of N2 and N450 differences.

(2) Selective exposure.

Building upon the pilot study, researchers informed the participants of the research scenario as shown in Fig. 2. For example, “Just as I was talking with a friend about wanting to eat durian cake, I received a push advertisement for durian cake on my mobile app. I had never searched for anything similar before. The platform must have been eavesdropping on me.” After understanding the research scenario, the researchers presented views related to eavesdropping suspicion using the E-prime program, requesting participants to react to the color of the views. Simultaneously, the researchers used the Neuroscan instrument to record participants’ brain responses during the decision-making process. Following the Stroop experiment, the researchers measured selective exposure to information according to methods outlined by Strien et al.53 and Deng et al.21. Specifically, the researchers asked the participants to answer questions regarding selective exposure to information for tasks of high comprehensibility and low comprehensibility, where incongruent information for high comprehensibility tasks represented high comprehensibility information, and incongruent information for low comprehensibility tasks represented low comprehensibility information, with congruent information being the same for both high and low comprehensibility tasks. In both tasks, participants were asked to select up to 5 points for further reading from a total of 8 views on this topic event (4 congruent and 4 incongruent views). Subsequently, the difference between the number of congruent and incongruent information chosen by the participants was divided by the total number of chosen information, serving as the score for selectivity of information exposure, ranging from − 1 (complete absence of selective exposure) to 1 (complete selective exposure).

Experimental procedure

The experiment consists of a practice phase and a formal experimental phase, as shown in Fig. 3. The purpose of the practice phase is to familiarize the subjects with the experimental procedures and operations.

-

1.

Practice phase.

In the practice phase, 8 neutral sentences (not present in the formal phase) are selected and presented randomly. The subjects are required to respond to the color of the written words with a key press, and this part will provide feedback on the correctness of the key press. The relationship between the keys on the keyboard and the colors is: red color corresponds to the F key, and blue color corresponds to the J key, with a total of 8 trials in the practice phase.

-

2.

Formal phase.

After practice, press the Q key to start the formal experiment. Initially, a “+” fixation point is presented in the center of the computer screen for 600ms. Subsequently, viewpoints with colors randomly appear on the screen, such as “Eavesdropping behavior is bound by privacy terms, not eavesdropping possible”, “Inter-layer edge differential clustering algorithm calculation, not eavesdropping"… Each statement is displayed for 2000ms, followed by a blank screen for 500ms before moving to the next trial; subjects are required to react to the color of the vocabulary with a key press, including a total of 60 trials.

Collection and processing of experimental data

Utilizing the American NeuroScan EEG recording and analysis system, electrode placement is based on the 64-channel electrode cap expansion of the internationally standard 10–20 system. Simultaneously recording vertical eye movement (VEO) and horizontal eye movement (HOE). The bandpass filtering is set at 0.01–100 Hz, with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz; the scalp impedance is required to be less than 5kΩ. Data processing steps include artifact removal, baseline correction, and grand averaging. The time segment is 1000ms, with the 200ms period before the stimulus serving as the baseline time. With reference to the research of relevant scholars38,39,40,43,45, selecting the N2 brainwave component time window: 220-320ms, with electrode analysis at F1, FZ, F2, FC1, FCZ, FC2. N450 brainwave component time window: 400-500ms, with electrode analysis at F1, FZ, F2, FC1, FCZ, FC2. Greenhouse-Geisser correction is employed. Performing repeated measures analysis of variance on the wave amplitude of N2 and N450 components, with information comprehensibility as the between-group factor and information consistency as the within-group factor.

Results

Behavioral results

Using analysis of variance, the results indicate a significant main effect of the interaction between information comprehensibility and information consistency F(1, 44) = 19.82, p < 0.001. Under conditions of high information comprehensibility: the selective contact score of the information-consistent group (M = 0.52, SD = 0.51) is significantly higher than that of the information-inconsistent group (M=-0.63, SD = 0.52), t(22) = 2.53, p < 0.001. Under conditions of low information comprehensibility: there is no significant difference between the selective contact scores of the information-consistent group (M M = 0.07, SD = 0.37) and the information-inconsistent group (M = 0.18, SD = 0.53), t(22) = 0.01, p > 0.05. Detailed information can be found in Table 1.

Behavioral data results reveal that under conditions of high information comprehensibility, individuals in the consistent information group exhibit higher scores of selective exposure compared to the inconsistent information group, whereas under conditions of low information comprehensibility, there is no significant difference in the scores of selective exposure between individuals in the inconsistent and consistent information groups. This is due to consumers’ lack of cognitive grasp of the underlying principles of judgment algorithms and the existence of corresponding knowledge barriers. Faced with the issue of platform “eavesdropping,” individuals, driven by cognitive closure needs, urgently seek to make judgments to eliminate uncertainty. Once individuals form the “eavesdropping” perspective, the lack of specialized knowledge in intelligent recommendation algorithms compels them to place even greater trust in their previous viewpoints for self-validation. Specifically, in the group with more understandable information, individuals are more likely to make judgments and rapidly validate their own viewpoints when faced with inconsistent information, thus confirming hypotheses 1.

EEG results

Utilizing ERPs technology, this study aims to capture the instantaneous cognitive responses of online consumers during the decision-making process. Its primary advantage lies in its high time sensitivity, enabling an accurate reflection of cognitive changes at the millisecond level. This aligns well with the rapid scrolling behavior observed in online consumption scenarios on mobile phones, accurately simulating the real-time decision-making of online consumers. In contrast to traditional questionnaires, ERPs technology does not require consumers to spend an extended period contemplating, thereby avoiding cognitive biases stemming from deliberation. This ensures both the internal and external validity of the research. By observing changes in the N2 and N450 components through ERPs technology, this study aims to uncover the underlying cognitive mechanisms of consumers’ real-time online decision-making.

N2 component

Repeated measures ANOVA conducted on the N2 component using a 2 (information comprehensibility: high vs. low) × 2 (information consistency: consistent vs. inconsistent) × 6 (electrode sites: F1, FZ, F2, FC1, FCZ, FC2) design reveals that the main effect of information comprehensibility is marginally significant, F(1, 22) = 23.74, p = 0.08, the main effect of information consistency is not significant, F(1, 22) = 0.10, p = 0.75, the interaction effect between information comprehensibility and information consistency is significant, F(1, 22) = 12.17, p < 0.001, the main effect of electrode sites is significant, F(1, 22) = 5.49, p = 0.003, showing no interaction effect between information comprehensibility and electrode sites, F(1, 22) = 0.64, p = 0.68, and no interaction effect between information consistency and electrode sites, F(1, 22) = 0.44, p = 0.82.

Under high information comprehensibility conditions, the N2 wave amplitude energy (M=-0.23, SD = 0.29) of the inconsistent information group is significantly higher than that of the consistent information group(M = 2.78, SD = 0.21), F(1, 11) = 5.40, p = 0.03. This demonstrates that in the realm of online marketing, consumers harbor doubts about the reliability of information on digital platforms within a short span of time, and this phenomenon occurs swiftly and is challenging to detect. Consequently, the information recommended by digital platforms ought to be consistent. In the event of any inconsistency, clear, explicit background explanations and recommendation rationales should be furnished to aid consumers in understanding, thereby mitigating their doubts regarding ‘eavesdropping’ and preventing the accumulation of such doubts among consumers. The main effect of electrode sites is significant, F(5, 7) = 35.78, P < 0.001, and there is a significant interaction effect between information comprehensibility and electrode sites, F(5, 11) = 158.31, p < 0.001.

In the condition of low information comprehensibility, there is no significant difference in N2 wave amplitude energy (M = 0.76, SD = 0.54) between the inconsistent information group and the consistent information group (M = 2.20, SD = 0.31), F(1, 11) = 1.06, p = 0.32. When information is difficult to comprehend, consumers’ judgment becomes limited, making them potentially less sensitive to changes in the consistency of that information. However, it is advisable to refrain from using vague privacy policy statements, as they may exacerbate consumer suspicion and unease. The main effect of electrode sites is significant, F(5, 7) = 33.20, P < 0.001, and there is a significant interaction effect between information comprehensibility and electrode sites, F(5, 7) = 318.40, p < 0.001. As shown in Fig. 4.

The high and low comprehensibility groups exhibit N2 component amplitude. Different colors are used to distinguish varying levels of information comprehensibility and consistency. The horizontal axis represents time, while the vertical axis depicts the potential amplitude. The light gray section illustrates the trend of intelligibility and consistency for different information over time, at six electrode points (F1, FZ, F2, FC1, FCZ, FC2) within the 220–320 millisecond time window.

N450 component

Repeated measures analysis of variance on N450 component with 2 (information comprehensibility: high vs. low) × 2 (information consistency: consistent vs. inconsistent) × 6 (Electrode Sites: F1, FZ, F2, FC1, FCZ, FC2) reveals a significant main effect of comprehensibility, F(1, 22) = 18.87, p < 0.001, a non-significant main effect of consistency, F(1, 22) = 1.74, p = 0.20, a significant interaction effect between comprehensibility and consistency, F(1, 22) = 5.68, p < 0.001, a significant main effect of electrode sites, F(1, 22) = 6.01, p = 0.002, no interaction effect between comprehensibility and electrode sites, F(1, 22) = 1.22, p = 0.34, and no interaction effect between consistency and electrode sites, F(1, 22) = 1.03, p = 0.43.

Under conditions of high comprehension: The N450 waveform energy of the inconsistent information group (M=-3.13, SD = 0.29) is significantly higher than that of the consistent information group (M = 2.45, SD = 0.21), F(1, 11) = 24.69, p < 0.001. It demonstrates that when information is easily understandable, consumers exhibit a greater cognitive effort when confronted with information inconsistency, resulting in increased attention and suspicion towards the information due to its violation of individuals’ preconceived assumptions and viewpoints. Consequently, when crafting recommendations, digital platforms should guarantee the consistency of the recommended content. In the event of inconsistency in the recommended information, the pertinent background and rationale behind the recommendation should be elucidated to the consumer, assisting them in forming expectations.

The main effect of electrode sites is significant, F(5, 18) = 5.78, P < 0.01, while the interaction between comprehension and electrode sites is not significant, F(5, 18) = 0.77, p > 0.05. Under conditions of low comprehension: There is a significant difference between the N450 waveform energy of the inconsistent information group (M=-1.44, SD = 0.54) and the consistent information group (M = 2.81, SD = 0.31), F(1, 11) = 7.23, p < 0.001. See Fig. 5. This suggests that when information is low in intelligibility, despite the persistence of differences between the two groups, consumers’ responses are less pronounced compared to scenarios of high intelligibility, hinting that the complexity of information may impair individual judgment ability. Digital platforms ought to ensure that recommended content is straightforward and easily comprehensible, refraining from the use of intricate terminology and expressions, thereby enabling consumers to swiftly grasp the information and alleviate cognitive load. Additionally, they should explicitly outline the data usage and privacy protection measures, steering clear of vague statements.

Amplitude of N450 component in consistent and inconsistent conditions for high and low comprehensibility groups. Different colors are utilized to differentiate varying levels of information comprehensibility and consistency. The horizontal axis signifies time, whereas the vertical axis represents the potential amplitude. The light gray section depicts the trend in intelligibility and consistency of various information over time, recorded at six electrode points (F1, FZ, F2, FC1, FCZ, FC2) during the 400–500 millisecond time window.

Based on EEG data, individuals were found to exhibit higher N2 and N450 amplitudes in the inconsistent information condition compared to the consistent information condition under conditions of high comprehensibility, reflecting the need for cognitive closure during the self-verification process. Results suggest that incongruent information under conditions of high comprehensibility challenges individuals’ prior assumptions and beliefs, eliciting negative experiences, which in turn threaten personal needs and lead to increased psychological discomfort and cognitive conflict. Furthermore, individuals exhibiting cognitive closure needs invest additional cognitive resources to regulate belief violation stemming from incongruent information. Under low comprehensibility conditions, individuals may experience delayed early cognitive arousal, necessitating increased cognitive effort to suppress belief violation from incongruent information regarding further “eavesdropping” analysis. Hypotheses 2 and hypotheses 3 were supported, while hypothesis 3 provided contradictory conclusions.

Discussion

Conclusion

This study revealed through two experiments (a pilot study and a formal experiment) that consumers hold a strong belief in the existence of ‘eavesdropping’ on smart recommendation platforms. This suggests that, in the absence of professional knowledge about the relevant smart recommendation algorithms, consumers are more inclined to engage with viewpoints that align with their own. The pilot study confirmed that consumers exhibit high attitude certainty regarding the ‘eavesdropping’ viewpoint on smart recommendation platforms; the higher the level of attitude certainty, the more they tend to selectively engage with information.

Utilizing self-verification theory and cognitive closure need theory, this study elucidates the internal cognitive processes of consumers’ self-verification within the context of intelligent recommendation platforms. Behavioral data indicate that, under conditions of high information comprehensibility, consistent information significantly enhances individual selective contact compared to inconsistent information, thereby reflecting the tendency towards self-verification driven by cognitive closure needs. These findings were further substantiated by the presence of N2 and N450 components in EEG data. Based on the need for cognitive closure, during the process of self-verification, inconsistent information elicits greater N2 and N450 fluctuations compared to consistent information under conditions of high information comprehensibility. This may be attributed to the early detection and processing of conflicting information by the individual’s brain, thereby inducing increased cognitive conflict and effort. However, under conditions of low information comprehensibility, there was no significant difference in amplitude between the two groups, which aligns with the result showing no significant difference in scores between the two groups in the behavioral data. These EEG data findings not only confirm the hypothesis derived from the behavioral data but also uncover the neural mechanisms underlying the brain’s processing of the comprehensibility and consistency of diverse messages, thereby reinforcing the overall narrative of the study. By integrating behavioral and EEG data, the study offers a deeper insight into the cognitive and neural dynamics during information processing. In summary, this study establishes that under smart recommendations, both information comprehensibility and information consistency jointly impact consumers’ self-verification.

Theoretical contributions

This study makes several contributions. Firstly, it explores the impact of information comprehensibility and information consistency on consumers’ selective engagement from a self-verification perspective, providing new explanatory mechanisms for both. In the field of selective information engagement under smart recommendations, scholars have predominantly focused on factors such as the credibility of information sources9, the usefulness of information11, and the discomfort caused by incongruent information leading consumers to selectively engage with information consistent with their own attitudes for self-verification4,12. However, in real-life situations, once consumers form a skeptical attitude towards the “eavesdropping” of platforms, there exist significant differences in the comprehensibility of information related to different viewpoints. For instance, the eavesdropping viewpoint with low comprehensibility often involves specialized knowledge content in algorithmic recommendation technology that consumers may not fully understand, whereas the eavesdropping viewpoint with high comprehensibility typically aligns with consumers’ existing cognitive suspicions and is more readily accessible and understandable. Yet, existing studies have paid scant attention to the impact of the comprehensibility of cues inferring the presence or absence of eavesdropping on selective engagement. Consequently, this study, from a self-verification perspective, explores the combined effect of information comprehensibility and information consistency on selective engagement, considering the differences in comprehensibility that consumers face when confronted with the eavesdropping viewpoint of smart recommendation platforms. This simultaneous approach aligns with the real-life situations of consumers in information selective engagement, while also offering a new direction for existing research on information selective engagement.

Secondly, this study, based on the self-verification theory and the cognitive closure needs theory, extended their applicability to the realm of selective information engagement and privacy. Existing research has mostly focused on cognitive dissonance theory8, information utility9, and motivated reasoning theory10, suggesting that exposure to incongruent information leads consumers to generate more aversion motivation. In order to avoid psychological discomfort, consumers selectively engage with information consistent with their own viewpoints. However, constrained by existing theories, the research paradigm is “a hypothetical response to a hypothetical situation,” and behavioral decisions resulting from retrospective brain processing do not correspond to actual consumer behavior16. In real-life online situations, due to consumers’ cognitive limitations and lack of expertise in related technologies such as algorithm recommendations, consumers are unable to seek the truth based on accuracy motivation. Instead, they are more inclined towards confirmation motivation and cognitive closure needs. To dispel this uncertainty, they urgently make judgments based on the differences in the comprehensibility of information related to the viewpoint of platform “eavesdropping,” subsequently confirming information consistent with their prior beliefs and preferences. Therefore, this study, through the self-verification theory and cognitive closure needs theory, using ERPs technology, explores consumers’ cognitive processes in selective information engagement, combining their information processing features. Based on self-verification and cognitive closure needs, the study further investigates the mechanism of the impact of information comprehensibility and information consistency on consumers’ selective engagement, thereby expanding the applicability of self-verification theory and cognitive closure needs theory in research on selective information engagement and privacy.

Finally, this study adopts event-related potential (ERP) technology to provide new empirical methods for future experimental research on the cognitive mechanism of consumers’ selective engagement with online information. The traditional research methods rely on introspective and retrospective tools to measure consumers’ cognitive processing, but researchers find it difficult to understand consumers’ intrinsic cognitive processes based on self-verification in real time and their cognitive closure needs. This paper, from a neurophysiological perspective, uses electroencephalogram (EEG) signal analysis to explore the intrinsic mechanisms of how information comprehensibility and information consistency influence consumers’ selective information engagement, offering a better assessment of consumers’ cognitive conflicts and cognitive control processes from the perspectives of confirmation motivation and cognitive closure needs. Direct acquisition of physiological electrical signals from consumers’ brains allows for real-time measurement of their cognitive and emotional responses14,15,54, effectively reducing potential biases caused by subjective data in traditional research methods, and provides an initial attempt to open the “black box” of consumer cognitive processing, laying the groundwork for future studies.

Marketing insights

In the era of digital intelligence, with the frequent occurrences of privacy breaches and digital abuse events, consumers develop negative inferences towards intelligent recommendation services offered by digital platforms. For instance, if consumers believe that digital platforms are “eavesdropping,” it will intensify consumers’ distrust and resistance towards digital platforms and companies, consequently leading to serious negative impacts on the digital platform’s image and future strategic development. The findings of this research have the following implications for digital platforms.

Over-exploiting consumers’ latent needs under intelligent recommendations is sometimes inadvisable. Digital platforms often believe that instantaneously uncovering consumers’ real psychological needs would increase their satisfaction with products and services, while ignoring the serious negative impact of immediately recommending related advertisements to consumers under intelligent recommendations. According to the conclusion of this study, when consumers receive corresponding advertisements recommended by digital platforms as soon as they utter something, they become convinced that the platform is eavesdropping. Once consumers form this perception, they are more likely to selectively engage with information consistent with their own views and are unwilling to engage with information that contradicts their views. In other words, the more convinced consumers are, the more they prefer to believe that digital platforms adopt eavesdropping and other unreasonable means to profit. To mitigate this adverse effect, digital platforms inform consumers about the legitimacy of their access to information via transparency measures such as privacy policies and statements, but it is more important for digital platforms to decrease the level of conviction consumers have in the eavesdropping suspicion, for example, by promoting authoritative views from multiple channels and using scientific experiments to enhance the persuasiveness of information. These methods can reduce the level of certainty consumers have in their eavesdropping suspicions, thereby reducing selective information engagement. At the same time, if consumers perceive the platform as ‘eavesdropping’, the consistency of information should be reduced when the comprehensibility is low, in order to prevent stimulating consumer prejudice. In summary, enterprises should incorporate the findings of this study into their real-time strategy adjustments, flexibly alter the timing and content of recommendations, and alleviate consumers’ suspicions of eavesdropping on digital platforms. This will not only maintain consumer trust but also optimize the recommendation effect, achieving a win-win situation.

Furthermore, the study found that the comprehensibility and consistency of information regarding the perception of “eavesdropping” on digital platforms jointly influence consumers’ selective engagement behavior. That is, under high information comprehensibility, consumers are more inclined to selectively engage with consistent information compared to inconsistent information. When developing and designing information retrieval systems, digital platforms should consider differences in consumers’ comprehension of information when dealing with relevant negative information and providing explanations. For consumers who are convinced of the existence of eavesdropping by digital platforms, under conditions of high information comprehensibility, digital platforms should provide professional knowledge such as algorithm-recommended related technologies to break down the barriers of knowledge related to internet technologies, AI algorithms used in consumer portraits, enabling consumers to further understand the intrinsic application principles of emerging technologies, change consumers’ suspicions about the existence of “eavesdropping” by digital platforms, and increase their willingness to use digital platforms. At the same time, digital platforms and enterprises should use more information that is easily read and understood by consumers, for example, related to the illegality of eavesdropping and the limitations of eavesdropping costs, allowing consumers to quickly understand, internalize, which is more conducive to improving the effectiveness of explanations by digital platforms and enterprises.

Finally, digital platforms and businesses should strive to avoid triggering negative cognitive responses in consumers as much as possible. This study found that under conditions of high information comprehensibility, consumers exhibit more cognitive conflict and effort, leading to higher N2 and N450 amplitudes when faced with inconsistent information compared to consistent information. Due to the lack of knowledge about algorithm recommendation technology, once consumers form the “eavesdropping” viewpoint, they urgently seek validation for their own perspectives. Faced with inconsistent information that contradicts prior beliefs and understanding, consumers experience significant internal cognitive conflict. Based on confirmatory motivation, consumers use more cognitive resources to control belief violation brought about by inconsistent information. Therefore, in the design of content for precise advertising disclosures or privacy terms, digital platforms and businesses should fully consider the differences in consumers’ cognitive motivations and cognitive closure needs. To reduce consumer suspicion, the recommendation system ought to provide clear and timely recommendation information, facilitating consumers’ quick decision-making. Considering the variations in conflict and control among diverse cognitive motivations and needs, the system should employ more pertinent information that consumers can readily comprehend, devise a concise and intuitive interface, emphasize the rationale and foundation of recommendations, and bolster the credibility and persuasiveness of the information. Furthermore, it is imperative to account for individual differences and offer personalized recommendation strategies tailored to different consumers’ cognitive closure needs. For instance, for consumers with a high demand for closure, more definitive recommendation results can be presented; whereas for those with a lower demand for closure, a more diversified array of choices can be provided.

Limitations and future prospects

Firstly, this study primarily sampled university and graduate students. Although college students constitute the primary force within the current consumer group, there are still limitations to consider, including factors such as age, culture, concepts, and background. Future research should endeavor to incorporate these diverse groups into the sample scope, for instance, by examining the potential impact of individuals’ perceptions regarding privacy and eavesdropping under different cultural contexts on a global scale. This approach will render the research conclusions more generalizable and convincing. Secondly, limited by the EEG experimental method, this study only considered the impact of information comprehensibility and consistency on consumer selective exposure. Additionally, the material was designed to be relatively straightforward, which differs somewhat from the labeling and layout of information in online searches. Future studies could expand on this research foundation by delving more deeply. For instance, by using the impact of information framing for “story marketing” and influencing consumer information processing through time constraints and quantity restrictions. The topic discussed is ‘The potential impact of consumers’ familiarity with digital platforms on their cognitive response to eavesdropping. Future research could further explore the intrinsic impact of these factors on selective information exposure and expand the experimental materials. Thirdly, the study used EEG experimental methods, primarily focusing on the micro-cognitive mechanisms of information comprehensibility and consistency related to selective exposure. The scale of the study was relatively small. Subsequent studies might attempt large-scale experiments or secondary data methods to expand the external validity of the research.

Data availability

The data are available upon request due to privacy or ethical restrictions. The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Dylko, I. et al. The dark side of technology: an experimental investigation of the influence of customizability technology on online political selective exposure. Comput. Hum. Behav. 73, 181–190 (2017).

Jain, T., Hazra, J. & Cheng, T. C. E. Illegal content monitoring on social platforms. Prod. Oper. Manage. 29(8), 1837–1857 (2020).

Reuter, K. et al. Public concern about monitoring Twitter users and their conversations to recruit for clinical trials: survey study. J. Med. Internet. Res. 21(10), e15455. (2019).

Slechten, L., Courtois, C., Coenen, L. & Zaman, B. Adapting the selective exposure perspective to algorithmically governed platforms: the case of Google search. Commun. Res. 49(8), 1039–1065 (2022).

Ibdah, D., Lachtar, N., Raparthi, S. M. & Bacha, A. Why should I read the privacy policy, I just need the service: a study on attitudes and perceptions toward privacy policies. Ieee Access. 9, 166465–166487 (2021).

Lyu, T., Guo, Y. & Chen, H. Understanding the privacy protection disengagement behaviour of contactless digital service users: the roles of privacy fatigue and privacy literacy. Behav. Inf. Technol. 1–17 (2023).

Knobloch-Westerwick, S. & Westerwick, A. Algorithmic personalization of source cues in the filter bubble: self-esteem and self-construal impact information exposure. New. Media Soc. 25(8), 2095–2117 (2023).

Minson, J. A. & Dorison, C. A. Why is exposure to opposing views aversive? Reconciling three theoretical perspectives. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 47, 101435 (2022).

Camaj, L. From selective exposure to selective information processing: a motivated reasoning approach. Media Communication. 7(3), 8–11 (2019).

Metzger, M. J., Hartsell, E. H. & Flanagin, A. J. Cognitive dissonance or credibility? A comparison of two theoretical explanations for selective exposure to partisan news. Communication Res. 47(1), 3–28 (2020).

Wojcieszak, M. What predicts selective exposure online: testing political attitudes, credibility, and social Identity. Communication Res. 48(5), 687–716 (2021).

Zillich, A. F. & Guenther, L. Selective exposure to information on the internet: measuring cognitive dissonance and selective exposure with eye-tracking. Int. J. Communication. 15, 3459–3478 (2021).

Kruglanski, A. W. & Fishman, S. Psychological factors in terrorism and counterterrorism: individual, group, and organizational levels of analysis. Social Issues Policy Rev. 3(1), 1–44 (2009).

Shi, Z. & Zhang, S. Review and prospect of neuromarketing ERP research. J. Manage. World. 38(4), 226–240 (2020).

Wang, J., Lin, J. & Li, D. Exploration and application of cognitive mechanism of destination brand personality: taking an ERP experiment of college students as an exampl. Nankai Bus. Rev. 4, 206–218 (2018).

Fischer, P. et al. Neural mechanisms of selective exposure: an EEG study on the processing of decision-consistent and inconsistent information. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 87(1), 13–18 (2013).

Festinger, A. L. 194–198. (Stanford University Press, 1957).

Hart, W. et al. Feeling validated Versus being correct: a meta-analysis of selective exposure to information. Psychol. Bull. 135(4), 555–588 (2009).

Park, J., Konana, P., Gu, B., Kumar, A. & Raghunathan, R. Information valuation and confirmation bias in virtual communities: evidence from stock message boards. Inform. Syst. Res. 24(4), 1050–1067 (2013).

Legoux, R., Leger, P. M., Robert, J. & Boyer, M. Confirmation biases in the financial analysis of IT Investments. J. Association Inform. Syst. 15(1), 33–52 (2014).

Deng, S. & Zhao, H. The influence of personality on the selective information exposure pattern in biased information seeking processes. Inform. Sci. 37(3), 152–157 (2019).

Westerwick, A., Johnson, B. K. & Knobloch-Westerwick, S. Confirmation biases in selective exposure to political online information: source bias vs. content bias. Communication Monogr. 84(3), 343–364 (2017).

Yin, D., Mitra, S. & Zhang, H. When do consumers value positive vs. negative reviews? An empirical investigation of confirmation bias in online word of mouth. Inform. Syst. Res. 27(1), 131–144 (2016).

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., Mothes, C., Johnson, B. K., Westerwick, A. & Donsbach, W. Political online information searching in Germany and the United States: confirmation bias, source credibility, and attitude impacts. J. Communication. 65(3), 489–511 (2015).

Jonas, E., Schulz-Hardt, S., Frey, D. & Thelen, N. Confirmation bias in sequential information search after preliminary decisions: an expansion of dissonance theoretical research on selective exposure to information. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 80(4), 557–571. (2001).

Turcotte, J., York, C., Irving, J., Scholl, R. M. & Pingree, R. J. News recommendations from social media opinion leaders: effects on media trust and information seeking. J. Computer-Mediated Communication. 20(5), 520–535 (2015).

Nikolov, D., Lalmas, M., Flammini, A. & Menczer, F. Quantifying biases in online information exposure. J. Association Inform. Sci. Technol. 70(3), 218–229 (2019).

Dogruel, L. Too much information!? Examining the impact of different levels of transparency on consumers’ evaluations of targeted advertising. Communication Res. Rep. 36(5), 383–392 (2019).

Shin, D. D. Algorithms, Humans, and Interactions: How do Algorithms Interact with People? Designing Meaningful AI Experiences 1st edn https://doi.org/10.1201/b23083 (Routledge, 2023).

Shin, D. The effects of explainability and causability on perception, trust, and acceptance: implications for explainable AI. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 146, 102551 (2021).

Shin, D. Artificial Misinformation: Exploring Human-Algorithm Interaction Online https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-52569-8 (Springer Nature, 2024).

Zhang, Y., Wang, T. & Hsu, C. The effects of voluntary GDPR adoption and the readability of privacy statements on customers’ information disclosure intention and trust. J. Intellect. Capital. 21(2), 145–163 (2020).

Herm, L. V., Heinrich, K., Wanner, J. & Janiesch, C. Stop ordering machine learning algorithms by their explainability! A user-centered investigation of performance and explainability. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 69, 102538 (2023).

Kruglanski, A. W. Lay Epistemics and Human Knowledge: Cognitive and Motivational Bases (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Wang, Y., Ahmed, S. & Bee, A. W. T. Selective Avoidance as a Cognitive Response: Examining the Political use of Social Media and Surveillance Anxiety in Avoidance Behaviours1–15 (Behaviour & Information Technology, 2023).

Chen, C. H. & Wu, I. C. The interplay between cognitive and motivational variables in a supportive online learning system for secondary physical education. Comput. Educ. 58(1), 542–550 (2021).

Wedderhoff, O., Chasiotis, A. & Rosman, T. When freedom of choice leads to bias: how threat fosters selective exposure to health information. Front. Psychol. 13, 937699 (2022).

Perez-Osorio, J., Abubshait, A. & Wykowska, A. Irrelevant robot signals in a categorization task induce cognitive conflict in performance, eye trajectories, the n2 component of the EEG signal, and frontal theta oscillations. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 34(1), 108–126 (2021).

Swanson, B., Hosch, A. & Petersen, I. The association of N2 Erp amplitudes with harsh parenting and inhibitory control in early childhood. Psychophysiology 59, S136–S136 (2022).

Che, X., Xu, H. & Wang, K. Precision requirement of working memory representations influences attentional guidance. Acta Physiol. Sinica 7, 694–713 (2021).

Folstein, J. R. & Van Petten, C. Influence of cognitive control and mismatch on the N2 component of the ERP: a review. Psychophysiology. 45(1), 152–170 (2008).

Savine, A. C. & Braver, T. S. Motivated cognitive control: reward incentives modulate preparatory neural activity during task-switching (retraction of August, Pg 10294, 2010). J. Neurosci. 33(20), 8922–8922 (2013).

Rauchbauer, B., Lorenz, C., Lamm, C. & Pfabigan, D. M. Cognitive Interplay of self-other distinction and cognitive control mechanisms in a social automatic imitation task: An ERP study. Affect. Behav. Neurosci., 21, 639–655. (2021).

Mckay, C. C., Berg, B. & Woldorff, M. G. Neural cascade of conflict processing: not just time-on-task. Neuropsychologia. 96, 184–191 (2017).

Hsieh, S. S., Huang, C. J., Wu, C. T., Chang, Y. K. & Hung, T. M. Acute exercise facilitates the N450 inhibition marker and P3 attention marker during stroop test in young and older adults. J. Clin. Med. 7(11), 391 (2018).

Larson, M. J., Clayson, P. E. & Clawson, A. Making sense of all the conflict: a theoretical review and critique of conflict-related ERPs. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 93(3), 283–297 (2014).

Shilling, A. A. & Brown, C. M. Goal-driven resource redistribution: an adaptive response to social exclusion. Evolutionary Behav. Sci. 10(3), 149–167 (2016).

Li, H., Yang, J. & Jia, L. Attentional bias in individuals with different level of self-esteem. Acta Physiol. Sinica. 43(8), 907–916 (2011).

Itzchakov, G. & Van Harreveld, F. Feeling torn and fearing rue: attitude ambivalence and anticipated regret as antecedents of biased information seeking. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 75, 19–26 (2018).

Petty, R. E., Brinol, P. & Tormala, Z. L. Thought confidence as a determinant of persuasion: the self-validation hypothesis. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 82(5), 722–741 (2002).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39(2), 175–191 (2007).

Yang, Z. & Wu, J. The relationship between ego depletion and attention bias of altruistic information, self-interested information. Tech. Appl. 3, 156–163 (2020).

Van Strien, J. L. H., Kammerer, Y., Brand-Gruwel, S. & Boshuizen, H. P. A. How attitude strength biases information processing and evaluation on the web. Comput. Hum. Behav. 60, 245–252 (2016).

Sun, R. & Luo, Y. Research on consumer privacy paradox behavior from the perspective of self-perception theory: evidence from ERPs. Nankai Bus. Rev. 4, 153–162 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qiuhua Zhu: Methodology, Writing–original draft, Software, Writing – review & editing, Data analysis. Rui Sun: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing–review & editing, Funding acquisition. Dong Lv: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. RuXia Cheng: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration. Jiajia Zuo: Experimental design and implementation, Project administration. Shukun Qin: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Huaqiao University (M2023009 2023.4.19).

Written informed consent

All participants in the study received written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Q., Sun, R., Lv, D. et al. Research on cognitive neural mechanism of consumers convinced by intelligent recommendation platform eavesdropping. Sci Rep 14, 28108 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79281-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79281-7