Abstract

In healthy adults different language abilities—sentence processing versus emotional prosody—are supported by the left (LH) versus the right hemisphere (RH), respectively. However, after LH stroke in infancy, RH regions often support both abilities with normal outcomes. This finding raises an important question: How does the functional map of RH regions change to support both emotional prosody and also typically left-lateralized language functions after an early LH stroke? Does sentence processing simply become reflected into RH frontotemporal regions and overlap with emotional prosody processing? Or do these functions overlap less than would be expected with simple mirroring? In the current work we used task fMRI to examine precisely how sentence processing and emotional prosody processing are both organized in the intact RH of individuals who suffered a large LH perinatal arterial ischemic stroke (LHPS participants). We evaluated the activation of two fMRI tasks that probed auditory sentence processing and emotional prosody processing, comparing the overlap for these two functions in the RH of individuals with perinatal stroke with the symmetry of these functions in the LH and RH of their healthy siblings. We found less activation overlap in the RH of individuals with LH perinatal stroke than would be expected if both functions retained their typical spatial layout, suggesting that their spatial segregation may be an important feature of a functioning language system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Language is a uniquely human cognitive function with an unusual pattern of organization in that it is strongly lateralized to the left hemisphere (LH) in most adults1,2. When left perisylvian regions are irreversibly damaged by a stroke to the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) in adulthood, patients consistently suffer a chronic language impairment, or aphasia3. Even several years after LH regions are lost, the RH is extremely limited in its ability to recover certain ‘core’ language abilities that are typically left-lateralized (see4,5 for an assessment of relevant plasticity factors). For these reasons, numerous studies have asked whether LH lateralization is also requisite for successful language acquisition from the beginning of life.

The clearest evidence against this idea comes from individuals who suffered an arterial ischemic stroke around the time of birth, called a perinatal stroke (defined as a stroke occurring between 28 weeks’ gestation and 28 postnatal days), which impacts the left MCA in approximately two-thirds of cases6. Many individuals who suffer a perinatal stroke do not have additional neurological or cardiovascular conditions. They therefore can provide a relatively clean model for how the cortical mapping of language processing proceeds when crucial LH cortical regions are unavailable during early cognitive development. In the absence of seizures or other complicating factors, language abilities in this population generally develop to be in the normal range7,8,9,10 after some degree of delay during early childhood11,12. We have collected a comprehensive battery of language assessments in mature perinatal stroke participants, many years after their stroke, and they perform well in all of the language areas examined (word structure, basic sentence comprehension, and comprehension of simple and complex syntax)9.

Neuroimaging investigations by our group and others have shown that language processing in left hemisphere perinatal stroke participants (henceforth LHPS participants) becomes organized in RH regions13,14,15, and that these regions are precisely homotopic to typical LH language centers8,9,16,17,18,19,20,21. There is increasing evidence to support this outcome in individuals who experienced an arterial ischemic stroke during the perinatal window, which is our focus here (see9,15,22 for elaboration on outcomes in other related populations). We have also found that the spatial pattern of RH recruitment during auditory sentence processing in LHPS participants is more similar to the pattern observed in the typical dominant LH than the weak activation observed in the typical nondominant RH, even when equating the amount of activation20. These findings demonstrate that the plasticity mechanisms available in the infant brain are capable of supporting the development of a ‘typical LH-like’ language system in RH perisylvian regions when LH regions are unavailable from birth.

These findings raise an important question: What happens, then, to the typical functions of the right perisylvian cortex if the functional map of these regions has been modified to support language processing that normally occurs in the LH? In the typical bi-hemispheric brain, right perisylvian regions ordinarily process suprasegmental functions, such as vocal emotion (emotional prosody). When adults suffer a right MCA stroke, they commonly show an impairment in processing emotional prosody, or aprosodia23. In healthy adults, emotional prosody processing is lateralized to right perisylvian regions, whereas ‘core’ language functions such as sentence processing are lateralized to left perisylvian regions. A recent study by Seydell-Greenwald, et al. found that right perisylvian regions were robustly active when healthy young adults made decisions about the emotion conveyed by a speaker’s voice, and these regions were symmetrical to the left perisylvian regions that were robustly active when they made decisions about the semantic content of spoken sentences24.

Only a few studies have examined emotional prosody processing after perinatal stroke, but they have found that this ability develops to be normal, and equivalently so after a left or right MCA stroke12,25. We recently conducted a neuroimaging study on our sample of LHPS participants and their typically developing siblings in which they performed distinct fMRI tasks, one that probed auditory sentence processing and another that probed emotional prosody processing9. In accord with previous work on healthy adults, these tasks activated perisylvian cortices in opposite hemispheres in healthy siblings: sentence processing primarily activated left perisylvian areas, and emotional prosody processing primarily activated right perisylvian areas. In LHPS participants, however, the result was both expected and remarkable: these two cognitive functions both activated right perisylvian regions9. This suggests that after a LH perinatal stroke, the typical map of functions in right perisylvian regions is modified to successfully implement both a sentence processing system and an emotional prosody system.

In the current study we asked precisely how sentence processing and emotional prosody regions co-exist in the same hemisphere. In particular, we measured the extent to which sentence processing areas overlapped with—or did not overlap with—emotional prosody areas in the right perisylvian cortex of individual LHPS participants. We examined task activation in two ways, which each captured a different possible outcome of functional plasticity.

We first investigated whether the extent of cortical recruitment for sentence processing and emotional prosody processing was different from the healthy brain after a perinatal stroke. These two functions could develop to occupy the same hemisphere by claiming a smaller amount of space than we normally observe when these functions lateralize to opposite hemispheres. Alternatively, one function could occupy the typical amount of space and as a consequence the other function could be confined to a smaller space than is typical.

We then investigated whether sentence processing and emotional prosody occupied overlapping cortical areas in the intact hemisphere after a perinatal stroke. Because these two functions typically lateralize to opposite hemispheres, they may each require different properties of the LH and RH perisylvian cortex for processing their distinct functions. When only one set of perisylvian regions is available from birth, these two functions may still require different properties of this same set of regions, which can perhaps be supported by separate subregions. Alternatively, these two functions may organize in spatially overlapping areas of perisylvian cortex, which would suggest that the same tissue that supports emotional prosody processing can also support sentence processing. To assess these possibilities, we employed a ‘top voxel’ approach20,26,27, which allows us to compare the same number of the most active voxels between participants and between hemispheres to evaluate similarity in the spatial arrangements of activity.

We hypothesized that, in light of the computational differences between these processes, both processes would retain sizeable territory in the RH but they would be driven to segregate to somewhat separate regions within the right frontal and temporal areas of LHPS participants. Our findings have important implications for our understanding of how the cortical layouts for sentence processing and emotional prosody form during development.

Results

The present study included thirteen LHPS participants with large cortical lesions from arterial ischemic strokes to the left MCA (n = 12) or internal carotid artery (n = 1) with no additional cardiovascular disease, chronic epilepsy, or neurological disorder, and eleven healthy siblings from the same families and roughly age-matched to the LHPS participants recruited for the study (Table 1).

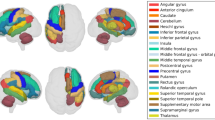

Participants completed two fMRI tasks (Fig. 1a). In the Auditory Description Decision Task (ADDT)28 participants heard blocks of short sentences containing descriptions of common nouns (Forward Speech condition) as well as blocks of unintelligible waveforms of the same descriptions played backwards (Reverse Speech condition). In the Emotional Prosody Decision Task (EPDT) participants made a three-alternative forced-choice about either the emotion (happy, sad, angry; Emotional Speech condition) or sentence content (traveling, eating, or gift-giving; Neutral Speech condition). We examined activation in the temporal and frontal lobes (Fig. 1b) to cast a reasonably wide net around the perisylvian regions engaged by our tasks. All participants performed the tasks with high accuracy, with no group differences in accuracy or response time (see Methods). Subsequent steps for the ‘top voxel approach’ and analysis of spatial similarity are visualized in Fig. 1c-d and described below.

Analysis overview. (a) For the Auditory Description Decision Task (ADDT; left), we left-right flipped the activation map for each control participant, and left the activation map for each left hemisphere perinatal stroke participant (LHPS). For the Emotional Prosody Decision Task (EPDT; right), we did not flip the activation maps for controls or LHPS participants. (b) We masked activation for both tasks in anatomical regions of interest and then (c) applied a top voxel cutoff to equalize the quantity of activation within each of these regions for all participants’ activation maps for both tasks. (d) Finally, we calculated the spatial overlap between the two activation maps (ADDT and EPDT) for each participant with a dice coefficient.

Extent of cortical recruitment for each function does not change when they must share the same hemisphere

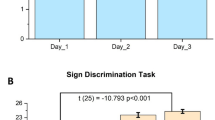

First, we compared groups on the extent of activation evoked by each task (Fig. 2a). If both functions share one hemisphere by each reducing the amount of cortex they recruit, the number of voxels with significant activation should be lower in the preserved hemisphere of perinatal stroke participants compared to controls. There was a significant main effect of task in the frontal lobe, reflecting greater activation for sentence processing than prosody within participants (F(1,22) = 0.008, p < 0.031), but no main effect of participant group and no interaction of participant group and task (Supplementary Table S1). This finding indicates that the extent of activation for sentence processing and emotional prosody was no different in our sample of perinatal stroke participants relative to healthy controls. Next, we examined a potential inverse relationship between the number of voxels activated by each task in the intact hemispheres of the LHPS participants. If both functions share one hemisphere by trading off the relative amount of space they occupy, more extensive activation for one task should be linearly related to less extensive activation for the other in perinatal stroke participants but not in controls. We found no evidence of such a relationship (Supplementary Fig.S1a).

Functions claim separate cortical territories when they must share the same hemisphere

We then asked, when the activation areas for the two tasks are equalized, do sentence processing and emotional prosody activations in the RH of LHPS participants overlap to the extent that would be expected if the typical LH activation for sentence processing were simply mirrored into the RH? We employed a ‘top voxel’ approach26,27 (Fig. 1c) which allows us to compare the same number of the most active voxels between participants and between hemispheres to evaluate similarity in the spatial arrangements of activity (measured using a Dice Coefficient; Fig. 1d). Importantly, this approach enforces that the areas we compare will be identical in size: this means that the voxels may differ in their absolute activation (as is common between different tasks and different participants), but if the most consistently active voxels (those with the highest t-values) for each task fall in the same spatial area, we can quantify that both tasks have a similar spatial distribution regardless of idiosyncrasies in activation magnitude.

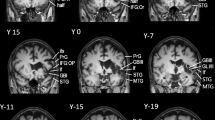

Task symmetry in controls was evaluated by comparing their RH prosody activations to their left-right flipped sentence processing activations, which serves as a proxy for how overlapping these activation maps could theoretically be if, after a LH perinatal stroke, typically left-lateralized language functions were simply transposed into the RH. Task overlap in LHPS participants was lower than task symmetry in controls in both the right frontal (t(17.7) = 2.49, p = 0.0229) and temporal lobes (t(16.6) = 4.77, p = 0.0002; Fig. 2b). These Dice Coefficients were measured at four top voxel levels and the average across levels was compared between participants. However, the same relationships persist at each level and using a conventional thresholding approach (Supplementary Fig. S2 & S3). Examples of the unique spatial layouts for these two tasks in LHPS participants illustrate that sentence processing and emotional prosody activate nearby but minimally overlapping areas, as compared with the task symmetry in the example controls (Fig. 3b). Group maps of task separation (Fig. 3a) reveal that in many LHPS participants emotional prosody claimed much of the mid-to-posterior superior temporal gyrus, while sentence processing claimed part of the posterior middle temporal gyrus (regions of task overlap and separation listed in Supplementary Table S2).

Activation extent and spatial overlap. (a) We compared the number of voxels with significant activation for each task and for each group. Individual participants are labeled with circles as well as their subject codes. Gray lines connect the data points for the different tasks for the same participant. Brackets are labeled with the p-values from two-tailed t-tests (paired within-group, independent samples between-groups). See Supplementary Fig. S2 for Spearman correlations on the number of active voxels for each task in LHPS participants and controls. (b) The Dice Coefficient averages are shown for individual participants (circles and subject codes) within each group: in blue, the symmetry of task activations in individual controls; in green, the overlap of task activations in individual LHPS participants. Brackets are labeled with the p-values from independent samples t-tests. See Supplementary Fig. S3 for the Dice Coefficient relationships at each individual top voxel level and Supplementary Fig. S4 for the Dice Coefficient relationships using a conventional thresholding approach.

Individual participant maps and group penetrance maps of activation overlap and separation. (a) In the task overlap penetrance maps (top row), yellow areas reflect regions with greater consistency (a greater number of participants) in task overlap or symmetry across the group. In the task separation maps (bottom row), brighter blue areas reflect greater consistency for sentence-processing-only top voxels, while brighter red areas reflect greater consistency for prosody-only top voxels. Brain areas exhibiting consistent overlap or separation are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. (b) Axial and sagittal slices of the top voxel maps for each task and their overlap (in green) are overlaid onto the MNI template for three control participants (top row) and three LHPS participants (bottom row). There was significantly less overlap between tasks in the RH of LHPS participants than was measured in controls (quantified in Fig. 2). (c) Lesion overlap in the LH is depicted for the stroke participants.

Given the relatively large age range of our participants (10 to 29.5 years old) and the fact that frontal and temporal regions are known to play quite different roles in language processing, we conducted additional ANOVAs including age as a covariate and modeling both ROIs together to explore potential effects of age and group by region interactions for both activation extent (Supplementary Table S3) and spatial overlap (Supplementary Table S4 & Fig. S4). Age had no significant effect on activation extent or spatial overlap in either task, and including age as a covariate did not impact the group differences in spatial overlap (which remained significant at p < 0.001) or the lack of observed differences in activation extent. Modelling both ROIs together revealed a region-by-participant group interaction for spatial overlap (F(1,21) = 4.91, p = 0.038), reflecting that the difference between groups was especially pronounced in the temporal ROI relative to the frontal ROI.

Discussion

In the present work we examined how two processes that lateralize to homotopic regions of different hemispheres in the typical brain (sentence processing and emotional prosody processing) are organized in the one intact hemisphere of individuals who suffered a large LH stroke around the time of birth. We found that these two functions do not activate any less territory when they both lateralize to one hemisphere relative to healthy controls. There was also no evidence that one function activates a smaller area while the other activates a larger area in the RH of perinatal stroke participants. Despite the extent of activation for both tasks being approximately the same in LHPS participants as in healthy controls, we did not find a high degree of overlap between the activated areas in the RH of LHPS participants. Thus, rather than developing a RH sentence processing system that is entirely superimposed onto the typical RH emotional prosody regions, sentence processing and emotional prosody processing appear to claim somewhat separate cortical territories in right perisylvian cortex after a left hemisphere perinatal stroke.

As a caveat, it is possible that our fMRI task design and analysis may influence the degree of overlap in activation that we are measuring. In particular, our emotional prosody contrast (Emotional > Neutral Speech) will lead us to eliminate from attention those areas that are active during both emotional prosody and sentence processing. Here we focus on whether there is overlap in the areas that preferentially process emotional prosody and the areas that preferentially process sentences. While there are undoubtedly also areas that are active during both tasks, the areas that preferentially process each type of information consistently segregated in the RH of our sample of LHPS participants.

While our sample size is small relative to modern neuroimaging studies of healthy adults, it is substantial for a homogeneous cohort of people with perinatal arterial stroke. Notably, and unlike other studies of perinatal injury, we include only large cortical strokes, and we do not include periventricular venous infarcts. Participants were all assessed at an age when recovery and language development is likely complete29. Moreover, age at time of testing and location of strokes did not impact our results. Individual stroke participants—despite their differences in age at testing and specific lesion location—exhibited a robust pattern of functional separation between sentence processing and emotional prosody processing areas, which was significantly different from the pattern of consistent spatial overlap observed in controls.

Regional effects

We observed that in both the frontal and temporal lobes, stroke participants exhibited reduced spatial overlap in their task activations relative to healthy controls. In the temporal lobe this difference was more pronounced. Within each group, there was no difference in the degree of overlap (or non-overlap) in the frontal and temporal ROIs. However, individual controls tended to have slightly greater overlap in temporal than frontal regions, and individual LHPS participants tended to have slightly less overlap in temporal than frontal regions. This divergence was sufficient to produce a significant interaction effect, whereby spatial overlap was especially low in temporal regions in LHPS participants. Activation in the frontal and temporal lobes varies between tasks and between individuals, so this augmented separation in the temporal lobe may relate more to experimental design than variation in neurobiology. However, it is also plausible that frontal and temporal cortex differ regarding their maturational timelines and/or capacity for plasticity early in life. Few studies have examined structural connections in the right-lateralized language system after perinatal stroke15,30. More information is needed to ascertain whether there are more pronounced structural differences in certain areas and/or pathways of the preserved right hemisphere that might explain why functional separation is more pronounced in the temporal lobe.

We also observed regional differences within the frontal and temporal lobes that suggest a potentially interesting pattern in dorsal stream plasticity, which has been observed in prior studies as well. In the current study, a few regions were consistently more active for sentence processing than emotional prosody in the RH of LHPS participants that did not show a task preference in controls. These regions—posterior MTG, more dorsal parts of IFG, and the anterior insula—are part of the dorsal stream for speech processing and are connected by the long segment of the arcuate fasciculus. Prior studies in various developmental populations have identified plasticity differences between the dorsal versus ventral streams31,32,33,34,35,36,37, and maturation of specific dorsal stream tracts is associated with early language experience38. Here we have found that certain dorsal stream regions in the RH may have undergone plastic change to serve as subregions for sentence processing in LHPS participants, which may reflect the plastic potential of the dorsal stream. These findings again highlight the need for a rigorous examination of the structural connections in the preserved right perisylvian cortex after perinatal stroke, and how maturational timelines for different tracts might explain the patterns of functional organization that we and others have observed.

Crowding effects

Our findings raise the question of whether there are any ‘crowding effects’ once sentence processing organizes atypically in the right hemisphere. Unfortunately, we cannot interpret crowding effects in the present study. The crowding hypothesis refers to a reduction of neural resources in the right hemisphere for the functions ordinarily subserved by that hemisphere (most commonly regarding visuospatial functions) when language organizes after early injury39. Crowding has been examined in pediatric epilepsy and tissue resection40,41, but Lidzba and colleagues have performed the only studies investigating crowding after perinatal stroke. In a mixed sample of pre- and perinatal venous and arterial strokes, they found reduced visuospatial processing and nonverbal auditory memory abilities in stroke participants with RH language42,43. Here we focused on the cortical mapping of sentence processing and emotional prosody processing using simple tasks that did not probe the boundaries of performance. The few studies that have probed emotional prosody processing proficiency in this population found that emotional prosody was normal after injury to either hemisphere10,12,25. One potentially important difference between visuospatial and emotional prosody processing that might produce a difference in their susceptibility to crowding is that the ability to process emotional prosody develops very early, as does ‘core’ language processing, whereas visuospatial functions develop later in childhood. A future study should probe more demanding emotional prosody judgments in individuals with right-lateralized language after LH perinatal stroke to examine potential crowding effects.

What leads to task segregation?

When sentence processing and emotional prosody processing develop in the healthy brain, they lateralize to perisylvian cortex in opposite hemispheres. One explanation for this opposite lateralization is that these functions each require computational properties that are found in the left and right perisylvian cortex, respectively. There is increasing evidence that the LH and RH auditory systems have preferences for temporally-rich versus spectrally-rich acoustic information, and that this lateralization in early-level processing may push ‘core’ language processing to the left and ‘suprasegmental’ auditory processing (such as emotional prosody) to the right hemisphere44,45,46,47. The acoustic features that carry information about prosody unfold over a more prolonged timescale than the features that carry segmental and syntactic information45,48, reflected in the temporal signatures of the neural processing for these elements of the speech signal49. Wiethoff et al. (2008) found correlations between the acoustic features of voice information (intensity, duration, and fundamental frequency mean and variation) and the heightened neural response to words spoken with emotional vs. neutral intonation in the right mid-STG50. In addition, another study showed that temporary TMS inhibition of the right STG (but not the left) impaired emotional content judgments by participants51.

After an arterial perinatal stroke, only one set of perisylvian regions is available to support both sentence processing and emotional prosody processing. Given the different computational requirements for these functions, the right perisylvian cortex may develop subregions that preferentially process each function separately. This is indeed what our results suggest.

How might this functional separation develop? For separate subregions to form to support sentence processing and emotional prosody, the functional development of these two processes would need to be interactive—perhaps even competitive. Theories of ‘competitive specialization’52,53 describe how neural systems that have slight differences in their structure can become functionally tailored for processing different dimensions of incoming information from the environment. For example, ‘mixture-of-experts’ models54,55 have demonstrated how systems might develop to process categorical (e.g., “this is above”) versus coordinate information (e.g., “this is 3 cm above”) or to process what (e.g., “a chair”) versus where (e.g., “over there”) information about visual inputs53,56. In this framework, computationally different subnetworks (‘experts’) are all exposed to the input data for complex tasks; over trials, the likelihood that a given expert will be boosted for a specific task is increased if its error is less than average for that task55. Through several iterations, one expert becomes increasingly specialized for one type of task (e.g., judging ‘what’) while the other expert becomes specialized for a different task (e.g., judging ‘where’).

A similar process may give rise to specialized systems for sentence processing and emotional prosody, either in separate hemispheres of the healthy brain or in subregions of the one intact hemisphere after perinatal stroke. Initially (that is, early in life), subregions may differ in their ability to process different types of input (e.g. lexicosemantic features versus emotion). This may be due to small neuronal populations being biased toward shorter versus longer temporal integration windows. Neuronal populations of both kinds (short vs. long temporal integration; temporal vs. spectral selectivity) are thought to exist in both hemispheres of the typical brain; there is simply a greater number of one kind that creates an overall bias for more efficient processing of one type of input in each hemisphere45. Thus both types of neuronal populations should exist in the right perisylvian cortex of all individuals and would be available for enhancement in those with LH perinatal stroke. Over time, this process may result in two separate specialized systems, one for sentence processing and another for emotional prosody processing.

Conclusion

After a stroke at birth irreversibly damages left hemisphere language regions, parallel right hemisphere regions often adopt typical left hemisphere language functions. How does this alternative organization of language functions impact the typical mapping of right hemisphere functions? Here we rejected the hypothesis that sentence processing is essentially mirrored into the right hemisphere and recruits precisely the same frontal and temporal areas that process emotional prosody. Instead, we identified consistent separation between activation areas (i.e., subregions) for sentence processing and emotional prosody processing in the preserved right perisylvian cortex of perinatal stroke participants. When development proceeds after these early life injuries, right hemisphere regions may undergo plastic changes that allow them to support typical functions and also adopt atypical functions. Our results suggest this outcome is in part implemented through functional partitioning via subregions in right frontal and temporal cortex.

Methods

Participants

The data for the current study were collected as part of the Pediatric Stroke Research Project at Georgetown University8,9. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Georgetown University Medical Center. All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations; all participants provided informed consent (adults) or parental informed consent and child assent (children). For the present analyses, thirteen perinatal arterial ischemic stroke participants (six female) were included, all of whom suffered a large cortical stroke to the left middle cerebral artery (the left internal carotid for one participant) with no additional diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, chronic epilepsy, or neurological disorder other than perinatal stroke. Diagnostic imaging was performed in the first 5 days of life for 3 participants and after the perinatal period for 10 participants. The proportion of the LH that was lesioned in this sample of LHPS participants ranged from 0.18 to 0.99, with an average of 0.49. Eleven healthy controls (three female) were also included, who are siblings from the same families and roughly age-matched to the stroke participants recruited for the study. Three control participants are the siblings of these left hemisphere perinatal stroke participants; two are younger siblings (by approximately 2 years and approximately 6.5 years) and one is an older sibling (by approximately 2.5 years). Eight control participants are the siblings of individuals with an early life stroke of other types who are therefore not included in this study (1 LH stroke who did not get scanned, 5 right hemisphere strokes, two subcortical strokes). None of the other control participants or perinatal stroke participants are related to one another. We did not include three additional participants that were included in prior analyses:9 one stroke participant and one healthy control were too young (we applied an age cutoff of 10 years old for the current study to ensure that sentence processing was fully lateralized29, and one stroke participant’s prosody scan data was unavailable at the time of this analysis. See Newport et al., 2022 for more detailed information about participant inclusion and language outcomes9. Supplementary Table S5 contains participant codes for comparison between this and previously published papers on the same participants.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Auditory description decision task (ADDT)

The Auditory Description Decision Task (ADDT) is a sentence processing task developed by Gaillard and colleagues28,29,57 and was modified for use in the Pediatric Stroke Research Project8,9. Briefly, participants heard blocks of short sentences containing auditory descriptions of common nouns (e.g., A large gray animal is an elephant) and were instructed to press a button if the description was correct (Forward Speech condition). They also heard blocks of unintelligible waveforms of the same descriptions played backwards and were instructed to press a button when a tone followed the auditory sequence (Reverse Speech condition). Each run (5:48 in duration) contained alternating blocks of Forward and Reverse Speech conditions (30 s each), beginning with Reverse Speech, with 12-second silent periods interspersed between blocks. Button presses were prompted on 50% of Forward Speech stimuli and 50% of Reverse Speech stimuli. Stimuli in each block were presented every 5 s, with a 3-second stimulation period followed by a 2-second response window. Runs were re-collected if motion was excessive, and two runs were analyzed for each participant. For the Forward Speech condition, controls had a mean accuracy of 97.5% +/- 2.4% (93.8–100.0%) (reported as mean +/- standard deviation, in parentheses range) and LHPS participants had a mean accuracy of 95.2% +/- 6.1% (79.2–100.0%). For the Reverse speech condition, controls had a mean accuracy of 99.2% +/- 1.4% (95.8–100.0%) and LHPS participants had a mean accuracy of 97.9% +/- 2.1% (93.8–100.0%). Independent samples t-tests did not reveal differences between participant groups in the response times for the Forward or Reverse conditions.

Emotional prosody decision Task (EPDT)

The emotional prosody decision task (EPDT) was designed by Seydell-Greenwald and colleagues24 to be similar in structure to the ADDT but with alternating Emotional Speech and Neutral Speech conditions. During the Emotional Speech condition, participants heard short sentences spoken in one of three emotions (happy, sad, or angry) which were each followed by one of three visual cues (sun, raindrop, or boxing glove). During the Neutral Speech condition, participants heard short sentences whose semantic content was about one of three activities (traveling, eating, or gift giving) spoken in a neutral tone. These sentences were followed by a visual cue representing one of the three activities (car, plate and utensils, gift box). Participants were instructed to press a button when the visual cue matched the speaker’s emotion (50% of Emotional Speech sentences) or the speaker’s activity (50% of Neutral Speech sentences). All participants completed two runs of the task. Each run (5:00 duration) contained eight 24-second blocks beginning with three seconds of written instructions and comprised of 6 sentences (each roughly 2 s in duration, followed by a 2 s response period). Silent periods (12 s long) were interspersed between blocks. Runs were repeated if motion was excessive, and two runs were analyzed for each participant. For the Emotional Speech condition, controls had a mean accuracy of 92.6% +/- 6.7% (81.3–100.0%) and LHPS participants had a mean of 92.3% +/- 7.0% (77.1–100.0%). For the Neutral Speech condition, controls had a mean of 96.8% +/- 2.5% (91.7–100.0%) and LHPS participants had a mean of 91.3% +/- 6.7% (79.2–100.0%). Independent samples t-tests did not reveal differences between participant groups in the response times for the Emotional or Neutral conditions.

Scanner and auditory equipment

Participants were scanned on a 3 Tesla Siemens MAGNETOM Trio scanner using a 12-channel headcoil at Georgetown University’s Center for Functional and Molecular Imaging. Three participants were scanned after a scanner upgrade to a Prisma model with a 20-channel head coil. Auditory stimuli for both tasks were delivered through Sensimetrics Model S14 insert headphones. Participants were also fitted with additional Bilsom ear defenders to reduce scanner noise, and they confirmed that they could clearly hear the task stimuli.

Scan sequences

A high-resolution anatomical image was collected and was repeated if motion was excessive: Siemens MPRAGE, 176 sagittal slices, TR = 2.53s, TE = 3.5ms, flip angle = 7 deg, 1 × 1 × 1 mm voxels, whole brain coverage. While participants completed the ADDT, 116 whole brain volumes were collected for each of the two functional runs: functional echo-planar images, 50 horizontal slices, descending order, TR = 3s, TE = 30ms, flip angle = 90 deg, 3 × 3 × 3 mm voxels. One of the control participants completed an earlier version of the task, which included 120 whole brain volumes. The 100 whole brain volumes collected for each of the two runs of the EPDT had the same acquisition parameters as the ADDT.

fMRI processing

The MRI scans in the current study were processed using SPM-12 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at University College London, https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/doc/). Preprocessing included slice-timing correction, realignment to the middle volume of each run, co-registration to the native-space anatomical image, spatial normalization to the MNI-152 average template (resulting resolution 2 mm), and then smoothing (8 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel). The fMRI time-courses for voxels inside the brain were statistically modeled using a general linear model that included the two conditions of interest (Forward and Reverse Speech, or Emotional and Neutral Speech) which were convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function, as well as motion estimates for rotation and translation along the x-, y-, and z-axes, and a high-pass filter for the duration of the task run. For each task, we then calculated voxel-wise t-tests on the beta maps for the conditions of interest to generate statistical contrast maps for Forward > Reverse Speech (sentence processing) activity and Emotional > Neutral Speech (emotional prosody) activity (Fig. 1a). Deactivations were excluded by thresholding the statistical maps to only include non-negative voxels.

Regions of interest (ROIs)

The frontal and temporal lobe anatomical masks from the WFU-Pick Atlas58 were resliced to match the dimensions of the MNI-space anatomical and statistical maps and were used to isolate frontal and temporal activations (Fig. 1b).

Activation analyses

Extent of activation

We first asked whether the activation extent was lower for sentence processing or emotional prosody processing when both functions were lateralized to the same hemisphere compared to their typical bi-hemispheric distribution (Fig. 2a). We thresholded every participant’s statistical map for each task (voxelwise p < 0.001 with minimal clustering, k≥4) and counted the number of active voxels in the frontal and temporal ROIs. For controls, we counted the active voxels in the LH for sentence processing and in the RH for emotional prosody processing. For LHPS participants, we counted the active voxels for each task in the RH. By comparing the number of active voxels in controls to LHPS participants for each task, we can determine whether the extent of cortical recruitment for sentence processing or emotional prosody processing may be different after a perinatal stroke. We also examined the relationship in the amount of activation for both tasks among LHPS participants to determine whether there was an inverse relationship. If so, it would suggest that across LHPS participants, one function activated a smaller area when the other activated a larger area within RH perisylvian cortex.

Spatial overlap

We also measured the degree to which the activations for these two tasks overlapped within each person, following a procedure we have used in prior studies to examine activation symmetry and spatial similarity between individuals20,27. The question motivating this analysis was whether the amount of overlap in the RH of LHPS participants would be less than the amount of overlap observed when sentence processing was transposed into the RH of controls—in other words, if sentence processing was simply mirrored into the LH after an early life stroke. This analysis involved three steps: first, we left-right flipped controls’ ADDT (sentence processing) activation maps (Fig. 1A), then we used a top voxel approach to identify the same number of most active voxels for each task and for each person (Fig. 1C) in two anatomical ROIs (one frontal, one temporal, see Fig. 1B), and finally, we quantified the overlap between these equal-size maps for each person using a Dice Coefficient (Fig. 1D). These steps, described in detail below, were performed at multiple activation thresholds so that our comparisons were not biased by arbitrary threshold selection (e.g., Fig. 2B, Dice Coefficient “Mean Across Levels”).

Flipped ADDT activation maps for controls

Part of our current investigation involved quantifying the degree of symmetry or expected overlap between the LH activation for sentence processing and the RH activation for emotional prosody processing in the healthy brain. To calculate this symmetry or expected overlap, we flipped each control’s structural and functional images across the midline (using SPM-12’s reorient utility) before preprocessing (Fig. 1a). Their flipped LH activity was then co-registered to their flipped LH anatomy. Then, in order to address structural asymmetries between the two hemispheres59, we spatially normalized the flipped images to the MNI template anatomy such that the participant’s flipped LH activation was warped to the template’s RH anatomy. To summarize, in this step we transposed the LH sentence processing activation into the RH for each control so that we could measure left-right symmetry for sentence processing (LH) and emotional prosody processing (RH).

Top voxel approach

Before measuring overlap between the activation maps for both tasks, we first applied a data-driven approach for selecting the same number of the most active voxels for both tasks. The purpose of this step was to generate equal-sized activation maps to be spatially compared for every person. Equalizing the size of the maps being spatially compared simplifies the interpretation of activation overlap/non-overlap. When the two maps are the same size for every person, the amount of overlap for each person (i.e., the Dice Coefficient, which is described in the next section) is a straightforward percentage that reflects the size of the intersecting area for both maps, and is directly comparable between people.

First, we applied four different statistical thresholds (p < 0.01, p < 0.005, 0 < 0.001, p < 0.0005) with minimal clustering (k≥4) to every participant’s ADDT (Forward > Reverse Speech) and EPDT (Emotional > Neutral Speech) statistical map. Within each ROI, we found the number of voxels that survived at each threshold for each task. For controls, we counted the active voxels in the LH for the ADDT and in the RH for the EPDT. In LHPS participants, we counted the active voxels for each task in the RH. We averaged this voxel count for both tasks across all participants at each of the four thresholds, which produced four top voxel cutoffs (Fig. 1c). For each participant, we then ranked the t-values in the ROI from highest to lowest and generated a new constrained map that included the top N voxels in each ROI for each task. We use N here because the number of voxels changes depending on the cutoff and the ROI: for instance, in the frontal ROI for the p < 0.01 threshold, the top N voxels for both tasks would be 2,216 voxels, because that was the average number of voxels active across all participants for both tasks in the frontal ROI at that p-threshold. We repeated this for each top voxel cutoff. As a result of this procedure, for each of the four cutoffs, every participant had a set of size-matched ADDT and EPDT maps in the frontal and temporal lobe (Fig. 1d). We also analyzed the spatial overlap using a conventional thresholding approach at four p-thresholds for comparison (Supplementary Fig.S3).

Dice Coefficient

We measured spatial overlap between the two tasks’ activation maps by calculating a Dice Coefficient for each participant, which is a ratio of the number of overlapping voxels for the two activation maps (x and y) relative to the total number of active voxels in both maps (Fig. 1d):

We calculated a Dice Coefficient for each ROI separately at each top voxel cutoff. We then averaged these Dice Coefficients calculated across all four cutoffs to obtain one summary value of spatial overlap within each region for each participant that was reasonably unbiased. For control participants, we measured the spatial overlap between their flipped LH ADDT map and their unflipped RH EPDT map to quantify how symmetrical the task activations were in each person. For LHPS participants, we measured the spatial overlap between their RH ADDT and EPDT maps to quantify how overlapping the activation areas were in each person’s intact hemisphere (Fig. 2b).

Penetrance maps

Penetrance maps (Fig. 3) visualize where spatial overlap was most consistent across participants in each group. We created task overlap penetrance maps and task separation penetrance maps, which show the brain areas that were most commonly active for both tasks or most commonly active for one task but not the other, respectively. At each voxel of the task overlap penetrance maps, there is a percentage value reflecting the number of participants who had task overlap at that voxel. At each voxel of the task separation maps, there is a percentage value reflecting the number of participants who had activation for one task but not the other (activation meaning it was one of the top voxels for one task but not the other) at that voxel. These maps were rendered on the MNI-152 standard template using MRIcroGL (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricrogl). The same approach used to generate the task overlap penetrance maps was also used to generate the lesion density map in Fig. 3C. We merged each LHPS participant’s binarized lesion tracing in MNI space, so that at each voxel there is a percentage reflecting the number of participants who have a lesion at that voxel.

Statistical comparisons

Statistical analyses were performed using R through R-Studio (http://www.R-project.org/) and the JASP toolbox open-source statistical software (version 0.14.1; https://jasp-stats.org/download/). For our analysis of activation extent, we performed two types of statistical tests. First, we calculated two-way repeated measures ANOVAs to measure the effect of task (ADDT or EPDT, within-subject) and group (LHPS or Control, between-subjects) as well as the interaction between task and group on the amount of activation measured (Fig. 1a in the main text). Second, we calculated Spearman correlations on the extent of activation for the ADDT and the EPDT across LHPS participants to determine whether a larger area recruited by sentence processing correlated with a smaller area recruited by emotional prosody processing (or the reverse). We also performed Spearman correlations on the extent of activation in each hemisphere for control participants. These correlations are included in Supplementary Fig.S1. For our analysis of spatial overlap, using the top voxel-constrained maps, we calculated two-tailed independent samples t-tests in the frontal and temporal ROIs to compare the Dice Coefficients measuring task overlap in LHPS participants to the Dice Coefficients measuring task symmetry in controls (Fig. 2b in the main text). This allowed us to evaluate whether the overlap for these tasks in the RH of LHPS participants was less than would be expected if sentence processing was physically transposed into the RH in the healthy brain. See Supplementary Tables S3&S4 for ANOVAS including age as a covariate, and modeling the ROIs together.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Broca, P. Remarks on the seat of the faculty of articulated language, following an observation of aphemia (loss of speech). Bull. Soc. Anat. 6, 330–357 (1861).

Knecht, S. et al. Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain 123, 2512–2518 (2000).

Alexander, M. P. Aphasia I: Clinical and anatomic issues. In Patientbased Approaches to Cognitive Neuroscience 165–181 (2000).

Turkeltaub, P. E. A taxonomy of brain-behavior relationships after stroke. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 62, 3907–3922 (2019).

Plowman, E., Hentz, B. & Ellis, C. Post-stroke aphasia prognosis: A review of patient-related and stroke-related factors. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 18, 689–694 (2012).

Ferriero, D. M. et al. Management of stroke in neonates and children: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association/American stroke association. Stroke https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000183 (2019).

Fair, D. A. et al. The functional organization of trial-related activity in lexical processing after early left hemispheric brain lesions: An event-related fMRI study. Brain Lang. 114, 135–146 (2010).

Newport, E. L. et al. Revisiting Lenneberg’s hypotheses about early developmental plasticity: Language organization after left-hemisphere perinatal stroke. Biolinguistics 11, 407–422 (2017).

Newport, E. L. et al. Language and developmental plasticity after perinatal stroke. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2207293119 (2022).

Stiles, J., Reilly, J. S., Levine, S. C., Trauner, D. A. & Nass, R. In Neural Plasticity and Cognitive Development: Insights from Children with Perinatal Brain Injury. (2012).

Bates, E. Plasticity, localization, and language development. In Biology and Knowledge Revisited 223–272 (Routledge, 2014).

Trauner, D. A., Eshagh, K., Ballantyne, A. O. & Bates, E. Early language development after peri-natal stroke. Brain Lang. 127, 399–403 (2013).

Ilves, P. et al. Different plasticity patterns of language function in children with perinatal and childhood stroke. J. Child Neurol. 29, 756–764 (2014).

François, C. et al. Right structural and functional reorganization in four-year-old children with perinatal arterial ischemic stroke predict language production. eNeuro 6, (2019).

François, C., Garcia-Alix, A., Bosch, L. & Rodriguez-Fornells, A. Signatures of brain plasticity supporting language recovery after perinatal arterial ischemic stroke. Brain Lang. 212, 104880 (2021).

Guzzetta, A. et al. Language organisation in left perinatal stroke. Neuropediatrics 39, 157–163 (2008).

Martin, K. C., Ketchabaw, W. T. & Turkeltaub, P. E. Plasticity of the language system in children and adults. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 184, 397–414 (2022).

Staudt, M. et al. Right-hemispheric organization of language following early left-sided brain lesions: Functional MRI topography. NeuroImage 16, 954–967 (2002).

Tillema, J. M. et al. Reprint of ‘Cortical reorganization of language functioning following perinatal left MCA stroke’ [Brain and Language 105 (2008) 99–111]. Brain Lang. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2008.08.001 (2008).

Martin, K. C. et al. One right can make a left: Sentence processing in the right hemisphere after perinatal stroke. Cereb. Cortex bhad362 (2023).

Jacola, L. M. et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging reveals atypical language organization in children following perinatal left middle cerebral artery stroke. Neuropediatrics 37, 46–52 (2006).

Lidzba, K., de Haan, B., Wilke, M., Krägeloh-Mann, I. & Staudt, M. Lesion characteristics driving right-hemispheric language reorganization in congenital left-hemispheric brain damage. Brain Lang. 173, 1–9 (2017).

Ross, E. D. The aprosodias: Functional-anatomic organization of the affective components of language in the right hemisphere. Arch. Neurol. 38, 561–569 (1981).

Seydell-Greenwald, A., Chambers, C. E., Ferrara, K. & Newport, E. L. What you say versus how you say it: Comparing sentence comprehension and emotional prosody processing using fMRI. NeuroImage 209, 116509 (2020).

Ballantyne, A. O., Spilkin, A. M. & Trauner, D. A. Language outcome after perinatal stroke: Does side matter?. Child Neuropsychol. 13, 494–509 (2007).

Wilson, S. M., Bautista, A. & McCarron, A. Convergence of spoken and written language processing in the superior temporal sulcus. Neuroimage 171, 62–74 (2018).

Martin, K. C. et al. A weak shadow of early life language processing persists in the right hemisphere of the mature brain. Neurobiol. Lang. 1–49 (2022).

Gaillard, W. D. et al. Atypical language in lesional and nonlesional complex partial epilepsy. Neurology 69, 1761–1771 (2007).

Berl, M. M. et al. Regional differences in the developmental trajectory of lateralization of the language network. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 270–284 (2014).

Marcelle, M. Structural language connectivity in typical development and after early brain injury. (2024).

Brauer, J., Anwander, A., Perani, D. & Friederici, A. D. Dorsal and ventral pathways in language development. Brain Lang. 127, 289–295 (2013).

Catani, M. & Bambini, V. A model for social communication and language evolution and development (SCALED). Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 28, 165–171 (2014).

Loenneker, T. et al. Microstructural development: Organizational differences of the fiber architecture between children and adults in dorsal and ventral visual streams. Hum. Brain Mapp. 32, 935–946 (2011).

Ayzenberg, V., Granovetter, M. C., Robert, S., Patterson, C. & Behrmann, M. Differential functional reorganization of ventral and dorsal visual pathways following childhood hemispherectomy. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 64, 101323 (2023).

Cheng, Q., Roth, A., Halgren, E. & Mayberry, R. I. Effects of early language deprivation on brain connectivity: Language pathways in deaf native and late first-language learners of American Sign Language. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 320 (2019).

Ferjan Ramirez, N. et al. Neural language processing in adolescent first-language learners: Longitudinal case studies in American Sign Language. Cereb. Cortex 26, 1015–1026 (2016).

Mitchell, T. V. & Neville, H. J. Asynchronies in the development of electrophysiological responses to motion and color. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 16, 1363–1374 (2004).

Huber, E., Corrigan, N. M., Yarnykh, V. L., Ramírez, N. F. & Kuhl, P. K. Language experience during infancy predicts white matter myelination at age 2 years. J. Neurosci. 43, 1590–1599 (2023).

Teuber, H.-L. Why two brains? In The Neurosciences: Third Study Program vol. F.O. Schmitt and F.G. Worden (Eds.) 71–74 (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1974).

Loring, D. W. et al. Effects of anomalous language representation on neuropsychological performance in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology 53, 260–260 (1999).

Danguecan, A. N. & Smith, M. L. Re-examining the crowding hypothesis in pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 94, 281–287 (2019).

Lidzba, K., Staudt, M., Wilke, M. & Krägeloh-Mann, I. Visuospatial deficits in patients with early left-hemispheric lesions and functional reorganization of language: Consequence of lesion or reorganization?. Neuropsychologia 44, 1088–1094 (2006).

Lidzba, K., Staudt, M., Wilke, M., Grodd, W. & Krägeloh-Mann, I. Lesion-induced right-hemispheric language and organization of nonverbal functions. Neuroreport 17, 929–933 (2006).

Albouy, P., Benjamin, L., Morillon, B. & Zatorre, R. J. Distinct sensitivity to spectrotemporal modulation supports brain asymmetry for speech and melody. Science 367, 1043–1047 (2020).

Poeppel, D. The analysis of speech in different temporal integration windows: cerebral lateralization as ‘asymmetric sampling in time’. Speech Commun. 41, 245–255 (2003).

Zatorre, R., Evans, A., Meyer, E. & Gjedde, A. Lateralization of phonetic and pitch discrimination in speech processing. Science 256, 846 (1992).

Zatorre, R. J. & Belin, P. Spectral and temporal processing in human auditory cortex. Cerebral Cortex 11, 946–953 (2001).

Rosen, S. Temporal information in speech: Acoustic, auditory and linguistic aspects. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B: Biol. Sci. 336, 367–373 (1992).

Eckstein, K. & Friederici, A. D. It’s early: Event-related potential evidence for initial interaction of syntax and prosody in speech comprehension. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 18, 1696–1711 (2006).

Wiethoff, S. et al. Cerebral processing of emotional prosody—Influence of acoustic parameters and arousal. Neuroimage 39, 885–893 (2008).

Alba-Ferrara, L., Ellison, A. & Mitchell, R. Decoding emotional prosody: Resolving differences in functional neuroanatomy from fMRI and lesion studies using TMS. Brain Stimul. 5, 347–353 (2012).

Jacobs, R. A. Computational studies of the development of functionally specialized neural modules. Trends Cogn. Sci. 3, 31–38 (1999).

Kosslyn, S. M. Seeing and imagining in the cerebral hemispheres: A computational approach. Psychol. Rev. 94, 148 (1987).

Jacobs, R. A. Bias/variance analyses of mixtures-of-experts architectures. Neural Comput. 9, 369–383 (1997).

Jacobs, R. A., Jordan, M. I., Nowlan, S. J. & Hinton, G. E. Adaptive mixtures of local experts. Neural Comput. 3, 79–87 (1991).

Jacobs, R. A., Jordan, M. I. & Barto, A. G. Task decomposition through competition in a modular connectionist architecture: The what and where vision tasks. Cogn. Sci. 15, 219–250 (1991).

Berl, M. M. et al. Characterization of atypical language activation patterns in focal epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 75, 33–42 (2014).

Maldjian, J. A., Laurienti, P. J., Kraft, R. A. & Burdette, J. H. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. Neuroimage 19, 1233–1239 (2003).

Amunts, K. Structural indices of asymmetry. In The two halves of the brain 145–176 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our participants and their families for their valued contributions to our scientific progress. We would also like to thank our colleagues for their helpful input on our work in its various stages over time, including Drs. Barbara Landau, Maximilian Riesenhuber, Ella Striem-Amit, Bradley Schlaggar, and Andrew DeMarco. This work was supported by funds from Georgetown University and MedStar Health and by the Solomon James Rodan Pediatric Stroke Research Fund, the Feldstein Veron Innovation Fund, and the Bergeron Visiting Scholars Fund to the Center for Brain Plasticity and Recovery; by NIH Grants K18DC014558 to E.L.N. and R01DC016902 to E.L.N. and W.D.G.; by American Heart Association Grant 17GRNT33650054 to E.L.N.; by NIH Grant P50HD105328 to the District of Columbia-Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center at Children’s National Hospital and Georgetown University; by NIH/OD “Prisma Upgrade for a Siemens 3T MRI Scanner” S10OD023561; and by NIH Grant T32NS041218 to K.C.M via Georgetown University’s Center for Neural Injury and Recovery.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.C.M. (Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing), A.S-G. (Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing), P.E.T. (Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing), C.E.C. (Data curation, Project administration), W.D.G. (Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Writing—review and editing), E.L.N. (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing—review and editing).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, K.C., Seydell-Greenwald, A., Turkeltaub, P.E. et al. Functional partitioning of sentence processing and emotional prosody in the right perisylvian cortex after perinatal stroke. Sci Rep 14, 28602 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79302-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79302-5