Abstract

Cyanobacterial phycobiliproteins, such as phycoerythrin (PE) and phycocyanin (PC), are colored potential bioactive proteins that have antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. In this study, we formulated a new food prototype based on PE and PC-fortified low-fat yogurt and cream cheese. Four distinct low-fat yogurt and cream cheese products were manufactured, including a control group (No PE and PC), samples produced with phycoerythrin (+ PE), samples produced with phycocyanin (+ PC), and samples produced with both phycoerythrin and phycocyanin (PC + PE). Afterwards statistically compared the physicochemical composition, colorimetric properties, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, and sensory profile of the fortified foods at 4 °C and 8 °C for 28 and 42 days. Additionally, we confirmed that PE and PC are not toxic to Caenorhabditis elegans at concentrations up to 1 mg/mL. The results showed that the MIC of PE and PC against E. coli was significantly higher than against S. aureus (3.12 ± 0.05 µg/mL vs. 1.56 ± 0.01 µg/mL, respectively; p ≤ 0.05). Additionally, the maximum diameter of the inhibition zone of PE and PC against S. aureus was significantly higher than against E. coli (6.6 ± 0.011 mm vs. 11.66 ± 0.02 mm, respectively; p ≤ 0.05). Results of color parameters showed that the control group had significantly higher L* values than the samples enriched with PE and PC. Moreover PE and PC significantly increased the a* and b* values respectively. The amount of ΔE in the control yogurts and cream cheese was higher than in the samples with PE and PC. Overall, the results showed that adding PE and PC had a significant effect on all measured factors (p < 0.01). Cream cheeses and low-fat yogurts enriched with either PE or PE + PC had the greatest antioxidant activity and the lowest number of psychrophilic bacteria and mold, and yeast counts at the end of the test period. Therefore, low-fat yogurt and cream cheese containing cyanobacterial PE and PC can be considered an innovative dairy product for the food industry. This study marks the initial effort to employ PE and PC derived from Nostoc sp. and Spirulina sp. as antioxidant and antimicrobial agents in the food industry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cyanobacteria are a group of photosynthetic prokaryotes that can produce oxygen through photosynthesis, similar to plants. They are globally recognized for their potential use as bio-fertilizers, food, biopolymers, and biofuels. They can also produce various secondary metabolites, enzymes, vitamins, and pharmaceuticals, and can help reduce pollution1,2.

The important part of the pigments or photosynthetic pigments of cyanobacteria are phycobiliproteins (PBPs). Four types of phycobiliproteins are found in cyanobacteria: PC, PE, allophycocyanin (APC), and phycoerythrocyanin (PEC)3. PBPs are water-soluble proteins that are responsible for collecting light in cyanobacteria and may include more than half of the total soluble proteins in these microorganisms4. These colored proteins are classified into three categories based on their spectroscopic characteristics: PE ( with a maximum wavelength of 656 nm), PC (with a maximum wavelength of 620 nm), and APC (with a maximum wavelength of 650 nm). Meanwhile, PE and PC pigments are well known for having antimicrobial and antioxidant properties5,6,7.

Antioxidants are natural or artificial substances that can prevent or delay the oxidation of oxidizable substances in cells, or preserve the quality of food by preventing oxidative deterioration of lipids8 These compounds function by removing reactive oxygen species (ROS) or activating detoxification proteins to prevent the production of ROS. ROS are natural metabolites that include nitric oxide radical, superoxide anion radical, hydroxyl radical, and hydrogen peroxide9.

Small amounts of ROS cause harmful changes in cell function, including lipid peroxidation, enzyme inactivation, and DNA oxidative damage. Oxidative stress, caused by these molecules, can damage cells, proteins, and the genome. This damage has been shown to play a role in aging and the development of diseases such as cancer, atherosclerosis, and neurodegenerative disorders10.

Cells have antioxidant defense mechanisms that protect them from the harmful effects of free radicals and oxidative stress. To meet this need, many artificial and synthetic antioxidants have been introduced into the market, including butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), tert-butyl hydroquinone (TBHQ), and propyl gallate (PG). However, the use of synthetic preservatives is a major concern in the food industry11. The use of synthetic antioxidants has been greatly reduced since they are carcinogenic compounds, and this reduction is also evident in the use of artificial additives12. To prevent the oxidative degradation of food and reduce the oxidative degradation of living cells, scientists worldwide are currently working to isolate new and safe antioxidants from natural sources, such as cyanobacteria13. For this reason, all food laboratory research in developed countries is in the field of natural preservatives, and the results of this research are transferred to industrial pilots.

One of the biggest challenges in the food industry is extending the shelf life of perishable food products14. On the other hand, the use of synthetic preservatives is completely limited for consumers due to some of their risk effects, including their carcinogenicity15. A suitable preservative should be chosen for food products16.

Yogurt and cheese with high nutrient content and vulnerable packaging provide suitable conditions for the growth of microbes. Cheese and yogurt are valuable products of milk fermentation, which are rich in protein, calcium, and phosphorus17. There are over 1300 different types of cheese in the world, and the milk of various types of dairy animals is widely used for cheese making18. In other words, cheese is a product that can be made in various textures (soft, semi-hard, hard, and very hard) while the ratio of serum protein to casein should not exceed the ratio in milk18.

Cream cheese is a type of soft, spreadable, and unripened cheese that has a doughy and spreadable texture. In the process of cream cheese, starter bacteria, and rennet are added to pasteurized and homogenized milk whose fat has been standardized, and after lactic fermentation and curd formation, the curd is dewatered by centrifugal force or filter system19.

Yogurt is a dairy product that is produced by fermentating milk using Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus20. According to the standard definition, yogurt is a coagulated product that is obtained from acid fermentation of pasteurized milk by specific lactic bacteria in a significant amount and at a specific temperature and time. Yogurt is obtained by adding lactobacillus starter cultures to milk, in flavored yogurt it is obtained after adding edible flavorings or without additional raw materials21.

There are various types of flavored yogurts, including molded flavored yogurt. After being flavored, this type of yogurt goes through the stages of coagulation, warming, and cooling in suitable and desired containers. The yogurt then adopts the shape and form of the container22. Stirred flavored yogurt is another type of yogurt that undergoes the stages of greenhouse and coagulation. Afterward, all kinds of permitted flavorings are added and mixed to it. The third type is flavored condensed yogurt, which is made by removing part of the serum or adding solids from milk to the yogurt. It is then flavored with a variety of food flavorings23.

The microbiology characteristics of different types of flavored yogurts must comply with the Iranian National Standard No. 2406 on the microbiology of milk and its products24.

Yogurt and cheese are rich in nutrients, making them ideal breeding grounds for bacteria, which can cause them to spoil25. In addition, the improper temperature of refrigerators may turn them into highly perishable products. Commercial cheeses and yogurts have a specific shelf life. Thus, this study aims to investigate the possibility of increasing the shelf life of these products by adding natural edible pigments (PE, PC) which are also rich in antimicrobial and antioxidant compounds26.

A recently published study has shown the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of Nostoc sp. and Spirulina sp. cyanobacteria which are rich in PE and PC pigments, respectively27.

Moreover, the review of the literature showed that there have been many reports on the investigation of PC pigment isolated from Spirulina cyanobacteria28,29,30,31. Therefore, in this paper, PE is used as a dominant pigment of Nostoc cyanobacteria, in addition to PC pigment. Also, the combination of these two pigments (PE, PC) was used for the first time to increase the shelf life of flavored low-fat yogurt and commercial cream cheese in the market. Considering the antioxidant and antimicrobial potential of edible PE and PC, one of the objectives of this study is to examine the impacts of these pigments on increasing the shelf life of yogurt and cheese.

Materials and methods

Materials

The Nostoc sp. and Spirulina sp. cyanobacteria strains were obtained from the cyanobacteria culture collection of Azad University, Science and Research Unit, Cyanobacteria culture collection (CCC), located in Alborz Herbarium.

Methods

Cultivation of cyanobacterial strains

Purified samples were cultivated in BG110 and Zarrouk liquid culture media for 30 days at 28 ± 2 °C in a growth chamber under continuous fluorescent light with an intensity of 300 microns per square meter per second32,33.

Extraction of phycoerythrin and phycocyanin

To extract PE and PC, 500 ml of the 14-day culture medium of BG110 and Zarrouk liquid containing Nostoc sp. and Spirulina sp. were centrifuged at 5000 rpm, and the precipitates were washed with phosphate buffer (pH: 7.2). Two grams of fresh biomass containing both strains were then suspended in 0.5 L of 0.1 M sodium phosphate reagent34.

The extraction of PE and PC was carried out by repeating the freezing (− 20 °C) and thawing (24 °C and darkness) method35. The resulting mixture was left to stand for 12 h at a cold room temperature of 0–10 °C and then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 7 min. The pellets were resuspended in 2 ml of 50 mM acetic acid-sodium acetate buffer and dialyzed overnight against ten times the volume of the same buffer. The extract obtained from the dialysis membrane was then filtered through a 0.45 μm filter.

Adding a preservative and spectroscopy

To prepare the PE and PC solution, 0.1 g of citric acid was added to 25 ml of the solution (pH 7.2) obtained in the previous step. Another solution was produced by adding 0.1 g of citric acid to the combination of PC and PE solution, with a total volume of 10 ml.

Spectroscopy was performed at a wavelength range of 250–700 nm (Shimidazu 1800, Japan)35. The purity percentage and pigment concentration were determined using the following formula, with the absorption maxima of 620 nm (PE), 565 nm (PC), and 650 nm (APC) used for calculation36:

\({\text{~PE }}\left( {\mu {\text{g/ml}}} \right)=\frac{{({\text{OD~}}565{\text{nm}} - 2.8\left[ {{\text{R}} - {\text{PC}}} \right] - 1.34\left[ {{\text{APC}}} \right])}}{{12.7}}\)

Pureness of PE and PC was determined at each phase as purity ratio (A555/A280) and (A620/A652) respectively37.

Investigation of antibacterial activity

The agar well diffusion method was performed according to a previous study38. E. coli ATCC No.25,922 and Staphylococcus aureus PTCC No.1112 were spread uniformly on Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA) plates. Wells with a diameter of 6 mm were made on the culture via a gel punch. Fifty µl of PE and PC solution at different concentrations (2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 25 µg/ml) were transferred to each well. After incubation at 35 °C for 24 h, the diameter of the inhibitory zones (nm) was noted. Sterilized distilled water (as a negative control), tetracycline, and amikacin both at 30 mg disc (as a positive control for gram-positive bacteria), and doxycycline at 30 mg disc for both groups were used. All experiments were performed in triplicate according to Gheda et al.38.

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) standard method (CLSI 2012) was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). Different dilutions of PE and PC extract (100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12, 1.56, 0.78, 0.39, and 0.19 µg/ml) were used to determine the lowest concentration of PE and PC that inhibited the growth of E. coli ATCC No.25,922 and S. aureus PTCC No.1112 (CLSI 2012).

Toxicity assays of PE and PC

Wild-type C. elegans var. Bristol-N2 was gifted from the Pasteur Institute of Tehran, Iran. Nematode growth agar was used to culture C. elegans. Eggs were deposited on agar plates for 48 h, and young larvae were harvested and suspended in M9 worm buffer. The toxicity test of the PE and PC mixed solution from Nostoc sp. and Spirulina sp. was evaluated at concentrations of 0, 0.125, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 mg/ml. The nematode without PE and PC was used as a control. Quadruplicate tests were carried out for 24 h at 18 °C39.

Preparing low-fat yogurt and cream cheese

Based on the MIC results, inoculation tests were performed on low-fat yogurt and cream cheese, which were then kept at + 8 and + 4 °C for treatments40. The process of cream cheese production from retentate (16.0% fat and 33.5% dry matter) was similar to the method described by Valikboni et al. (2024) with some modifications. To prepare cheese, fresh milk (1 L 16.0% fat and 33.5% dry matter) was heated at 70 milk (1 L 16.0% fat and 33.5%te cooled to achieve a temperature of 35 to 40 and 33.5%ter) acetic acid per 1-L milk, and stirred for 15 s. Then, salt (1%)and starter bacteria of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis and Lactococcus lactis subsp. Cremoris (1 g) were added to the 10 L of milk at 40 theter bacter About 1/4 tablets of rennet was diluted in 1-mL water and added to a mixture of milk and acetic acid. Allow the milk added with rennet for 1 h to become fermented fresh cow milk and then cut so that they can be easily exerted, and wait for 5 min. Fermented fresh cow milk was drained by using stainless steel bowl, and then poured hot water (30 mL) to accelerate the whey production and drained again. Afterwards, kept refrigerated at 4 ined ag42 days41.

Yogurt preparation was based on pasteurized fresh cow’s milk as raw material. The milk formulation was composed of sugar at 7% (w/v) and gelatin as thickener at 0.5% (w/v). Milk were heated for 20 min at 85 °C and then cooled to 40 °C. A commercial starter culture YC-X11 (Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus) was mixed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Chr. Hansen, Denmark) and added to the samples. After mixing well and transferring into plastic cups. all samples were incubated at 43 °C for 4 h. The pH and acidity were determined every hour during fermentation. After fermentation, the yogurt samples were cooled and kept at 4 °C for 28 days42.

Four distinct low-fat yogurt and cream cheese products were manufactured, including a control group (No PE and PC), samples produced with phycoerythrin (+ PE), samples produced with phycocyanin (+ PC), and samples produced with both phycoerythrin and phycocyanin (PC + PE).

According to the results of the MIC, low-fat yogurt and cream cheese were marinated in the food-grade purified PE and PC at a final concentration of 1.56 and 3.12 µg/mL, respectively. Low-fat yogurt was tested on 0, 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days, while cream cheese was tested on 0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 days after the above-mentioned interval storage time at two different temperatures (+ 8 and + 4 °C). Sampling was done, and the microbial and chemical properties were determined.

Color parameters

The color of low-fat yogurt was assessed using a Chroma meter cr-400 (Konica Minolta, Japan) on days 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28, while the color of cream cheese was determined on days 1, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 at + 4 °C. The L*, a*, and b* values correspond to whiteness, redness, and yellowness, respectively. Color analysis was repeated three times for each sample43,44. The Delta E (ΔE) metric was used to quantify the perceived color difference between samples, using the following formula:

\({\text{DE}}=\surd {\left( {{\text{L1}} - {\text{ L2}}} \right)^{\text{2}}}+{\text{ }}\left( {{\text{ a1}}\, - \,{\text{a2}}} \right){\text{2 }}+{\text{ }}{\left( {{\text{b1}} - {\text{b2}}} \right)^{\text{2}}}\)

L* = Lightness a* = Redness-greenness b* = Yellowness-blueness ΔE = Difference in color measurement between the two samples.

Chemical properties of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese

Total solids, carbohydrates, protein, salt, fat, and moisture contents of samples were evaluated according to the Official Methods of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists18. Phytosterols were quantified using the previously described method45.

Microbial analyses

To assess the microbial quality of the samples, the following parameters were evaluated using standard methods: total psychrophilic bacteria count (ISO 4833-1: 2013), coliform count (ISO 4832: 2006), mold and yeast count (ISO 6611: 2004), E. coli count (ISO 9308-2: 1990), and positive coagulase Staphylococci count (ISO 6888-3:2003).

Additionally, Xylose Lysine Deoxycholate (XLD) Agar (a selective medium for Salmonella and Shigella) was used to detect these pathogens. Sulfite-reducing clostridia in SPS agar tubes which sealed with sterile paraffin and kept at 37 °C for overnight, while black mottled was considered as a positive result46.

Measurement of antioxidant potential

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) method

A modified method, used by47 was performed on days 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 for low-fat yogurt and 1, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42 days for cream cheese. Firstly, the FRAP working solution was prepared as described by Ulloa et al.48. After heating 1.5 mL of the solution to 37 °C, its absorbance was measured at 600 nm. Twenty-five µL of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt were mixed with 9 mL of methanol, centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 min, and the top 20 µL of extract was removed and transferred to a 1 mL vial.

The FRAP assay was performed by measuring absorbance changes at 600 nm and 37 °C for 5 min. After subtracting blank absorbance, the amount of FRAP was converted to Trolox equivalent/L µmol utilizing a Trolox standard curve.

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) method

The DPPH method was used to evaluate the antioxidant activity of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese. The modified method used by Guerreiro et al.49 was performed on low-fat yogurt for days 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 and on cream cheese for days 1, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42. Twenty-five µL of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt were mixed with 2 ml of 4% DPPH solution. The mixture was placed in a dark place for 10 min, and the absorption spectra of each tube, including the blank tube, were read with a 517 nm spectrometer (Shimadzu UV-1800, Japan). The inhibition percentage was determined using the following formula:

\(\left( {{\text{Adsorption sample }} - {\text{ Adsorption blank}}} \right)/\left( {{\text{Adsorption blank}}} \right){\text{ }} \times {\text{ 1}}00\)

The IC50 was also determined based on the equation obtained in the data analysis.

ABTS assay

The ABTS radical cation scavenging assay was performed on low-fat yogurt for days 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 and on cream cheese for days 1, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42, following the method of Sarkar et al.50 with some modifications. Briefly, ABTS + radicals were generated, and 3 mL of the ABTS + solution (7 mM) was added to 25 µL of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese samples. The absorbance was measured at 734 nm against ethanol as a blank. ABTS + solution was used as a positive control, and butylated hydroxytoluene was used to calibrate the standard curve.

The activity (%) was calculated using the following formula:\({\text{Activity }}\left( \% \right){\text{ }}={\text{ }}\left( {{\text{Ac}}\, - \,{\text{At}}} \right){\text{ }}/{\text{ Ac }} \times {\text{ 1}}00\). Where “At” was the absorbance of the sample, and “Ac” was the absorbance of ABTS.

Sensory assessment

Sensory evaluation of enriched yogurt and cheese was performed according to the IDF standard (International IDF standard 99 C: 1997). Thirty food industry experts who were fully acquainted with the qualities of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese at both + 4 °C and + 8 °C evaluated the samples in terms of odor, flavor, color, texture, and general acceptance. The sensory evaluation was conducted on low-fat yogurt for days 1, 4, 7, 14, 21, and 28 and on cream cheese for days 1, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, and 42.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 24 (IBM Corporation Inc.) at a significance level of 95%. The Tukey test was used to compare mean values when the ANOVA test indicated a significant difference (p < 0.05). Each treatment was replicated three times, and the mean values ± standard error of the mean were calculated.

Results

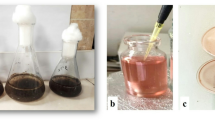

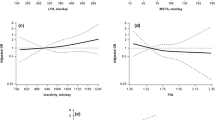

Extraction, purification, and characterization of PE and PC

The concentration and purity of PE and PC were monitored at each purification step, as shown in Table 1; Fig. 1. The concentration of both PE and PC increased after each purification step. During successive purification steps, adding 0.1 g of citric acid (as a preservative) increased the purity ratio of PE from 0.845 to 5.20 and the purity ratio of PC from 0.401 to 3.21. The precipitated reddish-pink and blue-colored proteins were dissolved in phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), which showed absorption maxima at 562 nm with a shoulder peak at 617 nm for PE and an absorption maximum at 621.9 nm for PC (Figs. 2 and 3). These spectra are typical for PE and PC, respectively.

Evaluation of inhibition zone diameter and MIC of the purified PC and PE

Table 2 shows the results of comparing the average inhibition zone diameter and MIC of PE and PC against E. coli and S. aureus. The results showed that the MIC of PE and PC against E. coli was significantly higher than against S. aureus (3.12 ± 0.05 µg/mL vs. 1.56 ± 0.01 µg/mL, respectively; p ≤ 0.05). Additionally, the maximum diameter of the inhibition zone of PE and PC against S. aureus was significantly higher than against E. coli (6.6 ± 0.011 mm vs. 11.66 ± 0.02 mm, respectively; p ≤ 0.05).

Toxicity of PE and PC against C. Elegans

C. elegans survival rates were not affected by PE or PC, with 100–96.1% survival at all concentrations used (Table 3).

Color measurement

Color parameters of L* (lightness), a* (green-red value), and b* (blue-yellow value) of low-fat cream cheese and yogurt samples were determined at 4 °C.

L* values decreased over time for all samples, indicating that the samples became darker. The control group had significantly higher L* values than the samples enriched with PE and PC at the beginning of storage, but the enriched samples had the highest L* values by the end of storage. In addition, a* values increased over time for all samples, indicating that the samples became more red. Enriched cream cheese samples had significantly higher a* values than the control group at both the beginning and end of storage. Adding PE significantly increased the a* values of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt samples to positive values, indicating that the samples became more reddish. Moreover, b* values (yellowness) increased over time for all samples. The control group had the lowest b* value at the beginning of storage. Adding PC significantly increased the b* values of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt samples compared to the other treatments, indicating that the samples became more yellow.

The variance in color quantity (ΔE) between the control group and enriched cream cheese showed the highest value (24.69 ± 0.16) for the control group compared to the enriched cream cheese with both PE and PC, which had the lowest value (9.53 ± 0.12). The amount of ΔE in the control yogurts was higher than in the yogurts with PE and PC, while there was no significant difference in the amount of ΔE between the yogurts enriched with PE and PC (Tables 4 and 5).

Chemical analysis

The salt, protein, and fat content of the samples were not significantly affected by adding PE and PC on the first day of the experiment (Table S3). The pH of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese increased after 28 and 42 days of storage at both temperatures (+ 4 °C and + 8 °C), with a greater decrease at + 8 °C than at + 4 °C. On the last day of storage, the pH of enriched low-fat yogurts and cream cheeses with PE at + 4 °C was significantly lower than the other treatments (Tables S4 and S5). The titratable acidity of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese also increased after 28 and 42 days of storage at both temperatures, with a greater increase at + 8 °C than at + 4 °C. On the last day of storage, the titratable acidity of enriched low-fat yogurts and cream cheeses with PE and PE + PC at + 4 °C and + 8 °C was significantly lower than the other treatments (Tables S6 and S7). The total solids of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese increased after 28 and 42 days of storage at both temperatures. On the last day of storage, the total solids of enriched low-fat yogurts and cream cheeses were significantly lower than the control (Tables S8 and S9). The moisture content of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese decreased after 28 and 42 days of storage at both temperatures. On the last day of storage, the moisture content of enriched low-fat yogurts and cream cheeses was significantly higher than the control (Tables S10 and S11). Phytosterols were not detected in low-fat yogurt and cream cheese under the given analytical conditions.

Microbiological analysis

The total psychrophilic bacteria counts in low-fat yogurt and cream cheese significantly increased from day 3 of storage at 4 °C and 8 °C to reach a maximum on days 28 and 42 days. The increase in the number of total psychrophilic bacteria counts was reported more at + 8 °C in comparison to + 4 °C. In total, the number of total psychrophilic bacteria counts in low-fat yogurt and cream cheese enriched with PE and (PC + PE) was significantly lower than the other treatments (Tables 6 and 7). Mold and yeasts were found in control and enriched cream cheese at 4 °C on days 21 and 42 respectively. In enriched low-fat yogurt at 4 °C, fungi were found on days 14 and 7. Moreover, at 8 °C, they were found on days 14 and 21 in control and enriched cream cheese respectively. While in enriched low-fat yogurt at 8 °C, fungi were found on days 21 and 14.

In total, the number of mold and yeasts of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt enriched with PC + PE at both 4 °C and 8 °C was significantly lower than the other treatments (Table S12 and S13). Total coliforms were found only in control cream cheese at 4 °C on day 42, while they were not found in control and enriched low-fat yogurt at 4 °C. However, at 8 °C, they were found on days 35 and 42 in control and enriched cream cheese respectively. While they were found on days 21 and 28 in only control low-fat yogurt. Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, positive coagulase Staphylococci, and Sulphite-reducing clostridia were not detected in low-fat yogurt and cream cheese during the first 28 or 42 days of storage.

Results of antioxidant activity

The results of the FRAP method showed that the amount of antioxidant activity of enriched low-fat yogurt and cream cheese decreased at both temperatures of 4 °C and 8 °C with a very low slope and with a significant difference until the end of the 28th and 42nd day (Tables 8 and 9). The highest amount of antioxidant activity enriched in low-fat yogurt and cream cheese with a significant difference in both temperatures belongs to cheeses enriched with PE (p ≤ 0.05). However, no significant difference in antioxidant activity (DPPH and ABTS) was seen between the different treatments of PE, PC, and PE + PC in both tested samples (low-fat yogurt and cream cheese) (Tables S14-S17).

The sensory values

The sensory values (color, odor, flavor, and texture) of enriched cream cheese and low-fat yogurt during 28 and 42 days of storage at 4 °C and 8 °C were presented in Figs. 4 and 5, respectively. The level of consumer satisfaction with enriched cream cheese and low-fat yogurt during 28 and 42 days of storage at 4 °C and 8 °C decreased significantly. The highest level of consumer satisfaction belongs to the cheeses and low-fat yogurt enriched with PE + PC, which has the highest score compared to other treatments at both temperatures.

Discussion

Cyanobacterial PBPs are used by the food industry to enrich a variety of products, including biscuits, nutritional bars, juices, pasta, bread, and dairy products39. Due to the growing concern about the harmful effects of artificial food colors, the food industry has increasingly turned to using natural and functional pigments in recent years42,51.

Yogurt and cheese are popular dairy products worldwide due to their nutritional value. Some studies have explored the use of microalgal biomass in yogurt and cheese due to its high content of pigments and compounds with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties19,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66.

The stability of the purified PE and PC from two Nostoc strains was measured after incubation at different temperatures and food-grade preservatives by Nowruzi and Jafari Porzani in 2022. Citric acid was found to be the most effective preservative for stabilizing the grade PE and PC over time67. Its use is essential for the commercial viability of the process, given the extreme sensitivity of these materials. Our findings showed that adding citric acid as an additive, increased the purity and concentration of PE by 5.20 (after dialysis) and 0.845 (crude extract), and the purity and concentration of PC by 0.401 (crude extract) and 3.21 (after dialysis). These findings demonstrate the effectiveness of citric acid in purifying PE and PC to high purity.

Caenorhabditis elegans was used for toxicity evaluation of PE and PC because it is an easy and inexpensive species to culture in the biology laboratory. Moreover, it has a short life cycle that allows for short-time span experiments, and there is increasing evidence of its genetic and physiological similarity with mammals5.

C. elegans was chosen for toxicity assessment of PE and PC in this study because it is an easy and reasonable model organism to culture in the laboratory. It also has a short life cycle, which allows for rapid experiments, and its genetic and physiological similarity to mammals is increasingly being recognized. The results showed that neither PE nor PC were toxic to C. elegans, which is consistent with previous findings by Ju et al.68.

Silva et al. found that adding A. platensis to yogurt after fermentation did not significantly change the fat or carbohydrate content of the yogurt, likely because A. platensis has very low levels of fat and carbohydrates29,56. The findings of this study are in agreement with the achievement of Silva et al., since the percentage of salt, protein, and fat content on the first day was not significantly affected by adding PE and PC in comparison with the control. In a study by Mohammadi et al.19, increasing the pH values in PC-fortified yogurts was reported. The findings of the current study align with previous research on the buffering capacity of proteins, peptides, and amino acids, such as PE and PC29,56.

However, on the last day of the experiment, the pH level in enriched low-fat yogurts and cream cheeses with PE at + 4 °C was significantly lower than the other interval day treatments. Changes in pH at the end of storage may be due to the production of metabolites such as amino acids and bacteriocins from PE. The most important point is that the pH and titratable acidity levels in low-fat yogurt and cream cheese are within the standard range according to the Iranian National Standardization Organization at 42 and 27 days, respectively.

Moreover, the moisture contents in enriched low-fat yogurts and cream cheeses were significantly increased 1.06–1.05 times that of the controls at + 4 °C and + 8 °C, respectively. This finding is in contrast to the results of Golmakani et al. (2019), who found that the hardness of all cheeses increased significantly after 60 days of storage, which they attributed to the lower final moisture contents of the samples (0.85–2.78%)65.

Consumers are widely accepting food products supplemented with microalgal natural pigments, which improve color and antioxidant properties69,70,71,72.

Yogurt color is a key characteristic that drives consumer acceptance. Studies using the CIELab scale (L, a, b*) have shown that adding microalgae affects the final product color73.

Studies have shown that adding microalgae to yogurt can change its color. For example, Barkallah et al.55 found that yogurt enriched with 0.25% A. platensis powder had lower values of a* and b* on the CIELab scale, indicating a shift from yellow to greenish. This is because A. platensis contains a high concentration of chlorophyll. Robertson et al.54 also observed a similar trend in yogurt fortified with 0.25% and 0.5% Pavlova lutheri after 28 days of storage54.

Our findings revealed that L* values of cheese and yogurt enriched by both PE and PC on the last day of treatment (42nd day) were 1.069 and 1.02 times that of the controls, respectively. Adding PE significantly increased the a* values of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt to 2.87 and 5.66 times that of the controls, respectively. Furthermore, adding PC significantly increased the b* values of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt compared to 1.68 and 2.30 times that of the controls, respectively. Moreover, the value of (ΔE) in enriched cream cheese and low-fat yogurt was significantly decreased by 2.59 and 1.87 times that of the controls, respectively.

Previous studies have shown that purified PE and PC have antioxidant capabilities39,49,74,75. In the current study, the antioxidant activity of PE and PC-fortified low-fat yogurt and cream cheese was evaluated by three assays: (i) The FRAP assay can detect antioxidants that contain iron (II) or SH groups76, (ii) DPPH method uses organic radicals77, and (iii) ABTS was based on the ability of antioxidant compounds/extracts to scavenge ABTS + radical cations78. So, combining these three methods should provide an accurate and comprehensive measure of the antioxidant activity of PC and PE in samples.

The FRAP assay is an important indicator of the antioxidant potential of a sample79. The results of our FRAP assay showed that enriched low-fat yogurt and cream cheese with PE produced high antioxidant activity in comparison to other antioxidant assays. Antioxidant activity in enriched cream cheese with PE on 42 days was significantly higher, 2.34 and 2.75 times that of the controls at + 4 °C and + 8 °C respectively. Moreover, antioxidant activity in enriched low-fat yogurt with PE on 28 days was significantly higher, 1.71 and 1.8 times that of the controls at + 4 °C and + 8 °C respectively. These results suggest that the antioxidants in PE extracted from Nostoc sp. have more phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and lipophilic properties than the others. However, the results obtained by FRAP assay were not supported with DPPH and ABTS assays. Moreover, the inhibition zone diameter of PE against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus was 1.85 and 1.76 times that of the PC. These results are in agreement with the number of total psychrophilic bacteria counts of cream cheese enriched with PE and (PC + PE) since it was significantly decreased on 42 days, 0.71 and 0.8 times that of the controls at + 4 °C and + 8 °C respectively. However, the number of total psychrophilic bacteria counts of low-fat yogurt enriched with PE and (PC + PE) was significantly decreased on 28 days, 0.83 and 1.27 times that of the controls at + 4 °C and + 8 °C respectively. The number of mold and yeasts of cream cheese and low-fat yogurt enriched with PC + PE at both 4 °C and 8 °C was within the standard range according to the Iranian National Standardization Organization at 42 and 27 days respectively80.

Microalgae are also being added to dairy products as a source of bioactive and coloring compounds, and consumers are generally accepting of these products, especially in terms of their texture and appearance39. In this study, a panel of volunteers evaluated prototypes of low-fat yogurt and cream cheese fortified with PC and PE using a hedonic scale. The fortified products had higher consistency scores than the control, but the differences were not statistically significant. However, the highest score for odor, flavor, color, and texture stood out in PE + PC fortified cream cheese and low-fat yogurt. It should be introduced as a suitable substitute for synthetic antimicrobials and antioxidants, which not only does not pose any danger to the consumer but also improves the health of consumers due to its antimicrobial and antioxidant properties.

Conclusion

Microalgae are gaining attention as a promising source of nutraceutical and functional compounds for developing sustainable foods with improved nutritional profiles and health benefits. Fermented dairy foods are also popular, as they contain microorganisms with health-promoting effects.

In this study, the researchers used Nostoc sp. and Spirulina sp. strains to purify PE and PC, respectively, and added them to low-fat yogurt and cream cheese as colorants, antimicrobials, and antioxidants. They also reported the toxicity of the purified PBPs and the sensory test results of the final products.

We found that incorporating PE and PC into low-fat yogurt and cream cheese is a complex process that requires careful consideration of many factors, such as antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, sensory quality, and proteolysis. For example, proteolysis that occurred during the storage of samples may have caused the accumulation of peptides that give dairy products a bitter taste. Different methods could be used to reduce the algae-like aroma, such as the inclusion of beta-cyclodextrins, fermentation, enzymatic hydrolysis, solvent extraction, and heating. The best method for removing undesirable attributes in the final product should be determined on a case-by-case basis. Overall, the study revealed that PE and PC have the potential to be used as colorants, antimicrobials, and antioxidants in low-fat yogurt and cream cheese. However, further research is needed to optimize the incorporation process and develop methods to reduce the algae-like aroma.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Change history

05 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-87903-x

References

Zahra, Z., Choo, D. H., Lee, H. & Parveen, A. Cyanobacteria: review of current potentials and applications. Environments 7, 13 (2020).

Righini, H., Francioso, O., Martel Quintana, A. & Roberti, R. Cyanobacteria: a natural source for controlling agricultural plant diseases caused by fungi and oomycetes and improving plant growth. Horticulturae 8, 58 (2022).

George, R. & John, J. A. Phycoerythrin as a potential natural colourant: a mini review. IJFST 58, 513–519 (2023).

Stadnichuk, I., Krasilnikov, P. & Zlenko, D. Cyanobacterial phycobilisomes and phycobiliproteins. Microbiology 84, 101–111 (2015).

Nowruzi, B., Konur, O. & Anvar, S. A. A. The stability of the phycobiliproteins in the adverse environmental conditions relevant to the food storage. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 15, 2646–2663 (2022).

Nowruzi, B. Cyanobacteria natural products as sources for future directions in antibiotic drug discovery. Recent Adv. New Perspect. (2022).

Nowruzi, B., Sarvari, G. & Blanco, S. In Handbook of Algal Science, Technology and Medicine441–453 (Elsevier, 2020).

Shahidi, F. & Zhong, Y. Novel antioxidants in food quality preservation and health promotion. EJLST 112, 930–940 (2010).

Jomova, K. et al. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 1–76 (2023).

Amiri, M. Oxidative stress and free radicals in liver and kidney diseases; an updated short-review. J. Nephropathol 2018, 7 (2018).

Sharif, Z., Mustapha, F., Jai, J. & Zaki, N. Review on methods for preservation and natural preservatives for extending the food longevity. Chem. Eng. Res. Bull. 19, 58 (2017).

Amin, K. A. & Al-Shehri, F. S. Toxicological and safety assessment of tartrazine as a synthetic food additive on health biomarkers: a review. AJB 17, 139–149 (2018).

Dey, S. & Nagababu, B. H. Applications of food color and bio-preservatives in the food and its effect on the human health. Food Chem. Adv. 1, 100019 (2022).

Mendes, A., Cruz, J., Saraiva, T., Lima, T. M. & Gaspar, P. D. In 2020 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application (DASA) 173–178 (IEEE, 2024).

Cao, Y. et al. Impact of food additives on the composition and function of gut microbiota: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 99, 295–310 (2020).

Wu, L. et al. Food additives: from functions to analytical methods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 8497–8517 (2022).

Tessier, A. J. et al. Milk, yogurt, and cheese intake is positively associated with cognitive executive functions in older adults of the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. J. Gerontol. A 76, 2223–2231 (2021).

AOAC. AOAC International Rockville, MD, USA (2016).

Mohammadi-Gouraji, E., Soleimanian-Zad, S. & Ghiaci, M. Phycocyanin-enriched yogurt and its antibacterial and physicochemical properties during 21 days of storage. Lwt 102, 230–236 (2019).

Moniente, M. et al. Potential of histamine-degrading microorganisms and diamine oxidase (DAO) for the reduction of histamine accumulation along the cheese ripening process. Int. Food Res. 160, 111735 (2022).

Jafari, M., Shariatifar, N., Khaniki, G. J. & Abdollahi, A. Molecular characterization of isolated lactic acid bacteria from different traditional dairy products of tribes in the Fars province, Iran. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 11, e3621–e3621 (2021).

Fan, X. et al. The effect of natural plant-based homogenates as additives on the quality of yogurt: a review. Food Biosci. 2022, 101953 (2022).

Su, N. et al. Antioxidant activity and flavor compounds of hickory yogurt. Int. J. Food Prop. 20, 1894–1903 (2017).

Ghasemloy Incheh, K. et al. A survey on the quality of traditional butters produced in West Azerbaijan province, Iran. Int. Food Res. 2017, 24 (2017).

Fan, X. et al. Markers and mechanisms of deterioration reactions in dairy products. Food Eng. Rev. 2023, 1–12 (2023).

Heller, K. J. Probiotic bacteria in fermented foods: product characteristics and starter organisms. AJCN 73, 374s–379s (2001).

Nowruzi, B., Haghighat, S., Fahimi, H. & Mohammadi, E. Nostoc cyanobacteria species: a new and rich source of novel bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical potential. JPHSR 9, 5–12 (2018).

Shafaei Bejestani, M., Anvar, A. A., Nowruzi, B. & Golestan, L. Production of cheese and ice cream enriched with biomass and supernatant of Spirulina platensis with emphasis on organoleptic and nutritional properties. Iran. J. Vet. Med. (2023).

Davoodi, M., Amirali, S., Nowruzi, B. & Golestan, L. The effect of phycocyanin on the microbial, antioxidant, and nutritional properties of Iranian cheese. Int. J. Algae 25, 859 (2023).

Anvar, A. & Nowruzi, B. Bioactive properties of spirulina: a review. Microb. Bioact 4, 134–142 (2021).

Antelo, F. S., Anschau, A., Costa, J. A. & Kalil, S. J. Extraction and purification of C-phycocyanin from Spirulina platensis in conventional and integrated aqueous two-phase systems. J. Braz Chem. Soc. 21, 921–926 (2010).

Nowruzi, B. & Lorenzi, A. S. Molecular phylogeny of two Aliinostoc isolates from a paddy field. Pl Syst. Evol. 309, 11 (2023).

Shafaei Bajestani, M., Anvar, S. A. A., Nowruzi, B. & Golestan, L. Production of cheese and ice cream enriched with Biomass and Supernatant of Spirulina platensis with emphasis on Organoleptic and Nutritional properties. Iran. J. Vet. Med. 18, 263–278 (2000).

Ramadan, K. M. et al. Potential antioxidant and anticancer activities of secondary metabolites of Nostoc linckia cultivated under Zn and Cu stress conditions. Processes 9, 1972 (2021).

Ghosh, T. & Mishra, S. Studies on extraction and stability of C-phycoerythrin from a marine cyanobacterium. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 4, 561714 (2020).

García, A. B., Longo, E., Murillo, M. C. & Bermejo, R. Using a B-phycoerythrin extract as a natural colorant: application in milk-based products. Molecules 26, 297 (2021).

Nikolic, M. R., Minic, S., Macvanin, M., Stanic-Vucinic, D. & Cirkovic Velickovic, T. In Pigments from Microalgae Handbook 179–201 (Springer, 2020).

Gheda, S. F. & Ismail, G. A. Natural products from some soil cyanobacterial extracts with potent antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 92, e20190934 (2020).

Galetović, A. et al. Use of phycobiliproteins from atacama Cyanobacteria as food colorants in a dairy beverage prototype. Foods 9, 244 (2020).

Patel, P. et al. Development of a carotenoid enriched probiotic yogurt from fresh biomass of Spirulina and its characterization. JFST 56, 3721–3731 (2019).

Valikboni, S. Q., Anvar, S. A. A. & Nowruzi, B. Study of the effect of phycocyanin powder on physicochemical characteristics of probiotic acidified feta-type cheese during refrigerated storage. Nutrire 49, 41 (2024).

Pan-Utai, W., Atkonghan, J., Onsamark, T. & Imthalay, W. Effect of arthrospira microalga fortification on physicochemical properties of yogurt. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 8, 531–540 (2020).

Yilmaz-Ersan, L. & Topcuoglu, E. Evaluation of instrumental and sensory measurements using multivariate analysis in probiotic yogurt enriched with almond milk. JFST 2022, 1–11 (2022).

Hosseini, F., Motamedzadegan, A., Raeisi, S. N. & Rahaiee, S. Antioxidant activity of nanoencapsulated Chia (Salvia hispanica L.) seed extract and its application to manufacture a functional cheese. Food Sci. Nutr. 11, 1328–1341 (2023).

Shunmugiah Veluchamy, R. et al. Physicochemical characterization and fatty acid profiles of testa oils from various coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) genotypes. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 103, 370–379 (2023).

Shahryari, A., Aali, R., Zare, M. R. & Ghanbari, R. Relationship between frequency of Escherichia coli and prevalence of Salmonella and Shigella spp. in a natural river. JEHSD 2, 416–421 (2017).

Gómez, P. I. et al. Looking beyond Arthrospira: comparison of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of ten cyanobacteria strains. Algal Res. 2023, 103182 (2023).

Ulloa, P. A. et al. Effect of the addition of propolis extract on bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of craft beer. J. Chem. 2017, 859 (2017).

Guerreiro, A., Andrade, M. A., Menezes, C., Vilarinho, F. & Dias, E. Antioxidant and cytoprotective properties of cyanobacteria: potential for biotechnological applications. Toxins 12, 548 (2020).

Sarkar, P. et al. Antioxidant molecular mechanism of adenosyl homocysteinase from cyanobacteria and its wound healing process in fibroblast cells. Mol. Biol. Rep. 47, 1821–1834 (2020).

Camacho, F., Macedo, A. & Malcata, F. Potential industrial applications and commercialization of microalgae in the functional food and feed industries: a short review. Mar. Drugs 17, 312 (2019).

Beheshtipour, H., Mortazavian, A. M., Haratian, P. & Darani, K. K. Effects of Chlorella vulgaris and Arthrospira platensis addition on viability of probiotic bacteria in yogurt and its biochemical properties. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 235, 719–728 (2012).

Matos, J., Cardoso, C., Bandarra, N. M. & Afonso, C. Microalgae as healthy ingredients for functional food: a review. Food Funct. 8, 2672–2685 (2017).

Robertson, R. C. et al. An assessment of the techno-functional and sensory properties of yoghurt fortified with a lipid extract from the microalga Pavlova lutheri. IFSET 37, 237–246 (2016).

Barkallah, M. et al. Effect of Spirulina platensis fortification on physicochemical, textural, antioxidant and sensory properties of yogurt during fermentation and storage. LWT 84, 323–330 (2017).

da Silva, S. C. et al. Spray-dried Spirulina platensis as an effective ingredient to improve yogurt formulations: testing different encapsulating solutions. JFF 60, 103427 (2019).

Alizadeh Khaledabad, M., Ghasempour, Z., Moghaddas Kia, E., Rezazad Bari, M. & Zarrin, R. Probiotic yoghurt functionalised with microalgae and Zedo gum: chemical, microbiological, rheological and sensory characteristics. Int. J. Dairy. Technol. 73, 67–75 (2020).

Atallah, A. A., Morsy, O. M. & Gemiel, D. G. Characterization of functional low-fat yogurt enriched with whey protein concentrate, Ca-caseinate and spirulina. Int. J. Food Prop. 23, 1678–1691 (2020).

Bchir, B. et al. Investigation of physicochemical, nutritional, textural, and sensory properties of yoghurt fortified with fresh and dried Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis). Int. Food Res. J. 26 (2019).

Mohamed, A., Abo-El-Khair, B. & Shalaby, S. M. Quality of novel healthy processed cheese analogue enhanced with marine microalgae Chlorella vulgaris biomass. World Appl. Sci. J. 23, 914–925 (2013).

Tohamy, M. M., Ali, M. A., Shaaban, H. A. G., Mohamad, A. G. & Hasanain, A. M. Production of functional spreadable processed cheese using Chlorella vulgaris. Acta Scient. Polonorum Technol. Aliment. 17, 347–358 (2018).

Agustini, W. Application of Spirulina Platensis on ice cream and soft cheese with respect to their nutritional and sensory perspectives. Jurnal Teknol. 78, 245–251 (2016).

Bosnea, L. et al. In Proceedings. 99 (MDPI, 2024).

Mohamed, A. G., El-Salam, B. & Gafour, W. Quality characteristics of processed cheese fortified with Spirulina powder. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. PJBS 23, 533–541 (2020).

Golmakani, M. T., Soleimanian-Zad, S., Alavi, N., Nazari, E. & Eskandari, M. H. Effect of Spirulina (Arthrospira platensis) powder on probiotic bacteriologically acidified feta-type cheese. J. Appl. Phycol. 31, 1085–1094 (2019).

Darwish, A. M. I. Physicochemical properties, bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of Kareish cheese fortified with Spirulina platensis. WJDFS 12, 71–78 (2017).

Nowruzi, B. & Porzani, S. J. Study of temperature and food-grade preservatives affecting the in vitro stability of phycocyanin and phycoerythrin extracted from two Nostoc strains. Acta Biol. Slov. 65, 28–47 (2022).

Ju, J. et al. Neurotoxic evaluation of two organobromine model compounds and natural AOBr-containing surface water samples by a Caenorhabditis elegans test. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 104, 194–201 (2014).

Hamed, I. et al. Encapsulation of microalgal-based carotenoids: recent advances in stability and food applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. (2023).

Sun, H. et al. Microalgae-derived pigments for the food industry. Mar. Drugs 21, 82 (2023).

Tavakoli, S. et al. Recent advances in the application of microalgae and its derivatives for preservation, quality improvement, and shelf-life extension of seafood. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 6055–6068 (2022).

MU, N., Mehar, J. G., Mudliar, S. N. & Shekh, A. Y. Recent advances in microalgal bioactives for food, feed, and healthcare products: commercial potential, market space, and sustainability. CRFSFS 18, 1882–1897 (2019).

Shin, D. H. & Rawls, H. R. Degree of conversion and color stability of the light curing resin with new photoinitiator systems. Dent. Mater. J. 25, 1030–1038 (2009).

Nowruzi, B., Fahimi, H. & Lorenzi, A. S. Anales De Biología 115–128 (Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia, 2024).

Terzioğlu, M. E., Edebali, E. & Bakirci, I. Investigation of the elemental contents, Functional and Nutraceutical Properties of Kefirs Enriched with Spirulina platensis, an eco-friendly and alternative protein source. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 202, 2878–2890 (2024).

Liu, Z. W., Manzoor, M. F., Tan, Y. C., Inam-ur‐Raheem, M. & Aadil, R. M. Effect of dielectric barrier discharge (DBD) plasma on the structure and antioxidant activity of bovine serum albumin (BSA). IJFST 55, 2824–2831 (2020).

Ionita, P. The chemistry of DPPH· free radical and congeners. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1545 (2021).

Adegbaju, O., Otunola, G. & Afolayan, A. Effects of growth stage and seasons on the phytochemical content and antioxidant activities of crude extracts of Celosia argentea L. Heliyon 2020, 6 (2020).

Benzie, I. F. & Devaki, M. The ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) assay for non-enzymatic antioxidant capacity: concepts, procedures, limitations and applications. Meas. Antioxid. Activity Capacity: Recent. Trends Appl. 2018, 77–106 (2018).

Noori, A., Keshavarzian, F., Mahmoudi, S., Yousefi, M. & Nateghi, L. Comparison of traditional Doogh (yogurt drinking) and Kashk characteristics (two traditional Iranian dairy products). Eur. J. Exp. Biol. 3, 252–255 (2013).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, B.N and S.A.A.; methodology, S.A.A and A.A.; software, B.N.; validation, B.N, S.A.A, N.B and L.G; formal analysis, B.N and N.B.; investigation, S.A.A and L.G.; resources, B.N. and S.A.A; data curation., B.N and S.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.N.; writing—review and editing, S.A.A and B.N.; visualization, B.N.; supervision, A.A; project administration, S.A.A; funding acquisition, S.A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript All Authors confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations. The authors did not do any experiments on humans and/or the use of human tissue samples. All experimental protocols and panelists involved in the study were approved by the ethics committee of Tehran Medical Sciences, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. Participants gave their consent to take part and use their information. The full name of the ethics committee that approved the study is Dr Fahimeh Nemati and Dr Sarvenaz Falsafi.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article Leila Golestan was incorrectly affiliated with ‘Department of Food Science and Technology, Faculty of Agriculture and Food Science Ayatollah Amoli Branch, Islamic Azad University, Amol, Iran’. The correct affiliation is listed here: Department of food hygiene, Ayatollah Amoli Branch, Azad University, Amol, Iran.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmadi, A., Anvar, S.A.A., Nowruzi, B. et al. Effect of phycocyanin and phycoerythrin on antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of refrigerated low-fat yogurt and cream cheese. Sci Rep 14, 27661 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79375-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79375-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Comparative analysis of two Porphyridium species for phycobiliprotein and polysaccharide production under different photoperiods

Bioresources and Bioprocessing (2025)