Abstract

This study aimed to describe a novel sandwich technique of minimally invasive surgical implantation by using corneal stromal lenticules for corneal perforation. This prospective observational study included nine patients aged 23–79 years (mean, 54 ± 9) from Tianjin Eye Hospital. Corneal stromal lenticules with a central thickness of 120 μm were obtained from small incision lenticule extraction(SMILE). With the corneal perforation as the central point, an iris-repositor was used to manually create a mid-stromal pocket; the stromal lenticular button was gently inserted into the intrastromal pocket and flattened. The graft was sandwiched between the anterior and posterior corneal stromal pockets; the incision was closed using two sutures. The primary health outcome measured in this study was the logMAR best spectacle-visual acuity at 6 months postoperatively. Corneal perforation closure and anterior chamber formation occurred immediately after surgery. No epithelial implantation, infection, or allogeneic rejection was observed during the follow-up. No patients required a penetrating keratoplasty. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography revealed a mean thickness of the grafted tissue of 122 ± 21 μm, with a clear interface in all cases. Comparing the baseline and postoperative 6-month values, the mean logMAR best spectacle-corrected visual acuity was improved from 0.18 ± 0.12 to 0.52 ± 0.31 (P < 0.001). There was significant reduction in the mean manifest spherical equivalent, refractive cylinder, and mean keratometry readings. The novel minimally invasive surgical method for corneal implantation. It was an effective alternative treatment that could restore corneal integrity and improve vision in patients with corneal perforations. This method appears safe, easy, cost- and time-effective, and reliable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corneal perforations require urgent attention and prompt treatment because this condition, which can occur as a result of numerous other conditions, is a potentially devastating complication that can precipitate corneal melting and even cause blindness1,2. The difficulty in therapeutic methods for corneal perforations could cause complications, including epithelial ingrowth, interface scarring, and induced astigmatism3,4,5. Moreover, corneal perforation may be more challenging to rectify depending on the eye condition and the presence of rheumatism, graft-versus-host diseases (GVHD), or severe dry eye6,7.

Previous studies have used adhesive, penetrating keratoplasty, contact lenses, and conjunctival flaps to treat corneal perforations. However, most of these methods have limitations, such as the potential immune response in the anterior chamber and the risk of secondary infection and endophthalmitis8,9. Therefore, alternative techniques, ideally with easy handling and low cost, are required to improve clinical outcomes in patients with corneal perforation. Thus, we developed a novel procedure, the “sandwich technique of minimally invasive implantation”, which involves implanting the corneal lenticule into the allogeneic corneal stroma through a small incision. In this prospective case series, we describe this technique and present our initial experience and clinical outcomes six months post-intervention.

Materials and methods

This prospective observational study enrolled patients from Tianjin Eye Hospital between March 2020 and October 2023. Informed consent was obtained from all patients undergoing the procedure after explaining the nature and risks associated with the surgery in lay language they understood. This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki, approved by the ethics committee of Tianjin Eye Hospital (No. KY2023070), and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT06233409).

Lenticules were obtained from healthy donors aged 19–22 who were scheduled to undergo refractive small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) surgery for myopia (myopic spherical refractive error ranging between − 6.0 D and − 6.5 D). All lenticules were collected on the same day and immediately frozen for storage. Formal informed consent was obtained from all donors for using their tissues in a new procedure. Serological tests were conducted in participants who consented to donate their lenticules to avoid transmission of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis C virus, and syphilis. Preoperatively, all patients underwent a slit-lamp examination and measurement of uncorrected visual acuity and corrected distance visual acuity using standard logMAR and Snellen tests. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography (AS-OCT, Optovue, Fremont, CA, and Visante OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, USA) was performed to document the corneal thickness of the recipient and guide the calculation of the 120 μm lenticule thickness needed.

Nine eyes of nine patients (five male and four female) aged 23–79 years who required a donor’s graft were selected. Only patients with peripheral corneal perforations measuring 3.5 mm or less in diameter were eligible for inclusion in the study. This size limit was chosen to ensure that the lenticule could adequately cover the perforation while maintaining corneal integrity. The study excluded cases with bacterial or fungal infections, exposure keratitis, or signs of intraocular infection, as these conditions posed a higher risk of complications that could adversely affect the surgical outcomes. Additionally, no other surgical approaches (e.g., glueing) were used prior to the surgery for any of the patients. The preoperative details of all patients, including demographics, visual acuity, indication for surgery, and extent of corneal thickness on AS-OCT, are presented in Table 1.

Preparation of corneal stromal lenticules

The surgery procedure was planned after ensuring the availability of corneal stromal lenticules from donors scheduled for femtolaser SMILE by the same surgeon (YW). A 500-kHz VisuMax femtosecond laser (Carl Zeiss, Meditec AG, Oberkochen, Germany) was used for the lenticule creation in the donor cornea for the correction of myopia, with a refractive error ranging between − 6.0 D and − 6.5 D. The protocol included a cap thickness of 110 μm, an optical zone diameter of 6.0 mm, and a lenticule central thickness of 120 μm. The fresh lenticule tissue was immediately transferred into sterile frozen tubes containing phosphate buffer solution under strictly aseptic conditions and stored at -80 °C for up to 3 months before surgery.

Surgical design and technique

All surgeries were performed by the same surgeon (LXC). Under topical anesthesia, 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride eye drops were administered. Briefly, Gentian violet and a corneal trephine were used to mark a 6.25 mm diameter ring centered on the corneal perforation area. A 3.0 mm incision was made at the most ergonomic angle for the surgeon, rather than always in the temporal position, to facilitate easier subsequent steps. The incision depth was set to approximately 150 μm within the corneal stroma.

To create the incision, a single-use 15° knife (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) was used to carefully score along the marked area to a depth of 100–200 μm. Care was taken to avoid excessive pressure that could compromise the incision. When forming the intrastromal pocket (6.25 mm diameter), extreme caution was exercised to avoid tearing the pouch opening, which could lead to unnecessary sutures or compromised surgical outcomes.

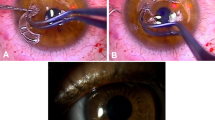

The donor corneal stromal lenticules were trimmed into 6.0 mm lenticules using a corneal trephine. Before cutting, the trephine’s blade was coated with a marking dye to ensure that the edges of the lenticule were clearly marked post-cutting, allowing easy identification and proper positioning of the lenticule during the procedure. The marked lenticule was curled and gently inserted into the recipient’s corneal stroma through the 3.0 mm incision. The placement was meticulously adjusted using an iris restorer to ensure that the edge markings were fully visible, confirming proper positioning. This technique was demonstrated in the intraoperative video of lenticule intrastromal transplantation (Video 1 and Fig. 1). The iris tissue was gently restored during the procedure, and any iris-corneal adhesions were left untreated unless necessary. Finally, the incision was closed with or without sutures, and the surgical area was covered with a bandage contact lens. Postoperative follow-ups were conducted for 6 months in all cases.

Diagram showing the dissection and insertion of the cornea during the sandwich method. (a) The cornea graft with a 120 mm thickness is made and dissected using the corneal lenticules obtained from the small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) donor. (b) A corneal lamellar separator creates the intrastromal pocket on the receptor cornea perforation area. (c) The dissected donor cornea is rolled and inserted into the intrastromal pocket. (d) The graft is ironed out and adjusted until it covers the center of the perforation region.

Postoperative medications

Postoperatively, fluorometholone 0.1% eye drops (Santen, Osaka, Japan) were administered three times daily for 1 month and then replaced with 0.02% fluorometholone eye drops (Santen), tapered within 12 months. Levofloxacin 0.5% eye drops (Santen, Osaka, Japan) were administered four times daily for 1 week. Tacrolimus eye drops were administered twice daily for 2 months, 2 weeks after surgery.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS for Windows software, version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). Statistics are presented as mean and standard deviation. The paired-sample t-test and analysis of variance were used to compare the parameters at different examination time points. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The recipient patients were four females and five males, averaging 54.5 ± 9 years (range: 23–79 years). Six patients had corneal perforations in the right eye and three patients in the left. In this study, the most common cause of corneal perforation was immunological (77.78%). In six cases, corneal perforation was secondary to rheumatoid arthritis and GVHD (three due to severe dry eye). In one patient, corneal perforation was caused by herpes simplex keratitis, whereas another patient had corneal perforation due to ferruginous foreign body trauma. Table 1 summarizes patient demographics and surgical outcomes.

Slit-lamp examination

All patients tolerated the procedure well and showed normal intraocular pressure (IOP; range, 12–19 mmHg) at 1–6 months postoperatively. Slit-lamp examination revealed mild or moderate corneal edema on the first day postoperatively, which improved within 5 days. All patients exhibited anterior chamber formation. One patient experienced intraocular hypertension (29 mmHg) due to topical corticosteroid administration at 3 months postoperatively and was treated with 2% Timolol (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.) and tacrolimus eye drops instead of 0.1% fluorometholone eye drops. Subsequently, the patient’s IOP was successfully controlled within 2 weeks. No epithelial mismigration, infection, or signs of allogeneic rejection were observed in any of the treated eyes during follow-up (Fig. 2).

Pre- and postoperative corneal conditions in a patient with a corneal ulcer (Patient 2).The images represent the corneal conditions before and after surgery at different time points. (a, b, c) show the preoperative state, (d, e, f) represent 1 week postoperatively, and (g, h, i) illustrate the condition at 1 month postoperatively. Images (a, d, g) are taken under diffused light, (b, e, h) are slit-lamp images, and (c, f, i) are anterior segment OCT scans. (a, b) display the preoperative corneal ulcer condition. (d, e) show significant healing of the ulcer 1 week postoperatively. (g, h) depict the corneal edema resolution at 1 month postoperatively. (c, f, i) illustrate the OCT scans at the corresponding time points, showing the gradual restoration of the corneal structure.

Vision and refractive errors

Six months postoperatively, the mean best-corrected visual acuity (logMAR) improved from 0.18 ± 0.12 to 0.52 ± 0.31 (P < 0.001). No patients required a penetrating keratoplasty. Two eyes gained five lines, one eye gained seven lines, three gained four lines, one gained one line, and one gained 0.05. (Fig. 3). Comparing the baseline and postoperative 6-month values, the mean logMAR uncorrected and best-spectacle-corrected visual acuities improved from 0.18 ± 0.12 to 0.52 ± 0.31 (P < 0.001).

Furthermore, we observed a significant reduction in the mean manifest spherical equivalent, refractive cylinder, and mean keratometry readings (P values).

Discussion

Reusing human corneal stromal lenticules provides a new approach to treating corneal diseases10,11,12. In this study, we describe and present our initial experience and clinical outcomes 6 months post-intervention using the novel method for treating corneal perforation and observed several key findings. First, we found that the morphological structure of the lenticular graft was more suitable for implantation as the single-piece SMILE lenticule was thick in the center, gradually thinning around the periphery, and had a thin edge. In contrast, the perforated area was thin in the center and thick at the periphery. Thus, the graft and recipient had complementary morphologies that fit together seamlessly. Second, the thickness of the implanted graft was approximately 120 mm, thereby ensuring that the integrity of the cornea could be restored while maintaining a relatively minimal effect on refraction. Therefore, interlamellar implantation was more appropriate for corneal perforations secondary to rheumatoid arthritis, severe dry eye, or GVHD. Our results suggest that the lenticular material intrastromal implantation was a safe and feasible means of reversing corneal perforation.

Several procedures, such as tissue adhesives, tenon patch grafting, conjunctival flaps, and amniotic membrane transplantation, have been described for treating corneal perforations. However, these treatments increase the risk of cyanoacrylate toxicity, tenon patch scarring, and corneal vascularization, resulting in hypotony and predisposing the eye to endophthalmitis4,13,14. These complications were avoided in the present study, minimizing damage, particularly in patients with iris-corneal adhesions. The minimally invasive surgical method employed herein did not disturb the iris or alter the eye microenvironment1.

With the widespread clinical application of SMILE surgery, many lenticules have been produced, and nearly 100,000 stromal lenticules are obtained annually in China. Therefore, the reuse and preservation of stromal lenses have become a research hotspot for ophthalmologists15,16. Corneal stromal lenticules are used to treat corneal ulcers differently. One way is to use single-piece corneal stromal lenticules to repair the perforation by suturing, and the other is to use multilayer SMILE lenticules to cover the perforation by gluing. However, these techniques may cause an increased risk of nonadherence of the grafted tissue to the cornea, and an uneven thickness cannot be maintained17,18. Therefore, new techniques necessitate various modifications to the original surgical technique to achieve better clinical outcomes, such as rapid restoration of the complete structure of the cornea, immediate formation of the anterior chamber, and fewer complications.

In contrast, tectonic mini-Descemet stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (mini-DSAEK) has been shown to be an effective technique for closing corneal perforations in patients with healthy endothelium19,20. This method requires fresh donor corneal material and is technically more demanding, with the risk of graft dislocation postoperatively. While mini-DSAEK has demonstrated rapid visual recovery and minimal postoperative astigmatism, its dependence on donor tissue availability and the complexity of the procedure limit its widespread application. Additionally, graft detachment is a potential complication that necessitates careful postoperative management21. In contrast, the reuse of SMILE lenticules offers a cost-effective, readily available, and less invasive alternative, particularly in regions where access to fresh donor corneas is limited.

Another advantage of this technology is that the transplanted lenticules could be preserved for an extended time (at least 3 months at -80 ˚ C). Owing to global issues such as coronavirus disease 201922,23, corneal sources in eye banks in the United States, Brazil, India, and Italy is scarce. Fresh corneas can only be preserved for 2 (4 °refrigeration) or 4 weeks (corneal preservation solution), resulting in a 10–50% disposal rate24,25,26,27. The scarcity and inability to preserve corneal sources for a long time pose a considerable challenge to clinicians. In this study, each lenticule was preserved for at least 3 months, which resolves the shortcomings of previous efforts to preserve donor corneas for long durations.

In the present study, we performed the surgery utilizing corneal stromal lenticules to manage corneal perforations. Here, we describe a “sandwich” maneuver, which has become our standard strategy for eyes with corneal perforation. Postoperative visual acuity improved in central and peripheral perforations (Fig. 4). This maneuver requires no additional or specialized instrumentation and uses only manipulations that an average keratoplasty surgeon will likely be familiar with. The minimally invasive surgical method was successfully performed in all nine perforated corneas with minimal intraoperative complications; it was implanted into a region located around half of the corneal thickness without disrupting the posterior corneal stromal tissue or iris. Therefore, this technique is safe, with limited post-surgical inflammation reported. The urgent nature of corneal perforations necessitates immediate repair. Although treating corneal perforation caused by some immune-related diseases remains challenging, our technique is specifically suitable for autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca, Sjogren’s syndrome, and Mooren’s ulcer corneal perforation.

Tectonic keratoplasty procedure. (a) Stromal pockets with a diameter of 6 mm are made in the corneal perforation area, and the same size lenticule graft is prepared. (b) The whole lenticule is implanted into the stromal pocket and centered around the corneal perforation area. This procedure is similar to the sandwich method. (c) Sutured (or not sutured) using interrupted 10 − 0 nylon and ironed out with an iris repositor.

Notably, our patients received stromal lenticules without additional financial costs. The scarcity of corneal tissue to treat corneal perforations in China remains challenging, and corneal perforations increasingly cause blindness owing to the lack of necessary corneal tissue availability. Finally, we anticipate that surgeons could adopt the sandwich intrastromal procedure as a more straightforward, safer, and less invasive option for corneal perforation than the standard deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty or penetrating keratoplasty, even with donor corneas. Corneal stromal lenticules offer advantages such as good biocompatibility, ease of operation, and low cost. When the supply of corneal tissue is far from the demand, corneal stromal lenticules may be a viable substitute in some instances.

This study has some limitations. First, the number of cases in this study was relatively small. However, we provided clinicians with a novel technique for treating corneal perforation. Second, the follow-up time in the patients was relatively short; we are currently conducting longer follow-up observations in such patients. Third, the technique was only applied to peripheral perforations, which limits the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

We developed a novel sandwich technique for minimally invasive keratoplasty to treat corneal perforations. Corneal stromal lenticules obtained through femtosecond laser small-incision lenticule extraction were inserted into the intrastromal pocket to successfully treat nine eyes with corneal perforations. Our results suggest that this technique was safe and effective and provided an option to restore corneal integrity and improve vision in patients with micro-perforations, while also providing an extended period to preserve necessary donor tissue.

Data availability

The dataset used and analyzed in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Al Saleh, A., Al Saleh, A. S., Al, A. & Qahtani Recurrent and refractory corneal perforation secondary to rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 34, 216–217. https://doi.org/10.4103/1319-4534.310409 (2020).

Jhanji, V. et al. Management of corneal perforation. Surv. Ophthalmol. 56, 522–538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.06.003 (2011).

Rodríguez-Ares, M. T., Touriño, R., López-Valladares, M. J. & Gude, F. Multilayer amniotic membrane transplantation in the treatment of corneal perforations. Cornea. 23, 577–583. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ico.0000121709.58571.12 (2004).

Bhandari, V., Ganesh, S., Brar, S. & Pandey, R. Application of the SMILE-derived glued lenticule patch graft in microperforations and partial-thickness corneal defects. Cornea. 35, 408–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000000741 (2016).

Abd Elaziz, M. S., Zaky, A. G., El, A. R. & SaebaySarhan Stromal lenticule transplantation for management of corneal perforations; one year results, Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 255, 1179–1184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00417-017-3645-6 (2017).

Lekskul, M., Fracht, H. U., Cohen, E. J., Rapuano, C. J. & Laibson, P. R. Nontraumatic corneal perforation. Cornea. 19, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003226-200005000-00011 (2000).

Xu, Y. et al. Corneal perforation associated with ocular graft-versus-host disease. Front. Oncol. 12, 962250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.962250 (2022).

Rana, M. & Savant, V. A brief review of techniques used to seal corneal perforation using cyanoacrylate tissue adhesive, Cont. Lens Anterior Eye. 36, 156–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clae.2013.03.006 (2013).

Sharma, A., Mohan, K. & Nirankari, V. S. Management of nontraumatic corneal perforation with tectonic drape patch and cyanoacrylate glue, cornea 31/4 465–6; author reply 466. (2012). https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0b013e31821de358

Zhang, H., Deng, Y., Li, Z. & Tang, J. Update of research progress on small incision lenticule extraction (SMILE) lenticule reuse. Clin. Ophthalmol. 17, 1423–1431. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S409014 (2023).

Jiang, Y., Li, Y., Liu, X. W. & Xu, J. A novel tectonic keratoplasty with femtosecond laser intrastromal lenticule for corneal ulcer and perforation. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 129, 1817–1821. https://doi.org/10.4103/0366-6999.186639 (2016).

Mastropasqua, L., Nubile, M., Salgari, N. & Mastropasqua, R. Femtosecond laser-assisted stromal lenticule addition keratoplasty for the treatment of advanced keratoconus: a preliminary study. J. Refract. Surg. 34, 36–44. https://doi.org/10.3928/1081597X-20171004-04 (2018).

Sharma, A., Sharma, R. & Nirankari, V. S. Intracorneal scleral patch supported cyanoacrylate application for corneal perforations secondary to rheumatoid arthritis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69/1, 69–73. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2258_19 (2021).

Chan, E. & Ayres, M. Corneal perforation with iris plugging. JAMA Ophthalmol. 136, e180081. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.0081 (2018).

Pant, O. P., Hao, J. L., Zhou, D. D., Pant, M. & Lu, C. W. Tectonic keratoplasty using small incision lenticule extraction-extracted intrastromal lenticule for corneal lesions. J. Int. Med. Res. 48, 300060519897668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060519897668 (2020).

Ganesh, S. & Brar, S. Femtosecond intrastromal lenticular implantation combined with accelerated collagen cross-linking for the treatment of keratoconus–initial clinical result in 6 eyes. Cornea. 34, 1331–1339. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000000539 (2015).

He, N., Song, W. & Gao, Y. Treatment of Mooren’s ulcer coexisting with a pterygium using an intrastromal lenticule obtained from small-incision lenticule extraction: case report and literature review. J. Int. Med. Res. 49, 3000605211020246. https://doi.org/10.1177/03000605211020246 (2021).

Liu, J. L. et al. Treatment of corneal dermoid with lenticules from small incision lenticule extraction surgery: a surgery assisted by fibrin glue. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 16, 547–553. https://doi.org/10.18240/ijo.2023.04.08 (2023).

Seifelnasr, M., Roberts, H. W., Moledina, M. & Myerscough, J. Tectonic Mini-DSAEK facilitates Closure of corneal perforation in eyes with healthy endothelium. Cornea. 40, 790–793. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000002712 (2021).

Vasquez-Perez, A., Din, N., Phylactou, M., Kriman Nunez, J. & Allan, B. Mini-DSAEK for macro corneal perforations. Cornea. 40, 1079–1084. https://doi.org/10.1097/ICO.0000000000002713 (2021).

Roberts, H. W. et al. Sutureless Tectonic Mini-descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (mini-DSAEK) for the management of corneal perforations. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32, 2133–2140. https://doi.org/10.1177/11206721211050034 (2022).

Busin, M., Yu, A. C. & Ponzin, D. Coping with COVID-19: an Italian perspective on corneal surgery and eye banking in the time of a pandemic and beyond. Ophthalmology. 127, e68–e69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.04.031 (2020).

Parekh, M. et al. Impact of COVID-19 on corneal donation and distribution. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32, NP269–NP270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672120948746 (2022).

Mencucci, R. et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on corneal transplantation: a report from the Italian association of eye banks. Front. Med. (Lausanne). 9, 844601. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.844601 (2022).

Wykrota, A. A. et al. Approval rates for corneal donation and the origin of donor tissue for transplantation at a university-based tertiary referral center with corneal subspecialization hosting a LIONS Eye Bank. BMC Ophthalmol. 22/1, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-022-02248-7 (2022).

Arya, S. K., Raj, A., Deswal, J., Kohli, P. & Rai, R. Donor demographics and factors affecting corneal utilisation in Eye Bank of North India. Int. Ophthalmol. 41, 1773–1781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-021-01736-x (2021).

Victer, T. N. et al. Causes of death and discard of donated corneal tissues: Federal District eye bank analysis 2014–2017. Rev. Bras. Ophthalmol. 78, 227–232. https://doi.org/10.5935/0034-7280.20190133[A1] (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all participants in this study and Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the following grants: Optometry Academy Open Fundation of Nankai University (2024430HJ0386), Projects of Tianjin Eye Hospital (YKZD 2002), Bethune Dry Eye Treatment and Research Project (GY2021019J), National Nature Science Foundation of China (32101101), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82271118), National Program on Key Research Project of China (2022YFC2404502), Tianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project(TJYXZDXK-016A), Tianjin Diversified Investment Fund for Applied Basic Research (21JCZDJC01190). The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. and Y.D. organized the database. L.C., Y.D., L.J., B.X., J.C., X.Y., Y.H., and Y.W. performed the analysis and interpretation of data. L.C. wrote the first draft. L.C., Y.D., L.J., B.X., J.C., X.Y., Y.H., and Y.W. commented on previous versions of the manuscript. L.C. and Y.W. provided administrative, technical, or material support, as well as supervision. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Dong, Y., Jiang, L. et al. A novel sandwich technique of minimally invasive surgery for corneal perforation. Sci Rep 14, 27675 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79376-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79376-1