Abstract

External ventricular drain (EVD) placement is often associated with complications; however, predictors of adverse outcomes after EVD placement are not well understood. This study aimed to identify predictors of EVD tract hemorrhage and to compare post-EVD hemorrhage rates between computer-assisted navigation and freehand technique EVD placement. This retrospective study included 147 consecutive patients who presented with increased intracranial pressure (ICP) requiring an EVD. Multivariable logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between predictors and adverse outcomes after EVD placement. The most common presenting pathologies in patients who had EVD placement were intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH) (43%) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) (28%). 14% of patients experienced EVD tract hemorrhage. Patients with platelet counts < 120 × 10³/µL (OR = 4.47, 95% CI = 1.01-20, p = 0.038), white blood cell counts < 11 × 10³/µL (OR = 3.3, 95% CI = 1.01–10.7, p = 0.048), and IPH (OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.06–10.7, p = 0.048) had increased risks of tract hemorrhage. The use of computer-assisted navigation did not reduce the risk of tract hemorrhage after EVD placement compared to the freehand technique. This study identified factors associated with increased risks of hemorrhage after EVD placement, which can help triage at-risk patients and reduce adverse outcomes of this procedure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

External ventricular drains (EVDs) relieve intracranial pressure (ICP) by draining cerebrospinal fluid in patients with serious neurological conditions, such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), hydrocephalus, and intracranial neoplasms1. In the United States, approximately 25,000 EVD procedures are performed annually, making it one of the most common neurosurgical procedures2.

EVD placement can result in significant complications, such as hemorrhage, infection, and misplacement. To improve the precision of EVD placement and reduce the risk of complications, new techniques and technologies have been developed. For example, computer-assisted navigation systems enable neurosurgeons to navigate the catheter more precisely into the ventricle, reducing the number of punctures and the risk of misplacement1. Despite these advancements, complications resulting from EVD placement continue to be a significant problem. Tract hemorrhage, in particular, is a common and potentially life-threatening complication that occurs in up to 7% of cases2. The factors that contribute to increased risk of post-EVD placement tract hemorrhage are not well understood. Whether the use of a computer-assisted navigation system reduces EVD complications is also uncertain.

This study aims to identify predictors of tract hemorrhage after EVD placement, and to compare the incidence of this complication between procedures using a computer-assisted navigation system and those using freehand placement. By identifying factors that contribute to these complications and evaluating the effectiveness of computer-assisted navigation, the safety and outcomes of EVD placement can be improved.

Methods

Experimental design

This retrospective study included 147 consecutive patients aged > 18 years who presented with both neurological and radiographic signs of increased ICP requiring an EVD at Methodist Dallas Medical Center between 2018 and 2022. Institutional review board approval was obtained as an exempt study, and the need to obtain informed consents was waived (Methodist Health System Institutional Review Board, Dallas, TX; Protocol # 102.MBSI.2022.D, approved 09-19‐2022). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population were obtained by reviewing electronic medical records. Variables collected included age, body mass index (BMI), race/ethnicity, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, cerebral vascular disease, and others), use of antithrombic drugs (e.g., oral anticoagulants or antiplatelet agents) before intervention, the etiopathogenesis of increased ICP (e.g., IPH, SAH, TBI, brain tumors, hydrocephalus, or infection), setting of EVD placement (i.e., operating room versus neuro-critical care unit [NCCU]), and side of EVD placement (i.e., left or right). The use of computer-assisted navigation was at the neurosurgeons’ discretion. Additional variables included Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, opening ICP measured at the time of EVD puncture, number of days with the EVD, length of hospital stay, EVD complications, and 30-day operative mortality, defined as any death in or out of the hospital.

EVD insertion and neuro-navigation system procedures

The classic EVD insertion technique through Kocher’s point and the use of computer-assisted navigation (AxiEM Stealth system®) for EVD insertion have been described elsewhere1. The AxiEM Stealth system enhances the accuracy of EVD placement by allowing surgeons to visualize the exact position of the catheter during insertion, reducing the risk of complications and improving outcomes. This system uses electromagnetic tracking to provide real-time, precise localization of surgical instruments relative to the patient’s anatomy. Accuracy of EVD placement was evaluated using Kakarla’s grading system, which is described elsewhere3.

Tract hemorrhage evaluation after EVD placement

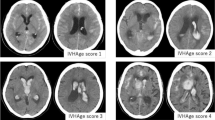

The EVD tract hemorrhage grading scale was used to evaluate the incidence of tract hemorrhage in serial computed tomography scans taken after the procedure4. The scale consists of four grades: grade 0, no tract hemorrhage; grade 1, trace amount of tract hemorrhage; grade 2, tract hemorrhage with moderate intracerebral hematoma without mass effect; and grade 3, large tract hemorrhage with mass effect (Fig. 1). Tract hemorrhage was analyzed as a binary variable, with patients being classified as either having or not having tract hemorrhage.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System OnDemand for Academics (SAS Institute, Cary, NC; RRID: SCR_008567) and data visualization was conducted using PythonXY 3.9 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE; RRID: SCR_006903). Basic descriptive statistics were used to analyze the distribution of continuous variables. These were described as means with standard deviation (SD) or medians with minimum and maximum values if the distribution was non-normal. Categorical variables were described with frequencies and percentages. A t-test or Wilcoxon rank test was used to determine any differences between continuous variables, and a chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. Logistic regression was used to test the association between individual predictors and EVD tract hemorrhage. For this analysis, the cutoff value for continuous predictors associated with the outcome was established. The optimal cutoff value that maximized the OR was selected, indicating the strongest association between the test result and the presence of tract hemorrhage. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to establish the relationship between predictors and tract hemorrhage secondary to EVD placement. A significance level of p < 0.2 in the unadjusted analysis was used as a cutoff value to include a variable in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, following manual backward variable selection. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and the odds ratios were described with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

In total, 147 patients presented with both neurological and radiographic signs of increased ICP requiring an EVD. The mean (SD) age of the patients was 54.2 (14.2) years (Table 1). A greater proportion of women (52%) than men (48%) had an EVD placement. Additionally, 46% of patients who required an EVD placement were non-Hispanic Blacks. The most common reasons for EVD placement were IPH (43%) and SAH (28%). Less frequently encountered were cases of hydrocephalus (7%): two were idiopathic, while the others were sequelae of infections. Among the IPH cases, 59% were in the supratentorial region. EVD placement was most often (71%) performed in the NCCU setting and computer-assisted navigation was used in 18% of the cases. The EVDs were optimally placed in 99% of the patients and in the contralateral ventricle in 1%. 22% of the patients were on anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

14% of EVDs placed had tract hemorrhage. Of these, 6%, 4%, and 3% had grade 1, 2, or 3 tract hemorrhage, respectively. EVD tract hemorrhage was most common among patients with IPH (65%). Patients with EVD tract hemorrhage had lower median (min-max) white blood cell (WBC) counts (8.7 (1-22.5) x 103 /µL vs. 11 (2.9–24) x 103 /µL, p = 0.002) and lower mean (SD) platelet levels (207 (88) x 103 /µL vs. 263 (92) x 103 /µL, p = 0.01) than patients without tract hemorrhage (Table 1). Although the operative mortality rate was 23%, defined as any death within 30 days after surgery regardless of cause, EVD tract hemorrhage was not a significant risk factor (p = 0.8). This includes deaths occurring in or out of the hospital.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationship between various factors and the risk of EVD tract hemorrhage (Table 2). To improve the power of the sample, the different causes of ICP elevation was dichotomized into patients with IPH and patients with other etiologies of ICP elevation. Patients with IPH had an increased risk of EVD tract hemorrhage compared with other pathologies (OR = 2.7, 95%CI = 1.03–7.4, p = 0.043). To enhance the interpretability of predictors such as platelets and WBC, these variables were dichotomized according to their cutoff values. Platelet counts < 120 × 10³/µL (OR = 5.0, 95%CI = 1.3–20.0, p = 0.02) and WBC counts < 11 × 103/ µL (OR = 3.7, 95%CI = 1.2–11.7, p = 0.03) increased the risk of tract hemorrhage. After adjustment using a multivariate logistic model, platelet counts < 120 × 10³/µL (OR = 4.47, 95% CI = 1.01-20, p = 0.048), WBC counts < 11 × 10³/µL (OR = 3.3, 95% CI = 1.01–10.7, p = 0.048), and IPH (OR = 2.97, 95% CI = 1.06–10.7, p = 0.048) remained factors that increased the risk of tract hemorrhage (Table 3). As an example, the interpretation of the OR for platelets is as follows: having platelets < 120 × 10³/µL increases the probability of tract hemorrhage after EVD placement by 4.47 times, after adjusting for other covariates.

Surprisingly, the use of computer-assisted navigation did not reduce the risk of tract hemorrhage after EVD placement compared to the freehand technique (OR = 1.25, 95%CI = 0.3–4.6, p = 0.74).

Discussion

This study suggests that lower platelets, lower WBC counts, and IPH are risk factors for EVD tract hemorrhage. As expected, mortality following EVD placement is primarily associated with the clinical presentation of the patient, rather than the procedure itself.

In this study, 14% of EVDs placed were complicated with tract hemorrhage. This falls within the range of reported rates in the literature (1.5–41%)5. Sussman et al. (2014) found that advanced age was a predictor of EVD-related hemorrhage in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage6. We did not observe this relationship in our study, which may be due to our small sample size. In a meta-analysis examining hemorrhagic complications from ventriculostomy placement by neurosurgeons, Bauer et al. (2011a) found an overall hemorrhagic complication rate of approximately 7% and a rate of significant hemorrhage (Grade 3) of 0.8%2. Our study revealed an overall tract hemorrhage rate of 14%, with 3% having significant hemorrhage (Grade 3). Bauer et al. (2011b) also investigated the relationship between INR and tract hemorrhage after EVD placement7. They found that INRs between 1.2 and 1.6 were acceptable for placement of an emergent ventriculostomy in patients with TBIs. Consistent with these recommendations, the INR values in the current study fell within this range.

Similar to our study, Miller et al. (2017) found that decreased platelet counts at admission was associated with an increased risk of tract hemorrhage8. However, the study did not establish a platelet cutoff value associated with EVD tract hemorrhage, whereas ours did.

Increased WBC counts were protective against EVD tract hemorrhage in our study. Morotti et al. (2016) similarly observed that a higher WBC count on admission was associated with a lower risk of ICH expansion9. These findings suggest that an inflammatory response may play a role in modulating the coagulation cascade after acute hemorrhage. Besides their known roles in inflammation and fighting infections, neutrophils also contribute to various physiological processes, particularly in promoting blood clotting. Activated neutrophils enhance coagulation by expressing and releasing tissue factor, increasing active tissue factor levels, and forming extracellular traps that activate platelets and clotting factors. This procoagulant activity may help limit hematoma expansion during the early stages of ICH9.

In our study, the use of computer navigation did not reduce the risk of tract hemorrhage after EVD placement compared with the freehand approach. However, due to the small sample size, conclusions about the advantages of the computer-assisted navigation versus the freehand technique cannot be drawn. A study on bedside external ventricular placement, multiple passes, and the incidence of hemorrhage found no correlation between the number of EVD attempts and tract hemorrhage. However, that study had a sample size limitation, which makes any conclusion limited10. Attempts were not recorded in the current study; therefore, a relationship between EVD attempts, navigation, and tract hemorrhage could not be assessed. The current literature on this topic is limited, with only one ongoing clinical trial comparing computer-assisted navigation versus the freehand approach11. To date, this trial has not yielded any conclusive results. As such, a larger and more comprehensive investigation is necessary to assess the potential benefits and risks of these two EVD placement techniques. Similar to other studies10, our study showed no difference in the incidence of tract hemorrhage when an EVD was placed at the bedside versus in the OR.

This study has several strengths, including the provision of a standardized treatment approach to the study population and the inclusion of predictors of tract hemorrhage after EVD placement that were not considered in previous studies. However, the present study has some limitations. It is a single-center study with a limited sample size, which compromises the ability to establish associations between the use of a neuro-navigation system and study outcomes. Additionally, other etiologies of ICP elevation, such as infection or idiopathic hydrocephalus, may have been underrepresented. Finally, the number of EVD placement attempts was not considered in this study due to the lack of information in the medical records.

In conclusion, the current study found that patients with platelet counts < 120 × 10³/µL, WBC counts < 11 × 103, and IPH were at significantly higher risk for tract hemorrhage following EVD placement. Our findings, together with those from previous studies, show that several patient factors should be considered to help reduce hemorrhage risk and other complications after EVD placement. Further investigation is necessary to confirm the current findings of this study, expand upon them, and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy reasons, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

AlAzri, A., Mok, K., Chankowsky, J., Mullah, M. & Marcoux, J. Placement accuracy of external ventricular drain when comparing freehand insertion to neuronavigation guidance in severe traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir. (Wien). 159, 1399–1411 (2017).

Bauer, D. F., Razdan, S. N., Bartolucci, A. A. & Markert, J. M. Meta-analysis of hemorrhagic complications from ventriculostomy placement by neurosurgeons. Neurosurgery. 69, 255–260 (2011).

Kakarla, U. K., Kim, L. J., Chang, S. W., Theodore, N. & Spetzler, R. F. Safety and accuracy of bedside external ventricular drain placement. Neurosurgery. 63, ONS162–ONS167 (2008).

Jackson, D. A. et al. Safety of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) thrombolysis based on CT localization of external ventricular drain (EVD) fenestrations and analysis of EVD tract hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 19, 103–110 (2013).

Gardner, P. A., Engh, J., Atteberry, D. & Moossy, J. J. Hemorrhage rates after external ventricular drain placement. J. Neurosurg. 110, 1021–1025 (2009).

Sussman, E. S. et al. Hemorrhagic complications of ventriculostomy: incidence and predictors in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 120, 931–936 (2014).

Bauer, D. F., McGwin, G. Jr., Melton, S. M., George, R. L. & Markert, J. M. The relationship between INR and development of hemorrhage with placement of ventriculostomy. J. Trauma. 70, 1112–1117 (2011).

Miller, C. & Tummala, R. P. Risk factors for hemorrhage associated with external ventricular drain placement and removal. J. Neurosurg. 126, 289–297 (2017).

Morotti, A. et al. Leukocyte count and intracerebral hemorrhage expansion. Stroke. 47, 1473–1478 (2016).

Phillips, S. B., Delly, F., Nelson, C. & Krishnamurthy, S. Bedside external ventricular drain placement: can multiple passes be predicted on the computed tomography scan before the procedure? World Neurosurg. 82, 739–744 (2014).

Ahmed, A. External ventricular drain placement stealth study. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03696043. (2023). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03696043

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lead Medical Writer Anne Murray, PhD, MWC® of the Clinical Research Institute at Methodist Health System for providing editorial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RM, EV, BD, and JCBG made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; and drafted the work or substantively revised it. All authors have have approved the submitted version and have agreed both to be personally accountable for their own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Meyrat, R., Vivian, E., Dulaney, B. et al. Predictors of tract hemorrhage after external ventricular drain placement: a single-center retrospective study. Sci Rep 14, 27772 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79421-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79421-z