Abstract

The cultivation of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in semi-arid regions is affected by drought. To explore potential alleviation strategies, we investigated the impact of inoculation with Bacillus velezensis, and the application of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) via foliage application (FA), which promote plant growth and enhance stress tolerance. A split-split-plot experiment with four replications was conducted, featuring two irrigation levels: full watering (FW, 100% of plant water requirements) and deficit watering (DW, 70% of plant water requirements) as a main plot, two ASA levels (No foliage application (NFA) 0 and 0.5 mM) as sub plot, and bacterial inoculation (BI) versus non-bacterial inoculation (NBI) as sub-sub plot. Results showed that the highest grain yield was achieved with the ASA + BI under FW (3270 kg ha−¹), a 56% increase compared to the control (2094 kg ha−¹). Under DW, the ASA + BI increased yield by approximately 30%. ASA significantly increased relative water content under deficit watering, achieving 84% with BI. Chlorophyll a content peaked at 3.11 mg g− 1 with full watering, and chlorophyll b content increased by up to 23.8% under deficit watering, indicating improved photosynthetic capacity. Malondialdehyde and hydrogen peroxide levels were reduced to 10.88 and 14.81 µmol g−¹ fresh weight, respectively, in ASA + BI treatments, demonstrating reduced oxidative stress. Antioxidant enzyme activities were significantly elevated in treated plants under DW. This study demonstrates the potential of microbial and hormonal treatments in boosting drought tolerance in common beans, providing a viable approach for sustaining crop performance under stress conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Legumes are vital sources of protein and cost-effective providers of carbohydrates, micronutrients (such as iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn)), vitamins, folic acid, and fiber1. In addition to their nutritional benefits, they enhance cropping systems by symbiotically fixing nitrogen2, which improves soil fertility. However, despite the increasing demand for legumes, water scarcity presents a significant challenge to common bean (CB) production, posing a threat to global food security3,4. In semi-arid regions like Iran, common beans are usually planted between mid-April and early July, depending on local climate and regional conditions (https://www.amar.org.ir/english/Statistics-by-Topic/Climate-and-Environment). This extended planting window exposes the crop to a range of environmental conditions, partially mimicking climate change scenarios such as rising temperatures5.

Drought conditions can drastically reduce common bean (CB) yields, leading to a 49% decline during flowering and a reduction of 58–87% during the reproductive stages6. Physiological responses are sensitive indicators of plant health and environmental stress. Water stress disrupts physiological and biochemical processes, affecting water balance and photosynthesis, increasing oxidative stress and membrane damage, and inhibiting enzymatic activities, all of which contribute to reduce crop yields7. Severe drought worsens these issues by impairing stomatal function and reducing the activity of enzymes responsible for CO₂ absorption, leading to a decrease in photosynthesis rates8,9. Furthermore, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) during drought stress induces lipid peroxidation, protein degradation, and DNA damage, compromising cell membrane integrity10. However, plants have evolved a robust antioxidant defense system, comprising both enzymatic and non-enzymatic components, to combat ROS toxicity11. Research highlights the critical role of antioxidant enzymes in reducing oxidative stress by scavenging ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) and malondialdehyde (MDA) under drought conditions. Elevated levels of ROS are marker of oxidative damage, which negatively impacts cellular health12. In contrast, increased concentrations of chlorophyll and carotenoids indicate enhanced photosynthetic capacity, while osmolytes like proline, soluble sugars, and proteins aid in osmotic adjustment, enabling plants retain water and tolerate drought stress13.

The use of Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) offers an eco-friendly and sustainable strategy to mitigating drought stress while promoting plant growth under optimal water conditions14. PGPR inoculation has been shown to decrease proline levels, reduce lipid peroxidation, and regulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes including catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), which are typically elevated under drought stress. This approach has proven effective in crops such as chickpea, wheat, soybean, and green beans15,16,17,18. Growth-promoting bacteria, such as Pseudomonas spp., Bacillus spp., and Acinetobacter spp., have been shown to effectively manage abiotic stresses through mechanisms like the production of exopolysaccharides (EPS), which help plants withstand adverse environmental conditions¹⁹. Species within the Bacillus genus, particularly, Bacillus velezensis, promote plant growth by inhancing nutrient uptake, hormone production, and the emission of volatile compounds20. Additionally, they improve drought resistance in Brachypodium distachyon, by increasing leaf carbohydrate and starch content21. Bacillus velezensis, including the UTB96 strain, has gained recognition as an effective plant probiotic. Initially classified as Bacillus subtilis UTB96, this strain was later reclassified as Bacillus amyloliquefaciens UTB96 and registered in GenBank under accession number KY99285722. Subsequent studies, including those by Vahidinasab et al. (2019)23, using 16 S rDNA analysis and whole-genome sequencing, further identified the strain as Bacillus velezensis UTB96. Numerous studies underscore the potential of Bacillus velezensis as an eco-friendly alternative to synthetic fertilizers in agriculture. This beneficial bacterium promotes plant growth by producing antimicrobial agents, suppressing plant pathogens, and enhancing nutrient uptake and stress resilience across various crops, making it valuable asset for advancing sustainable farming practices24.

Salicylic acid (SA) and its derivative, acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), are phytohormones recognized for their crucial role in protecting plants from abiotic stresses, such as drought25,26, and mitigating oxidative damage associated with these stresses27. These signaling molecules regulate various physiological processes, including ion transport28, photosynthesis, membrane permeability, gene expression, and the absorption and distribution of essential elements29. The interaction between rhizobacteria such as Bacillus subtilis and hormones like SA under drought stress has been shown to positively influence plant growth, hydration, photosynthesis, osmoregulation, enzyme activity, and nutrient uptake in crops like white beans and tomatoes30,31. While the independent benefits of PGPR and ASA have been well documented, limited research has explore their combined effects, particularly under varying environmental conditions, such as those created by different planting dates.

In this study, the selection of planting dates—early May and late June—spans a 45-day period with varying temperature and humidity, simulating a range of environmental conditions. This approach provides a more comprehensive understanding of how common beans respond to climate variability and potential long-term climate changes beyond a typical two-month window. Given the urgent need to enhance crop resilience against increasing drought stress, particularly in semi-arid regions, this study hypothesizes that the interaction between ASA and bacterial inoculation (BI) will improve drought tolerance by: (1) increasing antioxidant enzyme activity, (2) elevating osmolyte levels, (3) improving relative water content, and (4) raising chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoid concentrations. Additionally, ASA and BI application may reduce MDA and H₂O₂ levels, thereby mitigating the adverse effects of drought.

This research seeks to address two key questions: How do Bacillus velezensis and ASA treatments affect the physiological and biochemical responses of common beans under drought stress? Can these treatments significantly enhance drought tolerance and maintain productivity under drought conditions across both planting dates?

Results

The results demonstrated the significance of main effects and interactions on grain yield and various physio-chemical indices measured in CB. Below, we demonstrate and describe how the experimental treatments affect CB yield and physio-chemical indices.

Grain yield

The interaction between hormones and bacteria under full watering (FW) significantly increased grain yield compared to treatments without these inputs. However, under deficit watering (DW), this interaction did not differ significantly from the no-foliage application and non-bacteria inoculation (NFA + NBI), though it did show a meaningful difference from the control. The combination of hormone and bacteria under FW notably enhanced grain yield while under DW, this combination did not significantly impact yield. In May 2021, the treatment combining FW with ASA foliage application (ASAFA) and (BI) produced the highest yield of 3,270 kg ha−¹, significantly surpassing the control yield of 2,094 kg ha−¹. Data from 2022 indicated slight variations in treatment effectiveness, suggesting that while FW generally improves yield compared DW, the addition of ASAFA and BI yielded mixed results (Fig. 1).

Effects of deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI) on yield in common beans during May and June of 2021 and 2022.

Leaf relative water content (RWC)

In the ASAFA treatment, both with and without bacterial inoculation (BI and NBI), there was a notable preservation of RWC compared to NFA, suggesting that salicylic acid may mitigate some effects of water stress (Fig. 2). For example, in May 2021 under DW, the hormone-treated plots exhibited RWC values of 77% (with bacteria) and 76% (without bacteria), compared to a lower 74.40% in the control. Similarly, under FW, ASA-treated plants maintained higher RWC (82.4% with BI and 82.1% without BI) compared to the control (81%). This trend persisted in 2022, where in May, ASA under DW again resulted in higher RWC (84% with BI and 83% without BI) compared to the control (81%). (Fig. 2).

Effects of deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI) on the relative water content in common beans during May and June of 2021 and 2022.

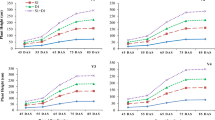

Chlorophyll and carotenoid contents

Under drought conditions, plants treated with BI and ASAFA exhibited higher levels of chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), and carotenoids compared to untreated plants. Specifically, in June 2021 and 2022 under FW, BI-treated plants showed higher Chl a content, measuring of 2.56 and 3.11 mg g−¹ fresh weight (FW), respectively. Under 70% irrigation, ASAFA alone increased Chl a to 1.83 mg g−¹ FW in 2022, while the combination of BI and ASAFA raised it to 1.85 mg g−¹ FW across both planting dates in 2021, which represented increases of 23% and 98% compared to the control (Fig. 3a). Additionally, BI-treated plants had Chl b increases of 0.79 and 0.64 mg g⁻¹ FW under full irrigation in June 2021 and 2022, respectively. In contrast, the DW treatment showed smaller increases of 23.8% and 9.43% compared to the control in June of both years (Fig. 3b). The highest carotenoid content (0.43 mg g−¹ FW) was recorded under FW with the BI and ASAFA combination in June 2022. This combination also resulted in the highest carotenoid concentration (0.26 mg g−¹ FW) under drought stress, while other treatments did not show significant differences from the control (Fig. 3c). Strong positive correlations among photosynthetic pigments suggest that their levels typically rise or fall together, reflecting changes in photosynthetic capacity (Fig. 4).

Effects of deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI) on the contents of chlorophyll a (a), chlorophyll b (b), and carotenoids (c) in common beans during May and June of 2021 and 2022.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot showing the relationships among various physiological and biochemical traits in common beans under deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI). Positive correlations are indicated by vectors pointing in the same direction, while negative correlations are indicated by vectors pointing in opposite directions. Key parameters include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), malondialdehyde (MDA), relative water content (RWC), proline (Pro), various chlorophyll contents (Chl.a, Chl.b, T.Chl), carotenoids (Cart), antioxidant enzymes (APX, GPX, CAT, SOD) and grain yield (GY).

Effects of deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI) on the production of hydrogen peroxide (MDA; a) and malondialdehyde (H2O2; b) in common beans during May and June of 2021 and 2022.

Lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species changes

Alterations in reactive oxygen species, such as hydrogen peroxide and malondialdehyde (MDA), were observed in response to drought stress (Fig. 5a, b). Over the two-years of study, significant variations in MDA levels were recorded across different treatments. In plots treated with BI, those receiving ASAFA consistently exhibited lower MDA levels compared to the control under both irrigation regimes. For instance, under drought stress, MDA concentrations were 13.06 µmol g−¹ FW in June 2021 and 14.75 µmol g−¹ FW in May 2022. In contrast under FW even lower values were observed at 10.98 µmol g−¹ FW in 2021 and 10.88 µmol g−¹ FW, in 2022. In plots, without BI, higher MDA levels were recorded, with the highest concentrations reaching 18.47 µmol g−¹ FW in 2021 and 19.90 µmol g−¹ FW in 2022 under DW with NFA or NBI treatments (Fig. 5a).

Drought stress led to an increase in H2O2 production (Fig. 5b). However, under DW, plots treated with ASAFA and BI exhibited a smaller rise in H2O2 compared to untreated plants. The highest recorded level of H₂O₂ concentration was 18.79 nmol g⁻¹ FW in June 2021 under DW with ASAFA and BI, compared to 14.24 nmol g⁻¹ FW in the control. In contrast the same treatment under FW in June 2022 showed a lower H₂O₂ concentration (14.81 nmol g− 1 FW) while the control showed an amount of 11.41 nmol g− 1 FW, suggesting that adequate hydration might alleviate some of the oxidative stress responses under DW. MDA and H2O2 serve as indicators of lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress, respectively. Their co-expression alongside antioxidant enzymes offers valuable insights into the balance between ROS production and scavenging, revealing the effectiveness of stress mitigation strategies (Fig. 4).

Osmolytes contents

The experimental results show that the combination of ASAFA and BI under DW produced the highest carbohydrate concentrations, measuring 0.33 mg g−¹ FW in 2021 and 0.34 mg g−¹ FW in 2022. In contrast, FW (100%) consistently resulted in slightly lower carbohydrate levels of 0.254 mg g−¹ FW and 0.251 mg g−¹ FW in June of both years. This similarity in carbohydrate levels between FW and ASAFA + BI treatments under DW highlight the critical role of bacteria in enhancing carbohydrate synthesis, suggesting that bacterial presence had a greater impact on carbohydrate production than ASAFA alone (Fig. 6a).

Effects of deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI)) on the concentrations of total soluble sugars (a), soluble proteins (b), and proline (c) in common beans during May and June of 2021 and 2022.

In 2022, plants treated with ASAFA and BI under DW exhibited a significant increase in protein content, reaching 20.98 mg g−¹ FW in May, the highest value (across all treatments and conditions), compared to 16.60 mg g−¹ FW in the control. Under FW, the same treatment also resulted in the highest protein content of 18.7 mg g−¹ FW in June 2022, while the control showed protein levels of 12 mg g−¹ FW in the first year and 17 mg g−¹ FW in the second year (Fig. 6b).

In June 2021, plants treated with BI and ASAFA had a proline content of 7.22 mg g−¹ FW under DW, compared to 5.7 mg g−¹ FW in the control. In contrast, under FW, the same treatment combination (ASAFA and BI) had a proline content of 6.68 mg g−¹ FW, which was not significantly different from the control at 6.08 mg g−¹ FW. In 2022, the combination of ASAFA and BI under water stress resulted in a higher proline content of 6.9 mg g−¹ FW. This suggests that proline accumulation increased under reduced water availability, likely as a response to osmotic stress, while under FW, the same treatment showed a much lower proline content of 2.78 mg g−¹ FW in June (Fig. 6c).

Antioxidants enzyme activity

Antioxidant enzymes typically exhibit strong positive correlations with each other, indicating that they are often co-induced or co-suppressed in response to oxidative stress (Fig. 4). For example, high levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) often coincides with elevated catalase (CAT) activity across various treatments, suggesting a positive correlation between these enzymes in managing oxidative stress. Additionally, analysing colour patterns vertically allows for a clearer observation of how different treatments affect each marker. Treatments that produce similar color changes across multiple markers may indicate the activation of broader stress response pathways in plants (Fig. 7).

Heatmap and cluster analysis of oxidative stress responses under various irrigation and treatment conditions. This figure illustrates the differential expression of oxidative stress-related markers and antioxidant enzymes under deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI). The heatmap uses a color gradient from blue (low expression) to red (high expression) to represent the standardized values of each parameter. The top dendrogram clusters treatments based on similarity in response patterns, and the left dendrogram groups the biochemical markers. A color key and histogram on the left display the distribution of expression levels across all conditions.

In May 2021 and June 2022, the highest ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity levels were recorded under DW with ASAFA and BI treatments, measuring 3.24 and 4 U min−¹ g−¹ FW, respectively, compared to the control (1.13 and 2.62 U min−¹ g−¹ FW), indicating a substantial increase. Under FW in both years, the lowest APX activities (0.40 and 0.44 U min−¹ g−¹ FW) were observed in the combination treatments (ASA + BI) and bacteria alone, compared to the control (0.06 and 0.7 U min−¹ g−¹ FW), demonstrating a non-significant enhancement (Fig. 8a).

Effects of deficit watering (DW) and full watering (FW), with or without hormone application (ASAFA for acetylsalicylic acid foliar application and NFA for no foliar application), and bacteria inoculation (BI) versus non-bacteria inoculation (NBI) on the enzymatic activities of glutathione peroxidase (GPX; a), catalase (CAT; b), superoxide dismutase (SOD; c), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX; e) in common beans during May and June of 2021 and 2022.

The combination of BI and ASAFA resulted in the highest CAT activity (0.81 and 1.04 U min−¹ g−¹ FW) under DW in June 2021 and May 2022, respectively. This represented a significant increase of 69% and 104.51% compared to the control (0.35 and 0.37 U min−¹ g⁻¹ FW). Conversely, the lowest CAT activity levels were observed under FW. In June 2021, BI with FW reduced CAT activity to 0.20 U min⁻¹ g⁻¹ FW, a 42.86% decrease compared to the control (0.35 U min−¹ g−¹ FW). This trend continued in May 2022, where CAT activity further decreased to 0.22 U min−¹ g−¹ FW, a 40.54% reduction compared to the control (0.37 U min−¹ g−¹ FW) (Fig. 8b).

Glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activity increased significantly reaching 0.05 and 0.06 U min⁻¹ g⁻¹ FW in response to drought stress, particularly in the hormonal and bacterial treatments in June 2021 and 2022. Under FW in June 2021, GPX activity (0.026 U min−¹ g−¹ FW) was observed with the combination of ASAFA and BI, approximately 24% higher than the control (0.021 U min−¹ g−¹ FW). This trend continued into 2022, with the same treatment showing a GPX activity of 0.032 U min−¹ g−¹ FW, 23% higher than the control (0.026 U min−¹ g−¹ FW). The lowest GPX values (0.022 and 0.024 U min−¹ g−¹ FW) were recorded under optimal irrigation with bacteria in May 2021 and 2022, respectively, which did not differ significantly from the control (Fig. 8c).

The highest SOD enzyme levels were recorded in June 2021 and 2022, with values of 0.12 and 0.10 U min−¹ g−¹ FW, respectively, under drought stress with ASAFA and BI. In contrast, the lowest SOD activity was 0.01 U min−¹ g−¹ FW in June 2021 under normal irrigation with hormones but without bacteria, and 0.02 U min−¹g−¹ FW in May 2022. These lowest activities showed no significant differences across months with full irrigation. In control conditions (NFA and NBI), the lowest value was 0.04 U min−¹ g−¹ FW under 100% water requirement, while the highest was 0.08 U min−¹ g−¹ FW under DW, recorded in May 2021 and June 2022, respectively (Fig. 8d).

Discussion

Impact of drought on common bean yield

The results demonstrate that water deficit significantly hampers the growth and productivity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) (Fig. 1). Drought impairs physiological and biochemical processes, resulting in substantial reductions in pod number, seed count, and overall yield32,33. In semi-arid regions like Iran, where the average annual rainfall is around 250 mm, drought poses a major challenge. The use of accessible, cost-effective, and eco-friendly treatments such as plant PGPR and ASA shows promise in mitigating drought impacts. In 2021, the combined application of ASA and Bacillus significantly improved yield under deficit irrigation. However, in 2022, the response was less pronounced, likely due to environmental variations, including lower rainfall and higher temperatures, which intensified water stress and reduced plant growth and stress responses. Despite this, our findings underscore the effectiveness of PGPR and ASA treatments in mitigating drought-induced yield losses under limited irrigation.

Effect of planting dates on treatment response

The planting dates (early May and late June) were selected to simulate varying environmental conditions including temperature fluctuations. Early May planting benefited from cooler temperatures and a longer growing season, while late June planting exposed plants to higher temperatures and drought, increasing their reliance on treatments for enhanced physiological and biochemical responses. These treatments helped plants maintain higher RWC, reducing water stress and preserving essential metabolic functions during dry conditions25.

Photosynthesis and chlorophyll content under drought

Our findings align with previous research demonstrating that these treatments sustain agronomic traits while boosting photosynthetic and antioxidant capacities under drought conditions34,35. Notably, there is limited research on pulse biofortification under drought stress36. Drought-induced declines in photosynthesis result from a complex interplay of physiological activities within the leaves37. More severe reduction in biochemical traits under drought conditions correlates with lower photosynthesis and limited recovery after re-watering7. In this study, BI particularly when combined with ASA, increased chlorophyll levels under both control and drought conditions, enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and yield. The strong correlation between chlorophyll a, b, and carotenoids highlights their importance in maintaining the photosynthetic system (Fig. 7). Conversely, reductions in chlorophyll content during drought can impair photochemical functions in chloroplasts, reducing photosynthesis8. Therefore, increasing the total amount of photosynthetic pigment per unit leaf area can enhance the rate of photosynthesis.

Oxidative stress and antioxidant defense mechanisms

ROS, including H₂O₂, disrupt photosynthesis by reducing turgor pressure and altering chlorophyll properties, leading to peroxidation and damage19. Drought conditions, along with microbial inoculation and ASA treatments, influence the levels of MDA and H₂O₂ (Fig. 4a, b), which serve as indicators of oxidative stress and cellular damage38. The accumulation of these markers in NBI treated plants during drought suggests a weakened antioxidant defence, leading to yield losses39,40 due to impaired growth and increased cell death41,42. The negative correlation between RWC and oxidative stress markers supports the view that DW exacerbates cellular damage43 (Fig. 7). Treatments involving ASA and PGPR significantly reduced oxidative stress markers, improving water relations and enhancing drought tolerance44. The reduction in MDA levels further supports the hypothesis that these treatments reduce membrane damage, a hallmark of oxidative stress. A positive correlation between H₂O₂ and MDA indicates that elevated H₂O₂ promotes lipid peroxidation, leading to cell membrane damage. The ability of ASA and BI treatments to maintain higher antioxidant enzyme activity and chlorophyll content while reducing MDA and H₂O₂ levels demonstrates their effectiveness in protecting cellular structures, and maintaining photosynthetic efficiency, particularly under DW (Fig. 7). This finding aligns with studies showing that PGPR inoculation enhances drought tolerance in crops like Solanum tuberosum and Phaseolus vulgaris by preventing membrane damage7,32.

Role of osmolytes contents

The increase in proline levels observed with ASA treatment, particularly under drought, is aligns with previous findings that link higher ASA concentrations to greater proline production45. This protective response was absent in treatments without ASA, where the lowest proline levels were recorded46. Soluble protein content also decreased under drought, reflecting reduced photosynthetic activity and limited substrate availability for protein synthesis47. However, plants treated with 0.5 mM ASA and Bacillus spp. maintained higher protein levels under both normal and stressed conditions, with statistically significant differences (p < 0.05), confirming the efficacy of the treatments in mitigating drought effects (Fig. 8). Osmolytes, such as soluble sugars, proteins, and proline, help plants maintain cell turgor at low water potential, sustaining metabolic processes during stress48,49. Plants with higher carbohydrate reserves perform better under stress by mobilizing these reserves to support reproductive development and yield, when photosynthesis is limited due to water stress50. Our research revealed a positive correlation between carbohydrate content and grain yield (Fig. 7), consistent with previous studies linking carbohydrate reserves to improved yield under stress conditions51.

Role of antioxidant enzymes

The enhancement of antioxidant enzyme activities particularly CAT, APX, SOD, and POD was a notable outcome of ASA and BI (Fig. 8). This increase, consistent across both years and irrigation regimes, suggest that these treatments strengthen the antioxidant defence system, reducing oxidative stress and improving drought tolerance. CAT and POD activities play a crucial role in breaking down H₂O₂ into water (H2O) and oxygen (O2), while APX reduces H₂O₂ using ascorbate, an essential mechanism under drought conditions. The elevated APX activity during drought helps prevent the accumulation of ROS, which would otherwise lead to cellular damage52. Higher enzymes activity such as APX is particularly advantageous under drought conditions as it maintains a balance between ROS production and scavenging, preventing excess accumulation of ROS, which can severely impair cell structure and function. The increase in APX activity ensures that H₂O₂ is efficiently detoxified, thereby protecting chloroplasts and maintaining efficient photosynthesis, even under water deficit conditions. This enhanced ROS scavenging capacity ultimately contributes to improved drought tolerance in the treated plants53. SOD is essential for dismutation superoxide radicals into H₂O₂ and O2, serving as the first line of defence against ROS by reducing the superoxide anion, one of the most reactive and harmful ROS54. This cascade of antioxidant enzyme activities minimizes oxidative damage, especially under water-limited conditions, thereby protecting essential cellular processes, including photosynthesis for example in faba beans (Vicia faba), drought stress significantly enhanced both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant activity compared to normal moisture conditions55.

Gene regulation and drought-inducible mechanisms

These physiological responses are regulated by drought-inducible genes and stress-signaling pathways, such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), which mediate drought tolerance at the molecular level56. Our results indicate that drought triggers significant changes in gene expression, particularly in genes involved in osmotic adjustment and antioxidant defence. This is evident in the accumulation of proline, which is regulated by drought-inducible genes. These genes encode enzymes that synthesizing osmolytes like proline, helping to maintain cellular homeostasis under stress57.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study shows that water deficit severely impacts the growth and yield of common bean, specially during critical stages such as flowering and seed filling. The application of BI and ASA treatments mitigated these drought-induced effects by enhancing several physiological and molecular mechanisms. These treatments improved water balance by maintaining higher RWC and reduced oxidative stress through elevated activities of antioxidant enzymes (CAT, APX, SOD, POD), which helped protect cellular structures and preserve photosynthetic efficiency. Elevated proline levels and chlorophyll content further supported osmotic adjustment, sustaining photosynthetic activity under drought conditions. Furthermore, lower MDA and H₂O₂ levels promoted membrane stability, while the activation of stress-responsive genes likely bolstered these protective responses. Overall, BI and ASA treatments enhanced drought tolerance by driving both physiological and molecular adaptations, offering a promising approach to improving crop resilience in semi-arid regions.

Materials and methods

Experimental location and design

This study investigated the effects of plant growth regulators on the growth and yield of common beans under drought stress in a field trial. The experiment was conducted in early May (7th) and late June (20th) of both 2021 and 2022 at the University of Tehran’s research farm in Karaj, Iran (35°56’ N, 50°58’ E). These planting dates were selected based on historical weather data to represent early and late planting seasons in this semi-arid region, allowing for evaluation of treatment responses under varying environmental conditions. The experiment was arranged in a split-split plot design with four replications. The main plot factor included two irrigation regimes: deficit watering (70% of the plant water requirement) and full watering (100% of the plant water requirement). The sub-plot factor involved two levels of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) application: 0 mM and 0.5 mM. The sub-sub plot factor included inoculation with Bacillus velezensis or no bacterial inoculation. The control treatment included no foliage application with ASA (NFA) treatment, non-bacterial inoculated plants (NI)). Common bean seeds were sourced from the gene bank of the University of Tehran’s Agronomy Department. The experimental site was prepared through ploughing and disking, with soil testing conducted by the university’s Soil Science Department. The trial covered a uniform clay-loam area of 750 m², with 22 m by 17 m per planting date, encompassing 32 plots (3 m in length and 2 m in width). Spacing was maintaned at 50 cm between sub-sub plots, 1 m between sub plots, 2 m between main plots, and 1.5 m between replications. Row and plant spacing were 30 cm and 5 cm, respectively, resulting in a planting density of 20 plants per m². Seeds were sown at a depth of 3–5 cm, with 32 plots (6 m² with 4 rows) used for each planting date. Irrigation was applied using drip lines placed along each row. Control plants were maintained under the same environmental and agronomic conditions as treated plants, including identical watering, soil preparation, and spacing. Non-bacterial inoculated controls were managed using aseptic techniques to prevent contamination.

Drought stress application

The crop water requirement (CWR) was determined using CROPWAT 8.035, software which integrates rainfall, soil, crop, and environmental data to estimate reference evapotranspiration (ET₀) and optimize irrigation scheduling58. The methodologies adhere to the FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper, facilitating improved irrigation planning for both irrigated and rainfed conditions59,60. Climate data were obtained from the Karaj meteorological station (Table 1), and soil data were provided by the Soil Science Department at the University of Tehran (Table 2). during two years of study. Soil moisture content was monitored using time domain reflectometry (TDR) at depths of 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm in different plots.

Transpiration of common bean plants was calculated under drip irrigation conditions using the following Eq. 1.

Td represents transpiration (mm/day), ETc is the crop evapotranspiration (mm/day), p is plant density (plants/m²), and d is plant height (cm).

The daily water requirement in partial drip irrigation, calculated (based on plant shading percentage), was determined for100% and 70% treatments and scheduled every four days, with 90% efficiency across 21 irrigation sessions. Irrigation depths were calculated: 6.44 mm for 100% and 4.308 mm for 70% with a 0.7 coefficient. Crop coefficients for the common bean were based on FAO guidelines: 0.4 during early growth, 1.15 during mid-development to late flowering, and 0.35 during grain formation60. These coefficients were adjusted to reflect the region’s specific climatic conditions. Stress was applied from the onset of crop growth until the final irrigation, using data obtained from the CROPWAT 8.0 software.

Kcmid (Tab) and u2 are the crop coefficient values and average daily wind speed at a height of two meters (m/s). RHmin indicates the average minimum daily relative humidity (%), and h is the average plant height (m).

After adjusting the crop coefficients for regional climatic conditions, the values were entered into the CROPWAT software to calculate the evapotranspiration of the target crop. The total volume of water used for each irrigation cycle was quantified, with water flow monitored using flumes sized 92 × 20 cm. The duration of each irrigation treatment was measured with a chronometer61. A drip irrigation system featuring emitters with 3.1 L h− 1 and spaced every 10 cm apart, was powered by a steam pump delivering 20–90 L min− 1 at 25–45 atm. Filtration was handled by a mesh filter, and water volume was regulated by a flow meter.

Plant growth and yield

Harvesting accurred at physiological maturity, as determind by the BBCH scale62. Seeds were manually from a designated 1 m² area, excluding border rows, once the pods transitioned from yellow to brown. In each plot, five plants were randomly selected for measurement, and the average of these measurements was reported across four replicates. After drying the seeds to 14% moisture content, seed weight was recorded using a digital scale with 0.01 g precision, and yield was expressed in kg ha− 1.

Plant growth regulators application

Bacteria strains: Bacterial isolates (Bacillus velezensis strain UTB9663) were obtained the from bacterial collection of University of Tehran, Iran. Strain UTB96 was previously identified through biochemical tests and 16 S rRNA gene sequencing, as recorded under NCBI accession number KY99285723,24 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/KY992857) (Table 3). To prepare the bacterial inoculum, a full loop of a 48-hour bacterial culture was transferred to Erlenmeyer flasks containing 100 mL of LB medium (1 g proteose peptone, 0.5 g of yeast extract, 1 g NaCl in sterile water (pH 6.8))65. The flasks were incubated for 48 h in a shaker incubator set at 180 rpm and 30 °C. Bacterial cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min and their concentration was adjusted to 108 cells/mL using a spectrophotometer. Before inoculating, the seeds were soaked in 70% ethanol for 1 min and 1.5 (w/v) sodium hypochlorite for 1 min, followed by three washes with sterile water. The seeds were then inoculated in the bacterial suspension for 6 h at 180 rpm in a shaker incubator set to 30 ± 1°C65.

Acetylsalicylic Acid (ASA)

2-Ethoxybenzoic Acid, O-Acetylsalicylic Acid, and Aspirin, was obtained from Merck & Co., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. A preliminary experiment was conducted to assess the seeds’ response to various concentrations of ASA with 0.5mM being selected as it resulted in the highest germination percentage and rate. A MATABI backpack sprayer (T-Jet VS11004 spraying nozzle with a 110° angle and a flow rate of 0.4 US gallons per minute) was used to apply the hormone at 30 and 60 days after seed cultivation. The spray was administered at a distance of 20 cm from the plants in the morning hours, when temperatures ranged between 15 and 20 °C.

Biochemical traits

A UV-1100 absorption spectrophotometer was used to measure the total carbohydrate, soluble protein, proline, chlorophyll a, b, carotenoid, MAD, H2O2, and enzyme activity, including CAT, SOD, GPX and APX. For the various treatments, 1 g of leaves was weighed, using an electronic balance, and then ground into a fine powder using pestle and mortar, with liquid nitrogen to assist in crushing process. Next, 10 ml of 0.02 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) was added to the powder, and the formed slurry transferred to 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. To extract the supernatant from the mixture, the Eppendorf tubes. To extract the supernatant, the tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min using a MIKRO 120 Hettich Centrifuge 4108. The supernatant was carefully drawn off with a micropipette and transferred to a separate tube for analysis.

Relative water content (RWC)

This trait was measured using the method described by Barrs and Weatherly 196266. The RWC calculated as a percentage using the following equation, where FW represents the fresh weight of the sample, DW represents the dry weight, and TW represents the turgid weight of the sample.

Chlorophyll and carotenoid

According to Ye et al. 201967, 0.1 g of crushed leaf material was homogenized in 80% acetone and vortexed for 1 min. The samples were left to stand at room temperature for 30 min before being centrifuged at 4 °C, 12,000 g for 15 min. The green supernatant was then separated, and its absorbance of this green supernatant measured at 645, 663, and 470 nm using spectrophotometer Shimadzu UV160U UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration

MDA levels were measured using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) method described by Predieri et al. 199568. For this 0.2 g of crushed leaves were mixed with 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), vortexed for 60 s, and then centrifuged for 10 min. The sample was homogenized with 0.5% TBA in 20% TCA and heated in a steam bath at 100 °C for 30 min. After immediate cooling in ice and a second centrifugation, the absorbance was measured at 532 and 600 nm. MDA levels were calculated using a molar absorbency index of 155 mM− 1 cm− 1 and expressed as nmol mg− 1 FW.

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

Initially, 0.5 g of crushed leaves were thoroughly mixed with liquid nitrogen and 0.1% TCA, then centrifuged for 10 min at 16,000 g. Before dissolving 1 M potassium iodide in the mixture, an equal volume of the liquid phase from the centrifuged samples was blended with a phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7). The absorbance of the resulting solution was ultimately measured at 390 nm69.

Total soluble sugar

The Schlegel, 1956 method70 was used to measure soluble sugars in leaf tissue. For this, 0.2 g of leaf tissue was heated with 10 mL of 95% ethanol at 80 °C for one hour, followed by cooling. Then, 1 mL of the sample was mixed with 1 mL of 0.5% phenol solution and 5 mL of 98% sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) and left at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 483 nm using a spectrophotometer, and carbohydrate content was calculated based on a glucose standard curve.

Total soluble proteins

To determine total protein concentration, 0.1 g of powdered, crushed leaves was mixed with an enzymatic extraction buffer consisting of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) ethylene diamine tetra acetate acid (EDTA), and Triton X-100 in a 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6). The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min. The resulting liquid phase was transferred to plastic tubes and stored at -80 °C for subsequent protein and enzyme activity analysis71. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as the standard to creating a calibration curve for quantify protein levels, which were expressed in mg g− 1 of fresh weight based on absorbance measurements at 595 nm.

Proline

To measure proline content, 0.5 g of frozen leaves was vortexed with 5 ml of 3% w/v H2SO4, and centrifuged at 15,000 g for 20 min. Then 2 ml of the supernatant was mixed with 2 ml of ninhydrin solution, heated over steam at about 100 °C, rapidly cooled to 3 °C, and vortexed with toluene for 20 s. After heating the solution in a boiling water bath for 1 h and immediate cooling on ice, it was vortexed again with 4 ml of toluene for 20 s. The absorbance at 520 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer. L-proline was used for the standard curve, with a protein extraction-free sample serving as the control, following the methods described by Bates et al. 197372.

Enzymatic antioxidant activities

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX)

Enzyme activity measured using the method of Ranieri et al. 200373. In this method the reaction between APX, ascorbic acid, and H2O2 produces dehydroascorbate, which is detected at a wavelength of 290 nm. The reaction medium contained 600 µL of 0.1 mM EDTA, 1500 µL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7), 400 µL of 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, 400 µL of 30% H2O2, and 50 µL of enzyme extract. The enzyme activity was measured over 7 min at 20-second intervals.

Catalase (CAT)

CAT enzyme activity at 25 °C was measured using a spectrophotometer following the method of Aebi, 198474. The spectrophotometer, manufactured in Japan, was set to a wavelength of 240 nm to monitor enzyme activity. The reaction mixture contained 3000 µL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7), 5 µL of 30% H₂O₂, and 50 µL of enzyme extract. Enzyme activity was recorded over 5 min, with measurements taken at 20-second intervals. The specific activity of the enzyme was expressed as micromoles of H₂O₂ decomposed per minute per mL of protein.

Glutathione peroxidase (GPX)

GPX activity was measured by observing the change in absorbance at 470 nm. The reaction mixture consisted of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with 0.1 mM EDTA, 5 mM guaiacol, 15 mM H₂O₂, and 50 µL of enzyme extract. A tetra guaiacol extinction coefficient of 26.6 mM⁻¹ cm⁻¹ was used for the calculations75.

Superoxide dismutase activity (SOD)

Superoxide dismutase activity was measured photometrically using Beyer and Fridovich’s, 198776. The assay mixture consisted of 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.8), 0.1 mM EDTA, 12 mM methionine, 75 µM nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), and 0.025% Triton X-100. Each cuvette received 2.9 mL of the buffer and 5 µL of 2 µM riboflavin, with absorbance measured at 560 nm. Using 100 µL of enzyme extract per sample, the cuvettes were exposed to a 60-watt fluorescent light for 30 min, with absorbance checked every 5 min to find a stable reading. Enzyme activity was calculated using the percentage inhibition formula: (Absorption without enzyme / 100) × (Absorption with enzyme - Absorption without enzyme), multiplied by 50/1000 mg Protein.

Statistical analysis

Following normality and homogeneity of variance tests (Bartlett’s and Levene’s tests) which indicated no evidence of non-homogeneity of variance across the two years, and a normal distribution of the data, a combined ANOVA was performed, with the year treated as a fixed effect. Since the effect of the year was significant for some measured indices, the results for the two years are presented separately. Mean comparisons were conducted using the protected least significant difference (LSD) test. The entire data analysis was performed using RStudio v4.3.2 software (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria). To categorize all treatments, we conducted heatmap and cluster analyses using the gplots, dendextend, and d3heatmap R packages. Additionally, correlation analysis was carried out using the PCA function from the prcomp package.

Data availability

The data set used and/or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.The datasets of Bacillus velezensis UTB96 during the current study are available in the NCBI repository, (The complete genome sequence of B. velezensis UTB96 has been deposited under the GenBank accession number KY992857. The raw read data are available at the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under SRA accession number SRX5559694).

References

Pujolà, M., Farreras, A. & Casañas, F. Protein and starch content of raw, soaked and cooked beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L). Food Chem. 102 (4), 1034–1041 (2007).

Rubiales, D. & Mikić, A. Introduction: legumes in sustainable agriculture. Crit. Rev. Plant. Sci. 34, 2–3 (2015).

Subramani, M. et al. Comprehensive Proteomic Analysis of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Seeds Reveal Shared and Unique Proteins Involved in Terminal Drought stress response in tolerant and sensitive genotypes. Biomolecules. 14 (1), 109 (2024).

Loboguerrero, A. M. et al. Food and Earth Systems: priorities for Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation for Agriculture and Food systems. Sustainability. 11, 1372 (2019).

Rastgordani, F. et al. Climate change impact on herbicide efficacy: a model to predict herbicide dose in common bean under different moisture and temperature conditions. Crop Prot. 163, 106097 (2023).

Martínez, J. P. et al. Effect of drought stress on the osmotic adjustment, cell wall elasticity and cell volume of six cultivars of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L). Eur. J. Agron. 26, 30–38 (2007).

Batool, T. et al. Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria alleviates drought stress in potato in response to suppressive oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes activities. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 16975 (2020).

Ji, X. et al. Importance of pre-anthesis anther sink strength for maintenance of grain number during reproductive stage water stress in wheat. Plant. Cell. Environ. 33 (6), 926–942 (2010).

Powell, N. et al. Yield stability for cereals in a changing climate. Funct. Plant. Biol. 39, 539–552 (2012).

Singh, M. et al. Sulphur alters chromium (VI) toxicity in Solanum melongena seedlings: role of sulphur assimilation and sulphur-containing antioxidants. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 112, 183–192 (2017).

Gill, S. S. & Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 48, 909–930 (2010).

Gharib, F. A. E. L. et al. Impact of Chlorella vulgaris, Nannochloropsis salina, and Arthrospira platensis as bio-stimulants on common bean plant growth, yield and antioxidant capacity. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 1398 (2024).

Abd, E. et al. Glutathione-mediated changes in productivity, photosynthetic efficiency, osmolytes, and antioxidant capacity of common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) grown under water deficit. PeerJ. 11, e15343 (2023).

Gontia-Mishra, I. et al. Amelioration of drought tolerance in wheat by the interaction of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Plant. Biol. 18 (6), 992–1000 (2016).

Khan, N. et al. Comparative physiological and metabolic analysis reveals a complex mechanism involved in drought tolerance in chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) induced by PGPR and PGRs. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 2097 (2019).

Khan, N. & Bano, A. Exopolysaccharide producing rhizobacteria and their impact on growth and drought tolerance of wheat grown under rainfed conditions. PLoS One 14(9), e0222302 (2019).

Moretti, L. G. et al. Beneficial microbial species and metabolites alleviate soybean oxidative damage and increase grain yield during short dry spells. Eur. J. Agron. 127, 126293 (2021).

AbdelMotlb, N. A. et al. Rhizobium enhanced drought stress tolerance in green bean plants through improving physiological and biochemical biomarkers. Egypt. J. Hortic. 50 (2), 231–245 (2023).

Ojuederie, O. B. et al. Plant growth promoting rhizobacterial mitigation of drought stress in crop plants: implications for sustainable agriculture. Agronomy. 9 (11), 712 (2019).

Sansinenea, E. Bacillus spp.: As plant growth-promoting bacteria. In Secondary metabolites of plant growth promoting rhizo microorganisms: Discovery and applications, 225–237 (2019).

Gagné-Bourque, F. et al. Accelerated growth rate and increased drought stress resilience of the model grass Brachypodium distachyon colonized by Bacillus subtilis B26. PLoS ONE. 10, e0130456. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130456 (2015).

Bagheri, N. et al. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens UTB96, an effective biocontrol and aflatoxin-degrading bacterium. BioControl Plant. Prot. 6 (1), 1–17 (2018).

Vahidinasab, M. et al. Bacillus velezensis UTB96 is an antifungal soil isolate with a reduced genome size compared to that of Bacillus velezensis FZB42. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 8 (38), 10–1128 (2019).

Kenfaoui, J. Bacillus velezensis: a versatile ally in the battle against phytopathogens—insights and prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 108 (1), 439 (2024).

Munir, M. et al. Improving okra productivity by mitigating drought through foliar application of salicylic acid. Pak J. Agric. Sci. 53, 879–884. https://doi.org/10.21162/PAKJAS/16.4928 (2016).

Beigzadeh, S. et al. Ecological and physiological performance of white bean Phaseolus vulgaris L affected by algae extract and salicylic acid spraying under water deficit stress. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 17, 343–355. https://doi.org/10.15666/aeer/1701_343355 (2019).

Khan, M. I. R. et al. Alleviation of salt-induced photosynthesis and growth inhibition by salicylic acid involves glycinebetaine and ethylene in mungbean (Vigna radiata L). Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 80, 67–74 (2014).

Naeem, M. et al. Effect of salicylic acid and salinity stress on the performance of tomato plants. Gesunde Pflanz. 72, 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10343-020-00521-7 (2020).

Saidi, I. et al. Oxidative damage induced by short-term exposure to cadmium in bean plants: protective role of salicylic acid. S Afr. J. Bot. 85, 32–38 (2013).

Mehrasa, H. et al. Endophytic bacteria and SA application improve growth, biochemical properties, and nutrient uptake in white beans under drought stress. J. Soil. Sci. Plant. Nutr. 22 (3), 3268–3279 (2022).

Senaratna, T. et al. Acetyl salicylic acid (aspirin) and salicylic acid induce multiple stress tolerance in bean and tomato plants. Plant. Growth Regul. 30 (2), 157–161 (2000).

Papathanasiou, F. et al. The evaluation of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes under water stress based on physiological and agronomic parameters. Plants. 11 (18), 2432 (2022).

Mathobo, R. et al. The effect of drought stress on yield, leaf gaseous exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L). Agric. Water Manag. 180, 118–125 (2017).

Lizana, C. et al. Differential adaptation of two varieties of common bean to abiotic stress: I. effects of drought on yield and photosynthesis. J. Exp. Bot. 57 (3), 685–697 (2006).

López-Ruiz, B. A. et al. Interplay between hormones and several abiotic stress conditions on Arabidopsis thaliana primary root development. Cells. 9 (12), 2576 (2020).

Rehman, H. M. et al. Legume biofortification is an underexploited strategy for combatting hidden hunger. Plant. Cell. Environ. 42 (1), 52–70 (2019).

Evers, D. et al. Identification of drought-responsive compounds in potato through a combined transcriptomic and targeted metabolite approach. J. Exp. Bot. 61 (9), 2327–2343 (2010).

FAO. Crop Prospects and Food Situation. Food and Agriculture Organization, Global Information and Early Warning System (Trade and Markets Division (EST), 2015).

Lulsdorf, M. M. et al. Endogenous hormone profiles during early seed development of C. Arietinum and C. Anatolicum. Plant. Growth Regul. 71, 191–198 (2013).

Monneveux, P. et al. Drought tolerance in potato (S. Tuberosum L.): can we learn from drought tolerance research in cereals? Plant. Sci. 205, 76–86 (2013).

Mahajan, S. & Tuteja, N. Cold, salinity and drought stresses: an overview. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 444 (2), 139–158 (2005).

Saneoka, H. et al. Nitrogen nutrition and water stress effects on cell membrane stability and leaf water relations in Agrostis palustris huds. Environ. Exp. Bot. 52 (2), 131–138 (2004).

Islam, S. et al. Salicylic acid application mitigates oxidative damage and improves the growth performance of Barley under Drought stress. Phyton (0031-9457), 92(5) (2023).

Bouremani, N. et al. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): a rampart against the adverse effects of drought stress. Water 15(3), 418 .

Luo, Y. L. et al. Salicylic acid improves chilling tolerance by affecting antioxidant enzymes and osmo regulators in Sacha Inchi (Plukenetia Volubilis). Braz J. Bot. 37, 357–363 (2014).

La, V. H. et al. Salicylic acid improves drought-stress tolerance by regulating the redox status and proline metabolism in Brassica rapa. Hort Environ. Biotechnol. 60, 31–40 (2019).

Estaji, A. & Niknam, F. Foliar salicylic acid spraying effect on growth, seed oil content, and physiology of drought stressed Silybum marianum L. plant. Agric. Water Manag. 234, 106116 (2020).

Abid, M. et al. Improved tolerance to post-anthesis drought stress by pre-drought priming at vegetative stages in drought-tolerant and-sensitive wheat cultivars. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 106, 218–227 (2016).

Banik, P. et al. Effects of drought acclimation on drought stress resistance in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) genotypes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 126, 76–89 (2016).

Hageman, A. & Van Volkenburgh, E. Sink strength maintenance underlies drought tolerance in common bean. Plants. 10, 489 (2021).

Keller, I. et al. Improved resource allocation and stabilization of yield under abiotic stress. J. Plant. Physiol. 257, 153336 (2021).

Celi, G. et al. Physiological and biochemical roles of ascorbic acid on mitigation of abiotic stresses in plants. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 107970 (2023).

Zia, R. et al. Plant survival under drought stress: implications, adaptive responses, and integrated rhizosphere management strategy for stress mitigation. Microbiol. Res. 242, 126626 (2021).

Naher, J. et al. Heat stress modulates superoxide and hydrogen peroxide dismutation and starch synthesis during tuber development in potato. Am. J. Potato Res. 1–15 (2024).

Desoky, E. S. M. et al. Physio-biochemical and agronomic responses of faba beans to exogenously applied nano-silicon under drought stress conditions. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 637783 (2021).

Ali, F. et al. Recent methods of drought stress tolerance in plants. Plant. Growth Regul. 82, 363–375 (2017).

Abobatta, W. F. Drought adaptive mechanisms of plants—A review. Adv. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2, 62–65 (2019).

Gabr, M. E. Modelling net irrigation water requirements using FAO CROPWAT 8.0 and CLIMWAT 2.0: a case study of Tina Plain and East South ElKantara regions, North Sinai. Egypt. Arch. Agron. Soil. Sci. 1–16 (2021).

Chauhdary, J. N. et al. Improving corn production by adopting efficient fertigation practices: experimental and modeling approach. Agric. Water Manag. 221, 449–461 (2019).

Allen, R. G. et al. Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements-FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. FAO, Rome 300, D05109 (1998).

Skogerboe, G. V. et al. Selection and installation of cutthroat flumes for measuring irrigation and drainage water. Ann. Bot. 96 (6), 1129–1136 (1973).

Cavalcante, A. G. et al. Thermal sum and phenological descriptions of growth stages of the common bean according to the BBCH scale. Ann. Appl. Biol. 176 (3), 342–349 (2020).

Afsharmanesh, H. & Ahmadzadeh, M. The iturin lipopeptides as key compounds in antagonism of Bacillus subtilis UTB96 toward Aspergillus Flavus. Biol. Control Pest Plant. Dis. 5, 79–95 (2016).

Vahidinasab, M. et al. Characterization of Bacillus velezensis UTB96, demonstrating improved lipopeptide production compared to the strain B. Velezensis FZB42. Microorganisms. 10 (11), 2225 (2022).

Sasani et al. Bio-priming of seeds with Bacillus Velezensis UTB96 for controlling the fungal pathogen of root and crown rot (Fusarium pseudograminearum) and improving some growth indices of wheat. Iran. J. Seed Sci. Technol. 10 (4), 85–102 (2021).

Barrs, H. D. & Weatherley, P. E. A re-examination of the relative turgidity technique for estimating water deficits in leaves. Aust J. Biol. Sci. 15 (3), 413–428 (1962).

Ye, X. et al. Magnesium-deficiency effects on pigments, photosynthesis and photosynthetic electron transport of leaves, and nutrients of leaf blades and veins in Citrus sinensis seedlings. Plants. 8 (10), 389 (2019).

Predieri, S. et al. Influence of UV-B radiation on membrane lipid composition and ethylene evolution in ‘Doyenne D’hiver’ pear shoots grown in vitro under different photosynthetic photon fluxes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 35 (2), 151–160 (1995).

Velikova, V. et al. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant. Sci. 151 (1), 5966 (2000).

Schlegel, H. G. Die verwertung organischer säuren durch Chlorella im licht. Planta. 47, 510–526 (1956).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72 (1–2), 248–254 (1976).

Bates, L. S. et al. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant. Soil. 39, 205–207 (1973).

Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 22, 867–280 (1981).

Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. In Methods in Enzymology, Vol. 105, 121–126 (Academic, (1984).

Urbanek, H. et al. Elicitation of defence responses in bean leaves by Botrytis cinerea polygalacturonase.

Beyer, W. F. Jr & Fridovich, I. Assaying for superoxide dismutase activity: some large consequences of minor changes in conditions. Anal. Biochem. 161 (2), 559–566 (1987).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not Funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.Z. performed the field trials, conducted laboratory experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the draft version of the manuscript. N.MH. and M.O. proposed the idea, provided the plant materials, laboratory facilities, and instruments, and were involved in designing the experiment. K.A. assisted in the field trials. E.R. was involved in data analysis. Z.T. contributed to the laboratory work. D.R. revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All required permits have been received from University of Tehran.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zamani, F., Hosseini, N.M., Oveisi, M. et al. Rhizobacteria and Phytohormonal interactions increase Drought Tolerance in Phaseolus vulgaris through enhanced physiological and biochemical efficiency. Sci Rep 14, 30761 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79422-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79422-y