Abstract

Reliable predictions of concrete strength can reduce construction time and labor costs, providing strong support for building construction quality inspection. To enhance the accuracy of concrete strength prediction, this paper introduces an interpretable framework for machine learning (ML) models to predict the compressive strength of high-performance concrete (HPC). By leveraging information from a concrete dataset, an additional six features were added as inputs in the training process of the random forest (RF), AdaBoost, XGBoost and LightGBM models, and the optimal hyperparameters of the models were determined using 5-fold cross-validation and random search methods. Four interpretable ML models for predicting the compressive strength of HPC, including the RF, AdaBoost, XGBoost and LightGBM models, which combine feature derivation and random search, were constructed. In addition, the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method was applied to analyze the effects of the input features on the prediction results of the LightGBM model, which combines feature derivation and random search. The results showed that input features such as age, water/cement ratio, slag, and water were the key influences for predicting the compressive strength of HPC. Input features such as the superplastic/cement ratio, slag/cement ratio, and ash/cement ratio had nonsignificant impacts on the predicted compressive strength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High-performance concrete (HPC) is a construction material that is composed of coarse aggregates (such as gravel), fine aggregates (such as sand), and bonding materials (such as cement and water). Moreover, HPC exhibits excellent compressive strength, plasticity and durability, making it widely used in the construction of houses, roads, and bridges1,2. The compressive strength of HPC is a key performance indicator. Insufficient compressive strength reduces the durability of buildings, affects the safety of building structures and even causes casualties. For example, on May 21, 2023, a nine-story self-built house in Hunan, China, collapsed due to the inadequate compressive strength of the concrete and masonry mortar used in its construction, which were far below the national standard. In addition, the poor construction quality, irrational structural design, and low load-bearing capacity resulted in a total of 54 deaths, 9 injuries, and a direct economic loss of up to 90,778,600 yuan. Therefore, an accurate and convenient understanding of the compressive strength of HPC is highly important for project construction.

In engineering practice, determining the strength of HPC is largely based on empirical experiments. Usually, construction personnel use instruments to measure the compressive strength of concrete with different proportions within a certain period to determine the compressive strength3. However, this type of experiment has several disadvantages, including high labor costs, large manual errors, and long processing times. Therefore, during the initial stages of a project, on the basis of the existing input and output data of concrete, a robust and reliable predictive model for concrete compressive strength can be established. This model would help reduce the cost of compressive strength detection and shorten the detection cycle, effectively improving the quality and efficiency of project construction. In addition, early-stage prediction of concrete strength can provide the basis for construction safety assessment, structural health status diagnosis, and dynamic detection of structural strength. However, in the process of predicting HPC strength, there exists a nonlinear relationship between the input concrete data and the specific strength. Establishing a one-to-one mapping relationship is difficult. Therefore, creating an accurate predictive model for HPC strength to guide engineering practice is extremely important and remains a challenging research hotspot.

In recent years, with the development of artificial intelligence technology, researchers have developed many ML-based regression prediction models and applied them to the study of material performance4,5,6,7,8,9. For example, the support vector machine (SVM)10,11, decision tree12, random forest (RF)13,14,15,16, and K-nearest neighbors17 ML models have been used for predicting the compressive strength of concrete. Ouyang et al.18 proposed an artificial neural network algorithm to predict compressive strength. Mengxi Zhang et al.19 proposed a decision regression tree algorithm to predict compressive strength. In addition, Marani et al. used three ML models—RF, extremely random trees, and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost)—to predict compressive strength20. Xueqing Zhang et al.21 used nine ML methods, including linear, nonlinear and ensemble learning models, to predict the 7-day compressive strength of concrete. Hamdi et al.22 constructed an efficient concrete strength prediction hybrid model using a support vector machine and a genetic algorithm (SVM-GA).

The ultimate goal of the forecast models constructed in the above studies is to minimize the forecast error. Moreover, employing feature engineering and optimizing ML model hyperparameters can effectively reduce the forecasting errors of these models. Feature engineering methods are used to analyze and select an original dataset, effectively use the information, select the feature quantities that can best represent the performance of the sample, reasonably map the objective patterns of the sample, and ensure the accuracy and reliability of the prediction results23,24,25. For example, Xiaoning Cui et al.26 employed the feature recombination method to construct 10 datasets for data augmentation, thereby improving the utilization rate of concrete compressive strength data and the generalizability of the ML model. Fangming Deng et al.27 trained a regression model by using the deep features of the water/cement ratio, recycled coarse aggregate replacement rate, recycled fine aggregate replacement rate, fly ash content, and their combinations to improve the model accuracy. Ziyue Zeng et al.3 applied a deep convolutional neural network to predict compressive strength, and model input features were added on the basis of the feature derivation method. The above prediction models, which combine feature engineering and machine learning methods, have demonstrated good prediction accuracy, but there is still a need to incorporate more diverse interpretable features into prediction models28,29,30,31,32,33. For example, input features such as thermal properties34, strain rates35, soft-mode parameters36, and others could be considered, with the HPC as a basis for prediction. The performance of the HPC compressive strength prediction model can be further enhanced by screening features from the perspectives of microstructural evolution during curing and loading37,38, interactions between chemical composition and mechanical properties39, and nonmonotonic aging40,41.

The optimization algorithm mainly determines the optimal hyperparameters of the ML model, thereby improving the prediction accuracy of the model42,43,44. Yimiao Huang et al.45 used the SVM regression model to forecast the uniaxial compressive strength and flexural strength of concrete, and the hyperparameters of the SVM model were optimized and adjusted via the firefly algorithm (FA). A sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the significance of input features on the output variables. Qing-Fu Li et al.46 used four ML models: AdaBoost, gradient-boosted decision trees (GBDTs), XGBoost and RF. The optimal parameters for these models were obtained via the grid search method, and the optimal strength prediction performance of the four models was determined. Hoang Nguyen et al.2 used four ML methods to predict the compressive and tensile strengths of concrete, and a random search algorithm was applied to determine the best model parameters.

However, the abovementioned studies on HPC strength prediction fail to explain the black-box nature of ML models in compressive strength prediction10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,26,27,45,46. Understanding the interpretability of ML models is crucial for gaining deeper insights into their decision-making processes and the importance of feature variables. These insights are also important for improving and optimizing engineering practice and enhancing the credibility and transparency of ML models. The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) method serves as an approach for explaining ML models by attributing the prediction results of the model to specific features, thereby increasing the interpretability of predictive models47,48,49,50. Therefore, applying SHAP analysis can improve the applicability and reliability of prediction models for HPC compressive strength, which is of great practical significance for engineering construction.

To this end, this study introduces a framework for ML models that can accurately predict the compressive strength of HPC. By using concrete dataset information, additional input features were added to the training process of the ML model, 5-fold cross-validation was applied, and the optimal hyperparameters of the models were obtained via a random search method. Four interpretable ML models for predicting the compressive strength of HPC were constructed to analyze the effects of input parameters on the compressive strength of concrete and the interactions between dataset features.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

Six features were obtained. Fivefold cross-validation and random search methods were applied, and an ML model framework for accurately predicting the compressive strength of HPC was proposed.

-

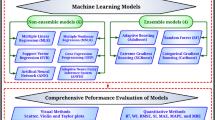

An interpretable model for HPC compressive strength using FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, FR_XGBoost and FR_LightGBM was constructed, and the evaluation was performed using four performance indicators, namely, the root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), mean absolute error (MAE), and coefficient of determination (R2), demonstrating the superiority of the FR_LightGBM prediction model.

-

The SHAP method was used to analyze the influence of the input features on the prediction results of the FR_LightGBM model.

The main content of this paper is as follows. In Section “Interpretable ML model for HPC compressive strength prediction”, four ML models, RF, AdaBoost, XGBoost and LightGBM, are introduced, and an interpretable ML model is proposed to accurately predict the compressive strength of HPC. In Section “Concrete dataset and feature engineering”, the analysis of the HPC dataset and the feature engineering method are presented. In Section “Model optimization and evaluation indicators”, optimization methods and evaluation indicators are proposed for four ML models. In Section “Experimental results”, the experimental results are analyzed, and an explanatory analysis of the optimal model is performed. Section “Conclusions” presents the conclusion.

Interpretable ML model for HPC compressive strength prediction

Basic principles of ML models

RF

RF51,52,53 is an ensemble learning algorithm based on a regression tree model. Multiple regression trees are formed via random sampling, and the results of the regression tree operations are subsequently combined to obtain the prediction results. The RF method selects the optimal features from the subspace of the total feature set, ensuring the independence and diversity of each decision tree, thus avoiding overfitting to a certain extent. The generalizability of the regression tree model is enhanced by the application of the bagging algorithm and the random eigenvalue subspace approach. The parameters that affect the predictive ability of the RF regression model are the number of decision tree models, the maximum number of features at the node and the maximum depth of the tree.

AdaBoost

AdaBoost54,55 is a popular meta-algorithm. The primary goal of AdaBoost is to generate and then aggregate a series of weak learners to form a strong learner. The main principle of the algorithm is as follows.

The training samples are defined as \(\left\{ {{x_i},{y_i}} \right\}_{{i=1}}^{n}\), and the output regressor variable is denoted as \(G(x)\). The weight of the sample is represented as \({D_t}\). After t iterations, the formula for calculating the maximum error for the training set is

The relative error of the i-th sample is

where \({y_i}\) is the true value of the sample and \({G_t}({x_i})\) is a weak learner with t iterations.

The formula of \({D_{t+1}}\) is obtained after \(t+1\) iterations as follows:

where \({Z_t}\) is the normalization constant.

All weak learners are integrated, and the formula of the strong learner is

where \({\alpha _t}\) is the weight coefficient and where \(g(x)\) is the weighted median value of all weak learners.

XGBoost

XGBoost56 is as an efficient implementation of the gradient boosting regression tree (GBRT) approach. It employs second-order Taylor expansion of the loss function to optimize the computational process and introduces a regularization term into the objective function. These improvements greatly increase the scalability and training speed of the model, enabling XGBoost to achieve excellent performance in the field of regression prediction57. The core strategy of the algorithm is to construct an additive model iteratively, step by step, aiming to minimize a differentiable loss function. XGBoost combines the advantages of a tree model with those of a linear model and continuously introduces new models in an iterative manner to correct the prediction bias from the previous round. On the basis of the principle of gradient boosting, the formula for the sample predicted value \(\hat {y}_{i}^{{(n)}}\) for the nth tree is shown below:

where \(\hat {y}_{i}^{{(t)}}\) is the prediction result of sample i after n iterations, \({f_t}({x_i})\) is the model of the nth tree to be trained, and \(\hat {y}_{i}^{{(t - 1)}}\) is the prediction result of the previous n-1 trees.

LightGBM

LightGBM58 is a state-of-the-art gradient boosting algorithm with fast training speed, high prediction accuracy, and good generalizability. As an enhanced gradient boosting method, LightGBM trains each subsequent weak learner (i.e., classification and regression tree (CART)) by fitting the residual gradient of the previous weak learner instead of training the subsequent weak learner with the weight-adjusted samples. By employing a gradient-based one-sided sampling method during the training process, samples with large gradients can be selected, while samples with small gradients can be ignored. At the same time, LightGBM segments the data by choosing the leaf with the highest information gain instead of segmenting the leaves on the same layer at the same time. The leaf algorithm tends to select the leaf with the largest loss difference. The training samples are set to \(\left\{ {{x_i},{y_i}} \right\}_{{i=1}}^{n}\), and the gradient boosting decision tree is \(f(x)\). The estimate is a series of decision trees \({h_t}(x)\). The sum of the results of the LightGBM model can be expressed as:

where \(T\) is the number of decision trees.

Interpretable ML model for HPC compressive strength prediction

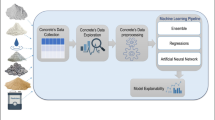

The overall framework of the interpretable ML model for predicting HPC compressive strength is illustrated in Fig. 1. This framework is divided into four main modules: data provision, feature selection, model execution, and performance evaluation.

HPC compressive strength data samples were collected and collated to provide basic data for subsequent strength prediction and optimization, serving as the foundation for the entire ML framework. The databases were screened, and an HPC compressive strength dataset was found, providing the original data for training the prediction model.

Based on the data provision module, feature derivation was applied to the original datasets. Six additional features, including the water/cement ratio, coarse/fine aggregate ratio, aggregate/cement ratio, ash/cement ratio, slag/cement ratio, and superplastic/cement ratio, were derived from the original data. The Pearson correlation coefficient method was used to analyze the correlation between the additional features and the predicted target, and the derived dataset was input into the model.

In the model execution module, the HPC prediction models were trained and tested. Through dataset feature derivation, 5-fold cross-validation and random search methods, four models for predicting the compressive strength of HPC, the RF model that combines feature derivation and random search (FR_RF), the AdaBoost model that combines feature derivation and random search (FR_AdaBoost), the XGBoost model that combines feature derivation and random search (FR_XGBoost) and the LightGBM model that combines feature derivation and random search (FR_LightGBM), were proposed. 80% of the HPC dataset was used for training. The optimal hyperparameters of the four ML models were determined, and the remaining 20% of the HPC dataset was used for testing and validation. The compressive strength prediction performance between the ML models were compared and analyzed.

In the performance evaluation module, the compressive strength of HPC was evaluated and interpreted. The prediction results of four models, FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, FR_XGBoost and FR_LightGBM, were analyzed and evaluated to determine the performance of the models in terms of predicting the compressive strength of HPC. Evaluation indicators were used to verify the practicality of the four ML models proposed in this paper. The SHAP method was used to interpret the ML models in terms of predicting the compressive strength of HPC, identifying the effect of input features on the compressive strength of HPC, and screening the key influencing factors.

Concrete dataset and feature engineering

Datasets

An HPC compressive strength dataset was collected from the UCI database2. This dataset includes a total of 1030 samples. The distribution of values in this dataset is shown in Fig. 2. To extract more information regarding the correlation between all the features (X) and targets (Y), the Pearson correlation coefficient method was used to calculate the correlation coefficient, and the formula is shown below:

where \(\rho\) is the Pearson correlation coefficient, \(X\) represents the features, \(Y\) represents the targets, \(\bar {X}\) and \(\bar {Y}\) represent the mean values, and the subscript \(i\) represents the i-th observed value.

Equation (7) ensures that the value of the coefficient \(\rho\) lies within the range [-1, 1]. A value of 0 represents no correlation between the specific features, a value of 1 represents a complete positive correlation, and a value of -1 represents a complete negative correlation. A correlation closer to -1 or 1 indicates that a stronger correlation between features, with a greater influence on the prediction result.

The statistical correlations between the features (X) and targets (Y) of the datasets are shown in Fig. 3. The results suggest that the cement feature has the strongest correlation with the compressive strength, with a correlation coefficient of 0.5. The superplasticizer, age, and water features had moderate correlations with compressive strength, with correlation coefficients of 0.37, 0.33, and − 0.29, respectively. In addition, there was a weak correlation between the compressive strength of the fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, slag and ash, with correlation coefficients of -0.17, -0.16, 0.13, and − 0.11, respectively.

Feature engineering

The generation of additional features was considered as a facet of data preprocessing. Expanding input features on the basis of established material science principles leads to better trained models31. Among these principles, Abram’s law reveals the importance of water–cement ratio in concrete. Reasonable adjustments to the water-cement ratio ensure that the concrete meets the strength requirements while maintaining good durability and construction performance to protect the quality and safety of the project59. The coarse–fine aggregate ratio is a key factor in the good performance of HPC in terms of workability, densification, and reduction in the void ratio60. In addition, the aggregate-to-cement ratio is an important factor affecting the mechanical properties of concrete blocks61. Bijen et al.62 explored the effect of the ash/cement ratio on the compressive strength of concrete. The slag/cement ratio is a significant factor affecting the workability of concrete63. In addition, the superplastic/cement ratio3 is considered in this paper.

During the training process of this study, six additional features were added to train the high-performance concrete compressive strength prediction model: the water/cement ratio, the coarse/fine aggregate ratio, the aggregate/cement ratio, the ash/cement ratio, the slag/cement ratio, and the superplastic/cement ratio. Table 2 shows the data statistics of the derived features. Table 1 lists the statistical results of the derived features.

Figure 4 shows the feature correlation matrix of Dataset 1 after the above features were derived. The water/cement ratio and aggregate/cement ratio were strongly correlated with the compressive strength, with coefficients of -0.5 and − 0.48, respectively. The ash/cement ratio and superplastic/cement ratio were moderately correlated with the compressive strength, with coefficients of -0.18 and 0.12, respectively. The coarse/fine aggregate ratio and slag/cement ratio were weakly correlated with the compressive strength, with correlation coefficients of 0.049 and − 0.069, respectively. These results indicate that the derived features of the dataset have a strong correlation with the target (Y), and the feature derivation methods can make full use of the feature information of the original dataset.

Before data are input into an ML model, the Z score normalization process should be performed with the dataset. The aim of Z score standardization is to prevent the weight of the trained model from being too small to cause instability in the numerical calculation and to enable the parameter optimization approach to converge at a faster speed.

The Z score normalization formula is as follows:

where \(\mu\) is the mean value of dataset \(x\), \(\sigma\) is the standard deviation of the dataset elements, and \(x^{\prime}\) is the result after \(x\) normalization and tends to follow a standard normal distribution.

Model optimization and evaluation indicators

Optimizing model hyperparameters

This study employed K-fold cross-validation with K = 5 to avoid random sampling bias. Figure 5 shows a schematic diagram of the 5-fold cross-validation method. As shown in this figure, the training set was divided into five parts, with four parts used as training data and one part used as validation data to test the experimental training effect of the model. The method can be applied to estimate the range of approximate values of the model hyperparameters.

The grid search method has been used most frequently in hyperparametric optimization. When applied, the method explores all the candidate parameter combinations and selects the hyperparameters that make the model perform optimally. Nevertheless, the drawbacks of grid search are readily apparent; that is, its running speed is relatively slow, and its efficiency is lower than that when the parameter space is large. The purpose of a random search is to randomly test several possible parameter combinations to find the optimal combination. A random search can reduce the training time of the forecasting model and improve the computational efficiency. In addition, a random search is more efficient than a grid search. In this paper, the random search algorithm was chosen as the search algorithm to find the optimal hyperparameters of the ML model.

Evaluation indicators for the ML models

To evaluate the capability of the ML model proposed in this research, four indicators were considered, including the RMSE, MAPE, MAE and R2. These evaluation metrics are calculated as follows:

where \({y_i}\) and \({\hat {y}_i}\) are the actual and predicted values, respectively. \(\bar {y}\) represents the mean value of the actual values, \(n\) represents the number of test data samples, and \(i\) represents the \(i\)th sample.

Experimental results

Performance of the ML model

The HPC compressive strength dataset was used to train four independent ML models, FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, FR_XGBoost and FR_LightGBM, and the hyperparameters of each ML model were randomly searched to determine the model with the best performance.

The hyperparameter spaces defined for the four ML models are as follows:

The hyperparameter space for FR_RF is as follows: n_estimators \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3, …, 1000}; max depth \(\:\in\:\) {0, 1, 2, …, 50}; min_impurity_decrease \(\:\in\:\) {0,1,2,3,4,5}; and max_features {“log2”, “sqrt”, 2, 4, 6,“auto”}. min_i_d is the abbreviation for min_impurity_decrease.

The hyperparameter space for FR_AdaBoost is as follows: n_estimators \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3, …, 100}; learning_rate \(\:\in\:\) {0.05, 0.1, 0.15, …, 1}; and loss \(\:\in\:\) {‘linear’, ‘square’, ‘exponential’}.

The hyperparameter space for FR_XGBoost is as follows: n_estimators \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3, …, 200}; max_bin \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3,…,100}; learning_rate \(\:\in\:\) {0.01, 0.02, 0.03, …, 0.3}; and n_estimators \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3, …, 50}.

The hyperparameter space for FR_LightGBM is as follows: max_depth \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3, …, 50}; num_leaves \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3,…,200}; max_bin \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3, …, 100}; and n_estimators \(\:\in\:\) {1, 2, 3, …, 200}.

The optimal hyperparameters determined through 5-fold cross-validation and a random search method for four interpretable ML models for predicting the compressive strength of HPC are shown in Table 2. The simulation results of the training set and validation set are shown in Table 3.

To compare and analyze the effects of the hyperparameters on the ML models, the RMSEs of FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost and FR_LightGBM were calculated under different hyperparameter configurations through multiple iterative experiments. Figure 6 shows the impact of n_estimators and max_depth on the RMSE of the FR_RF model. When n_estimators increased from 0 to 200 and max_depth increased from 0 to 5, the RMSE of the FR_RF prediction model decreased significantly. A reduction in the RMSE indicates that the model prediction error decreases. Figure 7 shows the impact n_estimators and learning_rate on the RMSE of the FR_AdaBoost model. When n_estimators increased between 30 and 80 and the learning_rate increased between 0.2 and 1, the performance of the AdaBoost model significantly improved. Figure 8 shows the impact of n_estimators and max_bin on the RMSE of the FR_XGBoost model. The results show that n_estimators had a small effect on the model performance, and max_bin in the range of 20–100 significantly improved the performance of the FR_XGBoost model. Figure 9 shows the impact of n_estimators and num_leaves on the RMSE of the FR_LightGBM model. A smaller num_leaves tended to increase error in LightGBM error, while n_estimators had a lesser impact on the model performance (Fig. 9).

To accurately evaluate and analyze the interpretability of the ML models for predicting HPC compressive strength proposed in this paper, the performance of the four models was evaluated. The test set prediction results for the four evaluation indicators, RMSE, MAPE, MAE, and R2, are shown in Table 4. In addition, for the same dataset, the results were compared with the results of models in other papers (Table 4).

The FR_RF model outperformed the SVR, GEP, M-GGP, ANN-SVR, and SFA-LSSVR models in terms of the RMSE and MAE. Compared with those of the original model, the RMSE and MAE of the FR_RF model decreased by 10.3% and 12.6%, respectively, the MAPE decreased by 1%, and the R2 increased by 1%. The prediction results of the FR_RF model with the test set are shown in Fig. 10a. Although FR_AdaBoost did not yield the best results, it outperformed the original model, and the overall performance of the FR_AdaBoost model was better than that of the M-GGP model. In this study, when the hyperparameters of the FR_AdaBoost model were n_estimators = 76 and learning_rate = 0.9, compared with those of the original model, the MAPE was the same, the MAE of the FR_AdaBoost model decreased by 6.5%, the R2 increased by 3.7%, and the RMSE decreased by 6.5%. The prediction results of the FR_AdaBoost model with the test set are shown in Fig. 10b.

The predicted values for the FR_XGBoost model test set are shown in Fig. 10c. The results are as follows: RMSE = 3.26, MAPE = 10%, MAE = 2.63, and R2 = 0.95. There was a 4.4% decrease in the RMSE relative to that of the original model. The FR_XGBoost model was better than FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, SVR, MLP, and GEP are in terms of the RMSE, MAPE, MAE and R2. This result indicates that the FR_XGBoost model has high accuracy in predicting the compressive strength of HPC.

In addition, the FR_LightGBM model outperformed the FR_XGBoost, FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, LightGBM, SVR, MLP, GEP, M-GGP, ANN-SVR and SFA-LSSVR models in terms of the RMSE, MAPE, MAE and R2. Compared with those of FR_XGBoost, the RMSE and MAE of the FR_LightGBM model were reduced by 11.1% and 10.6%, respectively, the MAPE was reduced by 1%, and the R2 improved by 1%. Compared with those of the FR_RF model, the RMSE and MAE of the FR_LightGBM model decreased by 21.4% and 24.1%, respectively, the MAPE decreased by 3%, and the R2 increased by 2.1%. Compared with those of the M-GGP model, the RMSE and MAE of the FR_LightGBM model decreased by 55.4% and 57.1%, respectively, and the R2 increased by 6.6%. Compared with those of the MLP model, the comprehensive performance of the FR_LightGBM model was better. The RMSE and MAE decreased by 24.8% and 20.0%, respectively, and the MAPE decreased by 0.8%. The predicted values of the FR_LightGBM model with the test set are shown in Fig. 10d. The results are as follows: RMSE = 3.26, MAPE = 9%, MAE = 2.35, and R2 = 0.96. Compared with those of the original model, the RMSE and MAE of the FR_LightGBM model decreased by 14.2% and 10.9%, respectively, the MAPE decreased by 1%, and the R2 increased by 1%. The comparison of the experimental results quantified by the indicators reveals that the FR_LightGBM model based on the proposed method achieved high precision in predicting the compressive strength of HPC.

The performance of the FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, FR_XGBoost and FR_LightGBM models are shown in Fig. 11. The performance of the FR_LightGBM model was better than that of the other two models, and the ranking of the prediction performance of the HPC compressive strength from high to low was FR_LightGBM, FR_XGBoost, FR_RF, and FR_AdaBoost.

Interpretive analysis

SHAP is a method of explaining ML models. The SHAP value indicates the relative influence and contribution of each input variable on the generation of the final output variable. Similar to the concept of parametric analysis, when one variable is changed, the other variables are kept constant to analyze the effect of the changed variable on the target attribute. In this section, the relative importance of each variable is discussed in terms of the HPC compressive strength, thus defining the effect of the input variables on the HPC compressive strength. In this paper, the optimal FR_LightGBM model is analyzed and explained.

Global analysis

The FR_LightGBM model was interpreted and analyzed via two global analysis methods. The first method involves the importance of the input features (Fig. 12). The feature importance values in Fig. 12 are calculated by averaging the SHAP values of the entire dataset. The features of age, water/cement ratio, slag, and water have significant impacts on concrete strength prediction. The addition of the aggregate/cement ratio, cement, superplasticizer, fine aggregate, coarse aggregate, ash, and coarse/fine aggregate ratio had a strong effect on the compressive strength of the concrete. The superplastic/cement ratio, slag/cement ratio, and ash/cement ratio had weak effects.

The second method involves examining the variation trend of the corresponding variables and the distribution of the SHAP value of a single feature (Fig. 13). The greater the eigentime value is, the greater the compressive strength of the concrete. Thus, the compressive strength of the concrete increases with time. A greater water/cement ratio, water content, aggregate/cement ratio, fine aggregate content, and ash/cement ratio had a negative impact on the compressive strength of the concrete. In contrast, a larger slag, cement, superplasticizer, coarse aggregate, ash, coarse/fine aggregate ratio, superplastic/cement ratio, and slag/cement ratio led to a greater increase in the compressive strength of the concrete.

Interpretation of a single feature

An interpretive analysis was conducted on a single sample to study the influence of each feature on the forecast results (Fig. 14). The features were sorted according to their importance, and the most important features were identified. The base value represents the average value of the concrete strength in the dataset, that is, 35.73 MPa. The red features (fine aggregate, slag, age, cement, aggregate/cement ratio, etc.) increase the compressive strength of the HPC above the base value, whereas the blue features (water/cement ratio, superplastic/cement ratio) decrease the compressive strength. Finally, under the joint action of all the features, the predicted bond strength was 43.33 MPa.

Among the key features, the bonding force between the fine aggregate and the interfacial structure is stronger, improving the compressive strength of the concrete. Slag refines the pore size of the concrete, improving its pore structure, compactness and compressive strength of the concrete. The compressive strength of HPC is closely related to its age, and with increasing age, the compressive strength of concrete gradually increases. The cement content has a decisive influence on the compressive strength of HPC. The aggregate-to-cement ratio affects the overall mechanical properties of concrete. The water/cement ratio has an inverse relationship with the HPC compressive strength, and the water/cement ratio directly affects the cement paste structure and porosity within the concrete. The dosage of the superplasticizer should not be too high, as excessive amounts can adversely affect the performance of the concrete.

In this single prediction, the fine aggregate, slag, age, cement, aggregate/cement ratio, and water/cement ratio were identified as the main features affecting the compressive strength of HPC.

Conclusions

To increase the prediction accuracy of the HPC compressive strength prediction model, an interpretable ML model framework was proposed. Four independent ML models, FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, FR_XGBoost and FR_LightGBM, were developed using this framework, and the performance of the prediction model was evaluated by considering the RMSE, MAPE, MAE and R2. The aim was to explain the black-box nature of the ML models and accurately determine the influence of features on HPC compressive strength prediction. In a follow-up study, we will consider the influence of data distortion and data drift in data collected from actual engineering applications to construct a concrete sample set by combining feature derivation and dimensionality reduction methods and using an ensemble model and a deep learning model with better performance. A strength prediction model for high-performance compressive concrete that is resistant to the influence of interference will be used to provide timely and effective strength prediction services for project construction. On the basis of the simulation analysis results, the following conclusions were reached:

-

(1)

Six feature parameters, namely, the water/cement ratio, coarse/fine aggregate ratio, aggregate/cement ratio, ash/cement ratio, slag/cement ratio and superplastic/cement ratio, were used to increase the number of features in the dataset. Four HPC compressive strength prediction models, FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost, FR_XGBoost and FR_LightGBM, were constructed using 5-fold cross-validation and random search methods. Compared with that of the original model, the performance of the HPC compressive strength prediction model significantly improved.

-

(2)

The FR_LightGBM model was superior to the FR_RF, FR_AdaBoost and FR_XGBoost models in terms of predicting the compressive strength of HPC, and the performance of the FR_LightGBM, FR_XGBoost, FR_RF and FR_AdaBoost models were ranked from highest to lowest. The RMSE, MAPE, MAE and R2 were 3.26, 9%, 2.35 and 0.96, respectively, for the FR_LightGBM model, 3.67, 10%, 2.63 and 0.95, respectively, for the FR_XGBoost model, 4.15, 12%, 3.10 and 0.94, respectively, for the FR_RF model, and 7.06, 27%, 5.88 and 0.83, respectively, for the FR_AdaBoost model.

-

(3)

The SHAP method was used to analyze the effects of the input features on the prediction results of the FR_LightGBM model. The results revealed that age, water/cement ratio, slag, and water features were the key influencing factors in predicting the compressive strength of HPC. Features such as the superplastic/cement ratio, slag/cement ratio, and ash/cement ratio had nonsignificant impacts on the prediction results.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Li, Z. et al. Machine learning in concrete science: Applications, challenges, and best practices. Npj Comput. Mater. 8, 127 (2022).

Nguyen, H., Vu, T., Vo, T. P. & Thai, H. T. Efficient machine learning models for prediction of concrete strengths. Constr. Build. Mater. 266, 120950 (2021).

Zeng, Z. et al. Accurate prediction of concrete compressive strength based on explainable features using deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 329, 127082 (2022).

Qian, P. et al. Tidal current prediction based on a hybrid machine learning method. Ocean Eng. 260, 111985 (2022).

Mintarya, L. N., Halim, J. N. M., Angie, C., Achmad, S. & Kurniawan, A. Machine learning approaches in stock market prediction: A systematic literature review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 216, 96–102 (2023).

Eyo, E. U. & Abbey, S. J. Machine learning regression and classification algorithms utilised for strength prediction of OPC/by-product materials improved soils. Constr. Build. Mater. 284, 122817 (2021).

Condemi, C., Casillas-Pérez, D., Mastroeni, L., Jiménez-Fernández, S. & Salcedo-Sanz, S. Hydro-power production capacity prediction based on machine learning regression techniques. Knowl. Based Syst. 222, 107012 (2021).

Çeli̇k, T. B., İcan, Ö. & Bulut, E. Extending machine learning prediction capabilities by explainable AI in financial time series prediction. Appl. Soft Comput. 132, 109876 (2023).

Abdelmoula, I. A., Elhamaoui, S., Elalani, O., Ghennioui, A. & Aroussi, M. E. A photovoltaic power prediction approach enhanced by feature engineering and stacked machine learning model. Energy Rep. 8, 1288–1300 (2022).

Lyu, F., Fan, X., Ding, F. & Chen, Z. Prediction of the axial compressive strength of circular concrete-filled steel tube columns using sine cosine algorithm-support vector regression. Compos. Struct. 273, 114282 (2021).

Safarzadegan Gilan, S., Bahrami Jovein, H. & Ramezanianpour, A. A. Hybrid support vector regression – particle swarm optimization for prediction of compressive strength and RCPT of concretes containing metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 34, 321–329 (2012).

Erdal, H. I. Two-level and hybrid ensembles of decision trees for high performance concrete compressive strength prediction. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 26, 1689–1697 (2013).

Pengcheng, L., Xianguo, W., Hongyu, C. & Tiemei, Z. Prediction of compressive strength of high-performance concrete by random forest algorithm. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 552, 012020 (2020).

Li, H., Lin, J., Lei, X. & Wei, T. Compressive strength prediction of basalt fiber reinforced concrete via random forest algorithm. Mater. Today Commun. 30, 103117 (2022).

Han, Q., Gui, C., Xu, J. & Lacidogna, G. A generalized method to predict the compressive strength of high-performance concrete by improved random forest algorithm. Constr. Build. Mater. 226, 734–742 (2019).

Farooq, F. et al. A comparative study of random forest and genetic engineering programming for the prediction of compressive strength of high strength concrete (HSC). Appl. Sci. 10, 7330 (2020).

Ghunimat, D., Alzoubi, A. E., Alzboon, A. & Hanandeh, S. Prediction of concrete compressive strength with GGBFS and fly ash using multilayer perceptron algorithm, random forest regression and k-nearest neighbor regression. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 24, 169–177 (2023).

Predicting Concrete’s Strength by Machine Learning: Balance between Accuracy and Complexity of Algorithms. MJ 117 (2020).

Zhang, M., Li, M., Shen, Y., Ren, Q. & Zhang, J. Multiple mechanical properties prediction of hydraulic concrete in the form of combined damming by experimental data mining. Constr. Build. Mater. 207, 661–671 (2019).

Marani, A. & Nehdi, M. L. Machine learning prediction of compressive strength for phase change materials integrated cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 265, 120286 (2020).

Zhang, X., Akber, M. Z. & Zheng, W. Prediction of seven-day compressive strength of field concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 305, 124604 (2021).

Al-Jamimi, H. A., Al-Kutti, W. A., Alwahaishi, S. & Alotaibi, K. S. Prediction of compressive strength in plain and blended cement concretes using a hybrid artificial intelligence model. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 17, e01238 (2022).

Yun, K. K., Yoon, S. W. & Won, D. Prediction of stock price direction using a hybrid GA-XGBoost algorithm with a three-stage feature engineering process. Expert Syst. Appl. 186, 115716 (2021).

Matuozzo, A., Yoo, P. D. & Provetti, A. A right kind of wrong: European equity market forecasting with custom feature engineering and loss functions. Expert Syst. Appl. 223, 119854 (2023).

Heaton, J. IEEE, Norfolk, VA, USA,. An empirical analysis of feature engineering for predictive modeling. In SoutheastCon 2016 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/SECON.2016.7506650 (2016).

Cui, X., Wang, Q., Zhang, R., Dai, J. & Li, S. Machine learning prediction of concrete compressive strength with data enhancement. IFS. 41, 7219–7228 (2021).

Deng, F. et al. Compressive strength prediction of recycled concrete based on deep learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 175, 562–569 (2018).

Li, X. T., Tang, X. Z., Fan, Y. & Guo, Y. F. The interstitial emission mechanism in a vanadium-based alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. (2020).

He, M., Yang, Y., Gao, F. & Fan, Y. Stress sensitivity origin of extended defects production under coupled irradiation and mechanical loading. Acta Mater. (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Concurrent prediction of metallic glasses’ global energy and internal structural heterogeneity by interpretable machine learning. Acta Mater. 259, 119281 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Predicting the energetics and kinetics of cr atoms in Fe–Ni–Cr alloys via physics-based machine learning. Scr. Mater. 205, 114177 (2021).

Jiang, L. et al. Deformation mechanisms in crystalline-amorphous high-entropy composite multilayers. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 848, 143144 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Nonmonotonic effect of chemical heterogeneity on interfacial crack growth at high-angle grain boundaries in Fe–Ni–Cr alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater. 7, 073606 (2023).

Bai, Z., Misra, A. & Fan, Y. Universal trend in the dynamic relaxations of tilted metastable grain boundaries during ultrafast thermal cycle. Mater. Res. Lett. 10, 343–351 (2022).

Tang, X. Z. et al. Strain rate effect on dislocation climb mechanism via self-interstitials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 713, 141–145 (2018).

Zhang, S., Liu, C., Fan, Y., Yang, Y. & Guan, P. Soft-mode parameter as an indicator for the activation energy spectra in metallic glass. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 2781–2787 (2020).

Wu, B. Atomistic mechanism and probability determination of the cutting of Guinier-Preston zones by edge dislocations in dilute Al-Cu alloys. Phys. Rev. Mater. (2020).

Bai, Z., Balbus, G. H., Gianola, D. S. & Fan, Y. Mapping the kinetic evolution of metastable grain boundaries under non-equilibrium processing. Acta Mater. 200, 328–337 (2020).

Li, X. T., Tang, X. Z., Guo, Y. F., Li, H. & Fan, Y. Modulating grain boundary-mediated plasticity of high-entropy alloys via chemo-mechanical coupling. Acta Mater. 258, 119228 (2023).

Liu, C., Yan, X., Sharma, P. & Fan, Y. Unraveling the non-monotonic ageing of metallic glasses in the metastability-temperature space. Comput. Mater. Sci. 172, 109347 (2020).

Wang, Y. & Fan, Y. Incident velocity induced nonmonotonic aging of vapor-deposited polymer glasses. J. Phys. Chem. B. 124, 5740–5745 (2020).

Qu, Z., Xu, J., Wang, Z., Chi, R. & Liu, H. Prediction of electricity generation from a combined cycle power plant based on a stacking ensemble and its hyperparameter optimization with a grid-search method. Energy. 227, 120309 (2021).

Liashchynskyi, P. & Liashchynskyi, P. Grid search, random search, geneticalgorithm: A big comparison for NAS. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1912.06059 (2019).

Florea, A. C. & Andonie, R. Weighted random search for hyperparameter optimization. Int. J. Comput. Commun. 14, 154–169 (2019).

Huang, Y., Zhang, J., Tze Ann, F. & Ma, G. Intelligent mixture design of steel fibre reinforced concrete using a support vector regression and firefly algorithm based multi-objective optimization model. Constr. Build. Mater. 260, 120457 (2020).

Li, Q. F. & Song, Z. M. High-performance concrete strength prediction based on ensemble learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 324, 126694 (2022).

Anjum, M. et al. Application of ensemble machine learning methods to estimate the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced nano-silica modified concrete. Polymers. 14, 3906 (2022).

Wang, X., Chen, A. & Liu, Y. Explainable ensemble learning model for predicting steel section-concrete bond strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 356, 129239 (2022).

Abdulalim Alabdullah, A. et al. Prediction of rapid chloride penetration resistance of metakaolin based high strength concrete using light GBM and XGBoost models by incorporating SHAP analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 345, 128296 (2022).

Ekanayake, I. U., Meddage, D. P. P. & Rathnayake, U. A novel approach to explain the black-box nature of machine learning in compressive strength predictions of concrete using Shapley additive explanations (SHAP). Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01059 (2022).

Zhang, J. et al. Modelling uniaxial compressive strength of lightweight self-compacting concrete using random forest regression. Constr. Build. Mater. 210, 713–719 (2019).

Suenaga, D., Takase, Y., Abe, T., Orita, G. & Ando, S. Prediction accuracy of Random Forest, XGBoost, LightGBM, and artificial neural network for shear resistance of post-installed anchors. Structures. 50, 1252–1263 (2023).

Li, Y., Li, H., Jin, C. & Shen, J. The study of effect of carbon nanotubes on the compressive strength of cement-based materials based on machine learning. Constr. Build. Mater. 358, 129435 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Computation of high-performance concrete compressive strength using standalone and ensembled machine learning techniques. Materials. 14, 7034 (2021).

Shrestha, D. L. & Solomatine, D. P. Experiments with AdaBoost.RT, an improved boosting scheme for regression. Neural Comput. 18, 1678–1710 (2006).

Sun, Z., Li, Y., Yang, Y., Su, L. & Xie, S. Splitting tensile strength of basalt fiber reinforced coral aggregate concrete: optimized XGBoost models and experimental validation. Constr. Build. Mater. (2024).

Iwashita, T. Energy landscape-driven non-equilibrium evolution of inherent structure in disordered material. Nat. Commun..

Hao, X., Zhang, Z., Xu, Q., Huang, G. & Wang, K. Prediction of f-CaO content in cement clinker: A novel prediction method based on LightGBM and bayesian optimization. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 220, 104461 (2022).

Singh, S. B. Role of water/cement ratio on strength development of cement mortar. J. Building Eng. (2015).

Hashemi, M., Shafigh, P., Karim, M. R. B. & Atis, C. D. The effect of coarse to fine aggregate ratio on the fresh and hardened properties of roller-compacted concrete pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 169, 553–566 (2018).

Poon, C. S. & Lam, C. S. The effect of aggregate-to-cement ratio and types of aggregates on the properties of pre-cast concrete blocks. Cem. Concr. Compos. 30, 283–289 (2008).

Bijen, J. & van Selst, R. Cement equivalence factors for fly ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 23, 1029–1039 (1993).

Amer, I., Kohail, M., El-Feky, M. S., Rashad, A. & Khalaf, M. A. Characterization of alkali-activated hybrid slag/cement concrete. Ain Shams Eng. J. 12, 135–144 (2021).

Mousavi, S. M., Aminian, P., Gandomi, A. H., Alavi, A. H. & Bolandi, H. A new predictive model for compressive strength of HPC using gene expression programming. Adv. Eng. Softw. 45, 105–114 (2012).

Gandomi, A. H., Alavi, A. H., Shadmehri, D. M. & Sahab, M. G. An empirical model for shear capacity of RC deep beams using genetic-simulated annealing. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 13, 354–369 (2013).

Chou, J. S. & Pham, A. D. Enhanced artificial intelligence for ensemble approach to predicting high performance concrete compressive strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 49, 554–563 (2013).

Chou, J. S., Chong, W. K. & Bui, D. K. Nature-inspired metaheuristic regression system: Programming and implementation for civil engineering applications. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 30, 04016007 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 52102392.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yushuai Zhang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft. Wangjun Ren: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - review and editing. Yicun Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review and editing. Yongtao Mi: Conceptualization, Methodology. Jiyong Lei: Conceptualization, Methodology. Licheng Sun: Conceptualization, Methodology.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Ren, W., Chen, Y. et al. Predicting the compressive strength of high-performance concrete using an interpretable machine learning model. Sci Rep 14, 28346 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79502-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79502-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Intelligent low carbon reinforced concrete beam design optimization via deep reinforcement learning

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Comparative analysis of daily global solar radiation prediction using deep learning models inputted with stochastic variables

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Experimental and machine learning prediction of compressive strength of chemically activated RHA based RAC using SHAP and PDP analysis

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Enhanced Compressive Strength and Reduced Thermal Conductivity in Concrete Using a 10% Graphite–Zeolite Sand Replacement

Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering (2025)

-

Few-shot meta-learning for concrete strength prediction: a model-agnostic approach with SHAP analysis

AI in Civil Engineering (2025)