Abstract

Migraine is a common neurological disorder observed after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID 19) infection. However, the intricate relationship between COVID 19 and migraine, particularly the potential mediating role of brain imaging-derived phenotypes (BIPs), remains unclear. This study used linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC), a bidirectional two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) approach, and two-step MR analysis to investigate potential causal links. The robustness of the MR findings was corroborated through generalized summary-data-based Mendelian randomization (GSMR) and MR-Steiger methods. The results of the LDSC analysis revealed that the genetic correlation coefficient between COVID 19 traits and migraine was 0.0277 for infection (P = 0.0051), 0.1690 for hospitalization (P = 0.0016), and 0.1147 for severity (P = 0.0330). The genetic correlation coefficients between COVID 19 infection, hospitalization, severity and migraine and migraine with aura (MA) were 0.2654 (P = 0.0012), 0.2065 (P = 0.0043), and 0.1537 (P = 0.0230), respectively. Two-sample MR analysis revealed a significant causal association of COVID 19 infection (odds ratio [OR] 1.2502, P = 0.0083; OR 1.4956, P = 0.0084), hospitalization (OR 1.0689, P = 0.0138; OR 1.0919, P = 0.0208), and severity (OR 1.0644, P = 0.0072; OR 1.0844, P = 0.0098) with increased risk of migraine and migraine with aura (MA). Cortical thickness (CT), total surface area (TSA), and fractional anisotropy (FA) were identified as BIP intermediaries in the risk trajectory from COVID 19 to migraine. The TSA exhibited a more pronounced mediating effect than did CT. This study revealed that genetically predicted COVID 19 is associated with an increased risk of migraine and MA, and BIPs act as potential mediators of these causal relationships, offering insights into the neurobiological underpinnings of migraine in the context of COVID 19.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent research has broadened our understanding of COVID 19, showing that its impact extends beyond initial respiratory symptoms to include serious neurological effects. Early symptoms of infection often include headaches, which are reported in 10–20% of COVID 19 patients and are associated with a lower risk of death in hospitalized patients1. Moreover, individuals with a history of migraine experience more severe and prolonged headaches, increasing their risk of long-term neurological issues after COVID 19 infection2. Despite the accumulation of epidemiological evidence linking migraine episodes to COVID 19, the underlying causal relationship between these conditions has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

Recent studies have highlighted the impact of COVID 19 on the brain, revealing significant structural and functional changes even in patients with mild infections. Research has shown a decrease in gray matter thickness, increased markers of tissue damage, and a reduction in overall brain volume following SARS-CoV-2 infection3. A genetic link between COVID 19 susceptibility and brain atrophy in certain areas has also been established through a Mendelian randomization (MR) study4. Advancements in MRI technology have shed light on the alterations in brain structure and function associated with migraines, including changes in the insula and basal ganglia, as well as differences in brain activity and structural anomalies in gray and white matter5,6. These observations highlight the urgent need for further research to explore the genetic causes behind these changes and to investigate how COVID 19 may influence migraine development through its impact on brain structure.

MR represents a sophisticated statistical methodology that leverages genetic variations as instrumental variables (IVs) to deduce causal relationships between exposures and outcomes, substantially minimizing the impact of confounding variables7. Linkage disequilibrium score regression (LDSC) is instrumental in identifying potential confounders and estimating heritability in GWAS results. When used to analyze multiple phenotypes, LDSC aids in understanding genetic correlations between traits8. The GSMR complements MR by providing heterogeneity testing in dependent instruments through the heterogeneity-in-dependent instruments (HEIDI) approach, which is crucial for excluding pleiotropic IVs and ensuring accurate causal effect estimations9. The MR-Steiger method further enhances this analysis by confirming the directionality of IVs and identifying potential invalid ones, thus reducing reverse causation risk10. In our study, we first applied LDSC to explore the genetic connections between three COVID 19 traits (infection, hospitalization, severity) and migraine, including its subtypes. We then used a bidirectional two-sample MR approach to assess potential causal links. The integration of the GSMR and MR-Steiger methods augmented the reliability of our findings. Additionally, we explored whether brain structure may act as an intermediary in these associations.

Methods

Data sources

COVID 19-related data were sourced from the COVID 19 Host Genetics Initiative (HGI), which encompasses data from 56 cohorts of European ancestry (available at https://www.covid19hg.org/results/r7/). The migraine GWAS data were sourced from two primary datasets. The first dataset combined multiple studies, including the International Headache Genetics Consortium (IHGC) 2016 (excluding 23andMe), UK Biobank (UKB), GeneRISK, and Helseundersøkelsen i Nord-Trøndelag (HUNT). The second source was the newly released Finngen R9 study. The brain imaging-derived phenotype (BIP) GWAS data encompassed cortical and subcortical brain structures, alongside functional brain measures. The cortical assessment included the evaluation of the occipital lobe volume (OLV), parietal lobe volume (PLV), frontal lobe volume (FLV), temporal lobe volume (TLV), CT, and the TSA. The subcortical analysis included the total subcortical volume (TSV), volumes of the right hippocampus (HC Vol (Right)) and volumes of the left hippocampus (HC Vol (Left)), white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), FA for white matter integrity, and mean diffusivity (MD) for white matter integrity. The fMRI data were derived from the UKB ‘40k’ dataset, released in early 2020, and processed and analyzed by WIN-FMRIB on behalf of the UKB (Supplementary Material Table S1).

Statistical analyses

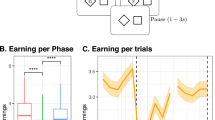

LDSC, a regression-based genetic analysis, was first used to estimate sample overlap and population stratification, assess heritability, and estimate shared genetic effects (LDSC version 1.0.1: https://github.com/bulik/ldsc)11. The intercept in the LDSC regression model represents an estimate of the average contribution of confounding bias to the inflation of the test statistic. A two-sample MR approach was subsequently performed using the TwoSampleMR package of R (version 4.3.0)12. The threshold of independent SNPs strongly associated with exposure as IVs was 5 × 10−6, and the LD clumping was set by an r2 < 0.001 within a 5000 kb window. SNPs associated with confounders and outcomes were manually screened and removed using the PhenoScanner database. The strength of the included SNPs was assessed by R2 and F statistics (Supplementary Material Tables S2–4). Inverse variance weighting (IVW) was used as the main analysis method. MR‒Egger, weighted median, simple mode and weighted mode were used as supplementary analysis methods. Adjustments for multiple testing and the computation of P values corrected for the false discovery rate (FDR) were conducted using the Benjamini‒Hochberg procedure. The mediating effect of BIPs was assessed via two-step MR analysis13. The heterogeneity of the IVs was tested using Cochrane’s Q statistic14. Horizontal pleiotropy was assessed using the MR Egger intercept test, MR-PRESSO global test, MR-PRESSO outlier test, MR-PRESSO distortion test, and leave-one-out analysis. The GSMR approach was further used to explore potential causal relationships, which is used for summary data-based MR analyses by using exposure-related IVs with the highest significance9. The MR Steiger method, implemented in the two-sample MR R package, was used to test the causal direction of each included SNP on the exposure and outcome15. The MR framework design is shown in Fig. 1.

The overall design of the MR analysis in our study. Firstly, the study assessed the causal association between three COVID 19 traits and migraine via using LDSC, which followed by a bidirectional two-sample MR approach. Secondly, BIPs were explored as potential mediators in this association. The mediation effects were quantitatively assessed through three pivotal parameters: β0, β1, and β2. β0 quantifies the total effect of three COVID 19 traits on migraine, encompassing both direct and indirect effects. β1 measures the effect of three COVID 19 traits (exposure) on BIPs (mediator variables), thereby illuminating the mediating role of these traits. β2 evaluated the effect of BIPs (mediator variables) on migraine (outcome), independent of the direct effects of three COVID 19 traits.

Results

LDSC regression analysis

The FinnGen dataset revealed significant genetic associations between the three COVID 19 traits and both migraine and MA (Supplementary Material Table S5). Specifically, the genetic correlation coefficients between the COVID 19 traits and migraine were 0.0277 for infection (P = 0.0051), 0.1690 for hospitalization (P = 0.0016), and 0.1147 for severity (P = 0.0330). The correlation coefficients for MA with COVID 19 infection, hospitalization, and severity were 0.2654 (P = 0.0012), 0.2065 (P = 0.0043), and 0.1537 (P = 0.0230), respectively. However, MO was not significantly associated with any of the COVID 19 traits (P > 0.05). No significant sample overlap was identified (Supplementary Material Table S5).

Causal estimates between COVID 19 and migraine

UVMR analysis was used to analyze the potential causal linkages between COVID 19 and both migraine and MA, and MR-Steiger filtering was used to determine the specific directional influence of each SNP in relation to exposure and outcome (Supplementary Material Table S7). The IVW analysis revealed that each SD increase in COVID 19 infection corresponded to a 0.2502-fold increase in migraine risk (OR 1.2502, 95% CI 1.0592–1.4756, P = 0.0083, PFDR = 0.0249, Power = 93%) and a 0.4956-fold increase in MA risk (OR 1.4956, 95% CI 1.1087–12.0175, P = 0.0084, PFDR = 0.0168, Power = 98%). GSMR analysis confirmed this association (migraine: OR 1.25, PGSMR = 0.0103; MA: OR 1.49, PGSMR = 0.0115). Moreover, each SD increase in genetically predicted COVID 19 hospitalization was associated with a 6.89% increase in migraine risk (OR 1.0689, 95% CI 1.0136–1.1271, P = 0.0138, PFDR = 0.0166, Power = 83%) and a 9.19% increase in MA risk (OR 1.0919, 95% CI 1.0134–1.1764, P = 0.0208, PFDR = 0.2808, Power = 73%) (Table 1, Fig. 2, and Supplementary Material Table S6). These findings from the GSMR analysis were in alignment with the IVW results (migraine: OR 1.06, PGSMR = 0.0143; MA: OR 1.09, PGSMR = 0.0205). Furthermore, MR-Steiger filtering confirmed that the SNPs used in the analysis of the effect of COVID 19 severity on migraine and MA were predominantly associated with COVID 19 severity. IVW analysis further indicated that each SD increase in genetically predicted COVID 19 severity was linked to a 6.44% increased risk of migraine (OR 1.0644, 95% CI 1.0171–1.1139, P = 0.0072, PFDR = 0.0432, Power = 88%) and an 8.44% increased risk of MA (OR 1.0844, 95% CI 1.0197–1.1533, P = 0.0098, PFDR=0.0147, Power = 87%), and these findings were supported by GSMR analysis.

Conversely, reverse MR analysis did not support a causal relationship between migraine or MA and COVID 19 traits (both raw P and PFDR > 0.05) (Table 1, Fig. 2, Supplementary Material Table S6). MR-Steiger filtering did not identify any invalid SNPs that may have biased the MR estimation results.

Causal estimates between COVID 19 and BIPs

The IVW method indicated that each SD increase in COVID 19 infection was associated with a 14.88% decrease in CT (OR 0.8512, 95% CI 0.7649–0.9471, P = 0.0031, PFDR = 0.0217) and an 18.05% reduction in the TSA (IVW: OR 0.8195, 95% CI 0.7339–0.9150, P = 0.0004, PFDR = 0.0056). For genetically predicted COVID 19 hospitalization, each SD increase correlated with a 6.61% decrease in CT (IVW: OR 0.9339, 95% CI 0.8916–0.9783, P = 0.0039, PFDR = 0.0273) and a 9.39% decrease in the TSA (IVW: OR 0.9061, 95% CI 0.8512–0.9646, P = 0.0020, PFDR = 0.0280). Each SD increase in COVID 19 severity corresponded to a 5.58% decrease in CT (IVW: OR 0.9442, 95% CI 0.9195–0.9695, P = 2.14E-05, PFDR = 0.0003) and a 5.49% decrease in the TSA (IVW: OR 0.9451, 95% CI 0.9111–0.9804, P = 0.0026, PFDR = 0.0182). A 23.35% decrease in FA was associated with each SD increase in COVID 19 severity (IVW: OR 0.7665, 95% CI 0.6080–0.9662, P = 0.0244), although this finding did not remain statistically significant after Benjamini‒Hochberg correction (PFDR = 0.1139), suggesting a causal relationship. No significant associations were found between the three COVID 19 traits and other BIPs (Fig. 3).

In the reverse MR analysis with BIPs as exposures, no evidence supported a potential causal association (Fig. 4, Supplementary Material Table S8, 9). The results of the remaining four MR methods are presented in Supplementary Material Table S10.

Causal estimates between migraine and BIPs

In exploring the causal effects of BIPs on migraine and MA, the MR-Steiger filtering method identified no null SNPs. Each SD increase in genetically predicted CT, TSA, and FA reduced migraine risk by 5.09% (IVW: OR 0.9491, 95% CI 0.9117–0.9879, P = 0.0108, PFDR = 0.0378), 14.1% (IVW: OR 0.8590, 95% CI 0.8112–0.9096, P = 1.93E-07, PFDR = 2.71E-06), and 2.87% (IVW: OR 0.9713, 95% CI 0.9501–0.9931, P = 0.0101, PFDR = 0.0471), respectively. For MA, each SD increase in CT and the TSA reduced the risk by 5.2% (IVW: OR 0.9480, 95% CI 0.9103–0.9873, P = 0.0099, PFDR = 0.0462) and 16.44% (IVW: OR 0.8356, 95% CI 0.7723–0.9041, P = 7.93E-06, PFDR = 0.0001), respectively, whereas one SD increase in WMH lowered the risk by 24.69% (OR 0.7531, 95% CI 0.6447–0.8799, P = 0.0004, PFDR = 0.0021) (Fig. 5, Supplementary Material Table S11).

Moreover, the IVW revealed that a one-SD increase in left HC Vol and fMRI was associated with an increased risk of migraine by 0.2% (OR 1.0002, 95% CI 1.0000–1.0004, P = 0.0343, PFDR = 0.0800) and 21.71% (OR 0.7829, 95% CI 0.6509–0.9418, P = 0.0094, PFDR = 0.0658), respectively. Conversely, per SD increases in FLV, fMRI, and FA were linked to reduced risks of MA (FLV: OR 0.9839, 95% CI 0.9695–0.9986, P = 0.0314, PFDR = 0.0733; fMRI: OR 0.7713, 95% CI 0.5981–0.9948, P = 0.0455, PFDR = 0.0910; FA: OR 0.9586, 95% CI 0.9232–0.9955, P = 0.0282, PFDR = 0.0790). However, after Benjamini‒Hochberg correction, PFDR values exceeding 0.05 suggested that these associations may be suggestive rather than definitive (Fig. 5, Supplementary Material Table S11). The results of the other four MR methods are presented in Supplementary Material Table S12.

In the reverse MR analysis with BIPs as outcomes, no genetic association for the casual effect of migraine or MA on BIPs was identified after excluding the invalid SNPs linked to BIPs via MR-Steiger (raw P and PFDR > 0.05) (Supplementary Material Table S13).

Mediation analysis

In a two-step MR framework involving 13 BIPs, three potential mediating BIPs were identified. Specifically, CT and the TSA were found to mediate the effects of COVID 19 infection and hospitalization on migraine and MA (Table 2). For the impact of COVID 19 infection on migraine, the mediating effect proportions for CT and the TSA were 3.70% and 13.55%, respectively. In the case of the impact of hospitalization for COVID 19 on migraine, these proportions were 5.36% for CT and 22.48% for the TSA. For the effect of COVID 19 infection on MA, CT and the TSA mediated 2.14% and 8.89% of the effect, respectively. For the impact of COVID 19 hospitalization on MA, the proportions were 4.15% for CT and 20.15% for the TSA. Additionally, CT and the TSA mediated 3.78% and 12.50%, respectively, of the impact of COVID 19 severity on MA. For the association of COVID 19 severity with migraine, CT and the TSA mediated 4.81% and 13.74% of the effect, respectively, and FA contributed 2.12% to the mediation effect.

Sensitivity analysis

In our investigation of the bidirectional associations between COVID 19 and both migraine and MA, no heterogeneity was observed, as indicated by the Cochran’s Q statistic (P > 0.05) (Supplementary Material Table S14). Furthermore, neither the MR‒Egger intercept nor the MR-PRESSO global test indicated the presence of horizontal pleiotropy (P > 0.05). When the associations between COVID 19 incidence and BIPs were analyzed, Cochran’s Q test revealed no heterogeneity. Similarly, the MR‒Egger intercept and the MR-PRESSO global test revealed no evidence of horizontal pleiotropy. Conversely, when the influence of BIPs on the three COVID 19 traits was assessed, significant heterogeneity was detected in the influence of CTs on COVID 19 infection (Cochrane’s Q test P = 0.0192; MR-PRESSO global test P = 0.020) and hospitalization (Cochrane’s Q test P = 9.42E-07; MR-PRESSO global test P = 0.001). Similar heterogeneity and pleiotropy were observed for the effect of the TSA on COVID 19 severity (Cochrane’s Q test P = 0.0202; MR-PRESSO global test P = 0.023) (Supplementary Material Table S15). Importantly, no heterogeneity or pleiotropy was detected between BIPs and either migraine or MA (Supplementary Material Table S16). Moreover, the leave-one-out sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of our results, as the exclusion of any single SNP did not significantly alter the findings. The funnel plot, scatter plot, and forest plot analyses also revealed no evident outliers. The detailed visual representations of these analyses are provided in Supplementary Materials Figures S1-142.

Discussion

This study leveraged extensive GWAS datasets for the first time to thoroughly investigate the causal link between COVID 19 and migraine. Our analysis revealed a causal effect of COVID 19 traits (infection, hospitalization, severity) on the increased risk of migraine and MA, and the mediation analysis suggested that both CT and the TSA play intermediary roles in the risk effect of COVID 19 on migraine.

Approximately 50% of COVID 19 patients report headaches, with a high prevalence among younger individuals and those with a history of primary headaches or migraine2. Early-phase COVID 19 headaches typically present as bilateral, ranging from moderate to severe intensity, and predominantly manifest as migraine or tension-type headache16. In alignment with previous research, our study indicates increased risks of migraine and MA in individuals who are genetically predisposed to suffer from or be hospitalized for COVID 19. Nonmigraineurs with COVID 19 often develop primary headaches, whereas those with preexisting migraine may experience exacerbated symptoms2. However, our study revealed no evidence of increased COVID 19 risk due to migraine, which aligns with recent studies17.

Neuropathological and proteomic analyses of postmortem brain tissues from COVID 19 patients have revealed the presence of SARS-CoV-2 and alterations in carbon metabolism, suggesting potential structural changes in the brain18,19. Some retrospective studies have revealed diverse imaging anomalies related to COVID 19 in brain anatomy, such as signal abnormalities in the medial temporal lobe, cerebral enhancement, and alterations in white matter signals, alongside thalamic hyperactivation20,21,22,23. Consistent with the findings of a recent MR study4, our results support that COVID 19 is negatively correlated with the TSA and CA. However, in contrast to the MR findings that certain BIPs, such as CT in the left inferior temporal area and the TSA, are positively correlated with COVID 19 infection and hospitalization24, our study revealed a negative correlation between the TSA and COVID 19 hospitalization. These findings suggest that individual brain anatomy variations may influence susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Specifically, a larger meningeal surface area, associated with enhanced meningeal immunity, could mitigate the severity of COVID 19 symptoms and hospitalization risk. Individuals with a reduced brain surface area, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients, may exhibit more severe symptoms after COVID 19 infection, necessitating hospitalization.

In exploring the genetic association between BIPs and migraine, our analysis identified several BIPs with potential causal effects on migraine and MA. A recent MR study suggested a potential causal relationship between reduced total brain, hippocampal and ventral diencephalon volume and increased migraine risk, and reduced amygdala and diencephalon volume correlated with increased migraine risk25. Other studies have shown a reduction in CT within the visual cortex during the migraine interictal period26. This reduction may be due to heightened excitability in the visual cortex, predisposing it to spontaneous neuronal depolarization and leading to cortical spreading depression (CSD)27. However, we observed a contributory effect of the FLV, OLV, PLV, and TLV. This effect could be due to the inhibitory influence of the frontal cortex on pain pathways. For example, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) of the prefrontal cortex has demonstrated efficacy in chronic migraine therapy. Furthermore, cerebral metabolic factors also play a role in migraine pathogenesis28. Brain areas experiencing energy deficiency may exhibit hyperactivation and sensitization of the trigeminal vascular system, precipitating migraine attacks. Additionally, altered connectivity has been identified, with enhanced connectivity predominantly observed in regions related to migraine pathophysiology (e.g., the thalamus, hypothalamus, precentral gyrus (PCG), superior frontal gyrus (SFG), and hippocampus), suggesting potential plastic adaptations to repetitive pain stimuli29. Our MR analysis also revealed an association between migraine attacks and hippocampal volume. Widespread neuronal hyperexcitability may be driven by thalamocortical dysrhythmia30, impaired modulatory brainstem circuits regulating excitability31, and dysregulated cortical, thalamic32, and brainstem33 functions caused by limbic structures, such as the hypothalamus, amygdala, nucleus accumbens, caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus. The disruption of thalamocortical–thalamic connections, which are essential for multisensory integration, could be a key contributor to the clinical manifestation of migraine symptoms34. These structures, which are involved in nociceptive modulation and perception, could serve as potential biomarkers for predicting the response to migraine treatments. Our study underscores the role of these brain regions in migraine attacks.

This study did not reveal any genetic associations of migraine or MA with BIPs. In contrast, previous MR studies have revealed a significant negative genome-wide correlation between migraine risk and intracranial volume but not between migraine risk and subcortical regions25. Anatomically, migraine sufferers often demonstrate cortical and subcortical alterations, including cortical thickening in the somatosensory cortex35, increased gray matter density in the caudate, and gray matter volume loss in multiple regions, including the superior temporal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, precentral gyrus, anterior cingulate cortex, amygdala, parietal operculum, middle and inferior frontal gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, and bilateral insula35. It remains unclear whether alterations in BIPs observed in migraine patients are the result of genetic factors or chronic exposure to pain and stress. Moreover, rapid changes in CT and volume may occur under different conditions or after exposure to specific stimuli. Consequently, structural changes in BIPs during migraine attacks or interictal periods can yield variable results. This highlights the complexity of interpreting structural brain changes in migraine and underscores the need for further research to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

By applying mediation analysis, this study revealed that CT and the TSA are key mediators in the causal association between genetic variants that increase the risk of COVID 19 infection/hospitalization and migraine. This finding has implications for COVID 19 patients, and underscores the importance of examining cortical structures (especially gray matter) in these patients to analyze cortical function, which includes assessing potential impairments in execution, learning, and memory. Such assessments are vital for elucidating the emergence of neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID 19 infection36. Intriguingly, our findings indicated a more pronounced mediation effect of the TSA than of CT. This aligns with the prevailing hypothesis that COVID 19 exacerbates damage to the blood‒brain barrier and meninges, subsequently manifesting as impaired brain structures. In this context, the extent of area damage is posited to be more consequential than variations in CT. Moreover, existing studies have indicated that cortical surface area is more heritable than CT is37. For example, Wu et al. reported a causal relationship between AD vulnerability and a decreased surface area of the precentral and isthmus cingulate38, whereas research by Hoogman, Schmaal et al. revealed that children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD) presented lower TSA39. Furthermore, Sun et al. reported that individuals with subjective cognitive decline (SCD) presented with decreased cortical surface area40. Collectively, these studies indicate a consistent reduction in cortical surface area across various neuropsychiatric disorders, suggesting that alterations in the cortical surface area may more accurately reflect changes in cortical structure. FA also contributes to the severity of migraine caused by COVID 19, albeit with a modest intermediary effect of 2.12%. As previously noted, DIC and severe inflammatory responses are frequently observed in patients with severe COVID 19, who are more prone to ischemic cerebral-vascular events. These ischemic changes are known to be accompanied by lower FA values41. However, current studies exploring the relationship between FA and migraine suggest a positive correlation42, indicating that further research is essential to unravel the complicated intricate relationships.

Our study also has limitations. First, considering the variability in the accessibility and accuracy of COVID 19 testing, as well as discrepancies in the reporting of asymptomatic infections, it is possible that many COVID 19 cases remain unreported. Additionally, prevalent data on migraine are derived mainly from hospitalized populations, often omitting severely affected patients because of challenges in documenting headache characteristics. This limitation is compounded by potential disparities arising from the varied expertise of health care professionals (neurologists versus nonneurologists). Second, the analysis does not fully account for variables influencing COVID 19 hospitalization and severity, such as different medical conditions across countries, specifics regarding peripheral oxygen saturation (Spo2) levels, and hospital procedures. Inherent recruitment bias also cannot be discounted. Third, the study does not sufficiently address how factors such as vaccination against COVID 19, vaccine type, and vaccination timing may affect the results. The challenge in distinguishing positive test results due to infection versus vaccination and the lack of analysis of the impact of other COVID 19 variants, such as Delta or Omicron43, further complicate the findings. Fourth, the study failed to explore the interplay between COVID 19 and migraine within specific demographic subgroups, notably age and sex, which are known correlates of migraine incidence. The correlation between migraine risk and brain morphometrics exhibits sex differences. For example, disease-related structural changes in the insula and precuneus regions are specific to female migraineurs, disease-related structural changes in the parahippocampal gyrus are specific to male migraineurs, and functional changes in response to noxious heat show more pronounced responses in female migraineurs in regions such as the amygdala and parahippocampus. Fifth, the potential for nasopharyngeal swabbing to induce migraine attacks44, coupled with the variable sensitivity and specificity of the PCR test, introduces diagnostic bias. The absence of specific SARS-CoV-2 strains identified in participants further compounds this bias. Sixth, isolation measures, the type of protective equipment, and the quarantine environment may influence migraine attacks45, thereby introducing confounding variables. Seventh, the GWAS statistics used in this study were predominantly from individuals of European ancestry. While this may reduce racial variances, caution is warranted when these findings are generalized to diverse racial backgrounds. Eighth, factors such as COVID 19-induced hypoxemia, fever, sleep disturbances, and dehydration may trigger or exacerbate migraine, warranting further investigation. Ninth, there are differences in the LD structure between the Finnish and UK/European populations, with heterogeneity potentially influenced by factors such as population history (e.g., migration, admixture, and selection), selective pressures (changes in allele frequencies within specific populations), genetic drift (random changes in allele frequencies in small populations), and environmental factors (geographic and environmental conditions exerting selective pressures on genes). While we acknowledge the consistency issues of LDSC across different datasets, we believe this does not diminish the value of our findings. Finally, the potential biological functions of SNPs may extend beyond current comprehension, particularly in relation to their interaction with environmental factors and lifestyle; for example, specific odors and taste sensations—attributable to substances such as smoke, fermented foods, and chocolate—have been identified as migraine triggers. This complexity underscores the challenge in determining whether the pleiotropic effect is completely eliminated.

Conclusion

This study implemented a comprehensive MR analysis and revealed that genetically predicted COVID 19 infection, hospitalization and severity were causally associated with an increased risk of migraine and MA and were partially mediated by certain BIPs. Elucidating these underlying pathways could shed light on the neurobiological underpinnings of migraine in the context of COVID 19.

Data availability

The COVID 19 GWAS dataset is publicly available from the COVID 19-HGI GWAS meta-analyses (round 7), https://www.covid19hg.org/results/r7/. The migraine and subtype datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available in the FinnGen repository, https://www.finngen.fi/ or from the corresponding author on reasonable request.An additional dataset for migraine GWAS is sourced from the IHGC. The summary statistics for migraine GWAS can be accessed by directly contacting the authors of the respective studies. Further details are available at the IHGC website: https://www.headachegenetics.org/. The BIPs GWAS dataset is publicly accessible through the GWAS Catalog database, available at https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/. Specific GWAS-IDs for accessing the data are as follows: OLV: GCST008703, PLV: GCST008704, TLV: GCST008705, FLV: GCST008715, CT: GCST010700, TSA: GCST010701, HC Vol (Right): GCST90085872, HC Vol (Left): GCST90085831, FA (WMI): GCST010102, MD (WMI): GCST010103, WMH: GCST90003862, TSV: GCST90105077, fMRI: GCST90004558. Corresponding author Hongbei Xu will provide the data upon reasonable request.

References

Mao, L. et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan China. JAMA Neurol. 77, 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 (2020).

Membrilla, J. A., de Lorenzo, Í., Sastre, M. & Díaz de Terán, J. Headache as a cardinal symptom of coronavirus disease 2019: A cross-sectional study. Headache 60, 2176–2191 (2020).

Douaud, G. et al. SARS-CoV-2 is associated with changes in brain structure in UK Biobank. Nature 604, 697–707. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04569-5 (2022).

Zhou, S. et al. Causal effects of COVID-19 on structural changes in specific brain regions: A Mendelian randomization study. BMC Med. 21, 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02952-1 (2023).

Maleki, N. et al. Migraine attacks the Basal Ganglia. Mol. Pain 7, 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8069-7-71 (2011).

Jia, Z. & Yu, S. Grey matter alterations in migraine: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage Clin. 14, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2017.01.019 (2017).

Davies, N. M., Holmes, M. V. & Davey Smith, G. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: A guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. Bmj 362, k601. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k601 (2018).

Bulik-Sullivan, B. et al. An atlas of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat. Genet. 47, 1236–1241. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3406 (2015).

Zhu, Z. et al. Causal associations between risk factors and common diseases inferred from GWAS summary data. Nat. Commun. 9, 224. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02317-2 (2018).

Hemani, G., Tilling, K. & Davey Smith, G. Orienting the causal relationship between imprecisely measured traits using GWAS summary data. PLoS Genet. 13, e1007081. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1007081 (2017).

Duncan, L. E. et al. Genetic correlation profile of schizophrenia mirrors epidemiological results and suggests link between polygenic and rare variant (22q11.2) cases of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 44(6), 1350–1361. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbx174 (2018).

Yang, G. & Schooling, C. M. Genetically mimicked effects of ASGR1 inhibitors on all-cause mortality and health outcomes: A drug-target Mendelian randomization study and a phenome-wide association study. BMC Med. 21, 235. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02903-w (2023).

Zhao, S. S., Holmes, M. V., Zheng, J., Sanderson, E. & Carter, A. R. The impact of education inequality on rheumatoid arthritis risk is mediated by smoking and body mass index: Mendelian randomization study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 61, 2167–2175. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keab654 (2022).

Cohen, J. F. et al. Cochran’s Q test was useful to assess heterogeneity in likelihood ratios in studies of diagnostic accuracy. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 68, 299–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.09.005 (2015).

Lutz, S. M. et al. The influence of unmeasured confounding on the MR Steiger approach. Genet. Epidemiol. 46, 139–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/gepi.22442 (2022).

Rocha-Filho, P. A. S., Albuquerque, P. M., Carvalho, L. C. L. S., Gama, M. D. P. & Magalhães, J. E. Headache, anosmia, ageusia and other neurological symptoms in COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. J. Headache Pain https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01367-8 (2022).

Rist, P. M., Buring, J. E., Manson, J. E., Sesso, H. D. & Kurth, T. History of migraine and risk of COVID-19: A cohort study. Am. J. Med. 136, 1094–1098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.07.021 (2023).

Rogers, J. P. et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7, 611–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(20)30203-0 (2020).

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271-280.e278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 (2020).

Kremer, S. et al. Brain MRI findings in severe COVID-19: A retrospective observational study. Radiology 297, E242-e251. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020202222 (2020).

Kremer, S. et al. Neurologic and neuroimaging findings in patients with COVID-19: A retrospective multicenter study. Neurology 95, e1868–e1882. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000010112 (2020).

Yoon, B. C. et al. Clinical and neuroimaging correlation in patients with COVID-19. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 41, 1791–1796. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6717 (2020).

Chammas, A. et al. Collicular Hyperactivation in Patients with COVID-19: A New Finding on Brain MRI and PET/CT. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 42, 1410–1414. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A7158 (2021).

Fan, Z. et al. Causal association of the brain structure with the susceptibility, hospitalization, and severity of COVID-19: A large-scale genetic correlation study. J. Med. Virol. 95, e28651. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.28651 (2023).

Mitchell, B. L. et al. Elucidating the relationship between migraine risk and brain structure using genetic data. Brain 145, 3214–3224. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awac105 (2022).

Lorenz, J., Minoshima, S. & Casey, K. L. Keeping pain out of mind: The role of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in pain modulation. Brain 126, 1079–1091. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awg102 (2003).

Mathew, A. A. & Panonnummal, R. Cortical spreading depression: Culprits and mechanisms. Exp. Brain Res. 240, 733–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-022-06307-9 (2022).

Neubauer, J. A. & Sunderram, J. Oxygen-sensing neurons in the central nervous system. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985(96), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00831.2003 (2004).

Gomez-Pilar, J. et al. Headache-related circuits and high frequencies evaluated by EEG, MRI, PET as potential biomarkers to differentiate chronic and episodic migraine: Evidence from a systematic review. J. Headache Pain 23, 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01465-1 (2022).

Steriade, M., McCormick, D. A. & Sejnowski, T. J. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science 262, 679–685. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8235588 (1993).

Bahra, A., Matharu, M. S., Buchel, C., Frackowiak, R. S. & Goadsby, P. J. Brainstem activation specific to migraine headache. Lancet 357, 1016–1017. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04250-1 (2001).

Burstein, R. et al. Thalamic sensitization transforms localized pain into widespread allodynia. Ann. Neurol. 68, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21994 (2010).

Moulton, E. A. et al. Interictal dysfunction of a brainstem descending modulatory center in migraine patients. PLoS ONE 3, e3799. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003799 (2008).

Bolay, H. Thalamocortical network interruption: A fresh view for migraine symptoms. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 50, 1651–1654. https://doi.org/10.3906/sag-2005-21 (2020).

DaSilva, A. F., Granziera, C., Snyder, J. & Hadjikhani, N. Thickening in the somatosensory cortex of patients with migraine. Neurology 69, 1990–1995. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000291618.32247.2d (2007).

Lu, Y. et al. Cerebral micro-structural changes in COVID-19 patients - An MRI-based 3-month follow-up study. EClinicalMedicine 25, 100484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100484 (2020).

Eyler, L. T. et al. A comparison of heritability maps of cortical surface area and thickness and the influence of adjustment for whole brain measures: A magnetic resonance imaging twin study. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 15, 304–314. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2012.3 (2012).

Wu, B. S. et al. Cortical structure and the risk for Alzheimer’s disease: A bidirectional Mendelian randomization study. Transl. Psychiatry 11, 476. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01599-x (2021).

Hoogman, M. et al. Brain imaging of the cortex in ADHD: A coordinated analysis of large-scale clinical and population-based samples. Am. J. Psychiatry 176, 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18091033 (2019).

Sun, Y. et al. Anxiety correlates with cortical surface area in subjective cognitive decline: APOE ε4 carriers versus APOE ε4 non-carriers. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 11, 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-019-0505-0 (2019).

Das, A. et al. Acute microstructural changes after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction assessed with diffusion tensor imaging. Radiology 299, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2021203208 (2021).

Planchuelo-Gómez, Á. et al. White matter changes in chronic and episodic migraine: A diffusion tensor imaging study. J. Headache Pain 21, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-1071-3 (2020).

van der Arend, B. W. H., Bloemhof, M. M., van der Schoor, A. G., van Zwet, E. W. & Terwindt, G. M. Effect of COVID vaccination on monthly migraine days: A longitudinal cohort study. Cephalalgia 43, 3331024231198792. https://doi.org/10.1177/03331024231198792 (2023).

Madera, J., Rodríguez-Rodriguez, E. M., González-Quintanilla, V., Pérez-Pereda, S. & Pascual, J. Peripheral stimulation of the trigeminal nerve by nasopharyngeal swabbing as a possible trigger of migraine attacks. Rev. Neurol. 76, 227–233. https://doi.org/10.33588/rn.7607.2022271 (2023).

Verhagen, I. E., van Casteren, D. S., de Vries Lentsch, S. & Terwindt, G. M. Effect of lockdown during COVID-19 on migraine: A longitudinal cohort study. Cephalalgia 41(7), 865–870. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102420981739 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The study team extends heartfelt gratitude to all participants and their families, as well as the dedicated clinical staff at each involved hospital, for their invaluable support and contributions to this project. Here, we especially appreciated Kun Yu for her help in drafting and analyzing the data in this study.

Funding

The funding statement were provided by National Natural Science regional foundation project (Grant No. 82160242), Basic research project of Guizhou science and technology plan (Grant No. qiankehe foundation ZK [2021] General 413), Doctoral research start-up fund (Grant No. gyfybsky-2021-23).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: W.C., Y.X.J., and Y.F.O. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: H.B.X. Statistical analysis: W.C., P.Y., and H.Q.C. Obtained funding: H.B.X. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, H., Chen, W., Ju, Y. et al. Brain structures as potential mediators of the causal effect of COVID 19 on migraine risk. Sci Rep 14, 27895 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79530-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79530-9