Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are the most common bacteria co-isolated from chronic infected wounds. Their interactions remain unclear but this coexistence is beneficial for both bacteria and may lead to resistance to antimicrobial treatments. Besides, developing an in vitro model where this coexistence is recreated remains challenging, making difficult their study. The aim of this work was to develop a reliable polymicrobial in vitro model of both species to further understand their interrelationships and the effects of different antimicrobials in coculture. In this work, bioluminescent and fluorescent bacteria were used to evaluate the activity of two antiseptics (chlorhexidine and thymol) against these bacteria planktonically grown, or when forming single and mixed biofilms. At the doses tested (0.4-1,000 mg/L), thymol showed selective antimicrobial action against S. aureus in planktonic and biofilm states, in contrast with chlorhexidine which exerted antimicrobial effects against both bacteria. Furthermore, the initial conditions for both bacteria in the co-culture determined the antimicrobial outcome, showing that P. aeruginosa impaired the proliferation and metabolism of S. aureus. Moreover, S. aureus showed an increased tolerance against antiseptic treatments when co-cultured, attributed to the formation of a thicker mixed biofilm compared to those obtained when monocultured, and also, by the reduction of S. aureus metabolic activity induced by diffusible molecules produced by P. aeruginosa. This work underlines the relevance of polymicrobial populations and their crosstalk and microenvironment in the search of disruptive and effective treatments for polymicrobial biofilms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The importance of pathogenic polymicrobial infections is becoming increasingly recognized, particularly in the context of biofilm formation, where various bacterial species interact synergistically or antagonistically competing for resources. In this context, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are two commonly co-isolated bacteria in pulmonary infections and on chronic topical wounds1. The interactions between these two bacteria in co-infected tissues have been the focus of continuous research, as their coexistence contributes to enhanced virulence. It has been reported that wounds infected with both species typically exhibit delayed closure compared to wounds infected with a single species2. Alongside factors related to the immune response by the host, this delayed wound closure can be attributed to the increased expression of S. aureus virulence factors during co-infection, a pattern reported for the methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) strain USA3002.

There is no consensus on whether these bacteria have an antagonistic or mutualist relationship in complex physiological media. Some studies indicate that early colonisation by P. aeruginosa shows strong antagonism towards S. aureus3, through the secretion of a wide variety of anti-staphylococcal molecules and proteases that inhibit S. aureus growth and proliferation4,5. This process induces a metabolic transition of S. aureus from aerobic respiration to fermentation and eventually leads to a reduction in S. aureus viability. In response to this hostile environment, S. aureus may adapt to P. aeruginosa virulence factors by increasing biofilm formation and by the presence of small colony variants inside infected eukaryotic cells4. In return, this would provide S. aureus with a greater capacity to withstand antimicrobial therapies. Additionally, exoproducts from P. aeruginosa have been shown to promote the production of staphyloxanthin, further enhancing the virulence of S. aureus67. Other studies have shown that S. aureus supports colonisation and pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa by inhibiting its phagocytosis by eukaryotic cells8. It has been proposed that, during the course of chronic infection, P. aeruginosa may find evolutionarily favourable to maintain a population of S. aureus to help counteract the host’s immune response. Recent studies show that P. aeruginosa populations thrive in the presence of toxin-producing S. aureus strains in both lung and wound infections2,9. Moreover, mutant strains of Pseudomonas that have reduced anti-staphylococcal capacity are commonly isolated in chronic infections of patients with cystic fibrosis10.

In multicellular communities, collective microbial dynamics generate a complex ecosystem characterised by both microbe-microbe and microbe-environment interactions. These features must somehow be present in in vitro models, but they are barely reproducible in planktonic cultures. Co-cultures of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa have been performed using modified media in static in vitro conditions, anoxia, microtiter plates, Calgary biofilm devices or even directly on mammalian cells11,12,13. Nevertheless, the development of an experimental model to recreate this coexistence proves to be a challenging task, as the in vitro interaction between both species appears to be antagonistic at first. Interestingly, while P. aeruginosa strongly inhibited in vitro the growth of S. aureus, this effect was considerably less pronounced in vivo2. This matter adds complexity to the assessment of the effectiveness of antimicrobial treatments against these polymicrobial communities.

A deeper understanding of the behaviour of co-cultures of these opportunistic bacteria is of extreme importance, not only because of their mutual impact on the bacterial behaviour and metabolic activity, but also because some studies have shown that their interplay contributes to antimicrobial tolerance. Notably, it has been reported that when S. aureus is able to coexist with P. aeruginosa in a co-culture, its tolerance to antibiotics significantly increases11,14. Conversely, there have also been studies indicating that P. aeruginosa can reduce the susceptibility of S. aureus to antibiotic treatment through mechanisms such as rhamnolipid production, HQNO, and LasA15,16.

In this study, a reliable in vitro model of a polymicrobial biofilm of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was successfully established to understand the interrelationships and crosstalk between both species and the effects of different antimicrobials under these conditions. The use of bioluminescent and fluorescent strains of both species was proposed to study optically the growth kinetics and metabolic state of these bacteria over time. It was investigated how the initial conditions of both bacterial species influenced their final interaction within the co-culture. Then, the antimicrobial activity of thymol (THY) and chlorhexidine (CHXD) was compared against both species in their planktonic state, as well as when forming single and polymicrobial biofilms. This comparison aimed to determine whether bacteria growth may change in polymicrobial biofilms and to help in the identification of improved antimicrobial treatments using an in vitro model that mimics the polymicrobial nature of human-relevant biofilms.

Results and discussion

Establishment of S. aureus - P. aeruginosa mixed biofilm

Two different strategies were assessed for developing an in vitro model of a polymicrobial biofilm containing both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa (Fig. 1). Using bioluminescent strains together with wild-type strains, the bioluminescence of both species was monitored over a 48 h period in parallel experiments. In both cases, the P. aeruginosa strains were added at progressively increased concentrations whereas S. aureus strains were always added at 107 colony forming units (CFU)/mL.

In the first approach, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa were mixed as planktonic co-cultures. The normalised kinetics of the bioluminescent strains, as well as the bacterial count in the culture at the end of the experiments, are represented in Fig. 1.

Bioluminescence signals from (a) Planktonic S. aureus Xen36 (107 CFU/mL) co-cultured with increasing amounts of planktonic P. aeruginosa PAO1 (101-108 CFU/mL) and (b) Planktonic P. aeruginosa Lux (101-108 CFU/mL) co-cultured with a fixed amount of S. aureus ATCC 29213 (107 CFU/mL). The acronym NSI stands for “Normalized Signal Intensity”. Control samples (Ctrl) represent the normal growth of cultures of S. aureus without the addition of P. aeruginosa. (c) Bacterial counts of both species in the cultures after 48 h (data obtained with conditions (a) and (b) were similar). The data are represented as Mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Bioluminescence kinetics of S. aureus Xen36 exhibited a concentration-dependent suppression when co-cultured with P. aeruginosa PAO1, being ultimately reduced to levels close to the background signal (Fig. 1a). This observation suggested a substantial influence of P. aeruginosa PAO1 presence on S. aureus Xen36 bioluminescence which is directly related to its metabolic activity. Conversely, the bioluminescence signal of P. aeruginosa Lux remained unaltered under the presence of non-bioluminescent planktonic S. aureus 29213, depending solely on its initial concentration (Fig. 1b).

The analysis of the bacterial counts in the culture at the end of the experiment (Fig. 1c) aimed to assess whether the decrease in bioluminescence resulted from a reduction in bacterial numbers, from a decline in the metabolic activity, or from a combination of both factors. For P. aeruginosa concentrations ranging from 102 to 104 CFU/mL, S. aureus growth was slightly inhibited, as its concentration was arrested around 2 logs (107 CFU/mL) compared to that of the control sample. For P. aeruginosa concentrations between 105 and 108 CFU/mL, S. aureus concentration was significantly reduced, resulting in a decrease of 106 CFU/mL compared to that of the control sample. Because no substrate limitation was present, S. aureus growth inhibition may be attributed to the presence of anti-staphylococcal compounds released by P. aeruginosa. In this sense, previous studies have also revealed the prevalence of P. aeruginosa in planktonic cultures even using different culture media11 or clinical strains3.

In the second approach, the different strains of S. aureus were first allowed to grow into a 48-hour-old mature biofilm. Subsequently, a co-culture was established by adding increasing concentrations of planktonic P. aeruginosa. Figure 2 displays both the bioluminescence of the strains and the final bacterial counts. Unlike the first approach, where the relative bioluminescence measured at 48 h decreased with increasing P. aeruginosa concentrations, a constant low level of relative bioluminescence (a 2.5 log reduction compared to pure S. aureus biofilm) was observed regardless of the initial P. aeruginosa concentration (Fig. 2a and b). Nevertheless, when S. aureus Xen36 was already forming a mature biofilm, the presence of planktonic P. aeruginosa did not significantly inhibit its growth after 48 h (Fig. 2c). Despite a one-log reduction compared to the control, both species coexisted in the culture, indicating that S. aureus biofilm may provide some level of protection from the bactericidal and inhibitory effects caused by P. aeruginosa compared to the results observed in their planktonic state. It has been widely reported that when P. aeruginosa and S. aureus are grown together in co-culture, P. aeruginosa becomes dominant, outcompeting, and outgrowing S. aureus16. Herein, we demonstrate that under co-culture conditions the growth of one species depends on the concentration of the other and on its status (sessile or planktonic). These findings are consistent with previous studies that have shown that when S. aureus serves as the pioneer colonizer in biofilm growth assays, it promotes the attachment of P. aeruginosa17. Additionally, these studies suggest that individuals pre-colonized with S. aureus are more vulnerable to secondary colonization by P. aeruginosa.

Bioluminescence signals from (a) 48-hours old S. aureus Xen36 biofilm supplemented with increasing amounts of planktonic P. aeruginosa PAO1 (101-108 CFU/mL) or (b) 48-hours old S. aureus ATCC 29,213 supplemented with increasing amounts of planktonic bioluminescent P. aeruginosa lux (101-108 CFU/mL). (c) Mean bacterial counts of both species in the cultures after 48 h (data obtained with conditions (a) and (b) were similar). The data are represented as Mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Study of the interaction between S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in mixed biofilm

To explore if P. aeruginosa requires direct contact with S. aureus to hinder its growth, an experiment using Transwell® inserts was conducted, in which the bacterial species shared liquid media while avoiding physical contact. Figure 3a showcases an overview of this experiment, in addition to the measurement of the bioluminescent kinetics and bacteria counts after 48 h.

Interaction between both species in mixed biofilm: (a) Schematic overview of the methodology developed to evaluate the interaction between bacterial species: i.S. aureus Xen36 single biofilm culture without insert. ii.S. aureus Xen36 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 mixed biofilm without insert. iii.S. aureus Xen36 and P. aeruginosa single biofilm in the insert. iv.S. aureus Xen36 single biofilm, and S. aureus Xen36 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 mixed biofilm in the insert. (b) Bioluminescence signal of S. aureus Xen36 over 48 h. (c)S. aureus Xen36 counting measured after 48 h.

As observed in Fig. 3b, the bioluminescence signal of S. aureus Xen36 was only reduced after 24 h when it was in direct physical contact with P. aeruginosa. In cases where P. aeruginosa was grown in the insert, the signal remained at levels similar to those of the control culture. However, by the 48-hour mark, the signal in all cultures, except for the control, decreased to baseline levels. As depicted in Fig. 3c, the interaction with P. aeruginosa resulted in a slight reduction of approximately one logarithm in the growth of S. aureus, although this value is not statistically significant. These experiments suggest that the decrease in bioluminescence may be attributed to a suppression of their metabolic activity. It is also worth mentioning that the physical proximity of P. aeruginosa could potentially accelerate this process.

To determine whether P. aeruginosa requires the presence of S. aureus to secrete molecules that interfere with S. aureus metabolism, conditioned medium (CM), in which P. aeruginosa was grown alone, was added to a 48-hours-old S. aureus GFP biofilm. For these experiments, the bioluminescent strain (S. aureus Xen36) was substituted with the fluorescent strain (S. aureus GFP) considering its suitability for subsequent confocal microscopy studies. Unlike bioluminescence, which depends on both ATP and protein synthesis, fluorescence is solely reliant on GFP production, offering more specific insights into how P. aeruginosa-secreted molecules impact S. aureus. The GFP fluorescence was then monitored over a 70-hour period (Fig. 4).

When S. aureus GFP was not exposed to CM, GFP fluorescence intensity showed a steady increase over time, reaching a plateau after 18 h. Conversely, when S. aureus was exposed to CM, a rapid and substantial decrease in GFP fluorescence intensity was observed within the first hour, followed by an overall reduction in the maximum fluorescence intensity reached. This suppression effect on GFP fluorescence was found to be concentration-dependent, with a degree of suppression gradually decreased as the CM was diluted. These results suggest that P. aeruginosa PAO1 produced one or more diffusible molecules capable of suppressing both the luminescence and fluorescence of S. aureus biofilms in a concentration-dependent manner, without affecting bacterial viability, as evidenced by stable CFU/mL counts. The decrease in bioluminescence at a constant bacterial count may result from reduced ATP levels, oxygen availability, or protein synthesis. Meanwhile, the reduction in fluorescence likely points to the suppression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) synthesis. However, the potential impact on ATP levels or protein synthesis was not assessed in this study and should be evaluated to validate this hypothesis.

The anti-staphylococcal properties of P. aeruginosa were initially documented in the 1950s18. During this period, researchers identified 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline N-oxide (HQNO) as the primary compound produced by P. aeruginosa. This compound effectively impeded the cytochrome systems of various bacteria, including S. aureus19. While HQNO is recognized as an anti-staphylococcal agent, it does not induce lysis in S. aureus but retards its growth by inhibiting its oxidative respiration and ATP production.

HQNO is produced exclusively under aerobic conditions in the presence of oxygen20, suggesting that in the low-oxygen environments observed in thick S. aureus biofilms21,22, HQNO may have a limited role in mediating the interference between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Other documented anti-staphylococcal agents secreted by P. aeruginosa include pyocyanin4 and the LasA protease bacteriocin23. Considering our results, it is worth noting that P. aeruginosa may produce anti-staphylococcal agents regardless the environmental conditions. According to the literature, the number, quantity, and structure of these agents produced by P. aeruginosa can vary across different strains and growth conditions, such as planktonic versus biofilm states or in the presence of host factors and antibiotics. However, as attested in this work, these agents would only have mild bactericidal effectiveness against S. aureus once a mature biofilm is formed.

Antimicrobial activity tests

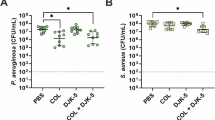

In order to assess whether the polymicrobial biofilm provides any advantage to bacteria against antimicrobial action, two different antimicrobials were selected to evaluate their effects on planktonic bacteria, as well as on single and mixed biofilms. The mixed biofilms were prepared following the methodology previously outlined in Fig. 2a and b. CHXD (1,6-bis(4-chloro-phenylbiguanido)hexane) was chosen as an example of a synthetic antiseptic commonly used in clinical settings whereas thymol (THY) (5-Methyl-2-(propan-2-yl)phenol) was chosen as an example of a natural origin antiseptic both used for skin disinfection. Results are represented in Fig. 5, while minimum biofilm inhibitory concentrations (MBIC) and minimum biofilm eradication concentrations (MBEC) data are summarized in Table 1.

Bactericidal activity of CHXD (a) and THY (b) against S. aureus Xen36 in planktonic, single-species biofilm and mixed biofilm formed with P. aeruginosa PAO1 after 24 h. Bactericidal activity of CHXD (c) and THY (d) against P. aeruginosa Lux in planktonic, single-species biofilm, and mixed biofilm formed with S. aureus 29213 after 24 h.

In this context, it was observed that, in the range of concentrations tested, CHXD effectively eliminated both bacterial species, with the exception of P. aeruginosa in its biofilm and mixed biofilm forms, as well as S. aureus in mixed biofilm. Notably, in the case of S. aureus within the mixed biofilm, its MBIC against CHXD also increased by a factor of 2.5 when compared with that obtained in its single biofilm form. On the other hand, THY displayed selective antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, not observing bactericidal activity against P. aeruginosa at the doses tested. THY successfully eradicated S. aureus in its planktonic state at concentrations above 600 mg/L, but it was less effective when forming either single or mixed biofilms. In the latter scenario, the MBIC of THY increased from 700 to 1000 mg/L when compared with its single biofilm form.

In summary, the interaction between bacterial species within the mixed biofilm conferred a survival advantage to S. aureus, enabling it to withstand the bactericidal effects of CHXD and resulting in an increased MBIC for both THY and CHXD. Previous studies have shown that the susceptibility of S. aureus to CHXD can differ in polymicrobial co-cultures24,25,26. It has been also reported that the presence of environmental selection pressure, such as antibiotics or the host immune system, stimulates a more synergistic relationship between different species and promotes biofilm formation. If S. aureus can withstand P. aeruginosa anti-staphylococcal activity and successfully coexists within a multi-species biofilm, it gains an advantage from the protective antimicrobial barrier created by the matrix components of P. aeruginosa27. Based on the experimental work conducted, it can be concluded that in a clinical scenario where there were a mixed biofilm involving at least these two species, it would be better not only to disperse the biofilm extracellular matrix formed but also to focus on selectively eliminating P. aeruginosa before addressing S. aureus. Infected wounds are clinically treated with antiseptics but in those cases that the infection might be extended to the bone (i.e., osteomyelitis) systemic and topical antibiotics might be used. When having a polymicrobial biofilm the selection of a wide spectrum antibiotic is key to assure that both pathogenic species would be eliminated from the wound bed.

Confocal microscopy studies

To further investigate the formation, interactions, and response to treatments within the established biofilm models, fluorescent bacterial strains (S. aureus GFP and P. aeruginosa BMP) were selected for their observation under confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). Single biofilms of S. aureus and mixed biofilms of S. aureus with P. aeruginosa were analyzed, with the latter biofilms being developed according to the strategy depicted in Fig. 2a. As observed in Fig. 6a and b, single S. aureus biofilms were established by day 2. By day 4, mixed biofilms were established with P. aeruginosa interpenetrating the existing S. aureus network. These mixed biofilms appeared to be thicker compared to their single S. aureus counterparts under the same conditions.

CLSM biofilm visualization: (a) Single S. aureus GFP biofilm and (b) Mixed S. aureus GFP / P. aeruginosa BFP biofilm. Biofilms were visualized on days 2, 4 and 5 after treatment with 10 mg/L or 40 mg/L of CHXD. S. aureus GFP is emitting in green, P. aeruginosa BFP in blue, and dead bacteria in red, regardless of the species. Images were constructed from the z-stack acquisition.

On day 5, single S. aureus biofilms exhibited a slight increase in their thicknesses compared to day 4 and remained discernible, primarily owing to the presence of GFP fluorescence. In contrast, within the mixed biofilms, S. aureus GFP cells were no longer distinguishable due to the suppressive effects on the GFP fluorescence caused by P. aeruginosa.

To reveal that S. aureus was no more visible on the mixed biofilm at day 5 due to reduction of GFP expression, another set of untreated mixed biofilms was grown under the same conditions as those depicted in Fig. 2a, but with the addition of Syto9 after PI (propidium iodide). Syto9 is a green fluorescent nucleic acid dye capable of penetrating cell membranes, enabling the staining of all bacterial cells both live and dead in the biofilm non-specifically, revealing S. aureus that were no longer visible (Fig. 7).

CLSM images of mixed biofilms observed on day 5: (a) Before the addition of SYTO-9, where P. aeruginosa is stained in blue, dead bacteria in red, and the signal of S. aureus (green) is not appreciable. (b) The same biofilm after the addition of SYTO-9, which labels all bacteria both live and dead in green, including S. aureus. Images below were constructed from the z-stack acquisition.

According to the images, it was found that P. aeruginosa was aggregated within the biofilms, thus located significantly on the top part of the biofilm, compared to S. aureus. Comparing the orthogonal projections of the same sample after the addition of SYTO-9 the thickness of the stained bacteria layer increased, which is an indication of the presence of S. aureus embedded in the matrix but preferentially located on top of the P. aeruginosa. This observation could confirm the reported non-random distribution pattern of these bacteria within chronic wounds. Typically, S. aureus tends to colonize the superficial layers of the wound, while P. aeruginosa is found in the deeper regions of the wound bed. This spatial differentiation in colonization has also been reported in previous studies28,29. Some studies propose that S. aureus and P. aeruginosa interact early during infection to maximize their chances of colonization and enhance virulence, as this initial collaboration supports their establishment. However, once colonization is secured, both virulence and cooperation diminish, leading the bacteria to segregate into distinct niches17.

Recent studies indicate that traditional swab culturing techniques may underestimate the presence of P. aeruginosa in wound infections30. Additionally, it aligns with the hypothesis that P. aeruginosa bacteria residing in the deeper regions of chronic wounds may play a pivotal role in maintaining wounds in a state characterized by inflammatory processes.

This work underlines the relevance of having polymicrobial populations and their microenvironment in the search of novel and effective treatments. It also highlights that the results obtained when evaluating an antimicrobial on planktonic bacteria or on single biofilms might be underestimated and the use of polymicrobial biofilms is recommended to mimic physiological settings.

Materials and methods

Materials

Thymol (THY, > 98.5%), chlorhexidine (CHXD, ≥ 99.5%), Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB), Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) and sodium chloride (NaCl, > 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (France). Three different S. aureus strains were used: S. aureus ATCC 29213; the bioluminescent S. aureus strain ATCC 49525 Xen36 (Perkin-Elmer, US); and a S. aureus strain expressing GFP (S. aureus-GFP; obtained using a pCN47 plasmid carrying a Phyper constitutive promoter as reporter of the GFP) originally from the laboratory of Dr. Iñigo Lasa and kindly donated by Dr. Cristina Prat (Institut d’Investigació en Ciències de la Salut Germans Trias i Pujol, Spain). The P. aeruginosa strains used were: P. aeruginosa PA01 ATCC 27853; a bioluminescent P. aeruginosa PA01 strain obtained by the chromosomal integration of the LuxCDABE operon (P. aeruginosa Lux), supplied by Prof. Patrick Plesiat (Centre National de Référence de la résistance aux antibiotiques, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Besançon, France); and a fluorescent P. aeruginosa PA01 (ATCC 27853) strain transfected with mCTXtagBFP2, which expresses BFP (P. aeruginosa-BFP, blue fluorescence).

Development of polymicrobial co-cultures

To obtain fresh liquid cultures of bacteria, isolated colonies of the tested strains were dispersed in 10 mL of MHB and incubated for 24 h under shaking at 37 °C. To produce a polymicrobial biofilm including the two bacterial species, two distinct microbiological strategies were used.

In the first strategy, a liquid culture of planktonic S. aureus (Xen36 or ATCC 29213) was diluted with fresh MHB to obtain ~ 107 colony forming units (CFU)/mL (OD600 ≈ 0.006). Then, 100 µL of the bacterial suspension were added to the wells of white, flat-bottom 96-well microplates. The luminescence of wells containing S. aureus Xen36 was recorded over time using a microplate reader (Infinite M200 Pro, Tecan®, Männedorf, Switzerland) until a value of around 1,000 relative light units (RLU) was reached, which allowed an increase or decrease in RLU to be detected later with good sensitivity. Next, 100 µL of bacterial suspension containing increasing concentrations (101 to 108 CFU/mL) of planktonic P. aeruginosa Lux or P. aeruginosa PAO1 were added to the wells. To ensure that the bioluminescent signal was originated solely from only one of the two species, P. aeruginosa Lux was added to non-luminescent S. aureus ATCC 29213, while P. aeruginosa PAO1 was added to luminescent S. aureus Xen36. A visual representation of the experimental design is shown in Fig. 8a and b. After the addition of P. aeruginosa to S. aureus, the plates were sealed with a clear gas-permeable hydrophobic membrane (4titude Ltd, Surrey, UK) to prevent evaporation, and luminescence was recorded every 30 min for 48 h at 37 °C. Finally, the wells were carefully scraped and washed with 1 mL 0.9% (w/v) NaCl to harvest bacteria, which were serially diluted in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl and spread on two different agar media to obtain accurate bacterial counts of both species. MHA supplemented with colistin (8 mg/L) was used for the selective growth of S. aureus, and normal MHA for the growth of both species.

In the second approach, 100 µL of S. aureus suspensions (Xen36 or ATCC 29213) at 107 CFU/mL were added to the wells of a white, flat-bottom, high-binding 96-well microplates. Plates were sealed with a hydrophobic gas-permeable membrane and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C under shaking. After biofilm formation, supernatants were removed, and the wells were washed 3-times with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl. Next, 100 µL of fresh MHB were added, and the bioluminescence was recorded until an intensity of around 1,000 RLU was achieved. Then, suspensions with increasing concentrations (101 to 108 CFU/mL) of P. aeruginosa (Lux or PAO1) were added to the wells, as depicted in Fig. 8c and d. The microplates were then sealed with a clear gas-permeable hydrophobic membrane, and the luminescence was recorded every 30 min for 48 h at 37 °C. Finally, to collect the bacterial biofilms, the wells were carefully scraped, sonicated, and washed with 1 mL 0.9% (w/v) NaCl to harvest the bacteria, which were then serially diluted and seeded to count colonies.

Schematic overview of the strategies used to obtain polymicrobial biofilms: (a) and (b) schemes represent the first methodology, where the co-culture was established by adding the bacterial species in their planktonic state. (c) and (d) schemes depict the second methodology used, involving the addition of P. aeruginosa in the planktonic state to a pre-formed 48 h old S. aureus biofilm.

Study of the interaction between S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in mixed biofilm

To further investigate the interaction between S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, a Transwell® system having a 0.4 μm pore size polycarbonate membrane (Corning, France) was used to spatially separate both species. In brief, single biofilms of bioluminescent S. aureus Xen36 and mixed biofilms composed of S. aureus Xen36 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 were established at the bottom of 24-well plates using the strategy described in Fig. 8c. To form the mixed biofilms, 1 mL of P. aeruginosa PAO1 suspension at 104 CFU/mL was inoculated onto 48 h old S. aureus Xen36 biofilms. On the other hand, the same mixed biofilms (S. aureus Xen36 and P. aeruginosa PAO1) or single PAO1 biofilms were formed onto Transwell® inserts as described above. Biofilms were then washed with 0.9% NaCl and fresh MHB was added (0.6 mL in the wells and 0.1 mL in the inserts). The inserts were placed in the wells and bioluminescence emitted by S. aureus Xen36 at the bottom of the wells was recorded at different times over 48 h using a microplate reader. At the end of the experiments, biofilms were disrupted via sonication, serially diluted, and plated on MHA to quantify S. aureus CFUs present in the wells.

To determine whether P. aeruginosa was capable of secreting molecules interfering with the metabolic activity of S. aureus without being in direct contact or in proximity to it, a medium in which P. aeruginosa PAO1 had been cultured alone was collected and added to S. aureus biofilms. For this study, a mutant strain of S. aureus that expresses the green fluorescent protein (S. aureus GFP) was used. To obtain this conditioned medium (CM), 1.5 mL of P. aeruginosa PA01 at 104 CFU/mL were seeded on top of 6-well Transwell® inserts placed in wells containing 2.6 mL of MHB and incubated in a water-saturated incubator at 37 °C. Three days later, the medium under the insert was collected, centrifuged twice at 13,000 g for 5 min and filtered through a 0.22 μm filter to remove any potential PAO1 bacteria present. This CM was then serially diluted and deposited on 48 h old S. aureus GFP biofilms grown in 96-well plates as explained above. S. aureus GFP fluorescence was then measured at 488 nm after excitation at 520 nm every hour for 72 h at 37 °C using a microplate reader.

In vitro antimicrobial activity tests

Antimicrobial activity of THY and CHXD was tested against S. aureus Xen36 and P. aeruginosa Lux in planktonic state as well as when forming single and mixed biofilms.

To run tests against planktonic cultures, fresh bacterial cultures were adjusted to 107 CFU/mL and 100 µL of the suspensions were added to the wells of white 96-well microplates. The bioluminescence of the wells was recorded over time (2–3 h) until reaching 1,000 RLU for S. aureus Xen36 and 10,000 RLU for P. aeruginosa Lux, which is more luminescent than S. aureus Xen36. Then, MHB solutions with increasing concentrations of CHXD (0.4 to 40 mg/L) and THY (400 to 1,000 mg/L) were added to reach a final volume of 200 µL. Next, the plates were sealed with an optical clear membrane and the luminescence was recorded every 30 min for 24 h at 37 °C. Finally, the cultures in the wells were seeded on MHA plates after serial dilution for CFU counting.

Regarding the experiments on single biofilm-forming bacteria, 100 µL of bacterial suspensions at 107 CFU/mL were added to the wells of high-binding 96-well white microplates, which were then sealed with a gas-permeable membrane and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C with agitation. After incubation, MHB was removed, and biofilms were washed with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl before adding 100 µL of fresh MHB. The bioluminescence of the wells was then adjusted to the same values as the ones used for planktonic cultures (~ 1,000 RLU for S. aureus Xen 36, ~ 10,000 RLU for P. aeruginosa Lux). CHXD and THY treatments were also added to obtain the same concentrations as the ones used for evaluating the antimicrobial activity tests on planktonic bacteria (0.4 to 40 mg/L for CHXD and 400 to 1,000 mg/L for THY). Finally, the wells were thoroughly scraped and rinsed before serial dilution of the samples and plating them to quantify CFUs.

Mixed biofilm-forming bacteria assays were performed using suspensions containing 104 CFU/mL of planktonic P. aeruginosa PAO1 and planktonic P. aeruginosa Lux, which were added to pre-formed 48 h old biofilms of S. aureus Xen36 and S. aureus ATCC 29213, as described in the previous section. These co-cultures were incubated again for 48 h to form the mixed biofilms before being washed with 0.9% (w/v) NaCl and before the addition of CHXD and THY treatments, as described previously for the individual biofilm activity tests. Lastly, mixed biofilms were dispersed, serially diluted, and plated on selective (colistin-supplemented MHA) and non-selective (regular MHA) agar plates to quantify CFUs.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy studies

Single and mixed biofilms composed of the fluorescent S. aureus GFP and P. aeruginosa-BFP (Blue Fluorescent Protein) were grown on 8-well µ-slide chambers (Ibidi GmbH, Germany) enabling their spatial organization to be assessed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). The strategy used for biofilms formation was identical to that described Fig. 8c, but fluorescent strains were used instead of the luminescent one. Briefly, 300 µL of S. aureus-GFP at 107 CFU/mL were added to the chamber wells and incubated under shaking for 48 h at 37 °C in a water-saturated atmosphere for S. aureus biofilm formation. S. aureus biofilms were then washed and supplemented with MHB or 104 CFU/mL of P. aeruginosa BFP suspension and incubated again for 48 h under the same conditions. Then, biofilms were washed and supplemented with different treatments (MHB, or MBH containing either CHXD 10 mg/L or 40 mg/L) and re-incubated for 24 h. The wells were then washed 3 times and filled with 300 µL of 0.9% NaCl containing propidium iodide (PI) at 20 µM. Some mixed biofilms were also labelled with 5 µM SYTO-9, a fluorescent probe that labels both live and dead bacteria in green.

At different times (2, 4 and 5 days), biofilms were visualized under an Olympus FluoView FV-3000 with an IX83 CLSM (x100 zoom). For each biofilm, samples were sequentially excited to study the fluorescence of GFP or SYTO-9 (excitation 488 nm - emission 500/540 nm), BFP (excitation 405 nm - emission 430/470 nm), and PI (excitation 561 nm - emission 570/670 nm). Twenty to thirty stacks of horizontal plane images (1024 × 1024 pixels corresponding to 127 × 127 μm) with a z-step of 0.5 μm were acquired for each condition. Three-dimensional biofilm projections were constructed using the Easy 3D function of the IMARIS software (Bitplane). When creating the surfaces, the same segmentation parameters (particle size, absolute intensity and absence of post-segmentation filters) were applied to all 3D constructs.

Conclusion

The monitoring of co-cultures using bioluminescent, fluorescent and wild type bacterial strains, in order to develop a polymicrobial mixed biofilm, was successful. Notably, P. aeruginosa was able to secrete molecules that repress S. aureus metabolism and protein synthesis without requiring physical contact or the presence of both species in the same environment.

In mixed biofilms, the interaction between the two bacterial species provided S. aureus with a survival advantage, making it less susceptible to the bactericidal effects of CHXD and resulting in elevated MBIC values for both THY and CHXD. Lastly, the non-random spatial organization of the bacterial species observed within the mixed biofilm had similarity with previous reports on co-infected chronic wounds. This alignment underscores the importance of bacterial crosstalk in polymicrobial cultures and highlights the potential implications for understanding and managing polymicrobial wound infections to select the most appropriate antimicrobial regime.

Data availability

The data will be available from the corresponding authors after reasonable request.

References

Yung, D. B. Y., Sircombe, K. J. & Pletzer, D. Friends or enemies? The complicated relationship between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 116, 1–15 (2021).

Pastar, I. et al. Interactions of Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Polymicrobial Wound infection. PLoS One 8, e56846, 1–11 (2013).

Baldan, R. et al. Adaptation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic Fibrosis airways influences virulence of Staphylococcus aureus in Vitro and Murine models of Co-infection. PLoS One. 9, e89614 (2014).

Biswas, L., Biswas, R., Schlag, M., Bertram, R. & Götz, F. Small-colony variant selection as a Survival Strategy for Staphylococcus aureus in the Presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 6910–6912 (2009).

Hoffman, L. R. et al. Selection for Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants due to growth in the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103, 19890–19895 (2006).

Antonic, V., Stojadinovic, A., Zhang, B., Izadjoo, M. J. & Alavi, M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa induces pigment production and enhances virulence in a white phenotypic variant of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Drug Resist. 6, 175–186 (2013).

Maliniak, M. L., Stecenko, A. A. & McCarty, N. A. A longitudinal analysis of chronic MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa co-infection in cystic fibrosis: a single-center study. J. Cyst. Fibros. 15, 350–356 (2016).

Leid, J. G. et al. The Exopolysaccharide Alginate protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilm Bacteria from IFN-γ-Mediated macrophage killing. J. Immunol. 175, 7512–7518 (2005).

Cohen, T. S. et al. Staphylococcus aureus α toxin potentiates opportunistic bacterial lung infections. Sci. Transl Med. 8, 329ra31, 1–11 (2016).

Michelsen, C. F. et al. Evolution of metabolic divergence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa during long-term infection facilitates a proto-cooperative interspecies interaction. The ISME Journal 10, 1323–1336 (2015).

DeLeon, S. et al. Synergistic interactions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus in an in vitro wound model. Infect. Immun. 82, 4718–4728 (2014).

Gounani, Z., Şen Karaman, D., Venu, A. P., Cheng, F. & Rosenholm, J. M. Coculture of P. Aeruginosa and S. Aureus on cell derived matrix - an in vitro model of biofilms in infected wounds. J. Microbiol. Methods. 175, 105994 (2020).

Woods, P. W., Haynes, Z. M., Mina, E. G. & Marques, C. N. H. Maintenance of S. aureus in co-culture with P. aeruginosa while growing as Biofilms. Front. Microbiol. 9, 3291, 1–9 (2019).

Kumar, A. & Ting, Y. P. Presence of < scp > P seudomonas aeruginosa influences biofilm formation and surface protein expression of < scp > S taphylococcus aureus. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 4459–4468 (2015).

Radlinski, L. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoproducts determine antibiotic efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Biol. 15, e2003981 (2017).

Hotterbeekx, A., Kumar-Singh, S., Goossens, H. & Malhotra-Kumar, S. In vivo and In vitro interactions between Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus spp. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 7, 106, 1–13 (2017).

Alves, P. M. et al. Interaction between Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa is beneficial for colonisation and pathogenicity in a mixed biofilm. Pathog Dis. 76, 1–10 (2018).

Lightbown, J. W. & Jackson, F. L. Inhibition of cytochrome systems of heart muscle and certain bacteria by the antagonists of dihydrostreptomycin: 2-alkyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N -oxides. Biochem. J. 63, 130–137 (1956).

Williams, P. & Cámara, M. Quorum sensing and environmental adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a tale of regulatory networks and multifunctional signal molecules. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 12, 182–191 (2009).

Beaume, M. et al. Metabolic pathways of Pseudomonas aeruginosa involved in competition with respiratory bacterial pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 6, 138664 (2015).

Pabst, B., Pitts, B., Lauchnor, E. & Stewart, P. S. Gel-entrapped Staphylococcus aureus bacteria as models of biofilm infection exhibit growth in dense aggregates, oxygen limitation, antibiotic tolerance, and heterogeneous gene expression. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 6294–6301 (2016).

Cotter, J. J., O’Gara, J. P. & Casey, E. Rapid depletion of dissolved oxygen in 96-well microtiter plate Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilm assays promotes biofilm development and is influenced by inoculum cell concentration. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 103, 1042–1047 (2009).

Kessler, E., Safrin, M., Olson, J. C. & Ohman, D. E. Secreted LasA of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a staphylolytic protease. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 7503–7508 (1993).

Townsend, E. M. et al. Development and characterisation of a novel three-dimensional inter-kingdom wound biofilm model. Biofouling. 32, 1259–1270 (2016).

Touzel, R. E., Sutton, J. M. & Wand, M. E. Establishment of a multi-species biofilm model to evaluate chlorhexidine efficacy. J. Hosp. Infect. 92, 154–160 (2016).

Kart, D., Tavernier, S., Van Acker, H., Nelis, H. J. & Coenye, T. Activity of disinfectants against multispecies biofilms formed by Staphylococcus aureus, Candida albicans and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biofouling. 30, 377–383 (2014).

Billings, N. et al. The Extracellular Matrix Component Psl provides fast-acting Antibiotic Defense in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003526 (2013).

Serra, R. et al. Chronic wound infections: the role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 13, 605–613 (2015).

Pouget, C. et al. Polymicrobial Biofilm Organization of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in a chronic Wound Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 10761 (2022).

Kirketerp-Møller, K. et al. Distribution, Organization, and Ecology of Bacteria in chronic wounds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 2717–2722 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant numbers PID2020-113987RB-I00 and PDC2021-121405-I00) for funding. G.L. acknowledges the support from the FPI program (PRE2018-085769, Spanish Ministry of Science, and Innovation). G.M. gratefully acknowledges the support from the Miguel Servet Program (MS19/00092; Instituto de Salud Carlos III). A portion of the schemes depicted in figures were created with the assistance of BioRender.com.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: F.T.; Methodology: G.L., J.C. and J.B.; Formal analysis: G.L., F.T.; Investigation: G.M., M.A. and F.T.; Writing original draft: G.L. and G.M.; Writing, Review and Editing: J.C., J.B., M.A. and F.T.; Supervision: G.M., M.A. and F.T.; Funding acquisition: M.A.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Landa, G., Clarhaut, J., Buyck, J. et al. Impact of mixed Staphylococcus aureus-Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm on susceptibility to antimicrobial treatments in a 3D in vitro model. Sci Rep 14, 27877 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79573-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79573-y