Abstract

Inflammatory microenvironments often become acidic (pH < 7.4) due to tissue oxygen deprivation and lactate release in glycolysis by activated immune cells. Although neutrophils are known to accumulate in such microenvironments, the effects of pH on their migration are not fully understood. Here, we first investigated the pH control around cultured cells with a microfluidic device, which was equipped with two gas channels above three parallel media channels. By supplying gas mixtures with predefined carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations to the gas channels, the gas exchange adjusted the dissolved CO2 and affected the chemical equilibrium of sodium hydrogen carbonate in the cell culture medium. A pH gradient from 8.3 to 6.8 was generated along the media channels when gas mixtures containing 1% and 50% CO2 were supplied to the left and right gas channels, respectively. Neutrophil-like differentiated human promyelocytic leukemia cells (HL-60) were then seeded to the fibronectin-coated media channels and their migratory behaviors were quantified while varying the pH. The cell migration became more active and faster under high pH than under low pH conditions. However, no directional migration along the pH gradient was detected during the three-hour observation. Thus, the microfluidic device is useful to elucidate pH-dependent cellular dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Leukocytes that eliminate pathogens play a major role in the immune response against infection and viruses. Leukocytes can be classified into five types: neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes1. Neutrophils, which account for 40–60% of all circulating leukocytes, can eliminate pathogens through multiple mechanisms and are the first line of defense cells in the innate immune system2. A significant decrease in neutrophils in the blood leads to problems such as severe immunodeficiency and death2,3. Neutrophils are sensitive to stimuli and can reach the site of inflammation or tissue damage in large numbers within minutes, and they are known to exhibit chemotaxis, sensing a concentration gradient of chemicals in the environment around the cells and migrating to areas of higher concentration4. During acute inflammation, they are activated by chemokines secreted by cells, adhere to the vascular endothelial cell layer, and migrate according to the chemokine concentration gradient2. Neutrophils then transmigrate across the vascular endothelial cells and migrate to inflammatory sites by sensing a concentration gradient of inducible factors such as bacterial-derived formylpeptide and complement component C5a2,5,6. Neutrophils can also migrate to tumor sites induced by chemokines secreted by tumor-forming cancer cells7. Thus, neutrophil behavior is differentially affected by various physiological conditions and complex scenarios in the microenvironment. Understanding the behavior of neutrophils is essential for elucidating and regulating immune responses to changes in the in vivo microenvironment, such as individual infections and complex inflammatory disease states.

The pH in human tissues is maintained in the range of about 7–7.4 with small fluctuations, with some exceptions (e.g., pH 1–3 in the stomach and pH 4–7 in the small intestine). In particular, the pH in serum must be tightly controlled at about 7.4 for human survival, and deviations from the blood pH of 7.3–7.45 tend to be small8. This pH in the body is regulated by various biological mechanisms, such as the respiratory and renal systems9. However, inflammatory microenvironments often become acidic due to tissue oxygen deprivation and lactate release10,11. The tumor microenvironment is also acidified by excessive production of lactic acid and carbonic acid due to activation of the glycolytic system12. For example, it has been reported that extracellular pH decreases to about 6.8 in human breast cancer tissue8. Decreased extracellular pH delays neutrophil apoptosis and affects immune and bactericidal responses10. It has also been reported to cause insulin resistance in skeletal muscle cells and increase the risk of developing cancer and cardiovascular disease9. On the other hand, an increase of blood pH to be > 7.45 due to metabolic and respiratory disorders is defined as alkalosis, affecting homeostasis13,14. As described above, cell behavior is related to pH in the in vivo microenvironment, but a detailed understanding of the relationship has not been achieved.

To reproduce the in vivo pH environment in vitro, HEPES-buffered Ringer’s solution, hydrogen chloride, or 0.1% acetic acid have been added to cell culture medium containing sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO3)10,11,15. In these techniques, the pH is adjusted by changing the volume of carbon dioxide (CO2) dissolved in the cell culture medium, using a chemical equilibrium centered on NaHCO316,17. The pH can also be controlled by placing the medium in an environment with a controlled CO2 concentration. Normally, when incubating cells, the CO2 concentration inside the incubator is kept at 5% to maintain the pH of the cell culture medium at 7.418. However, the incubator method has difficulty in generating a pH gradient in a microenvironment.

Recently, microfluidic devices have been used to study cellular dynamics. Microfluidic devices generally fabricated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a transparent and highly gas permeable polymer, have micro-sized channels. Cells can be cultured in the microchannels and observed in real time under strict control of various environmental factors. We have developed microfluidic devices that reproduce hypoxic conditions in vivo by controlling oxygen concentration to elucidate oxygen-dependent cell dynamics19,20,21. By supplying gas mixtures at preadjusted oxygen concentrations to the gas channels, the oxygen concentration in the device can be controlled by means of gas exchange between the cell culture medium and the supplied gas mixture through PDMS. Experiments with cancer cells19,21 and Dictyostelium discoideum20 using the developed device have shown that the migration speed of these cells increased in hypoxic environments and that they undergo aerotaxis, migrating from hypoxic regions to normoxic regions. In addition, microfluidic devices that can control pH are being developed22. By supplying a liquid of a certain pH into a gel-filled channel in the device, the pH can be controlled by permeation of the liquid into the gel. Studies have been conducted on the pH dependence of Serratia using this device, which showed a tendency to migrate from excessively acidic or alkaline regions to neutral regions under a pH gradient22.

In this study, we examined the behavior of neutrophils in response to pH. We attempted to control the pH of microenvironments through gas exchange and chemical equilibrium in a previously developed microfluidic device with controllability of oxygen concentration (Fig. 1). We measured the pH of the cell culture medium when gas mixtures with a controlled CO2 concentration were blown against the medium and determined the relationship between the CO2 concentration and pH. Using uranine, which changes fluorescence intensity according to pH23, pH control in the media channel in the device was validated when gas mixtures with adjusted CO2 concentrations were supplied to the gas channel. Moreover, we observed the migration of neutrophil-like human promyelocytic leukemia line cells (HL-60 cells) while controlling pH. Under the pH gradient from 8.3 to 6.8, the migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells was found to decrease at low pH (< 7.4).

Results

Variation in pH by dissolved CO2 concentration in the cell culture medium

Theoretical analysis of pH in the cell culture medium based on the chemical equilibrium equation showed that the higher the CO2 concentration, the lower the pH (Fig. 2). The pH of the cell culture medium in the centrifuge tube became constant approximately 2 h after blowing each gas mixture with adjusted CO2 concentration. Consistent with the theoretical estimation, as the CO2 concentration in the gas mixture blown against the cell culture medium increased, the pH decreased. The pH in the cell culture medium RPMI-1640, which is normally used for cell cultures of human leukemia cell lines, was 7.7 with the 5% CO2 gas mixture. The pH decreased to 6.9 with the 50% CO2 gas mixture and increased to 8.4 with the 1% CO2 gas mixture. Here, under 0% CO2, the pH in the medium appeared to be > 9.5, but could not be measured due to the upper limit of the optical pH sensor. Based on the measured values, a logarithmic approximation of the relationship between pH and CO2 concentration, catm, in the supplied gas mixture yielded the following equation:

Comparison of the measured and theoretical values showed a large deviation between the two values with increasing CO2 concentration in the gas mixture blown against the cell culture medium. This may be because the theoretical analysis was performed assuming low CO2 concentration, and did not take into account the effects of other chemicals such as FBS added to the cell culture medium, and the existence of chemical equilibrium by buffer systems other than NaHCO3. Therefore, Eq. (1) obtained by actual measurements was adopted as the equation to relate the CO2 concentration in the cell culture medium to pH, and was used in the pH measurement of the cell culture medium in the media channel based on the fluorescence intensity of uranine, as described later.

CO2 concentration and pH control by microfluidic device

Numerical simulation revealed changes in the CO2 concentration in the media channels when gas mixtures with predefined CO2 concentrations were supplied to both gas channels (Fig. 3). The supply of 1% CO2 gas mixture to both gas channels generated a uniform CO2 concentration of approximately 1.1% CO2 in the media channels, while the supply of 50% CO2 gas mixture generated a uniformly high CO2 concentration of approximately 49% CO2. The supply of gas mixtures of 1% and 50% CO2 to the left and right channels, respectively, generated a linear CO2 concentration gradient of approximately 1.3–48% CO2 along the media channels between the positions of the two gas channels.

Computational results of steady CO2 concentration in the microfluidic device placed in a stage incubator controlled at 5% CO2. (a) CO2 distributions on a horizontal cross section (z = 0 mm), generated by supplying gas mixtures containing 1, 5, 20, or 50% CO2 to both gas channels for uniform CO2 conditions, or by supplying gas mixtures with 1% and 50% CO2 to the left- and right gas channels, respectively for a CO2 gradient. (b) CO2 concentration profiles along the center line of the media channel (y = 0 mm, z = 0 mm) under different CO2 conditions. The variables cL and cR indicate the CO2 concentration in the gas mixtures supplied to the left and right gas channels, respectively.

Fluorescence microscopy images were obtained under CO2 control by injecting a cell culture medium containing uranine into the media channels (Fig. 4a). The higher the CO2 concentration in the gas mixture supplied to the gas channels, the lower the fluorescence intensity of the uranine, indicating the lower pH. In each 100 µm × 100 µm area in the ROI along the media channels (see Fig. 1b), the fluorescence intensity \(\overline{I }\) under each condition was normalized by dividing it by the intensity under the 5% CO2 condition, \({\overline{I} }_{5}\) (Fig. 4b). Uniform fluorescence intensity distributions were observed in the media channel when the same gas mixtures were supplied to both gas channels, whereas a fluorescence intensity gradient was observed along the media channel when gas mixtures at different CO2 concentrations were supplied to the left and right gas channels. The relationship between fluorescence intensity and pH was then approximated exponentially, using the relative fluorescence intensities at 5, 20, and 50% CO2 (Fig. 4c). Subsequently, the pH distribution under the CO2 concentration gradient was calculated (Fig. 4d), and the CO2 concentration distribution was also estimated based on Eq. (1). Consequently, the pH gradient from 8.3 to 6.8 was generated along the media channels when gas mixtures at 1% and 50% CO2 were supplied to the left and right gas channels, respectively.

Validation results of pH distribution controlled by dissolved CO2 in the cell culture medium in the media channel. (a) Representative fluorescence microscopy images of cell culture medium containing uranine. The uniform CO2 conditions were generated by supplying gas mixtures containing 5, 20, or 50% CO2 to both gas channels and the stage incubator for reference. The CO2 gradient was generated by supplying gas mixtures with 1% and 50% CO2 to the left and right gas channels, respectively, and 5% CO2 to the stage incubator. (b) Representative fluorescence intensity ratio \(\overline{I }/{\overline{I} }_{5}\) relative to 5% CO2 condition. (c) Relationship between relative fluorescence intensity ratio and pH of the cell culture medium containing uranine. (d) CO2 concentration and pH gradients generated in the media channels (mean ± S.D., n = 3). The variables cL, cR, and catm indicate the CO2 concentration in the gas mixtures supplied to the left gas channel, the right gas channel, and the stage incubator, respectively.

Changes in migratory behaviors of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells under controlled pH

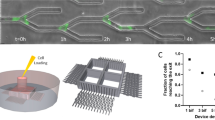

HL-60 cells differentiated into neutrophil-like cells were seeded into fibronectin-coated media channels, and their behavior under pH-controlled conditions (see Table 3) was investigated by analyzing sequential microscopic images. Representative phase-contrast microscopy images of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells before and after 3 h observation under the pH gradient, and cell migration trajectories drawn by setting the initial position of each cell at the origin in the subdivided regions A1–A5, are shown in Fig. 5a. The cells were more active on the high pH side (regions A1 and A2) than the low pH side (regions A4 and A5). However, the migration was random in all regions, showing no directional migration along the pH gradient. The migration speed measured in each region dividing the ROI every 200 µm in the x-direction increased after 1 h, and was smaller on the low pH side than on the high pH side in all time periods (Fig. 5b). Classification of the migration speed of cells between 2 and 3 h by 2 µm/min in each subdivided region A1–A5 indicated that the population of fast migrating cells was larger on the high pH side (regions A1 and A2) than on the low pH side (regions A4 and A5) (Fig. 5c). The directionality of migration was evaluated by decomposing the migration speed into x- and y-directional velocity components, u and v, which are parallel and perpendicular to the pH gradient, respectively (Fig. S1a). There was no significant change between the high and low pH sides, or in the directionality of migration according to the pH gradient.

Measurement of migration of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells with the microfluidic device placed in a stage incubator controlled at 5% CO2. (a) Representative phase-contrast microscopy images of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells before and after the 3-h experiment under a pH gradient, and migration trajectories of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells over the period. (b) Temporal and spatial variations in average migration speed of the cells under the pH gradient (mean ± S.D., n = 3). (c) Stacked bar chart of migration speed in the subdivided regions A1–A5 between 2 and 3 h after the experiment under the pH gradient. (d) Spatial variation in average migration speed of the cells between 2 and 3 h after the experiment under the uniform pH conditions and the pH gradient and (e) variation in the migration speed with pH (mean ± S.D., n = 3). (f) Box-and-whisker plots of persistence of the migration direction between 2 and 3 h after the experiment under the uniform pH conditions and the pH gradient. The upper and lower extremes represent the 90th and 10th percentiles, the box plot represents quartiles, and the open square and circle inside each box show the average and the median values, respectively. The variables cL and cR indicate the CO2 concentration in the gas mixtures supplied to the left and right gas channels, respectively. Significant differences in persistence were assessed by the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

To further investigate the behavior of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells in response to pH, the cell migration was measured under uniform pH conditions (pH 6.8, 7.6 and 8.3) by supplying gas mixtures of 50, 5, and 1% CO2 concentration to the gas channels, respectively (Fig. 5d). Under all pH conditions, as observed in the experiment with the pH gradient, cell motility became active 1 h after the start of the experiment. The migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells between 2 and 3 h after the start of the experiment was 3.0 µm/min under a uniform pH of 7.6 generated with 5% CO2, and was similar for pH 8.3. In contrast, at lower pH 6.8, the migration speed decreased to 1.6 µm/min, which was about half that at pH 7.6. The summary of cellular experiments under uniform pH and a pH gradient indicated a linear correlation in migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells with pH between 8.3 and 6.8 (R2 = 0.95, Fig. 5e). Persistence of the cell migration direction was examined by the ratio of the total length of the cell migration trajectory to the distance between the initial and final points between 2 and 3 h under each pH condition, focusing on the regions A2-A4 where pH gradient was generated (Fig. 5f). The persistence values ranged from 0.1 to 0.2 under all pH conditions, but tended to be larger under high pH condition (low CO2 condition) than under low pH condition (high CO2 condition). Here, the persistence of the migration direction in the regions A1 and A5 was almost the same as that in the regions A2 and A4, respectively, as the pH levels were similar.

The pH-dependent migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells was increased by supplementation of chemical materials (Fig. 6). Chemical stimulation of a complement by adding N-Formyl-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) to the cell culture medium accelerated the cell migration especially under acid region (Fig. 6a), but the migration speed still showed a pH-dependent variation with a larger value under a high pH region (Fig. 6d). Moreover, addition of sodium pyruvate or cariporide to the cell culture medium also enhanced the cell migration (Fig. 6b,c), while maintaining the linear correlation in migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells with pH between 8.3 and 6.8 (Fig. 6d). The x-directional velocity tended to show negative values at the region with pH gradient, implying cell migration toward the alkalic region, but the directional migration along the pH gradient was not clear enough (Fig. S1). The average migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells at three different pH levels (pH 8.32, 7.56, and 6.86 at x = − 1.4, 0, and 1.4 mm, respectively) under a pH gradient without/with chemical stimuli was summarized (Fig. S2) and statistically analyzed. The results indicated that the cell migration speed under the control condition was significantly lower than that in the presence of fMLP (P < 0.005), pyruvate (P < 0.001), or cariporide (P < 0.005). In addition, the cell migration speed at pH 8.32 was significantly different from that observed at the other pH levels (P < 0.001).

Measurement of migration of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells under a pH gradient with chemical stimuli by using the microfluidic device placed in a stage incubator controlled at 5% CO2. Temporal and spatial variations in average migration speed of the cells under the pH gradient with supplementation of (a) 10 nM fMLP, (b) 1 mM pyruvate sodium, or (c) 10 µM cariporide (mean ± S.D., n = 3), and (d) variation in the migration speed with pH between 2 and 3 h after the experiment under the pH gradient with/without the chemical stimuli.

Discussion

The pH control of the cell culture medium in the microfluidic device was achieved by adjusting the dissolved CO2 through gas exchange and by manipulating the chemical equilibrium of NaHCO3. The behavior of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells was found to be pH-dependent, with increased migration in high pH environments and suppressed migration in low pH environments. However, the direction of migration was not affected by the pH gradient in the present study.

By adjusting the components in the gas mixtures supplied to the gas channels, the CO2 concentration in the cell culture medium in the adjacent media channels across the PDMS membrane could be controlled owing to the high gas permeability of PDMS (Fig. 3). The chemical equilibrium centered on NaHCO3 was shifted by changing the CO2 concentration in the cell culture medium; the pH of the cell culture medium decreased with increasing dissolved CO2 (Fig. 2). The pH distribution was validated with the fluorescence intensity of uranine solution filled in the media channel, showing that a pH gradient from pH 8.3 to 6.8 was generated when gas mixtures of 1% and 50% CO2 were supplied to the left and right gas channels, respectively (Fig. 4). In previous studies, the pH was adjusted by adding HEPES-buffered Ringer’s solution, hydrogen chloride, or acetic acid to cell culture media containing NaHCO3 to reproduce in vivo pH environments in vitro10,11,15. Chambers that control permeation of solutions at two different pHs22,24,25 and cell metabolism26 have also been utilized to generate pH gradients. Compared with the previous devices, the present microfluidic device can generate pH gradients between pH 8.3 and 6.8 in a microenvironment more easily and precisely.

The experimental and numerical results of the CO2 concentration and pH level showed good agreement at both ends of the media channel (Fig. 4d). However, the pH gradient was slightly gentler in the computational result than in the experimental one, and the position of the gradient was also shifted between the two. This might be due to inaccuracies in setting parameters such as the diffusion coefficient and solubility of CO2 in each material assumed in the numerical simulation. The presence of components other than NaHCO3 in the cell culture medium might affect the control of dissolved CO2 and protons. Other reasons include limitations in the performance of the experimental setup, such as leakage of CO2 or permeation of atmospheric gas components while the gas mixtures traveled from the gas blender to the apparatus, shortage in supply of gas mixture to the gas channels and stage incubator during measurement of fluorescence at reference CO2 concentrations, and temperature change by supply of gas mixtures. Improvement of the experimental setup to eliminate these effects will be subjects for future study.

The developed microfluidic device enabled real-time observation of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells under pH-controlled conditions (Fig. 5). Migration of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells was fast in the high pH region with few slow-moving cells, whereas it was slow in the low pH region, indicating suppression of cell motility. The measured cell migration speed was around one-third to one-fifth of those reported in the previous papers27,28,29. This could be caused by cell differentiation methods; ATRA and DMSO, leading to different expressions of glycoproteins like CD11b and CD14 on cell membrane30,31. The fibronectin coating on the media channels and experimental condition without a chemical gradient inducing chemotaxis could also be attributed to the slow migration speed. Interestingly, a linear correlation was confirmed between pH and the migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells under the pH gradient (Fig. 5e). However, the cells showed random migration, and no clear directional migration along the pH gradient was observed during the short observation (Fig. S1). The consistency of migration direction tended to be less at low pH (Fig. 5f), indicating higher probability of random changes or large angle changes in migration direction. Previous studies revealed that the migration of mouse and human neutrophils was affected by extracellular pH and migration was inhibited at low pH27,32. In addition, mouse neutrophils reportedly exhibited directional migration under a pH gradient27. Consistent with these studies, the present study showed that a low pH environment suppressed the migration of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells, but no directionality of migration along the pH gradient was observed during the three-hour observation. The migration speed was increased by the supplementation of fMLP, and still showed a pH-dependent variation with an increase under a high pH region (Fig. 6a,d). Consequently, the neutrophil-like HL-60 cells have the characteristics to increase their migration speed under high pH condition regardless of chemical stimulus by a complement.

To our knowledge, the HL-60 cells do not have specific receptors dedicated to detecting proton (H+) or changes in H⁺ concentration. However, they can respond to changes in pH through general cellular mechanisms, such as ion channels and transporters that regulate intracellular pH, proteins that change conformation and function by pH changes, and cellular metabolism33,34. The explanation for the decreased migration speed under a low pH by energy consumption for maintenance ionic balance and pH homeostasis seems to be plausible. Ion channels and transporters that regulate intracellular pH use ATP to transport ions across the cell membrane. In addition, the cells might also need to repair damage caused by the low pH, further increasing their energy consumption. Practically, the decrease of migration speed of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells observed under acid region was somewhat offset by addition of sodium pyruvate (Fig. 6b,d). In addition, inhibition of sodium-proton (Na+/H+) exchanger (NHE) function with cariporide improved migration speed (Fig. 6c,d), which was contradictory to the previous report27. Here, cariporide has been reported to downregulate cell adhesion35, and the fact is a possible reason for the increase of cell migration in the present study.

As limitations in this study, migration became active after 1 h (Fig. 5b), but after 3 h, cell adhesion became poor, resulting in detachment from the bottom of the media channel and the drifting of cells by slight convection. For longer time-lapse observations, the experimental method must be improved, such as periodic replacement and evaporation prevention of the cell culture medium and coating for cell adhesion. The presence or absence of ATRA in the cell culture medium may have affected the behavior of the differentiated cells when they were collected and introduced into the media channels. Furthermore, though this study focused on pH-dependent migration of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells, cellular experiments with multiple types of leukocytes would provide information on universality and specificity of pH responses depending on cell types. Future studies are expected to elucidate the pH-depending cell dynamics and their mechanisms for HL-60 cells of other phenotypes such as macrophage, as well as for other cell types like human monocytic leukemia cell line (THP-1) and natural immune cells by long-term observation and biochemical analysis at different pH levels and gradients.

Conclusion

We demonstrated the usefulness of the microfluidic device for studying cellular responses under pH-controlled microenvironments. Uniform pH conditions and a pH gradient from pH 8.3 to 6.8 were generated in the media channels by supplying gas mixtures at controlled CO2 concentration to the gas channels which manipulated the chemical equilibrium of NaHCO3. The migration of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells was then investigated, showing increase and suppression of migration speed in the high and low pH regions, respectively.

Methods

Chemical equilibrium utilizing sodium hydrogen carbonate

The pH of the cell culture medium was controlled by manipulating the chemical equilibrium of NaHCO3 in the cell culture medium by changing the dissolved CO2 concentration.

The equilibrium constants K1 and K2 of Eqs. (3) and (5) are given by Eq. (6) according to references17,36,37,38.

where T is the absolute temperature of the aqueous solution, and the values of (an, bn, cn) are (3404.71, 0.032786, 14.8435) and (2902.39, 0.02379, 6.4980) for n = 1 and 2, respectively. At 37 ℃ (T = 300 K), the constants are calculated as follows:

where the molar concentration of water was set to 1 ([H2O] = 1). The cell culture medium RPMI-1640 (183-02023, Wako, Japan) used in this study contained 0.0238 mol/L NaHCO3 (molar weight of 84). This leads to the following approximation with low CO2 concentration:

By calculating the molar concentration of hydrogen ions from Eqs. (7) - (9), the pH in the cell culture medium can be determined by Eq. (10):

where S is the solubility of CO2 in the cell culture medium, calculated as S = 25catm/100 [mM/atm] based on Henry’s law, considering the solubility of CO2 in water of 25 mM/atm at 37 ℃.

Microfluidic device

The previously developed microfluidic device with controllability of oxygen concentration was utilized for pH control (Fig. 1)20. The device was 30 mm square and 4 mm thick. It had three parallel media channels at 2-mm intervals on the bottom, and two parallel gas channels at 1-mm intervals perpendicular to the media channels at a height of 500 μm from the bottom. All channels were 2 mm wide and 150 µm high. The media channels were injected with a cell suspension of HL-60 cells, or cell culture medium mixed with uranine, depending on the experiments. The concentration of dissolved gases, i.e., CO2 in the present study, in the cell culture medium in the media channel was controlled by gas exchange through the PDMS between the media and gas channels by adjusting the components of gas mixtures supplied to the gas channels. The center position between the two gas channels was defined as the origin of the x-coordinate, and the directions parallel and perpendicular to the media channels were set as the x and y directions, respectively.

The device was fabricated by transferring the channel patterns onto PDMS (SILPOT, 184 W/C, Dow Toray, Japan) using soft lithography and bonding the PDMS to a glass coverslip after plasma treatment20,39. To reduce the effect of the ambient environment on the concentration of dissolved gases in the device, a polycarbonate film (0.5 mm thick) with low gas permeability was embedded at a height of 1 mm from the bottom of the device. In cellular experiments, the media channels were coated with 100 µg/mL of fibronectin (FC010, Merck Millipore, USA) diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (P5119, Sigma-Aldrich) for > 30 min to promote cell adhesion.

First, the pH controllability of the device was verified using a 1:1 mixture of RPMI-1640 with 10% heat-deactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (S1820, Biowest, France) (see Table 1) and bromothymol blue (BTB) solution. The mixture containing BTB was injected into the media channels, and then gas mixtures with 1% and 50% CO2 were supplied to the left and right gas channels, respectively. A color gradation from yellow to blue was observed, indicating that a pH gradient was generated in the media channels via gas exchange between the channels. For further quantification of the pH distribution, it was measured using the optical method described below.

Numerical simulation of CO2 concentration

The CO2 concentration in the microfluidic device was computed using COMSOL Multiphysics software (ver. 5.5, COMSOL AB, Sweden)20. The three-dimensional computational model of the microfluidic device was created based on computer aided design (CAD) data of the channel pattern. The Navier–Stokes equations and the equation of continuity were employed as the fundamental equations to analyze the flow field.

where u is the velocity vectors, p is the pressure, and ρ and μ are the density and viscosity of the fluid, respectively. The convection–diffusion equation was used to analyze the CO2 concentration c.

where D is the diffusion coefficient of CO2, and t is time. The physical parameters of each device material were set referring to references20,36,37,38,40,41,42,43 (Table 2). In the flow field analysis, the gas flow rate supplied to each gas channel was set to 30 mL/min, and the culture medium in the media channel was assumed to be static. For boundary conditions, flow velocity was determined at the inlet of the gas channels, zero pressure at the outlet, and no slip on the channel walls. For the analysis of CO2 concentration in the device, it was assumed that the device was placed in a 5% CO2 environment and that there was no flux through the bottom glass coverslip. The CO2 distribution in PDMS, PC, the cell culture medium, and at their interfaces with gas mixtures were set as mM units by the product of the solubility and concentration of CO2 in each material based on Henry’s law (see Table 2). At the interface between the PDMS and the cell culture medium, a partition condition of the mass flux of CO2 was applied to satisfy the continuity of the CO2 partial pressure:

where cPDMS and SPDMS are the concentration and solubility of CO2 in PDMS, respectively, and cmedium and Smedium are those in the cell culture medium (Table 2). The CO2 distribution in the device was computed for a uniform CO2 condition in which a gas mixture of 1, 5, 20, or 50% CO2 was supplied to both gas channels, and for a CO2 gradient condition in which gas mixtures of 1% and 50% CO2 were supplied to the left and right gas channels, respectively.

Measurement of pH distribution

The changes in pH of the cell culture medium with CO2 concentration were measured using an optical pH sensor (FireSting-PRO, PyroScience, Germany). For the experiment, 3 mL of cell culture medium (Table 1) in a 50-mL centrifuge tube was immersed in a thermostatic bath to maintain the temperature at 37 ± 0.5 °C. The medium was blown with gas mixtures of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 20, or 50% CO2 by a gas blender (MU-3400, HORIBA STEC, Japan, or 3MFC GAS MIXER, KOFLOK, Japan). Each gas mixture contained 21% O2 and N2 as the remaining gas component. The flow rate was set at 200, 100, 50, and 20 mL/min for the gas mixtures at ≤ 5, 10, 20, and 50% CO2, respectively, due to performance limitations of the gas blenders. The temperature and pH of the cell culture medium were measured every minute for 2 h. The pH measurement was performed three times for each CO2 concentration.

The pH distribution in the media channels was subsequently measured using uranine, which exhibits pH-dependent changes in fluorescence intensity. Uranine (F0096, Tokyo Chemical Industry, Japan) dissolved at 50 mM in pure water was further diluted with the cell culture medium to a final concentration of 50 µM, and then 50 µl of this medium was introduced into each media channel. The device was then placed in a stage incubator (STXG-WSKMX-SET, Tokai Hit, Japan) (37 °C) mounted on a fluorescence microscope (EVOS M7000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). A gas mixture at 5, 20, or 50% CO2 was supplied at 200 mL/min in total to both gas channels (30 mL/min each) and to the stage incubator (140 mL/min) to generate a uniform condition in the device at each CO2 concentration. A CO2 concentration gradient was generated in the device by supplying 1% and 50% CO2 gas mixtures to the left and right gas channels, respectively, while the stage incubator was filled with the 5% CO2 gas mixture. Each gas mixture contained 21% O2 and N2 as the remaining gas component (Table 3). Fluorescence microscopy images of the cell culture medium containing uranine were acquired 2 h after supply of the gas mixtures. The fluorescence intensity in each microscopic image was then quantified using the image analysis software ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, USA). A partial region of 5 mm × 0.1 mm set in the region of interest (ROI) at − 2.5 mm ≤ x ≤ 2.5 mm (see Fig. 1b). The ROI was further divided into 100 µm × 100 µm squares, and the spatial average of the fluorescence intensity, \(\overline{I }\), was measured in each area. Three devices were used in the validation experiment, and the pH distribution was evaluated with the nine media channels.

Cellular experiments under controlled pH

HL-60 cells, which are widely used as a model of leukocytes or neutrophils, were used for the cellular experiments under controlled pH conditions. We obtained the HL-60 cells from Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer Tohoku University. The cells were cultured in a 100-mm cell culture dish with the RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-deactivated FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (P/S; G6784, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) in an incubator (5% CO2, 37 °C) (Table 1). The cells were kept at a cell density between 1 × 105 and 1 × 106 cells/mL, and those between the 6th and 15th passages were used in the experiments. To induce the differentiation of HL-60 cells into neutrophil-like cells, the cells were cultured with the RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-deactivated FBS and 1 µM all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA; 186-01114, Wako, Japan) for 5 days, keeping the cell density at 2 × 105 cells/mL (Table 1)44. The differentiation of HL-60 cells into neutrophil-like phenotype was confirmed by the nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction test using phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA). The cell suspension was supplemented with 1 mg/mL of NBT (N6876, Sigma-Aldrich) and 1 µg/mL of PMA (10008014, Cayman Chemical, USA), and incubated for 15 min. After washing with PBS, the number of differentiated and non-differentiated cells was counted, and > 40% of the cells were differentiated (Fig. S3). Subsequently, 50 µL of neutrophil-like HL-60 cell suspension (3 × 106 cells/mL) was injected into each of the media channels in the microfluidic device. After a 30-min incubation, cells that did not adhere to the media channels were washed out by exchanging the medium with fresh cell culture medium (Table 1). Here, for further investigation of the mechanisms for variation of migration speed with pH, chemical materials were individually supplemented to the cell culture medium for cellular experiments. In case of inducing chemical stimulus by a complement, 10 nM fMLP (063-02811, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical, Japan) was added45,46. A 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360070, Thermo Fisher Scientific) or 10 µM cariporide (SML1360, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to examine effects by energy consumption for pH-homeostasis and by NHE function27,47,48. The device was then placed in a stage incubator (INUBSF-ZILCS, Tokai Hit) (5% CO2, 37 °C) mounted on a disk scanning microscope (IX83-DSU, Olympus, Japan) or a fluorescence microscope (EVOS M7000, Thermo Fisher Scientific). By supplying gas mixtures to the gas channels as summarized in Table 3, a uniform CO2 concentration or a CO2 concentration gradient (uniform pH or pH gradient) was generated in the media channels. The flow rate of the gas mixture supplied to each gas channel was set at > 30 mL/min. Immediately after supply of the gas mixtures was initiated, time-lapse observations of the cells in the media channels were started. Phase-contrast microscopy images were collected every minute for 3 h, covering the 5 mm × 1 mm ROI (see Fig. 1b) with the tiling function. Three devices were used for the experiments in each condition.

The migration of HL-60 cells in sequential microscopic images was measured by particle tracking velocimetry. Cell positions were determined by analyzing microscopic images using Find Maxima, a built-in plugin of the image analysis software ImageJ. Subsequently, cell trajectories were determined by a squared-displacement minimization algorithm coded with MATLAB (MathWorks, USA)49. The displacement per minute (velocity) and its absolute value (speed) were calculated, and the average values were obtained in each subregion of the ROI divided every 200 µm in the x-direction. Moreover, in the subdivided regions A1-A5 of the ROI divided every 1 mm in the x-direction (see Fig. 1b), the persistency of migration was evaluated by calculating the ratio of the total length of the cell migration trajectory to the distance between the initial and final points. Approximately 2000 cells (mean ± S.D. = 2274 ± 649) were measured in each media channel. Significant differences in each metric were assessed by the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test or the two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons, and statistical significance was inferred at P < 0.05.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Almezhghwi, K. & Serte, S. Improved classification of white blood cells with the generative adversarial network and deep convolutional neural network. Comput. Intel. Neurosc. 2020, 6490479 (2020).

Kolaczkowska, E. & Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 159–175 (2013).

Zeidler, C., Germeshausen, M., Klein, C. & Welte, K. Clinical implications of ELA2-, HAX1-, and G-CSF-receptor (CSF3R) mutations in severe congenital neutropenia. Br. J. Haematol. 144, 459–467 (2009).

Petri, B. & Sanz, M. J. Neutrophil chemotaxis. Cell Tissue Res. 371, 425–436 (2018).

Millius, A. & Weiner, O. D. Manipulation of neutrophil-like HL-60 cells for the study of directed cell migration. Methods Mol. Biol. 591, 147–158 (2010).

Rosales, C. Neutrophil: A cell with many roles in inflammation or several cell types?. Front. Physiol. 9, 113 (2018).

Mantovani, A., Cassatella, M. A., Costantini, C. & Jaillon, S. Neutrophils in the activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11, 519–531 (2011).

Gaohua, L., Miao, X. & Dou, L. Crosstalk of physiological pH and chemical pKa under the umbrella of physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 17, 1103–1124 (2021).

Aoi, W. & Marunaka, Y. Importance of pH homeostasis in metabolic health and diseases: Crucial role of membrane proton transport. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 598986 (2014).

Erra Diaz, F., Dantas, E. & Geffner, J. Unravelling the interplay between extracellular acidosis and immune cells. Mediators Inflamm. 2018, 1218297 (2018).

Kruse, C. R. et al. The effect of pH on cell viability, cell migration, cell proliferation, wound closure, and wound reepithelialization: In vitro and in vivo study. Wound Repair Regen. 25, 260–269 (2017).

Gillies, R. J., Raghunand, N., Garcia-Martin, M. L. & Gatenby, R. A. PH imaging. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. 23, 57–64 (2004).

Emmett, M. Metabolic alkalosis: A brief pathophysiologic review. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 15, 1848–1856 (2020).

Palmer, B. F. & Clegg, D. J. Respiratory acidosis and respiratory alkalosis: Core curriculum 2023. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 82, 347–359 (2023).

Behnen, M., Möller, S., Brozek, A., Klinger, M. & Laskay, T. Extracellular acidification inhibits the ROS-dependent formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Front. Immunol. 8, 184 (2017).

Garcia, A. J. & Ramirez, J. M. Chemoreception: Keeping carbon dioxide in check. Elife 6, e27563 (2017).

Saruhashi, K. On the equilibrium concentration ratio of carbonic acid substances dissolved in natural water: A study on the metabolism in natural waters (II). Pap. Meteorol. Geophys. 6, 38–55 (1955).

Mackenzie, C., Mackenzie, J. B. & Beck, P. Effect of pH on growth, protein synthesis, and lipid-rich particles of cultured mammalian cells. J. Biophys. Biochem. Cytol. 9, 141–156 (1961).

Funamoto, K. et al. A novel microfluidic platform for high-resolution imaging of a three-dimensional cell culture under a controlled hypoxic environment. Lab Chip 12, 4855–4863 (2012).

Hirose, S., Rieu, J. P., Cochet-Escartin, O., Anjard, C. & Funamoto, K. The oxygen gradient in hypoxic conditions enhances and guides migration. Processes 10, 318 (2022).

Koens, R. et al. Microfluidic platform for three-dimensional cell culture under spatiotemporal heterogeneity of oxygen tension. APL Bioeng. 4, 016106 (2020).

Zhuang, J., Wright Carlsen, R. & Sitti, M. pH-taxis of biohybrid microsystems. Sci. Rep. 5, 11403 (2015).

Kuriyama, R., Tanaka, Y., Akiyama, S. & Sato, Y. Precise near-wall pH measurement in pressure-driven and electrically-driven flows using nanoscale laser-induced fluorescence imaging. Meas. Sci. Technol. 30, 115204 (2019).

Jagielska, A., Wilhite, K. D. & Van Vliet, K. J. Extracellular acidic pH inhibits oligodendrocyte precursor viability, migration, and differentiation. Plos One 8, e76048 (2013).

Paradise, R. K., Whitfield, M. J., Lauffenburger, D. A. & Van Vliet, K. J. Directional cell migration in an extracellular pH gradient: A model study with an engineered cell line and primary microvascular endothelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 319, 487–497 (2013).

Takahashi, E., Yamaguchi, D. & Yamaoka, Y. A relatively small gradient of extracellular pH directs migration of MDA-MB-231 cells in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (2020).

Oster, L. et al. Extracellular pH controls chemotaxis of neutrophil granulocytes by regulating leukotriene B production and Cdc42 signaling. J. Immunol. 209, 136–144 (2022).

Khachaturyan, G. et al. Temperature-sensitive migration dynamics in neutrophil-differentiated HL-60 cells. Sci. Rep. 12, 7053 (2022).

Hauert, A. B., Martinelli, S., Marone, C. & Niggli, V. Differentiated HL-60 cells are a valid model system for the analysis of human neutrophil migration and chemotaxis. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34, 838–854 (2002).

Manda-Handzlik, A. et al. The influence of agents differentiating HL-60 cells toward granulocyte-like cells on their ability to release neutrophil extracellular traps. Immunol. Cell Biol. 96, 413–425 (2018).

Hou, W., Wang, Z.-Y., Lin, J. & Chen, W.-M. Induction of differentiation of the acute myeloid leukemia cell line (HL-60) by a securinine dimer. Cell Death Discov. 6, 123 (2020).

Rotstein, O. D., Fiegel, V. D., Simmons, R. L. & Knighton, D. R. The deleterious effect of reduced pH and hypoxia on neutrophil migration in vitro. J. Surg. Res. 45, 298–303 (1988).

Shi, Y., Kim, D., Caldwell, M. & Sun, D. The role of Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1 in inflammatory responses: Maintaining H+ homeostasis of immune cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 961, 411–418 (2013).

Doyen, D., et al. Intracellular pH control by membrane transport in mammalian cells. Insights into the selective advantages of functional redundancy. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 825028 (2022).

Kaba, N. K., Schultz, J., Law, F.-Y., Lefort, C. T., Martel-Gallegos, G., Kim, M., Waugh, R. E., Arreola, J. & Philip A. Knauf. Inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger enhances low pH-induced L-selectin shedding and β2-integrin surface expression in human neutrophils. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 295, C1454–C1463 (2008).

Harned, H. S. & Davis, R. The ionization constant of carbonic acid in water and the solubility of carbon dioxide in water and aqueous salt solutions from 0 to 50°. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 65, 2030–2037 (1943).

Harned, H. S. & Scholes, S. R. Jr. The ionization constant of HCO3- from 0 to 50°. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 63, 1706–1709 (1941).

Versteeg, G. F. & Vanswaaij, W. P. M. Solubility and diffusivity of acid gases (CO2, N2O) in aqueous alkanolamine solutions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 33, 29–34 (1988).

Tomita, M., Hirose, S. & Funamoto, K. Proc. 16th IEEE Int. Conf. Nano/Molecular Med. Eng. 179–182 (2023).

Allaire, S. A. & van Bochove, E. Collecting large soil monoliths. Can. J. Soil Sci. 86, 885–896 (2006).

Charati, S. G. & Stern, S. A. Diffusion of gases in silicone polymers: Molecular dynamics simulations. Macromolecules 31, 5529–5535 (1998).

Frank, M. J. W., Kuipers, J. A. M. & vanSwaaij, W. P. M. Diffusion coefficients and viscosities of CO2+H2O, CO2+CH3OH, NH3+H2O, and NH3+CH3OH liquid mixtures. J. Chem. Eng. Data 41, 297–302 (1996).

Merkel, T. C., Bondar, V. I., Nagai, K., Freeman, B. D. & Pinnau, I. Gas sorption, diffusion, and permeation in poly(dimethylsiloxane). J. Polym. Sci. Pol. Phys. 38, 415–434 (2000).

Breitman, T. R., Selonick, S. E. & Collins, S. J. Induction of differentiation of the human promyelocytic leukemia cell line (HL-60) by retinoic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77, 2936–2940 (1980).

Carrigan, S. O., Weppler, A. L., Issekutz, A. C. & Stadnyk, A. W. Neutrophil differentiated HL-60 cells model Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18)-independent neutrophil transepithelial migration. Immunology 115, 108–117 (2005).

Lehman, N. et al. Phagocyte cell migration is mediated by phospholipases PLD1 and PLD2. Blood 108, 3564–3572 (2006).

Mazan, A. & Marusiak, A. A. Protocols for co-culture phenotypic assays with breast cancer cells and THP-1-derived macrophages. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 29, 4 (2024).

Masereel, B., Pochet, L. & Laeckmann, D. An overview of inhibitors of Na+/H+ exchanger. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 38, 547–554 (2003).

Blair, D. & Dufresne, E. The Matlab Particle Tracking Code Repository. https://site.physics.georgetown.edu/matlab/ (accessed on January 24, 2024).

Acknowledgements

K.F. acknowledges funding from JST PRESTO (Grant No. JPMJPR22O8) and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. 22K19887).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.F. conceived the idea for the study. M.T., S.H., and K.F. performed theoretical analysis and numerical simulation regarding pH control in the device. M.T. conducted pH measurements and validation experiments of the microfluidic device. M.T., S.H., and T.N. performed cellular experiments and analyzed the data. M.T., S.H., T.N., and K.F. interpreted and validated the data. K.F. obtained funding support and supervised the study. M.T. and K.F. drafted the manuscript, and M.T., S.H., and K.F. edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomita, M., Hirose, S., Nakamura, T. et al. pH-Dependent migratory behaviors of neutrophil-like cells in a microfluidic device with controllability of dissolved gas concentrations. Sci Rep 14, 28730 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79625-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79625-3