Abstract

Bioaerosol studies showed that wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are a significant source of bioaerosol emissions. In this study, 170 samples of total bacteria, total coliform, and total fungi were collected from 10 sites within a domestic WWTP, Alexandria, Egypt, using the sedimentation technique. According to the Index of Microbial Air Contamination (IMA) classes, the total bacteria range was 108–5120 CFU/dm2/hour, and all samples were classified as “very poor” except one sample of an office, which was classified as “poor.” The total coliform range was 0–565 CFU/dm2/hour, and 6 samples were classified as “very poor,” while one sample was classified as “poor.” The total fungi range was 0–209 CFU/dm2/hour, and 9 samples were classified as “very poor,” while 4 samples were classified as “poor.” After the conversion to CFU/m3, the counts of total bacteria, total coliforms, and total fungi were 897 − 42.7 × 103, 0–4.71 × 103, and 0–2.69 × 103 CFU/m3, respectively. Several identified bioaerosols have been reported before as a cause of human infections. They included Lysinibacillus fusiformis, Bacillus cereus, Alcaligenes faecalis, Klebsiella sp., Escherichia coli, Aspergillus spp., Penicillium spp., Rhizopus sp., Candida sp., and Rhodotorula sp. These results indicated an increased health risk to WWTP staff, which needs more attention and more efficient control measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution alone causes about 7 million deaths a year, ranking it among the top global risks to health1. Air pollutants can be classified as non-biological particles, biological particles, gases, and physical pollutants2,3. Any airborne particles derived from biological sources, such as bacteria, viruses, fungus, plants, animals, and protozoa, are referred to as bioaerosols4. Even though bioaerosols represent a small fraction of all aerosol particles in our surroundings, their effects can be crucial as a single viable microbial pathogen could be sufficient to spread infection5. It’s a multidisciplinary study area that comprises fields such as microbiology, mechanical engineering, air pollution, medical science, epidemiology, immunological science, biochemistry, nanotechnologies, etc6. A significant knowledge gap still exists till now in the scientific understanding of the physical characteristics and monitoring of bioaerosols, and more studies are needed covering developing countries7,8.

Human exposure to bioaerosols has been correlated with a range of acute and chronic adverse health effects and diseases that are related to toxic and allergenic materials, and to infectious diseases from pathogenic biological agents. Respiratory infections (e.g. rhinitis, asthma, bronchitis and sinusitis), which often can be linked to inhaled pathogens, are the most severe diseases worldwide in terms of mortality. Other health problems reported include digestive disorders, fatigue, weakness and headache5,9. Recently, COVID-19 (as a type of bioaerosols) caused 7,043,660 deaths worldwide till 31 March 202410.

The number of methods available for the collection of microorganisms is roughly equal to the number of investigators11. These numerous methods included conventional methods and real-time samplers. On the other hand, the absence of an accurate, rapid, easy, and inexpensive method for quantifying bioaerosols remains a barrier in the bioaerosols assessment. Therfore, choosing the appropriate method for bioaerosols monitoring remains a challenge8. Sedimentation is one of the commonly used methods in which microorganisms settle directly on the agar medium under the influence of gravity12,13. Cartwright et al.14 stated that sedimentation cannot used for quantitative monitoring as the volume of sampled air is not determined. Likewise, Michalkiewicz15 and Viani et al.16 reported that this technique give an overestimation of the risk. Contrariwise, its reliability was examined by comparing fungi counts collected by sedimentation, impingement, and filtration methods17. Furthermore, Manibusan & Mainelis18 suggested that using of this technique alongside active collection devices can assist researchers in developing countries for comprehensive understanding of biological presence and dynamics. Several studies have applied sedimentation technique for quantitative bioaerosols monitoring in different environments13,19,20,21,22,23. In addition, Korzeniewska et al.24, Gotkowska-Plachta et al.25, and Aborawash et al.26 used this technique for sampling and quantifying bioaerosols from wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). For identification of bioaerosols; despite the fact that morphological characters for bacteria identification are few and limiting27, identification based on morphology is a primary step for classifying fungal pathogens at the genus level28. In few decades, identifying bacterial isolates in the clinical laboratory by proteomics and sequence rather than phenotype has dramatically improved the diagnostic and epidemiological capabilities of clinical microbiology laboratories29.

Extensive review of bioaerosols studies revealed that WWTPs represent a significant source of bioaerosols emissions and workers of WWTPs are exposed to these bioaerosols through various pathways such as ingestion, skin or mucosal contact, inhalation, and contact with contaminated surfaces, clothes or tools etc. WWTPs associated bioaerosols have emerged as one of the critical sustainability indicators, ensuring health and well-being of societies and cities30. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to quantify and identify total bacteria, and total fungi in the air of a domestic WWTP and describe their characteristics. Also, total coliform was measured as it reflects the level of air pollution with bioaerosols from sewage around WWTPs15.

Materials and methods

Sampling sites

Alexandria Governorate has 20 WWTPs31, and this study aims to assess the risks of bioaerosols emitted from the biggest WWTP in Alexandria (Eastern Wastewater Treatment Plant). This WWTP has a capacity of 800,000 m3/day (1,040,000 m3/day as peak flow). The process consists of pretreatment and primary treatment (5 screens followed by 10 grit and grease removal chambers then 16 primary clarifiers), 12 modules for biological treatment (1 aeration tank + 2 clarifiers for each module), sludge treatment (thickening and dewatering), and chlorination unit32. Total bacteria (total culturable mesophilic bacteria), total coliform, and total fungi (total culturable fungi) were monitored in 10 sites within the WWTP (Fig. 1); grit removal and screens (outdoor, 1st floor between screens and grit removal chambers), primary clarifiers (outdoor, on the edge of the tank), final clarifiers (outdoor, on the upper way between tanks), aeration tanks (outdoor, on the upper way between tanks), sludge treatment (indoor, 1st floor and ground floor), upwind (outdoor), downwind (outdoor), and 2 offices (indoor).

Samples preparation

Samples were collected on 90 mm Petri dishes containing different types of media, nutrient agar (NA) (HIMedia, India) for total bacteria (28 g was dissolved in 1 L of distilled water and then sterilized by autoclaving at 15 lbs pressure “121 °C” for 15 min), M-Endo agar (HIMedia, India) for total cform (25.5 g was dissolved in 490 ml of distilled water and heated to boiling without autoclaving, then 10 ml of ethanol 95% are added), and sabouraud 4% dextrose agar (SDA) (Merck, Germany) for total fungi (32.5 g was dissolved in 500 g of distilled water, 50 mg of Chloramphenicol (NEOGEN, USA) was added to inhibit bacterial growth, then sterilized by autoclaving at 15 lbs pressure “121 °C” for 15 min).

Field sampling

Total bacteria, total coliform, and total fungi were sampled 5–6 times in 10 sites (170 samples as a total) during November and December 2021 using the sedimentation technique during day working hours (mainly between 9:00 am and 02:00 pm). The average sampling time was 10 min, and the samples were taken at the height of 100: 145 cm (close to/within the breathing zone for standing workers) in 8 sites, while samples in offices were taken at the height of 75 cm (within the breathing zone for seated workers). Samples were transported between the sampling site and the lab in an icebox, and the transportation time didn not exceed 40 min for any trip. Meteorological data was available online from Alexandria station (HEAX) which is located about 2 km from the WWTP. During the 6 sampling campaigns, temperature range was (16.7–27.15 °C), relative humidity range was (53.67–77.25%), wind speed range was (1.6–3.6 m/s), and precipitation was (0 mm).

Laboratory analysis

Total bacteria and total coliform were incubated for about 48 h (at 36 ± 1 °C) and grown colonies (Fig. 2-a and b) were enumerated using a manual colony counter after 24 and 48 h, while total fungi were incubated for 5 days (at 28 ± 1 °C) and colonies were enumerated every day as some colonies may cover the whole plate after the 5 days (Fig. 2-c). Results were expressed as CFU/dm2/hour and then compared to the index of microbial air contamination classes (IMA class) as 0–9 CFU/dm2/h (very good), 10–39 CFU/dm2/h (good), 40–84 CFU/dm2/h (fair), 85–124 CFU/dm2/h (poor), and ≥ 125 CFU/dm2/h (very poor)33,34.

In addition, results were expressed as CFU/m3 using omeliansky’s formula: N = 5 a × 104 (bt)−1 where, N is the count in CFU/m3, a is th number of colonies per Petri dish, b is the Petri dish area in cm2, t is the exposure time in minutes35. There is no uniform international standard available up till now for acceptable counts of bioaerosol36,37. Table 1 shows suggested limits that were used to compare the study results.

Isolated bacterial colonies were identified using 16 S rRNA gene sequencing. Firstly, the total DNA of isolated bacterial colonies was extracted from samples using Quick-DNA™ Fungal/Bacterial Microprep Kit (Zymo Research, USA). 50–100 mg (wet weight) bacterial cells have been re-suspended in up to 200 µl of water and added to a ZR BashingBead™ Lysis Tube (0.1 mm & 0.5 mm). 750 µl BashingBead™ Buffer was added to the tube. The tube was secured in a bead beater fitted with a 2 ml tube holder assembly and processed at maximum speed for ≥ 5 min then it was centrifuged in a microcentrifuge at 10,000 x g for 1 min. 400 µl of the supernatant was transferred to a Zymo-Spin™ III-F Filter in a Collection Tube and centrifuged at 8000 x g for 1 min. 1200 µl of Genomic Lysis Buffer was added to the filtrate in the Collection Tube then 800 µl of the mixture transferred to a Zymo-Spin™ IICR Column3 in a Collection Tube and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. The flow through from the Collection Tube was discarded and the previous step was repeated. Add 200 µl DNA Pre-Wash Buffer was added to the Zymo-Spin™ IICR Column in a new Collection Tube and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. 500 µl g-DNA Wash Buffer was added to the Zymo-Spin™ IICR Column and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 1 min. Finally, the Zymo-Spin™ IICR Column was transferred to a clean 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube and 100 µl DNA Elution Buffer was added directly to the column matrix and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 s to elute the DNA. Then, The PCR amplification reaction was performed using COSMO PCR RED Master Mix (willowfort, UK). 25 µl of COSMO PCR RED Master Mix and 1–2.5 µl of Forward and Reverse Primers (20µM) were mixed in a nuclease free Eppendorf. Nuclease-free water was added to 50 µl. The master mix was aliquoted into separate 0.2mL PCR tubes before adding the DNA template. The components were mixed gently and centrifuged briefly. The PCR reaction program was set under the following PCR conditions: 95 °C for 2 min “for stage 1”, Primer Tm < 5 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 30–60 s “for stage 2 and repeated 25–35 cycles”, then 72 °C for 1 min “stage 3”.

Finally, the forward and reverse sequences were refined and merged using BioEdit, version 7.2.544, and the identity of bacterial isolates was assigned by comparing their DNA sequences with those available in the GenBank NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database using a BLAST+45, version: 2.13.0 using the following settings: Models (XM/XP) and (Uncultured/environmental sample sequences) were excluded, Megablast (Results were optimized for highly similar sequences), and results with unspecified species were excluded. Phylogenetic and molecular evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA version 1146. Coliform and fungi colonies were identified only to the genus level according to the macroscopic morphological characteristics.

Results and discussion

Enumeration of bioaerosols

According to IMA classes, total bacteria ranged from 108 to 5,120 CFU/dm2/hour and all samples were classified as “very poor” (≥ 125 CFU/dm2/hour) (except an office on the 1st day of sampling which was classified as “poor”). Total coliform ranged from 0 to 565 CFU/dm2/hour and 6 samples were classified as “very poor” while one sample was classified as “poor”. Total fungi ranged from 0 to 209 CFU/dm2/hour and 9 samples were classified as “very poor” while 4 samples were classified as “poor”.

After the conversion of CFU/plate to CFU/m3 using omeliansky’s formula, the count of total bacteria, total coliform, and total fungi varied as shown in Table 2; Fig. 3a-c. Twenty eight samples recorded counts of total bacteria higher than all suggested thresholds (> 104 CFU/m3) and Grit removal & screens phase and primary clarifiers recorded the highest mean, while one of the administration offices recorded the lowest mean. For total coliform, the primary clarifiers and grit removal phase & screens recorded the highest mean, while other sites recorded limited contamination with coliform. For total fungi, 8 of 59 samples recorded levels higher than all suggested thresholds (> 1,000 CFU/m3), and samples of primary clarifiers recorded the highest mean, while the ground floor of the mechanical dewatering building (sludge treatment) recorded the lowest mean.

Box plot for (a) total bacteria counts, (b) total coliform counts, and (c) total fungi counts per each sampling site (vertical boxes representing approximately 50% of the observations, whiskers extending from the box roughly represent the upper and lower 25% of the distribution, median values indicated by the horizontal line inside the box, and a circle-cross symbols represent the means).

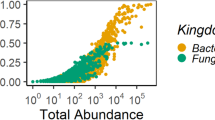

For comparison, the findings of this work revealed that total bacteria count ranged between 897 and 4.27 × 104 CFU/m3. Total bacteria count ranges varied widely in the previous studies (Fig. 4-a). Michałkiewicz47 described that total bacteria count from 11 Municipal WWTPs in Poland was within range from 0 to 1.95 × 105 CFU/m3. Conversely, Han et al.48 displayed total bacteria count generated in the air from sludge dewatering houses of 9 WWTP in China ranged only between 132 ± 7 and 1.53 × 103 ± 155 CFU/m3.

This wide variation might be because of heterogeneity among sampling methods and WWTPs features such as:

-

(a)

Number of sampling points within WWTPs: Heinonen-Tanski et al.52, Han et al.48, and Haas et al.53 reported their results only from one sampling site within the WWTPs (Total bacteria ranges: 400 –1.76 × 105, 132 ± 7–1.53 × 103 ± 155, and 4–1.1 × 104 CFU/m3, respectively. On the contrary; Dehghani et al.59 sampled total bacteria and total fungi in 25 sites within the WWTP and reported a range from 21 ± 3 to 2.58 × 103 ± 401. In this study, 10 sites were selected to represent all stages.

-

(b)

Sampling instruments: In this study, the sedimentation method was used for bioaerosols sampling, while Gotkowska-Plachta et al.25 used sedimentation and impaction methods and recorded a range of 1.2–8.0 × 104 CFU/m3. Heinonen-Tanski et al.52 used a bio-sampler liquid impinger and recorded 0.4 × 103 − 1.76 × 105 CFU/m3. Furthermore, Han et al.48 collected samples on a quartz microfiber filter via a suction pump and reported a range from 132 ± 7 to 1.53 × 103 ± 155 CFU/m3. Others depended on Six-stage Andersen impactors or Single-stage impactors and reported various ranges.

-

(c)

Sampling duration: Sánchez-Monedero et al.51 reported their results for 3 replicates per each sampling site (22–4.58 × 103 CFU/m3). Kowalski et al.58 conducted a sampling campaign for only one day (0–6.9 × 103 CFU/m3). In this study, sampling campaigns were conducted during November and December. On the other hand, Gotkowska-Plachta et al.25 collected samples for two annual cycles in spring, summer, autumn, and winter (1.2–8.0 × 104 CFU/m3).

-

(d)

Incubation conditions: A big variation in incubation temperatures and time was noticed. In this study, bacteria were incubated at ≈ 37 °C for 48 h as followed in several studies. Contrariwise, Ding et al.56 and Han et al.48 incubated bacteria at 30 °C for 48 h (1.48 × 103 ± 434 − 4.16 × 103 ± 550, 132 ± 71–1.53 × 103 ± 155 CFU/m3, respectively), Oppliger et al.50 incubated bacteria also at 30 °C but for 7 days (2.62–75.0 × 104 CFU/m3). Furthermore, Gotkowska-Plachta et al.25 incubated bacteria at 26 °C for 72 h (1.2–8.0 × 104 CFU/m3). In addition, total bacteria were incubated at 20 °C for 3–4 days53, and for 7–8 days49, and various ranges were reported (ND − 6.9 × 103, 0.4 × 103–1.76 × 105 CFU/m3, respectively).

-

(e)

Distance from the source: Kowalski et al.58 captured total bacteria close to the wastewater effluent (ND – 6.9 × 103 CFU/m3). As well as in this study. Gotkowska-Plachta et al.25 took all samples downwind (approximately 1 to 1.5 m from the source) and reported a range from 1.2 to 8.0 × 104 CFU/m3. Furthermore, Sánchez-Monedero et al.51 conducted outdoor sampling 2–10 m downwind of the operations (22–4.58 × 103 CFU/m3).

-

(f)

Capacity of WWTPs: In this study, the WWTP normal capacity is 800,000 m3/day (1,040,000 m3/day as peak flow)32, while Michałkiewicz47 sampled bioaerosols from 11 WWTPs with capacities ranging from 350 to 200,000 m3/day and reported a range of 0–1.95 × 105 CFU/m3. On the contrary, Ding et al.56 performed their study in a WWTP with a capacity of 100 m3/day only and the range was from 1.48 × 103 ± 434 to 4.16 × 103 ± 550 CFU/m3.

-

(g)

Design of WWTPs: WWTPs varied widely in design; (1) Operations may be outdoor or indoor, uncovered or shaded or partially shaded, (2) Indoor phases may be equipped with ventilation system or not, (3) sedimentation tanks and aeration tanks may be constructed above or under the ground level, etc. In this study, the grit removal phase was partially shaded, while primary clarifiers, aeration tanks, and final clarifiers were constructed outdoors without shading.

For the total coliform, the findings of this study revealed that the count ranged from 0 to 4.7 × 103 CFU/m3. These results were consistent with the study of Pascual et al.49 who reported that the count of total coliform in a municipal WWTP in Spain was within a range of 0 and 3.1 × 102 CFU/m3. In the same study49, the pretreatment phase recorded the highest count of total coliform (35–3190 CFU/m3 with a median of 205 CFU/m3) followed by primary clarifiers (20–1165 CFU/m3 with a median of 149 CFU/m3). In addition, Haas et al.53 described that total coliform count generated from three WWTPs in Austria was within a range of 0 and 4.4 × 102 CFU/m3. Furthermore, Katsivela et al.57 reported a very low count of total coliform in the grit removal phase only (29 ± 27 CFU/m3) and Michałkiewicz47 displayed that total coliform count generated from 11 municipal WWTP in Poland ranged between 0 and 8.8 × 104 CFU/m3.

For the total fungi, the findings of this work revealed that the count ranged between 0 and 2.69 × 103 CFU/m3. Total fungi count ranges varied widely in the previous studies (Fig. 4-b). Vítězová et al.54 described that total fungi count generated from WWTPs in Czech were within a range of 25 and 3.2 × 104 CFU/m3. Conversely, Katsivela et al.57 displayed total fungi count generated in a WWTP in Greece ranged only between 70 and 204 CFU/m3. This variation might be attributed to the same variables mentioned above.

Identification of bioaerosols

Identification of isolated bacteria

Twenty bacterial colonies were isolated from collected samples within the domestic WWTP. The 16 S rDNA sequences of the dominant 9 bacterial colonies (B2, B6, B8, B9, B12, B13, B14, B15, and B17) were extracted partially and compared with those available in the GenBank NCBI database using a BLAST+. These isolates identified as Brevibacterium linens (B02), Citricoccus zhacaiensis (B06), Bacillus sp. (B08), Lysinibacillus fusiformis (B09), Bacillus sp. (B12), Bacillus cereus (B13), Planococcus rifietoensis (B14), Alcaligenes faecalis (B15), and Bacillus safensis (B17) as shown in Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic trees of the dominant bacterial isolates at the eastern WWTP (Alexandria, Egypt), (a) Brevibacterium linens strain B01 (PQ164272), (b) Citricoccus zhacaiensis strain B06 (PQ164273), (c) Bacillus sp. strain B08 (PQ164282), (d) Lysinibacillus fusiformis strain B09 (PQ164283), (e) Bacillus sp. strain B12 (PQ164289), (f) Bacillus cereus strain B13 (PQ164339), (g) Planococcus rifietoensis strain B14 (PQ164341), (h) Alcaligenes faecalis strain B15 (164346), and (i) Bacillus safensis strain B17 (PQ164347).

The phylogenetic tree of Brevibacterium linens (B02) showed a strong similarity with B. epidermidis which was isolated formerly from nitrocellulose-contaminated wastewater environments62. The phylogenetic tree of B06 (Citricoccus zhacaiensis) showed a strong similarity with Micrococcus xinjiangensis. Micrococcus sp. was also isolated previously from WWTPs60,63. The phylogenetic trees of strains B08 and B12 showed similarity with several species of the Bacillus genus. Several Bacillus spp. were isolated previously from the air of WWTPs63,64. B09 (L. fusiformis) is recognized as a ubiquitous environmental bacterium and has been isolated from wastewater, plants, and soil. Also, L. fusiformis is believed to cause tropical ulcers65. Bacillus cereus (B13) was isolated previously from the air of a WWTP66. B. cereus is well known as a cause of food poisoning and much more is now known about the toxins produced by various strains of this species67. B14 was identified as Planococcus rifietoensis which was reported as a carotenoid pigment producer and as a bio-remediator of paper pulp mill effluent, in an economically and industrially important way68. Alcaligenes faecalis (B15) usually causes opportunistic infections in humans. Its infection is often difficult to treat due to its increased resistance to several antibiotics. The most frequent A. faecalis infection sites, in order, are the bloodstream, urinary tract, skin and soft tissue, and middle ear69.

These results confirmed that there is a high degree of a complete similarity across the length of 16 S rRNA for many microorganism groups that don’t allow identification to the species level for some or all species within certain genera29. This limitation of 16 S rRNA sequencing was reported early by Fox et al.70 by comparing 16 S rRNA sequences for Bacillus globisporus W25T (T = type strain) and Bacillus psychrophilus W16AT, and W5. These strains exhibited more than 99.5% sequence identity and within experimental uncertainty could be regarded as identical. Consequently, 16 S rRNA gene identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity.

Identification of isolated coliform

According to morphological characteristics of coliform colonies stated in the technical data of M-endo agar (HiMedia Laboratories, India), Escherichia coli was abundant in all samples (pink colonies with metallic sheen), Klebsiella sp. appeared in a few numbers in some samples (pink to red colonies), and no Salmonella sp. colonies were observed (colorless to very light pink colonies). Both E. coli and Klebsiella sp. were isolated previously from the air of WWTP24,71,72,73. E. coli is the most common pathogen leading to uncomplicated cystitis, and causes other extra-intestinal illnesses, including pneumonia, bacteremia, and abdominal infections such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis74. Besides, Klebsiella represent a severe pathogen that cause pneumonia, bacteremia, thrombophlebitis, urinary tract infection, cholecystitis, diarrhea, upper respiratory tract infection, wound infection, osteomyelitis, and meningitis75.

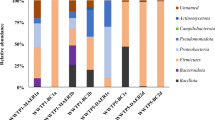

Identification of isolated fungi

According to morphological characteristics, 9 of the 29 isolated fungi colonies (Fig. 6) were identified (only to the genus level)76,77,78,79,80, while other isolated fungi colonies require further studies to be identified. Identified colonies were Aspergillus spp. (F01, F02, and F03), Penicillium spp. (F04, F05, and F06), Rhizopus sp. (F07), Candida sp. (F08), and Rhodotorula sp. (F09). All the identified fungal genera were isolated previously from the air of WWTPs; Penicillium spp. and Aspergillus spp51,63,81,82,83,84. , Rhizopus sp. and Rhodotorula sp63,85. , and Candida sp83,85. Unfortunately, several species of these genera were classified as pathogenic fungi86.

Conclusion

To decrease the gap in the scientific understanding of the overall physical characteristics and measurement of bioaerosols, especially in developing countries, total bacteria, total coliform, and total fungi in the air of a WWTP were monitored by sedimentation method and identified by using 16 S rRNA gene sequencing (for total bacterial isolates), and morphological characteristics (for total coliform and total fungi). The study revealed the following conclusions:

-

1.

High counts were recorded for total bacteria and total fungi in most samples for all sites. The primary clarifiers and grit removal phase recorded the highest mean of total coliform count while other sites recorded limited contamination with coliform. Several bioaerosols, that have been reported before as a cause of human infections, were identified.

-

2.

The absence of an international standard for acceptable limits for pathogenic bioaerosols as all suggested limits related to total bacteria and total fungi which includes several non-pathogenic species.

-

3.

The 16 S rRNA gene sequencing may not be sufficient to guarantee species and strain identity. Morphological tests, biochemical tests, or sequencing of other genes may be needed in parallel with partial 16 S rRNA sequencing for accurate identification of bacterial isolates.

Looking forward to the future, further studies of monitoring bioaerosols are needed to investigate the diversity of bioaerosols by expanding measurements of bioaerosols to include specific measurements of pathogenic bacteria and fungi which were isolated in this study and previous studies, other bioaerosols such as protozoa, viruses, and non-culturable bioaerosols, and other facilities which are expected to be sources of bioaerosols, and hence practical and appropriate control measures can be applied. Moreover, an international standard for monitoring bioaerosols in WWTPs is needed to make the comparison with previous studies more significant. Also, more comparative studies are needed to confirm the accuracy of the Omeliansky formula or to modify/replace it so that measurements using the sedimentation method will be more accurate.

Several precautions can be used to decrease risk of exposure to bioaerosols emitted from the WWTP such as the inactivation of pathogenic bioaerosols in closed workplaces, using of ventilation systems, automating whenever available, applying WWTP main processes only during daylight hours when the inactivation and dilution of airborne pathogens are highest, and considering a safe distance between the WWTP and the residential areas in future urban planning.

Data availability

Sequences was deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and their accession numbers are: PQ164272: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164272, PQ164273: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164273, PQ164282: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164282, PQ164283: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164283, PQ164289: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164289, PQ164339: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164339, PQ164341: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164341, PQ164346: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164346, PQ164347: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ164347.

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Healthy Environments for Healthier Populations: Why do they matter, and what can we do? https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/325877 (2019).

Dwevedi, A. Solutions to Environmental Problems Involving Nanotechnology and Enzyme Technology. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2016-0-04550-3 (Elsevier, 2019).

Vallero, D. Fundamentals of Air Pollution 4th edn (Elsevier, 2008).

Lindsley, W. G. et al. Sampling and characterization of bioaerosols. In NIOSH Manual of Analytical Methods (NMAM), 5th edn (2017). https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/nmam/pdf/chapter-ba.pdf.

Jonsson, P., Olofsson, G. & Tjärnhage, T. Bioaerosol detection technologies. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-5582-1 (Springer, 2014).

Yao, M. & Bioaerosol A bridge and opportunity for many scientific research fields. J. Aerosol Sci. 115, 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2017.07.010 (2018).

Can-Güven, E. The current status and future needs of global bioaerosol research: a bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 19, 7857–7868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-021-03683-7 (2022).

Sharma Ghimire, P., Tripathee, L., Chen, P. & Kang, S. Linking the conventional and emerging detection techniques for ambient bioaerosols: a review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 18(3), 495–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11157-019-09506-z (2019).

Douglas, P., Robertson, S., Gay, R. & Hansell, A. L. Gant. T. W. A systematic review of the public health risks of bioaerosols from intensive farming. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 221, 134–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.10.019 (2018).

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/ (2024).

Wolfe, E. K. Quantitative characterization of Aerosols. Bacteriol. Rev. 25(3), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1128/br.25.3.194-202.1961 (1961).

Przystaś, W., Zabłocka-Godlewska, E. & Melaniuk-Wolny, E. A. Comparison of sedimentation method and active sampler analysis of microbiological indoor air quality—case study. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S30, 1. https://doi.org/10.2478/eces-2023-0009 (2023).

Abdel Hameed, A. & Habeeballah, T. Air microbial contamination at the Holy Mosque, Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Curr. World Environ. 8, 179–187. https://doi.org/10.12944/CWE.8.2.03 (2013).

Cartwright, C., Horrocks, S., Kirton, J. & Crook, B. Review of methods to measure bioaerosols from composting sites. Environment Agency. London, United Kingdom. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/291531/scho0409bpvk-e-e.pdf (2009).

Michalkiewicz, M. Wastewater treatment plants as a source of bioaerosols. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 28(4), 2261–2272. https://doi.org/10.15244/pjoes/90183 (2019).

Viani, I. et al. Passive air sampling: the use of the index of microbial air contamination. Acta Biomed. 91, 92–105. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i3-S.9434 (2020).

Awad, A. H. & Abdel Mawla, H. Sedimentation with the Omeliansky Formula as an accepted technique for quantifying Airborne Fungi. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 21(6), 1539–1541 (2012). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288723072_Sedimentation_with_the_Omeliansky_Formula_as_an_Accepted_Technique_for_Quantifying_Airborne_Fungi

Manibusan, S. & Mainelis, G. Passive bioaerosol samplers: A complementary tool for bioaerosol research. A review. J Aerosol Sci 2022, 163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaerosci.2022.105992 (2022).

Hayleeyesus, S. F. & Manaye, A. M. Microbiological quality of indoor air in university libraries. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 4, S312–S317. https://doi.org/10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C807 (2014).

Sundri, M. I. Bacteria and Fungi levels in crowded indoor areas. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 12(9), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.9790/2402-1209013945 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Assessment of culturable airborne bacteria of indoor environments in classrooms, dormitories and dining hall at university: a case study in China. Aerobiologia 36(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10453-020-09633-z (2020).

Stefanović, O. D., Radosavljević, J. D. & Kosanić, M. M. Microbiological indoor air quality in faculty’s rooms: risks on students’ health. Kragujevac J. Sci. 43, 63–72. https://doi.org/10.5937/KgJSci2143063S (2021).

Oulkheir, S. et al. Assessment of microbiological indoor air quality in a public hospital in the city of Agadir, Morocco. Period Biol. 123(1–2), 29–34. https://doi.org/10.18054/pb.v123i1-2.6461 (2021).

Korzeniewska, E. et al. Determination of emitted airborne microorganisms from a BIO-PAK wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 43(11), 2841–2851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2009.03.050 (2009).

Gotkowska-Plachta, A. et al. Airborne microorganisms emitted from Wastewater Treatment Plant Treating Domestic Wastewater and Meat Processing Industry Wastes. Clean. - Soil. Air Water 41(5), 429–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/clen.201100466 (2013).

Aborawash, S., Fouad, M., El-Gamal, H. & Radwan, K. Effect of plants, shading and solar radiation on bioaerosol in wastewater treatment plants. Int. Water Technol. J. 9, 1. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.11574.34885 (2019).

Kshikhundo, R. & Itumhelo, S. Bacterial species identification. World News Nat. Sci. 3, 26–38 (2016). http://www.worldnewsnaturalsciences.com/article-in-press/2016-2/

Sunpapao, A. et al. Morphological and molecular identification of plant pathogenic fungi associated with dirty panicle Disease in coconuts (Cocos nucifera) in Thailand. J. Fungi 8, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof8040335 (2022).

Church, D. L. et al. Performance and application of 16S rRNA gene cycle sequencing for routine identification of bacteria in the clinical microbiology laboratory. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 33(4), 1–74. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00053-19 (2020).

Singh, N. K., Yadav, S. G., Padhiyar, M., Thanki, A. & H., & A state-of-the-art review on WWTP associated bioaerosols: microbial diversity, potential emission stages, dispersion factors, and control strategies. J. Hazard. Mater. 410, 124686. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124686 (2021).

Alexandria Sanitary Drainage Company (ASDCO). Home Page. https://asdcoeg.com (2022).

SUEZ. Alexandria Wastewater Treatment Plant. https://www.suezwaterhandbook.com/content/download/5669/90770/version/2/file/Alexandria_EN_A4.pdf (2008).

Pasquarella, C., Pitzurra, O. & Savino, A. The index of microbial air contamination. J. Hosp. Infect. 46(4), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1053/jhin.2000.0820 (2000).

Muangsue, N. & Amimanan, P. Determination of airborne bacteria and fungi in the laboratories of a university. Naresuan Phayao J. 11(2), 52 (2018). https://li01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/journalup/article/view/184767

Vanlalruati, R. S. C. et al. Microbiological surveillance of operation theatres of a tertiary care hospital in Mizoram, north eastern part of India: 4 years retrospective analysis. IP Int. J. Med. Microbiol. Trop. Dis. 8 (1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.18231/j.ijmmtd.2022.005 (2022).

Mandal, J. & Brandl, H. Bioaerosols in indoor environment—a review with special reference to residential and occupational locations. Open. Environ. Biol. Monit. J. 4(1), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2174/1875040001104010083 (2011).

Fekadu, S. & Getachewu, B. Microbiological assessment of indoor air of teaching hospital wards: a case of Jimma University Specialized Hospital. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 25(2), 117. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v25i2.3 (2015).

Nevalainen, A. Bacterial aerosols in indoor air [University of Kuopio]. https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/134619/Bacterial%20Aerosols%20in%20indoor%20air.pdf?sequence=1 (1989).

Cappitelli, F. et al. Chemical-physical and microbiological measurements for indoor air quality assessment at the ca’ granda historical archive, Milan (Italy). Wat Air Soil. Poll. 201(1–4), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-008-9931-5 (2009).

Yang, K. et al. Airborne bacteria in a wastewater treatment plant: Emission characterization, source analysis and health risk assessment. Water Res. 149, 596–606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2018.11.027 (2019).

Abel, E. et al. The Swedish key action The Healthy Building—research results achieved during the first three years period 1998–2000. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Swedish-key-action-%27The-Healthy-Building%27-the-Abel-Andersson/6902afa88b437d180100c821d5c13452bb4b75d3 (2002).

Stryjakowska-Sekulska, M., Piotraszewska-Pająk, A., Szyszka, A., Nowicki, M., Filipiak, M. & & Microbiological quality of indoor air in University rooms. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 16(4), 623–632 (2007). http://www.pjoes.com/Microbiological-Quality-of-Indoor-Air-r-nin-University-Rooms8803002.html.

Wanner, H. U. Biological Particles in Indoor Environments. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/859b1f78-ea84-44a1-a045-c230c2283c9e (1993).

Hall, T. A. BioEdit: A user-friendly Biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/ NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 (1999).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215(3), 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 111. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38(7), 3022–3027. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab120 (2021).

Michałkiewicz, M. Comparison of wastewater treatment plants based on the emissions of microbiological contaminants. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190, 11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-7035-2 (2018).

Han, Y. et al. Bacterial population and chemicals in bioaerosols from indoor environment: Sludge dewatering houses in nine municipal wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 618, 469–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.071 (2018).

Pascual, L. et al. Bioaerosol emission from wastewater treatment plants. Aerobiologia 19, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AERO.0000006598.45757.7f (2003).

Oppliger, A., Hilfiker, S., Duc, T. V. & & Influence of seasons and sampling strategy on assessment of bioaerosols in sewage treatment plants in Switzerland. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 49(5), 393–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/annhyg/meh108 (2005).

Sánchez-Monedero, M. A., Aguilar, M. I., Fenoll, R. & Roig, A. Effect of the aeration system on the levels of airborne microorganisms generated at wastewater treatment plants. Water Res. 42(14), 3739–3744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2008.06.028 (2008).

Heinonen-Tanski, H., Reponen, T. & Koivunen, J. Airborne enteric coliphages and bacteria in sewage treatment plants. Water Res. 43(9), 2558–2566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2009.03.006 (2009).

Haas, D. et al. Exposure to bioaerosol from sewage systems. Water Air Soil. Poll. 207(1–4), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-009-0118-5 (2010).

Vítězová, M., Vítěz, T., Mlejnková, H. & Lošák, T. Microbial contamination of the air at the wastewater treatment plant. Acta Universitatis Agric. Silvicult. Mendelianae Brunensis 60(3), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.11118/actaun201260030233 (2012).

Teixeira, J. et al. Assessment of indoor airborne contamination in a wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Monit. Assess. 185(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-012-2533-0 (2013).

Ding, W., Li, L., Han, Y., Liu, J. & Liu, J. Site-related and seasonal variation of bioaerosol emission in an indoor wastewater treatment station: level, characteristics of particle size, and microbial structure. Aerobiologia. 32(2), 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10453-015-9391-5 (2016).

Katsivela, E., Latos, E., Raisi, L., Aleksandropoulou, V. & Lazaridis, M. Particle size distribution of cultivable airborne microbes and inhalable particulate matter in a wastewater treatment plant facility. Aerobiologia 33(3), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10453-016-9470-2 (2017).

Kowalski, M. et al. Characteristics of airborne bacteria and fungi in some Polish wastewater treatment plants. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 14(10), 2181–2192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-017-1314-2 (2017).

Dehghani, M. et al. Seasonal variation in culturable bioaerosols in a wastewater treatment plant. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 18(11), 2826–2839. https://doi.org/10.4209/aaqr.2017.11.0466 (2018).

Han, Y., Yang, K., Yang, T., Zhang, M. & Li, L. Bioaerosols emission and exposure risk of a wastewater treatment plant with A2O treatment process. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 169, 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.11.018 (2019).

Li, P., Li, L., Wang, Y., Zheng, T. & Liu, J. Characterization, factors, and UV reduction of airborne bacteria in a rural wastewater treatment station. Sci. Total Environ. 751, 785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141811 (2021).

Ziganshina, E. E. et al. Draft genome sequence of Brevibacterium epidermidis EZ-K02 isolated from nitrocellulose-contaminated wastewater environments. Data Brief. 17, 119–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2017.12.053 (2018).

Niazi, S. et al. Assessment of bioaerosol contamination (bacteria and fungi) in the largest urban wastewater treatment plant in the Middle East. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 22(20), 16014–16021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-015-4793-z (2015).

Uhrbrand, K., Schultz, A. C., Koivisto, A. J., Nielsen, U. & Madsen, A. M. Assessment of airborne bacteria and noroviruses in air emission from a new highly-advanced hospital wastewater treatment plant. Water Res. 112, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2017.01.046 (2017).

Morioka, H. et al. Lysinibacillus fusiformis bacteremia: case report and literature review. J. Infect. Chemother. 28, 315–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2021.10.030 (2022).

Płoszaj, J., Talik, E., Piotrowska-Seget, Z. & Pastuszka, J. S. Physical and chemical studies of bacterial bioaerosols at wastewater treatment plant using scanning electron mikroscopy and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Sol St Phenom. 186, 32–36. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/SSP.186.32 (2012).

Tewari, A. & Abdullah, S. Bacillus cereus food poisoning: international and Indian perspective. J. Food Sci. Technol. 52(5), 2500–2511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-014-1344-4 (2015).

Majumdar, S., Priyadarshinee, R., Kumar, A., Mandal, T. & Dasgupta Mandal, D. Exploring Planococcus sp. TRC1, a bacterial isolate, for carotenoid pigment production and detoxification of paper mill effluent in immobilized fluidized bed reactor. J. Clean. Prod. 211, 1389–1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.157 (2019).

Huang, C. Extensively drug-resistant Alcaligenes faecalis infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 20(1), 833. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05557-8 (2020).

Fox, G. E., Wisotzkey, J. D. & Jurtshuk, P. How close is close: 16S rRNA sequence identity may not be sufficient to guarantee species identity. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42(1), 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-42-1-166 (1992).

Korzeniewska, E. & Harnisz, M. Culture-dependent culture-independent methods in evaluation of emission of enterobacteriaceae from sewage to the air and surface water. Wat Air Soil. Poll. 223(7), 4039–4046. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11270-012-1171-z (2012).

Patentalakis, N., Pantidou, A. & Kalogerakis, N. Determination of enterobacteria in air and wastewater samples from a wastewater treatment plant by Epi-fluorescence microscopy. Water Air Soil. Pollut Focus. 8(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11267-007-9135-9 (2008).

Zhang, M. et al. Quantification of multi-antibiotic resistant opportunistic pathogenic bacteria in bioaerosols in and around a pharmaceutical wastewater treatment plant. J. Environ. Sci. 72, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jes.2017.12.011 (2018).

Mueller, M. & Tainter, C. R. Escherichia Coli. In StatPearls. (2022). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564298/

Denkovskienė, E. et al. Broad and efficient control of Klebsiella pathogens by peptidoglycan-degrading and pore-forming bacteriocins klebicins. Sci. Rep. 9, 15422. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-51969-1 (2019).

Chaitanya, K. V. M. S., Masih, H. & Abhiram, P. Isolation of Trichoderma harzianum and evaluation of antagonistic potential against Alternaria alternata. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 7(10), 2910–2918. https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2018.710.338 (2018).

de Hoog, G. S. et al. Atlas of clinical fungi (4th ed). https://www.clinicalfungi.org/ (2020).

Gautam, A. & Bhadauria, R. Characterization of aspergillus species associated with commercially stored triphala powder. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 11(104), 16814–16823. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB11.2311 (2012).

Pitt, J. I. & Hocking, A. D. Fungi & Spoilage. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-92207-2 (Springer, 2009).

Sciortino, C. V. Atlas of Clinically Important Fungi. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119069720 (Wiley, 2017).

Grisoli, P. et al. Assessment of airborne microorganism contamination in an industrial area characterized by an open composting facility and a wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Res. 109(2), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2008.11.001 (2009).

Li, L., Gao, M. & Liu, J. Distribution characterization of microbial aerosols emitted from a wastewater treatment plant using the Orbal oxidation ditch process. Process. Biochem. 46(4), 910–915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procbio.2010.12.016 (2011).

Szulc, J. et al. Microbiological and toxicological hazards in sewage treatment plant bioaerosol and dust. Toxins. 13(10), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins13100691 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Chemicals and microbes in bioaerosols from reaction tanks of six wastewater treatment plants: survival factors, generation sources, and mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 9362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-27652-2 (2018).

Korzeniewska, E. Emission of bacteria and fungi in the air from wastewater treatment plants-a review. Front. Biosci. 3, 393–407. https://doi.org/10.2741/s159 (2011).

Walsh, T. J., Hayden, R. T. & Larone, D. H. Larone’s medically important fungi. In Larone’s medically important Fungi. https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555819880 (ASM, 2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and are thankful to the administrative and technical staff at the Eastern Wastewater Treatment Plant, Alexandria, Egypt, for facilitating the sampling process.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.E. participated in proposing the research point, supervising the experimental work of quantification and identification of bioaerosols in the atmosphere surrounding the WWTP, and reviewing the final manuscript.E.A.S. participated in proposing the research point, supervising the analysis of the results.M.M.I. participated in preparing sampling design, collecting samples, conducting laboratory analysis, identifying isolated bacterial and fungal colonies, and writing the first draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Authors confirm that all elements of the submission are in compliance with the journal publishing ethics policy and that no ethical approval is required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

El-Bestawy, E., Ibrahim, M.M. & Shalaby, E.A. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of bioaerosols emissions from the domestic eastern wastewater treatment plant, Alexandria, Egypt. Sci Rep 14, 30479 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79645-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79645-z