Abstract

Lagoviruses are viruses of the Caliciviridae family affecting lagomorphs. Both pathogenic and non-pathogenic lagoviruses affect the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus), and they are phylogenetically distinguished. Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus (RHDV/GI.1) and Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease Virus-2 (RHDV-2/GI.2) belong to the first group, while in the second group, several genotypes of Rabbit Calicivirus (RCV/GI.3-GI.4) are present. The first RCV strain was described in Italy in 1996, and since then, several RCV strains have been characterised in Europe and Australia. RCVs, different from the pathogenic hepatotropic RHDVs, have an enteric tropism and could be identified from the duodenum/intestine and faeces. This study aimed firstly to indirectly show through a seroepidemiological survey from 1998 to 2008 the circulation of RCVs strains in rabbit farms and then to genetically characterise RCV strains diagnosed in Italy in faecal and intestinal samples of wild and farmed rabbits collected in various regions in the following years (2000–2022). Of 262 analysed samples, 69 resulted in RT-PCR positive for lagovirus but negative for RHDV. Eleven RCV strains were characterised by complete vp60 sequencing. Phylogenetic analysis showed that the Italian RCV strains are grouped in European (RCV_E1/GI.3) and Australian (RCV_E2/GI.4) RCV clusters, with an estimated country prevalence of 26%. Based on the proposed genotype classification, considering the nucleotide differences of vp60 higher than 15%, we can hypothesise that two other genotypes, GI.5 and GI.6, might exist within the cluster of non-pathogenic viruses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lagoviruses are viruses belonging to the genus Lagovirus within the Caliciviridae family that mostly infect rabbits and hares. Within this viral genus, pathogenic hepatotropic viruses (RHDVs and EBHSVs) that cause acute, fulminant viral hepatitis and completely benign enterotropic viruses (RCVs and HaCVs) can be distinguished.

Lagoviruses are classified based on the nucleotide capsid protein sequences (VP60) into genogroups (e.g. GI and GII), genotypes (e.g. GI.1, GI.2, GI.3 and GI.4), and variants (e.g. GI.1a, GI.1B, GI.1c)1. Rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) is a highly contagious and fatal hepatitis of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). The disease, caused by RHDV (GI.1), was first reported in 1984 in China2 and rapidly spread worldwide, becoming endemic in almost all countries where European rabbits are present as domestic or wild animals3,4. In 2010, a new RHD virus was identified in France5, causing severe outbreaks also in vaccinated adult rabbits and young rabbits that were till then considered typically resistant to RHDV6,7,8. Since the virus is phylogenetically and antigenically distinct from RHDV, it has been called RHDV2 (GI.2). Compared to RHDV, RHDV2 has a more extended host range; in fact, it can infect not only European rabbits (that remains the primary host) but also hares9,10,11,12,13 and other lagomorphs14. The new virus spread all over Europe in a few years, and it is now present worldwide, including Australia15, Africa16 and North and Central America14, where it has become endemic. Indeed, it is now the prevalent RHDV strain and replaced the previous RHDV (GI.1). Another pathogenic lagovirus, genetically and antigenically related to RHDVs that does not infect rabbits, is the causative agent of European Brown Hare Syndrome (EBHSV/GII.1) mainly observed in European brown hares (Lepus europeaus), characterised by mild nervous symptoms, severe necrotic hepatitis and circulatory dysfunction17,18.

The enterotropic benign lagoviruses, named rabbit calicivirus (RCV/GI.3), represent the third group of lagoviruses. They were first detected in domestic and wild rabbits in Italy in 199619 and then in France20,21, in 2000 in Australia (RCV-A1/GI.4)22 and very recently also in Chile23. Note that the existence of RCV was preliminarily inferred from unexpected serological results obtained in unvaccinated, RHD-free farm rabbit populations19,24,25.

These viruses cause a silent small intestine infection without inducing clinical signs and relevant pathological lesions. A non-pathogenic virus (HaCV/GII.2) was also described in brown hares in Italy, France and Australia26,27,28,29,30. The new proposed nomenclature based on the phylogenetic relationships of the full-length VP60 capsid gene collocates the rabbit non-pathogenic viruses into two distinct genotypes: (a) the European Rabbit Calicivirus, RCV-E1 (GI.3); (b) the Australian RCV-A1 and European RCV-E2 (GI.4). In particular, the RCV-E1 (GI.3) cluster with classical RHDV (GI.1), suggesting that it is more closely related to these pathogenic lagoviruses than the more divergent RCV-A1/RCV-E2, which form a distinct monophyletic branch22,31. While the first Italian RCV (X96868/GI.3) provides a complete cross-immunity to RHDV (GI.1)19, the Australian RCV-A1 (GI.4) does only partially, with up to 50% protection in recently infected rabbits32,33.

The worldwide prevalence of RCVs is not well known. Therefore, it is essential to characterise more of these genotypes, considering that these nonpathogenic viruses are increasingly involved in the evolutionary history of pathogenic viruses. Indeed, RHDV2 (GI.2) emerged from recombination between a non-pathogenic virus as the donor of the nonstructural portion of the genome and an unknown virus as the donor of the structural portion of the genome34. Indeed, recombination in RHDVs is an event frequently detected and considered an important driver of lagoviruses evolution35,36.

This study used serological and molecular approaches to detect and genetically characterise the RCV strains circulating in wild and farmed rabbits in Italy from 2000 to 2022.

Results

Serosurveillance

Table 1 shows the results of the serological examination based on cELISA RHDV on 4202 sera taken in five serological surveys from 1999 to 2008 at slaughterhouses of unvaccinated animals derived from RHD-free herds in Northern, Central, and Southern Italy. Positivities are reported according to the percentage of sera that resulted positive within each group originating from the different farms, sampled one or more times. A group was considered negative when over 95% of the sera were negative. The last column reports the number of farms of origin where consecutive groups showed a marked shift in results (from negative to over 75% positive sera) indicative of the new introduction of the non-pathogenic virus in the between sampling periods.

In the positive herds, in which, as initially stated, signs of disease and mortality have never been observed and reported, the cELISA titres averaged between 1/20 to 1/640, with IgG and IgA even at high titres (> 1/1280). These data suggested viral circulation in the herds of a virus antigenically related to RHDV. This is because the cELISA results reflect the presence mainly of antibodies specific to the outer shell of the virion, i.e. the P2 sub-domain of VP60. IgG ELISA results also depend on antibodies-specific epitopes buried in the virus structure, i.e. the S domain and the P2 sub-domain of the VP60, common to different lagoviruses.

A serological pattern similar to that obtained from slaughtered rabbits, i.e., low-medium titres in cELISA RHDV and high titres in IgG/IgA RHDV ELISA, was also obtained later in 2012 during the surveillance in the Bergamo farm, either in post-weaned young rabbits or restocking females, which repetitively resulted in seropositive over two years. Indeed, this serological pattern was highly related to that found in the first RCV-positive farm in Italy19,24. In contrast, a different serological pattern was found in the other two farms, the one in Brescia province (Lombardy region, North of Italy) and that in Foggia province (Puglia region, South of Italy), where negative or doubtful (≤ 1/10) cELISA titres were found associated with very high titres (> 1/2560) of IgG toward RHDV. These data indicated the circulation of a lagovirus antigenically distant from both RHDV and RCV-E119,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33 and more likely genetically related to the Australian non-pathogenic lagovirus (RCV-A1/E2)22 and with the European RCV-E2 (GI.4)1.

Overall, the serological results from the serosurveys conducted in the slaughterhouses were then considered the conceptual basis on which we planned the following study aimed to achieve RCVs detection in farms. In addition to several samplings performed in those provinces where seropositivity was found, we also selected and repetitively checked three farms.

Genome sequencing and phylogenesis of RCV isolates in Italy from 2000 to 2022

Of the 262 analysed samples taken from 2000 to 2022, following the previous serosurveillance studies, 69 were RT-PCR positive for lagovirus and negative for RHDVs, with an estimated country prevalence of 26%. Among the 69 positives, we obtained multiple detections in the same farm in four cases in VR province in 2007, two in MC province in 2008, 32 in PN province in 2012, four in BG province in 2015, and three in LC province in 2015. The remaining 24 positives were singly detected in as many farms.

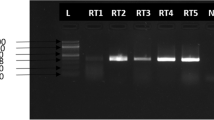

Eleven lagovirus-positive samples were confirmed to be RCVs by complete VP60 sequencing (Fig. 1).

Phylogenetic analysis based on vp60 sequences (Fig. 2) showed that the RCV strains detected in different Italian regions were basically grouped in both the European (RCV-E1/GI.3) and Australian-like (RCV-E2/GI.4) RCV clusters.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree performed for the structural genes VP60 (nucleotides 5240–6869; nucleotide substitutions model GTR + G + I). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Support for each cluster was obtained from 1.000 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values > 70% are shown. Genotype clusters, which do not include viruses sequenced in this study, were collapsed and annotated accordingly.

Five strains were provisionally classified as RCV-E1, and they originated from three provinces (RCV/Italy/BS2000; RCV/Italy/BS2007; RCV/Italy/MC2008; RCV/Italy/BG2012; RCV/Italy/BG2015).

On the farm in the BS province, where we found in 1996 the first non-pathogenic virus, the RCV “Italian” strain (X96868), two additional RCVs were identified after several years of interval. However, with respect to the original strain, these strains showed a nucleotide identity of 98.99% (RCV/Italy/BS2000) and 90.49% (RCV/Italy/BS2007). On a farm in the BG province, we found two RCVs (RCV/Italy/BG2012 and RCV/Italy/BG2015) three years apart. These strains are phylogenetically very similar to the RCV-E1 group described in France1,20. Still, between them, we detected only 84.40% nucleotide identity.

RCV/Italy/BS2000; RCV/Italy/BS2007; RCV/Italy/MC2008 were also characterised by a deletion of one amino acid in position 301 and two amino acid deletions at positions 309–310, already described in the first Italian RCV (X96868)19. These last two deletions were also observed in strains belonging to the GI.3 genotype, both the French and the Italian strains described in this study, except RCV/Italy/BG2015, which presented only the 310 aa deletion.

Six viruses originating from four different provinces: FG (RCV/Italy/FG2013 and RCV/Italy/FG2016), PN (RCV/Italy/PN2012_1 and RCV/Italy/PN2012_2), BS (RCV/Italy/BS2010), and FC (RCV/Italy/FC2017) were phylogenetically related to the Australian strains (RCV-E2/GI.4)22. They were detected either in geographically distant farms (Fig. 1) at different times, i.e., RCV/Italy/BS2010, RCV/Italy/PN2012_1 and RCV/Italy/PN2012_2, RCV/Italy/FG2013 and RCV/Italy/FG2016, and from feral rabbits (RCV/Italy/FC2017). Indeed, the two strains identified in the same farm in FG province three years apart (RCV/Italy/FG2013 and RCV/Italy/FG2016), presented a nucleotide identity of 98%.

Note that four of these strains (RCV/Italy/BS2010, RCV/Italy/PN2012_2, RCV/Italy/FG2013 and RCV/Italy/FG2016) showed only ≈ 83% nt identity with the known strains belonging to the GI.4 genotype1. In fact, these RCVs were closer to the RCV identified in Chile in 202123. The other two strains (RCV/Italy/FC2017 and RCV/Italy/PN2012_1), also belonging to the RCV-E2/GI.4 genogroup, were phylogenetically closer to the strains identified in France between 2008 and 2015 (LT708121-LT708130)1.

Full genome analysis

The full genome sequence obtained from the RCV/Italy/BS2000 strain was 7380 nucleotides (nt) in length, and sequence analysis with reference strains showed the typical genomic organisation of lagoviruses, with two overlapping open reading frames (ORFs). The complete 5′ end was not obtained and was based on inference with the French strain RCV-GI.3/06-11 (GB MN737115), with an estimated 47 nt likely missing. Potential cleavage sites described for the polyprotein processing are conserved, except for E367/D36821. The ORF2 encodes for a putative 113 aa protein, similar to RCV-GI.3/06-11 and other lagoviruses.

The nucleotide and amino acid identity comparison of the non-structural proteins and genes (NS) of RCV/Italy/BS2000 with other representative rabbit lagoviruses is indicated in Fig. 3, panel A, showing the highest nt identity of 87.64% with a recombinant GI.x/GI.1 strain identified in Portugal in 199437. Phylogenetic analysis performed with the same region showed that RCV/Italy/BS2000 belongs to a phylogenetically distinct genetic group very close to the viruses identified in the 1990s on the Iberian Peninsula (Fig. 3, panel B)37. In addition, to investigate a possible recombination event, a SimPlot and RDP4 analysis was performed with full genome sequences. Still, no evidence of recombination with other known lagoviruses was detected (data not shown).

ORF1 NS genome analysis using a dataset of 139 lagoviruses present in GenBank (48nt-5239nt). (A) Nucleotide and amino acid identity values relative to the NS genes/proteins of RCV/Italy/BS2000, with representative strains of rabbit pathogenic and non-pathogenic lagoviruses (RCV-E1, RCV-E2 and RHDV). (B) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree performed with the nucleotide substitution model (GTR + G + I); The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Support for each cluster was obtained from 1.000 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap values > 70% are shown. Genotype clusters, which do not include virus variants sequenced in this study, were collapsed and annotated accordingly. The Italian sequence reported in this work is indicated (RCV/Italy/BS2000).

Discussion

This study covers an extensive period of about two decades and a large territory, including several Italian regions, during which we investigated the presence of non-pathogenic rabbit lagoviruses (RCVs). We first performed a serological approach by using different ELISA tests with the aim of broadly assessing the presence and consistency of distribution of RCVs, mainly in farmed rabbits. The choice to test fattening rabbits at slaughterhouses was consistent with the initial detection of RCV in the faecal materials of 40–60-day-old growing rabbits19 and with the proposed epidemiological pattern of RCVs in farmed conditions24.

Five separate surveys were conducted in different periods and regions. Overall, we found quite a high number of farms with positive antibody titres (37.8% range 19.1–52.2%), thus confirming a consistent circulation of RCVs. Indeed, we found two patterns of antibody profile, suggesting the circulation in Italy of antigenically distinct RCV strains, one more related to RHDV (RCV-E1/GI.3), and the other one more similar to the non-pathogenic rabbit calicivirus first identified in Australia/New Zealand (RCV-E2/GI.4)22, then in France1 and very recently in Chile23. Specifically, the combined use of two serological methods, the cELISA-RHDV and IgG-RHDV-ELISA, allowed for inferring the existence of RCVs with varying degrees of antigenic similarity to the pathogenic RHDV. In the presence of any RCVs, the sera were positive with high titers by the IgG-RHDV-ELISA, due to the ability of this test to detect also antibodies produced against the internal VP60 common epitopes shared by all lagoviruses. At the same, whereas the cELISA-RHDV could detect the antibodies induced by RCVs identified in Europe (RCV-E1/GI.3), due to the very similar antigenic profile of these two viruses, in contrast, this test poorly detected the antibodies against Australian-like RCVs (RCV-E2/GI.4), which have an antigenic profile very different from RHDV.

Starting from the serological evidence of a widespread circulation of RCV strains in the national territory, and from indications that they could be even different from one another, our research then focused on the viral detection and characterisation of RCV strains. Accordingly, by conducting a series of serological surveys in intensive units, we then further confirmed the circulation patterns of RCVs, as previously described by Capucci et al.24. The optimal sampling scheme for viral identification was to take faecal and intestinal samplings from growing rabbits of 40–60 days of age. In fact, this resulted in the most frequent time for their infection through the faecal-oral route, following contact with infected fomites, likely of maternal origin24.

In general, the RT-PCR results confirmed the serological data indicating the presence of RCVs. Indeed, it was more challenging to demonstrate a real new introduction since the number of multiple samplings of both sera and faecal materials from the same farm was very low. In particular, we had the opportunity to verify in one farm (the same in which RCV was first identified in 1996) the persistence of antibodies in growing rabbits for more cycles and at least two further viral detections in 2000 and 2007 of two genetically different strains, likely indicating a new introduction at the second checking time.

The relationship between the results of serosurveillance and the virologic investigation, which indeed covers different periods, was very low and mainly represented by the overlapping of the checked areas. However, the five examinations of sera batches at the slaughterhouses were helpful in assessing the compelling presence and circulation of RCVs in Italian farms. Still the study was not explicitly planned to detect at the same time the presence in the corresponding farm of the RCV viral strains. In fact, such a study started when we had certainty following the serological results of a widespread presence of RCVs.

The 262 faecal and duodenal samples globally harvested during the period 2000–2022 were analysed with molecular methods able to detect any lagovirus and 69 of them were positive by RT-PCR for RCV. All these positive samples were further processed for the full vp60 sequencing. However, we succeeded in amplifying and sequencing the entire vp60 for only 11 of these strains. We were unable to complete gene amplification for the rest of the samples, likely due to insufficient viral RNA amounts27,30.

The vp60 phylogenetic analysis of these eleven strains confirmed the hypotheses suggested by the serological results, i.e., the contemporary presence and circulation of both the European (RCV-E1/GI.3) and Australian-like (RCV-E2/GI.4) RCVs in Italy. Interestingly the two GI.3 strains identified were originating from the same farm in BG province (Lombardy region) at three years apart. Still, their genomic identity was relatively low, thus suggesting that these strains were different variants rather than the persistence and evolution of the same strain. In addition, the two strains resulted strictly related to RCV-E2, i.e. belonging to the GI.4 genotype, were distant both geographically (PN province in North Italy vs. FC province in Central Italy) and temporarily (2012 vs. 2017) as well as origin (farmed vs. feral rabbit, respectively).

Moreover, with respect to the two known RCV genotypes (RCV-E1/GI.3 and RCV-E2/GI.4), the nucleotide differences of vp60 genes of the other seven viruses identified in this study were greater than 15%. This data led us to consider the existence of two additional different genotypes, GI.5 and GI.6. Within the RCVs cluster. Indeed, in the proposed genetic classification of lagoviruses1, GI.5 was already identified as a putative genotype since only one sequence was reported at that time19. Therefore, we suggest fixing GI.5 as the genotype for the first detected RCV in Italy (X96868), which should also include two additional variants identified in the same farm in the BS province (North Italy) in 2000 and 2007 and one strain identified in 2008 in the MC province (Central Italy). Considering the nucleotide identity of the variant isolated in 2000 compared to the one detected in 2007 in the Brescia farm, either an evolution of the original strain or a new introduction of a strictly related strain might have occurred. The genetic variability of the nonpathogenic lagoviruses identified in Italy was even more evident considering that the last four identified RCVs were clustering separately from the other RCV-A1-like strains (RCV-E2/GI.4) and more closely related to the RCVs found recently in Chile23. Thus, we agree with the Authors of that study when suggesting the European origin of their strains. Still, it also led us to retain that these variants, clustering together, could represent a new genotype (GI.6). In this case also, the strains were detected over quite a long period (2010–2016) respectively in two farms in Northern Italy, i.e. in 2010, the farm in BS province where rabbits were reared for vaccine production and in 2012 in an intensive farm in North-East Italy (PN province), and twice (2013 and 2016) in one breeding farm in South Italy (FG province), suggesting the likely persistence of the same strain considering the very high nucleotide identity.

This study shows that RCVs have been present in Italy since they were first identified, but their presence in rabbit herds probably dates back much longer. This last hypothesis is supported by the serological detection of anti-lagovirus antibodies in sera from healthy rabbit groups in the Czech Republic and historical collections dating back to the 1970s25. In addition, the capacity of RCV-E1 (i.e. GI.3 and the suggested GI.5) to act as a natural vaccine against RHD by inducing cross-reactive antibodies, partially protective against RHDV19 could also partially explain why, when the first RHD epidemic occurred in 1986 in Northern Italy, the disease was observed mainly in rural farms and less in industrial ones where RCVs were likely already present and diffused thanks to the type of management and production cycle (Lavazza personal communication).

The RCV identifications that we obtained, even considering the low success in amplification and sequencing (about 16% of the RT-PCR positives), confirmed that they are likely present at low concentration and/or for a very short period in infected animals but that they can both remain as such for a long time in the same holding as well as evolve minimally or even significantly. In this regard, based on the data collected, having shown for some strains a nucleotide divergence of over 15% with the already known strains1, we consider that an implementation of the classification of non-pathogenic lagoviruses into four distinct genotypes might be justified.

Another aspect arising from our study is the wide variability in the distribution of RCV strains on Italian territory, some of which are very similar to each other and to strains identified both in Europe and on other continents. This is most likely due to the frequent and extensive commercial exchanges with a few companies producing genetic lines of rabbits distributed worldwide, which are usually vaccinated for RHD, clinically checked but not systematically examined for the presence of non-pathogenic lagoviruses.

At the same time, the identification of at least one strain in feral rabbits suggests that RCVs may also be present outside the commercial circuit. Moreover, this phenomenon has already been observed and consolidated in the brown hare (Lepus europaeus). In fact, the non-pathogenic hare Calicivirus (HaCV) antigenically related to the pathogenic hare virus EBHSV and classified as genotype GII.2 was identified in domestic and wild hares in Italy, Europe and Australia26,27,28,29,30.

The results of the combined use within a farm of different serological methods for RHD, including Isotype ELISAs and the cELISA, to test the presence of antibodies in fattening rabbits of any age and from those > 8 weeks old born from vaccinated does, raise suspicion of the presence of an RCV. This is quite certain when positive titres, with one of the two described patterns, are found in rabbits from herds that have not been affected by RHD for at least 3 to 4 months. Still, it could also be true when non-vaccinated rabbits are tested for other reasons, e.g. for checking sentinels after an RHD outbreak, finalised to check the absence of pathogenic virus after disinfection procedures and emergency vaccination, as stated by Italian legislation. In addition, based on the type of antibodies’ pattern: i.e., (1) low-medium titres in cELISA-RHDV and high titres in IgG/IgA-RHDV-ELISA, or (2) negative or doubtful cELISA-RHDV and very high titres of IgG-RHDV-ELISA, a presumptive diagnosis of the RCV type (RCV-E1/GI.3/GI.5 vs RCV-E2/GI.4/GI.6) could be posed. Nevertheless, virus identification and characterisation through vp60 amplification and sequencing are necessary to ascertain exactly which RCV is present. Otherwise, in the case of not well-defined serological results, only genetic analysis can confirm the presence of RCV unless a specific serology for RCV is developed, as done for RCV-A1 by Australian authors38.

Of note is the fact that the non-structural portion of the only virus we have a full genome sequence, which is strictly related to the first RCV identified in 1996 in Italy, fell within the same monophyletic group of old strains identified in Portugal37. Unfortunately, in the absence of other complete lagovirus sequences of the GI.1 genotype, this evidence can only suggest the existence of a common non-pathogenic ancestor from which both the RCV/BS2000 and, following a recombination event, the pathogenic viruses identified in Portugal in 199437 likely originated.

In conclusion, the results obtained in this study improve our understanding of the evolution of pathogenic lagoviruses, potentially originating from non-pathogenic strains. It is now proven that RHDV2 (GI.2) emerged from a recombination event between a non-pathogenic virus and an unknown “new” calicivirus. As highlighted by several researchers, expanding the sequencing of the full genome of non-pathogenic viruses is crucial for a comprehensive knowledge of the evolutionary history and genetic diversity within this viral genus.

Materials and methods

Sampling

From 1999 to 2008, five serological surveys were conducted at slaughterhouses on unvaccinated animals from farms in Northern, Central, and Southern Italy (Fig. 4). Almost all sera were collected from rabbits with an average age of about 10–12 weeks belonging to RHD-free herds. When possible, the farms were repeatedly controlled over about six months, a variable number of times, to verify the persistence of the infection. Each sampled group consisted of a minimum of 10 and a maximum of 60 sera.

The first study was conducted in 1999 in a large slaughterhouse located in Lombardy, where animals from rabbit-intensive farms in Lombardy and Triveneto (Veneto, Friuli-Venezia-Giulia and Trentino-Alto-Adige) were commonly slaughtered. At least 10–15 blood samples were taken at the slaughterhouse for each group, and a total of 39 groups of rabbits from as many farms were sampled.

The second survey was conducted between June 2002 and March 2003 in five different slaughterhouses in Campania, where rabbits from intensive or semi-intensive farms in Campania, Basilicata and Lazio were usually slaughtered. Forty-five rabbit groups (1786 sera) were sampled from 21 different holdings, each holding being checked at least once, up to a maximum of four times.

The third study was conducted in 2004 in a slaughterhouse in the Marche region, where rabbits from farms in the same area were slaughtered. Each holding was monitored once, and at least 30 blood samples were taken from each group slaughtered. A total of 831 sera were taken from 23 groups of rabbits from as many holdings.

The fourth survey was conducted in 2006–07 at the same slaughterhouse in the Marche region as the third survey. Twenty-one farms in Central Italy were analysed. Each holding, except two, was monitored through a single sampling ranging from 12 to 33 sera for 555 samples.

The fifth and last survey was conducted in 2007–08 in a slaughterhouse in the province of Brescia (Lombardy region). Groups of rabbits from 13 farms in Lombardy (3 Brescia and 3 Mantua) and Veneto (Verona 6 and Padua 1) were slaughtered. Sampling took place over 4–5 months; on average, each farm was sampled 3–5 times. A total of 500 sera were taken from 50 groups of rabbits.

The details of the sera sampled are reported in Table 2.

For different reasons, other serological surveys were conducted on rabbits within intensive units in the following years. One purpose of the serological surveys was to identify farms where the RCV viruses were circulating to plan a specific investigation for detecting the viral agent. Therefore, in some of these farms, from 2000 to 2022, we asked farmers to collect samples (faeces and/or intestinal contents) from post-weaned animals aged 40–60 days. We also included in the sampling plan the farm in which we first identified RCV in 199619,24 with the aim of confirming the persistence of viral circulation, we took samples twice (2000 and 2007).

Note that all the sampled animals were not sacrificed for the survey scope, but we took only animals that spontaneously died for other causes. From these, the proximal duodenum, i.e. the first tract of 10–15 cm from the pylorus, was sampled during necropsies. In some cases, faeces from live animals from industrial farms were also collected. Finally, we included in the sampling piece of intestine taken from dead feral rabbits from a city park in Forlì (Emilia-Romagna region) (Table 3).

In particular, three situations were further considered, for the type of results that were highly suggestive of the presence of non-pathogenic lagoviruses. In the first investigated farm in BS province (Lombardy) in 2010, rabbits for vaccine production were reared in controlled conditions. Twelve sera were first taken from selected three-month-old rabbits. Then, after a couple of months, four more rabbits (45 days old) were investigated to confirm the results obtained, and both sera and faecal materials for viral isolation were sampled. The second farm in BG province (Lombardy) was under control, as requested by national rules, after an outbreak of RHDV2 that had occurred one year before. Surveillance was conducted from 2012 to 2014 by taking blood sera from fattening rabbits (35–50 days old) and restocking females (90–120 days old) at five different time points: October 2012, 10 restocking females and 20 fattening rabbits (35 days old); November 2012, 10 restocking females; February 2013, 10 fattening rabbits (50 days old) and 10 restocking females; April 2014, five restocking females; October 2014, five fattening rabbits (40 days old). For viral isolation, fattening rabbits were sampled at a 1.5-year interval; respectively, we took a pool of faecal samples in October 2012, and 12 single duodenal tracts were sampled in March 2014.

Similarly, a sanitary surveillance plan was implemented after a previous RHD outbreak at the last farm, a rabbit breeder industry in FG province (Puglia Region, South of Italy). Five rabbits (four months old) were first sampled in December 2014, and then in February 2015, sera were taken from eight more fattening rabbits and 32 restocking females. For viral isolation, fattening rabbits were sampled for the first time in 2014 (38 faecal samples) and then in 2016 (eight duodenal tracts).

Competition ELISA and Isotype ELISA

Competition ELISA tests (cELISA-RHDV) and isotypes ELISA for RHDV (IsoELISA-RHDV) were performed as previously described36,39,40. In the cELISA-RHDV, the ELISA plate is adsorbed with rabbit IgG purified from a hyperimmune RHDV serum. Subsequently, the test serum is incubated with the pre-titrated RHDV antigen so that the reaction between the virus and rabbit antibodies in the serum occurs in the liquid phase. Finally, an HRP-conjugated anti-RHDV MAb detects the amount of virus captured on the solid phase during the first incubation. Each serum is analysed at an initial dilution of 1/10 and then diluted in four-base three times. A serum is classified as positive for RHDV antibodies if its OD value at 1/10 dilution is lower than 75% of the OD value at the same dilution of the negative control serum.

The IsoELISA comprises three separate ELISAs that specifically detect IgG, IgM and IgA against RHDV40,41. Two different types of ELISA reaction are used to detect respectively IgG and IgM-IgA: 1) quantifying the specific IgG requires the entrapping of the RHDV antigen with an anti-RHDV MAb absorbed on a microplate. The sera are then serially diluted, and the IgG bind to the virus are revealed by an HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG MAb; 2) the quantification of the specific IgM and IgA is obtained by using two different MAbs, anti-rabbit IgM, and anti-IgA respectively, which are directly coated on a microplate on which the sera are diluted. Then, the previously titred RHDV antigen is added and shown with an anti-RHDV HRP-conjugated Mab.

Extraction, detection, and sequencing of viral RNA

Total RNA was extracted from faeces or duodenum27. Pellets were resuspended in PBS buffer (1:5 w/v), soaked at 4 °C and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 30 min; 250 µl of supernatant was recovered for RNA extraction using the Trizol reagent (Qiagen, Hilde, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with 5 µλ of RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA). To detect the viral RNA, a first PCR was performed using the universal primers for lagovirus Rab1/Rab222. The entire VP60 gene was amplified using several overlapping PCRs using newly designed primers for the genome of lagovirus (Table 4) with the SuperScript® III One-Step RT-PCR System with Platinum® Taq High Fidelity (Life Technologies Carlsbad, USA) and the products were gel purified (Machery Nagel, Germany) and sequenced. The DNA sequences were determined with an ABI Prism 3500 Series Genetic Analysers in both directions (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using the PCR primers and the Big Dye Terminator v3.1 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, USA) as recommended by the manufacturer. Contig assembling and genome sequence analysis were done using Seqman NGen DNASTAR version 11.2.1 (DNASTAR, Madison, WI, USA).

Phylogenetic analysis was performed using a data set of 123 vp60 sequences (5240nt-6869nt) representing the five genotypes based on the vp60 sequences: GI.1 (n. 68), GI.2 (n. 24), GI.3 (n.6), GI.4 (n.24) and as outgroup GII.1 (n.1), available in GenBank and aligned with MEGA X42

The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and General Time Reversible model. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered is shown next to the branches. Initial trees for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the Maximum Composite Likelihood (MCL) approach and then selecting the topology with superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. Support for each cluster was obtained from 1.000 bootstrap replicates.

Full genome sequence and recombination analysis

A primer-walking strategy was used to obtain a complete genome by overlapping genomic fragments obtained by PCR using primers designed on conserved regions of lagoviruses sequences (Table 4). To obtain the 3’end of the genome, cDNA synthesis was performed using oligo-dTadapter primer followed by PCR using VP607-F/Adapter primers43. The sequence of PCR products was performed as described above. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using a data set of sequences of the nonstructural part of the genome from 139 lagovirus strains available in GenBank and aligned with MEGA X. Moreover, a data set of full genome sequences was screened against the RCV sequence for potential recombination using six methods (RDP, GENECOV, Bootscan, MaxChi, Chimaera, SiScan) implemented in the RdP4 (V. 4.100)44.

Data availability

The raw serological data analysed during this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. All sequences generated in this study were deposited in the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/) under the accession numbers indicated in the text.

Change history

06 February 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-88648-3

References

Le Pendu, J. et al. Proposal for a unified classification system and nomenclature of lagoviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 98, 1658–1666. https://doi.org/10.1099/jgv.0.000840 (2017).

Liu, S. J., Xue, H. P., Pu, B. Q. & Qian, N. H. A new viral disease in rabbits. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest. 16, 253–255 (1984).

Eden, J., Read, A. J., Duckworth, J. A., Strive, T. & Holmes, E. C. Resolving the origin of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus: Insights from an investigation of the viral stocks released in Australia. J. Virol. 89, 12217–12220. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01937-15 (2015).

Morisse, J. P., Le Gall, G. & Boilletot, E. Hepatitis of viral origin in Leporidae: Introduction and aetiological hypotheses. Rev. Sci. Tech. 10, 269–310 (1991).

Le Gall-Recule, G. et al. Detection of a new variant of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus in France. Vet. Rec. 168, 137–138. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.d697 (2011).

Le Gall-Recule, G. et al. Emergence of a new lagovirus related to rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus. Vet. Res. 44, 81. https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-44-81 (2013).

Dalton, K. P. et al. Variant rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus in young rabbits, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18, 2009–2012. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1812.120341 (2012).

Dalton, K. P., Nicieza, I., Abrantes, J., Esteves, P. J. & Parra, F. Spread of new variant RHDV in domestic rabbits on the Iberian Peninsula. Vet. Microbiol. 169, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.12.015 (2014).

Camarda, A. et al. Detection of the new emerging rabbit haemorrhagic disease type 2 virus (RHDV2) in Sicily from rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) and Italian hare (Lepus corsicanus). Res. Vet. Sci. 97, 642–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.10.008 (2014).

Hall, R. N. et al. Detection of RHDV2 in European brown hares (Lepus europaeus) in Australia. Vet. Rec. 180, 121. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.104034 (2017).

Neimanis, A. S. et al. Overcoming species barriers: An outbreak of Lagovirus europaeus GI2/RHDV2 in an isolated population of mountain hares (Lepus timidus). BMC Vet. Res. 14, 367. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-018-1694-7 (2018).

Puggioni, G. et al. The new French 2010 rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus causes an RHD-like disease in the Sardinian Cape hare (Lepus capensis mediterraneus). Vet. Res. 44, 96–96. https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-44-96 (2013).

Velarde, R. et al. Spillover events of infection of Brown Hares (Lepus europaeus) with rabbit haemorrhagic disease type 2 virus (RHDV2) caused sporadic cases of an European Brown Hare Syndrome-Like Disease in Italy and Spain. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 64, 1750–1761. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12562 (2017).

Asin, J. et al. Early circulation of rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus type 2 in domestic and wild lagomorphs in southern California, USA (2020–2021). Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 69, e394–e405. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.14315 (2022).

Hall, R. N. et al. Emerging rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus 2 (RHDVb), Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21, 2276–2278. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2112.151210 (2015).

Chehida, F. B. et al. Multiple introductions of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus Lagovirus europaeus/GI.2 in Africa. Biology (Basel) 10, 883. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10090883 (2021).

Gavier-Widen, D. & Morner, T. Epidemiology and diagnosis of the European brown hare syndrome in Scandinavian countries: A review. Rev. Sci. Tech. 10, 453–458. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.10.2.555 (1991).

Poli, A. et al. Acute hepatosis in the European Brown Hare (Lepus europaeus) in Italy. J. Wild. Dis. 27, 621–629. https://doi.org/10.7589/0090-3558-27.4.621 (1991).

Capucci, L., Fusi, P., Lavazza, A., Pacciarini, M. L. & Rossi, C. Detection and preliminary characterization of a new rabbit calicivirus related to rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus but nonpathogenic. J. Virol. 70, 8614–8623. https://doi.org/10.1128%2Fjvi.70.12.8614-8623.1996 (1996).

Le Gall-Recule, G. et al. Characterisation of a non-pathogenic and non-protective infectious rabbit lagovirus related to RHDV. Virology 410, 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.001 (2011).

Lemaitre, E., Zwingelstein, F., Marchandeau, S. & Le Gall-Reculé, G. First complete genome sequence of a European non-pathogenic rabbit calicivirus (Lagovirus GI.3). Arch. Virol. 163, 2921–2924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-018-3901-z (2018).

Strive, T., Wright, J. D. & Robinson, A. J. Identification and partial characterisation of a new Lagovirus in Australian wild rabbits. Virology 384, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.004 (2009).

Smertina, E. et al. First detection of benign rabbit caliciviruses in Chile. Viruses 16, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16030439 (2024).

Capucci, L., Nardin, A. & Lavazza, A. Seroconversion in an industrial unit of rabbits infected with a non-pathogenic rabbit haemorrhagic disease-like virus. Vet. Rec. 140, 647–650. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.140.25.647 (1997).

Rodák, J. L. et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of antibodies to rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus and determination of its major structural proteins. J. Gen. Virol. 71, 1075–1080. https://doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-71-5-1075 (1990).

Cavadini, P. et al., Identification of a new non-pathogenic lagovirus in Lepus europeaus. In 10th International Congress for Veterinary Virology, 9th Annual Epizone Meeting: “Changing Viruses in a Changing World”: August 31st-September 3rd, 2015, Montpellier, France. p 76–77. https://esvv2015.cirad.fr/content/download/4394/32241/version/1/file/ESVV+2015+full+proceedings-LAST.pdf

Cavadini, P. et al. Widespread occurrence of the non-pathogenic hare calicivirus (HaCV Lagovirus GII.2) in captive-reared and free-living wild hares in Europe. Transbound. Emerg. Dis 68, 509–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.13706 (2021).

Droillard, C. et al. First complete genome sequence of a hare calicivirus strain isolated from Lepus europaeus. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 7, e01224-e1318. https://doi.org/10.1128/mra.01224-18 (2018).

Droillard, C. et al. Genetic diversity and evolution of Hare Calicivirus (HaCV), a recently identified lagovirus from Lepus europaeus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 82, 104310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104310 (2020).

Mahar, J. E. et al. The discovery of three new hare lagoviruses reveals unexplored viral diversity in this genus. Virus Evol. 5, vez005. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vez005 (2019).

Mahar, J. E. et al. Benign rabbit caliciviruses exhibit evolutionary dynamics similar to those of their virulent relatives. J. Virol. 90, 9317–9329. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01212-16 (2016).

Strive, T., Wright, J., Kovaliski, J., Botti, G. & Capucci, L. The non-pathogenic Australian lagovirus RCV-A1 causes a prolonged infection and elicits partial cross-protection to rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus. Virology 398, 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.045 (2010).

Cooke, B. D. et al. Prior exposure to non-pathogenic calicivirus RCV-A1 reduces both infection rate and mortality from rabbit haemorrhagic disease in a population of wild rabbits in Australia. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 65, e470–e477. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12786 (2018).

Abrantes, J. et al. Recombination at the emergence of the pathogenic rabbit haemorrhagic disease virus Lagovirus europaeus/GI.2. Sci. Rep. 10, 14502–14504. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71303-4 (2020).

Lopes, A. M. et al. Full genomic analysis of new variant rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus revealed multiple recombination events. J. Gen. Virol. 96, 1309–1319. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.000070 (2015).

Cavadini, P., Trogu, T., Velarde, R., Lavazza, A. & Capucci, L. Recombination between non-structural and structural genes as a mechanism of selection in lagoviruses: The evolutionary dead-end of an RHDV2 isolated from European hare. Virus Res. 339, 199257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2023.199257 (2024).

Lopes, A. M. et al. Characterization of old RHDV strains by complete genome sequencing identifies a novel genetic group. Sci. Rep. 7, 13599–13602. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13902-2 (2017).

Liu, J., Kerr, P. J. & Strive, T. A sensitive and specific blocking ELISA for the detection of rabbit calicivirus RCV-A1 antibodies. Virol. J. 9, 182. https://doi.org/10.1186%2F1743-422X-9-182 (2012).

Capucci, L., Scicluna, M. T. & Lavazza, A. Diagnosis of viral haemorrhagic disease of rabbits and the European brown hare syndrome. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz. 10, 347–370. https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.10.2.561 (1991).

Cooke, B. D., Robinson, A. J., Merchant, J. C., Nardin, A. & Capucci, L. Use of ELISAs in field studies of rabbit haemorrhagic disease (RHD) in Australia. Epidemiol. Infect. 124, 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268899003994 (2000).

World Organisation for Animal Health. Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals. Section 3.7. Lagomorpha Chapter 3.7.2. Rabbit Haemorrhagic Disease Version adopted in May 2023, Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health; Last Access: 01/09/2023. https://www.woah.org/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/3.07.02_RHD.pdf

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy096 (2018).

Frohman, M. A., Dush, M. K. & Martin, G. R. Rapid production of full-length cDNAs from rare transcripts: Amplification using a single gene-specific oligonucleotide primer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 85, 8998–9002. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.85.23.8998 (1988).

Martin, D. P., Murrell, B., Golden, M., Khoosal, A. & Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 1, vev003. https://doi.org/10.1093/ve/vev003 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Silvia Brodini, Ms. Alessandra Previdi, and Cristina Palotta for their careful work in performing the ELISA tests and Ing. Marco Tironi for the figure artwork. They would also like to thank Dr Micaela Lenarduzzi, Dr. Gianni Perugini, Prof. Guido Grilli, Dr. Monica Cerioli, Dr. Anna Cerrone, Dr. Cristiana Tittarelli, Dr. Ruggero Brivio, and Dr. Sara Rota Nodari for their assistance with collecting blood samples.

Funding

This study was part of the Emergence of highly pathogenic Caliciviruses in Leporidae through species jumps involving reservoir host introduction (ECALEP) project, an ERA-Net ANIHWA (Animal Health and Welfare) Coordination Action funded under the European Commission’s ERA-Net scheme within the Seventh Framework Programme (Contract No. 291815). The ECALEP project was funded by the ANR (France, contracts ANR-14-ANWA-0004-01/04), the Research Council FORMAS (Sweden, contract FORMAS 221-2014-1841) and the Ministry of Health, Dep. for Veterinary Public Health, Nutrition & Food Safety (Italy) (CUPB85I13000160001). The study was also partly funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (MoH) IZSLER PRC2005/009 (CUPE87G06000120001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.C., A.L., and L.C. conceived the study, designed the experiments, and participated in organizing the field study. L.A. contributed to collecting samples and field data. L.C. performed the serological test. P.C., A.V., F.M., V.D.G., and B.B. performed the molecular work and the analyses. P.C. and A.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors critically read the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study that did not involve killing animals. The samples did not originate from experimental trials. Still, they took advantage of diagnostic activity conducted on found dead animals to ascertain the cause of death or as a control of the health status of regularly slaughtered rabbits for human meat consumption. Therefore, since the sampling was not specifically programmed as an experimental study but originating from diagnostic activity, we believed that it does not fall under the provisions of the National Law (e.g. DLSG 4/3 2014, n. 26. Application at the national level of the EU Directive 2010/63/UE) and no ethical approval or permit for animal experimentation was required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the name of Patrizia Cavadini, which was incorrectly given as Cavadini Patrizia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavadini, P., Vismarra, A., Merzoni, F. et al. Two decades of occurrence of non-pathogenic rabbit lagoviruses in Italy and their genomic characterization. Sci Rep 14, 29234 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79670-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79670-y