Abstract

To address the fatigue damage issues in continuous beam bridges under vehicle loads, a method using vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete to improve critical vulnerable areas of the bridge is proposed, thereby enhancing the bridge’s fatigue resistance. Fatigue performance and micro electron microscopy tests were designed for vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete, analyzing its damage conditions and microstructural changes under 0 to 2 million cyclic loads, and the key mechanical parameters of the concrete were determined. Based on this, a numerical analysis model was established to simulate the fatigue damage of continuous beam bridges under moving vehicle loads. The results show that piers made with vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete exhibit a 56.86% reduction in compressive damage compared to conventional piers, a reduction in stiffness damage range, and a 29.35% increase in fatigue life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In modern construction projects, concrete, as a key structural material, plays a critical role in the safety and durability of the building1. Particularly in bridges, high-rise buildings, and other structures subjected to heavy and dynamic loads, the mechanical properties and fatigue resistance of concrete are especially crucial. To enhance these properties of concrete, researchers and engineers have been exploring various innovative methods, among which the incorporation of steel fibers is an effective means of reinforcement. Zhao, Kaiyin2 suggested that the addition of steel fibers significantly enhances the compactness, freeze–thaw resistance, and dynamic compressive properties of IC. Zikai Xu et al.3 investigated the effects of steel slag and steel fibers on the mechanical properties, durability, and life cycle assessment of Ultra-High Performance Geopolymer Concrete (UHPGC). Hassan M et al.4 indicated that the incorporation of steel fibers has adverse effects on the fresh properties of Self-Compacting Concrete (SCC). The presence of steel fibers leads to enhanced mechanical properties, increased peak load and deflection at the point of failure, and additionally, increased crack mouth opening displacement. The presence of steel fibers also affects the fracture toughness of SCC mixtures. Dongming Huang et al.5 suggested that the addition of steel fibers helps offset the performance degradation caused by RCA, as fibers effectively bridge cracks and mitigate stress concentration risks. Danying Gao et al.6 found that the high-temperature stability of steel fibers significantly affects the residual compressive strength enhancement of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC). Yuliang Chen et al.7 investigated the mechanical properties of Steel Fiber Reinforced Recycled Aggregate Concrete (SFRRAC) under compressive-shear conditions. The study showed that as compressive stress increases, the failure characteristics of the specimens shift from brittle to ductile failure. Ji Shanshan et al.8 studied the impact splitting tensile properties and microstructural characteristics of Steel Fiber Reinforced Aggregate Concrete (SFRAC). The study indicates that steel fibers play a role in enhancing the dynamic splitting tensile strength and toughness, with an optimal fiber content around 1.0%. However, increasing the replacement rate of recycled aggregates can diminish the beneficial effects of steel fibers on mechanical properties. Cai Wu et al.9 proposed an empirical shrinkage model for steel fiber-reinforced recycled aggregate concrete under natural curing conditions.

However, ensuring the uniform dispersion of steel fibers within concrete to prevent clumping and maximize their reinforcing effects poses a technical challenge. Vibration mixing technology has emerged to address this issue. By applying vibration during the mixing process, it not only promotes adequate bonding between steel fibers and the concrete matrix but also significantly enhances the density and uniformity of the concrete. Zhang 10 investigated the mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete under vibration mixing and conventional mixing. Zheng11 examined the impact of vibration mixing on the fiber distribution and mechanical properties of Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC), with results indicating that vibration mixing can enhance the distribution coefficient of fibers and improve the mechanical properties of UHPC. Kaiyin Zhao et al.12 suggested that vibration mixing can increase the strength of Cementitious Slurry Matrix (CSM), reduce the strength coefficient of variation, and densify its microstructure. I. A. Volkov et al.13 found that during complex deformation processes, creep exhibits specific characteristics associated with the rotation of the principal stress, strain, and creep strain tensor. Zhao Wu14 demonstrated that compared to forced mixing, vibration mixing enhances both the compressive and splitting tensile strengths of concrete at different ages (3, 7, and 28 days), with the most significant improvement observed in the compressive strength of C50 reinforced concrete. Zhao, Kaiyin15 showed that the three-step mixing technique, compared to the traditional one-step method, can significantly reduce the plastic viscosity of concrete, enhance its fluidity, and markedly improve the compressive strength at 28 and 56 days. Zheng, Yuanxun16 suggested that vibration mixing can more effectively improve the distribution of steel reinforcement in concrete and increase the density of reinforced concrete, thereby significantly enhancing its mechanical properties. Zhang, C et al.17 compared the mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete produced by conventional and vibration mixing, with results indicating that concrete made with vibration mixing outperforms that made with conventional mixing in terms of mechanical properties. The mechanical properties of steel fiber concrete are linearly related to the matrix strength and the volume ratio of steel fibers, with optimal mechanical performance achieved when the volume ratio of steel fibers is less than 1%. Li H et al.18 investigated the thermal properties of hybrid fiber-reinforced reactive powder concrete (RPC) under high-temperature conditions, demonstrating that the addition of polypropylene and steel fibers at various volume fractions can enhance the thermal stability and crack resistance of RPC. Zhang, G et al.10 conducted experimental research on the impact of vibration mixing technology on the engineering properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete, proposing that vibration mixing can enhance the mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Hao, X et al.19 studied the thermal properties of steel fiber-reinforced reactive powder concrete (RPC) under elevated temperatures, with results indicating that steel fiber-reinforced RPC exhibits superior residual mechanical properties at high temperatures. Sanjeev, J20 evaluated the performance of steel and glass fiber-reinforced vibrated concrete and self-compacting concrete, concluding that steel fibers increase flexural strength and splitting tensile strength with minimal impact on compressive strength. Zemir, I et al.21 explored the potential of using steel fiber-reinforced self-compacting concrete (SFRSCC) to reinforce ordinary vibrated concrete (OVC), finding that the inclusion of steel fibers in self-compacting concrete significantly enhances its mechanical properties in both fresh and hardened states.

In summary, incorporating steel fibers into concrete is a key strategy for enhancing its performance and vibration mixing can significantly improve its mechanical properties. However, current research on vibration-mixed steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) primarily focuses on mechanical property testing lacks research on its fatigue performance while bridges, aqueducts, and high-rise buildings are frequently subjected to cyclic loads. Therefore, conducting fatigue performance tests on vibration-mixed SFRC and investigating its microstructure and macroscopic properties is imperative. This study presents the fatigue performance and microstructural analysis of steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) through vibration mixing and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) tests. It explores, for the first time, the fatigue characteristics of vibration-mixed SFRC, revealing its potential in engineering applications by simulating the fatigue damage of continuous beam bridges under moving vehicle loads. The aim is to propose new ideas for enhancing the safety of large structures such as bridges and culverts.

Experimental and numerical simulation

Fatigue performance test

Materials

The specimen dimensions selected for this study are 100 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm. Steel fiber contents of 1% and 2% were selected. The study investigates the effects of varying mixing methods and steel fiber volume fractions. The concrete trial mix has a strength grade of C50. OM is used to denote ordinary mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete, while VM denotes vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete. The test steel fibers are hook-ended, cut from wire, with a length of 35 mm, an equivalent diameter of 0.55 mm, a length-to-diameter ratio of 64, and a tensile strength of 1000 MPa. The cement used is PO 42.5 grade ordinary Portland cement. The coarse aggregate consists of hard granite, with a particle size ranging from 5 to 20 mm and a mud content of less than 1%. The fine aggregate is well-graded medium sand, with a fineness modulus of 2.66, a loose bulk density of 1514.5 kg/m3, and a bulk density of 2543 kg/m3. Class I fly ash is used.

The mix proportions of the concrete used in the experiment are shown in Table 1.

Fatigue performance test method

The purpose of this experiment is to ascertain the degradation of material parameters under traffic load. Initially, a simulation of the traffic load is conducted using software to determine the maximum and minimum stresses, which are then converted into fatigue loads based on the specimen size and equivalent stress.

(1) Loading frequency

As a brittle material, the fatigue analysis of concrete is minimally affected by loading frequency within a certain range, according to the research by Wu Zhimin et al14. A loading frequency that is too low can lead to excessive creep in concrete structures, adversely affecting the results. Conversely, a frequency that is too high can significantly reduce the fatigue life and strength of concrete. The fatigue test frequencies typically range from 2 to 8 Hz, and this experiment opts for a loading frequency of 6 Hz to balance cost-effectiveness with maintaining the fatigue strength and life of the concrete.

(2) Stress ratio

The stress ratio is correlated with the fatigue crack growth rate of the specimen. To prevent excessive inertial forces from causing an impact on the specimen during the application of cyclic loads, a stress ratio of 0.2 is utilized.

(3) Loading cycles

The experiment aims to obtain the degradation values of material parameters under traffic load by simulating the traffic load using software to ascertain the maximum and minimum stresses. These stresses are then converted into fatigue loads based on the specimen size and equivalent stress.

The specimens are subjected to loading cycles of 100,000, 500,000, 1,000,000, 1,500,000, and 2,000,000. After the two sets of specimens have been loaded, a universal testing machine is used to measure the compressive strength and modulus of elasticity for specimens prepared with different mixing methods.

Test equipment

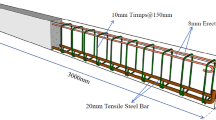

(1) Vibration mixing device

The experiment utilized a DT60ZBW twin-shaft vibrating mixer produced by Detong. This device primarily consists of a mixing drive mechanism, a vibration drive mechanism, and a chain transmission system. It measures 1900 mm × 1195 mm × 1620 mm, with a capacity of 60 L, a vibration power of 4 kW, and a mixing power of 2.2 kW. The vibrating mixing apparatus is depicted in Fig. 1. This mixer is capable of both vibrating and conventional mixing. For conventional mixing, only the forced mixing program needs to be initiated, whereas for vibrating mixing, both the forced mixing and the vibration programs must be activated simultaneously. Prior to mixing, the interior walls of the mixer must be thoroughly moistened with water to prevent the absorption of water in a dry state, ensuring the fluidity of the concrete and thus ensuring that the accuracy of the experimental data is unaffected.

During the concrete preparation for this experiment, meticulous control over the sequence of material addition and mixing duration was employed. Initially, coarse and fine aggregates, cement, and fly ash were manually introduced into the mixer according to a precisely calculated mix ratio for preliminary dry mixing. Subsequently, water and superplasticizer were incrementally added for further mixing. During the homogenization process, steel fibers were gradually incorporated to ensure an even distribution within the concrete. For conventional concrete mixing, dry mixing was performed for 1 min, followed by 1 min of mixing with a water and superplasticizer mixture while adding them, and concluded with 1 min of wet mixing. For steel fiber reinforced concrete, the process included 1 min of dry mixing, 1 min of mixing with the water and superplasticizer mixture, 1 min for evenly adding steel fibers, and finished with 1 min of wet mixing. Adjustments were made as necessary during the experiment.

(2) Fatigue testing rig

As depicted in Fig. 2. The fatigue testing system utilized in the experiment is a 250 kN axial fatigue testing machine, with the model number MTS 370.25. The testing machine has a maximum pressure capacity of 250 kN, a displacement range of 150 mm, and a control accuracy better than 1%.

During the test, the load was applied continuously and uniformly, with a loading rate of 0.5 MPa/s. For each set of specimens, three individual samples were tested, and the arithmetic mean of their strengths was taken as the strength indicator for that set. If any of the maximum or minimum values deviated from the median by more than 15% of the median in three measurements, the median was taken as the representative strength of that set; if both the maximum and minimum values deviated from the median by more than 15%, the results of that set were considered invalid.

Electron microscope test

Electron microscope test method

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted on specimens before fatigue testing to obtain the microstructural results of concrete under two mixing methods. Subsequently, observations were made on specimens subjected to 1 million and 1.5 million loading cycles. A comparison was made of the microstructures of steel fiber-reinforced concrete under the two mixing methods.

Electron microscope test set

As shown in Fig. 3, the experiment utilized an SBC-12 ion sputter coater and a KYKY-EM6200 scanning electron microscope (SEM). The instrument has a resolution of 4.5 nm at 30 kV, and the scanning electron microscope (SEM) offers magnification ranges from 15× to 250,000×, with a manually adjustable sample stage. In this experiment, test samples were observed at magnifications of 500× and 1000× and subsequently analyzed.

Project examples

Modeling and material ontology

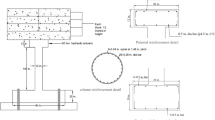

This study uses the Yangxin Expressway Yellow River Grand Bridge as the engineering context and focuses on a concrete continuous beam bridge with a main span of 120 m + 120 m + 120 m. A three-dimensional finite element model has been constructed, as shown in Fig. 4. The main beam features a single-box single-cell box-section, with a top slab width of 16.56 m, a bottom slab width of 8.5 m, and a top slab cantilever length of 4.03 m. The longitudinal reinforcement uses diameter Φ20mm rebar. Due to the bridge’s symmetry, the study only examines the results for Pier 1 (the left pier) and Pier 2 (the middle pier on the left span).

The model is constructed using solid elements, and to enhance computational efficiency, the rubber bearings are replaced with a spring-damper system in ABAQUS. The analysis type is set to implicit dynamic analysis, with the nonlinear option enabled and solved using asymmetric rectangular elements. The main bridge’s hollow structure uses the C3D8 element type, while the rest of the solid structure employs the C3D8R reduced integration element.

The damage plasticity model in ABAQUS is one of many constitutive models and plays a significant role in the analysis of structural damage performance. However, due to the need for material property parameter settings within this model, it is challenging to accurately obtain the mechanical properties of structural materials for numerical simulation analysis under actual test conditions. Therefore, this paper correlates the parameters required for the CDP model with the constitutive relationships provided by standards, discusses the definition and calculation of some important setting parameters, and verifies the parameters using the uniaxial tensile calibration method. Additionally, the model is applied to perform a finite element analysis on a simply supported concrete beam with bent-up reinforcement, and the results are compared with experimental outcomes to validate the accuracy of the parameters.

The material constitutive behavior is defined using ABAQUS’s built-in plastic damage model, Concrete Damaged Plasticity (CDP). The CDP model in ABAQUS is a continuous, plasticity-based concrete damage model, ABAQUS’s concrete plastic damage model is established based on the models by Lubliner 22 and Lee and Fenves 23, utilizing isotropic elastic damage and isotropic tensile and compressive plasticity theories to characterize the inelastic behavior of concrete 24..The CDP model assumes that tensile cracking and compressive crushing are the main causes of concrete cracking, while combining isotropic elastic damage, isotropic compressive, and tensile plasticity to describe the inelastic strain of concrete.

Zhao Boyu 25 suggests that the elastic strain energy produced by stress on damaged material is formally identical to that on undamaged material; it is only necessary to replace the stress with the equivalent stress or the elastic modulus with the equivalent elastic modulus at the time of damage. In the CDP model, the material initially behaves elastically, transitioning to the yield phase once a certain strength is reached. From the yield phase onwards, the material enters the damage phase, with each uniaxial compression or tension causing some degree of damage to the material.

The superstructure and deck of the bridge are constructed with C50 grade concrete and utilize the Concrete Damage Plasticity (CDP) model. Its Poisson’s ratio is 0.3. The bridge piers and bearing pads are constructed with steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) containing 1% steel fibers. and their constitutive model is based on the stress–strain relationships proposed by Lv Xilinn 26 and Zhang Ying 27. This model is combined with the fatigue performance test data from this study, which measured the compressive strength, elastic modulus, and mechanical properties of SFRC with two different mixing methods under 200,000 cycles of loading. These data are used to calculate the constitutive models of SFRC bridge piers with two different mixing methods under traffic loads.

(1) Stress–strain relationship of steel fiber concrete under compression:

In the equation, \({d}_{cf}\) represents the damage evolution parameter of steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) under uniaxial compression; \({f}_{cf,r}\) denotes the characteristic compressive strength of SFRC; \({\varepsilon }_{cf,r}\) represents the peak compressive strain of steel fiber-reinforced concrete corresponding to \({f}_{cf,r}\); \({\alpha }_{cf}\) is the shape parameter for the descending branch of the uniaxial compressive stress–strain curve of SFRC; \({V}_{f}\), \({l}_{f}\), \({d}_{f}\) are the volume fraction, length, and diameter of the steel fibers, respectively. \({\lambda }_{f}\) is the characteristic content of steel fibers.

(2) Stress–strain relationship of steel fiber concrete in tension:

In the equation, \({d}_{cf}\) is the damage evolution parameter for steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) under uniaxial tension; \({f}_{tf,r}\) is the characteristic tensile strength of SFRC; \({\varepsilon }_{tf,r}\) represents the peak tensile strain of steel fiber-reinforced concrete corresponding to \({f}_{tf,r}\); \({\alpha }_{tf}\) is the shape parameter for the descending branch of the uniaxial tensile stress–strain curve of SFRC.

(3) Calculation of damage factor:

In the equation, \(d\) is the damage factor of concrete, \(\sigma\) is the true stress of concrete, \(\varepsilon\) is the true strain of concrete, \({E}_{0}\) is the initial elastic modulus of concrete.

The damage factor ranges between 0 and 1, where 0 and 1 represent no damage and complete damage, respectively. However, there is no clear qualitative division for states in between. To better qualitatively process structural damage, we refer to the five-level damage classification proposed by HAZUS 9927,28,29,30,31,32 and the four-level damage condition division proposed by the Vision 33committee: Damage states are categorized based on the damage values of bridge bearings and piers. Tables 2, 3 and 4 shows the damage discrimination method.

Vehicle load loading

To simulate the dynamic load of moving vehicles, a subroutine named Dload was programmed, utilizing a user subroutine development platform to define the magnitude of the load, wheel trajectory, and vehicle speed. This study employs an implicit algorithmic system and has developed a subroutine file, which has been demonstrated to operate efficiently, ensuring a smooth computational process.

The parameter definitions primarily include the initial wheel position (Zini), vehicle speed (vel), vehicle load (pressure), and wheel width (dlen). In this simulation, the front and rear tires have different sizes, with the front tire contact area being 0.018 m2 and the rear tire contact area being 0.036 m2. The overall wheelbase of the vehicle is 3.815 m. The vehicle load advances to the next contact surface with each time step.

Results and evaluation

Fatigue strength decay of steel-fiber reinforced concrete

Initially, two sets of steel fiber-reinforced concrete with 1% fiber content but different mixing methods were subjected to fatigue loading at five different stress cycles: 100,000, 500,000, 1,000,000, 1,500,000, and 2,000,000 cycles. After the loading of each set was completed, a universal testing machine was used to measure the tensile strength, compressive strength, and elastic modulus of the specimens with different steel fiber contents. The failure modes of the compressive strength of steel fiber-reinforced concrete under two mixing methods after 100,000, 500,000, 1,000,000, and 1,500,000cycles of load are illustrated in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10.

As shown in Fig. 5a, after 100000 cycles of loading, there was spalling around the periphery of the conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete specimens. Due to the bonding effect of the steel fibers, the specimens did not disintegrate completely. Fig. 5b indicates that after 100000 cycles of loading, the VM specimens exhibited compressive strength damage patterns with minor spalling. A comparison between Fig. 5a and Fig. 5b reveals that, after 100000 cycles of loading, the OM specimens showed narrower fracture surfaces and less spalling compared to the VM specimens.

Figure 6a shows that after 500000cycles of loading, the OM specimens experienced significant spalling and their damage state was more dispersed compared to that after 100000 cycles, indicating a looser internal structure and reduced residual fatigue strength. Fig. 6b illustrates that the VM specimens exhibited compressive strength damage patterns after 500000cycles, with increased spalling and more severe damage compared to the 100000-cycle loading, as evidenced by a larger spalled area around the specimens. A comparison of Fig. 6a and b reveals that after 500000cycles of loading, the OM specimens had smaller volumes of disintegration and less spalling compared to the VM specimens.

Figure 7a demonstrates that after 1000000 cycles of loading, the OM specimens exhibited extensive spalling, with the damage state being more dispersed compared to that after 500000cycles. The increase in the number of cyclic loads led to a looser internal structure of the concrete and a reduction in residual fatigue strength. Figure 7b shows that after 1000000 cycles of loading, the VM specimens experienced significant spalling, with spalling observed all around the specimens. Compared to the 500000-cycle loading, the damage was more severe, and the spalled area increased. Comparing Fig. 7a and b, it can be concluded that after 1000000 cycles of loading, the OM specimens had smaller volumes of disintegration and less spalling compared to the VM specimens.

Figure 8a shows that after 1.5 million cycles of loading, the OM specimens exhibited extensive spalling around the perimeter, with the damage being more severe and more dispersed than after 1 million cycles. The increase in cyclic load count led to a looser internal structure of the concrete and a decrease in residual fatigue strength.

Figure 8b indicates that after 1.5 million cycles of loading, the VM specimens also showed extensive spalling around the perimeter, with more severe damage and an increased spalled area compared to the 1 million-cycle loading. Compared to the conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete under 1.5 million cycles of loading, the VM specimens had smaller disintegrated areas, less spalling, and no significant detachments were observed.

OM In summary, as the number of cycles increases, the residual fatigue strength of the specimens decreases. The VM specimens show less compressive strength damage and better performance in terms of spalling area and disintegration compared to the OM specimens.

The fatigue residual compressive strength and elastic modulus of steel fiber-reinforced concrete obtained from the two mixing methods tested are presented in Table 5.

Nonlinear fitting of the residual compressive strength and elastic modulus of steel fiber-reinforced concrete after different cyclic loads yields the fatigue degradation curves, as shown in Figs. 9 and Fig. 10.

Figure 9 illustrates that the fatigue degradation curve of compressive strength under the vibration mixing method descends gradually with increasing fatigue cycles, while a noticeable degradation in compressive strength occurs with the conventional mixing method between 1 and 1.5 million cycles. After 2 million cycles, the compressive strength of the OM method decreased by 14.39%, and the initial compressive strength of the VM method decreased by 9.67%.

Figure 10 shows that the fatigue degradation curves of the elastic modulus for both mixing methods have a similar downward trend, with an increased rate of decline between 1 and 2 million cycles for both. The initial elastic modulus of the OM method decreased by 24.15%, while that of the VM method decreased by 18.3%.

The experimental results indicate that the vibration mixing method provides better fiber uniformity and stronger bonding between the steel fibers and the concrete interface, resulting in improved integrity and durability of the concrete, with less reduction in compressive strength and elastic modulus after 2 million cycles.

The microstructure of steel-fiber-reinforced concrete

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was conducted on specimens after fatigue testing to observe the internal microstructure of two types of steel fiber-reinforced concrete subjected to different numbers of cyclic loads, comparing the changes in bond distribution between steel fibers and matrix materials within the concrete’s microstructure. To observe the internal structure of steel fiber-reinforced concrete at different stages of fatigue, SEM analysis was selected for specimens prepared using two mixing methods after 0, 1 million, and 1.5 million cycles of fatigue loading. Figures 11, 12 and 13 depict the microstructure of the matrix in steel fiber-reinforced concrete.

The microstructural observations presented in Fig. 11 reveal that, compared to conventional mixing, vibration mixing in steel fiber-reinforced concrete results in better compaction between the constituents, with no evident cracks, smaller and uniformly distributed pores, and superior performance. Additionally, the steel fibers are evenly dispersed throughout the matrix, preventing clumping and aggregation, which contributes to the enhancement of the concrete’s properties.

The microstructural observations depicted in Fig. 12 reveal the characteristics of the micro-interfaces in steel fiber-reinforced concrete after 1 million cyclic loads and their impact on material properties. In the conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete, it is observed that the steel fibers did not achieve uniform dispersion, with several fibers aggregating. This aggregation suggests that during the mixing and molding process, the steel fibers were not sufficiently dispersed nor fully encapsulated by the cement paste, which may lead to reduced bonding within the concrete and consequently affect its overall mechanical performance and durability.

In contrast, the steel fiber-reinforced concrete prepared with vibration mixing exhibits superior microstructural characteristics. Vibration mixing ensures a uniform distribution of steel fibers throughout the concrete matrix, with each fiber being tightly enveloped by the cement paste, resulting in a cohesive integrity with the matrix. This uniform distribution and encapsulation not only enhance the bonding strength between the steel fibers and the cement matrix but also significantly improve the density and overall performance of the concrete.

Furthermore, during the vibration mixing process, all components of the concrete, including both fine and coarse aggregates, achieve a highly uniform distribution. The complete encapsulation of both fine and coarse aggregates by the cement paste further strengthens the internal structure of the concrete, forming a dense and defect-free microstructure.

The microstructural observations revealed in Fig. 13 clearly demonstrate the differences in the microstructure of steel fiber-reinforced concrete after 1.5 million cyclic loads, which directly affect the material’s durability and structural integrity. In the conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete, numerous pores are present on the concrete surface, and larger voids are also observable. The presence of these voids, coupled with the formation of micro-cracks around them, indicates insufficient cohesion of the specimen, which may lead to a significant reduction in the bond between the concrete and steel fibers, thereby diminishing the material’s load-bearing capacity and durability.

In contrast, the steel fiber-reinforced concrete prepared with vibration mixing exhibits a denser internal structure. Although minor voids are also present in its internal structure after 1.5 million cyclic loads, their volume is significantly smaller than that in conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete specimens. Importantly, no micro-cracks were observed around the fracture surfaces of the vibration-mixed concrete, indicating a significant enhancement in its structural integrity and durability.

The advantage of vibration mixing lies in its ability to more effectively disperse steel fibers uniformly within the concrete matrix, ensuring that the cement paste fully envelops the aggregates and steel fibers, forming a tight bond. This uniform dispersion and encapsulation reduce the formation of pores and voids, thereby increasing the concrete’s density and crack resistance. Furthermore, vibration mixing also promotes a more uniform stress distribution, reducing crack propagation due to localized stress concentrations.

In summary, the application of vibration mixing technology results in a tighter microstructure and more uniform distribution of the mix in steel fiber-reinforced concrete, which plays a significant role in enhancing its compactness, mechanical properties, and service life.

Damage to piers of continuous beam bridges

Piers are the primary supporting structures of a bridge’s substructure, predominantly subjected to compressive stresses from the bridge deck transmitted through the bearings, and also to a portion of shear stress. By simulating the load-bearing conditions of piers under moving vehicle loads, the study investigates the damage conditions of steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers with different mixing methods, comparing the differences in damage values and extents between the two.

Figure 14 indicates that for the pier with conventional mixing, the compressive damage is primarily concentrated in the lower left corner, with a maximum damage value of 0.00007722. After employing vibration mixing, the compressive damage of Pier 1 is reduced to 0.00003331, achieving a damage reduction rate of 56.86%. A comparison between Fig. 14a and b reveals that the damage extent of vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers is significantly smaller than that of conventionally mixed piers.

Figure 15 shows that the maximum damage of Pier 2 with conventional mixing is 0.01174, and the compressive damage is reduced to 0.005365 with vibration mixing, achieving a damage reduction rate of 54.3%.

Figure 16 indicates that after one million cycles of fatigue loading, the compressive damage in Pier 1 shows that the maximum compressive damage of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers reaches 0.142, while for vibration-mixed piers, it is 0.109, demonstrating that the vibration mixing method can effectively reduce the degree of damage. The trend of damage values indicates that the damage increases over time, peaking between 20 and 25 s when the difference in damage values is at its maximum, and then stabilizes.

Upon further comparison between Pier 1 and Pier 2, the compressive damage values of Pier 2 are significantly higher than those of Pier 1, particularly at the top of the pier where it contacts the bearing. The damage of Pier 1 is primarily concentrated in the lower left corner, where the damage area of the vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers is significantly reduced compared to the conventional mixing method.

Analysis results from Figs. 14 and 15 indicate that the compressive damage area of Pier 2 has significantly expanded compared to Pier 1, a phenomenon observed in both conventionally mixed and vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers. However, vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers exhibit superior performance on Pier 2, with not only a reduced damage area but also a substantial decrease in damage values.

Plastic strain is an important indicator of concrete damage. Fig. 17 shows that under vehicle loads, the equivalent plastic strain at the pier bearing of vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete is significantly lower than that of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers. Comparing Fig. 16 and Fig. 17 reveals that the trends of the equivalent plastic strain curves and compressive damage curves for steel fiber-reinforced concrete piers with both mixing methods are consistent.

Damage to the bearing pads of continuous beam bridges

As shown in REF _Ref173506794 \h \* MERGEFORMAT Figs. 18a and REF _Ref173507041 \h \* MERGEFORMAT 19a, the compressive damage values of Bearing Pad 2 are identical to those of Bearing Pad 1, indicating that both types of steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads have reached their damage extremum at these locations. However, the compressive damage values for vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads are significantly lower than those for conventionally mixed bearing pads, regardless of whether they are Bearing Pad 1 or Bearing Pad 2.

Figure 18 indicates that the compressive damage of Bearing Pad 1 is primarily concentrated in the lower left corner, and the damage area of vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads is significantly smaller than that of conventionally mixed bearing pads. Fig. 18 and Fig. 19 show that the compressive damage area of Bearing Pad 2 is more pronounced compared to Bearing Pad 1. It is evident that the damage area of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads has expanded significantly compared to Bearing Pad 1, and vibration-mixed bearing pads exhibit a similar trend. In terms of the damage area of Bearing Pad 2, vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete outperforms conventionally mixed bearing pads, with a reduced damage area and a substantial decrease in damage values.

Figure 20a, b indicate that the stiffness damage of Bearing Pad 1 is primarily concentrated on the left side of the structure, and the stiffness damage area of vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads is significantly smaller than that of conventionally mixed bearing pads. Fig. 20 and Fig. 21 show that the stiffness damage area of Bearing Pad 2 is even more pronounced, with the stiffness damage area of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads having expanded significantly compared to Bearing Pad 1, and vibration-mixed bearing pads exhibit a similar trend.

Fig. 20 and Fig. 21 reveal that under vehicle loads, the maximum stiffness damage of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete for Bearing Pad 1 is 0.988, while for vibration-mixed Bearing Pad 1, the maximum compressive damage is 0.976. The maximum compressive damage for conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete Bearing Pad 2 is 0.988, and for vibration-mixed Bearing Pad 2, it is 0.983. The results indicate that some areas of the conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete for Bearing Pad 2 have reached the maximum stiffness damage. In terms of damage range for both Bearing Pad 1 and Bearing Pad 2, vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete performs better than conventionally mixed, with the stiffness damage range was reduced by 23.86%.

Figure 22 demonstrates that the fatigue life simulation analysis of steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads with two mixing methods reveals that the most critical fatigue life areas correspond with the previously mentioned areas prone to damage. The least favorable fatigue life of vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads is 4.02 million cycles, whereas for conventionally mixed pads, it is 2.84 million cycles, with a difference of 180,000 cycles, representing a 29.35% improvement in fatigue life for the vibration-mixed concrete.

Conclusion

This study conducted fatigue performance and electron microscopy tests on steel fiber-reinforced concrete with vibration mixing, and combined the constitutive model of the concrete with experimental data through numerical simulation to obtain models for two different mixing methods. Subsequently, the damage extremum and range of steel fiber-reinforced concrete bridge piers under vehicle loads were analyzed for both mixing methods. The conclusions are as follows:

(1) The fatigue degradation curves for compressive strength and elastic modulus of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete showed significant decay between 1 and 1.5 million load cycles, with the decay rate for compressive strength increasing from 2.77% to 12.89%, and that for elastic modulus from 3.57% to 13.28%. For vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete, these curves showed significant decay between 1.5 and 2 million cycles, with the decay rate for compressive strength increasing from 4.82% to 9.77%, and that for elastic modulus from 5.45% to 11.03%.

(2) After 1 and 1.5 million load cycles, the microstructure of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete showed non-uniform dispersion of steel fibers, with clusters observed. In contrast, vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete exhibited a dense internal structure with uniformly distributed fibers, which were entirely encapsulated by cement paste particles, forming a cohesive bond with the matrix.

(3) The use of vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete significantly reduced the maximum compressive damage and its extent in bridge piers. For conventional mixing, the maximum compressive damage of Pier 1 was concentrated in the lower left corner, with a maximum value of 0.00007722, which was reduced to 0.00003331 after vibration mixing, achieving a damage reduction of 56.86%. For Pier 2, the maximum damage was 0.01174 with conventional mixing, and it was reduced to 0.005365 with vibration mixing, resulting in a 54.3% damage reduction.

(4) The maximum stiffness damage values for both Bearing Pad 1 and Bearing Pad 2 of conventionally mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete were 0.988, while for vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete, the values were 0.976 for Bearing Pad 1 and 0.983 for Bearing Pad 2. This indicates that some areas of the conventionally mixed bearing pads have reached the maximum damage values. Vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete showed superior performance in reducing the stiffness damage range and values for both bearing pads.

(5) The least favorable fatigue life of vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete bearing pads was 3.02 million cycles, compared to 2.84 million cycles for conventionally mixed bearing pads, a difference of 180,000 cycles, representing a 6.4% improvement in fatigue life for the vibration-mixed concrete.

In summary, utilizing vibration-mixed steel fiber reinforced concrete (SFRC) in critical bridge components, such as piers and midspans, significantly enhances the bridge’s overall durability, extends its service life, and reduces maintenance costs. This conclusion can be extended to other infrastructures, including aqueducts and dams. Although this study addresses the damage to steel fiber-reinforced concrete (SFRC) bridge piers under vehicular loads, seismic loads are another significant factor affecting structural safety. Future research should explore the behavior of SFRC bridges under various seismic conditions.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

Michele, C.V. & Michele, D. Fatigue assessment and deterioration effects on Masonry elements: A review of numerical models and their application to a case study. Front. Built Environ. (2019).

Zhang, Y., Si, Z., Huang, L., Yang, C. & Du, X. Experimental study on the properties of internal cured concrete reinforced with steel fibre. Constr. Build. Mater. 393, 132046 (2023).

Xu, Z., Zhang, J., Zhang, J., Deng, Q., Xue, Z., Huang, G & Huang, X. Influence of steel slag and steel fiber on the mechanical properties, durability, and life cycle assessment of ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete. Construct. Build. Mater. 137590–137590 (2024).

Magbool, H.M. Experimental study on fracture properties of self-compacting concrete containing red mud waste and different steel fiber types. Key Eng. Mater. 73–80 (2024).

Huang, D., Lin, C., Liu, Z., Lu, Y. & Li, S. Compressive behaviors of steel fiber‐reinforced geopolymer recycled aggregate concrete‐filled GFRP tube columns. Structures 106829–106829 (2024).

Gao, D., Zhang, W., Tang, J. & Zhu, Z. Effect of steel fiber on the compressive performance and microstructure of ultra-high performance concrete at elevated temperatures. Construct. Build. Mater. 136830 (2024).

Chen, Y., He, Q., Jiang, R. & Ye, P. Mechanical properties of steel fiber reinforced recycled concrete under compression-shear stress state. J. Build. Eng. 109820 (2024).

Shanshan, J., Hua, Z., Xinyue, L., Xuechen, L, Yunhao, R., Sizhe, Z. & Zhenxing, C. Effect of steel fiber coupled with recycled aggregate concrete on splitting tensile strength and microstructure characteristics of concrete. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. (8) (2024).

Cai, W. et al. Experimental study of mechanical properties and theoretical models for recycled fine and coarse aggregate concrete with steel fibers. Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 12, 2933–2933 (2024).

Zhang, G., Hu, M., Jia, W., Liu, Z., Li, T., Yao, Y., & Liu, H. Experimental study on the influence of vibration mixing technology on engineering characteristics of steel fiber reinforced concrete. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. 719(2). 022081. (IOP Publishing, 2021).

Zheng, Y., Zhou, Y., Nie, F., Luo, H. & Huang, X. Effect of a novel vibration mixing on the fiber distribution and mechanical properties of ultra-high performance concrete. Sustainability 14(13), 7920 (2022).

Zhao, K., Zhao, L., Hou, J., Feng, Z. & Jiang, W. Impact of mixing methods and cement dosage on unconfined compressive strength of cement-stabilized macadam. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 16(1), 16 (2022).

Volkov, I. A., Igumnov, L. A., Kazakov, D. A., Shishulin, D. N. & Tarasov, I. S. State equations of unsteady creep under complex loading. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 59, 551–560 (2018).

Wu, Z. & Rongfang, W. Experimental study on the influence of high-frequency vibratory mixing on concrete performance. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 30(1), 20220199 (2023).

Zhao, K., Zhao, L., Liu, S., & Hou, J. Effect of three-step mixing technology based on vibratory mixing on properties of high-strength concrete. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 542(1). 012003. (IOP Publishing, 2019).

Zheng, Y., Wu, X., He, G., Shang, Q., Xu, J., & Sun, Y. Mechanical properties of steel fiber-reinforced concrete by vibratory mixing technology. Adv. Civ. Eng. (2018).

Zhang, C., Sun, Y., Xu, J. & Wang, B. The effect of vibration mixing on the mechanical properties of steel fiber concrete with different mix ratios. Materials 14(13), 3669 (2021).

Li, H., Hao, X., Qiao, Q., Zhang, B. & Li, H. Thermal properties of hybrid fiber-reinforced reactive powder concrete at high temperature. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 32(3), 04020022 (2020).

Li, H., Hao, X., Liu, Y. & Wang, Q. Thermal effects of steel-fibre-reinforced reactive powder concrete at elevated temperatures. Mag. Concr. Res. 73(3), 109–120 (2021).

Sanjeev, J. & Nitesh, K. S. Study on the effect of steel and glass fibers on fresh and hardened properties of vibrated concrete and self-compacting concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 27, 1559–1568 (2020).

Zemir, I., Debieb, F., Kenai, S., Ouldkhaoua, Y. & Irki, I. Strengthening of ordinary vibrated concrete using steel fibers self-compacting concrete. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 34(14), 1556–1571 (2020).

Lei, B., Qi, T., Li, Y. & Qin, S. An improved Lubliner strength model based on Ottosen failure criterion for concrete under multiaxial stress state. Struct. Concr. 23(5), 3199–3220 (2022).

Lee, J. & Fenves, G. L. Plastic-damage model for cyclic loading of concrete structures. J. Eng. Mech. 124(8), 892–900 (1998).

Zhang, T., Wu, L. & Noels, L. Damage-enhanced order reduction models for woven composites based on data-driven multiscale mechanics. 15ème Colloq. Natl. Calc. Struct. (2022).

Boyu, Z., Weiping, H. & Qingchun, M. Microscopic damage model considering the resolved normal stress on crystal slip plane. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 53(5), 1355–1366 (2021).

Xilin, Lv., Ying, Z. & Xucheng, N. Experimental study on axial compressive stress-strain curves of steel fiber high-strength concrete under monotonic and repetitive loading. J. Build. Struct. 38(01), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.14006/j.jzjgxb.2017.01.015.(inChinese) (2017).

Zhang, Y., Lv, X. & Nien, X. Experimental study on axial tensile stress-strain curve of steel fiber high-strength concrete. Struct. Eng.33(01), 107–113+200.https://doi.org/10.15935/j.cnki.jggcs.2017.01.015 (2017).

Rajat, D., Rahul, C. & Vishisht, B. Seismic risk mapping of bridges using HAZUS and ArcGIS: The case of Surat City, India. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Construct. (4) (2024)

Milyardi, R., Pribadi, K.S., Meilano, I. & Lim, E. Identifying the potential development of HAZUS model as an earthquake disaster loss model for school buildings in Indonesia. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science (1) (2023).

Shultz Steven, D. Accuracy of FEMA-Hazus single-family residential damage exposure data in Houston: Implications for using or correcting the Hazus General Building Stock. Nat. Hazards Rev. (4) (2021).

Eran, F., Amos, S., Jesse, R., Tsafrir, L., Ran, C., Veronic, A. & Doug, B. Tsunami loss assessment based on Hazus approach – The Bat Galim, Israel, case study. Eng. Geol. (prepublish), 106175 (2021).

Nan, D., Xiao, W. & Ying, Y. Indoor property flood damage assessment and insurance for residential buildings based on HAZUS—A case study of Mayangxi River Basin. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Vol. (1). 012158 (2021).

Ambhaikar, S.S., Patil, S.D. & Kognole, R.S. Performance based seismic analysis of buildings. J. Trend Sci. Res. Dev. (3), 249–255 (2018).

Funding

This article is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China project: “Seismic Response Analysis and Tuned Liquid Dampers (TLD) Mechanism of Multi-Chamber Trough Considering Two-Way Fluid-Solid Coupling” (Grant No. 52479137).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author Zhongyuan Xiao and Jianguo Xu: Researching and Writing a DissertationAuthor Jiangfei Wang and Qi Zhou: Provision and review of research directionsAuthor Lei Kou: Provision of relevant resourcesAuthor Jiandong Wei and Wanshuai Qi: wrote the main manuscript textAuthor Liang Huang: Collection and organization of data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, Z., Wang, J., Huang, L. et al. Research on the fatigue performance of continuous beam bridges with vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Sci Rep 14, 29927 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79739-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79739-8