Abstract

Post rotavirus vaccine introduction in Mozambique (September 2015), we documented a decline in rotavirus-associated diarrhoea and genotypes changes in our diarrhoeal surveillance spanning 2008–2021. This study aimed to perform whole-genome sequencing of rotavirus strains from 2009 to 2012 (pre-vaccine) and 2017–2018 (post-vaccine). Rotavirus strains previously detected by conventional PCR as G2P[4], G2P[6], G3P[4], G8P[4], G8P[6], and G9P[6] from children with moderate-to-severe and less-severe diarrhoea and without diarrhoea (healthy community controls) were sequenced using Illumina MiSeq® platform and analysed using bioinformatics tools. All these G and P-type combinations exhibited DS-1-like constellation in the rest of the genome segments as, I2-R2-C2-M2-A2-N2-T2-E2-H2. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that strains from children with and without diarrhoea clustered together with other Mozambican and global strains. Notably, the NSP4 gene of strains G3P[4] and G8P[4] in children with diarrhoea clustered with animal strains, such as bovine and caprine, with similarity identities ranging from 89.1 to 97.0% nucleotide and 89.5-97.0% amino acids. Our findings revealed genetic similarities among rotavirus strains from children with and without diarrhoea, as well as with animal strains, reinforcing the need of implementing studies with One Health approach in our setting, to elucidate the genetic diversity of this important pathogen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

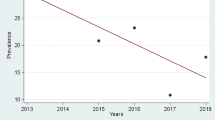

Group A rotavirus (RVA) persists as an important enteric pathogen associated with diarrhoea in children under five years of age1. Rotavirus vaccines were recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in countries with high disease burden in 20092, and Mozambique introduced the rotavirus vaccine (Rotarix® GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium) in September 20153, supported by data from the Global Enteric Multicenter study (GEMS) conducted in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, including Mozambique4. These data showed the contribution of rotavirus in diarrhoeal diseases, with an attributable fraction of 35.0% of moderate-to-severe diarrhoea (MSD), and 20.0% of less severe diarrhoea (LSD) in Mozambican infants4,5. The Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Manhiça (CISM) has been monitoring the impact of the vaccine through a passive surveillance3,6, which demonstrated a decrease in RVA-related cases, from 22.9 to 11.5% pre and post-vaccine introduction3. Despite the extensive documentation of the beneficial impact of rotavirus vaccination in sub-Saharan Africa7, rotavirus remains among the leading pathogens associated with diarrhoea in children under five years of age8.

RVA has a genome composed of 11 gene segments of a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), enclosed in a non-enveloped icosahedral triple-layered particle, consisting of outer, intermediate, and inner proteins9. These segments encode six structural proteins (VP1-VP4, VP6 and VP7) and five or six non-structural proteins (NSP1-NSP5/NSP6)9. The two major viral capsid proteins, VP7 (encoded by segment nine, G-type- glycoprotein G) and VP4 (encoded by segment four, P-type-protease sensitive P), form the basis for the conventional rotavirus binominal classification into G and P genotypes, widely used in RVA surveillance studies10. Due to the segmented genome, RVAs are prone to genome reassortments10. Whole genome characterization has been used to describe and trace the origin of the strains detected in humans and animals11. The most common and predominant human genotypes based on VP7 and VP4 characterization are G1, G2, G3, G4, G9 and G12 for VP7, and P[4], P[6] and P[8] for VP412. Whole genome classification identified three main genotype constellations: The prototype Wa-like (genotype 1), consisting of G1-P[8]-I1-R1-C1-M1-A1-N1-T1-E1-H110, the prototype DS-1-like (genotype 2), consisting of G2-P[4]-I2-R2-C2-M2-A2-N2-T2-E2-H210 and the minor prototype AU-1-like (genotype 3) consisting of G3-P[9]-I3-R3-C3-M3-A3-N3-T3-E3-H310. Some combinations, such as G1P[8], and G9P[8] have reported unusual DS-1-like constellations12,13. As of June 30, 2024, based on the nucleotide sequencing, 42G, 58P, 32I, 28R, 24 C, 23 M, 39 A, 28 N, 28T, 32E and 28 H genotypes have been identified14.

Previous studies conducted in various regions of Mozambique, including in Manhiça district, demonstrated that G1P[8], G2P[4], G12P[6], G12P[8] were more frequent in the country pre-vaccine introduction, with a switch to G3P[4] and G3P[8] post-vaccine introduction6,15,16,17. Additionally, studies conducted in Maputo, analysing human and animal strains revealed, through whole-genome sequencing (WGS), the circulation of the typical Wa-like G1-P[8]-I1-R1-C1-M1-A1-N1-T1-E1-H118, and DS-1-like G2/G8-P[4]-I2-R2-C2-M2-A2-N2-T2-E2-H2 constellations in humans19. While typical porcine constellation (G4P[6]/G9P[13]- I1/5-R1-C1-M1-A1/8-N1-T1/7-E1-H1)20 and artiodactyl bovine-like constellation consisting of G10P11-I2-R2-C2-M2-A3/A11/A13-N2-T6-E2-H3 have been found in animal strains21.

In Manhiça district, we characterized by WGS G3P[8] strains with typical Wa-like constellation, which was limited to rotavirus strains recovered from children with MSD22. Although, there is some available data regarding WGS of rotavirus in the country18,19,20,21,23, yet, there is still scarce data about characterization of different strains either Wa-like or DS-1 like constellations. Herein, we aimed to perform in-depth characterization of strains detected in children with (MSD and LSD) and without diarrhoea (healthy controls from the community) in Manhiça district, Southern Mozambique, through whole-genome sequencing, to obtain a more precise understanding of their genetic composition.

Results

Sequence analyses and full genome constellations

Rotavirus strains (n = 21) consisting of 11 pre and 10 post-vaccine introduction samples, from children under five years of age with MSD and LSD and without diarrhoea were sequenced. The Illumina MiSeq instrument registered an overall Phred quality score of Q ≥ 30 for all the sequence data. Full or near full length of the eleven gene segments, encoding VP1-VP4, VP6-VP7, and NSP1-NSP5/6 was determined for the 21 strains. All strains revealed to have a DS-1-like genotype constellation (Table 1). The open reading frames (ORFs) of the 11 gene segments of each of the 21 studied strains are summarized in Supplementary Table S1, and all ORFs were deposited in GenBank under accession numbers PP313617-PP313847.

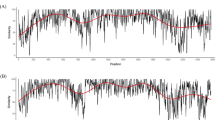

Phylogenetic and sequence analyses of VP7 encoding genome segment of G2, G3, G8 and G9

Phylogenetic analysis of G2 (pre-vaccine in children with MSD and a child without diarrhoea), G3 (post-vaccine in children with MSD and LSD), G8 (pre and post-vaccine in children with MSD and LSD) and G9 (post-vaccine in children with LSD) were based on previous described lineages24,25,26,27. In general, all segments were close to strains detected in other regions (Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas), with some particularities. G2 strains formed two clusters and were close to strains detected in Mozambique from 2011 to 2012 and were distant from two strains from 2013 (MOZ/0440/2013/G2P[4] and MOZ/0126/2013/G2P[4]), with an average of 96.0% nt and 96.1% aa identities (Fig. 1A and Supplementary, Table S2). Meanwhile, G3 were close to a human strain detected in Pakistan (PAK622/2016/G3P[8]) and a G3 strain detected in a bovine in India (RVA/Bovine_Bf212/COVASU/Parbhani/2017/G3P[X]), sharing 99.0% identity of nt and aa and were distant from previous G3 strains detected in the same period in MSD cases in Manhiça (MOZ/MAN-1811463.8/2021/G3P[8] and MOZ/MAN-1811450.8/2021/G3P[8]), with an average of 98.6% of nt and aa identities (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Table S3).

G8 were in two clusters close to strains detected in Mozambique in 2012, with identities of 99.9% of nt and 98.8% aa (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table S4). G9 clustered near strains detected in South Africa, one human (RVA/Human/ZAF/MRC-DPRU4677/2010/G9P[8]) strain sharing 98.2% for both nt and aa identities and G9 detected in two pigs (RVA/Pig-wt/ZAF/MRC-DPRU1540/2007/G6G9P[X] and RVA/Pig-wt/ZAF/MRC-DPRU1522/2007/G5G9P[X]) with an average of 98.9% identities of both nt and aa. This strain was distant from a strain detected in 2011 in Mozambique (RVA/Human-wt/MOZ/21162/2011/G9P[8]) with identities of 98.8% for both nt and aa (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Table S5).

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the ORF of the VP7 encoding gene segment, applying Tamura 3-parameter + gamma distributed (T92 + G) model: (A) G2 strains; (B) G3 strains. The study strains are indicated in red circles for MSD, black triangle for LSD and green square for children without diarrhoea. Roman numerals indicate lineages. Only bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown adjacent to each branch node. The Wa-like RVA strain from the USA was included as an out-group. Scale bars indicate the number of substitutions per nucleotide position.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the ORF of the VP7 encoding gene segment, applying Tamura 3-parameter + gamma distributed (T92 + G) model: (A) G8 strains; (B) G9 strain. The study strains are indicated in red circles for MSD, black triangle for LSD and green square for children without diarrhoea. Roman numerals indicate lineages. Only bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown adjacent to each branch node. The Wa-like RVA strain from the USA was included as an out-group. Scale bars indicate the number of substitutions per nucleotide position.

Phylogenetic and sequence analyses of the VP4 encoding genome segment of P4 and P6 strains

The phylogenetic trees of P[4] (from children with MSD and LSD and a child without diarrhoea) and P[6] (from children with MSD and LSD) were constructed based on previous described lineages25,28,29. Overall, they were close to strains detected in Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas, with some specificities. P[4] strains combined with G3 and G2 were in lineage III in the same cluster with a strain from Mozambique (RVA/Human/MOZ/044/2013/G2P[4]) sharing identities ranging from 98.3 to 98.7% nt and 98.3–98.8% aa. Different with P[4] combined with G8, which were in lineage II. They were close to Mozambican strains from 2012, with identities ranging from 97.5 to 100% nt and 97.6-100% aa. Additionally, these strains were closely related to a P[4] strain detected in a pig in South Africa (RVA/Pig-wt/ZAF/MRC-DPRU1533/2007/G2P[4]), with an average of 97.8% of nt and 97.9% of aa identities (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Table S6). P[6] strains were all close displaying 98.7% of both nt and aa identities. (Fig. 3B and Supplementary Table S7).

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree based on the ORF of the VP4 encoding gene segment. (A) P[4] genotype applying Tamura 3-parameter + invariable sites (T92 + I); (B) P[6] genotype applying Tamura 3-parameter + gamma distributed invariable sites (T92 + G + I) model. The study strains are indicated in red circles for MSD, black triangle for LSD and green squares for children without diarrhoea. Roman numerals indicate lineages. Only bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown adjacent to each branch node. The Wa-like RVA strain from the USA was included as an out-group. Scale bars indicate the number of substitutions per nucleotide position.

Phylogenetic and sequence analyses of VP1-VP3, and VP6 encoding genome segments

The phylogenetic analyses of the nucleotide sequences coding for VP1-VP3, and VP6 were constructed based on previous described lineages19,30,31. The studied strains clustered in lineage V in VP1 and VP6, lineage IV in VP2 and into two lineages in VP3 (V and VII). All the 21 study strains from MSD, LSD and strains from children without diarrhoea had the same topology in the trees. Notably, all G3P[4] strains (from children with MSD and LSD) clustered together. Meanwhile, G2P[4], G2P[6] and G8P[4] strains displayed a more dispersed pattern across VP1-VP3, trees; however, they formed distinct clusters in VP6, regardless of being from children with MSD or LSD, or strains from children without diarrhoea (Supplementary Figs. S1-4). In general, in each of these encoding genome segments (VP1-VP3 and VP6) the studied strains grouped into multiple clusters, alongside Mozambican (strains circulating between 2012 and 2013) and global strains, displaying identities ranging from 97.3 to 100.0% of both nt and aa (Supplementary Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S8–11). The VP1 cognate of G2P[6] strains from MSD were in the same cluster with a G8P[11] strain detected in a camel in Sudan (RVA/Camel-wt/SDN/MRC-DPRU/447/2002/G8P[11]), sharing 98.9% nt and aa identities (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Table S8).

Phylogenetic and sequence analyses of NSP1-NSP5/6 encoding genome segments

NSP1-NSP5/6 encoding genome segments were constructed using lineage framework previously described19,21,31,32. Phylogenetically, NSP1 and NSP2 trees of the 21 strains had similar topology, they formed two major clusters, one of G3P[4] (from children with MSD and LSD) and the other of G2P[6] (from a child with MSD) (Supplementary Figs. S5-6). Meanwhile, the topology of NSP3 and NSP5/6 were also similar, NSP3 formed two major closely related clusters, one composed of G3P[4] (from children with MSD and LSD) and the other encompassing G2P[4] (from children with MSD and children without diarrhoea) and G2P[6] (MSD) strains. These clusters shared both nt and aa identities ranging from 96.0 to 96.6% (Supplementary Figs. S7, 9 and Tables S14, 16). Conversely, NSP5/6 featured one cluster of G3P[4] (from children with MSD and LSD) closely related to a human strain from Thailand (THA/DBM2018-105/2018/G2P[4]), sharing an average 99.0% of both nt and aa identities, and a human strain from Pakistan (PAK663/2016/G3P[4]), with an average 99.8% of both nt and aa identities (Supplementary Tables S16). The other NSP5/6 cluster was from G2P[4] (from children with MSD and a strain from children without diarrhoea), G8P[4] (from children with LSD) and G2P[6] (from children with MSD) and was close to a strain from Italy (RVA/Human-wt/ITA/PG01/2011/G2P[4]) sharing an average 96.5% of nt and 98.8% of aa identities (Supplementary Figs. S9 and Table S16).

The NSP4 cognate of G8P[4] (MSD and LSD) were in a cluster with bovine strains from Mozambique (RVA/Cow-wt/MOZ/MPT-93/2016/G10P[11] and RVA/Cow-wt/MOZ/MPT-307/2016/G10P[11]) with an average 89.1% nt and 89.5% aa identities. They also displayed close similarity to a caprine strain from Bangladesh (RVA/Caprine/BD/GO34/1999/NSP4), with an average 93.0% nt and 93.2% aa identities and a bovine strain from India (RVA/Bovine/IND/IC15/IVRI/2012/NSP4) with an average 93.6% nt and 93.8% aa identities (Supplementary Fig. S8 and Table S15). Additionally, NSP4 cognate of G3P[4] (from children with MSD and LSD) was in the same cluster with a bovine strain from India (RVA/Bovine/IND/IC15/IVRI/2012/NSP4), with an average 97% of both nt and aa identities and close to a caprine strain from Bangladesh (RVA/Caprine/BD/GO34/1999/NSP4) with an average 92.3% nt and 92.6% aa identities (Supplementary Fig. S8 and Table S15).

Comparative amino acid analysis between P4 strains combined with G2, G3 and G8

The deduced amino acid sequences of P[4] strains were compared using the DS-1-like strain from the USA (RVA/Human-tc/USA/DS-1/1976/G2P[4]) as a reference strain. Notably, they exhibited aa exclusive differences in 10 positions. Furthermore, the examination of the VP4 epitope sites unveiled marked disparities across all the P[4] strain. The highest aa differences were observed within P[4] combined with G8, with 21 different residues from the other P[4]’s, examples of changes include D150E; R172K; S187R; N189D; S279N; S305L and S603L; V311I; G651R; N684S; I630M. Meanwhile, three aa residues were exclusively different in P[4] strains combined with G2 (V35, V130, G162), while only two aa were different in P[4] strains combined with G3 (K136T, V607I) (Supplementary Table S17). All the P[4] study strains did preserve the arginine (R) cleavage sites at residues 230, 240 and 246. Additionally, they preserved the proline (P) residues at positions 68, 71, 224 and 225 in the conserved region (Supplementary Table S17).

Comparative amino acid analysis of NSP4

The amino acid sequences within the NSP4 encoding genome segment of the studied strains were compared with the animal strains with which they clustered with in the phylogenetic trees, using the prototype DS-1 like from the USA (RVA/Human-tc/USA/DS-1/1976/G2P[4]) as reference strain. Several noteworthy aa differences emerged across distinct antigenic regions in some strains, namely in the antigenic region IV: differences at positions L16S, M17R, and S19R; antigenic region III: differences at positions K115N, Y131H, and K133R; antigenic region II: changes spanning positions V136I to I142V. Region I also revealed amino acid differences at positions R154K, E157K, E160K, N161S, and K163R (Supplementary Table S18). Within the enterotoxin domain (aa 114–135), we detected a few aa changes, specifically, G3P[4] strains (MSD and LSD) displayed a change from K115N. Additionally, in G8P[4] and G8P[6] strains, both from LSD, there was a mutation at position Y131H. Additionally, all strains from G2P[4], G2P[6], and G8P[4] from pre-vaccine in children with MSD and LSD, and children without diarrhoea exhibited a common aa difference at position M135V. This same change was also observed in G8P[6] and G9P[6] strains from children with LSD post-vaccine introduction (Supplementary Table S18).

Discussion

This is one of the few studies characterizing rotavirus strains by WGS in Mozambique. We demonstrated that all strains analysed exhibited a DS-1-like constellation, collectively. Whole-genome data regarding the characterization of Mozambican DS-1-like rotavirus strains are limited, especially among children with LSD and children without diarrhoea. Many surveillance studies identify rotavirus genotypes through RT-PCR33. Available data of whole-genome rotavirus DS-1-like strains in Mozambique are limited to G2P[4] and G8P[4] detected in children with MSD19. The phylogenetic analysis of each of the 11 genome segments of the studied strains (from children with MSD, LSD and children without diarrhoea), suggested that they were genetically similar to each other, as they clustered together. The fact that these strains are similar may indicate the host factors as the main determinant of whether they develop more or less severe symptoms after infection. Therefore, additional studies are needed to evaluate these host factors, such as malnutrition, which has been described to predispose infants to enteric infections34.

Meanwhile, the study strains were similar to other strains detected in Mozambique, other African (Zimbabwe, Zambia, Kenya, South Africa, Ghana, Malawi, Senegal, Gabon, Cameroon and Congo), European (Italy), Asian (Japan, India, Thailand, Pakistan, Philippines), Oceania (Australia) and North American (USA) countries in all the 11 genome segments, suggesting transmission within various regions. Notably, in the phylogenetic tree of the NSP4 encoding genome segment some study strains were clustering with animal strains detected in Mozambique and other countries (Bangladesh and India). The NSP4 is known to have a higher evolutionary rate and has the potential to reassort more frequently in nature than other genome segments35,36, such as demonstrated by the analysis of G2P[4] from Belgium detected after vaccine introduction36 and a DS-1-like G8P[8] strain detected in Thailand37.

It is also worth noting that genome segments of some strains from children with and without diarrhoea, were close strains known to circulate in humans, but were detected in animals, such as P[4] in a pig, G3 in a bovine, and G8P[11] in a camel. Previous work in Manhiça revealed possible reassortment events between various segments (VP7, VP6, VP1, NSP3, and NSP4) of Wa-like G3P[8] strains from MSD cases, closely related with porcine, bovine, and equine strains22. The pattern observed with our strains in general, may in part support the hypothesis that rather than whole genomes being transferred from other species to humans there is frequent exchange of genome segments38 and this occurrence is mainly observed in rural areas39, such as our study setting3.

As the P[4] strains clustered in two separate lineages, G2P[4] and G3P[4] in lineage III and G8P[4] in lineage II, their amino acid sequences were examined to determine their differences. The analysis showed some amino acid differences between them, including differences in the antigenic regions of the VP4 outer capsid protein, which are critical for inducing neutralizing antibodies40. Many of the amino acid substitutions are not believed to be associated with changes in protein functions, such as a change from valine to isoleucine or isoleucine to methionine, which are non-reactive and rarely directly involved in protein function41, and Asparagine to aspartic acid which are both involved in protein active or binding sites41. Although, other are believed to be associated with changes, example is the change from Arginine, which is a polar amino acid located in protein active or binding sites, to glycine may probably reduce the cholangiocyte binding and infectivity41. This has been demonstrated in a mutant of rotavirus VP4 which had an R446G change generated by a reverse genetics system42. These findings may allow speculating that the changes observed in residue G162 of P[4] combined with G2 from a strain isolated from children without diarrhoea may have resulted in the reduction of virus infectivity as described above42. All P[4] from the studied strains, conserved the potential VP4 arginine cleavage sites (positions 230, 240, and 246), similar to most rotavirus strains. These sites are responsible for assuring the virus infectivity43. The proline residues which are known to cause three-dimensional structural distortion and may influence the conformation of the VP4 protein43 were also conserved in the studied strains (positions 68, 71, 224, 225).

Analysis of consensus NSP4 amino acid sequences of the studied strains, from residues 1 to 175 showed several amino acid substitutions at the previously described antigenic site II (ASII:136–150)44, with a change observed in position V136I in two strains from children without diarrheoa and one MSD strain pre-vaccine introduction. This position is reported within the region described to alter pathogenesis mediated by the NSP4 protein45. The substitution of amino acids within the antigenic sites may be assumed to have an evolutionary impact46. Changes in the sequences of NSP4 together with the structural proteins VP4 and VP7 are reported to be associated with asymptomatic infections in humans47, even though the amino acid variation in NSP4 has not always been associated with asymptomatic infections48. On the other hand, some amino acid substitutions were observed in the enterotoxin domain (positions 114–135) of the studied strains. As NSP4 is associated with rotavirus pathogenesis and it has an enterotoxin-like activity, which induces an intracellular calcium imbalance, resulting in membrane instability and diarrhoea, which has been shown in experiments with mice49, the observed substitutions in some studied strains within this region, may suggest somehow to affect the toxigenic activity or conformation of the NSP4 protein or may even be associated with changes in rotavirus virulence45.

One of the limitations of this study is the reduced number of strains from children without diarrhoea that were analysed (three), and all were isolated pre-vaccine introduction. Additionally, few similar strains were observed in both periods, limiting the comparison of strains pre- and post-vaccine introduction. Although there is evidence of possible occurrence of reassortment events in the Manhiça district, was not possible to perform reassortment, because strains with the NSP4 segment close to animal strains do not have similar VP7 and VP4 genome segments. Additionally, a comprehensive protein-protein interaction analysis or modelling is required to evaluate a potential impact in protein function. For example, the pathogenesis mediated by NSP4 has been previously described to be more likely associated with the conformation of the carboxyl region of the toxigenic region, rather than with the presence of a specific amino acid45.

We may conclude that rotavirus strains from children with and without diarrhoea in children under five years of age were genetically similar among the respective genotypes and we had strains with a segment with some similarities with animal strains, suggesting possible reassortment events in our setting. Moreover, the aa substitutions observed in non-antigenic regions of P[4] strains may have led them to cluster in different lineages, according to their combination with a specific VP7 genotype. The aa change from arginine to glycine within the enterotoxin domain of NSP4 of the strains from children without diarrhoea and from arginine to glycine in the aa sequence of VP4 of one strain from MSD, suggests the change in the infectivity and pathogenesis of the strains, although further analyses are required. These results highlight the importance of continuous whole-genome surveillance to evaluate the non-antigenic regions in RVA infectivity and evolution. In addition, the results reinforce the need to implement studies to assess host factors that may predispose to symptomatic or asymptomatic infection, and to implement surveillance using the ‘One Health’ approach to assess the interaction of human and animal rotavirus strains and the impact of the vaccine on circulating and emerging strains.

Methodology

Sample source and site description

This study analysed 21 stool samples from children under the age of five years with (MSD and LSD) and without (health controls from community) diarrhoea. The samples were collected as part of the GEMS study conducted pre rotavirus vaccine introduction (2007–2012) and the surveillance of rotavirus conducted post-vaccine introduction (2015–2019), according to the relevant guidelines and regulations4. MSD were cases with criteria for hospitalization, and LSD cases attended during the outpatient visits, as previously described5,6,50. Samples from eleven children (6 girls and 5 boys) were collected pre-vaccine introduction and ten children (7 girls and 3 boys) post-vaccine introduction. Five of the children enrolled post-vaccine introduction were fully vaccinated, two had received only one dose and three were not vaccinated.

This study included samples that had been genotyped in our previous study6, using conventional reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)51. Their percentages were as follows: G2P[4], 6% (in children with MSD) and 3% (in children without diarrhoea) pre-vaccine introduction; G2P[6], 8% (in children with MSD) pre-vaccine, G3P[4], 10% (in children with MSD) and 20% (in children with LSD) post-vaccine introduction6. Additionally, samples genotyped later, were included in the study, such as G8P[4], G8P[6], and G9P[6]. These genotypes were also selected by the fact that they had sufficient RNA quantity for WGS. The description of the number of strains for each case and period (pre-and post-vaccine introduction) was presented in the Supplementary Table S19. GEMS and the rotavirus surveillance were carried out by CISM, which has been running the morbidity (implemented in the Manhiça District Hospital and other peripheral heath facilities) and the demographic surveillances, covering the entire District. The Manhiça district and the surveillance platforms’ characteristics have been described previously52.

Laboratory procedures

Double stranded RNA (dsRNA) extraction and purification

The dsRNA extraction in stool samples was performed using TRIzol™ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following a previously described protocol53, including some modifications and purification steps, as previously detailed22. Briefly, a tube containing a suspension of 500 mg of stool in 1 mL of TRIzol was incubated at room temperature for 5 min and centrifuged at 16,000 xg for 15 min at 4 °C (similar conditions applied in the following steps). Afterward, 300 µL of chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO, United States) were added to the solution and centrifuged. The supernatant was passed on to a new tube and 650 µL of isopropanol (Sigma-Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO, United States) added, followed by centrifugation, removal of the supernatant and drying of the pellet in the tubes. About 95 µL of elution buffer – EB (MinElute Gel extraction kit-Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) were added to the tubes to re-suspend the pellet. Subsequently, 30 µL of 8 M lithium chloride (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the RNA, incubated for precipitation at 4 °C overnight, to allow the complete removal of single stranded RNA (ssRNA) and inhibitors of cDNA synthesis54. Following incubation, the solution was centrifuged at 16,000 xg at 4 °C for 30 min and the supernatant purified, using the MinElute gel extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufactures’ protocol. To evaluate the integrity of all the extracted RNAs, approximately 5 µL was loaded onto 1.0% agarose gel, along with 100 bp molecular-sized ladder, stained with 0.5 µg/mL ethidium bromide and visualized in the gel-documentation system, under ultraviolet light (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, United States).

cDNA synthesis, DNA library preparation and whole genome sequencing

The dsRNA was sequenced at the University of the Free State - Next Generation Sequencing (UFS-NGS) Unit, South Africa. First, all the extracted dsRNA was synthesized to complementary DNA (cDNA) using the Maxima H Minus Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA), as described by the manufacturer. Briefly, 13 µL of the dsRNA were denatured at 95 °C for 5 min, and 1 µL of 100 µM of random hexamer primer added to the tube, followed by an incubation in a thermocycler at 65 °C. Afterward, 5 µL of the First Strand Reaction Mix and 1 µL of the First Strand Enzyme Mix were added to the tubes and incubated at 25 °C for 10 min, with subsequent incubation of 2 h at 50 °C and reaction termination through heating at 85 °C for 5 min. Fifty five microliters of nuclease-free water were added to the tubes, with 20 µL of 5X Second Strand Reaction Mix, and 5 µL of Second Strand Reaction Enzyme Mix followed by incubation at 16 °C for 60 min. Six microliters of 0.5 M EDTA and 10 µL of RNAse were added to stop the reaction and the cDNA was incubated at room temperature for 5 min, followed by purification using the MSB® Spin PCRapace Purification Kit (Stratec Molecular, Berlin, Germany). Afterwards, the DNA libraries were prepared using the Nextera® XT DNA Library Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, California, US), as previously described12,22 and the sequencing was performed using the Illumina MiSeq® sequencer (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA), as previously described12,22.

Data analysis

Genome assembly and generation of whole genome constellations

All the sequence reads generated from the Illumina® MiSeq platform in FASTQ format were trimmed to remove low quality and short reads using Geneious Prime® (v.2022.0.1) software. The ‘per base sequence quality plot’ module was assessed to consider data files with a distribution of Q30 quality score for subsequent analysis. Afterwards, a de novo assembly, to get a complete genome and reference mapping of the reads to assign to a specific location in the genome55, was performed using the prototype DS-1-like G2P[4] reference strain, RVA/Human-tc/USA/DS-1/ 1976 /G2P[4] (accession numbers HQ650116-HQ650126) using CLC Bio Genomics Workbench (v.22.0, Qiagen) software56 and Geneious Prime® (v.2022.0.1) software57, respectively. The curated assembled and mapped sequences were used to derive consensus for respective genome segments of each strain using Geneious Prime® (v.2022.0.1)57. The genotype of each genome segment was determined using the Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR) tool (accessed on 15th December 2022)58. FASTA files with nucleotide sequences of a given rotavirus genome segment were submitted and compared to a reference database of known rotavirus sequences. A combination of nucleotide alignments and genotype-specific cut-off values was used to assign the genotype of the input sequence.

Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

The study sequences and additional representative sequences from different lineages of RVA downloaded from GenBank were included in the dataset for comparisons. Each dataset with a specific gene segment was aligned using the Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log Expectation (MUSCLE) algorithm. For the phylogenetic analysis of each genome segment, the evolutionary model that best fitted the data was determined based on the Corrected Akaike Information Criteria (AICc), and the trees constructed using the Maximum-Likelihood method inferred for each segment and applying a bootstrap method with 1,000 replicates to assess the tree robustness59. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% were considered consistent. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence identities were estimated using the pairwise distance matrices and the p-distance algorithm. All the phylogenetic analysis was performed using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA), version 1159.

Data availability

All the sequences characterized in this study were deposited at GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under the accession numbers PP313617-PP313847.

References

Troeger, C. E. et al. Quantifying risks and interventions that have affected the burden of diarrhoea among children younger than 5 years: an analysis of the global burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30401-3 (2019).

Mwenda, J. M., Parashar, U. D., Cohen, A. L. & Tate, J. E. Impact of rotavirus vaccines in sub-saharan African countries. Vaccine. 36, 7119–7123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.026 (2018).

Manjate, F. et al. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrheal hospitalizations in children younger than 5 years of age in a rural southern Mozambique. Vaccine. 40, 6422–6430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.09.050 (2022).

Kotloff, K. L. et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 382, 209–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60844-2 (2013).

Kotloff, K. L. et al. The incidence, aetiology, and adverse clinical consequences of less severe diarrhoeal episodes among infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: a 12-month case-control study as a follow-on to the global enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). Lancet Glob Health. 7, e568–e584. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30076-2 (2019).

Manjate, F. et al. Molecular epidemiology of Rotavirus strains in symptomatic and Asymptomatic Children in Manhiça District, Southern Mozambique 2008–2019. Viruses. 14, 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14010134 (2022).

Mwenda, J. M. et al. Impact of Rotavirus Vaccine introduction on Rotavirus hospitalizations among Children under 5 years of age—World Health Organization African Region, 2008–2018. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, 1605–1608. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab520 (2021).

Buchwald, A. G. et al. Etiology, presentation, and risk factors for diarrheal syndromes in 3 sub-saharan African Countries after the introduction of Rotavirus vaccines from the Vaccine Impact on Diarrhea in Africa (VIDA) Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, S12–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad022 (2023).

Asensio-Cob, D., Rodríguez, J. M. & Luque, D. Rotavirus particle disassembly and assembly in vivo. Vitro Viruses. 15, 1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15081750 (2023).

Uprety, T., Wang, D. & Li, F. Recent advances in rotavirus reverse genetics and its utilization in basic research and vaccine development. Arch. Virol. 166, 2369–2386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-021-05142-7 (2021).

Kunić, V. et al. Interspecies transmission of porcine-originated G4P[6] rotavirus A between pigs and humans: a synchronized spatiotemporal approach. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1194764. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1194764 (2023).

Mwangi, P. N. et al. Uncovering the First Atypical DS-1-like G1P[8] Rotavirus strains that circulated during Pre-rotavirus Vaccine introduction era in South Africa. Pathogens. 9, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9050391 (2020).

Fukuda, S. et al. Full genome characterization of novel DS-1-like G9P[8] rotavirus strains that have emerged in Thailand. PLoS ONE. 15, e0231099. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231099 (2020).

Rotavirus Classification Working Group. RCWG n.d. Available online: accessed June 30, (2024). https://rega.kuleuven.be/cev/viralmetagenomics/virus-classification/rcwg.

Langa, J. S. et al. Epidemiology of rotavirus A diarrhea in Chókwè, Southern Mozambique, from February to September, 2011: Epidemiology of Group A Rotavirus Diarrhea in Southern Mozambique. J. Med. Virol. 88, 1751–1758. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24531 (2016).

João, E. D. et al. Molecular epidemiology of Rotavirus a strains pre- and post-vaccine (Rotarix®) introduction in Mozambique, 2012–2019: emergence of genotypes G3P[4] and G3P[8]. Pathogens. 9, 671. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9090671 (2020).

João, E. D. et al. Rotavirus a strains obtained from children with acute gastroenteritis in Mozambique, 2012–2013: G and P genotypes and phylogenetic analysis of VP7 and partial VP4 genes. Arch. Virol. 163, 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3575-y (2018).

Munlela, B. et al. Whole genome characterization and evolutionary analysis of G1P[8] Rotavirus a strains during the pre- and Post-vaccine periods in Mozambique (2012–2017). Pathogens. 9, 1026. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9121026 (2020).

Strydom, A. et al. Whole genome analyses of DS-1-like Rotavirus A strains detected in children with acute diarrhoea in southern Mozambique suggest several reassortment events. Infect. Genet. Evol. 69, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2019.01.011 (2019).

Boene, S. S. et al. Prevalence and genome characterization of porcine rotavirus A in southern Mozambique. Infect. Genet. Evol. 87, 104637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104637 (2021).

Strydom, A. et al. Genetic characterisation of South African and Mozambican bovine rotaviruses reveals a typical bovine-like Artiodactyl Constellation derived through multiple reassortment events. Pathogens. 10, 1308. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10101308 (2021).

Manjate, F. et al. Genomic characterization of the rotavirus G3P[8] strain in vaccinated children, reveals possible reassortment events between human and animal strains in Manhiça District, Mozambique. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1193094. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1193094 (2023).

Munlela, B. et al. Whole-genome characterization of Rotavirus G9P[6] and G9P[4] strains that emerged after Rotavirus Vaccine introduction in Mozambique. Viruses. 16, 1140. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16071140 (2024).

Le, L. K. T. et al. Genetic diversity of G9, G3, G8 and G1 rotavirus group a strains circulating among children with acute gastroenteritis in Vietnam from 2016 to 2021. Infect. Genet. Evol. 118, 105566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2024.105566 (2024).

Agbemabiese, C. A. et al. Genomic constellation and evolution of Ghanaian G2P[4] rotavirus strains from a global perspective. Infect. Genet. Evol. 45, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2016.08.024 (2016).

Medeiros, R. S. et al. Genomic Constellation of Human Rotavirus G8 strains in Brazil over a 13-Year period: detection of the novel bovine-like G8P[8] strains with the DS-1-like backbone. Viruses. 15, 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15030664 (2023).

Sadiq, A., Bostan, N., Bokhari, H., Yinda, K. C. & Matthijnssens, J. Whole Genome Analysis of Selected Human Group A Rotavirus strains revealed evolution of DS-1-Like single- and double-gene reassortant rotavirus strains in Pakistan during 2015–2016. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02641 (2019).

Mwangi, P. N. et al. The evolution of Post-vaccine G8P[4] Group a Rotavirus Strains in Rwanda; notable variance at the neutralization Epitope sites. Pathogens. 12, 658. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens12050658 (2023).

Mokoena, F. et al. Whole genome analysis of African G12P[6] and G12P[8] Rotaviruses provides evidence of porcine-human reassortment at NSP2, NSP3, and NSP4. Front. Microbiol. 11, 604444. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.604444 (2020).

Doan, Y. H., Nakagomi, T., Agbemabiese, C. A. & Nakagomi, O. Changes in the distribution of lineage constellations of G2P[4] Rotavirus a strains detected in Japan over 32 years (1980–2011). Infect. Genet. Evol. 34, 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2015.05.026 (2015).

Agbemabiese, C. A. et al. Sub-genotype phylogeny of the non-G, non-P genes of genotype 2 Rotavirus A strains. PLoS One. 14, e0217422. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217422 (2019).

Doan, Y. H. et al. Emergence of Intergenogroup Reassortant G9P[4] strains following Rotavirus Vaccine introduction in Ghana. Viruses. 15, 2453. https://doi.org/10.3390/v15122453 (2023).

Antoni, S. et al. Rotavirus genotypes in children under five years hospitalized with diarrhea in low and middle-income countries: results from the WHO-coordinated global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. PLOS Glob Public. Health. 3, e0001358. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001358 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Impact of nutrition and rotavirus infection on the infant gut microbiota in a humanized pig model. BMC Gastroenterol. 18, 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0810-2 (2018).

Heylen, E. et al. Rotavirus Surveillance in Kisangani, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, reveals a high number of unusual genotypes and gene segments of animal origin in non-vaccinated symptomatic children. PLoS ONE. 9, e100953. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0100953 (2014).

Zeller, M. et al. Emergence of human G2P[4] rotaviruses containing animal derived gene segments in the post-vaccine era. Sci. Rep. 6, 36841. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36841 (2016).

Tacharoenmuang, R. et al. Full genome characterization of Novel DS-1-Like G8P[8] Rotavirus strains that have emerged in Thailand: reassortment of bovine and human Rotavirus Gene segments in emerging DS-1-Like Intergenogroup Reassortant strains. PLoS ONE. 11, e0165826. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165826 (2016).

Matthijnssens, J. et al. Reassortment of human Rotavirus Gene segments into G11 Rotavirus strains. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16, 625–630. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1604.091591 (2010).

Midgley, S. E., Hjulsager, C. K., Larsen, L. E., Falkenhorst, G. & Böttiger, B. Suspected zoonotic transmission of rotavirus group A in Danish adults. Epidemiol. Infect. 140, 1013–1017. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268811001981 (2012).

Estes, M. K., Kang, G., Zeng, C. Q. Y., Crawford, S. E. & Ciarlet, M. Pathogenesis of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis. In: (eds Chadwick, D. & Goode, J. A.) Novartis Foundation Symposia, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 82–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470846534.ch6. (2008).

Betts, M. J. & Russell, R. B. Amino Acid properties and consequences of substitutions. In: (eds Barnes, M. R. & Gray, I. C.) Bioinformatics for Geneticists, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 289–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470867302.ch14. (2003).

Mohanty, S. K. et al. A point mutation in the Rhesus Rotavirus VP4 protein generated through a Rotavirus Reverse Genetics System attenuates biliary atresia in the murine model. J. Virol. 91, e00510–e00517. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00510-17 (2017).

Gorziglia, M. et al. Sequence of the fourth gene of human rotaviruses recovered from asymptomatic or symptomatic infections. J. Virol. 62, 2978–2984. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.62.8.2978-2984.1988 (1988).

Ball, J. M., Mitchell, D. M., Gibbons, T. F. & Parr, R. D. Rotavirus NSP4: a multifunctional viral enterotoxin. Viral Immunol. 18, 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1089/vim.2005.18.27 (2005).

Zhang, M. et al. Mutations in Rotavirus nonstructural glycoprotein NSP4 are Associated with altered virus virulence. J. Virol. 72, 3666–3672. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.72.5.3666-3672.1998 (1998).

MwangiPN et al. Evolutionary changes between pre- and post-vaccine South African group a G2P[4] rotavirus strains, 2003–2017. Microb. Genomics. 8 https://doi.org/10.1099/mgen.0.000809 (2022).

Pager, C. T., Alexander, J. J., Steele, A. D. & South African G4P[6] asymptomatic and symptomatic neonatal rotavirus strains differ in their NSP4, VP8*, and VP7 genes. J. Med. Virol. 62, 208–216. (2000).

Horie, Y., Nakagomi, O. & Masamune, O. Three major alleles of rotavirus NSP4 proteins identified by sequence analysis. J. Gen. Virol. 78, 2341–2346. https://doi.org/10.1099/0022-1317-78-9-2341 (1997).

Dong, Y., Zeng, C. Q. Y., Ball, J. M., Estes, M. K. & Morris, A. P. The rotavirus enterotoxin NSP4 mobilizes intracellular calcium in human intestinal cells by stimulating phospholipase C-mediated inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94, 3960–3965. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.94.8.3960 (1997).

Nhampossa, T. et al. Diarrheal Disease in Rural Mozambique: Burden, Risk factors and etiology of Diarrheal Disease among children aged 0–59 months seeking care at Health Facilities. PLoS ONE. 10, e0119824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119824 (2015).

Aladin, F., Nawaz, S., Iturriza-Gómara, M. & Gray, J. Identification of G8 rotavirus strains determined as G12 by rotavirus genotyping PCR: updating the current genotyping methods. J. Clin. Virol. 47, 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2010.01.004 (2010).

Nhacolo, A. et al. Cohort Profile Update: Manhiça Health and Demographic Surveillance System (HDSS) of the Manhiça Health Research Centre (CISM). Int. J. Epidemiol. 50, 395–395. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa218 (2021).

Potgieter, A. C. et al. Improved strategies for sequence-independent amplification and sequencing of viral double-stranded RNA genomes. J. Gen. Virol. 90, 1423–1432. https://doi.org/10.1099/vir.0.009381-0 (2009).

Korolenya, V. A. et al. Evaluation of advantages of Lithium Chloride as a Precipitating Agent in RNA isolation from frozen vein segments. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 173, 384–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10517-022-05554-8 (2022).

Schbath, S. et al. Mapping reads on a genomic sequence: an algorithmic overview and a practical comparative analysis. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 796–813. https://doi.org/10.1089/cmb.2012.0022 (2012).

QIAGEN CLC Genomics Workbench. n.d. accessed March 4, (2023). https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com

Kearse, M. et al. Geneious Basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 28, 1647–1649. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 (2012).

Pickett, B. E. et al. ViPR: an open bioinformatics database and analysis resource for virology research. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D593–D598. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr859 (2012).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. J. Mol. Biol. 38, 3022–3027. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab120 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all participants of both studies and extend their appreciation to all staff at the site recruitments (hospital, peripheral health facilities and community) and laboratory for all their effort and dedication. Additional thanks goes to Simone Boene for his technical support during the data analysis.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or polices of the World Health Organization/Region office for Africa or other partners.

Funding

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1033572) via the Center for Vaccine Development, USA funded the GEMS study; GAVI via the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Foundation (CDCF), Atlanta, and the World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa (WHO/AFRO), grant number MOA #0.870 − 15 SC; The United States Agency for International Development (USAID), grant number AID-656-F-16-00002 and Fundo Nacional de Investigação (FNI), Moçambique, grant number 245-INV funded the implementation of the surveillance of rotavirus and other enteropathogens in children less than 5 years of age in Manhiça. The whole genome characterization undertaken in this study was supported by The Child Health and Mortality Prevention program (Surveillance), CHAMPS funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation under Grant OPP1126780; The Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia for funds to GHTM-UID/04413/2020 and LA-REAL – LA/P/0117/2020, Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical (IHMT), Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal and the Next Generation Sequencing Unit, and the Division of Virology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, South Africa. The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation financed F. M’s PhD studies, under the grant number 234066. CISM receives core funding from the Mozambican government and the “Agencia Española de Cooperacion Internacional para el Desarollo (AECID).”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FM, EDJ, PM, PC, MM, MG, AM, DV, NN, JPN, TN, SA, CC, GW, PLA, CC, MN and IM: conceptualization, data curation and writing-original draft. KK, JPN, JMM, PLA, MN, CC and IM: funding acquisition and resources. FM, EDJ, CC, MN and IM: investigation and methodology. KK, JPN, JMM, PLA, CC, MN and IM: project administration. MN, CC and IM: supervision. FM: formal analysis. FM: software. FM, EDJ, PM, PC, MM, MG, AM, DV, NN, KK, JPN, TN, SA, GW, JT, UP, JMW, PLA, CC, MN and IM: visualization, validation, and writing-review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Previous Ethics Committee approval was granted by the Mozambican National Bioethics Committee, Ministry of Health, Mozambique, through the reference numbers 11/CNBS/07; IRB 00002657 and 209/CNBS/15; IRB00002657. All the legal guardians/next of kin of the children who participated in this study, signed a written informed consent form.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manjate, F., João, E.D., Mwangi, P. et al. Genomic analysis of DS-1-like human rotavirus A strains uncovers genetic relatedness of NSP4 gene with animal strains in Manhiça District, Southern Mozambique. Sci Rep 14, 30705 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79767-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79767-4