Abstract

The transcriptional regulation of gene expression in the latter stages of follicular development in laying hen ovarian follicles is not well understood. Although differentially expressed genes (DEGs) have been identified in pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory stages, the master regulators driving these DEGs remain unknown. This study addresses this knowledge gap by utilizing Master Regulator Analysis (MRA) combined with the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks (ARACNe) for the first time in laying hen research to identify master regulators that are controlling DEGs in pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory phases. The constructed ARACNe network included 10,466 nodes and 292,391 edges. The ARACNe network was then used in conjunction with the Virtual Inference of Protein-activity by Enriched Regulon (VIPER) for the MRA to identify top up- and down-regulated master regulators. VIPER analysis revealed FOXO1 as a master regulator, influencing 275 DEGs and impacting pathways related to apoptosis, proliferation, and hormonal regulation. Additionally, CLOCK, known as a crucial regulator of circadian rhythm, emerged as an upregulated master regulator in the pre-ovulatory stage. These findings provide new insights into the transcriptional landscape of laying hen ovarian follicles, offering a foundation for further exploration of follicle development and enhancing reproductive efficiency in avian species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a layer hen ages, her productivity and follicle quality decline. The rate of egg production is the most important trait considered in selection for laying1,2. Production rate has been selected for by poultry breeders for many decades2,3,4,5but as hens age there is a decrease both in follicular numbers and quality in the ovary6,7,8. The decline in quality arises from a multitude of factors, including oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and genetic abnormalities9,10. The yolk found in an egg is first developed as a follicle, which is stored in the ovary11. Thus, it is important to note that the number of ova (eggs) is pre-determined in a hen because no more follicles can be produced in the hens life12,13. The process of follicle development as they progress to the next stage towards ovulation in laying hens remains incompletely understood, as it is unknown what master regulators control the process to allow for a single pre-recruitment follicle to be selected to transition to the pre-ovulatory stage.

The intricate process of follicle selection and progression within the ovulatory cycle unfolds through a precisely timed 24–28-h cycle14,15. There are four phases that follicles must develop through in the ovary to make it to ovulation. The first is primordial, followed by primary and pre-recruitment, and finally the stage known as pre-ovulatory. Follicular outcome is established at each stage, with the risk of apoptosis looming during the initial three phases, emphasizing the importance of a follicle’s advancement to the pre-ovulatory stage for successful ovulation. Follicular atresia (which includes apoptosis) is when a follicle degenerates and regresses into the ovary and will never become an egg16. This means it is critical that follicles advance to the final pre-ovulatory stage for ovulation for it to develop into eggs. It must also be noted that the pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory follicles are in the stages at which a definitive follicle hierarchy may be identified, however pre-recruitment follicles are still susceptible to deprioritization and regression (apoptosis), which is part of the reason this follicle selection process is complex. Additionally, hormones and environmental factors also exert significant influence over the reproductive system of chickens.

There are two main cellular layers within the follicle, the granulosa and the theca17,18, which are affected by the hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal axis (HPG axis)19,20,21. The HPG axis regulates reproduction and fertility by connecting the brain to the reproductive system via systemic release of hormones by the pituitary to the ovary. The key hormones in the HPG axis are Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH), Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH), and Luteinizing Hormone (LH). FSH promotes follicular growth and production of estrogens, while LH governs both ovarian development and the ovulation process. Folliculogenesis is also affected by growth regulatory factors and steroid hormones, with GnRH regulating follicular development and steroidogenesis19,22. Thus, it is clear that regulation by the HPG axis is multimodal and has effects on both the ovary and its follicles.

Currently, many differentially expressed genes (DEGs) have been identified in the latter two follicular stages (pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory), but the field is lacking knowledge about what master regulators (and transcription factors) are controlling those DEGs to elicit the gene expression changes that are occurring. Previous studies have analyzed the laying hens ovarian follicles using RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) to examine the granulosa cells and/or theca cells from follicular samples. Hormone associated genes such as Follicle-Stimulating Hormone Receptor (FSHR), Luteinizing Hormone/Choriogonadotropin Receptor (LHCGR), Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein (STAR), and Cytochrome P450 Family 11 Subfamily A Member 1 (CYP11A1) have been found to be associated within the granulosa and/or theca layers to drive steroidogenesis but it is still unknown what drives the biological processes in each follicular phase for the laying hen23,24,25,26,27. If a transcription factor has been previously identified it has been done purely based on analysis of DEGs or pathway data.

To address this complex process, we used master regulator analysis (MRA) which uses DEGs to compare the last two phases of follicular development—the pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory. DEGs in combination with Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks (ARACNe) were used to discover transcription factor/master regulator regulatory gene networks28,29,30,31. This analysis was conducted utilizing Virtual Inference of Protein-activity by Enriched Regulon (VIPER). This is the first study to use this approach to discover and analyze transcription factors for laying hen ovarian follicles and generate the hen ovarian ARACNe network. The use of the ARACNe network in conjunction with VIPER led to the identification of the master regulator Forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1). This master regulator is involved in many critical pathways governing folliculogenesis and is a key regulator of cell proliferation and apoptosis. This study into the transcriptional landscape of laying hen ovarian follicles using this approach, not only addresses a significant knowledge gap but also lays the groundwork for a more comprehensive understanding of the molecular dynamics shaping the reproductive biology and selection process for hen ovarian follicles.

Results

Identification of differentially expressed genes in ovarian follicular recruitment

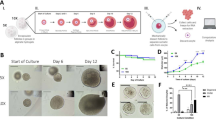

A group of pre-recruitment follicles and the most recently recruited pre-ovulatory follicle were extracted from the ovaries of six laying hens. Total RNA was isolated from these samples and RNA sequencing was performed (as indicated in Materials and Methods) to obtain a complete gene transcriptomic profile for the samples (Figs. 1, 2). The RNA-Seq data were further processed by bioinformatic analysis to obtain the normalized global expression of the samples (Supplementary Figure S1 A–D), which provided a uniform signal with a clear separation of the 6 pre-recruitment samples from the 6 pre-ovulatory samples (see PCA in Supplementary Figure S1D). In addition, differential gene expression analysis was performed using the limma-voom algorithm, yielding 754 significant genes, of which 285 genes were downregulated, and 469 genes were upregulated (see heatmap presented in Fig. 3A). These 754 DEGs are also presented in the volcano plot in Fig. 3B (blue downregulated and red upregulated); where the top 15 upregulated genes in the reds are also labeled with gene symbol, and the top 15 downregulated genes in the blues are also labeled with gene symbol (Fig. 3B). This volcano plot has a cut-off adjusted P-value of < 1.0e-06, which marks the upregulated genes (469) in blue and the downregulated genes (285) in red. Also in this volcano plot, two vertical dashed lines mark the genes that have a log2 fold change (log2FC) greater than 2 in absolute value, i.e. below −2 or above + 2. All details of the parameters obtained in the differential expression analysis for each of these 754 genes are provided in Supplementary Table S2.

Experimental and analytical design. Six laying hens were euthanized to obtain the F5 pre-ovulatory follicle and a group of 3–4 pre-recruitment follicles. RNA was isolated from the follicles and RNA-Seq was performed using Illumina NovaSeq 6000. The RNA-Seq data was analyzed using a differential gene expression analysis. A gene regulatory network was built using the algorithm ARACNe followed by algorithm VIPER in order to identify the gene Master Regulators (Figure was created with BioRender.com using an institutional license sponsored by University of Delaware Office for Research).

Identification of Significant Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) from a group of pre-recruitment and F5 pre-ovulatory follicles from 12-month-old layer hens. (A) Heatmap showing expression signal of the 12-month RNA-Seq samples (columns) for the signature of 754 significant differentially expressed genes (contained in the rows of the map) found in the comparison of pre-ovulatory samples versus pre-recruitment samples (considered as reference). The values shown correspond to the z-scored expression signal across the rows (red represents over-expression, i.e. upregulation, and blue represents under-expression, i.e. downregulation). The heatmap includes a hierarchical clustering of the samples and the genes shown by the dendrograms (calculating the pairwise Pearson correlation between the genes and using a hierarchical ward.D2 clustering method to obtain the dendrograms). At the top of the heatmap, two color bars indicate the sample groups: yellow for pre-ovulatory and green for pre-recruitment. (B) Volcano plot showing differentially expressed genes. The arrows and labels indicate the top 15 genes that are significantly under-expressed (dark blue) and the top 15 genes that are significantly over-expressed (dark red). The horizontal dashed line shows the cut-off for adjusted P-value < 1e-06, i.e. 6, in the -log10(p-value). The vertical dashed line shows the cut-off where |log2(fold-change)|> 2 (i.e. in absolute values). The key displays downregulated (DW), fold change (FC), not significant (NoSig), and upregulated (UP).

Matrix Metallopeptidase 1 (MMP1), Matrix Metallopeptidase 13 (MMP13), Lysyl Oxidase (LOX), Matrix Metallopeptidase 10 (MMP10), Lecithin-Cholesterol Acyltransferase (LCAT), Secreted Frizzled Related Protein 4 (SFRP4), and Tropomyosin 1 (TPM1) were significantly upregulated in our data set25,32,33,34,35,36,37. Additionally, Cyclin B1 (CCNB1), MYCL Proto-Oncogene (MYCL), and Niemann-Pick disease Type C1 (NPC1) are DEGs that are shown to be significantly downregulated in our analysis (Fig. 3B)38,39,40,41.

Construction of an ovarian gene regulatory network based in mutual information

To identify how the differentially expressed genes may be regulated by master regulators (MRs), that is, by Transcription Factors (TFs), which are key players in a given biological experimental set, we built a Gene Regulatory Network (GRN) using the algorithm ARACNe (which is based in the analysis of Mutual Information between genes using the global transcriptomic expression profile of multiple samples). This GRN was generated using a large expression dataset of 381 ovarian human samples for which we had full expression profiles. This human network was then mapped to chicken orthologous genes to create a homologous chicken gene regulatory network (as described in Methods). Specifically, 381 RNA-Seq expression samples containing 58,616 genes were taken and filtered. After several steps of filtering, which included removing genes that did not have relevant expression signal (i.e. genes that had zeros or very low signal in most of the samples), we applied the ARACNe3 algorithm (using a list of 2,490 human gene regulators, i.e., human TFs) to generate a bipartite network that included the regulators and the corresponding regulons (i.e., the sets of genes regulated by each TF). This allowed us to generate a human network that had 19,635 genes and 670,967 links or edges (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the human genes were mapped to hen (as indicated in Methods) to generate a hen gene regulatory network that included 10,446 nodes and 292,931 edges (Fig. 4B-D). To prove that this mapping does not lose significant biological information for ovarian regulation we mapped on both the human and hen GRN a set of 15 gene that are known to be related with ovarian function, and, as it can be seen in Figs. 4E and 4F, this mapping located all of these genes and their networks in both the human and in the hen network.

Human and chicken global gene regulatory networks. (A) Global gene co-expression network obtained with the ARACNe3 algorithm for human ovarian samples (including 19,635 nodes and 670,977 edges) together with the corresponding chicken network (red subnetwork, showed in (B), (C) and separated in (D)) generated as a replication of the human network via all orthologous genes identified in chicken (including 10,446 nodes and 292,391 edges between these nodes). To map the orthologous genes in human, we used the list of 10,682 genes from chicken that showed signal in the RNA-Seq dataset produced in this work. The grey subnetwork corresponds to the part of the human global network that are not mapped to chicken. Human (E) and hen (F) subnetworks were created using 15 genes that are well known in female reproductive literature. These genes were extracted from the human and hen ARACNe networks that were created in the previous steps.

Identification of ovarian gene master regulators (MRs) using VIPER algorithm

The ARACNe network and the differential expression data matrix obtained with the RNA-Seq samples of chicken were then used in VIPER/MRA pipeline to identify the MR genes in the pre-ovulatory follicles. This resulted in the identification of 10 upregulated genes (red) and 10 downregulated genes (blue) that the VIPER algorithm recognizes as transcription factor master regulators (Fig. 5, and Supplementary Table S1). The algorithm provides these transcription factors, as the most significant regulators of the gene network, with a set of parameters measuring their significance, shown in Fig. 5 and also listed in Supplementary Table S1. These parameters are: the P-value of each regulator (e.g. 0.00031 for BASP1 and 0. 000,225 for OVOL2); the P-values adjusted using FDR (i.e. multiple testing correction done using False Discovery Rate); the sign of the regulation (positive in red and negative in blue, Fig. 5); the number of genes included in each regulon of these 20 MRs (e.g. 191 genes are co-regulated by the gene BASP1 and 42 genes are co-regulated by the gene OVOL2); and the normalized enrichment score (NES) calculated by VIPER (Supplementary Table S1). Qualitatively, the VIPER output plot (Fig. 5) also shows the inferred activity (Act) of these top gene regulators in the first column and the differential expression (Exp) in the second column. The last column of the VIPER plot shows the number of genes that can be found in each regulon, i.e. the group of genes that are regulated together by each master regulator. In addition, the subnetworks of each of these master regulators were separated from the global networks and isolated for further analysis (Fig. 6). Most of these 20 regulators were not included in the signature of 754 DEGs because even though most of them were significant in the differential expression analysis, their expression change is not large enough to pass the threshold of −2/ + 2 (log2FC) in their fold change, thereby further underscoring employment of the VIPER algorithm. We provide the values of each of these 20 MRs in the differential expression analysis in Supplementary Table S3.

Top Master Regulators identified by VIPER. Virtual inference of protein activity by enriched regulon analysis (VIPER) was employed for accurate assessment of protein activity from gene expression data. The projection indicates negative (blue) and positive (red) targets for each transcription factor (TF) for pre-ovulatory versus pre-recruitment. This was inferred by ARACNe and correlation analysis when reverse engineering the regulatory network (vertical lines resembling a bar-code), on the x-axis where the genes in the gene enriched sets (GESs) were rank-sorted from the one most down-regulated to the one most upregulated in pre-ovulatory versus pre-recruitment. The two-column heatmap displayed on the right side of the figure shows inferred activity (first column) and differential expression (second column). The number of genes for each regulon is indicated In the last column.

Subnetworks regulated by indicated master regulators (MRs). Chicken gene regulatory network (bipartite network of transcription factor (TF) regulators & gene regulons) obtained after running VIPER algorithm on ARACNe network and selecting 20 Master Regulators (3,648 nodes & 6,461 edges). The 20 Master Regulators are presented as red ellipses (10 up-regulated TFs) & as blue ellipses (10 down-regulated TFs).

Clock Circadian Regulator (CLOCK) and Basic Helix-Loop-Helix Family Member E40 (BHLHE40) are both involved in controlling circadian rhythm and were found to be significantly upregulated transcription factors (TFs). SET Domain Containing 7 (SETD7) was also significantly upregulated and, together with FOSL2 (member of the FOS gene family, encoding a leucine zipper protein that can dimerize with proteins of the JUN family, thereby forming the transcription factor complex AP-1), had the largest regulon size with 519 and 539 genes, respectively. The MRA showed both FOXO1 and Follistatin (FST) as significantly downregulated TFs. FOXO1 is known for regulating proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle signaling and has been previously identified in granulosa cells across diverse species, including hens, sheep, mice, bovines, and humans42,43,44. FST is an activin-binding protein that interacts with the TFGβ superfamily45,46. FOXO1 and FST had 275 genes and 263 genes in their respective regulons. Both High Mobility Group AT-Hook 2 (HMGA2) and Histone Deacetylase 10 (HDAC10) affect apoptosis and cell cycle response. HMGA2 was significantly downregulated and had the biggest regulon size of 482 genes for downregulated TFs. HDAC10 had the second smallest regulon size with 50 genes.

Validating the master regulators using the GlobalTest outcome method

To investigate the robustness of this set of 20 genes found as key MRs in our analysis, the GlobalTest was employed, which is a statistical algorithm that tests groups of covariates (features) for association with a response variable (that is the state, status or phenotype tested). In this way, it can be evaluated how each one of the gene MRs found (i.e. the features) is associated with the phenotypes studied: pre-ovulatory or pre-recruitment. This statistical method is tailed for datasets containing multiple covariates and a response variable. It can determine whether a specific group of covariates (genes) is associated with the response (biological condition)47,48. The results of the GlobalTest are illustrated in Fig. 7A-B, which includes in 7A a plot showing the evaluation of each one of the 20 genes-features and in 7B a plot showing the association of each sample with its phenotype. The hierarchical clustering graph indicates that 4 genes: FST, FOXO1, TCF7, and OVOL2 (Ovo Like Zinc Finger 2) have the strongest association with the pre-recruitment follicles and are grouped together. HOXB3, ZNDF521, Transcription Factor 12 (TCF12), Lysyl Oxidase Like 2 (LOXL2), Brain Abundant Membrane Attached Signal Protein 1 (BASP1), and ETV1 were in the same hierarchical cluster and associated with the pre-ovulatory follicle. Figure 7B shows that all samples were correctly associated with either the pre-recruitment (6 green bars) or pre-ovulatory phenotype (6 red bars). Finally, in a complementary analysis, we investigated the overlap of the gene regulons corresponding to each of the 20 MRs. We performed a pair-wise comparison of all the genes in the regulons to determine which ones were shared. The symmetric matrix uses the number of shared genes, and an odds ratio can be calculated for each intersection to better show the relevance of each overlap (Fig. 7C-D).

Global test analysis. Result plots from the globaltest R package. (A) The first plot (top) represents the P-values of the tests of individual component covariates (genes) of the alternative (~ A + B; ~ A ~ B). The plotted genes are ordered in a hierarchical clustering graph. The distance measure used for the graph is absolute correlation distance. In black is colored parts that have a significant multiplicity-corrected P-value, which indicates the ones that are most clearly associated with the response variable (sample type, green for pre-recruitment and red for pre-ovulatory). The second plot (bottom) is similar except that the Y axis is represented by the weighted test statistic. This corresponds to the unstandardized test statistics weighted for the relative weights of the covariates in the test. The black bars and stripes signify mean and standard deviation of the bars under the null hypothesis. (B) Plot for visualizing the influence of the subjects on the test result. As in the previous plot (A), the samples are ordered in a hierarchical clustering graph. On the Y-axis is represented the posterior effect (the first partial least squares component of the data, which can be interpreted as a first order approximation of the estimated linear predictor under the alternative). In the resulting plot, large positive values correspond to subjects that have a much higher predicted value under the alternative hypotheses than under the null (pre-recruitment samples), whereas large negative values correspond to subjects with a much lower expected value under the alternative than under the null (pre-ovulatory samples). (C) Lower triangle of symmetrical matrix. The number corresponds to the odds ratio of the number of genes shared by each regulon obtained from the VIPER analysis. The regulons are color coded (red for the overexpressed genes in pre-ovulatory condition and blue for the underexpressed genes in pre-ovulatory condition). (D) The odds ratio of the number of genes shared by each regulon obtained from the VIPER analysis is indicated. The regulons are color coded (red for the over-expressed genes in pre-ovulatory condition and blue for the under-expressed genes in pre-ovulatory condition).

Verification of master regulators by qRT-PCR

Validation was performed by qRT-PCR on the master regulators. The results showed that up-regulated TFs: BASP1, Zinc Finger Protein 521 (ZNF521), SETD7, LOXL2, TCF12, and Fos-related antigen 2 (FOSL2) were significantly expressed in the most recently recruited F5 pre-ovulatory follicle (Fig. 8A). qRT-PCR analysis was additionally performed on F5 pre-ovulatory and pre-recruitment follicles from broiler breeders. Among these upregulated MR samples, BASP1, ZNF521, FOSL2, and HOXB3 exhibited significance. Additionally, three of the ten down-regulated transcription factors; FST, HMGA2, and OVOL2, were found to be significantly expressed in the pre-ovulatory follicle as well. Both FST and HMGA2 were also significantly expressed in the F5 pre-ovulatory from broiler breeder (Fig. 8B).

Validation of protein expression in pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory follicles

ARACNe, RNA-Seq based differential gene expression analysis, and VIPER were used in sequence to identify Master Regulators (MRs). To validate these MRs at the protein level, total protein was isolated from pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory (F5) follicles for twelve-month-old layer hens and probed for FOXO1, FST, and CLOCK using western blot analysis. GAPDH was used as loading control. FOXO1 and FST protein levels were enhanced in pre-recruitment follicles and CLOCK protein levels was enhanced in pre-ovulatory (F5) follicles (Fig. 9).

Western blot validation in pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory follicles of laying hens. Western blot validation of proteins identified as Master Regulators (MRs) based on ARACNe and VIPER analysis for twelve-month-old layer hens. GAPDH is used as loading control. Hen 1 and Hen 2 are two independent biological replicates from the same cohort.

Discussion

Research has been limited in identifying transcription factors that drive gene regulatory networks in laying hen ovarian follicles. Most approaches that analyze hen ovarian follicles use differential gene expression and pathway analyses which leads to an incomplete understanding of the complex orchestration of the transcriptional hierarchy and signaling. Identification of regulatory transcription factors that control a significant subset of genes that bring about phenotypic and physiological responses is key to interrogating the process of follicular development within the laying hen ovary.

To this end, this study is the first to generate an ARACNe network for laying hen ovarian follicles and then use that network in the VIPER/Master Regulator Analysis. The ARACNe network for laying hen ovarian follicles is being made available as a community resource that maps ovarian gene interactions comprehensively. Next, we sampled follicles from six laying hens at twelve months of age. Our differential gene expression analysis showed clear separation between the two follicular groups (pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory). After the DEGs were identified, they were overlaid on the human ovarian ARACNe network to construct the hen ARACNe network. The hen ARACNe network resulted in 10,466 nodes and 292,391 edges. The ARACNe network generated for the hen is ~ 50% of that of the human network due to the hen having many less identified genes and transcripts in literature, which is an unavoidable drawback of our approach. This network and the DEGs were used for VIPER analysis for the MRA. The MRA indicates the top ten up and down regulated master regulators.

When analyzing the master regulators, we further identified and validated FOXO1 at the protein level, which is part of the forkhead transcription factor family (FOXO). FOXO1 is recognized for its regulatory roles encompassing proliferation, apoptosis, cell stress response, and cell cycle signaling, and has been previously identified in granulosa cells across diverse species, including hens, sheep, mice, bovines, and humans42,43,44. In laying hens, the primary focus on FOXO1 has centered on investigating the potential antioxidative effects of melatonin to mitigate oxidative stress-induced apoptosis49,50,51. Furthermore, FOXO1 has been implicated in inducing granulosa cell apoptosis by inhibiting cell proliferation and steroid hormone synthesis. This was noted in a conditional knockout study targeting FOXO1 in mice which revealed the involvement of FOXO1 in preventing proliferation and promoting apoptosis of ovarian granulosa cells52,53.

In this study, FOXO1 emerged as a down-regulated transcription factor in pre-ovulatory follicles, influencing 275 of our DEGs. Among these, Activin A receptor, type I (ACVR1) and Superoxide Dismutase 1 (SOD1) DEGs were found to have a negative correlation with FOXO1, implying that their activity or expression increases when FOXO1 is suppressed. ACVR1 was observed to collaborate with SMAD1 and ID3, promoting proliferation and providing antiapoptotic effects in laying hen granulosa cells54. In a hen study investigating melatonin and FOXO1, SOD1 was identified as an antioxidative gene that aids in apoptosis and was observed to be upregulated when FOXO1 expression was decreased49, which is consistent with our own protein data. Both ETS Proto-Oncogene 1 (ETS1) and Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) were found to be directly correlated with FOXO1 expression in the FOXO1 gene regulon. ETS1, involved in cell death processes has been reported to show correlated expression with FOXO1 in some non-ovarian models55,56, and was found to be activated by FOXO1 in a rat ovarian study43. KLF5, implicated in cell cycle control, apoptosis, and differentiation, has been shown to be influenced by FOXO1 in cardiomyocytes and skeletal muscle atrophy57,58,59. FOXO1 directly binds to the KLF5 promoter in cardiomyocytes of mice, correlating with KLF5 expression59. Additionally, in our analysis, ADAM Metallopeptidase Domain 12 (ADAM12), Fibroblast Activation Protein Alpha (FAP), MMP10, and SFRP4 were all noted on the volcano plot (Fig. 3B) as part of the top 15 upregulated DEGs, exhibiting the most significant P-value (with fold-change exceeding 2). Specifically, ADAM12 and FAP are associated with the MAPK pathway, while MMP10 is linked to the extracellular matrix. All these DEGs are also under the regulatory control of FOXO1.

In the intricate network of hormonal regulation, FOXO1 is recognized for its involvement in controlling hormones such as GnRH, FSH, and LH, and has been noted to play a role in the regulation of the gonadotropin gene53. Moreover, FOXO1 is known to upregulate genes related to apoptosis, such as Fas ligand (FasL), tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL), and BCL2-like 11 (BCL2LL)52. FOXO1 inactivation by the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, regulated by FSH through cAMP and PKA, has been well-documented in literature43,60,61,62. This pathway induces FOXO1 phosphorylation, leading to its translocation from the nucleus to the cytosol, rendering it inactive. When located in the nucleus in an unphosphorylated state, FOXO1 promotes follicular atresia and inhibits the steroidogenic biosynthesis pathway. Additionally, FOXO1 represses several FSHR targets, including CCND2, lipids, and the steroidogenic pathway, suggesting a regulatory loop between FOXO1 and FSHR63. The diverse roles of FOXO1, encompassing apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, stress response, and proliferation, make its identification and validation as a master regulator pivotal in understanding the impact this transcription factor has on pre-recruitment follicles.

FOXO1, along with two other identified MRs, FST (which we also show to be down-regulated at the protein level) and SRY-Box Transcription Factor 17 (SOX17), also affect the WNT/beta-catenin pathways, which are important for cell proliferation and differentiation in follicle development. The Wnt signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in follicular development, with emerging evidence suggesting the involvement of FOXO transcription factors in its regulation64,65. Approximately half of all FOXO transcription factors in mammals have been reported to play roles within the Wnt pathway65. Specifically, FOXO1 has been identified as an inhibitor of the β-catenin/TCF7L2 interaction66. FST plays a role in inhibiting follicle stimulation hormone (FSH) release. FST functions downstream of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and in mice, FST expression was decreased when β-catenin was knocked out67,68. Furthermore, FST can inhibit FSHR from binding with activin which is needed for the transition to the pre-ovulatory stage. Our validation here of FST being down regulated in the pre-ovulatory follicle confirms with findings from a previous study analyzing geese69,70. SOX17 has emerged as another master regulator found to be down-regulated in the pre-ovulatory follicles. Known for its role in embryonic development regulation and its ability to suppress proliferation, SOX17 also acts to downregulate the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is vital for pre-ovulatory follicles71,72. The down-regulation of SOX17 carries considerable significance, particularly given the rapid growth and development processes underway in the pre-ovulatory follicles.

Hormones and environmental factors play a major role in the reproductive system of chickens. In laying hens, the hens lay cycles are dependent upon getting optimal hours (12 to 16) of light and dark each day. Light triggers the hypothalamus to release GnRH, which in turn signals the anterior pituitary to release FSH and LH, ultimately signaling the ovary. Therefore, circadian rhythm is a key component in the egg laying cycle which will affect how often a hen lays an egg. Master regulator CLOCK is involved in regulating circadian rhythm and is found to be significantly upregulated in the pre-ovulatory stage and plays a crucial role regulating circadian rhythm response. The identification and validation of this transcription factor indicates the key role that the light cycle plays in ovulation in the hen. Overexpression of CLOCK was noted to down-regulate CCNB1 in porcine granulosa cells39. CLOCK was demonstrated in a previous study to be a possible transcriptional regulator of the StAR gene as well73. CLOCK will form a heterodimer with Basic Helix-Loop-Helix ARNT Like 1 (BMAL1) and together they become primary drivers of positive circadian driven gene expression. BMAL1 has been noted to regulate STAR in mice and therefore play a role in the steroid biosynthesis pathway which leads to the production of progesterone which is vital in the pre-ovulatory phase74. The LH surge that is necessary for ovulation has been noted to function with the activation of CLOCK and BMAL173,75,76. The identification and validation of CLOCK as a master regulator here emphasizes this master regulators importance in regulating circadian rhythm and impacting the steroid biosynthesis pathway.

In summary, this study identifies master regulators governing gene regulatory networks in laying hen ovarian follicles by introducing a novel approach involving the construction of an ARACNe network specific to laying hens and subsequent analysis using the VIPER/Master Regulator Analysis. Both FOXO1 and CLOCK were not significantly expressed in the qRT-PCR analysis, highlighting the importance of the VIPER analysis, which identified the relevance of these regulators. Insights from VIPER guided the selection of proteins for validation by western blot analysis, where FOXO1 showed decreased levels and CLOCK showed increased levels in pre-ovulatory follicles, further validating the VIPER findings. These results demonstrate the strength of the VIPER analysis, as relying solely on qRT-PCR data would have led to FOXO1 and CLOCK being overlooked due to their lack of significant expression at the RNA level. Further, the hen ARACNe network serves as a community resource that can be widely employed to interrogate various aspects of hen ovarian biology. Our focus on FOXO1, as a master regulator, reveals its multifaceted role in apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, and hormonal regulation, offering crucial insights into the intricate processes of follicular development. This study also noted the possible integration of FOXO1 with FST and SOX17 into the broader WNT/beta-catenin pathways providing a comprehensive view of their collective impact on follicle development. Additionally, the investigation into the master regulator CLOCK, highlights their significant upregulation in the pre-ovulatory stage, emphasizing its vital role in circadian rhythm control and its influence on the reproductive system in laying hens. The downregulation of the differentially expressed cell cycle signaling gene, CCNB1, associated with CLOCK overexpression, further underscores the impact of this master regulator on key cellular processes. Collectively, these findings contribute valuable insights into the transcriptional landscape and regulatory mechanisms governing laying hen ovarian follicles, laying the groundwork for further exploration of the complex interplay of differentially expressed genes and master regulators in avian reproductive biology.

Materials and methods

Animals and sample collection

Fifty Specific Pathogen Free White Leghorn hens were obtained from Charles River Laboratories at six weeks of age and housed at the University of Delaware Agricultural Research Farm. The hens were housed individually in a temperature-controlled environment (21.1 ̊C ± 6) with 15 h of light per day as per commercial standards. Hens had ad libitum access to both feed and water. Egg-laying events were recorded daily for each hen. Six hens with the highest egg laying rate at 51 weeks of age were selected and euthanized by cervical dislocation. A cluster of 3–4 pre-recruitment follicles and the F5 pre-ovulatory follicle were obtained from the ovaries for RNA-Seq. Pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory follicles were also obtained for broiler breeder ovaries for additional validation. All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Delaware Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations.

To obtain the follicles, pre-recruitment and pre-ovulatory follicles were extracted out of the ovary17. The pre-recruitment follicles (6–8 mm) were collected and groups of 3–4 pre-recruitment follicles were randomly selected and flash frozen (Fig. 2). The hierarchical order was determined for the pre-ovulatory follicles (10–40 mm) once they were extracted. Each pre-ovulatory follicle was cut open to allow ooplasm to be released. The follicle was then washed with 1 × PBS and stored in a cryovial in liquid nitrogen until later analysis occurred.

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol RNA extraction reagent (Invitrogen Cat. No. 15596018), according to manufacturers instructions as previously described77. The quality, quantity, and concentration were evaluated with an Advanced Analytical Technologies, Inc. (AATI) Fragment Analyzer at the Delaware Biotechnology Institute (DBI) in Newark, DE (Fragment Analyzer Systems | Agilent, n.d.). The RNA samples had to have an RNA quality number (RQN) of ≥ 7.8 to move forward in this process, ensuring that the RNA was of high quality for further processing. Six samples of each follicle type (ones with highest RQN #) were used for RNA-Seq. The hen dataset consists of a total of 12 samples, divided into two groups of pre-recruitment (samples AA01 to AA06) and pre-ovulatory (samples AA07 to AA12). Libraries were constructed and paired-end 100 bp sequencing runs were carried out on the Illumina Novaseq 6000 as previously described78. FASTQ-format files were generated for the raw reads79, which were assessed for quality, trimmed, and filtered, and finally mapped to the chicken reference genome (Mar. 2018 release from ENSEMBL, GRCg6a/galGal6)80,81. Counts were generated in table format for 12,471 unique genes.

TCGA-OV dataset

Transcriptomic datasets. The Ovarian Cancer dataset (TCGA-OV) was downloaded from the public repository (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). This data collection consists of 381 RNA-Seq samples from newly diagnosed patients with ovarian cancer, and they include 58,616 genes. We employed a cancer dataset to capture as many molecular interactions as possible to comprehensively map ovarian genetic interactions. A normal ovarian dataset would not allow for such a rich diversity of interactions. Further, mammals and hens have been shown to have many similar characteristics in the maturation of their ovarian follicles82. Genes that had 0 counts (2,858 genes) and 1 count (542 genes) for all samples were removed. Genes with low expression levels were excluded, as defining low expression is subjective. Genes with total values below the first quartile were also eliminated and so were those that were in the left tail of the expression distribution. For the remaining genes, the standard deviation (SD) was calculated, and the genes were sorted by their decreasing SD, and the top 10,000 genes with the highest SD were selected for inclusion in the dataset.

NaRnEa—ARACNe

An interaction network for an ovarian dataset using NaRnEa – ARACNe algorithm was built83. The gene identifiers were transformed to Entrez IDs as the collection of transcription factors is stored in this format. As described in the R package vignette (https://github.com/califano-lab/NaRnEA), the algorithm consists of several steps, briefly described next. The gene expression profiles are standardized into counts per million (CPM) and transformed to narrow down potential transcriptomic regulators. A network topology was generated to reduce correlation, using a 63% subsampling proportion. Mutual information was assessed using adaptive partitioning, with a null distribution estimated through adaptive partitioning. A context-specific ensemble ARACNe3 transcriptional regulatory network was created, and mutual information between regulators and targets was computed using complete gene expression profiles. This information was used to calculate the Association Weight for NaRnEA.

Hen data analysis

Using the hen dataset described above, a differential expression analysis using limma-voom was performed84. Normalization factors were calculated to be used downstream in the analysis. Low expressed genes were filtered and checked. The multidimensional scaling plot was used to identify the grouping of the samples. Those of similar phenotype were expected to be grouped together and further from those of a different phenotype.

A voom transformation was performed and the variance weights were calculated. The model was specified to be fitted as voom uses variances of the model residuals. The counts were transformed to log2 CPM (where “per million reads” is defined based on the normalization factors that were calculated earlier), a linear model was fitted to the log2 CPM for each gene, the residuals were calculated, and a smoothed curve was fitted to the sqrt (residual standard deviation) by average expression. The smoothed curve was used to obtain weights for each gene and sample that were passed into limma along with the log2 CPMs. A linear model was fitted in limma, and the desired contrast for each gene was estimated. An empirical bayes was used for smoothing of standard errors (shrinks standard errors that are much larger or smaller than those from other genes towards the average standard error). To obtain a table with the differentially expressed genes for our conditions, we selected genes with P < 1e-06 which were represented on the heatmap (Fig. 3A). Further filtering was done using log2 FC > 2 in absolute values, to select the most biologically relevant genes (Fig. 3B).

Mapping of hen genes on the human network

All of the genes present in the hen RNA-Seq expression data were then mapped to their orthologous human genes. BiomaRt package mapping to Ensembl was used for this purpose (https://www.ensembl.org/info/data/biomart/index.html). Analysis was started with 11,046 unique hen genes. These genes were then mapped using the R package biomaRt 2.60.0 to the human genes using the Ensembl database version 105 (v105). With this procedure 10,682 genes were obtained that mapped to human genes, of which 10,446 mapped to unique human genes. The resulting genes were then mapped on top of the previously computed human ARACNe3 gene regulatory network, identifying the hen genes on the human network (Fig. 4A-C). The human genes that did not map to hen were then subtracted, which allowed for generation of a hen gene regulatory network that included 10,446 nodes and 292,931 edges (Fig. 4D).

VIPER

VIPER, an algorithm that allows for the computational inference of protein activity from gene expression profile data; considering the genes directly regulated by a specific protein, such as transcription factors, as indicators of its activity85. VIPER includes transcriptional targets most directly affected by a proteins activity inside the regulon. It considers factors such as the regulators mode of action, regulator-target gene interaction confidence, and the pleiotropic nature of target gene regulation. VIPER can be applied not only to transcription factors but also to signal transduction proteins. Using this algorithm, master regulators can be inferred for the human and chicken network. The top 10 most enriched regulators were selected (up and downregulated) for the network. This was done for our two biological conditions, pre-ovulatory and pre-recruitment (Fig. 5). In addition, the subnetworks of each of these master regulators were separated from the global networks and isolated for further analysis (Fig. 6).

Coefficient ratio

For each of the master regulators, we calculated a coefficient that represents the probability that each of them shares genes as a function of their size (Fig. 7C,D), using the following formula:

Odds ratio = n shared genes n genes total/n regulon 1·n regulon 2.

Global test

The global test is a statistical method for datasets with many covariates and a response variable86. It can determine whether a specific group of covariates (genes) is associated with the response (biological condition). Its effective at detecting weak associations among numerous covariates. The test uses regression models based on the response variable type and can adjust for confounding effects caused by correlated nuisance covariates. The globaltest package provides additional features, including diagnostic plots to visualize results, multiple testing procedures for analyzing multiple tests on the same data, and tailored functions for specific applications, like gene set testing. This test allows users to measure the weight of each master regulator for each biological condition. This numeric value represents how important (weight) each master regulator is for the characterization of their corresponding group or biological condition (Fig. 7A). This enables the selection of the most relevant master regulators for further validation. The characterization of each sample for its biological group can be viewed using the master regulator signature (Fig. 7B).

Quantitative RT-PCR

To validate the findings in the study, follicular samples used for RNA-Seq were also used for qRT-PCR validation. The cDNA was synthesized using Thermo Scientific Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit for RT-qPCR with dsDNase to provide a total of 10 µL of cDNA (#K1672). The reaction was composed of 1 µg of RNA (made to be 10 µL of cDNA), 4µL of the 5 × Reaction Mix, 2 µL Maxima Enzyme Mix, 4 µL of nuclease-free ddH2O for a total reaction volume of 20 µL. The reaction was incubated for 10 min at 25 °C, 20 min at 50 °C, and terminated by 85 °C for 5 min. qRT-PCR was performed on QuantStudio3 Real-Time System using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The total reaction consisted of 6 µL of nuclease-free ddH2O, 2 µL cDNA template, 1 µL forward primer, 1 µL reverse primer, and 10 µL PowerUP SYBR Green Master Mix 2x. This provided a total reaction volume of 20 µL. The thermocycling program was 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, Melting temperature of primer minus 0.1 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 1 min. After the 40 cycles were complete the thermocycler ramped to 95 °C for 15 s and then 60 °C for 1 min. The final step was 95 °C for 15 s. Primers used for amplification can be found on Supplementary Table S4. GAPDH was used as the housekeeping gene. To calculate gene expression levels the 2-∆∆ctmethod was followed87as previously described83. Data are expressed as relative mRNA levels (relative to GAPDH rRNA expression) showing the mean ± SD. Data are representative from 3 independent experiments, each done in triplicate. P values were calculated using a two-sample unpaired Welch t-test. ns, not significant.

Western blot analysis

To detect protein levels in follicular samples, the same cohort of hens was employed for western blot analysis. Follicular tissue from two independent pre recruitment and pre-ovulatory samples was digested using RIPA buffer. Protein concertation was measured using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific #23,225), with 20 μg of sample per well. Proteins were separated using 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Blocking was carried out in 5% non-fat dry milk (BioRad #1,706,404) for one hour at room temperature followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with primary antibody – FOXO1 (Thermo Fisher #BS-9439R), FST (Thermo Fisher #PA519787), CLOCK (Thermo Fisher #PA1520), and GAPDH (Cell Signal #2118). After washing, the membrane was incubated with secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked; Cell Signal #7074) for one hour at room temperature followed by chemiluminescent detection using the Amersham ECL detection kit (Cytiva #RPN2105). The antibodies used are documented in Supplementary Table S4, with GAPDH serving as the loading control. BioRad Plus Protein All Blue Prestained protein standard (#1,610,373) was used for protein size reference bands.

Data availability

The raw and normalized data files for RNA-Seq are deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE266767; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE266767).

References

Ciccone, N., Sharp, P., Wilson, P. & Dunn, I. Expression of neuroendocrine genes within the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis of end of lay broiler breeder hens. (2003).

Wolc, A., Arango, J., Settar, P., OSullivan, N. P. & Dekkers, J. C. Evaluation of egg production in layers using random regression models. Poult Sci 90, 30–34. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2010-01118 (2011).

Bain, M. M., Nys, Y. & Dunn, I. C. Increasing persistency in lay and stabilising egg quality in longer laying cycles. What are the challenges? Br Poult Sci 57, 330–338, https://doi.org/10.1080/00071668.2016.1161727 (2016).

Kidd, M. & Anderson, K. Laying hens in the US market: An appraisal of trends from the beginning of the 20th century to present. Journal of Applied Poultry Research 28, 771–784 (2019).

Luo, P. T., Yang, R. Q. & Yang, N. Estimation of genetic parameters for cumulative egg numbers in a broiler dam line by using a random regression model. Poult Sci 86, 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/ps/86.1.30 (2007).

Palmer, S. S. & Bahr, J. M. Follicle stimulating hormone increases serum oestradiol-17 beta concentrations, number of growing follicles and yolk deposition in aging hens (Gallus gallus domesticus) with decreased egg production. Br Poult Sci 33, 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071669208417478 (1992).

Hao, E. Y. et al. Melatonin regulates the ovarian function and enhances follicle growth in aging laying hens via activating the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Poult Sci 99, 2185–2195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2019.11.040 (2020).

Lillpers, K. & Wilhelmson, M. Age-dependent changes in oviposition pattern and egg production traits in the domestic hen. Poult Sci 72, 2005–2011. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0722005 (1993).

Vollenhoven, B. & Hunt, S. Ovarian ageing and the impact on female fertility. F1000Res 7, https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16509.1 (2018).

Moghadam, A. R. E., Moghadam, M. T., Hemadi, M. & Saki, G. Oocyte quality and aging. JBRA Assist Reprod 26, 105–122. https://doi.org/10.5935/1518-0557.20210026 (2022).

Smith, A. H. Follicular permeability and yolk formation. Poultry Science 38, 1437–1446 (1959).

Oguike, M., Igboeli, G. & Ibe, S. Effect of Induced-moult on the Number Small Ovarian Follicles and Egg Production of Old Layers. Int. J. Poult. Sci 5, 385–389 (2006).

Su, H., Silversides, F. G. & Villeneuve, P. Ovarian morphology and follicular development in sex-linked imperfect albino (s(al)-s) and nonalbino hens before or after a forced moult. Br Poult Sci 36, 645–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071669508417809 (1995).

Sharp, P. J. Photoperiodic control of reproduction in the domestic hen. Poult Sci 72, 897–905. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0720897 (1993).

Silver, R. Circadian and interval timing mechanisms in the ovulatory cycle of the hen. Poult Sci 65, 2355–2362. https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.0652355 (1986).

Johnson, A. L. Granulosa cell apoptosis: conservation of cell signaling in an avian ovarian model system. Biol Signals Recept 9, 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1159/000014628 (2000).

Gilbert, A. B., Evans, A. J., Perry, M. M. & Davidson, M. H. A method for separating the granulosa cells, the basal lamina and the theca of the preovulatory ovarian follicle of the domestic fowl (Gallus domesticus). J Reprod Fertil 50, 179–181. https://doi.org/10.1530/jrf.0.0500179 (1977).

Kramer, A. E., Ellwood, K. M., Brannick, E. M. & Dutta, A. Separation of Avian Preovulatory Follicle Granulosa and Theca Cell Layers for Downstream Applications. J Vis Exp (212), https://doi.org/10.3791/67344 (2024).

Brady, K., Porter, T. E., Liu, H. C. & Long, J. A. Characterization of the hypothalamo-pituitary-gonadal axis in low and high egg producing turkey hens. Poult Sci 99, 1163–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2019.12.028 (2020).

Li, C. et al. The adiponectin receptor agonist, AdipoRon, promotes reproductive hormone secretion and gonadal development via the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in chickens. Poult Sci 102, 102319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2022.102319 (2023).

Zhao, J. et al. Interacting Networks of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Ovarian Axis Regulate Layer Hens Performance. Genes (Basel) 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14010141 (2023).

Chen, Q. et al. Expression dynamics of gonadotropin-releasing hormone-I and its mutual regulation with luteinizing hormone in chicken ovary and follicles. Gen Comp Endocrinol 270, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2018.10.011 (2019).

Diaz, F. J., Anthony, K. & Halfhill, A. N. Early avian follicular development is characterized by changes in transcripts involved in steroidogenesis, paracrine signaling and transcription. Mol Reprod Dev 78, 212–223. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrd.21288 (2011).

Wang, J. & Gong, Y. Transcription of CYP19A1 is directly regulated by SF-1 in the theca cells of ovary follicles in chicken. Gen Comp Endocrinol 247, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2017.03.013 (2017).

Zhu, G., Mao, Y., Zhou, W. & Jiang, Y. Dynamic Changes in the Follicular Transcriptome and Promoter DNA Methylation Pattern of Steroidogenic Genes in Chicken Follicles throughout the Ovulation Cycle. PLoS One 10, e0146028. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146028 (2015).

Zhu, G. et al. Transcriptomic Diversification of Granulosa Cells during Follicular Development in Chicken. Sci Rep 9, 5462. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41132-1 (2019).

Heidarzadehpilehrood, R. et al. A Review on CYP11A1, CYP17A1, and CYP19A1 Polymorphism Studies: Candidate Susceptibility Genes for Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and Infertility. Genes (Basel) 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13020302 (2022).

Aytes, A. et al. Cross-species regulatory network analysis identifies a synergistic interaction between FOXM1 and CENPF that drives prostate cancer malignancy. Cancer Cell 25, 638–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.017 (2014).

Lefebvre, C. et al. A human B-cell interactome identifies MYB and FOXM1 as master regulators of proliferation in germinal centers. Mol Syst Biol 6, 377. https://doi.org/10.1038/msb.2010.31 (2010).

Lachmann, A., Giorgi, F. M., Lopez, G. & Califano, A. ARACNe-AP: gene network reverse engineering through adaptive partitioning inference of mutual information. Bioinformatics 32, 2233–2235. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw216 (2016).

Margolin, A. A. et al. ARACNE: an algorithm for the reconstruction of gene regulatory networks in a mammalian cellular context. BMC Bioinformatics 7 Suppl 1, S7, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-7-S1-S7 (2006).

Chen, Q. et al. Transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of ovarian follicles reveal the role of VLDLR in chicken follicle selection. BMC Genomics 21, 486. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-020-06855-w (2020).

Hrabia, A., Wolak, D. & Sechman, A. Response of the matrix metalloproteinase system of the chicken ovary to prolactin treatment. Theriogenology 169, 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2021.04.002 (2021).

Huang, X. et al. Ovarian Transcriptomic Analysis of Ninghai Indigenous Chickens at Different Egg-Laying Periods. Genes (Basel) 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13040595 (2022).

Li, J. et al. Identification of the Key microRNAs and miRNA-mRNA Interaction Networks during the Ovarian Development of Hens. Animals (Basel) 10, https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10091680 (2020).

Wang, W. et al. Dynamic Changes in the Global MicroRNAome and Transcriptome Identify Key Nodes Associated With Ovarian Development in Chickens. Front Genet 9, 491. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2018.00491 (2018).

Yu, C. et al. Whole transcriptome analysis reveals the key genes and noncoding RNAs related to follicular atresia in broilers. Anim Biotechnol 34, 3144–3153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10495398.2022.2136680 (2023).

Guo, R., Chen, F. & Shi, Z. Suppression of Notch Signaling Stimulates Progesterone Synthesis by Enhancing the Expression of NR5A2 and NR2F2 in Porcine Granulosa Cells. Genes (Basel) 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11020120 (2020).

Huang, L. et al. CLOCK inhibits the proliferation of porcine ovarian granulosa cells by targeting ASB9. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 14, 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40104-023-00884-7 (2023).

Dansou, D. M. et al. Carotenoid enrichment in eggs: From biochemistry perspective. Anim Nutr 14, 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aninu.2023.05.012 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Dynamic Expression Profile of Follicles at Different Stages in High- and Low-Production Laying Hens. Genes (Basel) 15, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes15010040 (2023).

Han, Q. et al. Effects of FOXO1 on the proliferation and cell cycle-, apoptosis- and steroidogenesis-related genes expression in sheep granulosa cells. Anim Reprod Sci 221, 106604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anireprosci.2020.106604 (2020).

Herndon, M. K., Law, N. C., Donaubauer, E. M., Kyriss, B. & Hunzicker-Dunn, M. Forkhead box O member FOXO1 regulates the majority of follicle-stimulating hormone responsive genes in ovarian granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 434, 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2016.06.020 (2016).

Kong, C. et al. Signaling pathways of Periplaneta americana peptide resist H(2)O(2)-induced apoptosis in pig-ovary granulosa cells through FoxO1. Theriogenology 183, 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.theriogenology.2022.02.004 (2022).

Lin, S. Y., Morrison, J. R., Phillips, D. J. & de Kretser, D. M. Regulation of ovarian function by the TGF-beta superfamily and follistatin. Reproduction 126, 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1530/rep.0.1260133 (2003).

Nakamura, T. et al. Activin-binding protein from rat ovary is follistatin. Science 247, 836–838. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2106159 (1990).

Ling, S. et al. Epidemiologic and genetic associations of female reproductive disorders with depression or dysthymia: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 14, 5984. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55993-8 (2024).

Rabaglino, M. B. & Conrad, K. P. Evidence for shared molecular pathways of dysregulated decidualization in preeclampsia and endometrial disorders revealed by microarray data integration. FASEB J 33, 11682–11695. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.201900662R (2019).

Bai, K. et al. Melatonin alleviates ovarian function damage and oxidative stress induced by dexamethasone in the laying hens through FOXO1 signaling pathway. Poult Sci 102, 102745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.102745 (2023).

Zhou, L. et al. Oxidized Oils and Oxidized Proteins Induce Apoptosis in Granulosa Cells by Increasing Oxidative Stress in Ovaries of Laying Hens. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2685310. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/2685310 (2020).

Zhou, S., Zhao, A., Wu, Y., Mi, Y. & Zhang, C. Protective Effect of Grape Seed Proanthocyanidins on Oxidative Damage of Chicken Follicular Granulosa Cells by Inhibiting FoxO1-Mediated Autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biol 10, 762228. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.762228 (2022).

Liu, Z., Castrillon, D. H., Zhou, W. & Richards, J. S. FOXO1/3 depletion in granulosa cells alters follicle growth, death and regulation of pituitary FSH. Mol Endocrinol 27, 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2012-1296 (2013).

Thackray, V. G. Fox tales: regulation of gonadotropin gene expression by forkhead transcription factors. Mol Cell Endocrinol 385, 62–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2013.09.034 (2014).

Yang, M. et al. Corticosterone triggers anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects, and downregulates the ACVR1-SMAD1-ID3 cascade in chicken ovarian prehierarchical, but not preovulatory granulosa cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 552, 111675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2022.111675 (2022).

Luu, T. T. et al. FOXO1 and FOXO3 Cooperatively Regulate Innate Lymphoid Cell Development. Front Immunol 13, 854312. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.854312 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. PAX3-FOXO1 coordinates enhancer architecture, eRNA transcription, and RNA polymerase pause release at select gene targets. Mol Cell 82, 4428–4442 e4427, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2022.10.025 (2022).

Dong, J. T. & Chen, C. Essential role of KLF5 transcription factor in cell proliferation and differentiation and its implications for human diseases. Cell Mol Life Sci 66, 2691–2706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-009-0045-z (2009).

Kyriazis, I. D. et al. KLF5 Is Induced by FOXO1 and Causes Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res 128, 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316738 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Identification of a KLF5-dependent program and drug development for skeletal muscle atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2102895118 (2021).

Cui, C. et al. FOXO3 Is Expressed in Ovarian Tissues and Acts as an Apoptosis Initiator in Granulosa Cells of Chickens. Biomed Res Int 2019, 6902906. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6902906 (2019).

Shen, M. et al. Involvement of FoxO1 in the effects of follicle-stimulating hormone on inhibition of apoptosis in mouse granulosa cells. Cell Death Dis 5, e1475. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.400 (2014).

Makker, A., Goel, M. M. & Mahdi, A. A. PI3K/PTEN/Akt and TSC/mTOR signaling pathways, ovarian dysfunction, and infertility: an update. J Mol Endocrinol 53, R103-118. https://doi.org/10.1530/JME-14-0220 (2014).

Liu, Z. et al. FSH and FOXO1 regulate genes in the sterol/steroid and lipid biosynthetic pathways in granulosa cells. Mol Endocrinol 23, 649–661. https://doi.org/10.1210/me.2008-0412 (2009).

Brosens, J. J., Wilson, M. S. & Lam, E. W. FOXO transcription factors: from cell fate decisions to regulation of human female reproduction. Adv Exp Med Biol 665, 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1599-3_17 (2009).

Koch, S. Regulation of Wnt Signaling by FOX Transcription Factors in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13143446 (2021).

Ling, J. et al. FOXO1-regulated lncRNA LINC01197 inhibits pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell proliferation by restraining Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 38, 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13046-019-1174-3 (2019).

Manuylov, N. L., Smagulova, F. O., Leach, L. & Tevosian, S. G. Ovarian development in mice requires the GATA4-FOG2 transcription complex. Development 135, 3731–3743. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.024653 (2008).

Nicol, B. et al. Follistatin is an early player in rainbow trout ovarian differentiation and is both colocalized with aromatase and regulated by the wnt pathway. Sex Dev 7, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1159/000350687 (2013).

Davis, A. J. & Johnson, P. A. Expression pattern of messenger ribonucleic acid for follistatin and the inhibin/activin subunits during follicular and testicular development in gallus domesticus. Biol Reprod 59, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1095/biolreprod59.2.271 (1998).

Chen, R. et al. Immuno-Neutralization of Follistatin Bioactivity Enhances the Developmental Potential of Ovarian Pre-hierarchical Follicles in Yangzhou Geese. Animals (Basel) 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12172275 (2022).

Sinner, D. et al. Sox17 and Sox4 differentially regulate beta-catenin/T-cell factor activity and proliferation of colon carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol 27, 7802–7815. https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.02179-06 (2007).

Tan, D. S., Holzner, M., Weng, M., Srivastava, Y. & Jauch, R. SOX17 in cellular reprogramming and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 67, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.008 (2020).

Nakao, N. et al. Circadian clock gene regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression in preovulatory ovarian follicles. Endocrinology 148, 3031–3038. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2007-0044 (2007).

Liu, Y. et al. Loss of BMAL1 in ovarian steroidogenic cells results in implantation failure in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 14295–14300. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1209249111 (2014).

Chen, R. et al. Circadian clock gene BMAL1 regulates STAR expression in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. Poult Sci 102, 103159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2023.103159 (2023).

Tischkau, S. A., Howell, R. E., Hickok, J. R., Krager, S. L. & Bahr, J. M. The luteinizing hormone surge regulates circadian clock gene expression in the chicken ovary. Chronobiol Int 28, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.3109/07420528.2010.530363 (2011).

Kramer, A. E. et al. Transcriptomic data reveals MYC as an upstream regulator in laying hen follicular recruitment. Poultry Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psj.2024.104547 (2024).

Papachristodoulou, A. et al. Metformin Overcomes the Consequences of NKX3.1 Loss to Suppress Prostate Cancer Progression. Eur Urol 85 (4), 361–372, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2023.07.016 (2024).

Kukurba, K. R. & Montgomery, S. B. RNA Sequencing and Analysis. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 951–969, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.top084970 (2015).

Sah, N. et al. RNA sequencing-based analysis of the laying hen uterus revealed the novel genes and biological pathways involved in the eggshell biomineralization. Sci Rep 8, 16853. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35203-y (2018).

Wang, Z., Gerstein, M. & Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet 10, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg2484 (2009).

Johnson, P. A. Follicle selection in the avian ovary. Reprod Domest Anim 47(Suppl 4), 283–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.02087.x (2012).

Griffin, A. T., Vlahos, L. J., Chiuzan, C. & Califano, A. NaRnEA: An Information Theoretic Framework for Gene Set Analysis. Entropy (Basel) 25, https://doi.org/10.3390/e25030542 (2023).

Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J. & Smyth, G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 26, 139–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 (2010).

Alvarez, M. J. et al. Functional characterization of somatic mutations in cancer using network-based inference of protein activity. Nat Genet 48, 838–847. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3593 (2016).

Goeman, J. J., van de Geer, S. A., de Kort, F. & van Houwelingen, H. C. A global test for groups of genes: testing association with a clinical outcome. Bioinformatics 20, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btg382 (2004).

Schmittgen, T. D. & Livak, K. J. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3, 1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2008.73 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Milos Markis for helpful discussions on animal husbandry, Mark Parcells for animal vaccinations, and Behnam Abasht for broiler breeder samples. Figure 1 was created using BioRender.com using an institutional license sponsored by the University of Delaware Research Office. This work was supported by the UD Delaware Biotechnology Institute Sequencing and Genotyping Center and the CUIMC JP Sulzberger Columbia Genome Center. AEK was supported, in part, by the UD CANR Unique Strengths PhD Fellowship and by a travel award from the National Science Foundation Animal Genome to Phenome Research Coordination Network [Award IOS-1456942]. KME is supported by USDA NIFA grant 2023-67011-40333. This work was supported by grants from DE-CTR ACCEL, an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number U54-GM104941 and the State of Delaware, and NSF DMS-2413833 to SD; Spanish Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCiii, Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities) research grants PI22/00877 and IMPaCT-DATA ref. IMP/00019 to JDLR; and the University of Delaware Research Foundation (UDRF) and the Delaware INBRE program (supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences – NIGMS P20 GM103446 from the National Institutes of Health and the State of Delaware) to AD.

Funding

National Science Foundation,IOS-1456942,DMS-2413833,University of Delaware,CANR Unique Strengths,National Institute of Food and Agriculture,2023-67011-40333,Delaware-CTR ACCEL Program,U54-GM104941,Instituto de Salud Carlos III,PI22/00877,University of Delaware Research Foundation,Delaware IDeA Network of Biomedical Research Excellence,P20 GM103446

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AEK took the lead in drafting and writing the manuscript, carried out animal, molecular biology, and bioinformatics experiments, contributed to interpretation of the results, revised, and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. ABG carried out bioinformatics experiments, contributed to interpretation of the results, revised, and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. KME contributed to animal and molecular biology experiments and revised the manuscript for content and clarity. SD contributed to bioinformatics approaches, statistical analysis, and revised the manuscript for content and clarity. JDLR provided advisory guidance and bioinformatics training, contributed to interpretation of the results, revised, and edited the manuscript for intellectual content. AD conceived the study, designed and planned the experiments, procured funding support, provided advisory guidance and molecular biology laboratory training, contributed to interpretation of the results, revised, and edited the manuscript for intellectual content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All animal research reported in this manuscript are as per ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kramer, A.E., Berral-González, A., Ellwood, K.M. et al. Cross-species regulatory network analysis identifies FOXO1 as a driver of ovarian follicular recruitment. Sci Rep 14, 30787 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80003-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80003-2