Abstract

Due to the unique geographical environment of the plateau, large-scale damage and destruction of fractured surrounding rock often occur during geotechnical engineering construction as a result of high-temperature cycles. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the mechanical properties and damage characteristics of fractured granite under the influence of cyclic temperature, uniaxial compression tests were conducted on granite specimens with pre-existing fractures at cyclic temperatures of 30 °C, 50 °C, 70 °C, 100 °C, and 130 °C. The study integrated analyses of characteristic stress, acoustic emission parameters, damage variables, fractal dimensions, and SEM to explore the mechanical properties and damage features of granite. The results indicated that at a 45° fracture inclination and a temperature of 70 °C, granite exhibited a distinct turning point in mechanical properties and damage characteristics. At the same cyclic temperature, granite with a 45° pre-existing fracture showed significant decreases in peak stress, elastic modulus, and σci/σm ratios, with the AE b-value drop point noticeably earlier, and both cumulative AE ring count and total energy reduced. The damage variable quickly reached its maximum, and the development of internal microcracks in the specimen is highly orderly. At the same fracture inclination, peak stress, elastic modulus, and σci/σm slightly increased at 70 °C, while AE ring counts and total energy were lower, indicating the degree of internal thermal damage in the specimen has significantly decreased, and the development of internal microcracks in the specimen has shown a marked reduction in orderliness. These findings provide theoretical insight into the meso-damage and failure mechanisms of granite influenced by different cyclic temperatures and fracture inclinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

In recent years, high temperatures have become an increasingly prominent challenge in tunnel engineering. For instance, the Sangzhuling Tunnel reaches a peak temperature of 89 °C, Nigge Tunnel up to 70 °C, Heibai Water Tunnel 60 °C, and Bayu Tunnel 47 °C1,2,3. Extended exposure to high temperatures poses risks to both worker health and equipment maintenance, necessitating continuous cooling. However, repetitive heating and cooling accelerate the deterioration of rocks with natural fractures, leading to extensive cracking and instability of surrounding rock, posing engineering hazards. Thus, understanding the changes in mechanical properties, damage, and instability behaviors of cracked granite under cyclic temperature conditions is crucial for safe tunnel construction.

Numerous studies have been conducted both domestically and internationally on the impact of cyclic temperature on rock. Li et al. conducted Brazilian splitting tests on granite subjected to cyclic temperatures ranging from 100 °C to 700 °C, finding that the mechanical properties of granite decline continuously as the temperature increases4. Yang et al. performed uniaxial compression tests on granite subjected to cyclic heating and water cooling, discovering that the mechanical properties of the specimens improve to some extent at 50 °C and 150 °C5. Other researchers have explained the changes in the mechanical properties of rocks under cyclic temperature from the perspective of internal structural and chemical changes. For example, Yang studied the impact of thermal-cold shocks at 600 °C on rock porosity, finding that pores in the rock develop severely and form clusters under these conditions6. Kumari conducted thermal shock tests on granite and found that the minerals inside the granite undergo phase transitions at 573 °C7. These studies indicate that the effect of cyclic temperature on the mechanical properties of rock is not linear and significantly impacts the internal structure and chemical properties of the rock. In studies on the impact of cyclic temperature on rock damage, Xia et al. confirmed through temperature cycling tests that the damage caused by cyclic temperature on rocks is irreversible and cumulative8. Zhu et al. observed macrocracks, expansion, and penetration in granite through SEM analysis at temperatures exceeding 300 °C9. Jia et al. found that the failure mode of granite shifts from tensile-shear failure to tensile failure as the temperature increases from 200 °C to 400 °C10. These findings suggest that rock damage after cyclic temperature is irreversible and that the failure mode changes. In research on the effects of repeated temperature cycling on cracked rocks, Wang et al. used acoustic emission to study the impact of different crack angles on rock damage, finding that damage is greater at a 45° crack angle, with a significant decrease in mechanical properties11. Song et al. studied freeze-thaw cycling in double-crack rocks and discovered that initial damage decreases as the crack angle increases, but damage grows rapidly in the later stages of compression12. Wang et al. used numerical simulations to study granite with triangular cracks under high temperatures, finding that thermal stress is concentrated around the prefabricated cracks, and thermal stress fields become uneven13. Li et al. studied the impact of thermal cycling on cracked rocks, finding that the damage area of cracked rocks is smaller than that of intact rocks after thermal cycling14.These studies have primarily focused on mineral decomposition, changes in physical and mechanical properties, the impact of crack angle, and crack development characteristics. However, most of the temperatures studied have been above 100 °C, while in current high-temperature tunnel excavations, the issue is the large-scale damage to surrounding rock caused by repeated cooling and heating cycles within 100 °C. There are few reports on the changes in mechanical properties and damage characteristics of cracked rocks under cyclic temperatures between 30 °C and 100 °C.

Therefore, considering the actual engineering hazards such as rock bursts and block fractures caused by temperature fluctuations in high-temperature tunnels like Sangzhuling and Bayu, this study performed uniaxial compression tests on granite with fractures under cyclic temperatures to study the changes in the mechanical properties of granite and the damage characteristics during the loading process. The findings offer theoretical support and references for controlling the stability of surrounding rock and designing support structures under cyclic thermal conditions.

Experimental equipment and procedure

The experimental equipment mainly consists of a loading system, an acoustic emission system, and a strain analyzer, as shown in Fig. 1. The loading system uses a TWA-2000 kN rock triaxial mechanical testing system, with a maximum pressure of 2000 kN, capable of directly measuring the axial stress-strain during the compression process, as shown in Fig. 1j. The SENSOR acoustic emission system accurately measures various acoustic emission parameters, as shown in Fig. 1g. The strain analyzer has a measurement range of ± 50,000 µε, with a strain indication error of no more than 0.2% ± 2 µε, as shown in Fig. 1f.

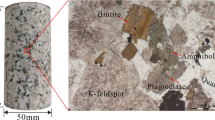

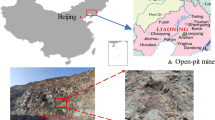

Granite samples sourced from the Sangzhuling Tunnel were prepared into cylindrical specimens of ø50 mm × 100 mm by drilling and polishing. Cracks were created on the specimen surfaces using a cutter, with careful alignment by marking the cutting position and entering precise measurements. The crack angles (measured from the horizontal direction) were set at 0°, 45°, and 90°, with a depth of 4 mm, length of 50 mm, and width of 1 mm, as shown in Fig. 1a. Given that temperatures in high-temperature tunnels can reach up to 89 °C, cyclic heating was conducted at maximum temperatures of 30 °C, 50 °C, 70 °C, 100 °C, and 130 °C, followed by cooling to 15 °C. Each temperature cycle was repeated five times. The detailed experimental procedure is as follows:

(1)Cyclic Heating-Cooling Test: Before heating, the specimen was wrapped in a.

high-temperature waterproof bag to ensure that water does not affect the specimen during the temperature cycle, as shown in Fig. 1b. The specimen was then heated in an electric blast drying oven for 24 h to ensure uniform heating, as shown in Fig. 1c. After heating, the specimen was cooled in a constant temperature refrigerator (15 °C) for 4 h, and its temperature was monitored with a temperature gun to ensure complete cooling. To ensure waterproofing, the high-temperature waterproof bag was replaced before each cycle, and the above steps were repeated until the required number of cycles was reached.

(2)Uniaxial Compression Test: The uniaxial compression was performed using a displacement loading method with an axial stress loading rate of 0.01 mm/s. During the compression process, the acoustic emission system and strain analyzer were used to monitor rock damage and deformation. Six acoustic emission probes were selected, distributed in two groups at the upper and lower ends of the specimen, each group placed approximately 20 mm from the end. The upper probes were arranged at 0°, 90°, and 180°, while the lower probes were arranged at 180°, 270°, and 360° to enhance signal strength and improve accuracy, as shown in Fig. 1h. In the strain analysis system, strain gauges were attached laterally to the middle of the specimen, approximately 50 mm from both ends, to monitor lateral strain during compression, as shown in Fig. 1e.

Mechanical properties of cracked granite under temperature cycles

The stability of the surrounding rock is closely related to the physical and mechanical properties of the rock. After five temperature cycles, the mechanical properties of granite specimens with different crack angles and cycle temperatures are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

From Fig. 2, it is evident that after five temperature cycles, both the peak strength and elastic modulus of the rock samples initially decrease, then increase, and finally decrease again with the rise in temperature. The average peak strength values are 183.51 MPa, 161.10 MPa, 169.78 MPa, 157.43 MPa, and 111.17 MPa, respectively, while the average elastic modulus values are 33.40 GPa, 27.22 GPa, 28.56 GPa, 23.23 GPa, and 16.76 GPa, respectively. Between 30 °C and 70 °C, the peak strength and elastic modulus of granite fluctuate, and beyond 70 °C, both parameters rapidly decline. Although the peak strength and elastic modulus of cracked granite exhibit slight fluctuations with temperature increase, the overall trend shows a decrease.

Figure 3 indicates that as the crack angle increases, the average peak strength and elastic modulus of granite under different cycle temperatures show a trend of initial decrease followed by an increase. The average peak strength values are 163.7 MPa, 153.01 MPa, and 153.09 MPa, while the average elastic modulus values are 28.35 GPa, 23.68 GPa, and 25.47 GPa, respectively. The peak stress and elastic modulus reach their minimum values at a 45° crack angle. This is because the rock specimens with a prefabricated 45° crack predominantly exhibit compressive-shear failure, whereas those with a 90° prefabricated crack mainly undergo tensile failure (refer to Sect. 5.2 for failure modes). The difference in failure modes results in the regular variation of peak strength and elastic modulus. Overall, the ability of granite to resist deformation weakens with the increase in cycle temperature, its ductility increases, and as the prefabricated crack angle increases, the ability to resist deformation and ductility first weakens (weakest at 45°) and then increases.

Damage characteristics of granite under cyclic temperature

Analysis of stress characteristic point variations

While peak stress and elastic modulus can reflect the stability of the surrounding rock during engineering excavation, they cannot characterize the internal damage and microstructural changes within the rock. Therefore, by studying the stress damage thresholds (stress characteristic points) at each stage of rock compression, the internal damage and microstructural characteristics of granite under the influence of cyclic temperature and cracks can be determined.

Currently, methods for calculating the stress cracking point include the volumetric strain method15, acoustic emission method16, lateral strain difference method17, and dissipated energy rate method18. Most scholars believe that the energy generated during the compression of rock is directly related to its deformation and failure19. Therefore, when determining stress characteristic points, the point at which the elastic energy rate reaches its maximum under axial pressure is defined as the closure stress (σcc). Afterward, as axial pressure continues to increase, the rock enters a period of calm crack development, where the dissipated energy decreases linearly. The end of this linear development of dissipated energy is defined as the crack initiation stress (σci)20. After this, the cracks within the rock enter an unstable stage, and the proportion of dissipated energy increases. When damage fully develops, the dissipated energy rate reaches a minimum, thereby determining the damage stress (σcd)21. As can be seen from the above analysis, from the perspective of energy dissipation, the evolution of cracks and determination of stress characteristics have a solid theoretical background. Therefore, the dissipated energy rate method is selected to calculate the characteristic stress points, which allows for accurate determination of these points during the compression of rock specimens22. The specific calculation method and determination of characteristic points are as follows:

The total energy of the rock can be calculated using the following expression:

Where U0 is the total energy generated by the failure of rock per unit volume (kJ·m−3); Ue is the elastic energy (kJ·m−3); Ud is the dissipated energy (kJ·m−3); σ1i and σ1i−1 are the stresses at the time of collection (MPa); ε1i and ε1i−1 are the axial strains at the time of collection; and i is the collection sequence.

The elastic energy Ue in Eq. (1) can be calculated using the following formula:

Where σ1 is the principal stress (MPa); and E0 is the initial elastic modulus (GPa).

The dissipated energy Ud generated by rock compression in Eq. (1) can be calculated using the following formula:

An example of the determination of characteristic stress points using dissipated energy is shown in Fig. 4.

Characteristic stress points are thresholds in the development stage of rock damage. The ratio of characteristic stress to peak stress can indicate the extent of internal damage in the rock. The larger the ratio, the greater the proportion of total damage at that stress threshold. The ratio of closure stress to peak stress σcc/σmrepresents the development extent of pore closure during rock compression23. The ratio of crack initiation stress to peak stress σci/σmis significantly affected by internal defects and can serve as a criterion for rock integrity24. The ratio of damage stress to peak stress σcd/σmdirectly reflects the long-term strength of the rock and indicates the stage where cracks within the rock enter instability25. The experimental results of characteristic stress and the ratio of characteristic stress to peak stress under temperature cycles are shown in Table 1; Fig. 5.

From Fig. 5a, it is observed that the σcc/σm of cracked granite specimens decreases first and then increases with temperature rise for the same crack angle. The fluctuation range of σcc/σm with crack angle variation is within 2%, indicating that temperature has a significant effect on σcc/σm, while the crack angle has a minimal impact. Figure 5b shows that σci/σm of cracked granite increases first and then decreases with temperature rise for the same crack angle, with a maximum at 70 °C. At the same temperature, σci/σm decreases first and then increases with the increase of crack angle, with a larger fluctuation at a 0° crack angle, with variation values of 15.46% and 12.33%. Figure 5c shows that while temperature and crack angle affect the σcd/σm of cracked granite, the pattern is not evident, with a variation range of about 3% σm. This is because σcc/σm, σci/σm, and σcd/σm are significantly influenced by internal pores, prefabricated cracks, natural cracks, the overall structure, and chemical properties of the rock. The inclination angle of cracks significantly impacts the development and initiation of internal cracks in granite, while cyclic temperature primarily affects the initiation of internal pores and cracks within the granite.

Analysis of acoustic emission parameters

The variation trends of rock mechanical properties can qualitatively describe the influence of internal rock defects on damage and failure, but it’s challenging to quantify crack numbers and their development intensity under compression. Acoustic emission (AE) ringing counts indicate changes in crack quantity during loading, while AE energy describes crack propagation extent. Additionally, fluctuations in the AE b-value directly reflect the degree of internal damage progression26,27. The last significant drop in b-value before peak stress serves as a characteristic parameter signaling imminent rock failure28, where a lower b-value indicates more intense microcrack development. Therefore, incorporating AE ringing, AE energy, and AE b-value analysis facilitates studying the damage evolution within the rock. The b-value formula is as follows:

In the equation, M represents the magnitude, which is calculated as the amplitude of acoustic emission divided by 20. N denotes the number of occurrences within the range of M, typically representing the number of impacts exceeding the acoustic emission amplitude. a is a constant, usually defined based on the type of rock, and b is the ratio of small amplitude events to large amplitude events28.

After cyclic temperature effects, the changes in acoustic emission ringing, energy, b-value, and stress-strain curves during the compression process of granite specimens with different crack angles are shown in Fig. 6. The characteristic stress points and b-value drop points in the rock compression process are marked. In Fig. 6a, 66% σm represents the stress percentage at the point where the acoustic emission b-value drops, and “30 − 0” means the specimen temperature is 30 °C with a crack angle of 0°. The other numbers in the figures have similar meanings.

From Fig. 6, it can be seen that under different temperatures, the magnitude of the acoustic emission b-value first increases and then decreases with the increase of the crack angle. There is no significant change in the b-value during the 0-σcc stage, while during the σcc-σci stage, the b-value rises continuously and reaches its maximum, indicating that a large number of microcracks appear inside the rock in this stage, but the degree of crack development and penetration is low. When the specimen enters the σci-σm stage, the b-value fluctuates and decreases, indicating that microcracks develop rapidly until macroscopic cracks form, leading to complete rock failure and the b-value reaching its minimum. At the same temperature, as the crack angle increases, the average b-value drop point decreases from 80% σm (0° prefabricated crack) to 60% σm (45° prefabricated crack) and then increases to 75% σm (90° prefabricated crack), with fluctuations in the b-value drop point. This indicates that the prefabricated cracks influence and guide the development of internal cracks in the rock, significantly enhancing the intensity of internal damage development and leading to the early formation of large-scale cracks. At the same crack angle, with the increase of temperature, the b-value sudden drop point of 90° prefabricated cracks increases and then decreases, while the b-value sudden drop point of 45° prefabricated cracks decreases and then increases, and the b-value sudden drop point of 0° prefabricated cracks continues to increase, so there is not a uniform development pattern of granite at the three angles with the increase of temperature, which suggests that there is no obvious pattern of the influence of the temperature on the formation of the large-scale cracks inside the specimens.

Furthermore, Fig. 6 illustrates that at temperatures of 30 °C, 50 °C, and 70 °C, the acoustic emission ringing and energy distribution for each crack angle advance significantly with increasing temperature. At 100 °C and 130 °C, the acoustic emission ringing and energy distribution for the 0° crack initially delay and then advance with rising temperature. In contrast, for the 45° and 90° cracks, these parameters consistently delay with increasing temperature, with the 90° crack showing a significant delay. This indicates that temperature has a considerable impact on the pores and natural cracks within the rock, affecting the distribution of acoustic emission ringing and energy during the early stages of compression, and that crack angle can guide the development of internal cracks. Therefore, both temperature and crack angle have significant effects on the distribution of acoustic emission ringing and energy in the specimen.

To quantitatively analyze the variation pattern of acoustic emission parameters under the influence of cyclic temperature and crack angle, the trends in cumulative ringing count and total energy of granite with cracks under the influence of temperature and crack angle are shown in Fig. 7.

From Fig. 7, it can be seen that with increasing cyclic temperature, the cumulative ringing count and total energy of granite with cracks first increase, then decrease, and increase again, reaching a minimum at 70 °C. At the same temperature, the cumulative ringing count and total energy of acoustic emission first decrease and then increase with increasing crack angle, with a minimum at 45°. The above analysis shows that under the same temperature, the cumulative ringing count and total energy of the specimen with a 45° crack angle are the smallest, indicating that the 45° crack angle facilitates the guidance of rock damage and failure. The internal microcracks in the rock quickly merge to form large cracks, while the guidance of internal crack development is significantly reduced in specimens with 0° and 90° cracks. As a result, large-scale cracks cannot form quickly, leading to better crack development and a significant increase in cumulative ringing count and total energy.

Analysis of damage development characteristics

The acoustic emission b-value, cumulative ringing, total energy, and energy distribution can indicate the intensity, total amount, and distribution of damage influenced by cyclic temperature and prefabricated cracks. However, a quantitative analysis of the damage development process during the compression of rocks is still lacking. Therefore, a damage variable is introduced to further quantitatively analyze the damage development characteristics of granite with cracks under cyclic temperature. The sudden increase in the damage variable represents the large-scale initiation of microcracks inside the specimen29.

The damage variable can be defined as:

Where Nd represents the cumulative ringing count of acoustic emission at time d from the start of the axial compression test, and Nm represents the cumulative ringing count of acoustic emission at the end of the axial compression test. Based on the above calculation, the damage variables of granite under cyclic temperature and crack angle were calculated, and the results are shown in Fig. 8. In Fig. 8a, “30 –0” indicates that the specimen temperature is 30 °C and the crack angle is 0°, with the same meaning for the other values.

Figure 8 analysis shows that under all conditions, the damage variable of specimens follows a pattern of slow progression, rapid increase, and eventual stabilization. During the 0-σci phase, no significant change in the damage variable is observed. In the σcc-σci phase at 70 °C, the damage variable accelerates, signifying a rapid increase in internal microcracks and early development of specimen damage. The σci-σm phase shows a sharp rise in the damage variable, indicating the initiation, propagation, and accumulation of microcracks until reaching σm, where the damage variable approaches its maximum value of 1, with macrocrack penetration leading to specimen instability and failure. At the same temperature, the 45° pre-cracked granite specimen exhibits an earlier damage variable surge. When stress reaches σcd, the 45° pre-cracked specimen’s damage variable exceeds 0.8, developing rapidly in the σci-σcdphase. This rapid development is because microcracks in pre-cracked specimens primarily propagate from the crack tip and extend outward at an angle, this leads to the easier connection of local cracks generated during the compression process of rocks under 45° cracks, which facilitating the formation of large tensile-shear macroscopic cracks30,31. Consequently, the 45° crack significantly influences damage evolution in the σci-σm phase, markedly enhancing microcrack guidance in the specimen.

To further analyze the damage proportion in each characteristic stress stage under the influence of cyclic temperature and crack angle, the trend of damage proportion in each characteristic stress stage of granite under the influence of cyclic temperature and crack angle is shown in Fig. 9.

From Fig. 9, it can be seen that under cyclic temperatures of 30 °C and 50 °C and different prefabricated crack angles, the maximum damage proportion is almost entirely concentrated in the σci-σcd stage, indicating that at these temperatures, the internal microcracks of the granite specimen initiate and expand rapidly from the crack initiation stress to the damage stress stage, leading to accelerated specimen damage. However, after the cyclic temperature exceeds 70 °C, the damage proportion begins to show dispersed distribution, and the higher the temperature, the greater the dispersion of the damage proportion, indicating that the thermal damage effect inside the specimen becomes more evident after 70 °C. This conclusion is consistent with that of Sect. 4.1.

Analysis of damage fractal characteristics

Fractal dimension, as a mathematical tool for analyzing irregular objects, can quantitatively describe irregular objects to reveal their intrinsic relationships. The crack development process during rock compression follows a nonlinear pattern with regularity. To describe the intrinsic relationships of this nonlinear process, the fractal dimension can be used for analysis.

To further analyze the damage distribution during the granite specimen’s damage development process, the correlation dimension of the acoustic emission ringing count is introduced to characterize the chaos degree of the damage distribution within the rock32,33. This approach is used to explore the influence of cyclic temperature and crack inclination on the damage distribution and development patterns within the rock at various stages. The correlation dimension calculation considers the acoustic emission ringing counts of granite specimens under compression during four stages: 0-σcc, σcc-σci, σci-σcd, and σcd-σm, with each stress stage being treated as a separate time window for analysis, leading to the calculation of the fractal dimension Df.The calculation method is as follows:

The G-P correlation dimension is determined by first constructing a phase space using a sample of acoustic emission ringing counts n and forming an m-dimensional space (m < n ) as follows:

Where the first vector X1 is created by taking the first m elements of the time series of the ringing counts. A phase space of dimension m is then constructed by sequentially selecting elements at intervals, leading to N = n - m + 1 vectors:

The G-P function is then defined as:

Where C is the correlation function, H is the Heaviside function, and r is a scale factor. The correlation dimension Df is then given by:

The equation includes the observational coefficient k, which is typically chosen between 10 and 20, to determine the value of r within a certain interval, thereby obtaining the correlation dimension Df. The expression for Df is as follows:

Based on the G-P correlation dimension model calculation described above, the computed data points {lnr, lnC} were linearly fitted. The closer the fit to a straight line, the more fractal characteristics the data set exhibits. In this study, each stress stage during the compression of the specimen was treated as an interval, and the minimum embedding dimension m = 1 was chosen for a single calculation. By fitting 15 {lnr, lnC} calculation points, the fitting interval of the data was determined to be between 93% and 99%, indicating that the ringing count of the granite specimen under the influence of temperature and crack angle exhibits fractal characteristics across the four stages of 0-σcc, σcc-σci, σcd-σm, σm-post-peak.

Using this model, the ringing counts under different stress stages were calculated for the granite specimens subjected to varying cyclic temperatures and crack inclinations. The results are shown in Fig. 10.

Analysis of Fig. 10, it is observed that under the same crack inclination, the correlation dimension Df exhibits a trend of first decreasing, then increasing, and finally decreasing again with increasing temperature. This indicates that the internal damage development in the rock initially becomes more ordered, then less ordered, and finally more ordered again, with the maximum correlation dimension occurring at 70 °C, which acts as a turning point for temperature. For the same temperature, the impact of crack inclination on the correlation dimension Df is not significant during the 0-σcc stage. However, during the σcc-σci,σci-σcd, and σcd-σm stages, the fluctuation in Df with increasing crack inclination decreases from 0.19 (0°) to 0.12 (45°) and then increases to 0.39 (90°).

This suggests that at 70 °C, the distribution of microcracks within the specimen is chaotic and disordered, unable to form a clear development trend. The fluctuations in Df during the σcc-σci,σci-σcd, and σcd-σm stages are more significant under 0° and 90° crack inclinations due to poor guidance of internal crack development, leading to dispersed damage development and less distinct crack growth paths.

Discussion

Damage mechanism under cyclic temperature

Cyclic temperature directly affects the microscopic physical properties of the rock, such as pores and microcracks. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used to further analyze the damage mechanism of granite under cyclic temperature. The granite specimens were subjected to cyclic temperatures of 30 °C, 50 °C, 70 °C, 100 °C, and 130 °C, and then slices were taken from the middle part of the specimens for SEM analysis. Given space limitations, only partial results for each specimen group are presented in Fig. 11, with micro-pores and microcracks marked. The SEM images reveal that internal pore and microcrack changes are not significant at 30 °C and 70 °C. However, at 50 °C, 100 °C, and 130 °C, the number of internal pores and microcracks increases significantly, indicating a marked increase in rock damage. This observation is consistent with the conclusions drawn earlier in Sect. 3.3 and 3.4.

To quantitatively analyze the SEM images under different temperatures, the images were binarized, and the box dimension was used to evaluate the surface roughness of the granite34. A higher box dimension DB indicates lower surface roughness, and vice versa. The calculation method is as follows:

In this formula: N(k) represents the number of boxes required to cover k; varepsilon εk is the length of the box’s edge. MATLAB software was used for grayscale processing, image filtering, feature detection, and boundary recognition of SEM images to obtain a binarized image by selecting an appropriate threshold.

Analysis of Fig. 12 shows that the box dimension DB decreases, then increases, and then decreases again with increasing temperature. This trend suggests that the changes in microcracks and micropores within the granite initially increase, then decrease, and then increase again with rising temperature, with a significant drop in the box dimension observed between 70 °C and 100 °C, indicating that the internal microcracks and micropores are most pronounced between these temperatures. Thus, 70 °C serves as a temperature turning point.

At 50 °C, the evaporation of free water, as well as strongly and weakly bound water, from the interior of granite specimens is relatively minimal, and the friction between crystalline particles inside the specimen is relatively low. Consequently, microcracks and pores are more susceptible to crystal thermal expansion, leading to a noticeable increase in internal microcracks and pores. As the temperature rises to 70 °C, further evaporation of free water, as well as strongly and weakly bound water occurs, significantly increasing friction between crystalline particles, which slightly enhances granite strength35,36, marking a turning point in mechanical properties. However, at temperatures exceeding 90 °C, a certain degree of microcrystalline fracture is within granite37,38,39,40, with intensified thermal expansion effects that further promote mineral crystal expansion, surface exfoliation, and visible development of pores and microcracks. As a result, thermal damage within granite intensifies, significantly degrading its mechanical properties.

Damage mechanism under crack inclination

The crack inclination has a guiding effect on the damage and failure of granite. To further analyze the impact of crack inclination on damage and failure, the failure patterns of granite specimens with different cyclic temperatures and crack inclinations were examined, as shown in Fig. 13.

The analysis of Fig. 13shows that the final failure modes of rocks with different crack inclinations at the same temperature are not the same. The failure mode under a 0° crack is dominated by tensile-shear failure, under a 45° crack by distinct shear failure, and under a 90° crack by tensile failure, with a significant reduction in shear failure development. Under a 45° crack, the final failure pattern retains better integrity, and the specimen is not completely pulverized after removing the protective film. This is because, during compression, the rock first develops along internal flaws41,42,43,44. Thus, the 45° crack guides the development of distinct diagonal cracks, leading to clear shear failure and rapid penetration of localized cracks. Therefore, the internal microcracks under a 45° crack are not fully developed, resulting in better integrity of the final failure pattern. This observation is consistent with the conclusions drawn earlier in Analysis of stress characteristic point variations, Analysis of acoustic emission parameters, and Analysis of damage fractal characteristics section.

Conclusion

-

1.

1. At the same cyclic temperature, the peak stress, elastic modulus, and σci/σm of granite initially decrease and then increase with the increase in crack inclination, reaching their minimum values at a crack inclination of 45°. At the same crack inclination, the peak stress, elastic modulus, σcc/σm, and σci/σm of granite initially decrease, then increase, and decrease again with increasing temperature, with 70 °C as the turning point.

-

2.

2. At the same cyclic temperature, the damage drop point occurs earlier at 45°, with the 45° prefabricated crack guiding the development of internal cracks in the rock. At the same crack inclination, the cumulative ring count and total energy of acoustic emissions are the lowest at 70 °C. indicating the minimal damage to the rock specimen. The temperature has no significant impact on the b-value drop point.

-

3.

3. At the same cyclic temperature, the rate of increase in the damage variable initially increases and then slows down with the increase in crack inclination. At the same crack inclination, the dispersion of damage proportion continuously increases with increasing temperature. Additionally, at a crack inclination of 45°, the fluctuation in fractal dimension is minimal, with strong orderliness and directionality in the development of internal microcracks. At 70 °C, the fractal dimension is at its maximum, with internal microcracks in the specimen becoming more dispersed.

-

4.

4. At a cyclic temperature of 70 °C, the number of internal microcracks and pores is relatively small. The crack inclination significantly influences the internal crack development trend in the specimen. As the crack inclination increases from 0° to 90°, the specimen’s failure mode transitions from tensile-shear failure (0°) to shear failure (45°) and tensile failure (90°). With increasing temperature, the internal microcracks and pores in the granite specimen initially increase, then decrease, and increase again, with the specimen’s damage following a similar trend, with 70 °C as the turning point.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Change history

14 January 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86301-7

References

Yan, J. et al. Inoculation and characters of rockbursts in extra-long and deep-lying tunnels located on Yarlung Zangbo suture. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 38(04), 769–781 (2019).

Yan, J. et al. Prediction of rock bursts for Sangzhuling tunnel located on Lhasa-Nyingchi railway under coupled thermo-mechanical effects. JSWJ 53(03), 434–441 (2018).

Duan, Z. F. et al. Potential estimation of hot dry rock geothermal resources in sedimentary basins: A case study from Jianhu Uplift, Subei Basin. J. China Univ. Pet. 48(01), 46–54 (2024).

Li, C. et al. Brazilian split characteristics and mechanical property evolution of granite after cyclic cooling at different temperatures. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 39(09), 1797–1807 (2020).

Yang, M. et al. Mechanical properties and failure modes of granite under the condition of cyclic heating and water-cooling. Sci. Tec. Eng. 21(32), 13828–13836 (2021).

Yang, X. X. et al. Fracture characteristics and pore connectivity of sandstone under thermal shock. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 44(10), 1925–1934 (2022).

Kumari, P. G. W. et al. An experimental study on tensile characteristics of granite rocks exposed to different high-temperature treatments. Geomech. Geophys. Geo. 5(1), 47–64 (2019).

Xia, C. C. et al. Preliminary study on mechanical property of basalt subjected to cyclic uniaxial stress and cyclic temperature. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 37(06), 1016–1024 (2015).

Zhu, Z. N. et al. Experimental study of physico-mechanical properties of heat-treated granite by water cooling. Rock. Soil. Mech. 39(S2), 169–176 (2018).

Jia, P. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties of water-cooled high temperature rock under cyclic loading. Trans. Beijing Inst. Technol. 43(02), 126–134 (2023).

Yuan, Y. et al. Study on crack dynamic evolution and damage-fracture mechanism of rock with pre-existing cracks based on acoustic emission location. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 201, 1–13 (2021).

Song, Y. J., Cheng, K. Y. & Meng, F. D. Research on acoustic emission characteristics of fractured rock damage under freeze-thaw action. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 40(02), 408–419 (2023).

Wang, Y. & Chen, W. H. Study on thermal stress field of triangle fracture of granite in high temperature environment. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 40(S2), 3074–3083 (2021).

Li, M., Liu, X. S. & Pan, Y. H. Mechanical properties of fractured sandstone after cyclic thermal shock. Rock. Soil. Mech. 44(05), 1260–1270 (2023).

Yuan, C. et al. Experimental investigation on the influence on mechanical properties and acoustic emission characteristics of granite after heating and water-cooling cycles. Geomech. Geophys. Geo. 9(1), 1–18 (2023).

Gong, C. et al. Evolution law and dominant frequency characteristics of acoustic emission sources during red sandstone failure process. JCCS 47(06), 2326–2339 (2022).

Nicksiar, M. & Martin, C. D. Evaluation of methods for determining crack initiation in compression tests on low-porosity rocks. Mec Roches. 45, 607–617 (2012).

Xiao, Y. M., Qiao, Y. F. & Li, H. R. Strain rate effect and acoustic emission characteristics of carbonaceous slates in uniaxial compression. TJU 50(09), 1276–1285 (2022).

LI, X. W., Yao, Z. S. & Huang, X. W. Investigation of deformation and failure characteristics and energy evolution of sandstone under cyclic loading and unloading. Rock. Soil. Mech. 42(06), 1693–1704 (2021).

Ning, J. G. et al. Estimation of Crack initiation and propagation thresholds of confined brittle coal specimens based on energy dissipation theory. Mec Roches 51(1), 119–134 (2018).

Liu, X. H. et al. Study on determination of uniaxial characteristic stress of coal rock under quasi-static strain rate. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 39(10), 2038–2046 (2020).

Liu, X. X. et al. Energy evolution and failure characteristics of single fissure carbonaceous shale under drying-wetting cycles. Rock. Soil. Mech. 43(07), 1761–1771 (2022).

Peng, J. et al. Experimental study of effect of water pressure on progressive failure process of rocks under compression. Rock. Mech. 34(04), 941–946 (2013).

Liu, L., Wang, S. J. & Yang, W. C. Strain rate effects on characteristic stresses and acoustic emission properties of granite under quasi-static compression. Front. Earth. Sc-Switz. 10, 1–21 (2022).

Li, C. B. et al. Experimental and theoretical study on the shale crack initiation stress and crack damage stress. JCCS 42(04), 969–976 (2017).

Liu, X. L. et al. Acoustic emission b-values of limestone under uniaxial compression and Brazilian splitting loads. Rock. Mech. 40(S1), 267–274 (2019).

Su, X. B. et al. Relationship between spatial variability of rock strain and b value under splitting condition. JCCS 45(S1), 239–246 (2020).

Dong, L. J. & Zhang, L. Y. Error analysis of b-value of acoustic emission for rock fracture. JYRSRI 37(08), 75–81 (2020).

Cai, M., Kaiser, K. P. & ., Tasaka, Y. Generalized crack initiation and crack damage stress thresholds of brittle rock masses near underground excavations. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. 41(5) (2004).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Study on crack dynamic evolution and damage-fracture mechanism of rock with pre-existing cracks based on acoustic emission location. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 201, 1–13 (2021).

Zhao, Y. Q. et al. Investigation on the influence of pore-fracture structure characteristics of coal rock on its damage evolution law. Coal Sci. Technol. 1–12 (2024).

Yang, D. J., Hu, J. H. & Zeng, P. P. Uniaxial acoustic emission from granite after triaxial cyclic predamage and chaotic fractal analysis. J. Nonferrous Met. 33(02), 619–629 (2023).

Wang, W. et al. Experiment of Fractal characteristics of Acoustic Emission of Sandstone under Triaxial Cyclic Loading and Unloading. Adv. Eng. Sci. 54(02), 90–100 (2022).

Wang, S. et al. Inside a highly concentrated full-tailed sand slurry containing APAM structural evolution characteristics. J. Nonferrous Met. 32(11), 3553–3566 (2022).

Xu, X. L. et al. Experimental study of the effect of loading rates on mechanical properties of granite at real-time high temperature. J. Nonferrous Met. 36(08), 2184–2192 (2015).

Xu, X. L. et al. Expermental research on m echanical characteristics of granite under temperature loads. JUST 28(04), 651–656 (2008).

Junique, T. et al. The use of infrared thermography on the measurement of microstructural changes of reservoir rocks induced by temperature. Appl. Sci-Basel. 11(2), 559 (2021).

Junique, T. et al. Microstructural evolution of granitic stones exposed to different thermal regimes analysed by infrared thermography. Eng. Geol. 106057, 286 (2021).

Shuailong, L. et al. Study on the damage mechanism and evolution model of preloaded sandstone subjected to freezing–thawing action based on the NMR technology. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 63(1), 1–23 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. Zheng Investigation of the mechanical behavior and continuum damage model of sandstone after freezing–thawing cycle action under different immersion conditions. B. Eeg. Geol. Environ. 81(12), 505 (2021).

Xie, Q. T. et al. A study of crack propagation measurement on sandstone with a single inclined flaw under uniaxial compression. Rock. Soil. Mech. 32(10), 2917–2921 (2011).

Bao, X. K. W. L. Y. et al. Damage evolution and fractal characteristics of granite under the influence of temperature and loading. Appl. Sci-Basel 14(13), 5500–5500 (2024).

Shuailong, L. et al. Investigation of the mechanical behavior of rock-like material with two flaws subjected to biaxial compression. Sci. Rep 14(1), 1–18 (2024).

Shuailong, L. et al. Investigation of the shear mechanical behavior of sandstone with unloading normal stress after freezing–thawing cycles. Machines. 9(12), 339 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors of the article sincerely appreciate and thank all the people who made it possible to implement this project.

Funding

This research is supported by the Basic Scientific Research Business Fee Project of Universities Directly under the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Grant No.2024XKJX009); Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia of China (Grant No.2024LHMS05044) and Central Support for Local Universities Reform and Development Project - Discipline Construction - Civil Engineering Quality Improvement and Cultivation Discipline Construction Project (Grant No. 0404052401).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xiankai Bao and Lingyu Wang designed the study and supervised the project. Guangqin Gui, Baolong Tian and Jianlong Qiao collected data. Shunjia Huang and Lizhi Wang performed the statistical analysis. Xiankai Bao and Lingyu Wang wrote the initial paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The Funding section in the original version of this Article was incomplete, where a grant fund was omitted. Full information regarding the corrections made can be found in the correction for this Article.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, X., Wang, L., Cui, G. et al. Mechanical properties and damage characterization of cracked granite after cyclic temperature action. Sci Rep 14, 29067 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80224-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80224-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effect of Thermal Treatment on the Fracture Toughness of Organic Soil

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2025)