Abstract

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is one of the most prevalent obesity-related diseases in women of reproductive age. Linkage between diet and PCOS are still controversial. Dietary obesity prevention score (DOS) is one of the new indicators of diet evaluation which have been previously linked to obesity. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to investigate the relationship between DOS and PCOS. In this case–control study, 100 newly diagnosed women with PCOS and 100 age–matched women without PCOS were assayed from clinics affiliated to Kashan university of medical sciences, Kashan, Iran. A validated semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire was used to evaluate food intakes. DOS was calculated based on previous published guideline. Anthropometric measurements were carefully measured by a trained nutritionist. A 10-houres fasting plasma blood sample was collected for all participants. Fasting blood sugar (FBS), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (CHOL), High density lipoprotein (HDL), Low density lipoprotein (LDL) and C - reactive protein (CRP) were measured based on laboratory methods. The mean age and BMI of study participants was 23.6 year and 24.9 kg/m2 respectively. After adjustment for potential confounders, adherence to DOS score was inversely associated with CRP levels. People in the top tertile of DOS had lower CRP level compared to people in the bottom tertile (3.71 compared to 4.48 mg/dl) (P = 0.04). In addition, participant in the top tertile of DOS had marginally significant higher level of FBS compared to participants in the bottom tertile (92.3 vs. 88.9 mg/dl, P = 0.051). After adjustment for all confounding factors people in the highest tertile of DOS had a 46% non-significant lower odds for PCOS compared to people in the lowest tertile (95% CI: 0.23–1.25; P-trend = 0.15). In the present study, an inverse significant association was seen between adherence to DOS and inflammation. However, no significant relationship was observed between DOS and odds of having PCOS. Further longitudinal studies are suggested to investigate the association between DOS and PCOS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrine gland dysfunction in women of reproductive age1. The main complaints of patients are ovarian disorders and infertility2. However due to the imbalance in hormone secretion and increased insulin secretion, these patients are prone to metabolic diseases, especially diabetes3. According Rotterdam criteria, the prevalence of PCOS among women was 17.8% globally in 2010 and 19.5% in Iran in 20151,2.

Some genetic and environmental risk factors have been linked to PCOS; especially obesity and overweight4. Previous documents has shown that a 5–10% reduction in weight can have promising results in improving the complications of PCOS5. Diet is one of the most modifiable risk factor which could affect the incidence and progression of PCOS6,7,8. The relationship between diet and PCOS has been investigated in previous studies and reached to inconsistent results9,10,11. Dietary Obesity prevention Score (DOS) is a new dietary assessment indicator which is suggested to predict obesity in population12. The consumption of vegetables, fruits, legumes, yogurt, nuts, fish, and the ratio of vegetable protein to animal protein are positively scored in DOS. While the consumption of red meat, processed meats, saturated animal fat, refined grains, ultra-processed foods, sugary beverages, beer and spirits are negatively scored. These foods in calculating DOS were carefully selected from foods which previously had strong evidence to be associated with weight changes12. It has been shown that higher adherence to DOS could be associated with 37% lower risk for obesity during 104,887 person-years12. No study has been previously investigated the association between DOS and PCOS. However, some previous studies have evaluated the relationship between some components of DOS and PCOS and reached to inconsistent results13. For example, higher dietary n-3 PUFA intake was associated with a lower prevalence of PCOS14 and reduced WC and BMI among PCOS patients15,16. In addition, the results of another study showed that consumption of legumes, fish/seafood and consumption of nuts could reduce the severity of PCOS symptoms17. In addition, in some studies, no statistically significant relationship was seen between in the consumption of fruits, vegetables, and sweetened beverages and PCOS18.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has been previously investigated the association between DOS and PCOS. In addition to this, most of previous studies on the association between diet and PCOS, have been conducted in Western countries9,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 and limited data are available in Middle Eastern countries, including Iran17,26,27,28,29,30. Whit an emphasis that diet modification is one of the most effective and least expensive approaches to prevent and management of PCOS, it is necessary to find new useful dietary recommendation to control the disease31,32. In addition, as obesity and overweight have impressive effects on PCOS33, we amid to investigate the relationship between dietary obesity prevention score and PCOS in a well-controlled case-control study.

Methods and analysis

Participants

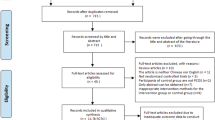

This case-control study was conducted from October 2022 to October 2023 to investigate the association between DOS and PCOS. The participants were selected from the women referring to medical clinics affiliated to Kashan University of Medical Sciences, Kashan, Iran. People were selected using convenient sampling method. One-hundred newly-diagnosed PCOS patients were included in this study. Inclusion criteria in the case group were: (1) being at age 16 to 35 years, (2) diagnosis of PCOS within the last month by a gynecologist using ultrasound method and according to Rotterdam criteria, (3) absence of any other gynecological diseases and other underlying diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, hypothyroidism, hyperprolactinemia, Cushing’s syndrome, eating disorders and congenital adrenal hyperplasia, (4) not taking drugs related to underlying and gynecological diseases, including hormonal drugs, contraceptive pills, glucocorticoids, etc., (5) not following a specific diet in the last three months, (6) not smoking and (7) not breastfeeding or pregnancy. In addition, 100 age-matched healthy women who referred to other departments of the same centers were selected as the control group. Inclusion criteria for control group were the same for the case group, except for not having PCOS based on the gynecologist diagnosis. Exclusion criteria in our study were failure to cooperate with the researcher until the end of the study and under-reporting (less than 800 kcal/d) or over-reporting (more than 4500 kcal/d) daily energy intake. All of participants completed and signed the informed consent form.

To determine the sample size for this study, we applied the formula for comparing two means. Since no previous study exactly matched the scope of our research, we relied on the most relevant published study available. Specifically, we referred to the study by Hosseini et al. which closely aligned with our primary objectives27. To calculate the sample size, we considered type I error rate (α) = 5% and type II error rate (β) = 10% (yielding a statistical power of 90%). Based on these parameters, the minimum sample size required was 88 participants per group. Allowing for a 15% attrition rate, we adjusted the final sample size to 100 participants per group. All methods were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. All experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (IR.KAUMS.MEDNT.REC. 1401,107(. Informed consent was obtained from all subject.

Diet assessment

Dietary information of study participants were collected by a 117 items semi-quantitative food frequency questioners (FFQ)34. This valid and reliable FFQ contains a list of usual food with normal and standard portion sizes which consume by Iranian. Subjects were asked to report the amount and the frequency of consumption of each food items listed in the questionnaire on a monthly, weekly or daily basis (grouping the answers with 9 options that range from never or less than once a month to 6 times or more per day). After fulfilling the FFQ by trained dietitian, the reported food item frequency was converted to gram per day using the USDA Table (35). We used Nutritionist IV software, which was modified for Iranian foods.

Calculation of DOS

The Dietary Obesity Prevention Score is a valid scoring algorithm based on food groups which have been previously linked to weight change12. It contains 14 food groups. As Iranian are Muslim and the consumption of alcoholic drink are forbidden, the consumption of beer was excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the score was calculated based on 13 food groups. First, the consumption of all food groups was categorized into tertiles. Then, food groups which had an inverse relationship with obesity (including 7 groups of vegetables, fruits, legumes, yogurt, nuts, fish and vegetable-to-animal protein ratio) was given a positive score from 1 to 3 and groups that had a positive relationship with obesity (including 6 groups of red meat, processed meats, saturated animal fat, refined grains, processed foods and sugary beverages) was given a negative score from 3 to 1. The final score of DOS was obtained from consuming the total score of these 13 food groups. A higher DOS score is associated with better prevention for obesity.

Biochemical assessments

Fasting blood samples of the all study participants were gathered after 10–12 h of fasting in the early morning by vein puncture. Blood samples were centrifuged after 30–45 min following standard procedures. Fasting blood sugar was determined by enzymatic colorimetric and glucose oxidase method. Then, the colorimetric detection of cholesterol and triglyceride was done using cholesterol oxidase and glycerol phosphate respectively. High density lipoprotein (HDL) was measured after apo-lipoprotein beta precipitation with phosphotungstic acid. Low density lipoprotein (LDL) was calculated using Pars Azmoun commercial kit. The amount of C - reactive protein (CRP) was measured by turbidometry or turbidity method and with APPTEC kit.

Assessment of other variables

Demographic and medical information was collected using a general questionnaire and through face-to-face interviews. In this questionnaire, information related to demographic status (age, education, occupation, marital status, family size, number of children and income) and medical history (family history of diseases, age of onset of menstruation, amenorrhea, hair loss, acne, menstrual cycle irregularity, medication use and supplement use) were evaluated. Weight was measured without shoes and with light clothes, using Seca digital scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. The scale was calibrated every morning or during the day, using standard weights of 1 kg and 2 kg to avoid errors. Height was measured using a wall-mounted height meter in a standing position, without shoes, while the heel of the person’s foot is completely attached to the wall and her gaze is facing the front. Waist circumference (WC) was measured using a non-elastic tape measure at the distance between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest. Measurements were recorded with an accuracy of 0.1 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. In addition, people were asked to rest for at least 30 min and then blood pressure was measured at right arm in the sitting position, using a digital sphygmomanometer (GLAMOR), twice with an interval of at least 6 h and the average was considered as the individual’s blood pressure. Moreover, the shortened form of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ-SF) was used to evaluate physical activity of study participants. This questionnaire assesses the time and frequency of low, moderate and intense activities of more than 10 min during a week. The last question is also about the duration and frequency of sitting in the last week. In this questionnaire, intense or moderate physical activity refers to activities that allow a person to work hard enough to raise their heart rate and sweat. The physical activity-metabolic equivalent (MET) for low, moderate and intense activities is 3.3, 4.0 and 8.0, respectively. Then the activity score of each person was calculated by multiplying the MET level of activity * minutes * number of times per day. Finally, to calculate the qualitative scale, the subjects’ physical activity was divided into 3 groups: low (< 600), moderate (600 to1500) and intense (> 1500). The validity and reliability of this questionnaire has already been confirmed in previous study36.

Statistical analyses

Normality of data was checked using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. To remove the effect of energy on the DOS score, energy-adjusted amount of DOS was calculated using residual method37. Then, to check the more accurate relationship between DOS and PCOS, it categorized into tertiles using SPSS. To compare quantitative variables between cases and controls and across tertiles of DOS independent t test and ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) test was used, respectively. Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables between cases and controls and among tertiles of DOS. ANCOVA (Analysis of covariance) test was applied when adjustment for confounders was needed. Binary logistic regression model was used for multivariate analysis of the associations between DOS and the odds of having PCOS. Three model of adjustment was designed to seek the association: In model 1, adjustment was made for age and daily energy intake. Further adjustment was made for education, income, (based on previous studies38,39,40), occupation, marital status, physical activity level (PAL), in model 2. Finally, in full-adjusted model (model 3) further adjustment was done for BMI. All analysis was done using SPSS (version 19.0). P < 0.05 was considered as significance level.

Results

The mean age and BMI of study participants 23.6 year and 24.9 kg/m2 respectively. General characteristics of study participants are provided in Table 1. The mean of weight and BMI in PCOS people were significantly higher than control group (67.5 vs. 63.3 kg and 25.8 vs. 24.0 kg/m2, respectively) (p < 0.05). PCOS cases also had greater WC (82.4 vs. 79.4 cm) compared to control groups. This difference was marginally significance (P = 0.051(. People with PCOS were more likely to be married, to be employed and had higher medication use compared to control group (p < 0.05). They also were less likely to be graduated and had lower income compared to control group (p < 0.05). In addition, women with PCOS had less supplement consumption compared to healthy women. This difference was marginally significant (P = 0.05). No other significant difference was seen between cases and controls in term of age of onset of menstruation, family size, number of children and PAL (P > 0.05).

People in the top tertile of DOS had significantly higher age of onset of menstruation compared to people in the bottom tertile (13.1 compared to 12.6 y) (p < 0.05). They also were more likely to be married compared to people in the bottom tertile of DOS (p < 0.05). However, no other significant association was seen in terms of other variables including weight, BMI, WC, family size, number of children, amount of income, education level, employment rate, taking other drugs and supplement, PAL and tertiles of DOS (P > 0.05).

Table 2 provides the comparison of mean and standard error of dietary intakes among tertiles of DOS. Participants in the highest tertile of the DOS had significantly higher daily energy and carbohydrate intake compared to people in the lowest tertile (2619 vs. 2123 kcal/d and 337 vs. 295 gr/d, respectively; P < 0.05). They also had significantly higher intake of iron, zinc, magnesium, vitamin E, vitamin C, vitamin B9, vitamin B1, and vitamin B6 as well as fruit, vegetable, Legumes Vegetable to animal protein ratio compared to people in the lowest tertile of DOS (P < 0.05). In addition, people with the highest DOS score had lower intake of saturated fatty acid and vitamin A as well as refined grains, ultra-processed food and sugary beverages compared to people with the lower DOS score (P < 0.05). However, there were no other statistically significant differences between the consumption of protein, fat, cholesterol, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), calcium, selenium, vitamin D, vitamin B12, yogurt, nuts, fish, red meat, processed meat and animal fat and DOS score (P > 0.05).

Comparison of mean and standard error of biochemical indicators among tertiles of DOS are shown in Table 3. People in the highest tertile of DOS had lower level of CRP (3.71 vs. 4.48 mg/dl) compared to people in the lowest tertile. (P = 0.04). In addition, participant in the top tertile of DOS had higher level of FBS compared to participants in the bottom tertile (92.3 vs. 88.9 mg/dl). This finding was marginally significant (P = 0.051). No other significant association was seen between DOS and other biochemical indictors including HDL, LDL, TG, Total Col, SBP, DBP (p > 0.05).

Table 4 provides the results of the regression logistic analysis on the association between DOS and odds of PCOS. In the crude model people in the third tertile of DOS had 13% non-significant decreased odds for PCOS compared to people in the first tertile (95% CI: 0.43–1.78; P-trend = 0.71). In the first model of adjustment, after adjustment for age and daily energy intake, participants in the top tertile of DOS had 20% non-significant increased odds for PCOS compared to people in the bottom tertile (95% CI: 0.60–2.39; P-trend = 0.47). In the second model, further adjustments were also for education, income, occupation, marital status, medication use, PAL, people in the highest tertile of DOS had 49% non-significant decreased odds for PCOS compared to people in the first tertile (95% CI: 0.22–1.20; P-trend = 0.12). Finally, in the full-adjusted mode (model 3) further adjustment was done for BMI. In this model of analysis, who were in the third tertile of DOS had 46% non-significant decreased odds for PCOS compared to people in the first tertile (95% CI: 0.43–1.78; P-trend = 0.71).

Discussion

In the present study, an inverse significant association was seen between adherence to DOS score and CRP. However, no significant association was seen between DOS and odds of PCOS. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to investigate the relationship between DOS and PCOS.

PCOS could be associated with serious chronic complications such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and mental illnesses41,42. In our study no significant association was observed between DOS and PCOS. Very limited data are available on the linkage between DOS and chronic diseases12,43. As no study was done in the association between DOS and PCOS, we assayed studies which investigated the association between food groups in DOS score and PCOS. In consistent with our result, no significant difference was seen between mean daily intake of cereals, legumes, vegetables, fruits and nuts among young women with or without PCOS in a case–control study44. In addition consumption of fruits, vegetables, and sweetened beverages were not significantly related to PCOS in another cross-sectional study45. Moreover, no significant relationship was observed between Alternative Healthy Eating Index, Relative Mediterranean Diet Score, Alternative Mediterranean Diet Score and Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and PCOS46. However, in contrast with our result, Ling Lu et al. concluded that dietary intake of n-3 PUFA, mainly eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), could negatively correlated with PCOS-related parameters, such as BMI, fasting insulin, total testosterone, and high-sensitivity CRP14. Also, in another study, dietary intake of legumes, fish/seafood, and nuts was inversely associated with the severity of PCOS symptoms22. It must be kept in mind that the cases who were included in Ling Lu et al. study were not newly-diagnosed PCOS patients, which could affect their diet due to the diagnosis of disease. In addition diagnosis of PCOS in our study was based on the gynecologist diagnosis (compared to Ling Lu study which was based on the medical record in the past). This study also has the larger sample size (almost 3-folds) compared to our study14. In addition, different dietary assessment method was applied in Luigi Barrea et al. study (the seven days food diary records)22.

Studies have shown that consuming unhealthy foods can slow down the body’s metabolism and reduce the number of calories consumed and challenge maintaining a healthy weight. Junk foods indirectly affect androgen levels through insulin resistance (IR). Elevated insulin levels decrease sex hormone-binding globulin a regulatory protein that suppresses the activity of androgens in women, and when cytokines cause IR, hyperandrogenism occurs and its symptoms appear18. In addition, IR, which is a common and serious complication of PCOS, leads to metabolic syndrome and related diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Meanwhile, high consumption of many unhealthy foods such as fast food, soft drinks, sweets and processed foods is common among women with PCOS47. For example, one study found that a well-managed diet combined with a healthy lifestyle could improve IR, cardiovascular health, and metabolism48. The age of the participants in this study was younger than us (15–21 y).

Based on our results, DOS score was inversely associated with CRP in our participants. In consistent with our results, CRP levels were higher in PCOS women who consumed less legumes, fish and nuts than in the control group23. Also fruit and vegetable consumption was significantly inversely related to CRP in another study49. However, some other studies failed to reach any significant association between diet and inflammation. For instant, dietary refined grain was not associated with CRP levels in 1015 participants50. Another study found no effect of nut-enriched diet on serum CRP levels in patients with stable coronary artery disease51. It should be noted that theas stuuise was conducted on differend patitiona (Atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease, redpectively) which could represent different mechanisim pathwasy.

There are some possible mechanisms. Fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia can reduce the availability of nitric oxide and increase the production of free radicals. It also activates inflammation by modulating the function of protein kinase C and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB)52. In addition, refined starch and sugar cause a rapid increase in blood glucose and insulin levels and subsequently a decrease in blood sugar, which leads to hypoglycemia and hunger. Decreased fat oxidation by consuming high glycemic index foods is an important stimulus for inflammation through this mechanism. For this reason, high-fiber foods that help reduce the glycemic response in the diet can be beneficial in reducing inflammation41.

This study had several strengths. First, this study was the first to investigate the association between DOS and PCOS. Second, PCOS patients in our study were newly-diagnosed patients who their disease was confirmed by an expert gynecologist and valid tools. Selecting these newly diagnosed patients can reduce the effect of possible dietary changes due to the disease diagnosis. Third, we used validated and reliable questionnaire to collect our data. Forth, we tried our best to consider a wide range of confounding variables to seek a clear association between diet and disease. Fifth, we also collect data on blood metabolic and inflammatory indicators to better clarify how diet could be related to disease. However, some limitations must be considered. Due to the case-control design of the present study, the causality association between DOS and PCOS could not be interpreted. In addition, although we do adjustment for a wide range of confounding variables, the residual effect of uncontrolled intervening variables should be considered. However, we did not include a wide range of chronic disease which could affect our results. In addition, we selected age-matched controls to reduce this bias. Despite the use of a valid FFQ to assess dietary intakes, misclassification and recall bias must be considered. FFQ is the most common used dietary questionnaire in nutritional surveys. In our study FFQs were completed through a face-to-face interview by a trained nutritionist to reduce its biases.

In conclusion, diet could be considered as an important factor in controlling PCOS. Since the consumption of inflammation-induced foods including red meat, processed meats, and saturated fats are restricted in DOS score, it is expected that following a high DOS diet can help reduce inflammation. As inflammation is a risk factor for many chronic diseases, including PCOS, its reducing could be benefit in potion with PSOC. As DOS score is emphasizing on eating healthy dietary source of fibers and other obesity prevention factors, it is recommended to investigate its relationship with PCOS in further larger cohort studies.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the rules and regulations of the Research Center for Biochemistry and Nutrition in Metabolic Diseases at the Kashan University of Medical Science, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

March, W. A. et al. The prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome in a community sample assessed under contrasting diagnostic criteria. Hum. Reprod. 25(2), 544–551 (2010).

Jalilian, A. et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovary syndrome and its associated complications in Iranian women: A meta-analysis. Iran. J. Reprod. Med. 13(10), 591 (2015).

Hussein, A. A., Baban, R. S., Hussein, A. G. Ghrelin and insulin resistance in a sample of Iraqi women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Iraqi J. Med. Sci. 12(1) (2014).

Choudhary, K. et al. An updated overview of polycystic ovary syndrome. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 7(3), 1–13 (2019).

Jiskoot, G. et al. A three-component cognitive behavioural lifestyle program for preconceptional weight-loss in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Reprod. Health. 14(1), 1–12 (2017).

Lim, S. S., Hutchison, S. K., Van Ryswyk, E., Norman, R. J., Teede, H. J., Moran, L. J. Lifestyle changes in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Cochrane Datab. Syst. Rev. 2019(3) (2019).

Ma, Y., Zheng, L., Wang, Y., Gao, Y. & Xu, Y. Arachidonic acid in follicular fluid of PCOS induces oxidative stress in a human ovarian granulosa tumor cell line (KGN) and upregulates GDF15 expression as a response. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 865748 (2022).

Khondker, L., Nabila, N. Comparison of lifestyle in women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and healthy women.

Nybacka, Å., Hellström, P. M. & Hirschberg, A. L. Increased fibre and reduced trans fatty acid intake are primary predictors of metabolic improvement in overweight polycystic ovary syndrome—Substudy of randomized trial between diet, exercise and diet plus exercise for weight control. Clin. Endocrinol. 87(6), 680–688 (2017).

Shishehgar, F. et al. Comparison of dietary intake between polycystic ovary syndrome women and controls. Glob. J. Health Sci. 8(9), 302 (2016).

Moran, L., Brown, W., McNaughton, S., Joham, A. & Teede, H. Weight management practices associated with PCOS and their relationships with diet and physical activity. Hum. Reprod. 32(3), 669–678 (2017).

Gómez-Donoso, C. et al. A food-based score and incidence of overweight/obesity: The dietary obesity-prevention score (DOS). Clin. Nutr. 38(6), 2607–2615 (2019).

Rajaeieh, G., Marasi, M., Shahshahan, Z., Hassanbeigi, F. & Safavi, S. M. The relationship between intake of dairy products and polycystic ovary syndrome in women who referred to Isfahan University of Medical Science Clinics in 2013. Int. J. Prevent. Med. 5(6), 687 (2014).

Lu, L. et al. Dietary and serum n-3 PUFA and polycystic ovary syndrome: a matched case–control study. Br. J. Nutr. 128(1), 114–123 (2022).

Oner, G. & Muderris, I. Efficacy of omega-3 in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 33(3), 289–291 (2013).

Khani, B., Mardanian, F. & Fesharaki, S. J. Omega-3 supplementation effects on polycystic ovary syndrome symptoms and metabolic syndrome. J. Res. Med. Sci. 22(1), 64 (2017).

Shahdadian, F. et al. Association between major dietary patterns and polycystic ovary syndrome: Evidence from a case-control study. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 44(1), 52–58 (2019).

Zhu, J.-l, Chen, Z., Feng, W.-J., Long, S.-l & Mo, Z.-C. Sex hormone-binding globulin and polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Chim. Acta 499, 142–148 (2019).

Marsh, K. A., Steinbeck, K. S., Atkinson, F. S., Petocz, P. & Brand-Miller, J. C. Effect of a low glycemic index compared with a conventional healthy diet on polycystic ovary syndrome. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 92(1), 83–92 (2010).

Shang, Y., Zhou, H., Hu, M. & Feng, H. Effect of diet on insulin resistance in polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105(10), 3346–3360 (2020).

Boyd, M. & Ziegler, J. Polycystic ovary syndrome, fertility, diet, and lifestyle modifications: A review of the current evidence. Top. Clin. Nutr. 34(1), 14–30 (2019).

Barrea, L. et al. Adherence to the mediterranean diet, dietary patterns and body composition in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Nutrients 11(10), 2278 (2019).

Larsson, I. et al. Dietary intake, resting energy expenditure, and eating behavior in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome. Clin. Nutr. 35(1), 213–218 (2016).

Nybacka, Å. et al. Randomized comparison of the influence of dietary management and/or physical exercise on ovarian function and metabolic parameters in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil. Steril. 96(6), 1508–1513 (2011).

Nybacka, Å., Carlström, K., Fabri, F., Hellström, P. M. & Hirschberg, A. L. Serum antimüllerian hormone in response to dietary management and/or physical exercise in overweight/obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 100(4), 1096–1102 (2013).

Panjeshahin, A., Salehi-Abargouei, A., Anari, A. G., Mohammadi, M. & Hosseinzadeh, M. Association between empirically derived dietary patterns and polycystic ovary syndrome: A case-control study. Nutrition 79, 110987 (2020).

Hosseini, M. S., Dizavi, A., Rostami, H., Parastouei, K. & Esfandiari, S. Healthy eating index in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A case-control study. Int. J. Reprod. BioMed. 15(9), 575 (2017).

Sharkesh, E. Z., Keshavarz, S. A., Nazari, L. & Abbasi, B. Empirical Dietary Inflammatory Pattern is positively associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: A case control study. Nutr. Res. 122, 123–129 (2024).

Kazemi, M. et al. Comparison of dietary and physical activity behaviors in women with and without polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 39 471 women. Hum. Reprod. Update 28(6), 910–955 (2022).

Mehrabani, H. H. et al. Beneficial effects of a high-protein, low-glycemic-load hypocaloric diet in overweight and obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized controlled intervention study. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 31(2), 117–125 (2012).

Moran, L. J., Noakes, M., Clifton, P. M., Tomlinson, L. & Norman, R. J. Dietary composition in restoring reproductive and metabolic physiology in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88(2), 812–819 (2003).

Stańczak, N. A., Grywalska, E. & Dudzińska, E. The latest reports and treatment methods on polycystic ovary syndrome. Ann. Med. 56(1), 2357737 (2024).

Itriyeva, K. The effects of obesity on the menstrual cycle. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 52(8), 101241 (2022).

Malekshah, A. et al. Validity and reliability of a new food frequency questionnaire compared to 24 h recalls and biochemical measurements: Pilot phase of Golestan cohort study of esophageal cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 60(8), 971–977 (2006).

Montville, J. B. et al. USDA food and nutrient database for dietary studies (FNDDS), 5.0. Procedia Food Sci. 2, 99–112 (2013).

Moghaddam, M. B. et al. The Iranian version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) in Iran: Content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and stability. World Appl. Sci. J. 18(8), 1073–1080 (2012).

Willett, W. & Stampfer, M. J. Total energy intake: Implications for epidemiologic analyses. Am. J. Epidemiol. 124(1), 17–27 (1986).

Goh, J. E. et al. Assessment of prevalence, knowledge of polycystic ovary syndrome and health-related practices among women in klang valley: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Endocrinol. 13, 985588 (2022).

Damone, A. L. et al. Depression, anxiety and perceived stress in women with and without PCOS: A community-based study. Psychol. Med. 49(9), 1510–1520 (2019).

Rubin, K. H., Andersen, M. S., Abrahamsen, B. & Glintborg, D. Socioeconomic status in Danish women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A register-based cohort study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 98(4), 440–450 (2019).

Glintborg, D., Hass Rubin, K., Nybo, M., Abrahamsen, B. & Andersen, M. Morbidity and medicine prescriptions in a nationwide Danish population of patients diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 172(5), 627–638 (2015).

Glintborg, D. & Andersen, M. MANAGEMENT OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Morbidity in polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 176(2), R53–R65 (2017).

Gómez-Donoso, C. Diet-related approaches for primary prevention of obesity and premature mortality (2021).

Rani, R., Sangwan, V., Rani, V. Assessment of nutritional status of young women with and without PCOS in Fatehabad District, Haryana.

Wang, Z. et al. Dietary intake, eating behavior, physical activity, and quality of life in infertile women with PCOS and obesity compared with non-PCOS obese controls. Nutrients 13(10), 3526 (2021).

Cutillas-Tolín, A. et al. Are dietary indices associated with polycystic ovary syndrome and its phenotypes? A preliminary study. Nutrients 13(2), 313 (2021).

Hajivandi, L., Noroozi, M., Mostafavi, F. & Ekramzadeh, M. Food habits in overweight and obese adolescent girls with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): A qualitative study in Iran. BMC Pediatrics 20(1), 1–7 (2020).

Hmedeh, C., Ghazeeri, G. & Tewfik, I. Nutritional management in polycystic ovary syndrome: Challenges and opportunities. Int. J. Food Saf. Nutr. Public Health 6(2), 120–130 (2021).

Navarro, P. et al. Vegetable and fruit intakes are associated with hs-CRP levels in pre-pubertal girls. Nutrients 9(3), 224 (2017).

Masters, R. C., Liese, A. D., Haffner, S. M., Wagenknecht, L. E. & Hanley, A. J. Whole and refined grain intakes are related to inflammatory protein concentrations in human plasma. J. Nutr. 140(3), 587–594 (2010).

Ghanavati, M. et al. Effect of a nut-enriched low-calorie diet on body weight and selected markers of inflammation in overweight and obese stable coronary artery disease patients: A randomized controlled study. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 75(7), 1099–1108 (2021).

Beręsewicz, A. NADPH oxidases, nuclear factor kappa B, NF-E2-related factor2, and oxidative stress in diabetes 129–137 (Elsevier, 2020).

Acknowlegements

We are very thankful to Kashan University of Medical Science to financial support for this research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.M contributed in conception, design, search, statistical analyses, data interpretation and manuscript drafting. H.G contributed in design and data interpretation.M.S contributed in design data. A.A contributed in conception, design, statistical analyses and supervised the study.N.SH contributed in supervised the study. H.Z contributed in edit the study. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahabady, M., Zolfaghari, H., Samimi, M. et al. The association between dietary obesity-prevention score (DOS) and polycystic ovary syndrome: a case-control study. Sci Rep 14, 28618 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80238-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80238-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Analysis of obesity prevalence and trend prediction among professional women in a hospital from 2010 to 2024: a weight management perspective

BMC Public Health (2025)

-

A novel obesity-prevention dietary score is associated with favorable metabolic status and lower blood pressure in obesity

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2025)