Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is often detected at advanced stages among patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV), underscoring the urgency for more precise surveillance tests. Here, we compare the clinical performance of the novel - GAAD (gender [biological sex], age, alpha-fetoprotein [AFP], protein-induced by vitamin K absence-II [PIVKA-II]) and GALAD (gender [biological sex], age, AFP, Lens-culinaris AFP [AFP-L3]), PIVKA-II) algorithms to assess the utility of AFP-L3 for distinguishing HCC from benign chronic liver disease (CLD) in Chinese patients with predominantly chronic HBV infection. Eligible adults were enrolled, and biomarkers were measured using Elecsys (Cobas) or µTASWAKO assays. In total, 411 participants provided serum samples (HCC, n = 176 [early-stage, n = 110]; CLD, n = 136; specificity n = 101). HBV was the underlying disease etiology for most participants (HCC, 95%; benign CLD, 72%). For GAAD (Cobas), GALAD (Cobas), and GALAD (µTASWAKO), AUCs were 93.1% (95% CI: 90.0–96.2), 93.2% (90.0–96.3), and 92.7% (88.4–96.9) for early-stage, and 95.6% (93.6–97.6), 95.6% (93.6–97.7), and 95.8% (93.2–98.3) for all-stage HCC, versus CLD, respectively. Interestingly, both GAAD and GALAD algorithms demonstrated comparable diagnostic performance regardless of disease etiology (HBV vs. non-HBV), presence of cirrhosis, geographic region, and within pan-tumor specificity panels (p < 0.001), indicating AFP-L3 may have a negligible role in HCC surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver cancer remains a global health concern, with incidence projected to rise approximately 55% by 2040, in line with the growing population1. In particular, high incidence and mortality rates are observed in Asia, with approximately 73% of all new liver cancer cases and associated deaths reported in Asia alone;1 the majority of these (60%) are reported in China2. Similarly, Hong Kong has a high prevalence of liver cancer, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) the third most common cause of cancer-associated deaths3. Risk factors for HCC include alcohol-related cirrhosis and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH)4,5,6. However, viral hepatitis infection, primarily hepatitis B virus (HBV), represents a major risk factor for chronic liver disease (CLD) and subsequent development of HCC in around half of all HCC cases7,8.

Despite nationwide vaccination programs and therapeutic developments, China has a high intermediate prevalence of HBV (6.89%), accounting for one third of all HBV infections and deaths globally9,10. Notably, there is a high prevalence of HBV in women of child-bearing age in China, resulting in high levels of perinatal transmission10. As a result, ~ 60% of HCC cases reported in China have HBV-related etiology, which confers a more malignant phenotype of HCC, characterized by rapid progression7. HBV contributes to the development of HCC through multiple mechanisms, including chronic inflammation and chromosomal instability through integration of HBV DNA (e.g., insertional mutagenesis in proto-oncogenes and tumor suppressors, and expression of mutant HBV proteins)11,12. These epigenetic changes are induced by the HBV-encoded oncogene X protein (HBx), which contributes to carcinogenesis by modifying the transcription of DNA methyltransferase and inducing cellular oxidative stress12,13,14.

Furthermore, the increasing incidence of obesity and obesity-related diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, in Asian populations has resulted in an increased prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), which is associated with an increased risk of HCC4. In addition, MASH, defined by lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning, was identified in 63% of patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in an Asian multi-center cohort and was associated with an increased risk of fibrosis progression4. As the coexistence of both chronic HBV infection and MAFLD is becoming increasingly common in the Chinese population, the occurrence of HCC in these patients is of significant concern17.

The high prevalence of HBV and the associated risk factors for HCC facilitated the implementation of surveillance programs for at-risk individuals, including those with viral hepatitis and/or cirrhosis, with the intention of detecting HCC in earlier stages. Timely diagnosis of HCC is essential to improve prognosis as curative therapies are more feasible for early-stage disease18), and it has been shown to account for the increased five-year survival rate observed for early- (> 70%) compared with advanced-stage HCC (< 20%)19,20,21.

In China, surveillance using ultrasound, with or without profiling of the biomarker, α-fetoprotein (AFP), is recommended every 6 months for high-risk individuals22,23,24. However, ultrasound, AFP and other serum biomarkers, such as protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II) (previously des-γ carboxyprothrombin [DCP]) and Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive fraction of AFP (AFP-L3), have demonstrated limited sensitivity for detection of HCC when used as standalone indicators22,23,24,25.

The development of diagnostic algorithms that combine patient demographic characteristics with the measurement of multiple serum biomarkers have further improved early detection of HCC26,27,28,29. One such algorithm, GALAD (gender [biological sex], age, α-fetoprotein [AFP], Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive fraction of AFP [AFP-L3], protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II [PIVKA-II]), combines gender (sex at birth) and age, with the measurement of three serum biomarkers (AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II), and has demonstrated superior clinical performance versus single biomarkers for the differentiation of HCC and CLD29,30,31. This is reflected in the current recommendations in China, where serum AFP combined with AFP-L3 and PIVKA-II are recommended to improve the detection of early-stage liver cancer32.

Notably, in populations with a high burden of viral hepatitis, such as Chinese and other Asian populations, the impact of antiviral therapies on serum biomarkers and their diagnostic value must be considered. For example, AFP has been shown to have high sensitivity for the detection of HCC, with optimal cut-off values lower in those receiving antiviral therapy for chronic viral hepatitis compared with those not receiving antiviral therapy33,34. Furthermore, AFP has also demonstrated improved clinical performance in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and preserved liver function as a result of antiviral therapy35, suggesting that AFP-L3 may no longer meaningfully contribute to the detection of HCC, either as a standalone biomarker or as part of the GALAD diagnostic algorithm. As such, the GAAD (gender [biological sex], age, α-fetoprotein [AFP], protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II [PIVKA-II]) algorithm was developed to assess the utility of AFP-L3 for distinguishing early-stage HCC from benign chronic liver disease36. Recently, the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China noted that the simplified GAAD diagnostic algorithm has a similar diagnostic performance to GALAD (highest level evidence, strong recommendation)37. However, there is currently no comparative study evaluating the efficacy of these diagnostic algorithms within a Chinese population. Therefore, in this study, we compared the clinical performance of GAAD and GALAD algorithms for the detection of HCC versus benign CLD in a Chinese subset population with patients with predominantly chronic hepatitis from an international, multicenter, case–control study.

Methods

Study population

This study was conducted within a case–control cohort of individuals aged ≥ 18 years, who were prospectively enrolled at two centers in the People’s Republic of China and Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China, as part of the STOP-HCC-MCE study38. To be eligible for inclusion for clinical performance analysis, participants had a first-time HCC diagnosis, confirmed by either radiology according to international guidelines (or a ≥ 1 cm lesion showing arterial-phase hyper enhancement in combination with washout appearance and/or capsule by quadruple-phase computed tomography scan or multiphase contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging22) or by positive pathology within 6 months of enrolment. Briefly, the BCLC staging system was used to categorize patients with HCC into one of the following disease stages: very early HCC (stage 0; single nodule ≤ 2 cm without vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread in a asymptomatic patient with preserved liver function); early HCC (stage A; single nodule or ≥ 3 nodules < 3 cm without macrovascular invasion or extrahepatic spread in an asymptomatic patient [performance status (PS) 0]); intermediate HCC (stage B; multifocal HCC with no vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread in an asymptomatic patient with preserved liver function [PS 0]); advanced HCC (stage C; patients with vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread presenting with PS ≥ 2 and preserved liver function); end-stage (stage D; major cancer-related symptoms [PS > 2] and/or impaired liver function without the option of liver transplant due to HCC burden or non–HCC–related factors).

Eligible CLD controls comprised of at-risk patients with either cirrhotic or non-cirrhotic CLD (resulting from HBC or HCV infection, alcoholic liver disease, or MASH) and confirmed absence of HCC by imaging within the previous 12 months. Exclusion criteria for both the HCC and CLD groups included any other form of cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), recurrent HCC, or previous or current treatment for HCC, glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, or treatment with anti-vitamin K coagulant therapy (e.g., warfarin, phenprocoumon, or acenocoumarol).

For the specificity panel, samples from patients with other malignancies (e.g., colorectal cancer) and other benign diseases (e.g., liver cysts, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis) were included. Patients with glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2, cholangiocarcinoma, and/or pancreatic cancer were excluded from this analysis due to low sample numbers.

All approvals were obtained from the relevant ethics committees and institutional review boards for all study sites involved in sample collection. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant local guidelines and regulations. Each participant provided informed consent before enrolment, and local rules regarding informed consent for the subsequent use of collected samples were followed.

Serum sample collection and assessment

Serum samples were collected ≥ 1 day before any planned procedures requiring general anesthesia and were stored at − 70 °C at the collection sites. Serum levels of PIVKA-II, AFP, and AFP-L3 were measured using Elecsys assays on the Cobas e 601 analyzer, or µTASWAKO assays on the Fujifilm Micro Total Analysis System WAKO analyzer. Predefined cut-off values used for the detection of HCC versus benign CLD were as follows: 20 ng/mL for AFP (Elecsys); 2.3 ng/mL for AFP-L3 (Elecsys); 28.4 ng/mL for PIVKA-II (Elecsys); 2.57 (range 0–10) for GAAD (Cobas); 2.47 (range 0–10) for GALAD (Cobas), and − 0.63 for GALAD (µTASWAKO). Additional cut-off values for GALAD (µTASWAKO) were also assessed, corresponding to GAAD (Cobas) specificity of 90%.

GAAD and GALAD (Cobas) algorithm development

The GAAD and GALAD (Cobas) algorithm development process has been previously described38. In summary, multivariate analyses were carried out to identify the best-performing panel of biomarkers for HCC detection using two methods, lasso regression (no fixed panel size) and exhaustive search with logistic regression (fixed panel size of two to four biomarkers). The full data set from the previous algorithm development study (STOP-HCC-ARP) was used to train logistic regression models for the two top-performing clinical algorithms (GAAD and GALAD), with diagnosis of HCC (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer [BCLC]-stage independent) as the predictor variable38. The cut-offs were calculated on the predictor variable from 90% specificity.

Statistical analysis

The clinical performance of the GAAD and GALAD algorithms, and that of the individual biomarkers alone, were compared using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and area under the curve (AUC) values. For sensitivity and specificity analyses, the derived 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated from the binomial distribution using the Clopper–Pearson method. P-values comparing non-inferiority of AUCs were calculated using the H0 hypothesis AUC (Test1) < AUC (Test 2)-0.01 with a studentized bootstrap approach using N = 1000 bootstrap replicates. For the specificity panel, p-values were calculated using binomial tests with Bonferroni correction for every marker using the cut-offs listed previously, and a specificity value ≥ 90%38; disease groups with fewer than 5 patient samples were excluded from analysis.

Results

Study population

In total, 312 Chinese participants enrolled in this case–control study provided confirmed diagnostic samples (HCC, n = 176; benign CLD, n = 136) for the clinical performance analysis, and an additional 101 participants were included in the specificity panel cohort (Fig. 1).

Study design for the Chinese cohort (Subset of STOP-HCC-MCE) (A) and baseline disease characteristics (B,C). *Reasons for exclusion were: missing required laboratory parameter data (n = 37); GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 19); other cancer diagnosis (n = 11); non-confirmed diagnosis (n = 8); incomplete/incorrect sample processing (n = 4); current/previous treatment with anti-vitamin K coagulant therapy (n = 3); written informed consent not obtained (n = 2); sponsor decision (n = 2) and recurrent HCC (n = 1). †Participants were excluded due to low number of samples (n < 5).

In the clinical performance cohort, the majority of patients were male (total HCC, 85.8%; benign CLD controls, 69.1%), and the mean age in the HCC group and the benign CLD group, respectively, was 55.4 years and 46.5 years (Table 1). HBV was the underlying disease etiology for the majority of participants (HCC, 94.9%; benign CLD, 72.1%) (Fig. 1b), and underlying cirrhosis was present in 73.3% and 33.8% of the HCC group and the benign CLD group, respectively. BCLC stage varied across the HCC group, with most participants classified as having early-stage HCC (BCLC 0–A, 62.5%) compared with late-stage HCC (BCLC B–D, 37.5%) (Fig. 1c). The proportion of participants receiving antiviral therapy was similar between groups (HCC, 63.1%; benign CLD, 61.0%) (Table 1). Baseline demographics and characteristics according to clinical study site are shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Method comparison and specificity panel analysis

Based on weighted Deming regression analyses, excellent analytical method agreement was observed between GALAD (µTASWAKO) and GAAD (Cobas) (Pearson’s r = 0.965; p < 0.001) and GALAD (Cobas) (Pearson’s r = 0.972; p < 0.001) algorithms in this Chinese cohort (Fig. 2a, b).

Method comparison and specificity panel—weighted Deming regression fit of agreement between GALAD (Cobas) and GALAD (µTASWAKO) (A) and GAAD (Cobas) and GALAD (µTASWAKO) (B). Specificity panel data across disease groups for GAAD (Cobas) (C), GALAD (Cobas) (D), and GALAD (µTASWAKO) (E). The percentage of participants for each etiology does not sum up to 100% as some patients had multiple etiologies at baseline.

The specificity panel analysis is depicted in Fig. 2c–e. Low profiles of GAAD (Cobas), GALAD (Cobas), and GALAD (µTASWAKO) scores were observed across the disease groups available for analysis (i.e., benign liver cysts, colorectal cancer, Crohn’s disease, other autoimmune diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and ulcerative colitis), with all upper interquartile range values below the established HCC cut-offs, indicating high algorithmic panel specificity for HCC diagnosis.

Clinical performance

Both GAAD (Cobas) and GALAD (Cobas) algorithm scores effectively differentiated between HCC and benign CLD controls, irrespective of HCC disease stage, viral or non-viral etiology, or study center (Fig. 3a–d). The distribution of GAAD and GALAD algorithm scores was similar for both HCC and benign CLD controls, and according to HCC disease stage, etiology, and study center.

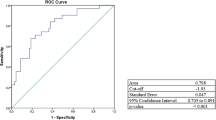

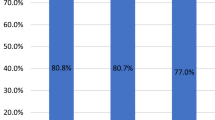

The GAAD (Cobas) and GALAD (Cobas) algorithms demonstrated similar performance in terms of AUC for differentiating between HCC (early-, late- and all-stage) and benign CLD (Fig. 4). For GAAD (Cobas), GALAD (Cobas), and GALAD (µTASWAKO) respectively, AUCs were 93.1% (95% CI: 90.0–96.2), 93.2% (95% CI: 90.0–96.3), and 92.7% (95% CI: 88.4–96.9) for early-stage HCC, 99.7% (95% CI: 99.3–100), 99.7% (95% CI: 99.3–100), and 100% (95% CI: 99.9–100) for late-stage HCC, and 95.6% (95% CI: 93.6–97.6), 95.6% (95% CI: 93.6–97.7), and 95.8% (95% CI: 93.2–98.3) for all-stage HCC, versus benign CLD (Fig. 4a–c). Sensitivity for GAAD (Cobas) and GALAD (Cobas), respectively, was 67.3% and 66.4% for early-stage HCC, 93.9% for both algorithms for late-stage HCC, and 77.3% and 76.7% for all-stage HCC at a specificity of 99.3% for benign CLD (Fig. 4d). For GALAD (µTASWAKO), two cut-offs, − 0.63 and − 1.89 (to mimic 90% specificity with GAAD [Cobas]), were used with respective sensitivities of 56.7% and 68.7% for early-stage HCC, and 68.3% and 78.3% for all-stage HCC, at specificities of 100% and 98.8% for benign CLD, respectively (Fig. 4d). GAAD (Cobas) was non-inferior (within a 1% margin) compared with GALAD (Cobas) and GALAD (µTASWAKO) across HCC stages (p < 0.001).

Clinical performance of GAAD (Cobas) versus GALAD (Cobas and µTASWAKO), vs. three serum biomarkers (AFP, PIVKA-II, and AFP-L3) in HCC in early-stage (A), late-stage (B) and all-stage (C) HCC. Sensitivities and specificities are shown in table (D). *AUC is not significantly worse by 1%. †Cut-off values correspond to the matching GAAD (Cobas) specificity of 90%. AFP alpha fetoprotein, AFP-L3 Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive fraction of AFP, GAAD Gender (biological sex), Age, AFP, PIVKA-II, GALAD Gender (biological sex), Age, AFP-L3, AFP, PIVKA-II, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, PIVKA-II protein induced by vitamin K absence-II, PPV positive predictive value.

The detection of different HCC stages and benign CLD controls using individual biomarkers is shown in Fig. 5. The clinical performance of the GAAD (Cobas), GALAD (Cobas), and GALAD (µTASWAKO) algorithms was generally superior versus the individual serum biomarkers (AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II) alone. When each individual marker was used independently for surveillance, AFP-L3 successfully detected an additional early-stage HCC case that was missed by both AFP and PIVKA-II. Conversely, when AFP and PIVKA-II were combined in an algorithm, GAAD detected six additional early-stage and three additional late-stage HCC cases that were missed by GALAD (µTASWAKO), while displaying the same specificity for the CLD controls (Table 2).

The clinical performance of the different algorithms and individual biomarkers at pre-defined cut-offs is shown in Supplementary Table S2. The clinical performance of the different algorithms and individual biomarkers at specified sensitivities and specificities is shown in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4, respectively. The clinical performance of the GAAD (Cobas) and GALAD (Cobas) algorithms was similar for both HBV and non-HBV etiologies, with or without presence of cirrhosis (Fig. 6a–c). Numerically higher AUCs for both algorithms were observed in the HBV versus non-HBV etiology subset and in the non-cirrhotic vs. cirrhotic subset. For the detection of early-stage HCC, AUCs for GAAD and GALAD were 91.2–94.6% in participants with HBV etiology, and 75.0–80.9% in participants with non-HBV etiologies (Fig. 6a). For the detection of late-stage HCC, AUCs for both GAAD and GALAD were 98.9–100% in participants with HBV, and 79.2–100% in participants with non-HBV etiologies (Fig. 6b). For the detection of all-stage HCC, AUCs for both GAAD and GALAD were 94.3–96.6% in participants with HBV and 79.4–85.7% in participants with non-HBV etiologies (Fig. 6c). The clinical performance of the GAAD (Cobas) and GALAD (Cobas) algorithms was also similar between clinical testing sites in Guangzhou and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of China in early-, late-, and all-stage HCC participants (Fig. 6d–f).

Discussion

The National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China recently updated the guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary liver cancer, stating that the simplified GAAD algorithm demonstrated a similar diagnostic performance to the GALAD algorithm37. However, this has previously not been demonstrated in a Chinese population. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show that the clinical performance of the GAAD (Cobas), GALAD (Cobas), and GALAD (µTASWAKO) algorithms was comparable for the differentiation of HCC from benign CLD in a Chinese subpopulation. The improved clinical performance was also observed regardless of HCC disease stage, disease etiology, or clinical site. Additionally, GAAD (Cobas), GALAD, (Cobas), and GALAD (µTASWAKO) algorithms showed greater sensitivity for HCC across all disease stages when compared with individual serum biomarkers (AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-II) alone. The specificity panel demonstrated that the GAAD (Cobas), GALAD (Cobas), and GALAD (µTASWAKO) algorithms were specific for HCC diagnosis, and that markers were not upregulated in other cancers or benign diseases, therefore indicating an accurate HCC diagnosis. Notably, GAAD detected six additional early-stage and three additional late-stage HCC cases that were missed by GALAD (µTASWAKO). GAAD and GALAD also reported equally high specificities; this is of great clinical relevance indicating that GAAD can serve as an effective surveillance strategy compared with GALAD, while maintaining a low false positive rate that is similar to GALAD.

Since China accounts for almost two thirds of all HCC cases reported in Asia, with an incidence rate of 18.2 per 100,000 population, and a mortality rate of 17.2 per 100,000, early HCC detection in the Chinese population is vital2. As such, the Working Group on Obesity in China recommended lower BMI cut-offs for obesity compared with the World Health Organization. The high prevalence of HBV in China, often acquired through perinatal transmission, significantly contributes to the high incidence of HCC, with more than half of all HCC cases in China reported to have HBV-related etiology7,8. Additionally, the increasing incidence of obesity and obesity-related diseases in China, including MASLD and MASH, further contributes to the high level of HCC observed in this population2,15,16. As the feasibility of curative therapies for HCC is highly dependent on the disease stage at the time of diagnosis, preventative interventions, such as vaccination against HBV and HCC surveillance programs, are crucial22,24,39. Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated the benefit of HCC surveillance among those with chronic HBV in China. One such study that assessed the effectiveness of liver cancer screening in participants with chronic HBV (n = 5,581) in China, found that a higher proportion of those undertaking 6-monthly surveillance with AFP and ultrasound were diagnosed with early-stage liver cancer (29.6%) compared with those undergoing no surveillance (6.0%)40. Similarly, another study of participants with HBV or a history of chronic hepatitis (n = 18,816) in Shanghai found that, despite a low adherence of 58.2%, biannual screening with AFP and ultrasound reduced HCC mortality by 37%41. Furthermore, biannual screening with AFP enabled detection of most HCC tumors at a resectable stage and significantly improved survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years, compared with no surveillance41. Therefore, it is imperative that patients are diagnosed as early as possible to maximize survival outcomes7.

For the detection of early-stage HCC, the GAAD (Cobas) and GALAD (Cobas) algorithms achieved sensitivities of 67.3% and 66.4% (each at specificities of 99.3%), respectively, and the GALAD (µTASWAKO) algorithm displayed a sensitivity of 68.7% (specificity 98.8%) at a cut-off of − 1.89. These data suggest that, as the performance of the GAAD algorithm (without the AFP-L3 serum biomarker) was comparable with the GALAD algorithm (Cobas or µTASWAKO), the incorporation of AFP-L3 into diagnostic algorithms may not be essential for the detection of early-stage HCC.

A reduced number of serum biomarkers needed for a sensitive and specific diagnostic algorithm, as seen with GAAD (Cobas), may be beneficial to healthcare systems. It would require fewer samples and assay workups to achieve the same outcomes, thereby reducing economic burden and assay lead-times42. Multiple studies have also compared the cost-effectiveness of GAAD with other HCC surveillance modalities. One such study found that both GAAD and GALAD combined with ultrasound were cost-effective HCC surveillance strategies compared with ultrasound alone, generating three times the Chinese 2021 gross domestic product per capita for patients with non-cirrhotic chronic HBV43. Additionally, a cost-utility analysis of a simulated cohort of 100,000 participants in the United Kingdom found that GAAD was cost-effective, compared with ultrasound alone and ultrasound combined with AFP measurements, in participants with compensated liver cirrhosis (CLC)44. In those with CLC and viral hepatitis etiology, GAAD remained dominant compared with ultrasound with AFP and more cost-effective than ultrasound alone44. Similarly, a Swiss study demonstrated that GAAD was the most cost-effective surveillance strategy compared with no surveillance, ultrasound alone, and ultrasound with AFP, in participants with CLC, non-cirrhotic fibrosis (stage 3), and non-cirrhotic chronic HBV45.

A large proportion of participants in this study were receiving anti-viral therapy for HBV (total HCC, 63.1%; benign controls, 61.0%), which is concurrent with the endemic nature of the virus within China7,9. It is important to note that elevated AFP serum levels in patients with HBV and HCV, in the absence of HCC, may also occur as a result of the transcriptional upregulation of AFP by the viral transcription co-regulator, HBx33,46. However, falsely elevated AFP in patients with active hepatitis would be minimized with antiviral therapy, through suppressing the mechanisms of viral replication, subsequently reducing inflammatory damage33,47. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that a lower cut off for AFP displays high sensitivity for the detection of HCC among patients with HBV receiving anti-viral treatment33,47. Therefore, the addition of AFP to surveillance can further improve HCC detection in participants with HBV/HCV receiving antiviral therapies33. Considering this, further research incorporating additional populations is needed to clarify how each individual serum biomarker contributes to the performance of the GAAD and GALAD algorithms, accounting for disease etiology and any ongoing antiviral or other medical treatments.

Limitations

Despite national vaccination programs, the majority of participants with HCC included in this Chinese study had viral-related etiology. This was expected as previous studies have shown that China has high rates of HBV and HCV, which account for 60% of HCC cases7. Although good clinical performance was observed across disease etiologies in our study, the limited numbers of participants with non-viral etiologies should be considered. However, the clinical validation of GAAD has been investigated in a larger cohort of patients with non-viral etiologies across the Asian-Pacific region and Europe with findings that support the results of the present study36. Another limitation of this study was the small sample sizes for disease groups in the specificity panel, which limited the number of disease groups with sufficient samples for analysis.

Conclusions

Here, we show that GAAD and GALAD algorithms display similar clinical performance for the differentiation of benign CLD and HCC, irrespective of HCC disease stage, underlying etiology, or clinical study site. These findings suggest that the GAAD (Cobas) algorithm may be an efficient diagnostic tool in the surveillance of high-risk patients with CLD, including those with HBV, and could contribute to earlier HCC diagnoses, and therefore improved HCC outcomes.

Data availability

Requests concerning the data supporting the findings of this study can be directed to the corresponding author, Dr Ashish Sharma, or rotkreuz.datasharingrequests@roche.com for consideration.

References

Rumgay, H. et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J. Hepatol. 77, 1598–1606 (2022).

Zhang, C. H., Cheng, Y., Zhang, S., Fan, J. & Gao, Q. Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Liver Int. 42, 2029–2041 (2022).

Ma, T., Wei, X., Wu, X. & Du, J. Trends and future projections of liver cancer incidence in Hong Kong: a population-based study. Arch. Public Health 81, 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-023-01191-3 (2023).

Chan, W. K. et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD): a state-of-the-art review. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 32, 197–213 (2023).

Yang, J. D. et al. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 589–604 (2019).

Zhu, B. et al. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 742382. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.742382 (2021).

Llovet, J. M. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 7, 6 (2021).

Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration. The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: results from the global burden of disease study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 3, 1683–1691 (2017).

Wang, C. & Cui, F. Expanded screening for chronic hepatitis B virus infection in China. Lancet Global Health 10, e171–e172. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00547-7 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Hepatitis B infection in the general population of China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4428-y (2019).

Tu, T., Budzinska, M. A., Shackel, N. A. & Urban, S. HBV DNA integration: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Viruses 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/v9040075 (2017).

Rizzo, G. E. M., Cabibbo, G. & Craxì, A. Hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinomaa. Viruses 14 (2022).

Ali, A. et al. Hepatitis B virus, HBx mutants and their role in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 20, 10238–10248. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i30.10238 (2014).

Sivasudhan, E., Blake, N., Lu, Z., Meng, J. & Rong, R. Hepatitis B viral protein HBx and the molecular mechanisms modulating the hallmarks of hepatocellular carcinoma: a comprehensive review. Cells 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11040741 (2022).

Wong, V. W. S., Ekstedt, M., Wong, G. L. H. & Hagström, H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J. Hepatol. 79, 842–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036 (2023).

Fan, J. G., Kim, S. U. & Wong, V. W. S. New trends on obesity and NAFLD in Asia. J. Hepatol. 67, 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.003 (2017).

Liu, L., Li, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. & Cao, Z. Hepatitis B virus infection combined with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Interaction and prognosis. Heliyon 9, e13113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13113 (2023).

Xie, D. Y., Ren, Z. G., Zhou, J., Fan, J. & Gao, Q. 2019 Chinese clinical guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: updates and insights. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 9, 452–463. https://doi.org/10.21037/hbsn-20-480 (2020).

Llovet, J. M. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2, 16018. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.18 (2016).

Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1450–1462. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1713263 (2019).

Calderon-Martinez, E. et al. Prognostic scores and survival rates by etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review. J. Clin. Med. Res. 15, 200–207. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr4902 (2023).

Omata, M. et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 update. Hepatol. Int. 11, 317–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9 (2017).

Vogel, A. et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 29, iv238–iv255. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy308 (2018).

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2023—hepatocellular carcinoma. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/hcc.pdf (2023).

Piñero, F., Dirchwolf, M. & Pessôa, M. G. Biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis, prognosis and treatment response assessment. Cells 9, 1370. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9061370 (2020).

Piratvisuth, T. et al. Multimarker panels for detection of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective, multicenter, case–control study. Hepatol. Commun. 6, 679–691. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep4.1847 (2022).

Guan, M. C. et al. The performance of GALAD score for diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Med. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12030949 (2023).

Berhane, S. et al. Role of the GALAD and BALAD-2 serologic models in diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and prediction of survival in patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14, 875–886e876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.042 (2016).

Johnson, P. J. et al. The detection of hepatocellular carcinoma using a prospectively developed and validated model based on serological biomarkers. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 23, 144–153. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0870 (2014).

Best, J. et al. GALAD score detects early hepatocellular carcinoma in an international cohort of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 728–735. .e724 (2020).

Singal, A. G. et al. GALAD demonstrates high sensitivity for HCC surveillance in a cohort of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology (Baltimore Md) 75, 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.32185 (2022).

Xie, D. Y. et al. A review of 2022 Chinese clinical guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: updates and insights. Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 12, 216–228. https://doi.org/10.21037/hbsn-22-469 (2023).

Qian, X. et al. Reappraisal of the diagnostic value of alpha-fetoprotein for surveillance of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of antiviral therapy. J. Viral Hepat. 28, 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13388 (2021).

Qian, X. et al. The performance of serum alpha-fetoprotein for detecting early-stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma is influenced by antiviral therapy and serum aspartate aminotransferase: a study in a large cohort of Hepatitis B Virus-infected patients. Viruses 14, 1669 (2022).

Yang, J. D. et al. Improved performance of serum alpha-fetoprotein for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis in HCV cirrhosis with normal alanine transaminase. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 26, 1085–1092. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.Epi-16-0747 (2017).

Piratvisuth, T. et al. Development and clinical validation of a novel algorithmic score (GAAD) for detecting HCC in prospective cohort studies. Hepatol. Commun. 7. https://doi.org/10.1097/HC9.0000000000000317 (2023).

National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines for primary liver cancer. http://www.nhc.gov.cn/cms-search/downFiles/48cd549a54204ab1a6247e86adb2dea2.pdf (2024).

Hou, J. et al. Comparative evaluation of multimarker algorithms for early-stage HCC detection in multicenter prospective studies. JHEP Reports (Manuscript Accepted).

Liu, Z. et al. Impact of the national hepatitis B immunization program in China: a modeling study. Infect. Dis. Poverty 11, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-022-01032-5 (2022).

Chen, J. G. et al. Screening for liver cancer: results of a randomised controlled trial in Qidong, China. J. Med. Screen. 10, 204–209. https://doi.org/10.1258/096914103771773320 (2003).

Zhang, B. H., Yang, B. H. & Tang, Z. Y. Randomized controlled trial of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 130, 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-004-0552-0 (2004).

Liu, S. et al. Diagnostic performance of AFP, AFP-L3, or PIVKA-II for hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter analysis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 5075 (2022).

Chen, W. et al. EE85 cost-effectiveness analysis of GAAD algorithm on the detection of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease in China. Value Health 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2022.09.337 (2022).

Garay, O. U. et al. Cost-effectiveness of HCC surveillance strategies in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis in the United Kingdom Value Health Article in press (2024).

Goossens, N. et al. Cost-effectiveness of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) Surveillance Strategies in Switzerland. Swiss Med. Wkly. 153, 6. https://doi.org/10.57187/s.3511 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Alpha fetoprotein mediates HBx induced carcinogenesis in the hepatocyte cytoplasm. Int. J. Cancer 137, 1818–1829. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29548 (2015).

Wong, G. L. et al. On-treatment alpha-fetoprotein is a specific tumor marker for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving entecavir. Hepatology (Baltimore Md). 59, 986–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26739 (2014).

Acknowledgements

Editorial support for this manuscript, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Holly McAlister, MSc, and Jade Drummond, BSc, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare Ltd, UK, and was funded by Roche Diagnostics Ltd (Rotkreuz, Switzerland). GAAD is a CE-marked digital tool for aid in diagnosis of early-stage HCC. ELECSYS and COBAS are trademarks of Roche. All other product names and trademarks are the property of their respective owners.

Funding

This study was funded by Roche Diagnostics GmbH (Penzberg, Germany).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; or have drafted the work and substantially revised it, and all authors have approved the submitted version. All authors are accountable for their contributions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

HLYC reports consultancy fees from Arbutus Biopharma, Gilead Sciences, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Roche, Vir Biotechnology, Aligos Therapeutics, Vaccitech, and Virion Therapeutics; and speaker’s bureau participation for Echosens, Gilead Sciences, Roche, and Viatris. YH has no conflicts of interest to declare. KMad, KK, and AS are employees of Roche Diagnostics International AG. KMal is an employee of Microcoat Biotechnologie, contracted by Roche Diagnostics. JH reports speaker’s bureau participation for Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Gilead Sciences, and Roche Diagnostics; has received grant/research support from Gilead Sciences and BMS; and has served on an advisory committee or review panel for Aligos, Assembly, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Gilead Sciences, Johnson Pharmaceutica, and Roche.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chan, H.L.Y., Hu, Y., Malinowsky, K. et al. Prospective appraisal of clinical diagnostic algorithms for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Sci Rep 14, 28996 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80257-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80257-w