Abstract

Cervical cancer is one of the biggest challenges in global health, thus it forms a critical need for early detection technologies that could improve patient prognosis and inform treatment decisions. This development in the form of an early detection mechanism increases the chances of successful treatment and survival, as early diagnosis promptly offers interventions that can dramatically reduce the rate of deaths attributed to this disease. Here, a customized Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model is proposed for cervical cancerous cell detection. It includes three convolutional layers with increasing filter sizes and max-pooling layers, followed by dropout and dense layers for improved feature extraction and robust learning. By using ResNet models as inspiration, the model further innovates by incorporating skip connections into the CNN design. By enabling direct feature transmission from earlier to later layers, skip links enhance gradient flow and help preserve important spatial information. By boosting feature propagation, this integration increases the model’s ability to recognize minute patterns in cervical cell images, hence increasing classification accuracy. In our methodology, the SIPaKMeD dataset has been employed which contains 4049 cervical cell images that are arranged into five different categories. To address class imbalance, Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) have been applied for data augmentation; that is, synthetic images have been created, that improve the diversity of the dataset and further enhance the robustness of the same. The present model is astonishingly accurate in classifying five cervical cell types: koilocytes, superficial-intermediate, parabasal, dyskeratotic, and metaplastic, thus significantly enhancing early detection and diagnosis of cervical cancer. The model gives an excellent performance because it has a validation accuracy of 99.11% and a training accuracy of 99.82%. It is a reliable model in the diagnosis of cervical cancerous cells because it ensures advancement in the computer-assisted cervical cancer detection system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cervical cancer remains a major worldwide health issue, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where access to early detection and treatment options may be limited. Early and accurate diagnosis of cervical cancer is crucial for reducing mortality rates and improving patient outcomes. Traditional methods, such as Pap smears, have been widely used for screening, but they often rely on manual analysis, which can be tedious and susceptible to human error. New developments in artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning (DL) offer promising solutions for the classification automation of cervical cells, enhancing both the speed and accuracy of diagnosis.

Several studies have demonstrated the potential of Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for cervical cancer classification. For instance, authors of1 and2 explored fully automated DL pipelines, achieving robust results in the detection and classification of cervical cancerous cells. Similarly, other researchers have integrated machine learning and DL techniques, such as in3, which combines CNN with extreme learning machines, and4, which applied deep learning algorithms to categorize CC cells. While these studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of CNNs in medical image analysis, they frequently encounter difficulties. such as class imbalance, limited dataset sizes, and the need for advanced architectures to improve performance.

In response to these challenges, this research proposes an integrated approach for classifying cervical cancerous cells into five distinct categories—superficial-intermediate, parabasal, koilocytotic, metaplastic, and dyskeratotic—using a customized CNN model with skip connections and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). Skip connections, inspired by ResNet architectures5,6, enable better feature propagation by allowing information to flow across layers without degradation. This mechanism improves the learning of subtle patterns within the cell images, thereby enhancing classification accuracy. To deal with the imbalance issue, GANs are employed to generate synthetic images for underrepresented categories, enriching the dataset and improving model robustness7,8.

By combining these advanced techniques, this study builds upon the foundational work in cervical cancer classification, aiming to overcome existing limitations and provide a more reliable, efficient system for early cancer detection. The proposed approach exhibits the capacity to notably aid in clinical decision-making by offering a more accurate and automated solution for identifying different types of cervical cells, ultimately contributing to better patient outcomes.

CNN is a DL technique, which provides a revolutionary way to enhance cervical cancer diagnosis9. CNNs specialize in image recognition and extraction of characteristics; therefore, they become suitable for medical imaging-oriented tasks10,11. The accuracy of diagnosis can be increased, and subjectivity can be reduced, by automatic recognition of complex image patterns of cervical cells through CNNs. Further, the introduction of a Skip mechanism has been beneficial in CNN models12. Skip connections can help maintain essential features and maintain the flow of information that gets lost as the information escapes specific network layers, maintaining features important for classification. Generative Adversarial Networks are used for the addition of synthetic images in medical datasets to rectify class imbalances. This approach improves the generalizability of the model since13,14, by generating new realistic images that will equilibrate underrepresented groupings, it maintains correct functionality across all categories.

The main contributions made by this study are:

-

(1)

The study implements a thorough pre-processing pipeline that organizes, resizes, adds borders, and applies blurring to standardize the images, ensuring they are uniformly formatted before being input into the deep learning model. Additionally, GANs are used for data augmentation, particularly to address class imbalance by generating synthetic images for underrepresented cervical cell categories.

-

(2)

A customized CNN model was designed specifically for this study. It includes three convolutional layers with increasing filter sizes and max-pooling layers, followed by dropout and dense layers for improved feature extraction and robust learning.

-

(3)

By using ResNet models as inspiration, the study further innovates by incorporating skip connections into the CNN design. By enabling direct feature transmission from earlier to later layers, skip links enhance gradient flow and help preserve important spatial information. By boosting feature propagation, this integration increases the model’s capacity to identify minute patterns in cervical cell pictures, hence increasing classification accuracy.

-

(4)

Training two models (a baseline CNN and a CNN with skip connections) in parallel allows for a direct comparison, helping to identify which architecture performs better. This approach makes it easier to assess the benefits of skip connections and speeds up the process of refining and improving the models.

Literature review

A considerable amount of research in this rapidly growing field of cancer diagnosis has been conducted in the past few years. This section describes previous work in CC detection, ranging from simple image processing and classification techniques to AI-infused algorithms. In15, authors propose a CNN-based classification of cervical cells with the SIPaKMeD dataset, which consists of five classes, namely superficial-intermediate, parabasal, koilocytotic, metaplastic, and dyskeratotic, are used. The application of CNN with four convolutional layers to the segmented and augmented Pap smear images gives an accuracy of 91.13%, efficiently classifying the cells as healthy, precancerous, or benign. Thus, the ResNet50V2 model was used as the backbone of the system structure, and its performance has been successfully tested. The research carried out by16, employed CNN with training loss (TL), namely, MobileNet, NasNetLarge, Densenet201, and InceptionResNetV2, for classifying cervical cells into five groups against the SIPaKMeD dataset. The outcomes showed how these methods improved accuracy in classification, where the best accuracy at 92% was obtained by InceptionResNetV2. These results are pointing out that with such TL-based CNN methods, it is possible to provide a more precise and trustworthy CC screening method. The authors of17 evaluated a transfer learning model on a publicly available dataset of 917 images of the uterine cervix improved by histogram equalization and denoised using a Gaussian filter. The VGG19 model has performed far better than the others with an accuracy rate of 98.26% and achieved very good outcomes for all performance measurements. Their research demonstrated a good performance of the VGG19 model with Gaussian filtering and histogram equalization for CC diagnosis. The aim of the research of18 was to employ a DNN with optimized transfer learning to categorize the three types of cervixes of patients with CC. The model was pretrained on the ImageNet Challenge using pre-computed activations from the ResNet architecture and InceptionV3. The dataset, which came from a Kaggle challenge, had 6734 extra training images in addition to 1481 train and 512 test images. Techniques for image enhancement were used because of the small dataset. With an accuracy of 72% on the test set, the model that used ResNet’s previously trained weights with top-down enhancements proved to be the most effective among the models that were tested using both augmented and non-augmented data. A CC cell identification and classification method utilizing CNN is presented in the paper5. The system uses a CNN model that is improved by transfer learning and fine-tuning to extract deep-learned features from cell pictures. The paper also looks at classifiers based on autoencoders (AE) and multi-layer perceptrons (MLP) as alternatives to ELM. The CNN-ELM-based system obtained 99.5% accuracy for the detection task (2-class) and 91.2% accuracy for the classification challenge (7-class) in experiments carried out with the Herlev database. The goal of the study conducted by19 is to create an AI image detection system that employs the Bethesda classification to identify lesions related to cervical cancer in liquid-based Pap tests. Six main tasks were included in the study: choosing a dataset, augmenting the data, optimizing, creating models, testing them, and building the finished system. Using Pap smear photos that were made available to the public, a dataset of 2,676 images was produced and improved by data augmentation. The ResNet50V2 and ResNet101V2 models were created utilizing TL and DL methods. The analysis showed that the ResNet50V2 model outperformed the others, with an overall accuracy of 0.97 and precision of 0.98 for HSIL and SCC classifications. The ResNet50V2 model was used in the construction of the finished system, and its functionality was successfully verified. To solve the limited dataset issue in cervical cell/clumps identification tasks when utilizing deep learning methods, this work suggests utilizing COCO pre-trained models by the authors of20. Based on the features of the dataset, multi-scale training was carried out to improve detection performance. The study also looked at how different bounding box loss functions affected the precision of the model and discovered that performance is improved when the loss function used is in line depending on the kind of pre-trained model. The findings indicated that the cervical cell dataset’s mean and std produced the best detection outcomes. The model ultimately produced mean Average Precision (mAP) of 61.6% and an Average Recall (AR) of 87.7% with a ResNet50 backbone. These results indicate notable gains over the prior values of 48.8% and 64.0% on the same dataset, of 12.8% in mAP and 23.7% in AR. The goal of the research21 is to apply TL to create an automated system that can recognize the two kinds of CC from histopathology images: cervical squamous cell carcinoma and cervical adenocarcinoma. TL is becoming more and more successful in DL, and this work uses 59 high-resolution whole slide images (WSIs)—45 of which were utilized for training and 14 for testing—to categorize cervical histopathology. The suggested model’s 85% accuracy and 86% AUC score show how useful TL is in this newly developed field of cervical cancer detection. PsiNet-TAP, a unique network created to categorize Pap smear images, is introduced in the study22. To create a pre-trained model, TL was used because there weren’t many photos accessible. After that, the convolution layer was changed, and specific convolution kernels that might have interfered with the classification task were pruned, to optimize the model. With an accuracy of more than 98%, PsiNet-TAP demonstrated impressive performance in testing on 389 cervical Pap smear images. This indicates that the approach is a useful tool for classifying CC in clinical settings. The authors of23 propose a fully automated novel approach in the categorization of CC through the integration of ensemble learning, TL, and the transformer encoder-ViT. High accuracy potential is realized with high clinical diagnostic applicability since it succeeds in reducing human participation in the methodology. Cervical cells of five different types are classified under the VGG16 model at an accuracy of 97.04% and an F1 score of 97.06%. It has been found that the Ensemble Learning Model has an accuracy of 97.37%, which is a modest performance increase. The Transformer Encoder Model, with an accuracy of 97.54%, beats all other models and demonstrates the potential of transformers for the categorization of medical scans. In24, the proposed classification of cervical cells into five groups with the help of different CNN architectures has used the same dataset, which is SIPaKMeD. Among all models evaluated, this VGG16 architecture with the Squeeze-and-Excitation Network module returned an accuracy of 96.57% in classification. The current research shows that among the useful strategies to enhance the performance of categorization of a CNN for tasks in medical image analysis is using attention modules like SENet. The Deep Integrated Feature Fusion (DIFF) block was used by the authors of25 to merge local and global characteristics of cytology images from a CNN branch and a transformer branch. They made use of information from four datasets: 917 photographs from Herlev, 4789 images from CRIC, and 4049 shots from SipakMed. They achieved 96.02% accuracy and 96.09% precision on the SipakMed dataset. Recall: 96.04%; F1-Score: 96.04%. They achieved 85.06% accuracy on the CRIc dataset. 85.12% F1-score, 85.47% recall, and 85.23% accuracy. 94.55% of the Herlev dataset is accurate. 94.13%, 91.66%, and 92.78% F1-score accuracy. By combining information from each module through weighted voting, the system of26 achieves very accurate cancer cell detection. On the Mendeley dataset, IATS outperformed 25 other deep learning models, including CNNs and Vision Transformers, with an accuracy of 98.44%, and on the SIPaKMeD dataset, 55.68%. By lowering the probability of misdiagnosis, this indicates a 2.5% accuracy gain over the top CNN model on the Mendeley dataset, suggesting potential to transform cervical cancer screening. An image-based Transformer model for CC classification in pap smears, called CerviFormer, is presented in the study of27. CerviFormer efficiently handles massive inputs while imposing the fewest possible architectural constraints by leveraging cross-attention. Based on evaluations using the Sipakmed dataset for 3-state classification and the Herlev dataset for 2-state classification, the model obtained 96.67% and 94.57% accuracy, respectively. According to the results, CerviFormer offers comparative performance compared to existing procedures. In a novel architecture, three pre-trained models for CC prediction are aggregated via a fuzzy rank-based ensemble with non-linear functions 28. The model uses complex augmentation techniques including CutOut, MixUp, and CutMix. It was tested using fivefold cross-validation on the SIPaKMeD and Mendeley LBC datasets. It obtained 97.18% accuracy and 97.16% F1 score on SIPaKMeD and 99.22% accuracy and 99.19% F1 score on Mendeley LBC.

While many studies15,16,23,25,28 address the issue of class imbalance through data augmentation techniques, there is still a reliance on relatively small datasets like SIPaKMeD and others. Many existing models achieve high accuracy but may not be generalizable due to overfitting on these limited datasets. Although various studies5,19,20,21,22 have utilized established CNN architectures and transfer learning, there is a lack of exploration into the integration of newer techniques such as hybrid models combining different deep learning approaches. For instance, while some studies have explored the use of transformers or ensemble methods, there is potential for more comprehensive integration of diverse architectures (e.g., CNNs combined with skip connections or recurrent neural networks) to improve classification performance34. This study concentrates on an integrated CNN model with Skip connections and GAN mechanism for the classification of the CC into five distinct classes.

Material and methods

Dataset description

Cervical cancer, which continues to be the cancer that affects women the most frequently worldwide with over 0.53 million new cases and over 0.28 million deaths yearly, requires the use of the SIPaKMeD dataset 29. This dataset makes a substantial contribution to the important task of early detection. It includes 4049 images of single cervical cells that were carefully clipped from 966 images of cluster cells from Pap smear slides. These images were captured with an optical microscope equipped with a CCD camera, guaranteeing crisp, detailed photographs. The dataset provides a complete picture of healthy, precancerous, and non-cancerous but atypical cells, divided into different cell types: normal, aberrant, benign, and cancerous. This category is crucial for creating and assessing DL models that automate the identification and categorization of CC 30, which is why it is so important for clinical practice. The five main kinds of cervical cells, included in the SIPaKMeD dataset of this investigation, are (Fig. 1):

-

1.

Superficial-intermediate: These are the normal cells shown in Fig. 2a that are found on the surface of the cervix and in the intervening layers. Usually, they are thought to as non-cancerous and are indicative of either a healthy or little altered cervical epithelium7.

-

2.

Parabasal: These cells, which are shown in Fig. 2b situated in the deeper layers of the cervix, are also normal8. These cells can arise as a result of hormonal fluctuations or other benign circumstances occurring in the body.

-

3.

Koilocytes: The cells shown in Fig. 2c are linked to human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, koilocytes are non-cancerous abnormal cells. These exhibit characteristic changes, like a perinuclear halo, and are significant warning signs of dysplasia linked to HPV9.

-

4.

Dyskeratotic: The cell shown in Fig. 2d are abnormal cells that are typically associated with dysplasia or malignancies10. They are a critical marker of cervical lesions in their initial phases and show significant levels of keratinization.

-

5.

Metaplastic: The cells shown in Fig. 2e are the results of an epithelial cell’s conversion into a dissimilar type. Although metaplastic cells often do not indicate malignancy11, they can be a sign of persistent variations in the cervical epithelial tissue.

Distribution of the class-wise images29.

The Sample images for class29 (a) Superficial-Intermediate (b) Parabasal (c) Koilocytotic (d) Dyskeratotic (e) Metaplastic.

Figure 1 gives the distribution of images class-wise in the dataset. Figure 2 displays the sample images for the above-mentioned classes of the dataset. From the figure, it can be seen that Metaplastic and Parabasal classes have less number of images than other classes.

Pre-processing

The images are passed through various pre-processing steps to remove any redundancy and noise from the images. The pre-processing steps involve 6 steps of organizing the dataset, resizing images, adding borders, blurring them, and saving them in a new format. These steps are essential for standardizing the input images before they are fed into a DL model for the classification of images31. Figure 3 gives the pre-processing steps flow followed to prepare the dataset for model training. The very first step is to collect the CC data from the SIPakMeD dataset. This includes making specific directories for every class, and are downsized to 256 by 256 pixels, and a 1-pixel black border added. After that, a 2 × 2 kernel is used to blur the image. This stage improves the image for subsequent processing32 by smoothing it out and lowering noise33 and then the modified images are subsequently stored in the appropriate destination directories as.jpg files .

The dataset has an imbalanced distribution among the classes: metaplastic (793 images), koilocytes (825 images), dyskeratotic (813 images), parabasal (787 images), and superficial-intermediate (831 images). However, the individual class sizes suggest the potential for imbalance, especially for metaplastic cells, which could benefit from additional synthetic samples to enhance classification performance. The relatively small overall dataset size makes it an ideal candidate for GAN augmentation, as generating synthetic images can significantly expand the available training data without the need for extensive manual data collection. Additionally, the natural variability in cervical cell characteristics—such as shape, size, and texture—can be effectively captured and replicated by GANs, leading to the generation of realistic images that improve the diversity of the dataset. This enhancement helps to reduce overfitting and improves the model’s ability to generalize, ultimately boosting performance in identifying and classifying cervical cells. Furthermore, the incorporation of GAN-generated images can aid in addressing the challenges associated with class imbalance, thereby enhancing the robustness and reliability of deep learning models applied to cervical cancer detection.

Next, the images are passed for normalization in which the images are scaled in the range of [0,1]. This step ensures that the similarity of scale of all input attributes. Because of its ability to process input with consistent features, the GAN’s generator and discriminator can train more efficiently. In this step, the images are shuffled to rearrange the images inside a dataset is to guarantee that the model does not acquire any inadvertent patterns or prejudices associated with the data’s arrangement, as this may have an adverse effect on the model’s efficacy and applicability. The splitting of the dataset into three sets of train, test and validation in the ratio 7:1.5:1.5, which means 70% of images are allocated for training and 15% of data is allocated for both test and validation set. These sets will further help in train, test and validation of the proposed framework.

Proposed methodology

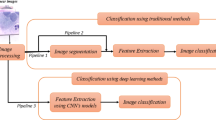

The proposed methodology is divided into three sections firstly a customized CNN model will be designed, secondly, a CNN model with Skip connection will be developed, thirdly both the models will be trained and further validated with the implication of train and validation set, lastly, best model selection for the classification of CC cells into five classes will be done. Step by step description will be discussed in this section.

Designing a customized CNN model

When constructing a CNN model, the main objective is to create a strong and resilient model that can efficiently learn and generalize features from input images. Figure 4 showcases the CNN model architecture. The figure shows that the first layer of the model is the input layer, which takes 256 × 256 resolution images with three color spaces called RGB channels. Three convolutional blocks consisting of convolutional layers with ReLU activation and increasingly larger filter sizes of 32, 64, 128 have been used. These building pieces are essential for extracting patterns and spatial hierarchy from the input data. MaxPooling layers are purposefully arranged to trail each block to reduce spatial dimensions and minimize computing complexity without sacrificing important features. The dropout layer has been incorporated to increase the model’s robustness and guard against overfitting. Dropout is a training strategy where certain input units are arbitrarily set to zero. This improves the network’s ability to generalize by encouraging it to gather redundant representations. The final stage involves flattening the convolved features and passing them through two dense layers, each with 128 units. A dense layer with five units follows, which is activated by softmax to aid with classification. This CNN architecture is ideal for tasks requiring accurate feature extraction and classification since dropout and careful component selection ensure an appropriate balance between the level of model complexity along generalization.

Designing a customized CNN model integrated with skip mechanism

This study focuses on classifying cancer cervical cells into five distinct classes. This step of the proposed framework includes integrating the skip mechanism with the customized CNN model to enhance its classification qualities. Skip connections, which are also referred to as shortcut connectors or residual connections, enable a layer’s output to be added directly to the output of a succeeding layer, eliminating the need for one or more intermediate layers. ResNet is the most well-known application of this idea. Here in this study, skip connection is integrated with CNN to improve the gradient flow and for better feature propagation. To maintain spatial information, skip connections enable features from previous layers to be transferred directly to later layers. Figure 5 gives the proposed structure of the CNN model integrated with the Skip mechanism.

From Fig. 5, it can be seen that there are three convolutional blocks with MaxPooling2D and Conv2D layers that make up the CNN model. The first and third Conv2D blocks are connected via a skip link. The skip connection keeps early layer features, improving the model’s learning capabilities, by adding the output of the first and third convolutional blocks. This operation is performed in the adding layer, then the output of this is forwarded to the dropout layer and further, the flatten layer creates a 1D vector out of the combined feature map to make it ready for the fully connected layers.

Framework designing

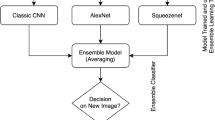

The comprehensive proposed structure created to carry out this classification process is covered in this part. The proposed flow of stages taken to design the framework is shown in Fig. 6. A thorough method for identifying cervical cells from Pap smear images using two different CNN architectures is shown in the flowchart. The first step of the procedure is data collection, which involves gathering images of cervical cells and Pap smears from the SIPakMeD dataset. This dataset comprises of 4049 images of cervical cells for cell types: normal, aberrant, benign, and cancerous. Thus, this dataset has worked as a foundation for conducting this classification task. The next step is the data-processing, this step ensures that the data is in its proposer form for effective model training. This step entails the following crucial actions of the organization of the dataset, wherein the images are arranged, and labeled to facilitate efficient processing. Then the resizing of images is done to provide consistent dimensions throughout the collection. The images are resized to 256 × 256 resolution. Then normalization is conducted, by adjusting the pixel values, this ensures that model training can be completed more quickly and accurately. Furthermore, data augmentation is carried out utilizing GANs to artificially expand the amount and variety of the dataset, thus augmenting the resilience of the model. To maintain randomness and stop the model from picking up any unintentional biases, the images are additionally shuffled. The dataset is now split into training, validation, and testing sets so that the model’s performance may be assessed at various phases. Creating two CNN architectures is the central component of the process.

The first step is to design a customized CNN model which will work as a baseline model for comparison and in the next step this CNN architecture is designed while integrating Skip Connections to preserve important features by appending outputs from previous layers to subsequent ones. Through rigorous training and validation, both models acquire the ability to recognize patterns in the data. To maximize the model’s performance, hyperparameters including a 64-batch size, 0.0001 learning rate, 0.45 dropout rate, Adam optimizer, and sparse categorical loss function are carefully adjusted throughout this phase. The batch size of 64 has been used and it is an example of the tradeoff between computational effectiveness and the ability to capture sufficient patterns in the data. Thus, the model gets a chance to try to change its weights more often without overloading its memory. The learning rate of 0.0001 has been used with the optimizer to make the learning procedure smooth during the training phase so that the model can learn effectively. The dropout rate of 0.45, which means that randomly 45% of neurons are dropped out at training time, is used to avoid overfitting and hence make the model generalize better on unseen input. Then, for the optimizer, Adam with its adaptive learning rate capabilities in that the learning rates change dynamically depending on the gradients will ensure effective convergence. Finally, the sparse categorical loss function has been employed, which works very well in handling multi-class classification problems, especially in the case of sparsely populated category labels. It improves the model’s ability to handle complex patterns hidden within the data; therefore, tuning these hyperparameters increases model robustness and accuracy for the classification of cervical cells. Finally, the designed models are tested on untested data for generalization, and the one that generalizes the best is deployed as final. In this study, cervical cells were further distinguished into five groups—koilocytes, superficial-intermediate, parabasal, dyskeratotic, and metaplastic using the selected model. The first architecture integrates skip connections, which is a major advance in cervical cancer cell classification automation for more accurate and effective diagnosis, as it improves the retention of important features for this architecture and might lead to improved classification accuracy compared to the standard CNN.

Results and discussion

The different performance metrics that were noted during the training and testing of both the models are covered in this section. These findings will also contribute to determining the most effective model for grouping cervical cancer cells into five categories.

Graphical presentation of CNN model accuracy and loss

In this part, the results obtained during the CNN model will be discussed achieved during training, validation and testing of the framework. The model is trained for 25 epochs during which various hyperparameters were tuned to obtain the best classification results. The Sparse Categorical Cross-Entropy Loss has been utilized for training, which is particularly effective for multi-class classification tasks where labels are provided as integer class indices. The loss function is defined as:

where N is the number of samples; xi is the true class label; \((\widehat{{x}_{i}}\),\({x}_{i}\)) is the predicted probability of true class for every sample

As training progresses, the loss values typically decrease from high initial values, indicating the model’s learning efficiency. To prevent overfitting, several strategies were employed, including regularization techniques like L2 regularization, the use of dropout layers, and early stopping based on validation loss. Additionally, data augmentation methods were applied to increase the dataset’s variability, while a train-validation split ensured the model’s performance was continually assessed on unseen data.

Figure 7 displays the graphical presentation of Model Accuracy and Loss measured during training and validation of the model. The red curve in Fig. 7a represents the training accuracy (TA), which initially increases rapidly to indicate that the model is selectively acquiring new knowledge from the training data. The graph exhibits a peak at epoch 10, suggesting that the model has effectively achieved its highest level of training accuracy and has successfully identified the bulk of the patterns present in the data. As the training continues a smooth increase in the TA is visible without any major drop, this signifies that the model is learning the features of the images. The model achieved a TA of 99.89%. The green-colored curve of the validation accuracy illustrates the performance of the model on validation data. The VA rapidly increases during the initial epochs and thereafter reaches a stable state, consistent with the training curve, indicating that the model is effectively generalizing to novel data. The presence of a blue dot at epoch 17 signifies the optimal point at which the model achieved its highest level of accuracy on the validation set, marking the highest level of validation accuracy. From Fig. 7a the smooth increase in the values of both accuracies can be noticed. The model reached 98.07% validation accuracy at the end of the 25th epoch. A successful training process has been confirmed by the model’s high validation accuracy, which suggests that the training was successful.

The close alignment of the curves for training and validation accuracies indicates that the model is keeping an ideal balance between learning and generalization. The graph shows overall that the model is strong, showing good performance on datasets used for both training and validation as well as efficient generalizing to fresh data.

The plot of Fig. 7b showcases the model loss for both training and validation. This graph demonstrates a steady decrease in the training loss (TL) of the model, implying that it is progressively learning fresh skills and fitting the training set. As the epochs pass, the model keeps its capacity to reduce the error to its minimum value of 0.0012 on the training set by proving a strong awareness of the fundamental trends in the data. The validation loss (VL) which is an indicator of the model’s performance on untested data, declines in the first few epochs, signifying that the model is generalizing well beyond the training set. The VL dropped to 0.102 at the end of the 25th epoch. Based on this stability, the model has hit the perfect mix between maintaining generalization with newly acquired data and matching the training set.

Figure 8 displays the confusion matrix recorded during the testing of the model on the test dataset. Since it offers a thorough understanding of how well a classification model is working over several classes, the confusion matrix is a great instrument for assessing its performance. The diagonally distributed components of the matrix, which extend from the top-left to the bottom-right corners, indicate the proportion of precise predictions the model produced for each class. The numbers on the diagonal in this case indicate how many samples from each of the five classes 80, 83, 80, 81, and 74 were successfully identified. Other components of the matrix indicate the wrong predictions made by the model. From the figure, it can be seen that out of 408 test images, 400 images were correctly predicted. This shows that the model is performing well on the unseen data and is classifying the cell’s images effectively into five classes.

Table 1 describe the various performance measures on the test dataset used to evaluate the performance of the model. Across five separate classes (labeled 0 to 4), the table aggregates the accuracy, recall, precision, and F1-score of a classification model. The number of true positive predictions among all the positive predictions generated by a model defines its precision. From the table, it can be concluded that for Class 0 precision is 98.17%, which signifies that the model has correctly predicted 80 images for Class 0. Likewise for Class 1, 83 images, 81 images for Class 2 and Class 3 whereas 75 images for Class 4 have been correctly predicted.

The percentage of accurate positive forecasts among all real positives is known as recall. It shows how successful the model is at locating every instance of a specific class. The percentage of accurate positive forecasts among all real positives is known as recall. It shows. The model has shown great Recall value for all classes which indicates how successful the model is at locating every instance of a specific class. The F-1 Score is a statistic that provides a balance between Precision and Recall, calculated as the harmonic mean of these two performance parameters. A greater F-1 Score indicates that recall and precision are well-balanced. The overall accuracy achieved is 98.08% for the CNN model. Figure 9 gives the graphical presentation of the precision, recall and f-1 score.

The model’s strong recall, precision, and F-1 scores demonstrate its overall performance across all classes, indicating its ability to effectively recognize and categorize occurrences. The little variations among the classes demonstrate the model’s advantages and possible room for improvement, particularly in achieving the optimal balance between precision and recall for optimal performance. Figure 9 shows the graphical presentation of the performance metrics achieved class-wise for the CNN model.

From Fig. 9, it can be seen that the precision metrics for the five classes vary. For Class 0 and Class 2, the precision ratings indicate that most of the positive projections for these classes are accurate that is, closer to or over 99%. Precision declines in Class 1 and Class 4, demonstrating that the model generates some incorrect prediction errors for these categories of data. The recall values, further change with class. The value of recall in Class 0 and Class 4 is close to 99% which indicates that the model is practically identifying almost all real positive cases in these classes. The lower recall values of Class 1 and Class 2 signifies the model might be lacking some real positive cases, nevertheless. Typically, the F1-score value follows the patterns of recall and precision. Classes 0, 3, and 4 have better F1-Scores because of their symmetrical and high precision and recall values.

Graphical presentation of integrated CNN model accuracy and loss

This section discusses the performance results achieved during the training, testing and validation of the proposed integrated CNN model. The two graphs shown in Fig. 10a,b illustrate the accuracy and loss measurements for the training and validation datasets, thereby highlighting the overall effectiveness of the model covering the 25 epochs. These steps provide some knowledge about the learning and generalizing capability of new data for the model. The performance outcomes attained during the training, testing, and validation of the suggested integrated CNN model are covered in this section. From the Fig. 10a, it can be analyzed that the T.A initially fluctuates and then starts to increase throughout the training span of 25 epochs. This improvement in the value of T.A indicates that the model is learning different feature patterns from the images so that the model can efficiently classify the cervical cell images. The T. A stabilizes until the 25th epoch, when it approaches a nearly perfect accuracy of 99.82%, as a result of these fluctuations decreasing throughout the epochs.

The VA in the graph is also increasing but some fluctuations in its value can be seen as the training is going on, it can be analyzed from this that the model is improving in terms of generalizing to new data. As the training proceeded, the model showed great VA of 99.11%. These high values of VA demonstrates that the training of the model has been completed effectively and the model has learnt the critical patterns from the images. The model has performed greatly on the validation set thus validating the training. From the Fig. 10a the increase in V.A can be seen. Figure 10b displays the graphical presentation of model loss.

The loss, which represents the model’s error, is plotted on the second graph, where the y-axis represents the loss and the x-axis represents the epochs.

Figure 10b clearly shows that the model has started to learn the feature pattern and that the error reduces on the train data as the TL. shows a sharp fall throughout the first few epochs. The variations in the first epochs show the changes in the model in quest of the most suitable parameters. When the training loss consistently drops with time and reaches a low value by the 25th epoch, the model was successful in lowering the number of mistakes on the training set. The other loss curve represented by red color denotes VL. The graph depicts that the value of VL decreases gradually but with more fluctuations than TL. At the start of the training the VL decreases which signifies that the model is gaining knowledge and learning useful information on unseen data. The VL falls to its minimal value showing the best generalizing performance as the training draws to a close at the 25th epoch. At this time the convergence of the training and validation loss curves points to a good balance and non-overfitting of the model. These combined graphs provide the learning process of the model. Based on the always improving and stabilizing accuracy and the loss that is declining, the model is effectively learning from the training data and generalizing properly to the validation data.

Figure 11 displays the confusion matrix recorded during the testing of the proposed integrated CNN model on test dataset. Every row of the confusion matrix shows the real class, every column shows the predicted class. The off-diagonal elements mark misclassifications; the diagonal elements expose the number of essentially discovered occurrences.

From Fig. 11, it can be seen that for Class 0, the model has made 80 correct predictions and one image is misclassified as Class 2, for Class 1, the model predicted 83 correct images and one image is misclassified as Class 0. For Class 2 the model has made correct predictions for 79 images and one image is wrong and classified as Class 4. For Class 3, the 83 images were correctly classified and one image was wrongly classified as for Class 1. The model has correctly classified 79 images for Class 4 whereas no image is misclassified. Out of 408 test images, the model has made correct predictions for 404 images. This demonstrates the efficacy of the model to classify the images precisely. Table 2 describes various performance measurements measured during the evaluation of the model.

From the table, it can be analyzed that Class 0 is showing strong performance with a precision value of 98.99%, a recall value of 98.76% with f-1 score of 98.45%. The model is extremely reliable in recognizing and correctly categorizing cases of this class. Class 1 is having lower precision of 97.79% in comparison with other classes whereas the recall and f-1 value is of 98.82%. Class 2 has 98.75% precision, 98.1% of recall whereas Class 3 has 99.20% and recall of 98.64%. Precision along with recall of 98.76% and 98.86% signifies that the model is effectively classifying the images for all the classes. The model has achieved an overall accuracy of 99.11% depicting the model’s efficacy.

Figure 12 displays the graphical representation of the Integrated CNN model’s performance measures for all five distinct classes. This graph clearly explains how the model is performing differently for every class. In the graph, it can be seen that precision for Class 3 is highest with an optimum value of 99.2% and Class 1 is having slightly lower precision value. This indicated that the model is much more precise in classification for Class 3 labels. The green color line in the graph represents the recall value for all five classes. From this, it can be seen that Class 1 has the highest recall value of 98.82% and Class 2 is having lowest recall value of 98.1%. Class 3 depicts the balanced performance as shown by f-1 value of 98.78%.

The graph shows that although the model performs consistently well across all classes, there are some differences, especially in Class 1 and Class 2 where precision and recall are somewhat lower than in other classes. Class 3’s f-1 value of 98.78% indicates an even performance. Although the model performs well across all classes, the graph reveals some slight variations, particularly in Classes 1 and 2, where precision and recall are marginally lower than in the other classes. The graph shows that although the model performs well in every class, there are some minor differences, especially in Class 1 and Class 2, where precision and recall are a little bit lower than in the other classes.

Comparison of performance of CNN model with integrated CNN model

This section discusses the comparison of both the proposed models in terms of precision, recall, f-1 score and overall performance measures. The comparison has been shown with the help of different graph plots. Figure 13a gives the comparison graph for precision for all five classes. From the graph, it can be seen that The lowest precision value for the integrated CNN model is for Class 1 approximately 98% and the highest value of precision for Class 3 is 99.21%. The CNN model’s highest precision is for Class 3 at 98.8% and lowest for Class 4 at 96.1%. The figure shows that the Integrated CNN model has the highest precision values for all classes compared to the CNN model. This illustrates that the proposed Integrated CNN model is capable of classifying the CC images very precisely. Figure 13b displays the comparison graph for both models regarding Recall. From the figure, it can be noticed that the Integrated CNN model shows the highest recall value for Class 4 at 98.86% and the lowest for Class 2 at 98.1% whereas the CNN model shows the highest recall value for Class 1 at 98.1% and lowest for Class 2 at 96.24%. These results demonstrate that the Proposed Integrated CNN model has outperformed the CNN model in terms of recall also for all five classes. This signifies that the proposed model is capable of identifying and classifying the actual cases effectively.

Figure 14a gives the comparison graph for class-wise f-1 scores for both models. The figure shows that the proposed Integrated CNN model has the highest f-1 score value for Class 4 of 98.9% and lowest for Class 2 of 98.05% whereas the CNN model has shown the highest f-1 score for Class 3 of 98.77% and lowest for Class 2 of 96.89%. From these results also it can be concluded that the proposed Integrated CNN model has shown the greatest f-1 score values than the CNN model. This signifies that the proposed model has a good balance in terms of precision and recall for all five classes. Figure 14b displays the stacked box plot for the combined comparison result of all five classes performance metrics for both models. From this figure the performance measures can be easily noticed that the proposed Integrated CNN framework has outperformed the CNN model.

Table 3 gives the comparison table for both CNN and the Proposed Integrated CNN model. The comparison has been done based on the advantages of both models, their computational cost and overall performance. Figure 15 gives the comparison bar graph for the overall performance of both models. From the figure, it can be easily seen that the Integrated CNN model has performed much better than the CNN model.

Visualization of classification results

In this section, the classification results have been displayed. From where it can be seen that the proposed model has classified the images in a very precise manner. Figure 16 displays the classification results obtained during the testing of the proposed Integrated CNN framework.

Comparison analysis with state of art

This section presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed Integrated CNN Model with specific current research in classifying cervical cells into five distinct categories: Metaplastic, Koilocytes, Dyskeratotic, Parabasal, and Superficial-Intermediate. Table 4 presents a comparison between the proposed study and the current State of Academic Knowledge. The table indicates that the suggested Integrated CNN Model outperformed competing models such as VGG19, ResNet50V2, Ensemble model, and others. It achieved the greatest accuracy of 99.11%, overall precision of 98.69%, recall of 98.63%, and f-1 score of 98.47%. These exceptional results demonstrate the capacity of the suggested framework to categorize cervical cancer cells with more efficiency and accuracy. The closest rival to the suggested Integrated CNN model is VGG19, yet, it has only successfully sorted cervix pictures into two distinct categories. Another formidable rival is the ViT model, which achieves an accuracy of 97.54%, precision of 97.54%, recall of 97.56%, and f-1 score of 97.25%. Thus, by far the best model among all the others is the suggested Integrated CNN model.

Conversely, the Mendeley LBC dataset has shown good performance with the InceptionResNet152V2 model, with an accuracy of 92%. With an accuracy of 97.18%, the ensemble model has likewise performed admirably. When contrasting the latest research, it is clear that the suggested framework has performed better than any other study in terms of accurately categorizing cervical cancer cells. A graphical comparison of the suggested framework with recent investigations is shown in Fig. 17.

From Fig. 17, it can be concluded that the proposed Integrated CNN Model performs extremely well in terms of all performance parameters. The closest well-performing model is VGG19 in terms of accuracy ViT model in terms of Precision, Recall and f-1 score.

Conclusion

The present study is concerned with the development and evaluation of a new integrated CNN model that mainly targets an improvement in cervical cancer cell classification accuracy on the dataset SIPaKMeD. There are 4,049 images of cervical cells inside this dataset that are divided into five different classes; this was the basis used in training and validating the proposed model. The approach incorporated skip connections into a CNN architecture with GANs for data augmentation and pursued the solution of class imbalance. It also improved feature retention across the layers. In comparisons of the proposed integrated CNN model against a standard CNN, large improvements were depicted in most parameters of the performance metrics. For the integrated CNN model, the precision is 98.698%, recall is 98.635%, the F-1 score is 98.478%, and accuracy is 99.11%. This model outperformed the standard CNN model on all parameters. The improvements are due to the skip mechanism, which retains important information throughout the network, and GAN-based augmentation, which significantly enriches the training data to make the model more robust and accurate. The success of the Integrated CNN model presents evidence that it is most likely to be a really very powerful tool for early detection and classification of cervical cancer cells. Conclusively, the findings from this study have implications for improving the performance of deep learning models in medical image classification by integrating of advanced techniques like skip connections and GANs. This can therefore play a key role in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and thus the prognosis of patient outcome by better treatment strategies for cervical cancer. Therefore, the methodology proposed is indeed a quantum leap toward the automation of cervical cancer screening and probably can help reduce the mortality rate by very early diagnosis through accurate identification.

The limitations of this research primarily stem from the relatively small size and lack of diversity in the dataset used, which may affect the model’s generalizability to wider clinical scenarios. Additionally, while the use of GANs helps address class imbalance, it may not fully capture the variability in real-world data. The study also lacks real-world clinical validation, as the model was tested in controlled environments without the inherent challenges of clinical settings. In terms of future scope, expanding the dataset with more diverse and larger collections from multiple sources would enhance the model’s robustness. Testing in real-world clinical settings, improving interpretability through explainable AI techniques, and integrating advanced data augmentation methods like more sophisticated GAN architectures are key areas for further exploration. Additionally, developing hybrid models that combine CNNs with transformers or recurrent neural networks, and conducting longitudinal studies to assess long-term performance, would further enhance the model’s clinical applicability.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study are publicly available at the kaggle repository on the following web link

References

Alyafeai, Z. & Ghouti, L. A fully-automated deep learning pipeline for cervical cancer classification. Expert Syst. Appl. 141, 112951 (2020).

Alquran, H. et al. Cervical cancer classification using combined machine learning and deep learning approach. Comput. Mater. Contin 72(3), 5117–5134 (2022).

Tripathi, A., Arora, A. & Bhan, A. Classification of cervical cancer using Deep Learning Algorithm. In 2021 5th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS) (pp. 1210–1218). IEEE (2021).

Pacal, I. & Kılıcarslan, S. Deep learning-based approaches for robust classification of cervical cancer. Neural Comput. Appl. 35(25), 18813–18828 (2023).

Ghoneim, A., Muhammad, G. & Hossain, M. S. Cervical cancer classification using convolutional neural networks and extreme learning machines. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 102, 643–649 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. CytoBrain: Cervical cancer screening system based on deep learning technology. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 36, 347–360 (2021).

Shandilya, G., Anand, V., Chauhan, R., Pokhariya, H. S. & Gupta, S. Enhanced Cervical Cancer Diagnosis Using Advanced Transfer Learning Techniques. In 2024 2nd World Conference on Communication & Computing (WCONF) (pp. 1–6). IEEE (2024).

Sompawong, N., Mopan, J., Pooprasert, P., Himakhun, W., Suwannarurk, K., Ngamvirojcharoen, J., Vachiramon, T. & Tantibundhit, C. Automated pap smear cervical cancer screening using deep learning. In 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) (pp. 7044–7048). IEEE (2019).

Chandran, V. et al. Diagnosis of cervical cancer based on ensemble deep learning network using colposcopy images. BioMed Res. Int. 2021(1), 5584004 (2021).

Sharma, G., Anand, V., Chauhan, R., Garg, N. & Gupta, S. Deep Learning-Based Blood Cell Disease Classification: A CNN-Enhanced Approach for Accurate Hematological Diagnosis and Treatment. In 2023 2nd International Conference on Futuristic Technologies (INCOFT) (pp. 1–6). IEEE (2023).

Gorantla, R., Singh, R. K., Pandey, R. & Jain, M. Cervical cancer diagnosis using cervixnet-a deep learning approach. In 2019 IEEE 19th international conference on bioinformatics and bioengineering (BIBE) (pp. 397–404). IEEE (2019).

Hemalatha, K. & Vetriselvi, V. (2022). Deep learning based classification of cervical cancer using transfer learning. In 2022 International Conference on Electronic Systems and Intelligent Computing (ICESIC) (pp. 134–139). IEEE.

Khamparia, A., Gupta, D., Rodrigues, J. J. & de Albuquerque, V. H. C. DCAVN: Cervical cancer prediction and classification using deep convolutional and variational autoencoder network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80, 30399–30415 (2021).

Sharma, G., Anand, V. & Gupta, S. Utilizing the inception-ResNetV2 pre-trained model for binary classification of leukemia cells: An advanced approach to hematological diagnostics. In 2023 4th IEEE Global Conference for Advancement in Technology (GCAT) (pp. 1–6). IEEE (2023).

Alsubai, S. et al. Privacy preserved cervical cancer detection using convolutional neural networks applied to pap smear images. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2023(1), 9676206 (2023).

Prasanthi Neerukonda, S. Transfer Learning for Cervical Cancer Image Classification (Doctoral dissertation, California State University, Northridge, 2023).

Göker, H. Detection of cervical cancer from uterine cervix images using transfer learning architectures. Eskişehir Tech. Univ. J. Sci. Technol. A-Appl. Sci. Eng. 25(2), 222–239 (2024).

Arora, M., Dhawan, S. & Singh, K. Exploring deep convolution neural networks with transfer learning for transformation zone type prediction in cervical cancer. In Soft Computing: Theories and Applications: Proceedings of SoCTA 2018 (pp. 1127–1138). Springer Singapore (2020).

Wong, L. et al. Deep learning and transfer learning methods to effectively diagnose cervical cancer from liquid-based cytology pap smear images. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 19(4), 77–93 (2023).

Xu, C. et al. Cervical cell/clumps detection in cytology images using transfer learning. Diagnostics 12(10), 2477 (2022).

Majeed, T., Aalam, S. W., Ahanger, A. B., Masoodi, T. A., Macha, M. A., Bhat, A. A., Bhat, M. R. & Assad, A. Transfer Learning approach for classification of cervical cancer based on histopathological images. In 2023 3rd International conference on Artificial Intelligence and Signal Processing (AISP) (pp. 1–5). IEEE (2023).

Wang, P., Wang, J., Li, Y., Li, L. & Zhang, H. Adaptive pruning of transfer learned deep convolutional neural network for classification of cervical pap smear images. IEEE Access 8, 50674–50683 (2020).

Alzahrani, M., Khan, U. A. & Al-Garni, S. Ensemble and transformer encoder-based models for the cervical cancer classification using pap-smear images. J. Electr. Syst. 20(2), 1637–1646 (2024).

Li, M., Feng, A., Yan, Y., You, S., & Li, C. (2022, August). Deep Convolutional Neural Network Based Cervical Cancer Exfoliated Cell Detection. In International Conference on Image, Vision and Intelligent Systems (pp. 589–598). Springer Nature Singapore.

Fang, M., Fu, M., Liao, B., Lei, X. & Wu, F. X. Deep integrated fusion of local and global features for cervical cell classification. Comput. Biol. Med. 171, 108153 (2024).

Ashfaque, K., BeiJi, Z. & Kui, X. Enhancing cervical cancer diagnosis: Integrated attention-transformer system with weakly supervised learning. Image Vis. Comput. 149, 105193 (2024).

Deo, B. S., Pal, M., Panigrahi, P. K. & Pradhan, A. CerviFormer: A pap smear-based cervical cancer classification method using cross-attention and latent transformer. Int. J. Imag. Syst. Technol. 34(2), e23043 (2024).

Sahoo, P. et al. Enhancing computer-aided cervical cancer detection using a novel fuzzy rank-based fusion. IEEE Access 11, 145281–145294 (2023).

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/prahladmehandiratta/cervical-cancer-largest-dataset-sipakmed/data

Arora, A., Tripathi, A., & Bhan, A. (2021). Classification of cervical cancer detection using machine learning algorithms. In 2021 6th International conference on inventive computation technologies (ICICT) (pp. 827–835). IEEE.

Guo, P., Singh, S., Xue, Z., Long, R., & Antani, S. (2019). Deep learning for assessing image focus for automated cervical cancer screening. In 2019 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical & Health Informatics (BHI) (pp. 1–4). IEEE.

Sun, J., Li, C., Wang, Z. & Wang, Y. A memristive fully connect neural network and application of medical image encryption based on central diffusion algorithm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 20(3), 3778–3788. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2023.3312405 (2024).

Fang, M., Liao, B., Lei, X. & Wu, F.-X. A systematic review on deep learning based methods for cervical cell image analysis. Neurocomputing 610, 128630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128630 (2024).

Sun, J., Yue, Y., Wang, Y. & Wang, Y. Memristor-based operant conditioning neural network with blocking and competition effects. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 20(8), 10209–10218. https://doi.org/10.1109/TII.2024.3393975 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, through Researchers Supporting Project number RSP2024R498.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.S.: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; writing—original draft; software. S.G.: Investigation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. A.A.: Project administration; investigation; methodology; writing—review and editing. S.B.: Validation; investigation; writing—review and editing. A.A.: Writing—review and editing; software; resources; methodology. A.U.R.: Writing—review and editing; methodology; conceptualization. S.H.: Validation; investigation; writing—review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shandilya, G., Gupta, S., Almogren, A. et al. Enhancing advanced cervical cell categorization with cluster-based intelligent systems by a novel integrated CNN approach with skip mechanisms and GAN-based augmentation. Sci Rep 14, 29040 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80260-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80260-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

An automatic cervical cell classification model based on improved DenseNet121

Scientific Reports (2025)