Abstract

Rotala rotundifolia is an amphibious aquatic plant that can live in submerged and emergent forms. It is superior in nitrogen and phosphorus removal and has been used as a traditional medicine in China for over a hundred years. In this study, the bioactive constituents from different tissues of submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia at different growth periods were investigated. The response surface method was used to optimize the flavonoids extraction condition. The amount of flavonoids and triterpenoids from different tissues of R. rotundifolia were much higher than tannins and alkaloids. The highest total flavonoids amount from the leaves of submerged R. rotundifolia was 270.92 ± 13.34 mg/g at day 30 (phyllomorphosis finished), 1.8 times that of the emergent form (150.45 ± 15.11 mg/g). The highest triterpenoids content from the submerged and emergent forms was 242.20 ± 11.51 and 163.09 ± 14.87 mg/g at days 90 and 150 (flowering stage), respectively. The optimal flavonoid extraction conditions were: extraction time 50 min, ultrasonic power 333 W, ethanol concentration 79.3%, and a solid–liquid ratio of 1:60. The LC-MS/MS analysis showed that the extracts from submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia contained 26 and 22 flavonoids, respectively. This study provides phytochemical evidence for the further utilization of R. rotundifolia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rotala rotundifolia is a species belonging to the Lythraceae family. It can live in emergent and submerged forms, which differ in a number of characteristics. Emergent R. rotundifolia is an annual herb and has bright green, broadly oval-shaped leaves. It produces spikes of small, bright pink fuchsia flowers. However, the submerged strain is a perennial without flowers, and its leaves are darker green or reddish, thin, and lanceolate-sword-shaped (Fig. 1). Recent studies have found that this species is superior for nitrogen and phosphorus removal compared with conventional aquatic plants, especially at temperatures as low as 5 ℃1,2. Additionally, they are quite good at adapting to changes in water level because of their amphibious nature. Thus, R. rotundifolia has great potential for purifying eutrophic water and re-establishing aquatic ecosystems. The production of R. rotundifolia is expected to increase significantly in the future as a result of periodically harvesting to remove nutrients from the waters, and control plant overgrowth. Consequently, the exploration of the harvested plants for commercial application would be an emergent issue.

Rotala rotundifolia is commonly used for medicinal purposes. It is known for its detoxication, diuresis, anti-swelling, and antipyretic properties3. Therefore, R. rotundifolia has been used to heal carbuncles, furuncles, rheumatism and arthralgia4. These medicinal properties may be related to the bioactive constituents in the plant. Many Lythraceae have previously been reported to contain flavonoids5,6, triterpenoids7, tannins8, alkaloids9,10, coumarins11, naphthalene derivatives12, etc. Nevertheless, insights into the phytochemical compositions of emergent and submerged R. rotundifolia are yet to be explored.

Herein, the purpose of the paper was to: (1) investigate the total flavonoid, triterpenoid, tannin, and alkaloid content from different parts of submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia; (2) explore the variations in these constituents along with the growth stage; (3) optimize the flavonoid extraction conditions from R. rotundifolia using a response surface methodology (RSM) based on a Box–Behnken design (BBD); and (4) analyze the flavonoids compounds of the extracts from emergent and submerged R. rotundifolia by LC-MS/MS. These results can provide more information about the bioactive composition of emergent and submerged R. rotundifolia as well as appropriate harvest times for the plant to obtain higher concentrations of the bioactive constituents.

Materials and methods

Plants

The R. rotundifolia was retrieved from a remote valley in Wenzhou, and pre-cultured in a greenhouse with all leaves entirely exposed to the air. Sturdy plants with similar height were transplanted into a pot (length×width×height, 40 × 30 × 25 cm). Each pot was planted with 10 strains. A mixture of nutrient soil and sand following a ratio of 1:1 was used as the substrate. The thickness of the sediment was 20 cm. Fifty pots were transplanted into a plastic container and positioned 60 cm below the water level: these pots were defined as the submerged groups. The others (fifty pots) were still maintained in emergent conditions. The plants were sampled at days 30, 60, 90, 150 (flowering), 180, and 270 d for the emergent group, while the submerged plants were sampled at days 30, 60, 90, 180, 270, and 360. Three pots were randomly picked out for analysis each time. The test was carried out from September 2021.

Bioactive constitutes extraction

The stem, leaf and root of the plant were washed with tap water, and then the samples were air- and freeze-dried. Then, the dried sample (moisture content 8.70 ± 0.31%) was ground into a powder using a milling machine and passed through a 100-mesh sieve. The powder (1 g) was placed into a round-bottomed flask, soaked with 50 ml 95% ethanol in an ultrasonic bath, and sonicated for a specific time at 45 ℃. Then the sonicated sample was filtered, and the residue was re-extracted. The sample was extracted three times. The combined extracts were used for the determination of total flavonoid, triterpenoid, tannin, and alkaloid content.

Flavonoid extraction optimization

Based on preliminary one-factor experiments, factors including extraction time (X1), extraction power (X2), ethanol concentration (X3), and solid–liquid ratio (X4) exhibited substantial influence on the flavonoid yield by the ultrasonic-assisted method. Therefore, these factors were adopted as variables in the BBD approach. All variables were fixed at three levels (-1,0,1) with X1 (30, 40, 50 min), X2 (280, 320, 360 W), X3 (65, 75, 85%), and X4 (1:60, 1:50, 1:40). The total flavonoid yield was selected as a dependent response.

LC-MS/MS analysis of flavonoids compounds in the extract

The extract samples obtained under optimal flavonoid extraction conditions were used for LC-MS/MS analysis. The samples were filtered through microfilters at 0.22 μm. LC-MS/MS analyses were performed using a 1290 (UPLC) system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with an electrospray ionization qtof 6550 mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The chromatographic separation was carried out on an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C-18 column (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. The column temperature was set at 40 ℃, and the injection volume was 5 ul. The mobile phases comprised 0.1% formic acid (A), or acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution program was as follows: 0–0.5 min, 5% B; 0.5–10 min, 5-100% B; 10–12 min, 100% B; 12–12.1 min, 100-5% B; 12.1–16 min, 5% B. The samples were injected into the column using an autosampler at 4 ℃. Quality control (QC) samples were used to monitor and evaluate the stability and reliability of the data. The mass spectrometry was operated in negative (ESI-) ion modes. The full-scan spectra were measured with a scan range of 100–1500 m/z. The capillary voltage and pressure of nebulizer were 3200 V and 40 psi, respectively. Sheath gas temperature was 350 ℃, and sheath gas flow was 12 L/min. Compound identification was performed by comparing of accuracy m/z value (< 10 ppm) and the MS/MS spectra with an in-house database (Shanghai Applied Protein Technology) established with available authentic standards13.

Analytic methods

The total flavonoid content was determined by the aluminium trichloride method using rutin as a reference compound14. The amount of total triterpenoids was measured using the vanillin–perchloric acid assay method15. The total tannin content was measured with the Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent method, as described by Guo et al.16, with gallic acid as the standard solution. Whereas the total alkaloid amount was determined spectrophotometrically according to the method described by Guo et al.16.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS software (ver. 26.0). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to test the significance of the results, and differences at p < 0.05 level were considered statistically significant. The experimental data were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

Results and discussion

Total flavonoid, triterpenoid, tannin, and alkaloid content from submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia at different growth stages

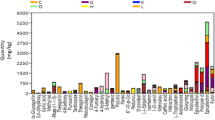

Total flavonoids

The ANOVA analysis showed that the content of flavonoids from leaves of both submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia was significantly higher than those from the roots and stems (p < 0.05, Fig. 2a, b). This was consistent with studies on tomato by Silv-Beltran et al. (2015), ginkgo seedlings by Xu et al.17, and cannabis by Jin et al.18. This may be described to the high concentration of primary metabolites in the leaves due to photosynthesis. The amount of total flavonoids from submerged R. rotundifolia leaves was highest (270.92 ± 13.34 mg/g) at day 30, 1.8 times that from emergent R. rotundifolia, which reached its peak at 150.45 ± 15.11 mg/g during days 30–90. This declined by 42.14% from days 30 to 60, but did not change significantly among days 60 to 180 (155.69 ± 11.07-156.74 ± 6.53 mg/g, p > 0.05). The total flavonoid amount from the stems changed slightly during the test, and the values were 23.71 ± 1.60-29.64 ± 1.05 mg/g, whereas the total flavonoid content from the roots did not change significantly (p > 0.05, 12.53 ± 0.67–14.28 ± 3.51 mg/g). The total flavonoid content from submerged R. rotundifolia leaves was much higher than that from medicine plants Perilla frutescens (72.54 mg/g)19 and Eugenia uniflora (177.2 mg/g)20.

Flavonoids are secondary metabolites in plants. They play a crucial role in mediating the responses of plants to external environmental stresses, such as cold, salinity and drought21,22. The research of Dias et al.23 found that flavonoids were capable to scavenge free radicals and acted as an antioxidant. Flavonoid biosynthesis is usually upregulated in response to a wide range of abiotic stresses24. In the initial stage, R. rotundifolia suffered from waterlogging threat, resulting in an increase in flavonoids. After 2 weeks of waterlogging, an obvious change in leaf shape was observed. The plant developed thin and slender leaves which were different from those that were exposed to air. The leaf morphology transition was completed around day 30. This might indicate that the plant was adapted to the underwater conditions. This may be the reason for the rapid decrease in flavonoid content from days 30 to 60 due to the “disappearance” of the waterlogging threat.

For the emergent form, total flavonoid amount from the leaves was significantly higher at days 30 to 90 (p < 0.05), ranging from 123.92 ± 4.63 to 150.45 ± 15.11 mg/g. This quickly fell afterwards, reaching 25.10 ± 6.72 mg/g at day 150 (flowering), possibly due to the reduced precursor content for flavonoid synthesis at the pre-flowering stage. The research of Jia et al.25 suggested that this is due to abundant sugars transport from the leaf to floral meristems to provide energy for flower development. Total flavonoid amounts from both the roots and stems did not change significantly, ranging between 5.55 ± 0.56 and 16.72 ± 1.55 mg/g and 5.55 ± 0.75 and 29.99 ± 3.54 mg/g, respectively.

Total triterpenoids

The triterpenoid content in R. rotundifolia was also higher in the leaves (Fig. 2c, d). The amount of total triterpenoids from the leaves of submerged R. rotundifolia showed an increase in the initial stage, reaching 227.76 ± 20.33 and 242.20 ± 11.51 mg/g at days 60 and 90, respectively, which is much higher than from Inonotus Obliquus (16.96 mg/g)26 and Lactuca indica leaves (33.96 mg/g)27. At day 270, this dropped to 122.2 ± 6.00 mg/g, the lowest value in the test. Variations in the total triterpenoids from the stems and roots were similar to the leaves, and higher total triterpenoid amounts were obtained at days 60 and 90. The corresponding amounts were 126.64 ± 16.15 and 137.76 ± 15.18 mg/g and 143.09 ± 14.51 and 156.87 ± 9.48 mg/g, respectively. These results demonstrated that the submerged R. rotundifolia contained a higher content of triterpenoids, and an appropriate harvest time would be from days 60 to 90.

Total triterpenoid content extracted from the leaves, stems and roots of emergent R. rotundifolia did not change significantly during days 30–90 (p > 0.05). Afterwards, they increased progressively and reached a peak at day 150 (flowering stage). The highest amount of total triterpenoids from the leaves, stems, and roots was 163.09 ± 14.87, 138.64 ± 14.64, and 117.31 ± 2.30 mg/g, respectively. These results illustrated that triterpenoids in emergent R. rotundifolia were higher during the flowering stage. This may be due to the increase in the associated metabolic enzyme activity. The research of Guo et al.28 for terpene biosynthesis in lavender reported that all six HDR genes involved in the methylerythritol pathway (MEP) were observed to be significantly upregulated during flower development, reflecting more efficient terpenoid biosynthesis.

Total tannins

Compared with flavonoids and triterpenoids, the total tannin content extracted from R. rotundifolia was much lower (Fig. 3a, b). Higher tannin amounts from submerged R. rotundifolia were obtained on days 60 and 90 from the leaves and stems, respectively (leaves: 16.82 ± 0.05 and 17.04 ± 0.06 mg/g, stems: 15.99 ± 1.41 and 16.26 ± 0.26 mg/g), whereas the total tannin content from the roots was relatively low, less than 4.10 mg/g. For the emergent form, the total tannin amount from the leaves was significantly higher than from the stems and roots (p > 0.05). It was observed that the total tannin content was relatively higher on days 30 (19.32 ± 0.05 mg/g), 90 (20.34 ± 0.46 mg/g), and 180 (19.26 ± 1.30 mg/g). The total tannin amount from the stems was higher in the initial period, whereas from the roots it steadily increased from day 30, reaching a peak at days 150 (12.44 ± 0.94 mg/g) and 180 (12.21 ± 1.84 mg/g).

Total alkaloids

Total alkaloid amount from the leaves of submerged R. rotundifolia was highest at day 30 (23.52 ± 1.77 mg/g), then the amount declined substantially (Fig. 3c). At day 60, it decreased to 10.40 ± 0.68 mg/g. The amounts of total alkaloids from the stems (3.35 ± 0.46–5.09 ± 0.06 mg/g) and roots (2.29 ± 0.35–3.98 ± 0.05 mg/g) were much lower. The amounts of total alkaloids from the leaves, stems, and roots of the emergent form showed a downward trend (Fig. 3d). The highest amount was obtained on day 30. The corresponding values from the leaves, stems, and roots were 16.18 ± 0.45, 6.73 ± 0.13, and 4.45 ± 0.05 mg/g, respectively.

Optimization of the flavonoids extraction conditions

Mathematical model and statistical analysis

Since there were much more flavonoids in R. rotundifolia than other constituents, more research was done on the procedure of extracting. The extraction conditions for flavonoid extraction from R. rotundifolia by the ultrasonic-assisted method were optimized using RSM-BBD. A multiple regression analysis was used to fit the experimental data and derive a second-order polynomial quadratic equation:

According to the coefficients of the term, the influence order of the variables was as follows: X1 > X3 > X4 > X2. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) is presented in Table 1. The model F-value (449.41) and smaller p value (p < 0.0001) indicated that the model was significant and that the terms in the model had a significant effect on the response. The “lack of fit F-value” of 3.81 implied the “lack of fit” was not significant relative to the pure error, and the model fitted well. The p values of X1, X2, X3, and X4 were less than 0.0001, thereby showing that they were significant. Additionally, the model’s determination R2, adjusted R2 and predicted R2 values were 0.9959, 0.9919, and 0.9787, respectively. This demonstrated that theoretical values predicted by the proposed model were in reasonable agreement with the experimental results. The adequate precision of 63.2215 (greater than 4) indicated an adequate signal and that the model could be used to navigate the design space. A relatively low coefficient of variation value (C.V.=1.45%) showed that the experiment’s accuracy and dependability were adequate25. Figure 4 shows the Box–Cox plot for the power transformation, with the blue and green lines representing the current and best lambda values, respectively. The current lambda (1) lies within the confidence interval and is close to the optimal design value (0.99); therefore, no transformation is recommended.

Response surface analysis

Figure 5a–f displays three-dimensional (3D) response surface plots between the independent variables. The response surface plots were generated by varying two variables within the experimental range under investigation and holding the other variables at a central level (0 level). It was observed that the total flavonoid content was low (18.43 mg/g) at the extraction time of 40 min and ultrasonic power 360 W. This gradually increased with the increase in extraction time and decrease in ultrasonic power, until reaching a maximum (29.56 mg/g) at around 45 min and 320 W, and then subsequently decreasing. It has been established that ultrasonic-assisted extraction can enhance the mass transfer and accelerate solvent penetration by disrupting the cell walls of plant tissues29. Furthermore, it can raise the temperature and promote the solubility of flavonoids in the solvent30. However, an excessive temperature increase may cause a decrease in cavitation, thus resulting in the oxidation and degradation of some flavonoids31,32. An extended extraction time provides enough time for the solubilization of flavonoids, but it may bring about decomposition of some flavonoids due to acoustic cavitation33. The response of the total flavonoid content to the extraction time was significantly affected by the ultrasonic power, as shown in Fig. 5a.

Three-dimensional (3D) response surface plots: effects of extraction time (X1) and extraction power (X2) (a), extraction time (X1) and ethanol concentration (X3) (b), extraction time (X1) and solid–liquid ratio (X4) (c), extraction power (X2) and ethanol concentration (X3) (d), extraction power (X2) and solid–liquid ratio (X4) (e), and ethanol concentration (X3) and solid–liquid ratio (X4) (f).

Figure 5b illustrates the interaction between extraction time (X1) and ethanol concentration (X3). With an increase in extraction time, the total flavonoid content gradually increased first and then decreased slightly. Similarly, the total flavonoid content increased with the increase in ethanol concentration, and then it decreased after an ethanol concentration of 78%. This may be ascribed to the polarization and solubility of flavonoids in the ethanol–water mixture. For example, the glycosides with high polarity are easily soluble in water. Whereas flavones are very soluble in ethanol. Furthermore, an increase in ethanol concentration may promote the breakdown of the cell membrane, enhancing the permeability of solvent into the solid matrix34. However, it was not significant that the increase in ethanol concentration affected the total flavonoid amount at a certain extraction time. This result is in agreement with the results of the ANOVA, highlighting that the mutual interaction between the ethanol concentration and extraction time is not significant.

The total flavonoid content was highest at an extraction time of 50 min and a solid–liquid ratio of 1:60 (Fig. 5c). This progressively declined with a decrease in extraction time and an increase in the solid-liquid ratio. It is worth noting that the total flavonoid content response to the solid–liquid ratio was not obvious at extraction times less than 35 min. A higher solvent volume was conducive to flavonoids extraction, as a larger concentration gradient of the solvent enhanced the mass transfer efficiency35, but this depended on the extraction time. Figure 5d displays that the total flavonoid content can be obtained at an ultrasound power of 280–340 W and an ethanol concentration of 70–80%. When the solid–liquid ratio was between 1:50 and 1:60, a lower ultrasound power (280–340 W) and ethanol concentration (73–85%) resulted in a higher total flavonoid amount (Fig. 5e, f).

Optimization of the extraction parameters and validation of the model

According to the model, the optimal operation conditions for optimal total flavonoid yield were extraction time 50 min, ultrasonic power 333.18 W, ethanol concentration 79.26%, and a solid–liquid ratio of 1:60. To facilitate the experimental operation, the conditions were adjusted to: extraction time 50 min, ultrasonic power 333 W, ethanol concentration 79.3%, and a solid–liquid ratio of 1:60. The predicated total flavonoid amount was 32.90 ± 0.36 mg/g. The actual total flavonoid amount obtained was 32.33 ± 0.65 mg/g, and the relative error was only 1.73%. Thus, the model was suitable and reliable.

Flavonoids compounds in the extracts from submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia by LC-MS/MS

The extracts from submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia were analyzed using LC-MS/MS, and the total ion chromatograms are presented in Fig. 6. The flavonoid compounds are displayed in Table 2. There are 26 and 22 flavonoids in the extract from submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia, separately. Four compounds, including medicarpin, (-)-epicatechin gallate, hispidulin 4’-glucoside, and methoxyluteolin were not identified in the extract from emergent R. rotundifolia. The top 5 compounds in abundance in the extract from submergent R. rotundifolia were quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, 5,8-dihydroxyflavanone, isoquercitrin, kaempferol 3,7-diglucoside, and quercetin 3-O-(6’’-acetyl-glucoside), whereas in the extract from emergent R. rotundifolia were: quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, epigallocatechin, kaempferol 3,7-diglucoside, myricetin-3-galactoside, and dihydroquercetin, respectively. This demonstrated that flavonoids species and content in the plant in different habitat were significantly different.

Conclusion

The amounts of flavonoids and triterpenoids from the leaves of both the submerged and emergent forms were significantly higher than from the roots and stems. The highest total flavonoid amount from the leaves of the submerged form was 270.92 ± 13.34 mg/g at day 30, 1.8 times that of emergent R. rotundifolia, which reached its peak at 150.45 ± 15.11 mg/g at day 90. The highest total triterpenoid content from submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia was 242.20 ± 11.51 and 163.09 ± 14.87 mg/g at days 90 and 150, respectively. Thus, the leaves of submerged R. rotundifolia had the highest content of flavonoids and triterpenoids, and the best harvest times were days 30 and 60–90 after submergence, respectively. The optimal flavonoids extraction conditions were extraction time 50 min, ultrasonic power 333 W, ethanol concentration 79.3%, and solid–liquid ratio 1:60. The LC-MS/MS analysis revealed that the extracts from submerged and emergent R. rotundifolia contained 26 and 22 flavonoids, respectively.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Yang, Y., Zhang, X., Xiao, J., Chu, S. & Huang, Z. Nutrient removal by Rotala rotundifolia: A superior candidate for ecosystem remediation at low temperature. RSC Adv. 10, 29139 (2020).

Chu, S., Zhang, X., Xiao, J. & Chen, R. Dynamic nutrient removal potential of a novel submerged macrophyte Rotala rotundifolia, and its growth and physiological response to reduced light available. J. Environ. Manage. 293, 112965 (2021).

Karatas, M., Aasim, M. & Çiftçioglu, M. Adventitious shoot regeneration of roundleaf toothcup-Rotala rotundifolia [(Buch-Ham. Ex Roxb) Koehne]. J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 24, 838–842 (2014).

Tan, Q., Cai, X., Feng, T. & Luo, X. Megastigmance-type compounds from Rotala rotundifolia. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 7, 187–189 (2009).

Diab, Y., Atalla, K. & Elbanna, K. Antimicrobial screening of some Egyptian plants and active flavones from Lagerstroemia indica leaves. Drug Discov Ther. 6, 212–217 (2012).

Al-Snafi, A. The chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Ammannia baccifera: A review. Int. J. Pharm. 5, 28–32 (2015).

Wu, S. & Tian, L. A new flavone glucoside together with known ellagitannins and flavones with anti-diabetic and anti-obesity activities from the flowers of pomegranate (Punica granatum). Nat. Prod. Res. 33, 252–257 (2019).

Upadhyay, H. C., Thakur, J. P., Saikia, D. & Srivastava, S. K. Anti-tubercular agents from Ammannia baccifera (Linn). Med. Chem. Res. 22, 16–21 (2013).

Lee, I. et al. Biphenyl and biphenyl ether quinolizidine N-oxide alkaloids from Lagerstroemia indica L. Planta Med. 77, 2037–2041 (2011).

Li, Q. et al. New cytotoxic compounds from flowers of Lawsonia inermis L. Fitoterapia 94, 148–154 (2014).

Zhang, L. J., Yeh, S. F., Yu, Y. T., Kuo, L. M. Y. & Kuo, Y. H. Antioxidative flavonol glucuronides and anti-HBsAg flavonol from Rotala rotundifolia. J. Traditional Complement. Med. 1, 57–63 (2011).

Hsouna, A. B., Trigui, M., Culioli, G., Blache, Y. & Jaoua, S. Antioxidant constituents from Lawsonia inermis leaves: Isolation, structure elucidation and antioxidative capacity. Food Chem. 125, 193–200 (2011).

Gu, Z., Li, L., Tang, S., Liu, C. & Fu, X. Metabolomics reveals that crossbred dairy buffaloes are more thermotolerant than holstein cows under chronic heat stress. J. Agric. Food Chem. 66, 12889–12897 (2018).

Abdel-Hameed, E. S. S., Nagaty, M. A., Salman, M. S. & Bazaid, S. A. Phytochemicals, nutritionals and antioxidant properties of two prickly pear cactus cultivars (Opuntia ficus indica Mill.) Growing in Taif, KSA. Food Chem. 160, 31–38 (2014).

Song, L. J. et al. Optimized extraction of total triterpenoids from Jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.) And comprehensive analysis of triterpenic acids in different cultivars. Plants 9, 412 (2020).

Guo, L., Qiang, T., Ma, Y., Ren, L. & Dai, T. Purification and characterization of hydrolysable tannis extracted from Coriaria nepalensis bark using macroporous resin and their application in gallic acid production. Ind. Crop Prod. 162, 113302 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Light intensity affects the growth and flavonol biosynthesis of Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L). New. For. 45, 765–776 (2014).

Jin, D., Dai, K., Xie, Z. & Chen, J. Secondary metabolites profiled in Cannabis inflorescences, leaves, stem barks, and roots for medicinal purposes. Sci. Rep. 10, 3309 (2020).

Shang, X. et al. Chemical compositions, extraction optimizations, and in vitro bioactivities of flavonoids from Perilla leaves (Perillae folium) by microwave-assisted natural deep eutectic solvents. Antioxidants 12, 104 (2023).

Ramos, R. T. M., Bezerra, I. C. F., Ferreira, M. R. A. & Soares, L. A. L. Spectrophotometric quantification of flavonoids in herbal material, crude extract, and fractions from leaves of Eugenia uniflora Linn. Pharmacognosy Res. 9, 253–260 (2017).

Jan, R. et al. Enhanced flavonoid accumulation reduces combined salt and heat stress through regulation of transcriptional and hormonal mechanisms. Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 796956 (2021).

Shomali, A. et al. Diverse physiological roles of flavonoids in plant environmental stress responses and tolerance. Plants 11, 3158 (2022).

Dias, M. C., Pinto, D. & Silva, A. M. Plant flavonoids: Chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules 26, 5377 (2021).

Li, B. et al. The flavonoid biosynthesis regulator PFG3 confers drought stress tolerance in plants by promoting flavonoid accumulation. Environ. Exp. Bot. 196, 104792 (2022).

Jia, S. et al. Mineral and metabolic profiles in tea leaves and flowers during flower development. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 106, 316–326 (2016).

Wang, Y., Guo, L., Liu, C., Zhang, Y. & Li, S. Total triterpenoid extraction from Inonotus Obliquus using ionic liquids and separation of potential lactate dehydrogenase inhibitors via ultrafiltration high-speed countercurrent chromatography. Molecules 26, 2467 (2021).

Hao, J. et al. Optimization of extraction process and dynamic changes in triterpenoids of Lactuca indica from different medicinal parts and growth periods. Molecules 28, 3345 (2023).

Guo, D., Kang, K., Wang, P., Li, M. & Huang, X. Transcriptome profiling of spike provides expression features of genes related to terpene biosynthesis in lavender. Sci. Rep. 10, 6933 (2020).

Zhen, S. et al. Ultrasound-assisted natural deep eutectic solvent extraction and bioactivities of flavonoids in Ampelopsis grossedentata leaves. Foods 11, 668 (2022).

Dranca, F. & Oroian, M. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of total monomeric anthocyanin (TMA) and total phenolic content (TPC) from eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) peel. Ultrason. Sonochem. 3, 637–646 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Subcritical ethanol extraction of flavonoids from Moringa oleifera leaf and evaluation of antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 218, 152–158 (2017).

Qin, L., Yu, J., Zhu, J., Kong, B. & Chen, Q. Ultrasonic-assisted extraction of polyphenol from the seeds of Allium Senescens L. and its antioxidative role in Harbin dry sausage. Meat Sci. 172, 108351 (2021).

Sulaiman, I. S. C. et al. Effects of temperature, time and solvent ratio on the extraction of phenolic compounds and the anti-radical activity of Clinacanthus nutans Lindau leaves by response surface methodology. Chem. Cent. J. 11, 54 (2017).

Azahar, N. F., Gani, S. S. A. & Mohd Mokhtar, N. F. Optimization of phenolics and flavonoids extraction conditions of Curcuma Zedoaria leaves using response surface methodology. Chem. Cent. J. 11, 96 (2017).

Santos-Zea, L., Gutierrez-Uribe, J. A. & Benedito, J. Effect of solvent composition on ultrasound-generated intensity and its influence on the ultrasonically assisted extraction of bioactives from Agave Bagasse (Agave Salmiana). Food Eng. Rev. 13, 713–725 (2021).

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 42007146 and the Science and Technology Program of Wenzhou China grant number S2023006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chu S.Y. and Xiao J.B. conceived the idea for this research and proposed the research design. Chu S.Y. wrote the manuscript and contributed to fund acquisition. Shi Z.J. and Wu Y.X. carried out the experiment, analyzed and interpreted the research data. Xiao J.B. supervised the research and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical statement

Rotala rotundifolia used in this study was planted by ourselves. This species is a common plant in China and is not listed as an endangered species. Therefore, it is not involved in ‘IUCN Endangered Species Research Policy Statement’ and ‘Convention on Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora’ do not apply to this species. As a result, this article does not need to involve this statement.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chu, S., Shi, Z., Xiao, J. et al. Bioactive constituents of amphibious Rotala rotundifolia at different growth stages and response surface optimization for flavonoid extraction. Sci Rep 14, 29055 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80300-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80300-w