Abstract

Data on hyperuricemia-related changes in coronary atherosclerosis are limited, especially in sex difference. This study evaluated the association between hyperuricemia and coronary artery calcification (CAC) progression in asymptomatic Korean men and women. We analysed the data of 12,316 asymptomatic adults (51.7 ± 8.5 years; 84.2% men) with a mean follow-up of 3.3 years. Participants were divided into two groups: those with and without hyperuricemia (serum uric acid levels > 7.0 mg/dL for men and > 6.0 mg/dL for women). CAC progression was defined as a difference of ≥ 2.5 between the square roots of the baseline and follow-up coronary artery calcium score (CACS) (Δ√transformed CACS). The incidence of CAC progression was higher in men with hyperuricemia than in those without the condition (37.9% vs. 32.3%, P < 0.001); however, no significant difference in the incidence of CAC progression was observed in women with and without hyperuricemia (20.2% vs. 15.8%, P = 0.243). After adjusting for age, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, obesity, current smoking status, serum creatinine, baseline CACS, and inter-scan periods, hyperuricemia was associated with increased risk of CAC progression in men (odds ratio [OR]: 1.20, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.06 − 1.36, P = 0.004); however, hyperuricemia was not significantly associated with the risk of CAC progression in women (OR: 0.73, 95% CI: 0.36 − 1.49, P = 0.385). In conclusion, hyperuricemia is more closely associated with CAC progression in men than in women among asymptomatic Korean adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High serum uric acid (SUA) levels are closely related to diverse metabolic abnormalities, such as obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidaemia, which are well-established cardiovascular (CV) risk factors1. Previous studies have suggested the potential effect of uric acid on atherosclerosis through vascular smooth cell proliferation and endothelial dysfunction2,3. Although numerous studies have investigated the relationship between SUA and coronary heart disease, the results have been conflicting4,5,6,7,8 Particularly, there is a paucity of data with large sample sizes on the association between hyperuricemia and changes in coronary atherosclerosis. The coronary artery calcium score (CACS) is widely used for CV risk stratification in asymptomatic adult populations because of its prognostic value across age, sex, and ethnicity9. Recent data have shown that early detection of the presence and progression of coronary artery calcification (CAC) is important in primary prevention10,11. However, little is known about the risk of CAC progression related to hyperuricemia in men and women despite sex differences in the association between SUA levels and diverse clinical diseases12,13. This study aims to evaluate the association between hyperuricemia and the risk of CAC progression in an asymptomatic Korean adult population of men and women.

Methods

Study design

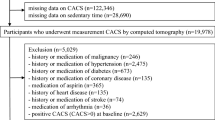

This observational multicentre cohort study enrolled 12,316 self-referred asymptomatic adults from the Korea Initiative on Coronary Artery Calcification (KOICA) Registry. In brief, all participants with available data regarding SUA levels underwent at least two CAC scans from December 2003 to August 2017. A flowchart of the present study is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Self-reported medical questionnaires were used to collect medical history. Height and weight were measured with participants wearing light clothing and no shoes. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m2). Blood pressure (BP) was measured using an automatic manometer on the right arm after resting for at least 5 min. All blood tests, including total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), uric acid, glucose, and creatinine levels, were performed after at least 8 h of fasting. Computed tomography (CT) was performed to measure CACS using 16-slice multidetector scanners (Siemens 16-slice Sensation, Siemens, Forchheim, Germany; Philips Brilliance 40-channel multidetector CT, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH, USA; Philips Brilliance 256 iCT, Philips Healthcare; GE 64-slice Lightspeed, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA). All scans were performed using a standard electrocardiogram-triggered scan protocol. At each participating center, CACS was assessed by experienced CV radiologists, and the results were reported in electronic health records.

Hyperuricemia was defined as SUA levels > 7.0 mg/dL in men and > 6.0 mg/dL in women14. Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg, a previous medical history of hypertension, or the use of antihypertensive medication15. Diabetes was defined as a fasting glucose level of ≥ 126 mg/dL, a previous diagnosis of diabetes, or the use of anti-diabetic medication16. Dyslipidemia was defined as a serum level of total cholesterol of ≥ 240 mg/dL, triglyceride of ≥ 150 mg/dL, HDL-C of ≤ 40 mg/dL, LDL-C of ≥ 130 mg/dL, or taking anti-dyslipidemic medication17. Obesity was defined as a BMI of ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 using the BMI cut-offs for Koreans18. Current smoking was defined as current smoking or smoking 1 month before the study17. The CACS was measured using a scoring system previously described by Agatston et al.19. CAC progression was defined using the SQRT method as a difference of ≥ 2.5 between the square root (√) of the baseline and follow-up CACS (Δ√transformed CACS)10,20, considering the proportion of CACS of 0 in our participants at baseline and the strong prognostic value of CAC progression defined with the SQRT method10. Annualised Δ√transformed CACS was defined as Δ√transformed CACS divided by the inter-scan period. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Severance Cardiovascular Hospital approved the study protocol (IRB No: 4-2014-0309).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or the median (interquartile range), and categorical variables are presented as absolute values and percentages. After checking the distribution status of the independent variables, we compared the participants’ characteristics using an independent t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test for continuous variables, as appropriate, and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the relationship between clinical variables and risk of CAC progression. Subsequently, multiple logistic regression models were used to examine the association between hyperuricemia and the risk of CAC progression; the forced entry method was used to enter the independent variables into the multiple regression models. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19 (SPSS; Chicago, Illinois, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 in all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

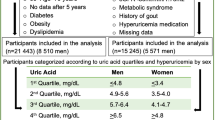

The baseline characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was 51.7 ± 8.5 years, and 10,373 (84.2%) of them were men. The mean level of SUA was 5.8 ± 1.3 mg/dL, and the overall prevalence of hyperuricemia was 16.5%. Systolic and diastolic BP, BMI, TG, LDL-C, creatinine, glucose, and SUA levels, and the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, obesity, and hyperuricemia were significantly higher in men than in women. However, men were younger and had significantly lower total cholesterol and HDL-C levels than did women.

Baseline and the changes of CAC according to hyperuricemia

The baseline categorical CACS is shown in Fig. 1. The baseline categorical CACS was significantly different between men and women; a proportion of CACS of 0 was significantly lower in men compared with women (53.3% vs. 71.6%; P < 0.001). In men, the baseline categorical CACS did not differ significantly according to hyperuricemia; however, significant difference in the categorical CACS related to the presence of hyperuricemia was observed in women. During a mean follow-up of 3.3 years, the incidence of CAC progression was significantly higher in men than in women (33.3% vs. 16.0%, P < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The Δ√transformed CACS, annual changes in Δ√transformed CACS, and the incidence of CAC progression were significantly higher in overall participants with hyperuricemia than in those without hyperuricemia. These findings were consistently observed in men; however, no significant differences in the Δ√transformed CACS, annual changes in Δ√transformed CACS, and the incidence of CAC progression according to hyperuricemia status were observed in women (Table 2).

Clinical variables and the risk of CAC progression

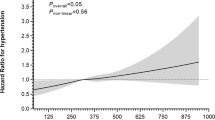

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity, and current smoking status were significantly and positively associated with the risk of CAC progression in men. Age, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity were similarly associated with the risk of CAC progression in women. Hyperuricemia was significantly associated with an increased risk of CAC progression in men; however, this association was not observed in women (Table 3).

Association of hyperuricemia with the risk of CAC progression

In the multiple logistic regression models with consecutive adjustments for clinical factors, including age, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity, current smoking, serum creatinine, baseline CACS, and inter-scan periods, hyperuricemia was significantly associated with the risk of CAC progression in men. However, no significant association between hyperuricemia and the risk of CAC progression was observed in women (Table 4). The results of multiple linear regression models to evaluate the association of SUA levels (per-1 mg/dL increase) with Δ√transformed CACS are presented in Supplementary Table 1; the SUA levels were significantly associated with Δ√transformed CACS in men, but not in women, after adjusting for age, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity, current smoking, serum creatinine, baseline CACS, and inter-scan periods.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the longitudinal cohort study with the largest sample size to identify sex differences in the association between hyperuricemia and CAC progression among asymptomatic adults. In the present study, the incidence rates of CAC progression in men and women were 33.3% and 16.0%, respectively. The incidence of CAC progression was significantly higher in men with hyperuricemia than in those without hyperuricemia. However, no significant difference in the incidence of CAC progression according to hyperuricemia was observed in women. After adjusting for confounding factors, hyperuricemia was independently associated with the risk of CAC progression in men but not in women. The strength of this study is that the risk of CAC progression was assessed in an asymptomatic adult population without heavy CAC at baseline. According to the data from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study11, repeated CT scans for CAC evaluation after 5 years could provide individual risk readjustment attributable to the increased risk in subjects with baseline CACS < 400; in contrast, despite a higher CV risk in subjects with baseline CACS > 400, additional CACS evaluation did not have prognostic value in baseline condition of CACS > 400. In the present study, the proportion of baseline CACS > 400 in overall participants was only 2.6%; the prevalence of baseline CACS > 400 in men and women was 2.8% and 1.4%, respectively.

Several studies have evaluated the association between SUA levels and coronary atherosclerosis; however, the results have been inconsistent. The Novara Atherosclerosis Study reported that SUA levels were not significantly associated with the prevalence and extent of coronary artery disease (CAD), which was defined as at least one coronary lesion with > 50% stenosis in 1901 consecutive patients who underwent invasive coronary angiography21. In contrast, a recent observational cohort study consisting of 6431 asymptomatic Korean adults with no previous history of CAD who voluntarily underwent coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) as part of a general health examination reported that the risk for any plaque and non-calcified plaque increased with higher SUA levels22. Regarding sex differences in the association between SUA and CAD, Barbieri et al.23 observed that high SUA levels are associated with three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease with > 50% stenosis only in women, despite higher SUA levels in men than in women from the same registry. These inconsistent results might be related to the presence of cardiogenic symptoms and the different ethnicities of the participants24.

Budoff et al.10 reported that CAC progression added incremental value in predicting all-cause mortality over baseline CACS, interscan periods, demographics, and CV risk factors in 4,609 asymptomatic adults during a mean inter-scan period of 3.1 years. According to the results from the Heinz-Nixdorf Recall registry11, which consists of 3,281 asymptomatic adults with a mean inter-scan period of 5.1 years, CAC progression was significantly associated with prognosis in patients with non-heavy CAC at baseline. In addition, the Progression of Atherosclerotic Plaque Determined by Computed Tomographic Angiography Imaging (PARADIGM) registry showed that baseline coronary plaque burden is the most important factor, when compared with clinical and laboratory measures, for predicting the risk of rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis using the machine learning framework25. These findings clearly demonstrate the significance of early detection of the presence and progression of CAC in primary prevention of asymptomatic adults. Furthermore, the COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multicentre (CONFIRM) study found that additional prognostic benefit was not conferred by CCTA when compared to the CACS with traditional risk factors in the population of asymptomatic adults26. The present study identified the different associations of hyperuricemia with the risk of CAC progression according to sex among asymptomatic Korean adults with extremely low proportion of heavy CAC at baseline.

Previous studies examined the association between SUA levels and CAC in asymptomatic adult populations. A single-center and cross-sectional study reported that SUA was independently related to the severity of CAC, particularly in males (older and non-obese) with no history of diabetes, hypertension, smoking, or renal dysfunction among 4188 Korean adults without prior CAD or urate-deposition disease27. In a longitudinal observational study, Bjornstad et al.28 reported that SUA independently predicted the development of CAC progression as well as albuminuria, rapid decline in renal function, and diabetic retinopathy in 652 patients with type 1 diabetes. Similarly, the Rancho Bernardo Study showed that SUA is an ethnicity-specific marker of CAC severity and CAC progression among 368 postmenopausal White and Filipino women29. Recent meta-analysis results also revealed that hyperuricemia is independently associated with an increased risk of CAC development and progression in 11 studies involving 11,108 asymptomatic adults30. However, there is a paucity of data on the risk of CAC progression related to hyperuricemia with a focus on sex differences. In the present study, the prevalence of hyperuricemia was higher in men than in women (18.6% vs. 5.1%; P < 0.001). Notably, the risk of CAC progression was significantly different according to hyperuricemia status only in men. Although hyperuricemia could contribute to the atherosclerotic process via endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation31,32,33, the sex difference in CAC progression in our participants could be influenced by the function of estrogen promoting uric acid excretion before menopause in females34. However, the exact mechanisms of sex difference in the effect of SUA on arteriosclerosis remain unclear, and further research is necessary.

The current study had some limitations. First, this study was performed in a relatively healthy population who voluntarily participated in a health check-up, which may have resulted in a selection bias. Second, this was an observational study that may have been influenced by unidentified confounders. Third, we could not control for medications for hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, or hyperuricemia because of the observational design of our study. Fourth, despite the possible effect of estrogen status on atherosclerosis35, menstrual phase or menopausal status at the time of evaluating CAC were not considered because of the limited data in this cohort registry. However, (a) this study identified a higher proportion of CACS of 0 in women compared with men, and (b) a large proportion (77.2%) of female participants was over 45 years of age. Finally, this study included only the Korean population, which may have limited the generalisability of our results. Nevertheless, this study is unique in that we assessed the risk of CAC progression by focusing on sex difference in an asymptomatic Korean population using a large sample size.

In summary, both the prevalence of hyperuricemia and the incidence of CAC progression were significantly higher in men than in women. Hyperuricemia is positively and significantly associated with the risk of CAC progression in only men among asymptomatic Korean adults. Further studies are required to identify the effect of SUA on coronary atherosclerosis, particularly those focusing on sex differences.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Chu, N. F. et al. Relationship between hyperuricemia and other cardiovascular disease risk factors among adult males in Taiwan. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16, 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007654507054 (2000).

Johnson, R. J. et al. Is there a pathogenetic role for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal disease? Hypertension 41, 1183–1190. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000069700.62727.C5 (2003).

Rabelink, T. J. et al. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase: host defense enzyme of the endothelium? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 26 https://doi.org/10.1161/01.ATV.0000196554.85799.77 (2006). 267 – 271.

Coutinho. Tde, A. et al. Associations of serum uric acid with markers of inflammation, metabolic syndrome, and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Am. J. Hypertens. 20 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.06.015 (2007). 83 – 89.

Rodrigues, T. C. et al. Serum uric acid predicts progression of subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in individuals without renal disease. Diabetes Care. 33, 2471–2473. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc10-1007 (2010).

Neogi, T. et al. Serum urate is not associated with coronary artery calcification: The NHLBI Family Heart Study. J. Rheumatol. 38, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100639 (2011).

Larsen, T. R. et al. The association between uric acid levels and different clinical manifestations of coronary artery disease. Coron. Artery Dis. 29, 194–203. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCA.0000000000000593 (2018).

Lim, D. H. et al. Serum uric acid level and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic individuals: an observational cohort study. Atherosclerosis 288 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.07.017 (2019) 112 – 117.

Detrano, R. et al. Coronary calcium as a predictor of coronary events in four racial or ethnic groups. N Engl. J. Med. 358, 1336–1345. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa072100 (2008).

Budoff, M. J. et al. Progression of coronary artery calcium predicts all-cause mortality. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 3, 1229–1236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.08.018 (2010).

Lehmann, N. et al. Value of progression of coronary artery calcification for risk prediction of Coronary and Cardiovascular events: result of the HNR Study (Heinz Nixdorf Recall). Circulation 137, 665–679. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027034 (2018).

Yu, X. L. et al. Gender difference on the relationship between hyperuricemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among Chinese: an observational study. Med. (Baltimore). 96, e8164. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000008164 (2017).

Chen, J. H. et al. Sex difference in the associations among hyperuricemia with new-onset chronic kidney disease in a large Taiwanese population follow-up study. Nutrients 14, 3832. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14183832 (2022).

Gois, P. H. F. et al. Pharmacotherapy for hyperuricaemia in hypertensive patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 9, CD008652. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008652.pub4 (2020).

Lawes, C. M. et al. Blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific Region. J. Hypertens. 21, 707–716. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200304000-00013 (2003).

American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes. Diabetes. Care. 47(Suppl 1), S20–42. (2024). https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S002

Shin, S. et al. Impact of serum calcium and phosphate on coronary atherosclerosis detected by cardiac computed tomography. Eur. Heart J. 33, 2873–2881. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs152 (2012).

Kim, K. K. et al. Evaluation and Treatment of Obesity and its comorbidities: 2022 update of clinical practice guidelines for obesity by the Korean Society for the Study of Obesity. J. Obes. Metab. Syndr. 32, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.7570/jomes23016 (2023).

Agatston, A. S. et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 15, 827–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t (1990).

Hokanson, J. E. et al. Evaluating changes in coronary artery calcium: an analytical approach that accounts for interscan variability. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 182, 1327–1332. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.182.5.1821327 (2004).

De. Luca, G. et al. Uric acid does not affect the prevalence and extent of coronary artery disease. Results from a prospective study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 22, 426–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2010.08.005 (2012).

Lim, D. H. et al. Serum uric acid level and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic individuals: an observational cohort study. Atherosclerosis 288, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.07.017 (2019).

Barbieri, L. et al. Impact of sex on uric acid levels and its relationship with the extent of coronary artery disease: a single-centre study. Atherosclerosis 241, 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.03.030 (2015).

Nasir, K. et al. Ethnic differences in the prognostic value of coronary artery calcification for all-cause mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 50, 953–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.066 (2007).

Han, D. et al. Machine learning framework to identify individuals at risk of rapid progression of coronary atherosclerosis: from the PARADIGM Registry. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e013958. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.013958 (2020).

Cho, I. et al. Prognostic value of coronary computed tomographic angiography findings in asymptomatic individuals: A 6-year follow-up from the prospective multicentre international CONFIRM study. Eur. Heart J. 39, 934–941. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx774 (2018).

Kim, H. et al. Asymptomatic hyperuricemia is independently associated with coronary artery calcification in the absence of overt coronary artery disease: a single-center cross-sectional study. Med. (Baltimore). 96, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006565 (2017).

Bjornstad, P. et al. Serum uric acid predicts vascular complications in adults with type 1 diabetes: The coronary artery calcification in type 1 diabetes study. Acta Diabetol. 51, 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-014-0611-1 (2014).

Calvo., R. Y. et al. Relation of serum uric acid to severity and progression of coronary artery calcium in postmenopausal White and Filipino women (from the Rancho Bernardo study). Am. J. Cardiol. 113, 1153–1158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.022 (2014).

Liang, L. et al. The association between hyperuricemia and coronary artery calcification development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Cardiol. 42, 1079–1086. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23266 (2019).

Papežíková., I. et al. Uric acid modulates vascular endothelial function through the down regulation of nitric oxide production. Free Radic Res. 47, 82–88. https://doi.org/10.3109/10715762.2012.747677 (2013).

Sautin, Y. Y. et al. Uric acid: the oxidant-antioxidant paradox. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 27, 608–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/15257770802138558 (2008).

White, J. et al. Plasma urate concentration and risk of coronary heart disease: a mendelian randomisation analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 4, 327–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00386-1 (2016).

Antón., F. M. et al. Sex differences in uric acid metabolism in adults: Evidence for a lack of influence of estradiol-17 beta (E2) on the renal handling of urate. Metabolism 35, 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/0026-0495(86)90152-6 (1986).

Tomiyama, H. et al. Influences of age and gender on results of noninvasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity measurement: A survey of 12517 subjects. Atherosclerosis 166, 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00332-5 (2003).

Funding

This work was supported by Institute of Information & communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No.2022000972, Development of flexible mobile healthcare software platform using 5G MEC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KBW and HJC conceived of and interpreted the data. KBW, SYC, EJC, SHP, JS, HOJ, and HJC contributed to the data acquisition. KBW and HJC performed the statistical analyses. KBW drafted the manuscript. HJC revised the manuscript critically. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have given final approval and agreed to be held accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring its integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of the present study was approved by the institutional review board of each institution, and written informed consent for procedures was obtained from each participant (IRB No: 4-2014-0309).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Won, KB., Choi, SY., Chun, E.J. et al. Sex difference in the risk of coronary artery calcification progression related to hyperuricemia among asymptomatic 12,316 Korean adults. Sci Rep 14, 28710 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80324-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80324-2

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Data-driven analysis of the relationship between the HbA1c/HDL-C ratio and coronary artery calcification: a cross-sectional study

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on serum uric acid levels: a meta-analysis

European Surgery (2025)

-

Association between serum uric acid levels and arterial stiffness in patients with psoriasis

Archives of Dermatological Research (2025)