Abstract

This study aimed to calculate Italy’s first national maternal mortality ratio (MMR) through an innovative record-linkage approach within the enhanced Italian Obstetric Surveillance System (ItOSS). A record-linkage retrospective cohort study was conducted nationwide, encompassing all women aged 11–59 years with one or more hospitalizations related to pregnancy or pregnancy outcomes from 2011 to 2019. Maternal deaths were identified by integrating data from the Death Registry and national and regional Hospital Discharge Databases supported by the integration of findings from confidential enquiries conducted through active surveillance. Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR), direct MMR (DMMR), and causes of maternal death are the study main outcomes. The MMR was found to be 8.4 per 100,000 live births (95% CI 7.5–9.3), significantly higher than the 3.9 per 100,000 (95% CI 3.3–4.5) calculated solely from the Death Registry, with a notable declining trend over the study period. Causes of death have been classified according to the 10th International Classification of Diseases. Within 42 days from pregnancy outcome, leading causes were obstetric haemorrhage, sepsis, and cardiovascular diseases. Late maternal deaths were primarily attributed to suicide, malignancies, and cardiovascular diseases. This integrated methodology provides a comprehensive understanding of maternal mortality trends and causes in Italy, offering valuable insights for countries utilizing or planning enhanced surveillance systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Maternal mortality is acknowledged as a critical indicator of maternal healthcare quality. Accurate measurement and continuous monitoring prove essential for assessing the effectiveness of healthcare services for pregnant women, from conception to the 42 days following pregnancy outcome1. Nonetheless, collecting data on maternal mortality remains a challenge due to variations in sources and methodologies2. Enhanced Obstetric Surveillance Systems (EOSS) operating in eight European countries, part of the International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems (INOSS)3, revealed that Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) estimates obtained solely from vital statistics analysis did not comprehensively capture the extent of this phenomenon. Moreover, such estimates do not provide accurate insights into the causes of maternal deaths4. It has been demonstrated that record-linkage procedures between Death Registries (DR) and Hospital Discharge Database (HDD) improve the estimation of MMR by identifying those fatalities for which death records alone do not provide information on pregnancy status4. However, linkage is not always possible, as strict privacy rules prevent researchers from accessing nominal data, and not all countries are equipped with interconnected databases.

The Italian National Health Service guarantees universal healthcare access. The national government sets the standard national benefits package and allocates funds to regional health systems. Administration, planning, and service delivery at the local level are overseen by the 19 Italian Regions and 2 Autonomous Provinces. However, there are significant regional disparities, particularly disadvantaging the southern regions of the country in terms of healthcare provision and health outcomes5.

Italy has shown a strong commitment to preventing avoidable maternal deaths by instituting an EOSS designed to detect and monitor maternal mortality6,7 coordinating several research initiatives on obstetric near misses8,9,10,11,12, developing evidence based clinical practice guidelines13, and offering training opportunities to healthcare professionals engaged in the childbirth care continuum14. This bundle of activities is centrally coordinated by the Italian Obstetric Surveillance System (ItOSS) at the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (the Italian National Institute of Health) adopting a dual methodology, aimed at identifying and critically reviewing maternal fatalities. This approach involves retrospective record-linkage procedures between regional DR and regional HDD6, complemented by a prospective incident reporting and Confidential Enquiries system7.

Officially recognized since 2017 through a Decree of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers15 as a nationally significant surveillance system, ItOSS represents a research enterprise of clinical investigators, supported by an operational unit in each Italian Region and an extensive network of focal points in each maternity unit across the country.

Since the initial computation of MMR in 2008, ItOSS estimated that six out of ten maternal deaths were not accounted for in national statistics16. In 2023, ItOSS achieved a significant milestone, by producing the first national estimate of MMR through an innovative record-linkage approach, the methodology of which is described in this paper.

This study aims to provide insights into the computation of the first national MMR in Italy and the description of the causes of maternal death within the EOSS coordinated by ItOSS.

Methods

Data sources and methodologies adopted

The absence of nominal data and the lack of interconnected databases at the national level had previously hindered the calculation of a national estimate of MMR. Since 2020, the Italian National Institute of Health has initiated a collaboration with the Agenzia nazionale per i servizi sanitari regionali (Agenas), enabling access to national HDD through the Programma Nationale Esiti17. This source gathers non-nominal national data concerning integrated clinical and administrative information along with vital status and date of death of each woman residing in Italy. Vital status and date of death are centrally inserted in the data source by the Ministry of Health through linkage with the tax registry, which serves as the most reliable source for verifying residents’ vital status. To identify maternal deaths, national HDD were linked to the national DR using a non-nominal linking key composed of the woman’s date of birth, date of death, region of residence, and citizenship. From the national DR, the underlying cause of death was extracted. This is coded using the IRIS software18, which takes into account the entire sequence of causes of death listed on the certificate. The identified deaths were compared with those found through nominal regional record-linkage and added to the estimate if previously missing. Except for Fig. 1, all data presented refer to the integrated method combining nominal regional record-linkage and national record-linkage as described above. The integration of information from confidential enquiries in cases overlapping with active surveillance helped clarify some previously unknown causes. However, this was not feasible for late deaths which are not captured by active surveillance, or for regions and periods when the system was not yet operational. The flow chart (Fig. 1) summarizes the three integrated information sources (HDD, DR and active surveillance) and outlines the variables obtained from each source.

All women aged 11 to 59 years who died between 2011 and 2019 within 365 days from the end of any pregnancy outcome (miscarriage, induced abortion, ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, or live birth), residing or domiciled in Italy at the time of death, and discharged from any public or private hospital were included in the study.

Classification of deaths

In accordance with the WHO Application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium: ICD-MM18, deaths occurring within one year of the end of pregnancy regardless of their cause, were categorized as pregnancy-associated deaths. Selected cases were categorized as maternal death (occurring during pregnancy or within 42 days following any pregnancy outcome) and late maternal deaths (from 43 to 365 days after any pregnancy outcome).

Deaths were classified into two groups based on their causes: direct deaths, resulting from obstetric complications of pregnancy, interventions, omissions, incorrect treatments, or a chain of events stemming from any of the above; and indirect deaths, resulting from pre-existing diseases or diseases developed during pregnancy not due to direct obstetric causes but aggravated by the physiological effects of pregnancy. Compared to previous Italian data, aortic dissection was categorized among cardiovascular diseases rather than spontaneous hemoperitoneum. Additionally, all suicides were classified as direct deaths, and only female neoplasms and those related to the skin were included among malignancies, while others were classified as accidental deaths. In a secondary analysis, maternal deaths were classified using a thematic approach, irrespective of the direct or indirect nature of the cause19.

Two methods were used to attribute the cause of death: one based on the ICD- MM20 and another, being more clinically specific, which was derived from integrating national and/or regional HDDs (Supplementary Table S1).

Each maternal death was attributed to the Italian Region where it occurred. To validate the data of the national record-linkage approach, results were compared with previous findings obtained from a nominal regional record-linkage in 10 Italian Regions where regional sources are available6.

To ensure confidentiality, data cells with fewer than three cases were labelled as " < 3."

Main outcome measures and statistical analysis

MMR and DMMR were calculated from 2011 to 2019 at the national level, as well as for different geographic areas (North, Central, South, and Islands) and Regions. These ratios were determined by calculating the number of deaths and direct maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, along with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI), assuming a binomial distribution Poisson approximation. To assess changes in MMR, a chi-square test was computed to analyze national trend by calendar years. Additionally, a rolling 3-year average ratio and its 95% CI were calculated for each geographical area. Bivariate analysis was performed to determine the association with potential risk factors (maternal age and citizenship), estimated by calculating the crude risk ratio (RR) and their 95%CI, using a comparison with a denominator obtained from the national HDDs. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (version 9.4).

Results

MMR computation

From 2011 to 2019, Italy experienced 4,373,438 live births and 368 maternal deaths, resulting in a national integrated MMR of 8.41 (95%CI 7.58–9.32) per 100,000 live births. Notably, the MMR exhibited regional variation, ranging from 3.6 in Tuscany to 13.1 in Sicily (Table 1). The national DMMR was 5.05 (95%CI 4.41–5.77) per 100,000, representing 60.1% of maternal deaths. Most of the southern Regions exhibited a higher DMMR, exceeding 65% (Table 1).

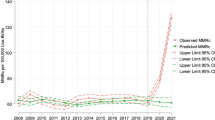

Figure 2 shows the proportion of MMR computed by each method. The MMR computed solely from the DR (3.84 per 100,000, 95%CI 3.28–4.47) was found to be lower than the ratio derived from the integration of both national and regional linkage procedures. This underestimation, quantified at 54%, remained consistent over the years examined. The MMR derived solely from national record linkage (6.97 per 100,000) missed some cases due to date compilation errors. The MMR derived solely from regional record-linkage (6.08 per 100,000) lacked data from eight Italian Regions and failed to account for deaths of non-residents women within the Region. The integrated MMR in the Regions lacking regional record-linkage estimates aligns with the national MMR (Fig. 2).

The national MMR showed a decline from 10.98 (95%CI 8.38–14.13) in 2011 to 8.62 (95%CI 6.04–11.93) per 100,000 in 2019 (data not shown by single year), indicating a statistically significant downward trend (p-value for trend < 0.001). Geographical analysis revealed a convergence of three-year average MMRs over time, with similar values observed in the triennium 2017–2019 for the North, Centre and South and Islands (Fig. 3).

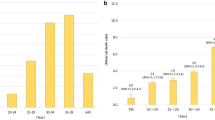

Maternal mortality risk factors

The risk of maternal mortality increased with the woman’s age. Compared to younger women, those aged 35–40 had a RR of 1.76 (95%CI 1.41–2.20), while those over 40 years old had a RR of 3.93 (95%CI 2.90–5.33). Women of non-Italian citizenship also showed a higher relative risk (RR = 1.57, 95%CI 1.24–1.99), particularly those from Asia (RR = 1.90, 95%CI 1.24–2.91) and Africa (RR = 1.76, 95%CI 1.21–2.57) (Table 2).

Maternal mortality causes

Among the total 368 identified maternal deaths within 42 days from pregnancy outcome, obstetric haemorrhage (MMR = 1.74) emerged as the leading cause (Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1S). When combined with sepsis (MMR = 1.12), cardiac pathology (MMR = 0.91), thromboembolism (MMR = 0.64), and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (MMR = 0.62), they accounted for 60% of the detected fatalities. In 46 out of 368 cases (12.5%), the cause of death could not be determined due to the lack of specific coding (e.g. cardiac arrest, cause unspecified). An obstetric code identifying the cause of maternal death was available in 96 out of 368 cases (25.8%), while for all other fatalities the cause of death was reported using non-obstetric ICD-10 codes.

Among the 308 maternal deaths occurring between 43 and 365 from pregnancy outcome, suicide (29.9%) was the most frequent cause, followed by malignancies (28.6%) and cardiovascular diseases (11.7%), accounting together for 70% of late maternal deaths (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1S). Breast cancer and cardiomyopathy were the leading causes of maternal deaths attributed to neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. The proportion of unknown causes of late maternal deaths was equal to 14.6%.

After reclassifying suicides as direct deaths, the DMMR increased from the previous estimate of 4.6 per 100,0005 to 5.1 in the current study (Table 1).

Supplementary Table 1S cross-referenced the causes of maternal death attributed through the ICD-MM classification and the integrated method adopted by ItOSS. The latter allowed for the quantification of specific causes of mortality within the two broader categories outlined by the ICD-10 groups: i.e. pregnancies with abortive outcomes, and other obstetric complications.

Discussion

The innovative integration of retrospective record-linkage procedures enabled a comprehensive and improved estimation of the Italian first national MMR for the years 2011–2019, establishing it at 8.4 per 100,000 live births. The analysis of the temporal trend revealed a statistically significant reduction and a convergence, in the last triennium, of the historically observed differences by geographical areas. The DMMR remained above 50% of maternal deaths, and women aged ≥ 35 years and those of non-Italian citizenship exhibited a higher risk of maternal death. Obstetric haemorrhage persisted as the primary cause of fatalities within 42 days of pregnancy outcome. Suicides, malignancies, and cardiovascular diseases were, in order of frequency, the top three causes responsible for 70.2% of Italian late maternal deaths.

The study’s strengths lie in the computation of the first national MMR and in the robustness of the innovative record-linkage approach compared to previous estimates. This integrated system combined the strengths of both national and regional record-linkage procedures while also benefiting from information gathered through confidential enquiries into maternal deaths within 42 days, supported by ItOSS active surveillance. It allowed for the calculation of MMR in regions without access to administrative data, facilitated access to inter-regional mobility data, and ensured the inclusion of non-resident women. Additionally, the system benefitted from regional procedures by utilizing a stronger linkage key based on nominal data. The integrated approach also offered the opportunity to address limitations related to data errors in national record-linkage, errors in nominal data, and untimely data in regional record-linkage. Study limitations involve the lack of local comparison data in all regions and the reclassification of certain causes of death (e.g. suicide and aortic dissection) compared to previous ItOSS analyses. Moreover, despite the innovative integrated record-linkage approach, the percentage of maternal deaths with unknown cause ranged from 12 to 15% due to the intrinsic limitation resulting from the absence or incorrect coding of the cause of death in HDRs and DRs which affected similarly (15% of unidentified cause) also the previous ItOSS data6. The achievement of nationwide active surveillance in 2023 has enabled more accurate identification of causes of maternal deaths within 42 days, with a reduction in unknown causes expected as confidential enquiry data is integrated. Additionally, ItOSS plans to extend these enquiries to include late maternal deaths, a practice currently carried out only by EOSS in France and the UK, which will further reduce the proportion of unknown causes.

A population-based study conducted by INOSS provides a valuable comparison among eight European countries equipped with EOSS4. The Italian subnational MMR estimated between 2013 and 2015 was 8.7 per 100,000 live births, falling between France (8.0/100,000) and the UK (9.6/100,000)4.

While the MMR trend detected between 2006 and 2012 remained consistently stable6, the detected significant decrease, from 11.0 in 2011 to 8.4 in 2019 per 100,000 live births, reflected the extensive efforts of ItOSS over the past decade. These efforts involved the implementation of the bundle of ItOSS activities described in the introduction of the paper8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Additionally, collaborative efforts among national public health agencies, scientific societies, universities, healthcare institutions, and healthcare professionals have played a pivotal role in reducing preventable maternal deaths. Notably, there has been a significant decline in the specific MMR for obstetric haemorrhage, before and after the ItOSS bundle implementation, dropping from 2.49 in 2007–2013 to 0.77 in 2014–2018 across six Italian regions, encompassing 49% of births21,22. Moreover, the detected specific MMRs for haemorrhage and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy have both decreased compared to those recorded by ItOSS between 2006 and 2012, dropping from 1.92 to 1.74 for haemorrhage and from 1.06 to 0.62 for hypertensive disorders. It should be noted that the current national data encompassed more southern regions than the previous ItOSS estimate6, which may have mitigated the observed reduction due to higher MMRs in the South compared to the rest of the country. The significant decrease in regional disparities, leading to a convergence of maternal mortality rates (MMRs) between 2017 and 2019, likely reflects the impact of strategies aimed at improving maternal care quality. This outcome holds significant public health implications, particularly in southern regions historically associated with poor maternal outcomes6. In these areas, worst outcomes extend beyond maternal mortality, including higher rates of caesarean sections, maternal morbidity, and perinatal mortality—likely driven by greater challenges in accessing adequate care23. These poorer outcomes may contribute to the persistently high DMMR in the South compared to the Central-Northern regions, though the reduction in MMR provides a promising sign of progress.

In Italy, like in other European countries equipped with EOSS, advanced maternal age and foreign citizenship increase the maternal mortality risk3. Asian and African women, mirroring findings in the UK24, exhibited significantly higher MMRs than Italian women.

In line with other high-income countries3, suicide, malignancies and cardiovascular diseases remained among the top causes of late maternal deaths. Compared to the causes of maternal death described by ItOSS for the period 2006–20126, we observed a consistent increase in maternal deaths due to suicides (29.9% vs. 10.0%), in line with recent findings in the Netherlands where the proportion of suicides rose to 28% in 2006–202025. The proportion of maternal deaths attributable to cardiovascular disease is also increasing (11.7% vs. 8.5%), following trends observed across all high-income countries3,26. The noticeable reduction in deaths from malignancies (28.6% vs. 38.8%), was likely due to coding changes that excluded brain and blood cancers from maternal death classifications. A recent retrospective Italian study focusing on cohorts of women aged 15–49 diagnosed with cancer during pregnancy, identified a rate of 1.24 pregnancy-associated cancers (PAC) per 1,000 pregnancies. In line with the literature and with the ItOSS data, breast cancer resulted the most prevalent site27.

Overcoming the dichotomy between direct and indirect causes through the adoption of a thematic approach, provided a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the relative impact of each cause of maternal death. Even in a country like Italy, where obstetric transition is at stage 4b marked by low maternal mortality stage (MMR < 20)28, direct causes of death still outweigh indirect causes. However, it is evident that attention must be directed not only to obstetric causes but also to suicides, neoplasm, and cardiovascular diseases.

From a methodological perspective, the innovative approach adopted in this study may offer valuable insight for other countries currently employing or planning to implement EOSS. The inclusion of the individual’s living status in the HDRs allowed national record-linkage procedures with the DR, resulting in the first-ever national estimate of the MMR. The subsequent integration of both national and regional record-linkage procedures enabled the examination of previous hospitalizations in cases of unclear causes of death and allowed effectively addressing the limitations of both methods and capitalising on their respective strengths. Moreover, this approach has proven effective in reducing underestimation compared to the previous figures relying solely on regional record-linkage procedures, providing greater accuracy in detailing the causes of maternal deaths. This improvement was further supported by the integration of findings from confidential enquiries conducted through active surveillance.

Conclusion

The research to refine methods for accurately tracking trends in maternal mortality and attributing causes of death demands continuous innovation and validation. This study’s integrated method helped estimate Italy’s national MMR at 8.4 per 100,000 live births, aligning with European counterparts. Italian data highlight maternal suicide and cardiovascular diseases as priority areas for action. Effectively addressing conditions unrelated to obstetric complications requires a cultural shift in clinical practices, emphasizing health promotion, prevention, early diagnosis, and a multidisciplinary approach in healthcare provision. The ItOSS experience underscores the proactive role of EOSS beyond MMR trend description, advocating for comprehensive initiatives to ensure better health outcomes for pregnant women.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy regulations. The analyzed phenomenon is rare, and case identification is easily possible even when anonymized. The National Institute of Health has the authority to analyze the data under a ministerial decree that permits its use and dissemination only in aggregated form.

Change history

28 May 2025

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the author name Edoardo Corsi Decenti was incorrectly indexed. The original Article has been corrected.

References

Shennan, A. H., Green, M. & Ridout, A. E. Accurate surveillance of maternal deaths is an international priority. BMJ 379, o2691 (2022).

Joseph, K. S. et al. Maternal mortality in the United States: Are the high and rising rates due to changes in obstetrical factors, maternal medical conditions, or maternal mortality surveillance?. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 230(440), e1-440.e13 (2024).

Knight, M. et al. The International Network of Obstetric Survey Systems (INOSS): Benefits of multi-country studies of severe and uncommon maternal morbidities. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 93(2), 127–131 (2014).

Diguisto, C. et al. Maternal mortality in eight European countries with enhanced surveillance systems: Descriptive population based study. BMJ 379, e070621 (2022).

National Institute of Statistics ISTAT. Popolazione e Famiglie. https://www.istat.it/it/popolazione-e-famiglie?dati.

Donati, S. et al. Maternal mortality in Italy: Results and perspectives of record-linkage analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 97(11), 1317–1324 (2018).

Donati, S., Maraschini, A., Dell’Oro, S., Lega, I. & D’Aloja, P. The way to move beyond the numbers: The lesson learnt from the Italian Obstetric Surveillance System. Ann. Inst. Super Sanita. 55(4), 363–370 (2019).

Maraschini, A. et al. Women undergoing peripartum hysterectomy due to obstetric hemorrhage: A prospective population-based study. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 99(2), 274–282 (2020).

Ornaghi, S., Maraschini, A., Donati, S. & Regional Obstetric Surveillance System Working Group. Characteristics and outcomes of pregnant women with placenta accreta spectrum in Italy: A prospective population-based cohort study. PLoS ONE 16(6), e0252654 (2021).

Donati, S., Fano, V. & Maraschini, A., Regional Obstetric Surveillance System Working Group. Uterine rupture: Results from a prospective population-based study in Italy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 264, 70–75 (2021).

Maraschini, A. et al. Eclampsia in Italy: A prospective population-based study (2017–2020). Pregnancy Hypertens. 30, 204–209 (2022).

Ornaghi, S. et al. Maternal Sepsis in Italy: A prospective, population-based cohort and nested case-control study. Microorganisms 11(1), 105 (2022).

Donati, S. et al. Emorragia Post Partum: Come Prevenirla, Come Curarla. Sistema Nazionale Linee Guida 2016 (Ed. Zadig) Linea Guida n. 26, Roma

D’Aloja, P. et al. Acceptance of e-learning programs for maternity healthcare professionals implemented by the Italian Obstetric Surveillance System (ItOSS). J. Contin. Educ. Health Prof. 40(4), 289–292 (2020).

DPCM 3 marzo 2017 Identificazione dei sistemi di sorveglianza e dei registri di mortalità, di tumori e di altre patologie, in attuazione del Decreto legge n. 179 del 2012” - GU Serie Generale n.109 del 12–5–2017.

Donati, S., Senatore, S. & Ronconi, A. Regional maternal mortality working group. Maternal Mortality in Italy: A record linkage study. BJOG 118(7), 872–879 (2011).

PNE Programma Nazionale Esiti. https://pne.agenas.it/home (2024).

Iris software www.iris-institute.org

van den Akker, T. et al. Netherlands Audit Committee Maternal Mortality Morbidity; UK Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths. Maternal mortality: Direct or indirect has become irrelevant. Lancet Glob. Health 5(12), e1181–e1182 (2017).

World Health Organization. The WHO Application of ICD-10 to Deaths During Pregnancy, Childbirth and the Puerperium: ICD-MM (World Health Organization) 1–67 (2013).

Donati, S. et al. Uptake and adherence to national guidelines on postpartum haemorrhage in Italy: The MOVIE before-after Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(7), 5297 (2023).

Donati, S. et al. The Italian Obstetric Surveillance System: Implementation of a bundle of population-based initiatives to reduce haemorrhagic maternal deaths. PLoS ONE 16(4), e0250373 (2021).

Certificato di Certificato di assistenza al parto (CeDAP). Analisi dell’evento nascita - Anno 2019. https://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_3076_allegato.pdf

Knight, M. et al. MBRRACE-UK Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care Core Report - Lessons Learned to Inform Maternity Care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2019–21 (National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2023).

Lommerse, K. M. et al. The contribution of suicide to maternal mortality: A nationwide population-based cohort study. BJOG. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17784 (2024).

CDC. Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-mortality/php/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance/index.html

Pierannunzio, D. et al. Cancer and pregnancy: Estimates in Italy from record-linkage procedures between cancer registries and the hospital discharge database. Cancers (Basel) 15(17), 4305 (2023).

Souza, J. P. et al. A global analysis of the determinants of maternal health and transitions in maternal mortality. Lancet Glob. Health. 12(2), e306–e316 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the invaluable work of the Regional ItOSS Working Group (please see full list of the Working group in the Supplemental Material), and the Italian Ministry of Health (IMOH) and National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) for sharing the national data files. We also acknowledge the help of Silvia Andreozzi in the graphic editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

AM made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, conducted the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript. DM made contributions to the design of the study, conducted the statistical analyses. IL, PD, and ECD contributed to the interpretation of the results, and critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. GB took responsibility for the national HHD data and the accuracy of the data analysis. GM took responsibility for the national DR and the accuracy of the data analysis. SD made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, contributed to draft the manuscript, to the interpretation of the results, and critically reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content. The ItOSS Regional Working Group provided regional record-linkage data and supported the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the National Ethics Committee of the Italian National Health Institute (Prot. PRE-C318/15, Rome 12/05/2015). The study was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was not obtained from patients or their families as the study was based on the analysis of institutional forms, and patient records and information were anonymized prior to analysis. All data analysis and processing were conducted in accordance with applicable guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maraschini, A., Mandolini, D., Lega, I. et al. Maternal mortality in Italy estimated by the Italian Obstetric Surveillance System. Sci Rep 14, 31640 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80431-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80431-0