Abstract

Roof breaking is the root cause of rock burst and mine earthquake. However, the classical “thin plate theory” and “thick plate theory” cannot fully reveal the mechanical mechanism of the influence of roof thickness-span ratio on the fracture mode. In this paper, based on the cohesive element technology, the mechanical behavior of cohesive element failure was studied according to the maximum nominal stress criterion and BK fracture criterion, and the fracture mechanical behavior of roofs with different thicknesses fixed on four sides under uniform load was numerically simulated. The fracture pattern and the maximum principal stress evolution laws of roofs with different thicknesses were obtained. The results show that there are three fracture modes of the plates with different thickness: pure tensile fracture mode at the bottom surface, mixed fracture mode around the “X” shape crack, and pure shear fracture mode along the long edge boundary. The crack morphology of thin plate is the transverse “O−X” type, and the crack morphology of thick plate is the “O−❋” type. With the increase of thickness, the tensile-shear mixed failure mode gradually changes from the tensile dominant to the shear dominant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rupture of overlying strata often leads to dynamic disasters (such as rock burst and mine earthquake) and a series of ecological environmental problems (such as ground settlement and groundwater pollution)1, which seriously threatens the safety production of coal mines and environmental protection. Many scholars have conducted extensive research on the movement and fracture of hard rock strata caused by mining through theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and in-site investigation2,3. These studies indicate that the instantaneous fracture of thick hard roof will cause dynamic disasters such as roadway instability and rock burst, and the movement and rupture of overlying hard rock layers are related to the mechanical property, thickness, and position of the roof. In addition, the advancement of the coal seam working face directly influences the stress distribution of the basic roof and changes the thickness-span ratio of the goaf roof. Therefore, it is very important to understand the movement law and failure mode of thick hard roof strata to control the behavior of rock mass. The influence of roof thickness is a factor that cannot be ignored.

Numerous researchers have extensively investigated the fracture behavior of overburden structure with different thickness by using the “plate theory” as a theoretical framework. Based on the traditional “thin plate theory”, Pu et al.4 theoretically studied the evolution process of roof fracture, and discussed the “X−O” fracture morphology of roof through three-dimensional numerical simulation. However, there is a large error when the “thin plate theory” is applied to medium-thick plates in practical engineering. Therefore, considering the influence of transverse shear deformation, the “medium plate theory” is proposed as an alternative approach. Based on the “Reissner plate theory”, Li et al.5 derived the theoretical formula for the first breaking span of thick and hard roof. On this basis, based on the “Vlasov plate theory”, the theoretical formula of the periodic breaking span of thick and hard roof was deduced with the boundary condition of simply supported on four sides. They used these two formulas to verify the breaking span of thick and hard roof in Tashan Coal Mine, and proved that its accuracy is higher than the traditional “beam theory”. Furthermore, Gao et al.6 introduced the Trigon logic into UDEC, and successfully captured the characteristics of crack generation and propagation in the process of progressive collapse of rock strata. They used a damage index to quantify regions of both compressive shear and tensile failure within the modelled longwall. This model reproduced multiple features of progressive collapse, indicating that compressive shear failure is the main failure mechanism in the collapsed strata above the goaf, rather than tensile failure. The immediate roof act like a beam and can collapse in beam bending when the vertical stress is dominant or in beam shear fracture when the horizontal stress is dominant. Ning et al.7 used the microseismic monitoring technology to study the mining induced cracking and migration of double-layer hard thick roof. The structural characteristics affected by the roof rupture are identified, which is helpful to explain the strong formation behavior. Zuo et al.8 analyzed the fracture laws of the roof using the “thick plate theory” and pointed out that the shear stress is an important factor in the whole layer cutting of the roof. Combined with the laboratory experiment9, it was found that the “X” crack is the main fracture morphology. The thin plate is mainly characterized by long edge “O−X” cracks. The thick plate is affected by the combined stress of bending and shearing, showing three fracture patterns: long edge “O−X” cracks, short edge “O−X” cracks and “O−❋” cracks.

However, there are some limitations in the above-mentioned research. For example, in the actual mining process, existing studies are constrained by on-site monitoring technology and cannot track and monitor the entire process of crack propagation. Additionally, conventional finite element techniques do not effectively reproduce the full process of crack propagation and stress field evolution in the hard roof strata during the fracture process. In conclusion, the mechanisms of fracture processes in the roofs with different thicknesses, as well as the influence of tension-shear mixed modes on the fracture patterns of the goaf roof, have not been fully understood either theoretically or in engineering practice, and there is an urgent need for in-depth exploration from new perspectives.

Methodology

This study aims to investigate the fracture mechanics behavior of roofs with different thicknesses under uniformly distributed loads and four-sided fixed boundary conditions by using numerical simulation methods. Firstly, the finite element model of roofs with different thickness under uniform load and clamped boundary conditions was established, and the cohesive elements were inserted into the goaf roof. The failure process of cohesive element was simulated according to the maximum nominal stress criterion and the BK fracture criterion10. Secondly, the rationality of the model was verified by comparing the fracture effect of numerical simulation with the experimental results. Finally, based on the numerical simulation results obtained from the calibration, the influences of thick-span ratio, mesh size and lateral pressure coefficient on the crack morphology evolution and stress field were deeply analyzed, and the mechanical mechanism of the crack morphology evolution in the roofs with different thickness was revealed.

A rock constitutive model

Based on the extended Drucker-Prager (EDP) model, the plastic deformation of the matrix phase inside the rock is described, and the hyperbolic yield equation is written as11:

where \(F\) stands for the yield function, \({l}_{0}\) is the model parameter, \(q\) represents the Mises stress, \(p\) is the hydrostatic pressure, \(\phi\) is the friction angle of Drucker-Prager (DP) model, \({d}^{{\prime}}\) is the hardening parameter, and \({\sigma}_{c}\) is the uniaxial compressive strength. Here,

where \({\left.{d}^{{\prime}}\right|}_{0}\) and \({\left.{p}_{t}\right|}_{0}\) are the initial values of the hardening parameter and the hydrostatic tension strength of the material, respectively.

With the accumulation of damage, the plastic strain gradually increases and the equivalent yield stress \({\sigma}_{y}\) decreases. It is assumed that the attenuation law follows the exponential form10:

where ζ is the attenuation index, \(A\) and \(B\) are the model parameters. Given the initial yield stress \({\sigma}_{y0}\), the residual yield stress \({\sigma}_{yR}\) and the residual equivalent plastic strain \({\overline{\epsilon}}_{R}^{pl}\), then10:

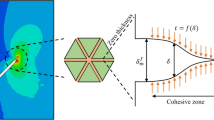

A cohesive zone model (CZM)

The cohesive zone model is mainly used to describe the mechanical behavior of the cements and particle interfaces in the thickness direction and two tangential directions. The maximum nominal stress criterion is utilized to signify the onset of initial damage in the cohesive element. Specifically, when the maximum nominal stress ratio, as defined in Eq. (5), reaches 1.0, the initiation of damage is considered. This criterion can be expressed as follows12:

where, \({t}_{n}\),\({t}_{s}\) and \({t}_{t}\) represent the nominal stress when the deformation is either purely normal to the interface or purely in the first or the second shear direction, respectively. \({t}_{n}^{0}\), \({t}_{s}^{0}\) and \({t}_{t}^{0}\) represent the peak values of the nominal stress when the deformation is either purely normal to the interface or purely in the first or the second shear direction, respectively. Here, the symbol \(\left\langle { } \right\rangle\) denotes the Macaulay bracket with its conventional interpretation. The application of Macaulay brackets serves to indicate that a purely compressive deformation or stress state does not trigger the initiation of damage.

The scalar damage variable \(D\) represents the damage of the cohesive element, with \(D\) monotonically increasing from 0 to 1. The damage evolution criterion is written as12:

where \({\overline{t}}_{n}\), \({\overline{t}}_{s}\) and \({\overline{t}}_{t}\) are the stress components predicted by the elastic Traction–Separation behavior for the current strains without damage.

The mixed mode of the deformation field in the cohesive zone is quantitatively determined based on the relative proportion of the normal deformation and the shear deformation. The fracture energy is defined as the triangular area enclosed by the Traction–Separation curve. Assuming that an equality in critical fracture energy for pure deformation along the first and second shear directions, denoted as \({G}_{s}^{C}={G}_{t}^{C}\), \([\text{mJ}\cdot{\text{mm}}^{-2}]\), the BK fracture criterion is used to describe the dependence of fracture energy on the combination of the mixed tensile-shear mode [13]:

where, \(\eta\) is the material parameter. \({G}_{n}\), \({G}_{s}\) and \({G}_{t}\) denote the proportion of the work done by the tractions and their conjugate relative displacements in the normal, first, and second shear directions, respectively.

General algorithm implementation of the CZM model

-

0.

Read material properties: \({K}_{nn}\), \({K}_{ss}\), \({K}_{tt}\), \({\sigma}_{nn}\), \({\sigma}_{ss}\), \({\sigma}_{tt}\), \({G}_{n}^{C}\), \({G}_{s}^{C}\), \(\eta\)

where \({K}_{nn}\), \({K}_{ss}\) and \({K}_{tt}\) denote the tensile and two shear stiffness, respectively. \({\sigma}_{nn}\), \({\sigma}_{ss}\) and \({\sigma}_{tt}\) represent the normal, first, and second shear nominal stresses.

-

1.

Give variables: \({{\updelta}}_{m}=statev\left(1\right)\), \({D}^{t}=statev\left(2\right)\), \(\beta=statev\left(3\right)\)

where \({{\updelta}}_{m}\) is the historical maximum displacement stored on the material point, \({D}^{t}\) is the damage parameter at the time “t”, \(\beta\) is the mixed-mode ratio of displacement, defined as14:

$$\beta = \frac{{u_{{shear}} }}{{u_{{shear}} + < u_{n} > }}$$(8)where \({u}_{n}\), \({u}_{s}\) and \({u}_{t}\) are defined as the displacements (or relative displacements) is either purely normal to the interface or purely in the first or the second shear direction, respectively. \({u}_{shear}=\sqrt{{\left({u}_{s}\right)}^{2}+{\left({u}_{t}\right)}^{2}}\). \(\left({G}_{s}+{G}_{t}\right)/\left({G}_{n}+{G}_{s}+{G}_{t}\right)\) is only a function of the mixed-mode ratio \(\beta\), it is defined as \(B\)14:

$$B=\frac{{\beta}^{2}}{1+2{\beta}^{2}-2\beta}$$(9)Compute: \({u}_{n}^{0}={t}_{n}^{0}/{K}_{nn}\), \({u}_{s}^{0}={u}_{t}^{0}={t}_{s}^{0}/{K}_{ss}\), \({\left\{u\right\}}^{t+1}={\left\{u\right\}}^{t}+{\left\{du\right\}}^{t+1}\). The direction cosines are defined as \(\text{cosI}\) and \(\text{cosII}\) as follows15:

$$\text{cosI}=\frac{\text{max}\left({u}_{n},0\right)}{\sqrt{{\text{max}\left({u}_{n},0\right)}^{2}+{\left({u}_{s}\right)}^{2}+{\left({u}_{t}\right)}^{2}}},\text{cosII}=\sqrt{1-{\left(\text{cosI}\right)}^{2}}$$(10) -

2.

Compute the mixed-mode onset displacement \({\delta}_{m}^{0}\) and final displacement \({\delta}_{m}^{f}\):

$${\delta}_{m}^{0}=\sqrt{{\left({u}_{n}^{0}\right)}^{2}+\left[{\left({u}_{s}^{0}\right)}^{2}-{\left({u}_{n}^{0}\right)}^{2}\right]{B}^{\eta}}$$(11)$$\delta _{m}^{f} = \frac{{2\left[ {G_{n}^{C} + \left( {G_{s}^{C} - G_{n}^{C} } \right)B^{\eta } } \right]}}{{\left[ {K_{{nn}} \left( {\cos {\text{I}}} \right)^{2} + K_{{ss}} \left( {\cos {\text{II}}} \right)^{2} } \right]{{\delta }}_{m}^{0} }}$$(12) -

3.

Compute equivalent displacement \(u_{m} = \sqrt {\left( { < u_{n} > } \right)^{2} + u_{{shear}} ^{2} }\), \({{\updelta}}_{m}=max\left({{\updelta}}_{m},{u}_{m}\right)\)

-

4.

The corresponding damage parameter d (at the time “t + 1”) for monotonic loading is calculated as15:

$${D}^{t+1}=d=\left\{\begin{array}{cc}0,&{{\updelta}}_{m}\le{\delta}_{m}^{0}\\\frac{{\delta}_{m}^{f}\left({{\updelta}}_{m}-{\delta}_{m}^{0}\right)}{{{\updelta}}_{m}\left({\delta}_{m}^{f}-{\delta}_{m}^{0}\right)},&{\delta}_{m}^{0}<{{\updelta}}_{m}<{\delta}_{m}^{f}\\1&{{\updelta}}_{m}\ge{\delta}_{m}^{f}\end{array}\right.$$(13) -

5.

Update stress and state variables

$$\left\{\begin{array}{c}{t}_{n}\\{t}_{s}\\{t}_{t}\end{array}\right\}=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}\left\{\begin{array}{cc}{K}_{nn},&{u}_{n}^{t}\le0\\{K}_{nn}\left(1-d\right),&{u}_{n}^{t}>0\end{array}\right\}&0&0\\0&{K}_{ss}\left(1-d\right)&0\\0&0&{K}_{tt}\left(1-d\right)\end{array}\right]\left\{\begin{array}{c}{u}_{n}\\{u}_{s}\\{u}_{t}\end{array}\right\}$$(14)$$statev\left(1\right)={\delta}_{m},statev\left(2\right)={D}^{t+1},statev\left(3\right)=\beta$$

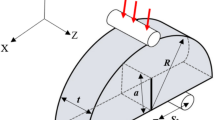

A finite element model

In order to study the influence of rock thickness on the roof breaking mode and visually observe the crack propagation law in the roof breaking process under the condition of uniform load and four-sided fixed support boundary, the Abaqus FEM software is used for simulation analysis. The model is 35 cm in length and 20 cm in width, and the central region is 30 cm in length and 16 cm in width. The unit system used in the geometric modeling is [mm], and the model is divided into three parts: concrete plates with different thicknesses, upper clamp plate and lower clamp plate (as shown in Fig. 1a). The concrete plate is divided into the central loading region and the surrounding fixed region, and the loading region and the fixed region are connected by “Tie contact”. The contact between the concrete plate and the clamp plates and the self-contact inside the concrete plate are connected by explicit “general contact”. To improve the calculation accuracy, local mesh refinement was applied to the goaf roof, and cohesive elements were globally inserted (as shown in Fig. 1b). The type of solid element is C3D8, and the material is hyperbolic Drucker-Prager elastoplastic material, utilizing Eq. (3) to simulate material softening behavior (the mechanical parameters are shown in Table 1, \(h\) is the thickness of the concrete plate). \(\rho\) is the density, \(\rho=1.69\text{g}\cdot{\text{cm}}^{-3}\). \(E\) and \(\mu\) are the elastic modulus and Poisson’s ratio of concrete plate, respectively. The cohesive element type is COH3D8, and the material is a linear elastic material with Traction-Separation behavior. The initial thickness of the cementation layer is set to 1.0 mm by default. The damage initiation criterion is the maximum nominal stress criterion, and the damage evolution criterion adopts the BK fracture criterion based on linear softening law of energy (the mechanical parameters are shown in Table 2). The values of fracture energy can refer to the study of quasi-brittle materials in type-II fracture toughness test16.

Boundary condition: The concrete plate is inserted between the two clamp plates, and the two clamp plates are set as the fixed constraints8. Uniform loads and are applied to the upper surface of the loading region and the left and right sides of the concrete plate, respectively.

Numerical simulation of the roof breaking process

Model validation

Crack distribution laws

Figures 2, 3 and 4 show the comparison between the calculation results (as shown in Figs. 2a, 3a and 4a respectively) and the experimental results (as shown in Figs. 2c, 3c and 4c respectively) of crack distribution on the bottom surface of the concrete plates with different thicknesses. Furthermore, in order to obtain the crack morphology and the mixed fracture modes, the failure cohesive elements during the breaking process were extracted and the distribution laws of the variable “MMIXDME” were given. “MMIXDME” refers to the mode mix ratio during damage evolution, and it is evaluated as \(1-{m}_{1}\). In general, it varies with time at a given integration point. This variable is set to \(-1.0\) before initiation of damage. Denoting by \({G}_{n}\), \({G}_{s}\), and \({G}_{t}\) the work done by the tractions and their conjugate relative displacements in the normal, first, and second shear directions, respectively, and defining \({G}_{T}={G}_{n}+{G}_{s}+{G}_{t}\), the mode-mix definitions based on energies are as follow:

When \({m}_{1}=1\), indicating complete tensile failure, the corresponding MMIXDME=0. When \({m}_{1}=0\), indicating complete shear failure, the corresponding MMIXDME = 1.

Analysis of the Figs. 2, 3 and 4 shows that under the action of tension, the transverse main crack appears on the bottom surface of the thin plate (20 mm), and the shear failure occurs on the upper surface boundary, resulting in a decrease in the bearing capacity of the boundary. Under the influence of settlement deformation, the tensile crack along the long edge is formed at the center of the bottom surface of the concrete plate, and a transverse “X” crack is formed by extending to the four corners, which is consistent with the development process of “O−X” fracture in the traditional “thin plate theory”. For the medium thick plate with a critical thickness of 45 mm, tension cracks appear in the center of the bottom surface along the long edge direction and expand to both sides. However, due to the lack development of shear cracks at the short edge of the upper surface boundary, the “X” crack bifurcation angle of the lower surface is small. Similar to the medium thick plate (45 mm), a transverse “X” crack with a smaller bifurcation angle is formed on the bottom surface of the thick plate (65 mm). In addition, due to shear cracks penetrating up and down, the long edges of concrete plate completely lose their load-bearing capacity, resulting in vertical cracks along the short edges under tensile stress, eventually forming the classic “O−❋” cracks.

Further analysis of Figs. 2b, 3b and 4b shows that there are three fracture modes for concrete plates with different thicknesses: pure tensile fracture mode at the bottom surface, mixed fracture mode around the “X” shape cracks, and pure shear fracture mode along the long edge boundary. (1) In the thin plate (20 mm), cracks along the long edge boundary initially appear as pure tensile cracks and are located in the center position of the long edge. Subsequently, “MMIXDME” continues to increase, and the cracks extend to the bottom surface, which shows a pure shear fracture mode. Additionally, the crack propagation changes the boundary conditions, causing the tensile cracks to bifurcate during the lateral expansion process and extend towards the four corners of the plate, ultimately transitioning from the pure tensile fracture mode to the mixed fracture mode (as shown in Fig. 2b). (2) At the critical thickness of the plate (45 mm), the fracture mode at the long edge boundary changes with increasing plate thickness. Mixed mode cracks appear at the center of the long edge on the upper surface, but do not extend downwards. Pure shear cracks appear at the center of the long edge on the bottom surface, but do not extend upwards, resulting in no significant changes in boundary conditions. Furthermore, the distribution laws of “MMIXDME” indicate that mixed mode cracks still concentrate around the “X” shaped crack (as shown in Fig. 3b). (3) In the thick plate (65 mm), along the long edge boundary, “MMIXDME”=1, which indicates that pure shear cracks completely penetrate along the thickness direction, resulting in the structure of the plate changing from a four-sided fixed support beam structure to a two-sided fixed support beam structure. Meanwhile, at the center of the bottom surface, “MMIXDME”=0, which indicates that the tensile cracks have been completely penetrated along the thickness direction (as shown in Fig. 4b).

Evolution laws of the maximum principal stress

Figures 5, 6 and 7 show the evolution laws of the maximum principal stress on the bottom surface of the concrete plates with different thicknesses during crack propagation. With the increase of thickness, the failure modes of thin plate and thick plate are different, and the evolution laws of maximum principal stress also change. Analysis of Figs. 5, 6 and 7 shows that at the initial stage of loading, the central position of the bottom surface is covered by tensile stress, showing a “saddle shape”. The maximum compressive stress is located at the interface between the loading region and the fixed support region, which shows shear failure mode. (1) In the thin plate (20 mm), a saddle-shaped tensile region is formed on the bottom surface, and the maximum tensile stress occurs in the center position (as shown in Fig. 5a). At the time t = 2340 s, the transverse tensile cracks begin to appear and spread to both sides of the long edge. With the release of strain energy, an “X” type stress release region is formed in the central position (as shown in Fig. 5b). At the time t = 2460 s, the transverse tensile cracks stop expanding, and then bifurcate along the “X” stress release region, resulting in an “X” type crack. At the same time, the tensile region is segmented by an “X” shape crack (as shown in Fig. 5c). With the appearance of shear cracks, the bearing capacity of the long boundary decreases, and the boundary conditions of the four sides are also changed. At the time t = 3000 s, the tensile region shows an hourglass shape (as shown in Fig. 5d). (2) In the critical thickness plate (45 mm), the crack evolution laws are similar to that of thin plate. Firstly, a transverse “X” crack is formed on the bottom surface under tensile action (as shown in Fig. 6a). At the time t = 1680 s, with the formation of the transverse main crack, the strain energy on the bottom surface is released, and the “C” shaped tensile stress concentration regions are formed on the left and right sides (as shown in Fig. 6b). At the time t = 2580 s, similar to Fig. 5b, an “X” shaped tension stress release area begins to appear (as shown in Fig. 6c). At the time t = 3000 s, comparing Figs. 5d and 6d, it can be observed that, unlike thin plate, the tensile region of the critical thickness plate does not extend along the short edge. Analyzing Figs. 2b and 3b, for the thin plate and the critical thickness plate, there are tensile-shear mixed mode cracks on the upper surface and pure shear cracks on the bottom surface at the long edge boundary. However, no phenomenon of crack propagation along the thickness direction was observed in the latter, which resulted in differences in the weakening of boundary conditions. (3) In the thick plate (65 mm), similar to the thin plate, the bottom surface of the thick plate is covered by tensile stress at the beginning of loading (as shown in Fig. 7a). At the time t = 2220 s, the transverse tensile cracks appear in the central position and extend along the long side to the boundary. Unlike the thin plate, there is no “X” shaped stress release region observed at the center position (as shown in Fig. 7b), apparently due to the two different crack modes. At the time t = 2880 s, the tensile stress is released in the central position, forming an: “O” type tensile stress region (as shown in Fig. 7c). At the time t = 3000 s, the tensile stress is released along the short edge, showing an “H” type distribution characteristic (as shown in Fig. 7d). In addition, a large number of pure shear cracks are appeared in the long edge boundary (as shown in Fig. 4b), and the compression-shear region is transferred towards the short edge boundary, and the “O−❋” crack begins to form.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis of grids

The numerical simulation method based on the cohesive zone model needs to insert cohesive elements between solid elements, which increases a large number of interface elements and requires more computation than the traditional mesh partitioning method. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the mesh size reasonably to ensure the simulation accuracy and improve the calculation efficiency. Figure 8 shows the crack propagation and maximum principal stress distribution laws on the bottom surface of the thick plate (65 mm) under different mesh sizes. It can be seen that, under different mesh sizes, the transverse expansion of the main crack does not change in shape (as shown in Figs. 8a and 8b) and the maximum principal stress distribution is also “H” shape, which has little influence on the study of the main crack growth morphology and formation mechanism, but greatly increases the calculation time. In addition, Figs. 8c and 8d show that when the mesh size is 3.0 mm, the maximum tensile stress and compressive stress are 8.01 MPa and 46.01 MPa, respectively. When the mesh size is 2.5 mm, the maximum tensile stress and compressive stress are 8.49 MPa and 57.78 MPa, respectively. The relative errors are 5.7% and 20.4%, respectively, which showed an obvious compressive stress sensitivity. This is because the CZM model assumes no damage in the direction of compression, as shown in Eq. (6). In the follow-up study, in order to accurately calculate the mechanical behavior of the cohesive elements under compression, the CZM model considering the tension-compression-shear mixed mode should be proposed.

Sensitivity analysis of the lateral pressure coefficient

The working face of deep coal seam is always in the complex stress state caused by the overlying strata’s self-weight, tectonic stress, and excavation unloading. Therefore, studying the fracture patterns of thick and hard roof strata under different stress conditions is of significant importance for researching the instability of rock masses. Figure 9 shows the crack distribution laws on the bottom surface of the thick plate under different lateral pressure coefficients. According to the parameter settings of the calculation model, Fig. 4a correspond to the special case where the lateral pressure coefficient is 1.0. The calculation results indicate that the fracture modes change with the variation of the lateral pressure coefficient (as shown in Figs. 9a and 9b). Compared with Figs. 9c and 9d, it can be seen that with the increase of the lateral pressure coefficient, the tensile crack decreases significantly at the left bifurcation position of the bottom surface of the thick plate, but begins to develop at the center position of the plate and expands along the thickness direction. In addition, it was found that the number of shear cracks along the long boundary increased significantly and were completely penetrated along the thickness direction. The above results show that the horizontal stress inhibits the expansion of the bottom tensile crack, but promotes the shear failure at the long edge boundary and intensifies the bending failure tendency.

Conclusions

In this paper, the failure behavior of cohesive elements is studied by using the cohesive element technology, combined with the maximum nominal stress criterion and the BK fracture criterion. We conducted the fracture mechanical behavior of roofs with different thicknesses under four-sided clamped boundary and uniform load by the numerical simulation. The research results reveal the mechanical mechanism of the “O−X” and the “O−❋” fracture morphology evolution of roofs with different thickness, and the influence of roof thickness-span ratio on fracture morphology evolution and stress field was analyzed in depth. The main conclusions are as follows:

-

1.

There are three fracture modes of concrete plates with different thickness: pure tensile fracture mode at the bottom surface, mixed fracture mode around the “X” shape crack, and pure shear fracture mode along the long edge boundary. The thin plate shows the transverse “O−X” crack pattern, while the thick plate shows the “O−❋” crack pattern. In summary, with the increase of thickness, the tensile-shear failure mode gradually transitions from tension to shear, leading to changes in crack paths and failure modes.

-

2.

At the initial stage of loading, the central position of the bottom surface is covered by tensile stress, showing a “saddle shape”. The maximum compressive stress is located at the interface between the loading region and the fixed support region, which shows shear failure. With the increase of applied loads, the evolution laws and failure patterns of the maximum principal stress of concrete plates with different thicknesses are also different. In the thin plate, the tensile stress is mainly concentrated around the crack bifurcation position during crack propagation, which is segmented by the “X” crack. In the thick plate, the tensile stress shows an “H” type distribution characteristic. This is because the shear failure occurs along the long edge, and the stress concentration area along the short edge is eventually formed, showing a typical “❋” crack morphology. In summary, the formation and propagation of cracks on the bottom surface are controlled by the evolution laws of the tensile stress. With the thickness increases, the shear failure intensifies, and the crack paths may change. The cracks along the long edge begin to penetrate up and down, which changes the boundary conditions and the stress distribution laws in the loading region, and promotes the formation of cracks along the short edge, which is manifested as the failure law of tension-shear mixed mode.

-

3.

The bilinear cohesive zone model assumes that there is no damage in the compression direction, while the evolution of compressive stress is controlled by solid elements, which shows obvious grid sensitivity of compressive stress. Therefore, in order to accurately predict the evolution of stress, a cohesive zone model considering the tension-compression-shear mixed mode needs to be proposed in the following work. Sensitivity analysis of the lateral pressure coefficient indicates that the fracture modes change with the variation of the lateral pressure coefficient. The horizontal stress inhibits the expansion of the tensile cracks on the bottom, but promotes the shear failure at the loading boundary, and increases the bending failure tendency.

In conclusion, this paper established a FEM model to simulate roof breakage, reproduces the failure modes of the roofs with different thicknesses under four-sided clamped boundary conditions and uniform loads, and verifies the effectiveness of the model through experimental data. The fracture modes of the roofs are closely related to factors such as mining pressure, gas extraction, underground water movement, and surface subsidence. Studying the fracture patterns of the roofs will provide a theoretical basis for predicting roof accidents and supporting roof protection. However, the complex geological conditions pose challenges for predicting roof breakage in advance. By using this model to simulate the breakage patterns of roof with different thickness-to-span ratios numerically and combining it with on-site measurements, guidance can be provided for roof support and techniques such as cutting and unloading the roof to enhance mine safety levels. Additionally, in practical engineering, the rock material is non-homogeneous and contains initial defects, necessitating consideration of influences such as weak interlayers or inherent fractures. Further research is needed to incorporate these characteristics into the model to more comprehensively reflect the actual roof breakage during the coal seam exploitation process. Furthermore, the issue of roof breakage and dynamic mining pressure is the result of the combined effects of multiple critical rock layers. Studying the breakage of a single rock layer may not be sufficient to address the challenges posed by multiple key layers. Therefore, it is necessary to deeply study and solve these problems in the future work.

Data availability

All data used in this study is available in the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- F :

-

Yield function, [MPa]

- p :

-

Hydrostatic pressure, [MPa]

- \(\sigma_{c}\) :

-

Compressive strength, [MPa]

- \(\phi\) :

-

Friction angle, [°]

- \(\zeta\) :

-

Attenuation index, [1]

- \(T\) :

-

Traction force, [N]

- \(\sigma\) :

-

Nominal stress, [MPa]

- \(G^{C}\) :

-

Fracture energy, [mJ mm−2]

- \(E\) :

-

Elastic modulus, [GPa]

- \(K\) :

-

Stiffness, [GPa]

- \(\beta\) :

-

Mixed-mode ratio of displacement, [1]

- \(\delta_{m}^{0}\) :

-

Mixed-mode onset displacement, [mm]

- \(l_{0} ,{ }d^{\prime}\) :

-

EDP model parameter, [MPa]

- \(q\) :

-

Mises stress, [MPa]

- \(\sigma_{y}\) :

-

Yield stress, [MPa]

- \(\psi\) :

-

Dilation angle, [°]

- \(\overline{\varepsilon }^{pl}\) :

-

Equivalent plastic strain, [1]

- \(\varepsilon\) :

-

Nominal strain, [1]

- \(\mu\) :

-

Poisson’s ratio, [1]

- \(\rho\) :

-

Density, [g cm−3]

- \(h\) :

-

Thickness, [mm]

- t :

-

Time, [s]

- B :

-

Mixed-mode ratio of fracture energy, [1]

- \(\delta_{m}^{f}\) :

-

Mixed-mode final displacement, [mm]

References

Yao, W., Wang, E., Liu, X. & Zhou, R. Fracture distribution in overburden strata induced by underground mining. Deep Undergr. Sci. Eng. 1(1), 58–64 (2022).

Wang, G., Wu, M. M., Wang, R., Xu, H. & Song, X. Height of the mining-induced fractured zone above a coal face. Eng. Geol. 2017, 140–152 (2017).

Wang, P., Jiang, J. Q., Zhang, P. P. & Wu, Q. L. Breaking process and mining stress evolution characteristics of a high-position hard and thick stratum. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 26, 563–569 (2016).

Pu, H., Huang, Y. G. & Chen, Y. G. Mechanical analysis for X-O type fracture morphology of stope roof. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 40(6), 835–840 (2011). (in China).

Li, X. L., Liu, C. W., Liu, Y. & Xie, H. The breaking span of thick and hard roof based on the thick plate theory and strain energy distribution characteristics of coal seam and its application. Math. Probl. Eng. 8, 1–14 (2017).

Gao, F. Q., Stead, D. & Coggan, J. Evaluation of coal longwall caving characteristics using an innovative UDEC Trigon approach. Comput. Geotech. 55, 448–460 (2014).

Ning, J. G. et al. Fracture analysis of double-layer hard and thick roof and the controlling effect on strata behavior: A case study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 81, 117–134 (2017).

Zuo, J. P. et al. Analysis of surface cracking and fracture behavior of a single thick main roof based on similar model experiments in western coal mine, China. Nat. Resour. Res. 30(1), 657–680 (2020).

Zuo, J. P. et al. Experimental investigation on fracture mode of different thick rock strata. J. Min. Strata Control Eng. 1(1), 013007 (2019). (in China).

Zhang, X. F., Zhang, N., Li, X., Liu, C. C. & Chen, Y. Numerical simulation of a failure pattern of the roof in coal seam working face. Therm. Sci. 28(2A), 1149–1154. https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI230615038Z

Wang, Y. Y. Abaqus Analysis User’s Guide. Material Volume (China Machine, 2018).

Simulia, D. C. S. Abaqus 6.11 analysis user’s manual (2011).

Benzeggagh, M. L. & Kenane, M. Measurement of mixed-mode delamination fracture toughness of unidirectional glass/epoxy composites with mixed-mode bending apparatus. Compos. Sci. Technol. 56(4), 439–449 (1996).

Turon, A. et al. A damage model for the simulation of delamination in advanced composites under variable-mode loading. Mech. Mater. 38(11), 1072–1089 (2006).

Jiang, W. G. et al. A concise interface constitutive law for analysis of delamination and splitting in composite materials and its application to scaled notched tensile specimens. Int. J. Numer. Meth Eng. 69, 1982–1995 (2007).

Afrazi, M., Lin, Q. & Fakhimi, A. Physical and numerical evaluation of mode II fracture of quasi-brittle materials. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 20, 993–1007 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Taishan Industrial Experts Program (NO. TSCX202408130), the Shandong Energy Group (No. SNKJ2022A01-R26).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Wei Li, Xiu-Feng Zhang, Yue-Yong Han, Feng Gao, Ning Zhang and Xiang Li; methodology, Feng Gao, Ning Zhang and Xiang Li; validation, Ning Zhang and Xiang Li; investigation, Yang Chen, Chuan-Cheng Liu, Guang-Peng Li, Bao-Qi Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Wei Li, Ning Zhang and Xiang Li; writing—review and editing, Feng Gao and Ning Zhang; funding acquisition, Xiu-Feng Zhang.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Zhang, XF., Han, YY. et al. Numerical simulation of fracture patterns in roof strata with different thicknesses. Sci Rep 14, 28899 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80478-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80478-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Study on roof partition fracture based on dominant primary fracture

Scientific Reports (2025)