Abstract

Weather recognition is crucial due to its significant impact on various aspects of daily life, such as weather prediction, environmental monitoring, tourism, and energy production. Several studies have already conducted research on image-based weather recognition. However, previous studies have addressed few types of weather phenomena recognition from images with insufficient accuracy. In this paper, we propose a transfer learning CNN framework for classifying air temperature levels from human clothing images. The framework incorporates various deep transfer learning approaches, including DeepLabV3 Plus for semantic segmentation and others for classification such as BigTransfer (BiT), Vision Transformer (ViT), ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and DenseNet121. Meanwhile, we have collected a dataset called the Human Clothing Image Dataset (HCID), consisting of 10,000 images with two categories (High and Low air temperature). All the models were evaluated using various classification metrics, such as the confusion matrix, loss, precision, F1-score, recall, accuracy, and AUC-ROC. Additionally, we applied Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to emphasize significant features and regions identified by models during the classification process. The results show that DenseNet121 outperformed other models with an accuracy of 98.13%. Promising experimental results highlight the potential benefits of the proposed framework for detecting air temperature levels, aiding in weather prediction and environmental monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prediction of weather phenomena significantly impacts several domains, including environmental monitoring, weather prediction, and the evaluation of environmental quality1. Both natural processes and human activities contribute to global climate change, resulting in extended alterations in weather patterns2. Many climate events such as snow, sandstorms, and haze exert substantial influence on autonomous driving systems3, and also have profound effects on our daily routines, travel patterns, and choice of attire4. Severe weather conditions pose significant hazards to traffic, leading to accidents on highways caused by intense rainfall, snow showers, thick fog and sandstorms5,6. Furthermore, weather conditions also can have diverse effects on agriculture process7. The contemporary weather phenomena can influence the weather conditions of subsequent days8. Additionally, the temperature fluctuations have caused extreme climate challenges9. The rising air temperatures contribute to climate change alongside with several other factors, leading to extensive consequences including rise seawater-level rising, raised rate of severe events, and increased global warming10. The extreme hot and cold temperatures have caused in critical impacts on mortality rates11. Furthermore, intense health concerns in populations have been linked with departures from the suitable range of air temperatures12,13. The existing research has discovered that there exists a link between air temperature and daily fatalities in metropolitan areas14. Air temperature is an essential factor in climate change as it directly impacts atmospheric processes, weather patterns, and ecosystems. Therefore, predicting and understanding air temperature is important in order to address the impacts of climate change.

Meteorologists typically utilize thermometers, satellite imagery, and weather forecast models to measure air temperature. The estimating temperatures over diverse locations commonly involves collecting large-scale data and using complex algorithms, potentially compromising accuracy. Moreover, fluctuating environmental conditions and inadequate sensor coverage can supplementary challenge the precision of these estimates. Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionizing various domains, including computer vision, remote sensing and environmental science, by enabling more accurate climate modeling, wildlife monitoring, and natural resource management. The rapid progress of machine learning in AI, nowadays allows researchers to actively employ it across various academic fields15 proposed a method based on and Least Squares Support Vector Machine and Empirical Mode Decomposition for air temperature prediction.16 developed an Xgboost model to accurately estimate the outdoor air temperature. Besides, Ref.17 proposed an innovative nonparametric technique based on random forest to estimate outdoor temperatures. The model employed data gathered at NUS’s Kent Ridge campus from February to July 2019. However, ordinary machine learning faces difficulties in accurately acquiring the characteristics of weather phenomena for weather phenomenon recognition. Deep learning methods revolutionizes machine learning by utilizing complex neural networks to process huge amounts of data, achieving supreme accuracy in jobs like image recognition and natural language processing18.

The Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is a deep learning method renowned for its prowess in representing image features due to its utilization of a deep model structure with convolutional kernels, pooling operations, and other relevant mechanisms19,20. The CNN, pioneered by AlexNet’s success in the ImageNet Large-Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC), has become a foundational model across various research domains such as continuous prediction21, object detection22, and face recognition23. Recently, many researchers have been applying CNN models to atmospheric issues. Reference24 employed CNNs to perform snow cover extraction from earth observation data. Two models were developed based on CNNs, demonstrating improved accuracy in cloud recognition tasks25. A framework with a lightweight deep structure was proposed, integrating daytime and nighttime image segmentation. This approach was applied to public databases, resulting in improved results26. In conclusion, it can be seen that CNNs are preferred and offer distinct advantages in meteorological research and the classification of weather phenomena. Recently, several studies have employed CNNs for weather phenomena classification, achieving the highest accuracy and demonstrating effective performance27. These studies have successfully addressed tasks such as sunny and cloudy classification4 and the classification of weather into three classes: rainy, foggy, and snowy28. Reference29 successfully developed a deep classification model capable of accurately classifying six classes of weather events, encompassing rain, snow, haze, frozen, dust and dew. Another study effectively utilized a three-channel CNN for the classification of weather phenomena into six classes30. Besides, Ref.31 developed a multi-classification model for weather phenomena recognition. However, these studies only focus on a limited number of weather phenomena and lack accuracy. There exists a wide array of weather conditions in our daily lives, each varying significantly. Therefore, it is essential to incorporate additional types of weather phenomena for analysis and recognition.

To the best of our knowledge, previous research has not extensively addressed the prediction of air temperature based on human clothing images using deep learning techniques. As we know that, Humans efficiently adjust their clothing on their bodies in response to temperature conditions to achieve optimal thermal comfort32. Furthermore, clothing serves as a portable environment, allowing individuals to adapt to various settings, indoors or outdoors, by regulating their microclimate economically and sustainably33,34. Therefore, in this study, we utilized images of human clothing to classify air temperature levels into two categories: high temperature and low temperature, employing a deep transfer learning convolutional neural network framework. Our research represents a significant advancement in the field of weather recognition, offering a novel, precise, and practical solution for classifying air temperature based on images of human clothing. This method holds promise for applications in diverse domains such as weather prediction, environmental monitoring, tourism, building management systems, and energy production.

In this paper, we present a deep transfer learning framework designed for the classification of low and high-level temperatures using human clothing images. Secondly, we have created a Human Clothing Image Dataset (HCID) consisting of 10,000 images, with each category comprising 5000 images. Thirdly, we apply transfer learning techniques on customizing proposed models, and evaluate the performance with several metrics. Additionally, we employ the Grad-CAM test to visualize feature maps across the layers of the models. The remainder of the paper is organized into the following sections: Section "Methodology" presents the methodology and dataset, Section "Results and discussion" presents the results and discussion, and Sect. “Conclusion” provides the conclusion of this paper.

Methodology

Deep learning is a rising area with numerous successful applications recently. It helps scientists in many domains. Deep learning has made it significantly easier to forecast and address problems in artificial intelligence (AI). CNNs have received significant attention in the field of image classification research because of their remarkable accuracy. Additionally, it effectively extracts image features and patterns, thereby improving classification accuracy. Since its inception, it has been utilized in image processing. Recent advancements in deep learning, especially in the climate and environmental domain, suggest that several deep CNN structures can be utilized. This study initiates with a comprehensive analysis of different baseline models including Big Transfer (BiT), Vision Transformer (ViT), ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19 and DenseNet121. In this study, we maintain standard convolution specifications for all baseline ImageNet models. Human-clothing images are input into the model, and images of various sizes are resized to the same dimensions. The proposed deep learning system is showed in Fig. 1.

Dataset description

The dataset comprises images of individuals captured across varied locations and under diverse weather conditions. Two hundred students participated in this study, including undergraduates, graduates, and postgraduates. Their historical images were collected for analysis and experimentation. The dataset consists of 10,000 images acquired from participants and categorized into two groups: Low Temperature and High Temperature. Figure 2 displays eight images of two distinct categories from the HCID dataset. The first row, consisting of images (a), (b), (c), and (d), corresponds to high temperatures, whereas the second row, comprising images (e), (f), (g), and (h), corresponds to low temperatures. Images of individuals associated with low temperatures are classified within the Low category, whereas those linked with high temperatures are categorized under the High category. The Low class comprises 5000 images, while the High class contains 5000 images. For model training, 80% of the dataset was utilized, with the remaining 20% reserved for testing. Table 1 provides this information.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all participants (or their legal guardians) involved in the study for the use of their clothing images for research and publication purposes. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Participants were thoroughly informed about the objectives of this study, the nature of the images collected, and how their data would be utilized, including potential publication in academic contexts. The study emphasized the importance of privacy, ensuring that all images were anonymized to protect the identity of individuals. No personally identifiable information was included in the dataset, and strict measures were taken to maintain confidentiality throughout the research process.

Data preprocessing

Image preprocessing is an essential stage in working with image datasets. In this proposed work, we have utilized deep learning to create binary classifier for human clothing images to predict the presence of temperature levels. Due to difference sizes of images, we resized all images to 520 × 520 × 3 dimensions to preserve uniformity for all models. Images with human appearances also contain background elements with various objects, such as buildings, vehicles, roads, tables, chairs, and several objects, which affect the accuracy of models. DeepLabV3 Plus was then applied to the entire dataset for semantic segmentation with the “Person” (Class-15). Figure 3 illustrates examples of result images segmented with the “Person” class. Rows (1), (2), (3) and (4) represent different examples, while columns (a), (b), (c), and (d) represent different stages of processing. Column (a) shows the original input image fed into DeepLabV3 Plus, and Column (b) displays the overlay of the “Person” class generated by the model, while Column (c) depicts the application of the mask corresponding to the “Person” class. Finally, Column (d) presents the masked image, which serves as the final input for training models for temperature classification. Following segmentation, we transformed all images into pixel arrays, normalized them to a scale ranging from 0 to 1, and categorized them based on their source directory, assigning labels respectively.

Data augmentation is a technique utilized to expand datasets, facilitating enhanced feature learning on a larger scale, mitigating overfitting and boosting generalization in models. It contains several parameters in augmentation process. For example, we randomly adjusted the color saturation, hue, and brightness values for all training images. Affine transformation was performed to each image with rotation of 0 to 30. The selected shearing and zooming scale was 0.2, and we made brightness level adjustments ranging from 0.75 to 1.25.

Pre-trained models and transfer learning

Training models from scratch requires a sizable dataset, ample resources, and significant computational power. The (HCID) dataset was utilized with transfer learning to produce an accurate and wide range of feature set to operate. Since, the most datasets containing images of people are relatively small, requiring more time to develop an efficient model. Therefore, pre-trained models were adapted and customized to create the proposed models for predicting air temperature.

DeepLabV3 plus

The DeepLab network solves image segmentation scales with Atrous convolution method. DeepLabV1 is a technique that integers CNNs and probabilistic graphical models for Object delineation35. DeepLabV2 utilizes Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP), employing an expanded convolutional structure with varying proportions36. DeepLabV3 presented enhancements to the ASPP component37. The DeepLabV3 Plus model combines CNNs with atrous convolution to perform image segmentation tasks. The model widens the convolutional receptive field without adding parameters, balancing speed and accuracy. Moreover, DeepLabV3 Plus employs ASPP (Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling) for semantic segmentation, enhancing its performance in this area. It processes and encodes input image features through convolutions with multiple expansion rates and operational fields of view, followed by a pooling operation to capture context across various scales. In DeepLabV3 Plus, a decoder is introduced which actively compresses low-level features, thereby diminishing their relative representation compared to DeepLabV3. The ASPP module processes the feature map by up-sampling to match low-level feature resolution, applying a 3 × 3 convolution, and then up-sampling again to restore spatial information, efficiently capturing refined target boundaries in images for prediction of semantic segmentation38. The architecture of the DeepLabV3 Plus model for semantic segmentation with Person class depicted in Fig. 4.

BigTransfer (BiT)

Big Transfer (BiT) was introduced by Google Research’s Brain team in 2019, a cutting-edge technique for computer vision tasks39. Recently, BiT is so popular due to strong transfer ability. It consists capability to perform even on tiny image datasets with less number of labels. Generally, most researchers in deep learning area accepted models with large scale architecture for better performance. Because large architecture models perform well compared to models with smaller architectures. Moreover, it achieves higher generalization due to being trained on large datasets. BiT applies the potency of scale through the upstream (pre-training) stage. Essentially, it employed large datasets and a high-performing model architecture for its training process. Consequently, this provides the better performance in downstream tasks (new tasks adjusted through fine-tuning) by leveraging well-trained weights. Moreover, BiT uses group normalization (GN) instead of batch normalization40, which is popular in convolutional deep learning models, in order to achieve computational efficiency on large-scale datasets. In addition, it employs weight standardization technique41 to avoid numerical abilities during the weight updates.

Resnet101

The detailed description of ResNet topologies is provided in this work42. In this design of the network, convolutional and pooling layers were sequentially layered in a vertical stack. This can lead to a decline in network performance as a result of vanishing gradient issues. Hence, networks with residual blocks, which incorporate shortcut connections, can significantly improve performance by mitigating training errors in deep architectures. ResNet101 is variant of ResNet structure with 101 layers.

Vision transformer (ViT)

The architecture of the Vision Transformer is based on the Vanilla Transformer, which has recently attracted many researchers due to its demonstration of cutting-edge performance in machine learning field43. The ViT architecture utilizes an encoder-decoder system with a parallel mechanism that can process sequential data without depending on any recurrent networks. The efficiency of transformer models can be attributed significantly to the self-attention mechanism. This mechanism is specially designed to detect and understand the long-distance connections among sequence elements. The ViT structure was introduced to adapt standard transformer model for image classification tasks. The primary goal is to generalize across modalities without integrating data specific architectures. The Vision Transformer uses the encoder for image classification, transforming image patches into semantic labels. Contrasting traditional CNNs that only focus on local areas with filters, it employs an attention mechanism to consider the entire image, allowing a comprehensive analysis of visual content.

DenseNet121

The DenseNet architecture, introduced by Gao Huang et al. in 201744, utilizes dense connections, where each layer is directly connected to every other layer, enabling efficient reuse of features across the network. This interconnected structure guarantees that each layer is influenced by the parameters and feature maps of the preceding layers. Additionally, this structure enables feature reuse, where layers share features learned by earlier layers, reducing redundancy and improving efficiency. This helps the model capture complex patterns with fewer parameters, leading to better performance. There are several variants of the DenseNet architecture frequently used by researchers in image classification tasks, one of them is DenseNet121, which consists of 121 layers and is utilized in this study.

VGG16 & VGG19

The VGGNet architecture, introduced in 2014 by the University of Oxford’s Visual Geometry Group45, is a highly popular deep convolutional model. It achieved both first prize and second place in image classification at the ILSVRC 2014. The initial idea was to design this model to perform accurate image processing tasks with various kernels. Recently, researchers have widely utilized the VGG architecture to extract deep image patterns and features across different domains for further processing in computer vision tasks. VGG16 consists of 16 layers, whereas VGG19 comprises 19 layers within its architecture.

The proposed models with customization

Following the preprocessing step, the dataset was partitioned into two subsets: 80% allocated for training the models, while the remaining 20% was reserved for testing purposes. Neural networks can be applied on different types of data tasks, CNNs are one of them, specially designed for image classification. Most research employs CNNs for the analysis of visual imagery and often plays a vital role in image classification. The Python package TensorFlow, a deep learning framework, was used to train CNNs using the Keras library. Due to the large size of the ImageNet dataset, that covers approximately 1.2 million images, it is often used to build numerous architectures for generating general models. To achieve generalization beyond ImageNet, transfer learning techniques are applied in this study. This can only be done with pre-trained models. Fine-tuning was also applied to pre-trained models to capture changes. We constructed our models utilizing a variety of architectures, such as BigTransfer (BiT), ResNet101, Vision Transformer (ViT), DenseNet121, VGG16, and VGG19. For instance, the VGG19 convolutional neural network (CNN) incorporates a 2D Max Pooling layer yielding an output shape of (7, 7, 512) with zero parameters, and it can be imported via the Keras applications class. Transfer learning was employed to address a two-class classification problem distinguishing between high and low temperatures. This involved modifying the output layer to function as a binary classifier. The system retrieved the outputs from the preceding layer and fed them into a flatten layer with a default shape of (7, 7, 512), following the max pooling output layer, resulting in a flattened matrix with dimensions of 7 × 7 × 512, totaling 25,088. We generally perform this flattening of rectangular shapes at the end of CNN, as they cannot directly input into the network. We introduced a dropout layer as a regularization technique to mitigate overfitting and improve generalization error. As our goal is to create a binary classifier, so we set the dropout value to 0.25 for the layer, a common choice. This principle is based on the observation that expansive neural networks often face an overfitting problem when trained on small datasets, leading to a reduction in validation accuracy. The customization of the proposed transfer learning model is illustrated in Fig. 5.

The output layer was introduced with two dense layers and a sigmoid function for predicting high and low temperature levels. The sigmoid function is used at the output layer to forecast a multinomial probability distribution for neural network models. Because we have a binary classifier that requires two dense layers, the Adam optimizer and the categorical cross-entropy loss function were utilized to build the model. The CNN employs cross-entropy loss during training to compute class probabilities for each image, facilitating probabilistic image classification.

Performance metrics

In this study, we evaluate our proposed models through classification, employing metrics such as Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, F1-Score, Precision, Recall, and ROC-AUC. These evaluation metrics are valuable for assessing the temperature classification system based on images. These metrics can be mathematically expressed as follows:

Results and discussion

Model training

The proposed models underwent training and testing procedures utilizing the PyTorch deep learning framework. The computer configuration for the models employed dual CPUs with Intel Core i5 processors, equipped with 32 GB of RAM, and a 1024 GB hard disk. In this work, we selected the hyper-parameters based on prior research and carried out several experiments. The Adam optimizer integrates the advantages of the AdaGrad and RMSProp algorithms while consuming less memory compared to other optimization approaches. As a result, The Adam optimizer enhances the optimization of the cross-entropy loss. To ensure optimal training of the proposed models, the training process involves selecting an initial learning rate of 0.0001, a batch size of 64, and a validation frequency of 10, spanning 200 epochs. Table 2 illustrates the model parameters, and all six models are executed with an identical experimental setup.

Experiment outcomes and analysis

The accuracy and loss graphs

The accuracy and loss graphs serve as crucial tools for visualizing model performance during the training phase. Figure 6a,b illustrates the training and validation losses, while Fig. 7a,b depicts the training and validation accuracies. Observing Fig. 6a,b demonstrates a rapid decrease in both training and validation losses, indicating optimal classification performance. Additionally, in Fig. 7a,b, it becomes evident that the models achieved comparable accuracies after a few epochs.

The ROC curve and AUC

The ROC curve serves as a pivotal tool for evaluating the performance of classification models46. Within the ROC curve diagram, each point delineates a pair of values: The False Positive Rate (FPR) on the x-axis and the True Positive Rate (TPR) on the y-axis. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) quantifies the entirety of the area encompassed by the curve, providing a comprehensive measure of model performance. The performance improvement of a classification model is indicated by the proximity of its ROC curve to the upper-left corner, and a greater area under the curve corresponds to superior classification outcomes. It can be observed from Fig. 8 that DenseNet121 achieved the highest AUC of 0.96, demonstrating the best ROC curve among all models.

Confusion Matrix (CM)

The confusion matrix is specifically employed to evaluate classification problems47. Figure 9 shows the confusion matrix of predicted results generated by proposed models including BigTransfer(BiT), Vision Transformer(ViT), ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and DenseNet121. The horizontal axis of the confusion matrix represents the predicted class labels, typically denoted as 0 and 1, corresponding to the test set. Meanwhile, the vertical axis signifies the actual class labels of the test samples, also represented as 0 and 1 respectively. Where 0 signifies the High class and 1 indicates the Low class category. In the confusion matrix, the predicted values of the model correspond with the actual values of the test samples along the diagonal. In Fig. 9, the diagonal values denote the count of accurately classified images corresponding to different temperature levels, whereas the values outside the diagonal indicate the count of misclassified images across temperature levels. For example, out of the total test samples, 712 (representing 47.47%) instances associated with class 0 (High Temperature) were accurately classified by the BigTransfer (BiT) model. However, in the same dataset, there were 55 samples (equating to 3.67%) originally categorized as class 0 (High Temperature) that were misclassified as class 1 (Low Temperature) by the BiT. It can be seen that, among the six models, DenseNet121 achieved the highest correct classification rate, with a (TN) value of 706 (47.07%) and a (TP) value of 736 (49.07%). It also had a relatively low misclassification rate, with a (FP) value of 26 (1.73%) and a (FN) value of 32 (2.13%). On the other hand, BigTransfer (BiT) demonstrated a high misclassification rate, with a (FP) value of 55 (3.67%) and a (FN) value of 60 (4%). It achieved a (TN) value of 712 (47.47%) and a (TP) value of 673 (44.87%). The remaining models, including Vision Transformer (ViT), ResNet101, VGG16, and VGG19, showed moderate misclassification and correct classification rates. Overall, these findings indicate that DenseNet121 is the most effective model for classification of air temperature levels from mobile images, while BigTransfer is the least accurate and the remaining models, namely Vision Transfer (ViT), ResNet101, VGG16, and VGG19, showed an average level of performance. The performance indicators for the proposed models for each class (0 and 1) are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Comparative analysis of model performance for air temperature classification from clothing images

The analysis of the performance metrics provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of various deep learning models in classifying air temperature based on human clothing images. The models compared include BiT, ViT, ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and DenseNet121. Among these, DenseNet121 consistently outperformed the others across all key performance metrics, such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, precision, recall, and AUC. These results highlight the advantages of DenseNet121 architecture, which are instrumental in achieving its superior performance.

DenseNet121 achieved the highest accuracy at 98.13%, along with the highest sensitivity (97.83%) and specificity (98.44%). These metrics indicate that DenseNet121 not only correctly identifies the majority of true positive instances but also excels in minimizing false positive cases. The F1-score of 97.05% and AUC of 98.14% confirm a robust balance between precision and recall, underscoring robustness across different metrics. The strength of DenseNet121 lies in its densely connected convolutional layers, which promote efficient feature reuse and improve gradient flow across the network. This design minimizes the number of parameters while preserving high representational capacity, making the model more compact and efficient. The densely connected layers enable DenseNet121 to learn more robust features, a critical aspect in handling the complexity of visual data such as clothing images used for temperature classification. Consequently, the ability of model to maintain high precision and recall demonstrates its effectiveness in reducing both false positives and false negatives, key factors in achieving accurate classification results44. In contrast, ResNet101, which achieved an accuracy of 93.86%, struggled to match the performance of DenseNet121. While its sensitivity (93.34%) and specificity (94.39%) were relatively high, these values suggest some degree of overfitting, likely due to the deep architecture of network. While residual connections of ResNet101 are beneficial in mitigating the vanishing gradient problem, its deeper architecture of 101 layers can lead to overfitting, especially with datasets that are not sufficiently large or diverse. This overfitting issue may result in the model performing well on the training data but struggling to generalize effectively to new, unseen data, thus negatively affecting its precision and recall48. Similarly, ViT, with an accuracy of 93.13% and a sensitivity of 92.08%, fell short of DenseNet121, further illustrating the limitations of self-attention-based models in scenarios with more complex visual patterns like clothing images. ViT treats image patches as sequences similar to how tokens are used in natural language processing. Although ViT has shown promise in some domains, its effectiveness is often reliant on large datasets for training. In scenarios like this one, where the dataset size is relatively limited, CNN models like DenseNet121 tend to outperform ViT due to their ability to learn hierarchical and spatial features more effectively. The self-attention mechanism of ViT, while powerful for capturing long-range dependencies, may struggle to capture local spatial details critical for accurate image classification, such as distinguishing different temperature classes based on subtle variations in clothing49.

Both VGG16 and VGG19 performed well, particularly in terms of recall and F1-score, which can be attributed to their deep, sequential convolutional layers that facilitate extensive feature extraction. VGG19 achieved a recall of 96.21%, narrowly trailing DenseNet121, while VGG16 recorded a recall of 94.96%. However, these models also exhibited a tendency toward overfitting due to their high parameter count and depth, leading to a slight reduction in their overall accuracy compared to DenseNet12150. While, BiT demonstrating respectable performance with an accuracy of 92.33%, lagged behind the other models, particularly in precision (92.22%) and F1-score (92.52%). This may be attributed to reliance of BiT on transfer learning and the specific characteristics of the training dataset, which may not align optimally with the pre-trained model knowledge51.

Impact of semantic segmentation on air temperature classification performance

The implementation of semantic segmentation, particularly through the DeepLabV3 Plus architecture, has demonstrated a significant impact on the classification performance of models for air temperature classification using human clothing images. The results presented in Table 5 illustrate that all models trained on the segmented dataset achieved higher performance metrics compared to those trained on the non-segmented dataset (Table 6), with performance dropping by almost 50%. For instance, the accuracy of the DenseNet121 model on the segmented dataset reached 98.13%, while the same model only achieved 56.62% accuracy on the non-segmented dataset. Figure 10 shows the actual and predicted results generated by DenseNet121 on randomly sampled images from the segmented dataset, further illustrating the impact of segmentation. This stark contrast underscores the critical role that semantic segmentation plays in enhancing the ability of models to discern relevant features from the images, which is essential for accurate classification tasks52,53. The observed drop in performance metrics such as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1-Score, precision, recall, and AUC in the absence of segmentation can be attributed to inability of model to effectively isolate and identify the relevant features of clothing that correlate with varying air temperatures. Without semantic segmentation, the models are presented with cluttered images where the background and irrelevant details can obscure the critical features of clothing, leading to misclassification and reduced sensitivity to temperature related cues54. The segmentation process allows the models to focus on the pertinent regions of interest, thereby improving their ability to generalize and classify accurately. This is particularly important in the context of clothing images, where variations in color, texture, and layering can significantly influence temperature classification outcomes55.

Moreover, the DeepLabV3 Plus architecture employs atrous convolution, which enables the model to capture multi scale contextual information while maintaining spatial resolution. This capability is crucial for semantic segmentation tasks, as it allows the model to learn from a broader context of the image, enhancing its understanding of the relationships between different clothing items and their corresponding temperature classifications52,53. The ability to maintain high spatial resolution while capturing contextual information is a significant advantage that contributes to the superior performance metrics observed in the segmented dataset. In contrast, the non-segmented dataset lacks this refined feature extraction, resulting in a loss of critical information that is necessary for accurate classification54. The necessity of employing semantic segmentation, particularly through advanced architectures like DeepLabV3 Plus, is evident in the substantial improvements in classification performance for air temperature classification using human clothing images. The marked differences in performance metrics between the segmented and non-segmented datasets highlight the importance of isolating relevant features from complex images to enhance model accuracy and reliability. This approach not only improves classification outcomes but also provides a more robust framework for understanding the intricate relationships between clothing attributes and temperature classifications, ultimately leading to more effective applications in real world scenarios52,53.

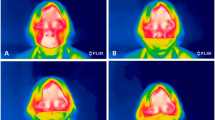

To further validate the deep transfer learning methods employed in this study, we applied Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) technique56 to visualize the essential pixels and area considered by the model in computation process for classification. The images are randomly selected from test set to perform this approach for all models. Figure 11 shows the resulting images with feature maps, where columns represent images (a) through (f), and rows represent different models. The first row presents the results generated by the BiT model, while the second row shows the results produced by ViT. In (a), (c), and (f) samples, BiT predictions are correct, while (b), (d), and (e) are incorrect predictions. ViT produced four correct predictions: (a), (b), (d), and (f), and two incorrect predictions: (c) and (e). ResNet produced four correct predictions: (a), (b), (d), and (e), and two wrong predictions: (c) and (f). VGG16 and VGG19 both produced five correct predictions. For VGG16, it corrected (a), (c), (d), (e), and (f), while (b) is incorrect. For VGG19, (a), (b), (c), (e), and (f) are correct, and (d) is incorrect. But DenseNet121 made accurate predictions for all six samples. Results show that, compared to other models, DenseNet121 exhibits a preference for broader scopes, integrating a greater amount of contextual feature data due to the depth of convolutional layers in architecture. Following DenseNet121, VGG16 and VGG19 took second place, while BiT, ViT, and ResNet101 demonstrated moderate performance.

Conclusion

Human attire images can represent the temperature levels induced by various weather phenomena. Deep learning is a powerful technique for detecting temperature levels using images. This paper presents a deep transfer learning framework for detecting temperature levels from mobile images. The framework consists of six different powerful deep learning models applied on HAID dataset for the classification task, including BigTransfer (BiT), Vision Transformer (ViT), ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and DenseNet121. DeepLabV3 Plus was also applied for semantic segmentation job. Furthermore, the Grad-CAM technique was performed to assess the classification performance and visualize the feature maps. The classification results, covering all metrics, demonstrate that DenseNet1121 outperformed other models in the classification of human attire images into high and low temperature classes. The developed system can be applied in weather phenomena recognition and environmental monitoring.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Cai, Z., Jiang, F., Chen, J., Jiang, Z. & Wang, X. Weather condition dominates regional PM2. 5 pollutions in the eastern coastal provinces of China during winter. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 18(4), 969–980 (2018).

Chatterjee, R., Chatterjee, A. & Islam, S. K. H. Deep learning techniques for observing the impact of the global warming from satellite images of water-bodies. Multimed. Tools Appl. 81(5), 6115–6130 (2022).

Yan, X., Luo, Y. & Zheng, X. Weather recognition based on images captured by vision system in vehicle. In Advances in Neural Networks–ISNN 2009: 6th International Symposium on Neural Networks, ISNN 2009 Wuhan, China, May 26–29, 2009 Proceedings, Part III 6 (ed. Yan, X.) 390–398 (Springer, 2009).

Lu, C., Lin, D., Jia, J., Tang, C.-K. Two-class weather classification. In: Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. pp. 3718–3725 (2014).

Lin, L. et al. A new visibility pre-warning system for the expressway. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 13, 67 (2005).

Tan, J., Gong, L. & Qin, X. Effect of imitation phenomenon on two-lane traffic safety in fog weather. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16(19), 3709 (2019).

Przybylska-Balcerek, A., Frankowski, J. & Stuper-Szablewska, K. The influence of weather conditions on bioactive compound content in sorghum grain. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 246, 13–22 (2020).

Xiao, H., Zhang, F., Shen, Z., Wu, K. & Zhang, J. Classification of weather phenomenon from images by using deep convolutional neural network. Earth Sp. Sci. 8(5), e2020EA001604 (2021).

Feng, H. & Zou, B. A greening world enhances the surface-air temperature difference. Sci. Total Environ. 658, 385–394 (2019).

Pachauri, R. K. et al., Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Ipcc, (2014).

Breitner, S. et al. Short-term effects of air temperature on mortality and effect modification by air pollution in three cities of Bavaria, Germany: A time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 485, 49–61 (2014).

Lan, L., Lian, Z. & Pan, L. The effects of air temperature on office workers’ well-being, workload and productivity-evaluated with subjective ratings. Appl. Ergon. 42(1), 29–36 (2010).

Schulte, P. A. et al. Advancing the framework for considering the effects of climate change on worker safety and health. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 13(11), 847–865 (2016).

Chung, J.-Y. et al. Ambient temperature and mortality: An international study in four capital cities of East Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 408(2), 390–396 (2009).

Ding-cheng, W., Chun-xiu, W., Yong-hua, X. & Tian-yi, Z. Air temperature prediction based on EMD and LS-SVM. In 2010 Fourth International Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computing (ed. Ding-cheng, W.) 177–180 (IEEE, 2010).

Ma, X., Fang, C., Ji, J. Prediction of outdoor air temperature and humidity using Xgboost. In: IOP conference series: earth and environmental science. IOP Publishing, 2020, p. 12013.

Yu, Z. et al. Dependence between urban morphology and outdoor air temperature: A tropical campus study using random forests algorithm. Sustain. Cities Soc. 61, 102200 (2020).

Guo, J. et al. Gluoncv and gluonnlp: Deep learning in computer vision and natural language processing. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 21(1), 845–851 (2020).

Liu, S., Li, M., Zhang, Z., Xiao, B. & Cao, X. Multimodal ground-based cloud classification using joint fusion convolutional neural network. Remote Sens. 10(6), 822 (2018).

Liu, S., Duan, L., Zhang, Z. & Cao, X. Hierarchical multimodal fusion for ground-based cloud classification in weather station networks. IEEE Access 7, 85688–85695 (2019).

Chen, Y., Kang, Y., Chen, Y. & Wang, Z. Probabilistic forecasting with temporal convolutional neural network. Neurocomputing 399, 491–501 (2020).

Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. In: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. pp. 1440–1448 (2015).

Parkhi, O., Vedaldi, A., Zisserman, A. Deep face recognition. In: BMVC 2015-Proceedings of the British Machine Vision Conference 2015. (British Machine Vision Association, 2015).

Guo, X., Chen, Y., Liu, X. & Zhao, Y. Extraction of snow cover from high-resolution remote sensing imagery using deep learning on a small dataset. Remote Sens. Lett. 11(1), 66–75 (2020).

Lu, J. et al. P_SegNet and NP_SegNet: New neural network architectures for cloud recognition of remote sensing images. IEEE Access 7, 87323–87333 (2019).

Dev, S., Nautiyal, A., Lee, Y. H. & Winkler, S. CloudSegNet: A deep network for nychthemeron cloud image segmentation. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 16(12), 1814–1818 (2019).

Guerra, J. C. V., Khanam, Z., Ehsan, S., Stolkin, R. & McDonald-Maier, K. Weather Classification: A new multi-class dataset, data augmentation approach and comprehensive evaluations of Convolutional Neural Networks. In 2018 NASA/ESA Conference on Adaptive Hardware and Systems (AHS) (ed. Guerra, J. C. V.) 305–310 (IEEE, 2018).

Wang, Y. & Li, Y. Research on multi-class weather classification algorithm based on multi-model fusion. In 2020 IEEE 4th Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC) (ed. Wang, Y.) 2251–2255 (IEEE, 2020).

Wang, C., Liu, P., Jia, K., Jia, X. & Li, Y. Identification of weather phenomena based on lightweight convolutional neural networks. Comput. Mater. Contin. 64(3), 2043–2055 (2020).

Tan, L., Xuan, D., Xia, J. & Wang, C. Weather recognition based on 3C-CNN. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 14(8), 3567–3582 (2020).

Zhao, B., Li, X., Lu, X. & Wang, Z. A CNN–RNN architecture for multi-label weather recognition. Neurocomputing 322, 47–57 (2018).

Zhao, W., Chow, D., Yan, H. & Sharples, S. Influential factors and predictive models of indoor clothing insulation of rural residents: A case study in China’s cold climate zone. Build. Environ. 216, 109014 (2022).

de Carvalho, P. M., da Silva, M. G. & Ramos, J. E. Influence of weather and indoor climate on clothing of occupants in naturally ventilated school buildings. Build. Environ. 59, 38–46 (2013).

Tamura, T. Clothing as a mobile environment for human beings prospects of clothing for the future. J. Hum.-Environ. Syst. 10(1), 1–6 (2007).

Chen, L.-C., Papandreou, G., Kokkinos, I., Murphy, K., Yuille, A. L. Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets and fully connected crfs. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/quant-ph/1412.7062 (2014).

Chen, L.-C., Papandreou, G., Kokkinos, I., Murphy, K. & Yuille, A. L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40(4), 834–848 (2017).

Chen, L.-C., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F., Adam, H. Rethinking atrous convolution for semantic image segmentation. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/quant-ph/1706.05587 (2017).

Chen, L.-C., Zhu, Y., Papandreou, G., Schroff, F., Adam, H. Encoder-decoder with atrous separable convolution for semantic image segmentation. In: Proc. European conference on computer vision (ECCV). pp. 801–818 (2018).

Kolesnikov, A. et al. Big transfer (bit): General visual representation learning. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part V 16 (ed. Kolesnikov, A.) 491–507 (Springer, 2020).

Wu, Y., He, K. Group normalization. In: Proc. European conference on computer vision (ECCV). pp. 3–19 (2018).

Qiao, S., Wang, H., Liu, C., Shen, W., Yuille, A. Micro-batch training with batch-channel normalization and weight standardization. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/quant-ph/1903.10520 (2019).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. pp. 770–778 (2016).

J. Devlin, M.-W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova, Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/quant-ph/1810.04805 (2018).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L., Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. pp. 4700–4708 (2017).

Simonyan, K., Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Preprint at https://arXiv.org/quant-ph/1409.1556 (2014).

Holloway, R. ROC analysis in theory and practice. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 6(3), 343–351 (2017).

Visa, S., Ramsay, B., Ralescu, A. L. & Van Der Knaap, E. Confusion matrix-based feature selection. Maics 710(1), 120–127 (2011).

Zheng, Y. & Jiang, W. Evaluation of vision transformers for traffic sign classification. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3041117 (2022).

Nikitin, V. & Danylov, V. Integration of fractal dimension in vision transformer for skin cancer classification. Electron. Control Syst. 2(76), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.18372/1990-5548.76.17662 (2023).

Naseer, M. et al. Intriguing properties of vision transformers. ArXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2105.10497 (2021).

Wang, X. & Guo, P. Domain adaptation via bidirectional cross-attention transformer. ArXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2201.05887 (2022).

Chen, L.-C., Papandreou, G., Kokkinos, I., Murphy, K. & Yuille, A. DeepLab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, Atrous convolution, and fully connected CRFs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 40(4), 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpami.2017.2699184 (2018).

Geng, Q., Zhou, Z. & Cao, X. Survey of recent progress in semantic image segmentation with CNNs. Sci. China Inf. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11432-017-9189-6 (2017).

Wang, Z., Guo, J., Huang, W. & Zhang, S. High-resolution remote sensing image semantic segmentation based on a deep feature aggregation network. Meas. Sci. Technol. 32(9), 95002. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6501/abfbfd (2021).

ChannappaGowda, D. V. & Kanagavalli, R. Video semantic segmentation network with low latency based on deep learning. Int. J. Commun. Networks Inf. Secur. 15(3), 209–225. https://doi.org/10.17762/ijcnis.v15i3.6266 (2023).

R. R. Selvaraju, M. Cogswell, A. Das, R. Vedantam, D. Parikh, and D. Batra, “Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. In: Proc. IEEE international conference on computer vision. pp. 618–626 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that, this article has been produced with the financial support of the European Union under the REFRESH – Research Excellence for Region Sustainability and High-tech Industries project number CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048 via the Operational Programme Just Transition, project TN02000025 National Centre for Energy II and ExPEDite project a Research and Innovation action to support the implementation of the Climate Neutral and Smart Cities Mission project. ExPEDite receives funding from the European Union’s Horizon Mission Programme under grant agreement No. 101139527 and The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through the project number (TU-DSPP-2024-70).

Funding

This research was funded by Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia (TU-DSPP-2024-70).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Maqsood Ahmed., conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, software, visualization, writing—original draft; Xiang Zhang., investigation, project administration, supervision, writing—review and editing; Yonglin Shen., resources, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing; Nafees Ali., data curation, methodology, software, writing—review and editing; Aymen Flah., formal analysis, funding acquisition, software, writing—review and editing; Mohammad Kanan., data curation, methodology, visualization, writing—review and editing; Mohammad Alsharef., data curation, methodology, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, grammar checking; Sherif S. M. Ghoneim., data curation, funding acquisition, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study involved the analysis of images of human clothing for air temperature classification. No experiments were conducted on human subjects or tissues, and therefore, ethical approval from an institutional or licensing committee was not required.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants for the use of their images in this publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, M., Zhang, X., Shen, Y. et al. A deep transfer learning based convolution neural network framework for air temperature classification using human clothing images. Sci Rep 14, 31658 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80657-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80657-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Deep transfer learning framework for thermal tomographic image classification: a comparative study

Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design (2026)