Abstract

Severe community-acquired pneumonia (SCAP) is a serious respiratory inflammation disease with high morbidity and mortality. This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic value of the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), basophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (BLR) and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (ELR) in patients with SCAP. The study retrospectively included 554 patients with SCAP, and the clinical data were obtained from the electronic patient record (EMR) system. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality, and the secondary outcomes included hospital length of stay (LOS), overall survival (OS), admission to ICU, ICU LOS, and ICU mortality. The results showed that both NLR and BLR were significant but not independent prognostic factors for in-hospital mortality; NLR was negatively correlated with hospital LOS while ELR was positively correlated with hospital LOS; both increased NLR and increased BLR were associated with reduced OS, while increased ELR was associated with improved OS; increased PLR, NLR, MLR, and BLR were all correlated with elevated ICU admission rates, while increased ELR was correlated with a reduced ICU admission rate; ELR was positively correlated with ICU LOS; both higher NLR and higher BLR were associated with increased ICU mortality. In summary, NLR and BLR were useful prognostic factors for clinical outcomes in patients with SCAP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is one of the leading causes of hospitalization, morbidity, and mortality worldwide, and the in-hospital mortality rates range from 17 to 49% in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia (SCAP) in accordance with large multicenter cohort studies1. A recent Chinese retrospective study involving 3786 patients with SCAP revealed an in-hospital mortality rate of 32.4%2.

In recent years, increasing studies found that systemic inflammatory factors including the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR) served as prognostic factors in respiratory disease, such as acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD)3, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)4, pulmonary fibrosis5, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)6,7. For instance, elevated PLR, NLR, and MLR were all associated with increased hospital length of stay (LOS) and in-hospital mortality as well as exacerbated airflow limitation in AECOPD3; increased PLR, NLR, and MLR were poor prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) in patients with curatively resected NSCLC4. In addition, PLR, NLR, and MLR are used to predict the severity of COVID-19; NLR and MLR have predictive value for mortality in COVID-196,7.

With respect to the prognostic roles of PLR, NLR, and MLR in SCAP, a recent Chinese retrospective study found that raised NLR was associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP and type 2 diabetes mellitus2. In addition, both PLR and NLR were independent predictive factors for poor prognosis in paediatric severe pneumonia8. However, the prognostic roles of PLR, NLR, and MLR in SCAP are still poorly understood.

The basophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (BLR) and eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (ELR) are reliable indicators of systemic inflammation9,10,11. Unlike PLR, NLR, and MLR, increased ELR was correlated with reduced hospital LOS and in-hospital mortality in AECOPD3. Increased BLR is a poor prognostic factor for clinical outcomes in metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer and NSCLC12,13.

The present study aimed to investigate the prognostic value of systemic inflammatory factors including PLR, NLR, MLR, BLR, and ELR in patients with SCAP.

Methods

Patients

The retrospective study was carried out in the Sichuan Academy of Medical Science and Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital, Chengdu, China. Patients with SCAP admitted to the hospital between 25 August, 2018 and 28 December, 2021 were included into the study. Due to the retrospective and non-interventional design, written informed consent could be waved in light of relevant Chinese guidelines and laws. The waver and study protocol were approved by the independent Medical Ethics Committee of Sichuan Academy of Medical Science and Sichuan Provincial People’s Hospital (No. Lunshen-Yan-2023-number-398). Additionally, 300 healthy volunteers from the Department of Laboratory Medicine of People’s hospital of Guilin were also retrospectively included into this study (Supplementary Table S1). It was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of People’s hospital of Guilin (No. 2022-011KY), and written informed consent was also waved. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

SCAP was diagnosed on the basis of 1 major criterion or ≥ 3 minor criteria proposed by the Joint Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and American Thoracic Society (ATS)14. Patients diagnosed with SCAP admitted to the hospital were included, and SCAP should be the direct cause of death if in-hospital mortality occurred. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) under 18 years old; (2) patients with seriously missing clinical data; (3) human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, autoimmune diseases, severe immunosuppression or immunosuppressive therapy; (4) critically ill without completed treatment (e.g. abandoning therapy), and the status of survival after discharge from hospital was unknown; (4) end-stage diseases, or acute events such as acute heart failure and acute myocardial infarction, which were fatal to the patients.

In the hospital, each patient with SCAP had a diagnosis on admission and a diagnosis on discharge, and we retrospectively identified pneumonia patients according to the two diagnoses. The diagnosis on admission was a preliminary diagnosis, and the diagnosis on discharge was a confirmed diagnosis. CAP and hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) were differentiated according to the diagnosis on admission, diagnosis on discharge, and treatment process. In addition, the diagnosis code lists used in the hospital were ICD-10 and ICD-9 for internal medicine and surgery, respectively.

Data collection

The clinical data of the patients were acquired using the electronic medical record (EMR) system. The demographic data consisted of age and gender. The comorbidities of the patients with SCAP were recorded, and included cancer, hematological disease, hepatic disease, renal disease, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular disease. Hepatic disease was identified through EMRs, paper medical records (PMRs), and liver function tests.

Patients admitted with SCAP underwent a comprehensive series of physical examinations and laboratory assessments, including vital sign monitoring, microbiological analysis, complete blood count (CBC), and liver function tests (LFTs). Patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia were excluded from the study, as these cases were referred to specialized departments or hospitals for quarantine and treatment15.

The vital signs comprised temperature, respiratory rates, heart rates, systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). CBC, also known as the blood routine test, referred to the counts of the white blood cell (WBC), neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocyte, eosinophil, basophil, platelet, and red blood cell (RBC). The other laboratory examinations involved myoglobin, high-sensitivity troponin (Hs-Tn), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine (Scr), glucose, uric acid (UA), serum potassium, albumin, globulin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total bilirubin (TBIL), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), prothrombin time (PT), D-dimers, procalcitonin, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). In addition, arterial blood gas analysis (BGA) was performed at diagnosis in the patients, and the primary parameters were pH, PaO2 (arterial oxygen tension), and arterial carbon dioxide tension (PaCO2). Only the first admission was recorded for patients who had multiple admissions.

For the healthy volunteers, the clinical data were derived from regular medical examinations, and were collected from the EMRs of the Department of Laboratory Medicine of People’s hospital of Guilin. The clinical parameters consisted of age, gender, and CBC.

Clinical outcome

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality, and the secondary outcomes were hospital LOS, OS, and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). For the patients admitted to ICU, ICU LOS and ICU mortality were recorded. If patients with SCAP died during hospitalization, LOS was calculated from the date of admission to the hospital to the date of death. For patients with SCAP died during ICU treatment, ICU LOS was calculated using the same way. OS was calculated from the date of the diagnosis of SCAP to the date of death.

Initial antimicrobial treatment

Following the diagnosis of SCAP, patients received initial antimicrobial therapy, primarily administered as empiric treatment. Antimicrobial therapy was classified as inappropriate if the identified etiological agents were not covered within the antimicrobial spectrum of the administered agents1,14,16,17,18,19,20,21. Additionally, patients with SCAP were provided with mechanical ventilation, high-flow nasal oxygen, and symptomatic treatments, including antipyretics, expectorants, and anti-inflammatory agents1,16,17,18,22,23. Upon completing a treatment course, clinicians evaluated each patient’s physical condition. Patients demonstrating recovery, no longer requiring hospitalization, were recommended for discharge. In cases of treatment failure, clinicians considered adjustments to the antimicrobial regimen or referral to a higher-level facility for advanced care. Patients were followed up until discharge from the referred hospital or until death. For patients discharged in recovery, overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of SCAP diagnosis to the date of hospital discharge (censoring date).

Statistical analysis

The normal distribution of continuous data was determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For continuous clinical data with an abnormal distribution, the clinical data are described as medians (interquartile range, IQR), the comparison between independent groups was performed by Mann-Whitney U test24, and the comparison between paired samples was performed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test25. In addition, the correlation between the continuous clinical data was determined using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Categorical variables were compared between two groups using the Chi Square test or Fisher’s exact test.

The association of clinical characteristics with dichotomous outcomes in patients with SCAP was determined using binary logistic regression analysis along with the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Multcollinearity diagnosis was performed to determine the linear intercorrelation between systemic inflammatory factors and other clinical factors associated with in-hospital mortality in SCAP26. The variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance were two diagnostic tools used to determine the presence of multcollinearity (sometimes termed collinearity), and the product of the two values of VIF and tolerance is equal to 127,28. Therefore, only VIF was used to evaluate the multcollinearity in the present study. The value of VIF = 1 indicated the absence of multcollinearity between systemic inflammatory factors and other clinical factors associated with in-hospital mortality in SCAP, and higher VIF values indicated stronger multcollinearity26,28,29. A value of VIF > 10 indicated a high degree of multcollinearity necessitating processing the data for systemic inflammatory factors or the other clinical factors, otherwise it would result in misleading statistical results27,29,30.

A survival curve was plotted using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the difference between two groups was determined by the log-rank test. The univariate analysis of systemic inflammatory factors associated with OS was performed using Cox regression, and the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% CI were calculated by a Cox proportional hazards model. In addition, no imputation method was used to process missing clinical data in the above statistical analyses.

A nomogram for predicting in-hospital mortality was established on the basis of the results of the binary logistic regression analysis. R (version 4.0.0) analysis packages, including rms version 6.3-0 and rmda version 1.6, were used to plot the nomogram and perform the validation31. The multiple imputation method was used to process missing data for the nomogram, and all the missing values for continuous clinical data were replaced with the corresponding imputation values32. The precondition was that the missing values accounted less than 20%, otherwise the variable would be excluded.

The prognostic ability of the nomogram for in-hospital mortality in SCAP was indicated by the area under the curve (AUC) of a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and the comparison of AUCs was performed by Delong test33.

All of the statistical analyses and multiple imputation were performed using SPSS software version 26.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of 554 patients with SCAP

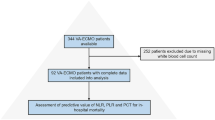

A total of 833 patients with severe pneumonia were preliminarily included into the retrospective study using the EMR system, and 554 eligible patients with SCAP were included into the analysis based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients with SCAP are described in Table 1. A total of 141 in-hospital deaths occurred among the eligible patients with SCAP, and the in-hospital mortality rate was 25.5%. The patients with SCAP were divided into the dead group and survival group based on whether in-hospital death occurred.

The patients with SCAP consisted of 383 male patients (69.1%) and 171 female patients (30.9%), with a median age of 71 years old. The common clinical symptoms of SCAP were fever (50.7%), cough (75.3%), expectoration (67.0%), dyspnea (24.2%), disorientation (19.7%), and coma (11.4%). 234 (42.2%) patients with SCAP were accompanied by hypertension, and 112 (20.2%) patients with SCAP were accompanied by diabetes mellitus. Among the patients with SCAP and diabetes mellitus, 109 patients (97.3%) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus. 276 (49.8%) and 59 (10.6%) patients with SCAP were infected with bacteria and fungi, respectively. 49 (8.8%) patients with SCAP were coinfected with bacteria and fungi. 12 (2.2%) patients with SCAP were infected with viruses, mycoplasmas, or mixed etiological agents. In addition, 158 (28.5%) patients did not undergo tests for etiological agents, or had a failed test for etiological agents. With respect to initial antimicrobial treatments, 477 (86.1%) patients with SCAP received antibacterial agents; 73 (13.2%) patients with SCAP received antibacterial agents plus antifungal agents; and only 4 (0.7%) patients with SCAP received antifungal agents. The initial antimicrobial treatments were primarily based on empiricism, and 50 (12.6%) patients were found to receive inappropriate antimicrobial treatments according to the test results of etiological agents (Table 1).

The vital signs and laboratory examinations are also summarized in Table 1. The median PLR, NLR, MLR, BLR, and ELR were 236.7, 11.91, 0.581, 0.028, and 0.021, respectively. A total of 554 blood samples for blood routine tests were collected from the 554 patients with SCAP, 463 blood samples (83.6%) were collected on the day of admission, and 72 blood samples (13.0%) were collected on the second day of hospitalization. Only 19 blood samples (3.4%) for blood routine tests were collected on the third day of hospitalization.

As shown in Table 1, age, respiratory rates, base excess (BE), PT, and the levels of WBC, neutrophils, NLR, BLR, myoglobin, BUN, Scr, glucose, UA, serum potassium, AST, LDH, D-dimers, procalcitonin, and hs-CRP were significantly higher in the dead group compared with the survival group (all P < 0.05). On the contrary, SBP, DBP, pH, and the levels of RBC, hemoglobin, and albumin were significantly lower in the dead group compared with the survival group (all P < 0.05). In addition, the dead group had marginally increased heart rates (P = 0.056) and BNP (P = 0.084) as well as marginally decreased platelets (P = 0.054) compared to the survival group.

The incidences of both disorientation and coma were significantly higher in the dead group compared to the survival group (both P < 0.05). The comorbidities including cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus as well as the number of comorbidities were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (all P < 0.05).

Correlations of clinical characteristics with in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP

The age, respiratory rate, pH, BE, WBC, neutrophil, NLR, BLR, myoglobin, BUN, Scr, glucose, UA, serum potassium, AST, LDH, PT, D-dimer, procalcitonin, hs-CRP, SBP, DBP, RBC, hemoglobin, albumin, disorientation, coma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, number of comorbidities, heart rate, BNP, and platelet had significant or marginal associations with in-hospital mortality in the patients with SCAP, and were included into binary logistic regression analysis to evaluate their prognostic value for in-hospital mortality. As shown in Table 2, the age, respiratory rate, heart rate, disorientation, coma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, number of comorbidities, BE, WBC, NLR, BLR, myoglobin, BUN, UA, AST, LDH, PT, D-dimer, and hs-CRP were significant risk factors for in-hospital mortality (all OR > 1, P < 0.05). Increased SBP, DBP, pH, RBC, hemoglobin, and albumin were significantly correlated with reduced in-hospital mortality (all OR < 1, P < 0.05). A raised platelet level was marginally related to reduced in-hospital mortality (OR < 1, P = 0.064), while the increased levels of both glucose (OR > 1, P = 0.062) and procalcitonin (OR > 1, P = 0.076) were marginally related to increased in-hospital mortality.

Thus, the age, respiratory rate, heart rate, disorientation, coma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, number of comorbidities, pH, BE, WBC, NLR, BLR, myoglobin, BUN, UA, AST, LDH, PT, D-dimer, hs-CRP, SBP, DBP, RBC, hemoglobin, and albumin as significant prognostic factors were included into multivariate binary logistic regression analysis to screen independent prognostic factors for in-hospital mortality in the patients with SCAP (Table 3). The results showed that the age, respiratory rate, heart rate, DBP, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and RBC were significant independent prognostic factors for in-hospital mortality (all P < 0.05). Neither NLR nor BLR was a significant independent prognostic factor for in-hospital mortality, due to the potential collinearity between NLR/BLR and the other clinical factors associated with in-hospital mortality. Therefore, multicollinearity diagnosis was performed to identify the prognostic factors that were highly correlated with NLR or BLR (Table 4). Herein, NLR and BLR still served as categorical variables. The results showed that all of the VIF values were much less than 10, indicating a low degree of multicollinearity between NLR/BLR and the other clinical factors associated with in-hospital mortality in SCAP.

Establishment and validation of a predictive model

The age, respiratory rate, heart rate, DBP, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and RBC were used to establish a nomogram to predict in-hospital mortality in the patients with SCAP. Moreover, BLR and PT were also incorporated into the nomogram in view of the P values for BLR (P = 0.077) and PT (P = 0.054) close to 0.05 in the multivariate binary logistic regression analysis. Each prognostic factor designated a score presented on the top line of the nomogram. A summation of the scores for all prognostic factors was obtained, the total score reflected a score presented on the bottom line of the nomogram, and it denoted the probability of in-hospital mortality in a patient with SCAP (Fig. 2). The nomogram had good prognostic value for in-hospital mortality, with an index of concordance (C-index) of 0.758 (95% CI 0.714–0.801). A calibration curve and decision curve analysis (DCA) were used to evaluate the clinical applicability of the nomogram34. The calibration curve was plotted through bootstrap sampling 2000 times, and it showed that the predicted values by the nomogram were generally in line with the actually observed values (Fig. 3A). The DAC curve indicated that the nomogram had good net benefits in a range of 0.2–0.5 of threshold probabilities, demonstrating the good clinical applicability of the nomogram (Fig. 3B).

The calibration curve and decision curve analysis (DCA) of the nomogram. (A) In the calibration curve, perfect prediction corresponded to the “ideal” line, the “Apparent” line represented the entire cohort (n = 554), and the “Bias-corrected” line was plotted through bootstrapping (B = 2000 repetitions), indicating observed nomogram performance. (B) In DCA, the horizontal black line and gray oblique line refer to no patient with SCAP and all patients with SCAP, respectively. SCAP severe community-acquired pneumonia.

CURB-65, as a prognostic rule developed in 2003, is computed using confusion, blood urea nitrogen > 7 mmol/l, respiratory rates > 30/min, and low blood pressure (SBP < 90 mmHg or DBP < 60 mmHg)35. CURB-65 is used to evaluate the severity and predict clinical outcomes in patients with CAP, and it can also be used to predict the prognosis in patients with SCAP35,36,37. The total difference in in-hospital mortality among CURB-65 scores was determined by Chi Square test, and the association of CURB-65 scores and in-hospital mortality was evaluated using binary logistic regression analysis. As a result, in-hospital mortality increased with the increase of CURB-65, and a significant difference in in-hospital mortality was observed among CURB-65 scores (χ2 = 56.235, P < 0.001). CURB-65 was a significant prognostic factor for in-hospital mortality in SCAP (Table 5). The prognostic abilities of the nomogram and CURB-65 for in-hospital mortality in SCAP were compared, and the AUC of a ROC curve was used to evaluate the predictive ability. The AUC values for the nomogram and CURB-65 were 0.758 and 0.692, respectively (Fig. 4), and the nomogram had significantly higher AUC than CURB-65 (P = 0.047), indicating the nomogram had higher predictive value for in-hospital mortality in SCAP compared to CURB-65.

Associations of systemic inflammatory factors with hospital length of stay (LOS) and overall survival (OS)

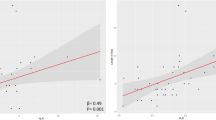

The median (25th–75th centile) hospital LOS was 12 (6–19) days, and the correlations of systemic inflammatory factors with hospital LOS were determined using Spearman correlation coefficients. As shown in Fig. 5A, NLR was negatively correlated with hospital LOS (r = −0.109, P = 0.010) while ELR was positively correlated with hospital LOS (r = 0.154, P < 0.001). In order to eliminate the survivor bias, the correlations of systemic inflammatory factors with hospital LOS were analyzed in the survival patients in hospital (n = 413). As a result, NLR still had a negative correlation with hospital LOS (r = −0.106, P = 0.032) while ELR had a positive correlation with hospital LOS (r = 0.114, P = 0.020, Fig. 5B).

The association of systemic inflammatory factors with OS was determined using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the values of systemic inflammatory factors were cut-off by the corresponding median values. As shown in Fig. 5C; Table 6, both higher NLR and higher BLR were associated with worse OS (both P < 0.05), while higher ELR was associated with better OS (P = 0.013).

Associations of systemic inflammatory factors with hospital LOS and OS in patient with SCAP. (A) Associations of NLR, BLR, and ELR with hospital LOS in patient with SCAP. (B) Associations of NLR, BLR, and ELR with hospital LOS in survival patients with SCAP in hospital. (C) Associations of NLR, BLR, and ELR with OS in patient with SCAP. SCAP severe community-acquired pneumonia, LOS length of stay, OS overall survival, NLR neutrophil-to-lymphocyte, BLR basophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, ELR eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Associations of systemic inflammatory factors with ICU admission, length of stay (LOS), and mortality

Among the included patients with SCAP, 386 patients (69.7%) were admitted into ICU based on critical conditions. The values of systemic inflammatory factors were cut-off by the corresponding median values, and the relationships between systemic inflammatory factors and ICU admission were analyzed using the chi-square test. As shown in Table 7, increased PLR, NLR, MLR, and BLR were all correlated with elevated ICU admission rates (all P < 0.05), while increased ELR was correlated with a reduced ICU admission rate (P = 0.016).

In the 386 patients admitted into ICU, 114 patients (29.6%) died during ICU therapy, and the corresponding median (25th–75th percentile) PLR, NLR, MLR, BLR, and ELR were 243.2 (135.6–479.9), 14.72 (7.28–25.88), 0.639 (0.357–1.023), 0.032 (0.015–0.057), and 0.017 (0.000–0.091), respectively. The median (25th–75th centile) ICU LOS was 9 (4–15) days. The correlations of systemic inflammatory factors with ICU LOS was determined by Spearman correlation coefficients. As shown in Fig. 6, ELR was positively correlated with ICU LOS (r = 0.153, P = 0.003), whereas PLR, NLR, MLR, or BLR had no significant correlation with ICU LOS (all P > 0.05). Both higher NLR and higher BLR were associated with increased ICU mortality (both P < 0.05, Table 8).

The levels of systemic inflammatory factors in patients with SCAP and healthy volunteers

Age, gender, CBC, hemoglobin, systemic inflammatory factors were compared between the patients with SCAP and healthy volunteers. The comparison of gender ratios was performed using the chi-square test, and the other comparisons were performed by Mann–Whitney U test based on the abnormal distribution of the clinical data. As shown in Table 9, the patients with SCAP had significantly older age and higher male-female ratios than the healthy volunteers (both P < 0.05). PLR, NLR, MLR, and BLR were substantially elevated in the patients with SCAP compared with the healthy volunteers, meanwhile ELR was markedly decreased (all P < 0.001).

413 of 554 (74.4%) patients with SCAP met the condition of hospital discharge after therapy and were discharged from the hospital. In these patients, blood gas analyses were performed in 214 patients (51.8%), and blood routine examinations were performed in 253 patients (61.3%). The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to perform the paired comparison of the clinical characteristics at admission and discharge in the patients with SCAP based on the abnormal distribution of the difference values. As shown in Table 10, both PaCO2 and PaO2 were significantly improved at discharge compared to hospital admission (both P < 0.05). PLR, NLR, and MLR were lowered whereas ELR was improved at discharge compared to hospital admission (all P < 0.05).

Taken together, PLR, NLR, and MLR were improved in patients with SCAP compared to healthy volunteers, and were reduced when the patients were in recovery after treatment. Meanwhile, ELR exhibited a complete opposite trend. In addition, BLR was also elevated in patients with SCAP compared with healthy volunteers.

Discussion

To our best knowledge, this was the first study to evaluate the prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory factors (PLR, NLR, MLR, BLR, and ELR) in patients with SCAP. BLR is a rarely studied disease biomarker, a recent study aimed to investigate the associations of systemic inflammatory factors (PLR, NLR, MLR, BLR, and ELR) with clinical outcomes in patients with AECOPD, and the results revealed that only BLR had no association with the clinical outcomes involving hospital LOS, airflow limitation, and in-hospital mortality3. Nevertheless, our study found that BLR served as an important biomarker in SCAP, and elevated BLR was associated with increased in-hospital mortality, ICU admission rates, and ICU mortality in patients with SCAP. Moreover, higher BLR was correlated with worse OS, and BLR was elevated in patients with SCAP compared to healthy volunteers. Basophils, as the least abundant granulocytes, are often neglected due to the extremely low proportion in granulocytes. Basophils belong to white blood cells, and are the minority in the immune system38. However, increasing studies found that basophils played a key role in immunity, especially T helper type 2 immunity and allergic inflammation39,40,41. Basophils and mast cells are closely linked in function, and have some similar phenotypes39. The marked difference between them are that basophils mature in the bone marrow with a lifespan of 2–3 days42. Basophils can drive the pro-inflammatory response through recruitment of effector cells including eosinophils to inflammatory sites40,42,43.

Previous studies have found that acute cardiac events were frequent and were associated with mortality in CAP/SCAP44,45,46,47,48,49. The inflammatory response plays a crucial role in the development of acute cardiac events. It can induce acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or acute lung injury (ALI), and evolves into systemic inflammatory response, resulting in endothelial dysfunction and pro-coagulant conditions49. Consequently, it remarkably raises the risk of acute cardiac events, such as acute myocardial infarction47,49. It has been reported that systemic inflammatory factors (e.g. PLR and NLR) could be used to predict acute cardiac events in various diseases50,51,52,53. However, our study aimed to investigate the direct associations of PLR, NLR, MLR, BLR, and ELR with in-hospital mortality in SCAP. Therefore, the SCAP patients with acute cardiac events, such as acute heart failure and acute myocardial infarction, were excluded.

A systematic review has revealed that NLR > 10 was associated with higher mortality in patients with CAP, and NLR was a promising predictor comparable to common predictors including CRP, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, a pneumonia severity index (PSI), procalcitonin, and CURB-6554. Our study further demonstrated that NLR ≥ 11.91 was associated with higher in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP. Noteworthily, SCAP as a severe form of CAP has similar pathogens, etiology, risk factors, and treatment to CAP22,23,55,56,57,58,59. Interestingly, NLR was also used to predict the severity of CAP and distinguish SCAP and non-severe CAP60,61. Neutrophils and lymphocytes are the main mediators of inflammation62. Neutrophils and lymphocytes play key roles in the innate immune system and adaptive immune system, respectively63,64. Neutrophils serve as a marker of acute inflammatory response, while lymphocytes substantially contribute to inducing the chronic inflammatory response, and NLR reflects the equilibrium between neutrophils (inflammatory regulator) and lymphocytes (inflammatory activator)62,63. NLR is an accessible indicator of cellular immune reflecting the stress and systemic inflammatory response, and is used to predict the severity and outcomes in various diseases64.

Unlike PLR, NLR, and MLR, elevated ELR was identified to be a favourable prognostic factor in AECOPD. Namely, elevated ELR was associated with better clinical outcomes, including reduced hospital LOS, in-hospital mortality, and alleviated airflow limitation3. In this study, increased ELR was associated with improved OS and reduced ICU admission rates, and ELR was positively correlated with hospital LOS as well as ICU LOS. Moreover, ELR were lowered in patients with SCAP compared to healthy volunteers, and improved when the patients were in recovery after treatment. Taken together, higher ELR was correlated with better prognosis and longer LOS in the hospital and ICU for patients with SCAP.

Elevated ELR seemed to play a protective role in SCAP, and it could attribute to the effect of increased eosinophils, because ELR exhibited the opposite trend to BLR as well as NLR in SCAP. Eosinophils are granulocytes derived from bone marrow, and belong to WBCs. Eosinophils only account for 1–3% of WBCs in peripheral blood, but are involved in various biological processes65,66. Eosinophils can produce, stockpile and release growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines67. Among them, cytokines and chemokines were involved in the inflammatory response, and guide eosinophils to expand and infiltrate inflamed tissue, whereby conserving the lung architecture66,68. Eosinophils exert homeostatic effects on immune responses, and are implicated in defensing against a wide range of infections caused by parasites, bacteria, and viruses through interaction with T cells65,68. Eosinophils can be used to monitor or predict disease development, activity, and severity as well as therapeutic response in several lower airway diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and allergic asthma69,70. Previous studies have revealed that a lower eosinophil level was related to more severe bacterial infection71,72,73. In AECOPD, an increased eosinophil level was associated with reduced mortality, shortened hospital LOS, and an elevated readmission rate74.

It has been reported that increased NLR was associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and NLR was an independent prognostic factor for hospital and ICU mortality in renal transplant recipients with SCAP2,75. Additionally, NLR was related to the disease severity and 90-day mortality in patients with CAP, and was an independent prognostic factor for discharge or death/progression of CAP75,76,77,78. In this study, increased NLR was a significant but not independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality. Moreover, NLR was negatively correlated with hospital LOS; raised NLR was associated with reduced OS, elevated ICU admission rates, and increased ICU mortality. NLR was improved in patients with SCAP compared to healthy volunteers, and was reduced when the patients were in recovery after treatment. Taken together, higher NLR was associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with SCAP.

In the current study, diabetes mellitus was a risk factor for in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP. In the patients with SCAP accompanied by diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes mellitus in the main type of diabetes mellitus, and accounted for 97.3%. Evidently, type 2 diabetes mellitus was also a risk factor for in-hospital mortality. This finding was consistent with the results of the retrospective study performed by Huang D, et al.2. In addition, increased blood glucose was marginally associated with increased in-hospital (P = 0.062, Table 2), and these results were mutually corroborative.

This study found that hypertension was a risk factor for in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP. However, both elevated SBP and elevated DBP were correlated with reduced in-hospital mortality (Table 2), and these results seemed contradictory. In accordance with the International Society of Hypertension (ISH) guideline, hypertension is defined as SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg measured in clinics19. In the present study, hypertension was recorded into the EMR system based on a patient’ medical history instead of blood pressure measurement. Importantly, the SBP and DBP referred to the results of blood pressure measurement at admission. We found that some patients with hypertension did not meet the diagnostic criteria of hypertension on condition that SBP and DBP at admission were applied. In fact, SBP and DBP at admission were affected by many clinical factors, including physical condition and medications. Under the condition of SCAP, SBP and DBP were likely to fluctuate. To sum up, our findings were not contradictory, and could be explained.

Previous studies found that liver cirrhosis and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) were associated with increased mortality in patients with CAP79,80,81. In the present study, elevated AST was associated with increased in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP, this result was consistent with the finding of another Chinese retrospective study involving 3786 patients with SCAP2. However, no significant association between hepatic disease and in-hospital mortality of patients with SCAP was found in the current study. In fact, hepatic diseases involve all diseases occurring in the liver, including hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatitis, NAFLD, liver cirrhosis, etc. An important characteristic of hepatic diseases was subtle symptoms, leading to the difficulty of identifying the presence of hepatic disease, especially in the early and middle phases of hepatic disease. Thus, the identification and diagnosis of hepatic disease primarily depend on various medical examinations82,83,84. In critically ill patients, hepatic dysfunction is often neglected, due to its subtle occurrence and less likelihood of being lethal compared to cardiovascular, renal, or respiratory failure85. In the present study, the primary diagnosis of the patients was SCAP, and the patients would not undergo comprehensive liver examinations, leading to potential neglect of hepatic disease. For instance, a patient with SCAP had no diagnosis of hepatic disease in the EMR, but the patient’s serum AST and ALT levels were 121U/L and 108 U/L, respectively. However, the normal ranges for both AST and ALT levels were < 40 IU/L86,87. In fact, the patient had hepatic disease with a high probability84, but the patient could not be diagnosed with hepatic disease due to the absence of other medical examinations.

Myoglobin is a cytoplasmic hemoprotein, which is only expressed in the cardiac myocyte and oxidative skeletal muscle fiber under normal circumstances. Myoglobin plays an oxygen-storage role in the muscle by binding oxygen reversibly via the heme residue, and it releases oxygen under the condition of hypoxia or anoxia88. Recent studies found that myoglobin served as a useful biomarker in the detection of cardiac damage such as acute myocardial infarction89. In this study, both increased myoglobin and cardiovascular disease were risk factors for in-hospital mortality in patients with SCAP (Table 2), suggesting that myoglobin might not be a direct biomarker for in-hospital mortality in SCAP. Namely, myoglobin, as a biomarker for cardiovascular disease, was related to in-hospital mortality in SCAP.

Among arterial BGA parameters (pH, PaCO2, PaO2, BE, and HCO3−), pH and BE were significantly associated with in-hospital mortality in SCAP. BE is a laboratory term to describe the imbalance of acid-base metabolism such as alkalosis and acidosis. A positive value of BE indicates an excess of base or lack of acid, while a negative value of BE indicates an excess of acid or lack of base90. In the present study, the median (range) BE value was 5.6 (0–26.7) mmol/L, all of the BE values were ≥ 0 mmol/L, indicating that these patients with SCAP suffering from an excess of base or lack of acid. In addition, increased pH was associated with increased in-hospital mortality in SCAP. These results suggested that alkalosis was a risk factor for in-hospital mortality in SCAP.

There were some limitations in the study. For instance, all of the patients with SCAP were derived from a single center, resulting in limited contributions to generalize the findings. There was no validation cohort to demonstrate the practicability and accuracy of the nomogram, whether the nomogram has high predictive value in other groups of patients with SCAP is unclear.

Conclusions

In the patients with SCAP, both NLR and BLR were significant but not independent prognostic factors for in-hospital mortality, and were associated with reduced OS, elevated ICU admission rates, and increased ICU mortality. In addition, both NLR and BLR were raised in the patients with SCAP compared to healthy volunteers, and were lowered when the patients were in recovery after treatment. Thus, both higher NLR and higher BLR were related to worse clinical outcomes in the patients with SCAP. In summary, both NLR and BLR had high prognostic value in SCAP.

Data availability

The clinical data of patients with SCAP used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The clinical data of healthy volunteers generated or analyzed during this study are included in the supplementary information file.

Abbreviations

- CAP:

-

community-acquired pneumonia

- SCAP:

-

severe community-acquired pneumonia

- PLR:

-

platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio

- NLR:

-

neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- MLR:

-

monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio

- AECOPD:

-

acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- NSCLC:

-

non-small cell lung cancer

- COVID-19:

-

coronavirus disease 2019

- LOS:

-

length of stay

- BLR:

-

basophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- ELR:

-

eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- IDSA:

-

Joint Guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America

- ATS:

-

American Thoracic Society

- EMR:

-

electronic medical record

- SBP:

-

systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

diastolic blood pressure

- CBC:

-

complete blood count

- LFT:

-

liver function test

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

- RBC:

-

red blood cell

- Hs-Tn:

-

high-sensitivity troponin

- BUN:

-

blood urea nitrogen

- Scr:

-

serum creatinine

- UA:

-

uric acid

- AST:

-

aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- TBIL:

-

total bilirubin

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- PT:

-

prothrombin time

- BNP:

-

brain natriuretic peptide

- Hs-CRP:

-

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- BGA:

-

blood gas analysis

- PaO2 :

-

arterial oxygen tension

- PaCO2 :

-

arterial carbon dioxide tension

- OS:

-

overall survival

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- BE:

-

base excess

- SHAP:

-

severe hospital-acquired pneumonia

- C-index:

-

index of concordance

- DCA:

-

decision curve analysis

- AUC:

-

area under the curve

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic

- CURB:

-

confusion, blood urea nitrogen > 7 mmol/l, respiratory rate > 30/min, and low blood pressure (systolic < 90 mmHg or diastolic < 60 mmHg

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- ALI:

-

acute lung injury

- PSI:

-

pneumonia severity index

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- ISH:

-

International Society of Hypertension

- NAFLD:

-

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

References

Phua, J. et al. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: timely management measures in the first 24 hours. Crit. Care 20, 237. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1414-2 (2016).

Huang, D. et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with mortality in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Crit. Care 25, 419. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-021-03841-w (2021).

Liao, Q. Q. et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio (MLR), and Eosinophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (ELR) as biomarkers in patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD). Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 19, 501–518. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S447519 (2024).

Yuan, C. et al. Elevated pretreatment neutrophil/white blood cell ratio and monocyte/lymphocyte ratio predict poor survival in patients with curatively resected non-small cell lung cancer: results from a large cohort. Thorac. Cancer. 8, 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.12454 (2017).

Zinellu, A. et al. Blood cell count derived inflammation indexes in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung 198, 821–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00408-020-00386-7 (2020).

Citu, C. et al. The predictive role of NLR, d-NLR, MLR, and SIRI in COVID-19 mortality. Diagnostics https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics12010122 (2022).

Fors, M. et al. Sex-dependent performance of the neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte, monocyte-to-Lymphocyte, platelet-to-lymphocyte and Mean platelet volume-to-platelet ratios in discriminating COVID-19 severity. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 822556. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.822556 (2022).

Qi, X., Dong, Y., Lin, X. & Xin, W. Value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, platelet to Lymphocyte Ratio, and red blood cell distribution width in evaluating the prognosis of children with severe pneumonia. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat Med. 2021, 1818469. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/1818469 (2021).

Yang, Z. et al. Comparisons of neutrophil-, monocyte-, eosinophil-, and basophil- lymphocyte ratios among various systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases. APMIS 125, 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/apm.12722 (2017).

Bozan, N. et al. Mean platelet volume, red cell distribution width, platelet-to-lymphocyte and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and their relationships with high-frequency hearing thresholds. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 273, 3663–3672. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-016-3980-y (2016).

Mercan, R. et al. The Association between Neutrophil/Lymphocyte Ratio and Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 30, 597–601. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcla.21908 (2016).

Wang, K. et al. The Prognostic Value of multiple systemic inflammatory biomarkers in preoperative patients with non-small cell Lung Cancer. Front. Surg. 9, 830642. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2022.830642 (2022).

Hadadi, A. et al. Baseline basophil and basophil-to-lymphocyte status is associated with clinical outcomes in metastatic hormone sensitive prostate cancer. Urol. Oncol. 40 (271 e279-271 e218). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2022.03.016 (2022).

Mandell, L. A. et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44 (Suppl 2), 27–72. https://doi.org/10.1086/511159 (2007).

Attaway, A. H., Scheraga, R. G., Bhimraj, A., Biehl, M. & Hatipoglu, U. Severe covid-19 pneumonia: pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ 372, n436. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n436 (2021).

Martin-Loeches, I. et al. ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07033-8 (2023).

Martin-Loeches, I. et al. ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur. Respir J. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00735-2022 (2023).

Metlay, J. P. & Waterer, G. W. Update in adult community-acquired pneumonia: key points from the new American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America 2019 guideline. Curr. Opin. Pulm Med. 26, 203–207. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000671 (2020).

Verdecchia, P., Reboldi, G. & Angeli, F. The 2020 International Society of Hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines - key messages and clinical considerations. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 82, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2020.09.001 (2020).

Sligl, W. I. & Marrie, T. J. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Crit. Care Clin. 29, 563–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccc.2013.03.009 (2013).

Metlay, J. P. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am. J. Respir Crit. Care Med. 200, e45–e67. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST (2019).

Nair, G. B. & Niederman, M. S. Updates on community acquired pneumonia management in the ICU. Pharmacol. Ther. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107663 (2021).

Aliberti, S., Dela Cruz, C. S., Amati, F., Sotgiu, G. & Restrepo, M. I. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 398, 906–919. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00630-9 (2021).

Zhu, K. W. et al. Pharmacokinetics and bioequivalence of Two Formulations of Rosuvastatin Following Single-Dose Administration in Healthy Chinese Subjects under Fasted and Fed Conditions. Clin. Pharmacol. Drug Dev. 11, 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpdd.1112 (2022).

Rosner, B., Glynn, R. J. & Lee, M. L. The Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired comparisons of clustered data. Biometrics 62, 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0420.2005.00389.x (2006).

Kim, J. H. Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 72, 558–569. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19087 (2019).

Johnston, R., Jones, K. & Manley, D. Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: a cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Qual. Quant. 52, 1957–1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0584-6 (2017).

Beasley, T. M. Tests of mediation: paradoxical decline in statistical power as a function of Mediator Collinearity. J. Exp. Educ. 82, 283–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2013.813360 (2013).

Vatcheva, P., Lee, M. & K. & Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol. Open Access 06 https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-1165.1000227 (2016).

van Schaik, P., Peng, Y., Ojelabi, A. & Ling, J. Explainable statistical learning in public health for policy development: the case of real-world suicide data. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0796-7 (2019).

Lu, K. et al. Efficacy and safety of different doses of Rivaroxaban and Risk factors for bleeding in Elderly patients with venous thromboembolism: a Real-World, Multicenter, Observational, Cohort Study. Adv. Therapy. 41, 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02717-5 (2023).

Beesley, L. J. et al. Multiple imputation with missing data indicators. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 30, 2685–2700. https://doi.org/10.1177/09622802211047346 (2021).

Demler, O. V., Pencina, M. J. & D’Agostino, R. B. Misuse of DeLong test to compare AUCs for nested models. Stat. Med. 31, 2577–2587. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5328 (2012).

Liao, Q. Q. et al. Long-term prognostic factors in patients with Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-Associated Vasculitis: a 15-Year Multicenter Retrospective Study. Front. Immunol. 13, 913667. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.913667 (2022).

Lim, W. S. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax 58, 377–382. https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax.58.5.377 (2003).

Rider, A. C. & Frazee, B. W. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am. 36, 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2018.07.001 (2018).

Tang, J. et al. Admission IL-32 concentration predicts severity and mortality of severe community-acquired pneumonia independently of etiology. Clin. Chim. Acta. 510, 647–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.035 (2020).

Karasuyama, H., Shibata, S., Yoshikawa, S. & Miyake, K. Basophils, a neglected minority in the immune system, have come into the limelight at last. Int. Immunol. 33, 809–813. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxab021 (2021).

Karasuyama, H. & Yamanishi, Y. Basophils have emerged as a key player in immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 31, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2014.07.004 (2014).

Min, B. Basophils: what they ‘can do’ versus what they ‘actually do’. Nat. Immunol. 9, 1333–1339. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.f.217 (2008).

Karasuyama, H., Miyake, K., Yoshikawa, S., Kawano, Y. & Yamanishi, Y. How do basophils contribute to Th2 cell differentiation and allergic responses? Int. Immunol. 30, 391–396. https://doi.org/10.1093/intimm/dxy026 (2018).

Schwartz, C., Eberle, J. U. & Voehringer, D. Basophils in inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 778, 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.04.049 (2016).

Inaba, K. et al. Proinflammatory role of basophils in oxazolone-induced chronic intestinal inflammation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 37, 1768–1775. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.15964 (2022).

Pieralli, F. et al. Acute cardiovascular events in patients with community acquired pneumonia: results from the observational prospective FADOI-ICECAP study. BMC Infect. Dis. 21 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05781-w (2021).

Martin-Loeches, I. et al. A Multicentric Observational Study to Determine Myocardial Injury in Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia (sCAP). Antibiotics. (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12121710

Cilli, A. et al. Acute cardiac events in severe community-acquired pneumonia: a multicenter study. Clin. Respir. J. 12, 2212–2219. https://doi.org/10.1111/crj.12791 (2018).

Anderson, R. & Feldman, C. The global burden of community-acquired pneumonia in adults, Encompassing Invasive Pneumococcal Disease and the prevalence of its Associated Cardiovascular events, with a focus on Pneumolysin and Macrolide Antibiotics in Pathogenesis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241311038 (2023).

Tralhao, A. & Povoa, P. Cardiovascular events after community-acquired pneumonia: A global perspective with systematic review and Meta-analysis of Observational studies. J. Clin. Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9020414 (2020).

Feldman, C., Anderson, R. & Community-Acquired, P. Pathogenesis of Acute Cardiac events and potential adjunctive therapies. Chest 148, 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.15-0484 (2015).

Hoang Ngo, T. et al. The combination of CYP2C19 polymorphism and inflammatory cell ratios in prognosis cardiac adverse events after acute coronary syndrome. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcrp.2023.200222 (2023).

Larmann, J. et al. Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio are associated with major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in coronary heart disease patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20, 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-020-01500-6 (2020).

Selcuk, N. et al. Sarcopenia is a risk factor for major adverse cardiac events after surgical revascularization for critical limb ischemia. Vascular 31, 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/17085381211059383 (2023).

Tamaki, S. et al. Combination of Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios as a novel predictor of Cardiac death in patients with Acute Decompensated Heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: a Multicenter Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 12, e026326. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.122.026326 (2023).

Kuikel, S. et al. Neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of adverse outcome in patients with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review. Health Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1002/hsr2.630 (2022).

Oosterheert, J. J., Bonten, M. J., Hak, E., Schneider, M. M. & Hoepelman A. I. severe community-acquired pneumonia: what’s in a name? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 16, 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001432-200304000-00012 (2003).

Almirall, J., Serra-Prat, M., Bolíbar, I. & Balasso, V. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a systematic review of Observational studies. Respiration 94, 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479089 (2017).

Wongsurakiat, P. & Chitwarakorn, N. Severe community-acquired pneumonia in general medical wards: outcomes and impact of initial antibiotic selection. BMC Pulm. Med. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-0944-1 (2019).

Marti, C. et al. Prediction of severe community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11447 (2012).

Brown, S. M. & Dean, N. C. Defining and predicting severe community-acquired pneumonia. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 23, 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283368333 (2010).

Meng, Y., Zhang, L., Huang, M. & Sun, G. Blood heparin-binding protein and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as indicators of the severity and prognosis of community-acquired pneumonia. Respir. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107144 (2023).

Liu, Q., Sun, G. & Huang, L. Association of the NLR, BNP, PCT, CRP, and D-D with the severity of community-acquired pneumonia in older adults. Clin. Lab. https://doi.org/10.7754/Clin.Lab.2023.220330 (2023).

Liu, X., Li, J., Sun, L., Wang, T. & Liang, W. The association between neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Inflammopharmacology. 31, 2237–2244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-023-01273-2 (2023).

García-Escobar, A. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio an inflammatory biomarker, and prognostic marker in heart failure, cardiovascular disease and chronic inflammatory diseases: new insights for a potential predictor of anti-cytokine therapy responsiveness. Microvasc. Res. 150, 104598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mvr.2023.104598 (2023).

Zahorec, R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratislava Med. J. 122, 474–488. https://doi.org/10.4149/bll_2021_078 (2021).

Wechsler, M. et al. (ed, E.) Eosinophils in Health and Disease: a state-of-the-art review. Mayo Clin. Proc. 96 2694–2707 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.04.025 (2021).

Macchia, I. et al. Eosinophils as potential biomarkers in respiratory viral infections. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1170035 (2023).

Ravin, K. A. & Loy, M. The Eosinophil in infection. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 50, 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-015-8525-4 (2015).

Cottin, V. Eosinophilic Lung diseases. Clin. Chest. Med. 37, 535–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccm.2016.04.015 (2016).

O’Sullivan, J. A. & Bochner, B. S. Eosinophils and eosinophil-associated diseases: an update. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 505–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.022 (2018).

Pu, J. et al. Blood eosinophils and clinical outcomes in inpatients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 18, 169–179. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S396311 (2023).

Kolsum, U. et al. Blood and sputum eosinophils in COPD; relationship with bacterial load. Respir. Res. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0570-5 (2017).

Choi, J. et al. The association between blood eosinophil percent and bacterial infection in acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 14, 953–959. https://doi.org/10.2147/copd.S197361 (2019).

Loukides, S. et al. Independent factors associate with hospital mortality in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring intensive care unit admission: focusing on the eosinophil-to-neutrophil ratio. Plos One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0218932 (2019).

Liu, H. et al. The association between blood eosinophils and clinical outcome of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir. Med. 222, 107501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2023.107501 (2024).

Qiu, Y. et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio Predicts Mortality in Adult Renal Transplant Recipients with Severe Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Pathogens (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9110913

Mujakovic, A. et al. Can neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and proatherogenic risk factors improve the accuracy of pneumonia severity index in the prediction of community acquired pneumonia outcome in healthy individuals? Med. Glas (Zenica) https://doi.org/10.17392/1464-22 (2022).

Enersen, C. C. et al. The ratio of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte and association with mortality in community-acquired pneumonia: a derivation-validation cohort study. Infection https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-023-01992-2 (2023).

Zhao, L. H., Chen, J. & Zhu, R. X. The relationship between frailty and community-acquired pneumonia in older patients. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 35, 349–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-022-02301-x (2023).

Viasus, D. et al. Community-acquired pneumonia in patients with liver cirrhosis. Medicine 90, 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e318210504c (2011).

Gjurašin, B., Jeličić, M., Kutleša, M. & Papić, N. The impact of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease on severe community-acquired pneumonia outcomes. Life https://doi.org/10.3390/life13010036 (2022).

Nseir, W. B., Mograbi, J. M., Amara, A. E., Abu Elheja, O. H. & Mahamid, M. N. non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and 30-day all-cause mortality in adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia. QJM: Int. J. Med. 112, 95–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcy227 (2019).

Ferrer-Inaebnit, E., Molina-Romero, F. X., Segura-Sampedro, J. J., González-Argenté, X. & Morón Canis, J. M. A review of the diagnosis and management of liver hydatid cyst. Rev. Española Enferm. Dig.. https://doi.org/10.17235/reed.2021.7896/2021 (2021).

Sun, M. J., Cao, Z. Q. & Leng, P. The roles of galectins in hepatic diseases. J. Mol. Histol. 51, 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10735-020-09898-1 (2020).

Pratt, D. S. & Kaplan, M. M. Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 1266–1271. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200004273421707 (2000).

Kubilay, N. Z., Sengel, B. E., Wood, K. E. & Layon, A. J. Biomarkers in hepatic disease. J. Intensive Care Med. 31, 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885066614554897 (2014).

Najmy, S. et al. Redefining the normal values of serum aminotransferases in healthy Indian males. J. Clin. Exp. Hepatol. 9, 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jceh.2018.06.003 (2019).

Sohn, W. et al. Upper limit of normal serum alanine and aspartate aminotransferase levels in Korea. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 28, 522–529. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07143.x (2013).

Ordway, G. A. & Garry, D. J. Myoglobin: an essential hemoprotein in striated muscle. J. Exp. Biol. 207, 3441–3446. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.01172 (2004).

Asl, S. K. & Rahimzadegan, M. The recent progress in the early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction based on myoglobin biomarker: Nano-aptasensors approaches. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 211, 114624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2022.114624 (2022).

Juern, J., Khatri, V. & Weigelt, J. Base excess: a review. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 73, 27–32. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318256999d (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the medical staff for providing us more or less help in the collection of clinical data, and are especially grateful to the clinicians who provided guidance on our research.

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Care Commission of Sichuan Province (No.Chuanganyan2023-220), and the project of “Machine learning-based multidrug-resistant bacterial infection risk factor screening model and risk early warning model research—taking CRO infection as an example”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. CXJ, XB, LQQ, ZJC, DS, LXX, and CZJ were responsible for clinical data collection and arrangement. Among these authors, CXJ and XB were key contributors. ZKW was responsible for statistical analysis. Both YXQ and YY were responsible for guidance and supervision. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ZKW, and ZKW was also responsible for submission, and the other co-authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed on the final version of the article to be published. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Author Ke-Wei Zhu is employed by GuangZhou BaiYunShan Pharmaceutical Holdings CO.,LTD. BaiYunShan Pharmaceutical General Factory, Guangzhou, China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, XJ., Xie, B., Zhu, KW. et al. Prognostic value of the platelet, neutrophil, monocyte, basophil, and eosinophil to lymphocyte ratios in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia (SCAP). Sci Rep 14, 30406 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80727-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80727-1