Abstract

Background The stress hyperglycemia ratio (SHR) indicates relative hyperglycemia levels. Research on the impact of SHR on mortality in coronary heart disease (CHD) patients in intensive care is limited. This study explores the predictive accuracy of SHR for the prognosis of CHD patients in the ICU. Methods This study included 2,059 CHD patients from the American Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care (MIMIC-IV) database. SHR was determined using the formula: SHR = (admission glucose) (mmol/L) / (1.59 * HbA1c [%] – 2.59). Subjects were stratified into quartiles based on SHR levels to examine the correlation between SHR and in-hospital mortality. The restricted cubic splines and Cox proportional hazards models were employed to assess this association, while Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was executed to ascertain the mortality rates across the SHR quartiles. Results Among the 2059 participants (1358 men), the rates of in-hospital and ICU mortality were 8.5% and 5.25%, respectively. Analysis showed SHR as a significant predictor of increased risk for both in-hospital (HR,1.16, 95% CI: 1.02–1.32, P = 0.022) and ICU mortality (HR, 1.16, 95% CI: 1.01–1.35, P = 0.040) after adjustments. A J-shaped relationship was noted between SHR and mortality risks (p for non-linearity = 0.002, respectively). Kaplan-Meier analysis confirmed substantial differences in in-hospital and ICU mortality across SHR quartiles. Conclusions SHR significantly predicts in-hospital and ICU mortality in critically ill CHD patients, indicating that higher SHR levels correlate with longer ICU stays and increased mortality. This underscores the potential of SHR as a prognostic marker for ICU CHD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) remains a critical global public health concern, leading to high morbidity and mortality worldwide. It adversely affects health quality and increases healthcare costs, despite advancements in prevention and treatment methods1,2,3. In intensive care units (ICU), CHD patients often face extended stays and high mortality rates, presenting a major challenge to healthcare systems and society4. Identifying CHD patients at high risk is crucial for improving their prognosis.

Stress hyperglycemia, which commonly occurs in severe patients, signals illness severity5. This condition triggers a temporary metabolic response, elevating glucose levels during emergencies, and is linked to poorer clinical outcomes6,7. The association between hyperglycemia and poor outcomes in patients can be partly explained by the amplification of inflammatory and neurohormonal reactions in more serious cases of illness8. The Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio (SHR), by comparing Admission Blood Glucose (ABG) with baseline Glycosylated Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), provides a refined assessment of relative hyperglycemia9,10,11,12, offering predictive insights into potential health deterioration8.

In the ICU settings, patients with CHD are often in a high stress state, which may aggravate the condition and affect the prognosis. One study reported that 46.8% of ICU patients had CHD13. These ICU patients with CHD often experience more complications, significantly increasing mortality rates, length of hospital stay, and healthcare costs14. However, research on the prognosis of these critically ill patients with CHD remains limited15. Stress hyperglycemia, that is, an increase in blood sugar under stress conditions such as diseases or trauma, is often regarded as a response of the body to serious illness6,16,17. In ICU patients with CHD, stress hyperglycemia can lead to coronary atherosclerotic plaque instability and rupture, exacerbating myocardial ischemia, which may further result in myocardial infarction, acute heart failure, and malignant arrhythmias, severely impacting patient outcomes18,19. Therefore, the level of stress hyperglycemia can indirectly reflect the severity of diseases and the body’s ability to respond to stresses. Understanding the stress hyperglycemia level can help doctors pay more attention to blood sugar control during treatment, adjust insulin dosage or other hypoglycemic measures in a timely manner, so as to reduce the damage of hyperglycemia to the body and improve the prognosis of patients9,20. In addition, the management of stress hyperglycemia can also help reduce the risk of complications such as infection and multiple organ dysfunction in patients19. Due to the differences in stress response capabilities and severity of diseases, the level of stress hyperglycemia may also vary. By stratifying patients by stress hyperglycemia ratio, doctors can formulate personalized treatment plans for patients at different levels to achieve precision medicine.

Research has consistently shown that higher SHR values are associated with worse outcomes in various cardiac conditions, including acute myocardial infarction (AMI)9,21,22, coronary artery disease20, heart failure (HF)23,24, and ischemic stroke25,26. Nonetheless, the exploration of SHR’s influence on mortality among CHD patients receiving ICU care remains inadequately addressed. This investigation seeks to elucidate the association between SHR and all-cause mortality in this patient group.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective observational study analyzed data from the MIMIC-IV database, which encompasses records of ICU patients at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center spanning from 2008 to 201927. The author (Xiaofang Chen) obtained the necessary Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative license and permissions for database access.

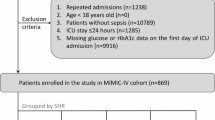

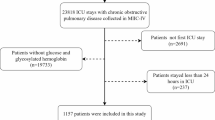

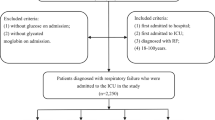

The analysis focused on 15,402 individuals, aged 18 or older, diagnosed with CHD and admitted to the ICU on a non-consecutive basis. For those with multiple admissions, only the data on the initial stay was included. Patients lacking first-day admission data for glycosylated HbA1c and glucose were excluded, resulting in a final cohort of 2,059 patients (Fig. 1). This cohort was divided into quartiles based on their SHR on the first ICU day.

Data collection

Data was extracted using Structured Query Language (SQL) queries in PostgreSQL (version 14.2), focusing on patient demographics, vital signs, admission severity scores (measured by Acute physiology score III (APSIII), and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score), and first 24-hour ICU laboratory results (red blood cell (RBC), white blood cells (WBC), neutrophils, lymphocyte, hemoglobin, platelets, sodium, potassium, total glyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), glucose, HbA1c, albumin, pH, partial pressure of CO2 (PCO2), partial oxygen pressure (PO2), lactate, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), serum creatinine (Scr), creatine kinase (CK), creatine kinase MB (CKMB), and troponin T (Tnt)).

Comorbidities were delineated using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) and ICD-9 codes, including CHD, HF, hypertension, atrial fibrillation (AF), dyslipidemia, respiratory failure, stroke, type 2 diabetes, acute renal failure (ARF), chronic kidney disease (CKD), AMI, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and sepsis. The follow-up commenced at ICU admission and concluded at the patient’s death.

Due to the prevalence of missing data in MIMIC-IV, the study employed multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) to mitigate bias in data analysis, adhering to Fully Conditional Specification for imputing each incomplete variable28. Among the variables included in the study, the missing value was 50.7% for LDL-C, 49.0% for HDL-C, 48.1% for TC, 46.3% for BMI, 46.3% for TG, 42.2% for lymphocytes, 42.2% for neutrophils, 38.5% for lactate, 37.8% for PCO2, 37.8% for PO2, 37.0% for Tnt, 36.6% for albumin, 36.2% for PH, 34.5% for CK, 29.2% for CKMB, 23.2% for ALT, 22.9% for AST, and 0.5% for platelets. All the above independent variables were included in the imputation model for imputation modeling. Due to the substantial missing data, we performed a sensitivity analysis comparing imputed and non-imputed datasets. The comparison demonstrated consistent trends between both models (Supplementary Table 1).

Primary outcomes and clinical definitions

The primary outcome of this research was all-cause mortality, encompassing both in-hospital and ICU mortality rates. SHR was determined using the formula: SHR = (admission glucose) (mmol/L) / (1.59 * HbA1c [%] – 2.59)8. CHD was defined as stable angina, unstable angina, myocardial infarction (MI), and ischemic heart disease3. CKD was defined by an estimated glomerular filtration rate of 60 ml/min/1.73 m2or less, as delineated by the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula29. Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) was diagnosed following the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria, which stipulate an increase in SCr to ≥ 1.5 times baseline within the previous seven days, an SCr rise of ≥ 0.3 mg/dl within 48 h, or urine output less than 0.5 ml/kg/h for six hours or more30.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were summarized as means ± standard deviation or medians with interquartile ranges, and were analyzed via the ANOVA analysis. Categorical data, expressed as frequencies and percentages, were compared using Fisher’s exact test or Pearson’s chi-square test as appropriate. For variables with significant differences, the Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to perform post-hoc multiple comparison to correct P values to observe the differences between groups. Survival differences across varying levels of SHR were examined through Kaplan-Meier analysis, while disparities were tested using log-rank methods.

The association between SHR and the primary outcome was quantified using Cox proportional hazard models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Several models were adjusted for variables associated with prognosis: Model 1 applied no adjustments; Model 2 was adjusted for demographic and baseline health characteristics, specifically age, sex, and body mass index (BMI); Model 3 was additionally adjusted for variables related to patient health and disease status, encompassing age, sex, BMI, HF, type 2 diabetes, AKI, CKD, AMI, PCI, AF, sepsis, TG, TC, High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL), sodium, potassium, heart rate, and Mean Blood Pressure (MBP). SHR values were analyzed as both continuous and categorical variables, the latter with the lowest quartile serving as a reference. A restricted cubic splines model was leveraged to explore the dose-response relationship between SHR and outcomes.

To assess the prognostic consistency of SHR across various demographics and medical histories, subgroup analyses were executed according to gender, age (above versus equal to or below 65 years), BMI (30 kg/m2 or higher versus lower), and the existence of specific medical conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, AMI, CKD, HF, AF and sepsis. Likelihood ratio tests were implemented to ascertain the link between SHR and these stratification variables.

Data analysis was performed with R software (version 4.2.2), and a two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was indicative of statistical significance.

Results

This study included 2,059 patients, with a mean age of 69.92 (SD = 12.88) years; 65.95% (1,358) were male. The average SHR across all patients was 1.20 ± 0.61. In-hospital and ICU mortality rates were 8.50% and 5.25%, respectively.

Baseline characteristics

Participants were stratified into quartiles based on admission SHR levels [Q1: 0.19–0.88; Q2: 0.88–1.07; Q3: 1.07–1.37; Q4: 1.37–15.09). The average SHR values for these groups were 0.74 ± 0.13, 0.97 ± 0.55, 1.20 ± 0.08, and 1.88 ± 0.85, respectively. Patients in the Q4 group had more severe illness indicators, including faster heart rates at admission, and higher incidences of HF, AF, respiratory failure, AKI, CKD, and AMI. This group also showed higher potassium, BUN, and Scr levels, but lower albumin, pH, and PO2 levels compared to those with lower SHR values ((all P < 0.05).

An increase in SHR was associated with higher WBC, neutrophils, glucose, lactate, CK, and Tnt levels, but lower lymphocyte, RBC, and sodium levels (all with p-values less than 0.05). An elevated SHR was associated with extended ICU stays (3.09 vs. 3.29 vs. 4.06 vs. 5.07 days, P = 0.003) and higher ICU (1.94% vs. 3.69% vs. 4.47% vs. 10.87%, P<0.001) and in-hospital mortality (4.47% vs. 6.21% vs. 7.59% vs. 15.73%, P<0.001). Patients in Q4 experienced longer hospital stays compared to those in lower quartiles. More detailed baseline characteristics are provided in Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis demonstrated significant disparities in the in-hospital mortality across SHR quartiles during both 1-month and 3-month follow-up periods (log-rank p <0.001 for both, Fig. 2a and b). Similarly, significant differences in ICU mortality were noted at 1-month and 3-month follow-ups (log-rank p less than 0.001 for both, Fig. 2c and d).

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis curves for all-cause mortality. Footnote SHR quartiles: Q1: 0.19–0.88; Q2: 0.88–1.07; Q3: 1.07–1.37; Q4: 1.37–15.09. Kaplan–Meier curves showing probability of hospital mortality according to groups at 1 month (A), and 3 months (B), and ICU mortality according to groups at 1 month (C), and 3 months (D).

The Cox proportional hazards model affirmed a significant correlation between SHR and in-hospital mortality in both Model 1 (HR, 1.17 [95%CI 1.07–1.28] P<0.001) and Model 3 (HR, 1.16 [95%CI 1.02–1.32] P = 0.022) when the SHR was considered a continuous variable. For nominal SHR, significant associations with in-hospital mortality were observed in both Model 1 (Q1 vs. Q2: HR, 1.72 [95% CI 1.01–2.94] P = 0.048; Q3: HR, 1.96 [95% CI 1.17–3.28] P = 0.01; Q4: HR, 3.02 [95% CI 1.90–4.80] P<0.001) and Model 3 (Q1 vs. Q2: HR, 1.62 [95% CI 0.94–2.79] P = 0.080; Q3: HR, 1.71 [95% CI 1.01–2.89] P = 0.045; Q4: HR, 2.67 [95% CI 1.64–4.34] P < 0.001). The risk of in-hospital mortality escalates with increasing SHR (Table 2). A similar trend was noted for ICU mortality. The restricted cubic splines model suggested a J-shaped relationship between SHR and the risks of both in-hospital and ICU mortality (P for non-linearity = 0.002, Fig. 3). This study used the graphical method to prove the premise of the Cox model. It can be observed that the curves on the KM graph did not intersect. Hence, the premise of the Cox model is proved to be valid. Meanwhile, we calculated the AIC values of Model 1-Model 3 when SHR was used as a continuous variable and a nominal variable (Table 3) to avoid possible overfitting. As shown in Table 3, the AIC value of Model3 was the lowest. According to the AIC values, the final adjusted Model 3 was considered the best model.

Subgroup analyses

To delve deeper into the impact of SHR on primary outcomes, subgroup analyses were executed based on gender, age, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, AMI, CKD, HF, AF and sepsis (Fig. 4). Notable interactions indicated that SHR was particularly efficient for predicting the risk of mortality in females, individuals older than 65 years, and patients with HF but without AMI, CKD or sepsis.

Discussion

This study found a strong link between the SHR and in-hospital and ICU mortality rates in patients with CHD. An elevated SHR was associated with extended ICU stays and higher ICU and in-hospital mortality. Notably, patients in the Q4 had significantly longer hospital stays than those in other groups. Our subgroup analysis revealed that SHR consistently predicted mortality in patients, including those with HF, highlighting its stable prognostic value in CHD.

This research is pioneering in analyzing the relationship of SHR with all-cause mortality among CHD patients using a U.S. public critical care database. The findings underscore SHR as a reliable independent predictor of higher mortality in these patients, even when considering various confounding factors. This study introduces a direct, effective method for assessing the risk of stress hyperglycemia among CHD patients admitted to the ICU.

Hospitalized patients with hyperglycemia, particularly those admitted for HF, MI, ischemic stroke, or severe illness, often face increased mortality risks31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Hyperglycemia can signal a temporary physiological response to acute illness, defined by a relative glucose level rise due to inflammatory and neurohormonal disruptions from severe conditions. This stress response involves the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sympathoadrenal system, increasing proinflammatory cytokine release and inducing stress hyperglycemia5.

Previous research has debated the reliability of admission glucose levels as an indicator of stress hyperglycemia, especially in diabetic patients with poor glycemic control39. Studies by Gregory W. et al.8 and Marenzi et al.40 have shown that SHR, unlike admission glucose levels, is significantly associated with critical illness and provides a better prediction of in-hospital mortality in AMI cases. SHR offers a new perspective on the link between hyperglycemia and clinical outcomes by adjusting glucose levels to HbA1c. Given the widespread availability of glucose and HbA1c testing, this simple calculation can provide valuable prognostic information for hospitalized patients.

Numerous studies have shown a strong link between the SHR and poor outcomes. Stress hyperglycemia is a proven marker for elevated mortality risks in AMI patients31,37,41,42. Additionally, evidence indicates that in non-obstructive MI, stress hyperglycemia correlates with more extensive myocardial cell death and worse prognosis, both short-term and long-term43,44. Research by Li et al.45has identified a U-shaped relationship between SHR and mortality in critical conditions, suggesting both high and low SHR levels worsen the prognosis of acute decompensated HF and diabetes, as noted by Zhou et al. Sia et al. highlighted SHR as a key independent factor for one-year mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) cases, irrespective of diabetes status46. Xu et al. have demonstrated the link between SHR and 30-day mortality in STEMI patients, noting that adding SHR to the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) risk score improves its predictive power47. Zhang et al. have identified increased SHR as an independent risk factor for mortality in ICU patients48.

The underlying mechanism of the connection between SHR and mortality may involve diminished endothelium-dependent vasodilation, reduced platelet anti-aggregation, and increased sympathetic nerve activity due to inflammation49,50,51. Stress hyperglycemia contributes to oxidative stress and inflammation, worsening endothelial dysfunction6, thrombosis, and ischemia-reperfusion injury, thereby increasing myocardial damage21. It also promotes a pro-thrombotic state and activates the neuroendocrine system, increasing catecholamines and cytokines, which impair vascular endothelial function44,52. These mechanisms help explain the connection between hyperglycemia and adverse outcomes, especially in severe illnesses, by exacerbating inflammatory and neurohormonal responses [8].

Our analysis substantiates SHR as an independent indicator of mortality in ICU patients with CHD. Our findings can facilitate the early identification of high-risk CHD patients within ICU. Strict glycemic control is required to improve outcomes in this high-morbidity and high-mortality population.

Strengths and limitations

The principal strength of this investigation lies in confirming the SHR as a significant independent predictor of mortality in critically ill CHD patients upon ICU admission in a U.S. cohort. However, given the retrospective and observational design of the study and the inherent limitations of the MIMIC-IV database, it is impossible to examine causal inferences and account for variables such as disease severity, baseline characteristics, admission diagnoses, and participants’ socioeconomic status, potentially leading to biased results. Moreover, as a monocentric study with a relatively constrained sample size, despite comprehensive multivariate adjustments and subgroup analyses, this study may not fully eliminate bias from unconsidered confounding factors. The analysis emphasizes the baseline prognostic value of SHR in CHD without examining SHR fluctuations during hospital stays. Hence, further investigation is warranted to ascertain whether SHR changes could be used to predict mortality. Prospective cohort studies are needed to confirm our findings.

Conclusions

This study underscores the utility of SHR as a prognostic tool for forecasting in-hospital and ICU mortality among critically ill CHD patients. Further research, particularly randomized studies, is required to examine how glycemic control based on SHR might enhance outcomes in those with severe CHD.

Data availability

Extracted data are available on request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- SHR:

-

Stress hyperglycemia ratio

- CHD:

-

Coronary heart disease

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- MIMIC-IV:

-

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care

- ABG:

-

Admission Blood Glucose

- HbA1c:

-

Hemoglobin A1c

- AMI:

-

Acute myocardial infarction

- SQL:

-

Structured Query Language

- APSIII:

-

Acute physiology score III

- RBC:

-

Red blood cell

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

- TG:

-

Total glyceride

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- PCO2 :

-

Partial pressure of CO2

- PO2 :

-

Partial oxygen pressure

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- Scr:

-

Serum creatinine

- CK:

-

Creatine kinase

- CKMB:

-

Creatine kinase MB

- Tnt:

-

Troponin T

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision

- ICD-9:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- ARF:

-

Acute renal failure

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- CABG:

-

Coronary artery bypass grafting

- MICE:

-

Multivariate imputation by chained equations

- CKD-EPI:

-

CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration

- AKI:

-

Acute Kidney Injury

- KDIGO:

-

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals (s)

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- HDL:

-

High-Density Lipoprotein

- MBP:

-

Mean Blood Pressure

References

Vaduganathan, M., Mensah, G. A., Turco, J. V., Fuster, V. & Roth, G. A. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular diseases and Risk: a compass for Future Health. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 80, 2361–2371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.005 (2022).

Duggan, J. P., Peters, A. S., Trachiotis, G. D. & Antevil, J. L. Epidemiology of coronary artery disease. Surg. Clin. North. Am. 102, 499–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2022.01.007 (2022).

Malakar, A. K. et al. A review on coronary artery disease, its risk factors, and therapeutics. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 16812–16823. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.28350 (2019).

Vincent, J. L. et al. Assessment of the worldwide burden of critical illness: the intensive care over nations (ICON) audit. Lancet Respir Med. 2, 380–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(14)70061-x (2014).

Marik, P. E. & Bellomo, R. Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response! Crit. Care. 17, 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc12514 (2013).

Dungan, K. M., Braithwaite, S. S. & Preiser, J. C. Stress hyperglycaemia. Lancet 373, 1798–1807. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60553-5 (2009).

Mifsud, S., Schembri, E. L. & Gruppetta, M. Stress-induced hyperglycaemia. Br. J. Hosp. Med. (Lond). 79, 634–639. https://doi.org/10.12968/hmed.2018.79.11.634 (2018).

Roberts, G. W. et al. Relative hyperglycemia, a marker of critical illness: introducing the stress hyperglycemia ratio. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism. 100, 4490–4497. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2015-2660 (2015).

Yang, J. et al. The impact of the stress hyperglycemia ratio on short-term and long-term poor prognosis in patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: insight from a large cohort study in Asia. Diabetes Care. 45, 947–956. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-1526 (2022).

Cui, K. et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a prospective, nationwide, and multicentre registry. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 38, e3562. https://doi.org/10.1002/dmrr.3562 (2022).

Fu, R. et al. Fasting stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital mortality after acute myocardial infarction in patients with different glucose metabolism status: results from China acute myocardial infarction registry. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 196, 110241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110241 (2023).

Wang, M., Su, W., Cao, N., Chen, H. & Li, H. Prognostic implication of stress hyperglycemia in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01790-y (2023).

Beauvais, F. et al. First symptoms and health care pathways in hospitalized patients with acute heart failure: ICPS2 survey. A report from the Heart Failure Working Group (GICC) of the French Society of Cardiology. Clin. Cardiol. 44, 1144–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.23666 (2021).

van Diepen, S. et al. Prevention of critical care complications in the coronary intensive care unit: protocols, bundles, and insights from Intensive Care studies. Can. J. Cardiol. 33, 101–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2016.06.011 (2017).

Zhang, R. et al. Independent effects of the triglyceride-glucose index on all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease: analysis of the MIMIC-III database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01737-3 (2023).

Marik, P. E. & Bellomo, R. Stress hyperglycemia: an essential survival response! Crit. Care Med. 41, e93–94. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318283d124 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. Stress hyperglycemia is Associated with an increased risk of subsequent development of diabetes among bacteremic and nonbacteremic patients. Diabetes Care. 45, 1438–1444. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-1682 (2022).

D’Onofrio, N. et al. MicroRNA-33 and SIRT1 influence the coronary thrombus burden in hyperglycemic STEMI patients. J. Cell. Physiol. 235, 1438–1452. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.29064 (2020).

Schmitz, T. et al. Prognostic value of stress hyperglycemia ratio on short- and long-term mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Acta Diabetol. 59, 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-022-01893-0 (2022).

Xu, W. et al. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: insights from a large cohort study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01645-y (2022).

Chen, G. et al. Association between Stress Hyperglycemia Ratio and In-hospital outcomes in Elderly patients with Acute myocardial infarction. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 698725. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.698725 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Impact of stress hyperglycemia ratio on mortality in patients with critical acute myocardial infarction: insight from American MIMIC-IV and the Chinese CIN-II study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02012-1 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio and in-hospital prognosis in non-surgical patients with heart failure and type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01728-w (2022).

Palma, D. & Reis, R. The stress hyperglycemia ratio as risk marker in acute heart failure patients. Rev. Port Cardiol. 42, 443–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2023.01.010 (2023).

Mi, D. et al. Stress hyperglycemia is associated with in-hospital mortality in patients with diabetes and acute ischemic stroke. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 28, 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13764 (2022).

Shen, C. L., Xia, N. G., Wang, H. & Zhang, W. L. Association of stress hyperglycemia ratio with Acute ischemic stroke outcomes post-thrombolysis. Front. Neurol. 12, 785428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.785428 (2021).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10, 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01899-x (2023).

Zhang, Z. Multiple imputation with multivariate imputation by chained equation (MICE) package. Ann. Transl Med. 4 https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.12.63 (2016).

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006 (2009).

Stevens, P. E. & Levin, A. Evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease: synopsis of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 clinical practice guideline. Ann. Intern. Med. 158, 825–830. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00007 (2013).

Umpierrez, G. E. et al. Hyperglycemia: an independent marker of in-hospital mortality in patients with undiagnosed diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 87, 978–982. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.87.3.8341 (2002).

Krinsley, J. S. Association between hyperglycemia and increased hospital mortality in a heterogeneous population of critically ill patients. Mayo Clin. Proc. 78, 1471–1478. https://doi.org/10.4065/78.12.1471 (2003).

Baker, E. H. et al. Hyperglycaemia is associated with poor outcomes in patients admitted to hospital with acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 61, 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2005.051029 (2006).

Capes, S. E., Hunt, D., Malmberg, K., Pathak, P. & Gerstein, H. C. Stress hyperglycemia and prognosis of stroke in nondiabetic and diabetic patients: a systematic overview. Stroke 32, 2426–2432. https://doi.org/10.1161/hs1001.096194 (2001).

Iglesias, P. et al. Fasting hyperglycaemia and in-hospital mortality in elderly population. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 65, 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02514.x (2011).

Barsheshet, A. et al. Admission blood glucose level and mortality among hospitalized nondiabetic patients with heart failure. Arch. Intern. Med. 166, 1613–1619. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.15.1613 (2006).

Capes, S. E., Hunt, D., Malmberg, K. & Gerstein, H. C. Stress hyperglycaemia and increased risk of death after myocardial infarction in patients with and without diabetes: a systematic overview. Lancet 355, 773–778. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(99)08415-9 (2000).

Vriesendorp, T. M., Morélis, Q. J., Devries, J. H., Legemate, D. A. & Hoekstra, J. B. Early post-operative glucose levels are an independent risk factor for infection after peripheral vascular surgery. A retrospective study. Eur. J. Vasc Endovasc Surg. 28, 520–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.08.006 (2004).

Gao, S. et al. Predictive value of the Acute-to-chronic glycemic ratio for In-Hospital outcomes in patients with ST-Segment Elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Angiology 71, 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003319719875632 (2020).

Marenzi, G. et al. Prognostic value of the Acute-to-chronic glycemic ratio at Admission in Acute myocardial infarction: a prospective study. Diabetes Care. 41, 847–853. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1732 (2018).

Kosiborod, M. et al. Admission glucose and mortality in elderly patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction: implications for patients with and without recognized diabetes. Circulation 111, 3078–3086. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.104.517839 (2005).

Planer, D. et al. Impact of hyperglycemia in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the HORIZONS-AMI trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 167, 2572–2579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.06.054 (2013).

Paolisso, P. et al. Hyperglycemia, inflammatory response and infarct size in obstructive acute myocardial infarction and MINOCA. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-021-01222-9 (2021).

Paolisso, P. et al. Impact of admission hyperglycemia on short and long-term prognosis in acute myocardial infarction: MINOCA versus MIOCA. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 192. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-021-01384-6 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Prognostic significance of the stress hyperglycemia ratio in critically ill patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 275. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-02005-0 (2023).

Sia, C. H. et al. Optimal glucose, HbA1c, glucose-HbA1c ratio and stress-hyperglycaemia ratio cut-off values for predicting 1-year mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic acute myocardial infarction patients. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-021-01395-3 (2021).

Xu, W. et al. Predictive value of the stress hyperglycemia ratio in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from a multi-center observational study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 21, 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-022-01479-8 (2022).

Zhang, C. et al. Relationship between stress hyperglycemia ratio and allcause mortality in critically ill patients: results from the MIMIC-IV database. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14, 1111026. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2023.1111026 (2023).

Worthley, M. I. et al. The deleterious effects of hyperglycemia on platelet function in diabetic patients with acute coronary syndromes mediation by superoxide production, resolution with intensive insulin administration. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 49, 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.053 (2007).

Ceriello, A. et al. Oscillating glucose is more deleterious to endothelial function and oxidative stress than mean glucose in normal and type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 57, 1349–1354. https://doi.org/10.2337/db08-0063 (2008).

Paolisso, P. et al. Impact of admission hyperglycemia on heart failure events and mortality in patients with Takotsubo Syndrome at Long-Term Follow-up: data from HIGH-GLUCOTAKO investigators. Diabetes Care. 44, 2158–2161. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-0433 (2021).

Gao, S., Huang, S., Lin, X., Xu, L. & Yu, M. Prognostic implications of stress hyperglycemia ratio in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary arteries. Ann. Med. 55, 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2186479 (2023).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

There was no project specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XFC, ZWY, RS, XYW and XHL contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by XFC, ZWY, RS, XYW. The first draft of the manuscript was written by XFC, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Yang, Z., Shi, R. et al. Stress hyperglycemia ratio association with all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease: an analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Sci Rep 14, 29110 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80763-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80763-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The prognostic significance of stress hyperglycemia ratio in evaluating all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk among individuals across stages 0–3 of cardiovascular–kidney–metabolic syndrome: evidence from two cohort studies

Cardiovascular Diabetology (2025)

-

Stress hyperglycemia ratio and incident hypertension in chinese middle-aged and older adults: mediating roles of lipids in a prospective cohort

Lipids in Health and Disease (2025)

-

Association between stress hyperglycemia ratio and neovascular glaucoma in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy

BMC Ophthalmology (2025)

-

Predictive performance of stress hyperglycemia ratio for poor prognosis in critically ill patients: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)

-

Dysglycaemia and the interaction of chronic and acute glycaemia with mortality post cardiac surgery

Scientific Reports (2025)