Abstract

Laser weld point detection is crucial in modern industrial manufacturing, yet it faces challenges such as a limited number of samples, uneven distribution, and diverse, irregular shapes. To address these issues, this paper proposes an innovative model, YOLO-Weld, which achieves lightweight design while enhancing detection accuracy. Firstly, a targeted data augmentation strategy is employed to increase both the quantity and diversity of samples from minority classes. Following this, a Diverse Class Normalization Loss (DCNLoss)function is designed to emphasize the importance of tail data in the model’s training. Secondly, the Adaptive Hierarchical Intersection over Union Loss (AHIoU Loss)function is introduced, which assigns varying levels of attention to different Intersections over Union (IoU) samples, with a particular focus on moderate IoU samples, thereby accelerating the bounding box regression process. Finally, a lightweight multi-scale feature processing module, MSBCSPELAN, is proposed to enhance multi-scale feature handling while reducing the number of model parameters. Experimental results indicate that YOLO-Weld significantly improves the accuracy and efficiency of laser weld point detection, with mean Average Precision at 50 (\(\:{mAP}_{50}\)) and mean Average Precision at 50:95 (\(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\)) increasing by 15.6% and 15.8%, respectively. Additionally, the model’s parameter count is reduced by 0.4 M, GFLOPS decreases by 1.1, precision improves by 4.3%, recall rises by 22.2%, and the F1 score increases by 15.1%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the realm of precision manufacturing, laser welding1 is widely embraced for its accuracy, efficiency, and dependability, particularly in sectors such as aerospace, automotive, and electronics. However, as its adoption grows, the challenge of inspecting laser welds for quality has become increasingly critical, affecting both product performance and safety. Unlike traditional PCB soldering, laser weld inspection is a more complex task, underscoring its significance and the need for prompt solutions.

During the welding process, key defects such as bulges(guBao), insufficient solder (xuHan), and breaks(duanLie) are prone to occur at laser weld points. These issues not only pose a serious threat to the safety and reliability of the products but may also lead to catastrophic consequences. These defects exhibit complex and varied forms, far surpassing issues such as shorts, spurs, and mouse bites2 typically found in traditional PCB solder joints. More importantly, there is a relative scarcity of detection algorithms specifically focused on laser weld points, with almost no relevant research similar to this study. This situation presents challenges that are distinctly different from those encountered with PCB solder joints, thereby increasing the level of difficulty.

In the realm of industrial detection, we are confronted with a host of unprecedented technical challenges. The most pressing issue is the severe imbalance of datasets. There is a vast disparity in the quantity of different types of welds, with some critical defect types having very few samples, leading to subpar model performance in recognizing these minority classes. The imbalance not only severely affects the overall performance and reliability of the detection system but may also lead to the complete neglect of certain hazardous defects. Secondly, traditional IoU loss functions struggle with the diverse and irregular shapes of laser welds3, such as the issue of uneven gradient changes which make it difficult for models to learn effectively, and they also fail to fully consider the shape and scale characteristics of bounding boxes4. These issues are particularly pronounced in the localization and identification of complex welds, leading to insufficient detection accuracy. Furthermore, the existing methods’ bounding boxes cannot adapt to sample characteristics, a rigid characteristic that greatly limits the model’s ability to handle welds of different shapes5. More challenging is the fact that laser welds exhibit a highly intricate and varied morphology, with defects presenting notable variations in shape, color, and luminosity. Traditional computer vision techniques often fall short when faced with such complex targets, prone to errors and omissions in detection. In the field of high-precision manufacturing, these unreliable results can lead to substandard products entering the market, potentially causing significant product liability disputes.

Given the pivotal role of laser weld detection technology in modern industrial manufacturing, coupled with the current inadequacy of research, developing an efficient and accurate detection algorithm for laser welds has become an urgent task. This study aims to meet the practical needs for such detection technology in industrial production, enhance the control over product quality, and reduce potential safety hazards. To tackle the aforementioned challenges, we have devised an innovative solution. Initially, we employ a targeted data augmentation strategy, enhancing minority class samples through random scaling, color, and brightness adjustments. We have crafted the DCNLoss function, integrating a sliding adjustment factor that modulates the contribution of boundary samples to the loss based on IoU values, incorporating a smoothing mitigation factor to lessen the impact of negative samples on tail classes, and utilizing a weight compensation factor to bolster the discriminative power for tail categories. Secondly, we have designed a novel regression loss function called AHIoU Loss, which introduces both nonlinear and linear growth components to handle samples with different IoU values, thereby increasing the emphasis on samples with medium IoU values. Additionally, we have incorporated a “Measure” section to focus on the shape and scale of the bounding boxes, enhancing localization accuracy through centroid calculations. Adaptive auxiliary bounding boxes adjust their scale based on sample characteristics, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization capabilities. Finally, drawing on the concept of MSBlock6, we have designed the MSBCSPELAN module, employing a hierarchical feature fusion strategy and a heterogeneous kernel selection protocol. Utilizing convolutional kernels of varying sizes to process multi-scale features at different network stages, we enhance detection performance while reducing the number of parameters through parallel sub-network processing and fusion. The main contributions of this paper are:

-

(1)

We propose a targeted data augmentation strategy and the DCNLoss function, aimed at mitigating the long-tail effect and enhancing the accuracy of minority class identification.

-

(2)

We have designed the AHIoU Loss function to optimize the processing of samples with varying IoU values, thereby enhancing the precision and stability of regression.

-

(3)

We propose the MSBCSPELAN module, which enhances detection accuracy through multi-scale feature processing while also reducing the number of parameters.

-

(4)

Developing an efficient algorithm specifically for laser weld detection, optimizing the particular challenges faced during the laser weld detection process.

Related work

Solder joint defect detection

In the realms of electronics manufacturing and quality control, there has been significant progress in solder joint defect detection technology in recent years, with the application of deep learning techniques greatly enhancing the performance and efficiency of detection. A variety of innovative models and methods have emerged, continually advancing the development of detection technology. The Efficient Faster R-CNN7, optimized by EfficientNet-B7 for feature extraction, employs a generalized intersection-over-union loss function, thereby enhancing detection accuracy. Additionally, a method combining laser thermography with Mask R-CNN has been effective for the efficient detection and quantification of cracks8. An enhanced Faster R-CNN model, integrating FPN and SPAM, utilizes data augmentation to boost detection robustness9. The combination of YOLOv5 with a laser scanning system demonstrates the potential for efficient detection of weld surface defects10. The LF-YOLO11 model integrates multi-scale features with efficient feature extraction, achieving a balance between performance and resource consumption. The Yolo-MSAPF12 model, through multi-scale fusion and feature filtering, significantly enhances detection effectiveness. Furthermore, a context- and scale-aware YOLO model further improves detection accuracy13.

Methods for addressing the long-tail effect

The long-tail effect is a critical challenge in computer vision, and significant advancements have been made in this area through a variety of innovative technologies. The Seesaw Loss14 optimizes detection performance for tail class objects through dynamic gradient rebalancing. The Equalization Loss v215 enhances the detection of rare classes by introducing a gradient-guided reweighting mechanism. The Adaptive Class Suppression Loss16 enhances the discernment of tail classes by adaptively adjusting suppression gradients. The adversarial training that combines balanced Softmax loss and data augmentation further bolsters the model’s robustness17. Class balance training mitigates recognition bias by refining the structure of the dataset18. Distribution alignment techniques19 and the LiVT20 method enhance the efficiency of semi-supervised learning by streamlining the sampling process. The Slide Loss21 and C2AM Loss22 have independently improved the accuracy of sample detection by utilizing Intersection over Union (IoU) values and adaptive angular boundaries, respectively.

Bounding box regression

Bounding box regression techniques continue to advance in the fields of object detection and instance segmentation, primarily through innovations and refinements in loss functions. The GIoU23 addresses the optimization issue of non-overlapping bounding boxes. The DIoU24 and CIoU25 further enhance the regression accuracy by introducing factors such as distance and aspect ratio. The Focal and EIoU loss26 focuses on high-quality anchor boxes, improving convergence speed and localization accuracy. The SIoU loss27 enhances training effectiveness by considering angular factors. The Inner-IoU Loss5 accelerates the regression process by utilizing auxiliary bounding boxes. The MPDIoU Loss28 simplifies the computation and enhances the precision of similarity comparison. The Shape-IoU loss4 focuses on the shape and scale of bounding boxes, enhancing the accuracy of regression. The Focaler-IoU loss29, by concentrating on various regression samples, improves the performance of the detector.

Multi-scale feature processing

Multi-scale feature processing is essential for object detection, and there have been many innovative network structures and algorithms in this area in recent years. The FPN30 enhances detection performance by constructing high-level semantic feature maps. PANet31 improves information flow and localization accuracy through a bottom-up path enhancement. CSPNet32 reduces computational load by eliminating redundant gradient information. YOLOv7 achieves a dual enhancement in speed and accuracy through flexible training utilities and a composite scaling approach33. YOLO-MS6 bolsters multi-scale feature representation by examining the impact of various convolutional kernel sizes. RTMDet34 enhances model efficiency and accuracy through dynamic label assignment. The network design strategy based on gradient path analysis optimizes the model’s expressive power35.

Methodology

YOLOv9 algorithm review

YOLOv936 enhances the accuracy and efficiency of object detection through two core innovations: Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) and the Generalized Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (GELAN). The Programmable Gradient Information (PGI) addresses the issue of information loss in deep learning networks during feature extraction and spatial transformation. By generating reliable gradient information through auxiliary reversible branches, it ensures that key attributes of deep features are preserved, enhancing the model’s training effectiveness and accuracy. GELAN expands upon the Efficient Layer Aggregation Network (ELAN), optimizing the number of parameters, computational complexity, accuracy, and inference speed. It maximizes parameter utilization and information retention through gradient path planning. Combining these two innovations, YOLOv9 significantly enhances the performance and robustness of object detection tasks while maintaining efficient computation. It has emerged as a leading algorithm in the field of object detection, suitable for models of various scales and different inference devices. The model architecture of YOLOv9 is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Expansion of minority class samples and class balance

Targeted data augmentation

In this study, to address the issue of class imbalance in the laser welding spot image dataset, we employed the copy-and-paste data augmentation method. The dataset comprises ten categories of welding spots, with the “good” category having the highest sample count, exceeding 2,500. In contrast, the categories of Missing Solder Joint(shaoHanDian), Inclination(jiaJiao), and Burnt(shaoJiao) have very few samples, with only a handful available, resulting in a highly uneven class distribution, as illustrated in Fig. 2a.To address this situation, we performed data augmentation on the welding spot images, excluding the “good” category. Specifically, we increased the sample count by copying images from the minority categories and pasting them at random positions. Before pasting, these images underwent random scaling, color adjustments, and brightness modifications to enhance their diversity, while ensuring that the pasted images did not overlap with the original positions. This method effectively increased the sample count of the minority categories while keeping the sample count of the “good” category unchanged. Figure 2b shows the class distribution after data augmentation. While the sample counts for categories other than “good” have significantly increased, the long-tail effect still persists. Figure 3 displays the augmented image forms, where the three original welding spots on the left and right welding plates are shown, while the welding spots within the other green boxes are the augmented images. Although this data augmentation method did not fully resolve the class imbalance issue, it did enhance the quantity and diversity of samples in the minority categories, thereby improving the model’s recognition capability.

Long-tail effect loss

To address the long-tail effect caused by class imbalance, we designed a new loss function called Diverse Class Normalization Loss (DCNLoss). This loss function consists of three distinct factors: the sliding adjustment factor, the smoothing mitigation factor, and the weight compensation factor. Through the interaction of these three factors, the contribution of each sample to the overall loss can be adjusted, enhancing the classification model’s focus on minority categories and improving its recognition accuracy for tail-end category samples. The final loss function \(\:{L}_{Dcn}\) is defined as follows:

Here, N represents the number of samples in a batch, while n denotes the number of classes, \(\:{y}_{k}^{i}\) is the one-hot encoding of the target class for the i-th sample, \(\:{p}_{k}^{i}\) is the predicted probability for the i-th sample.

The sliding adjustment factor \(\:{M}_{\mu\:}^{{x}_{i}}\) is designed to modulate each sample’s contribution to the loss based on the Intersection over Union (IoU) value. By adaptively learning the threshold parameter µ, we classify samples with an IoU value below µ as negative samples and those exceeding µ as positive samples. However, samples that are situated near the threshold µ are often difficult to classify clearly due to the boundary characteristics of their IoU values. This ambiguity can lead to misclassifications, consequently adversely affecting the training of the model. To enhance the model’s performance and robustness, we more effectively utilize these “boundary” samples by assigning them greater weights, thereby bolstering the model’s learning capacity. Specifically, by assigning higher weights to samples near the threshold µ, we can significantly increase the relative loss of these hard-to-classify samples. This approach guides the model to focus more attention on those misclassified instances that are challenging to categorize correctly. Enhancing the model’s ability to handle boundary cases helps to extract more information from the training data, ultimately improving the overall performance and generalization ability of the model. Its definition is as follows:

In this context, δ is a small constant (set to 0.1 in this study) that is used to fine-tune the IoU threshold and define the range of boundary samples. The parameters \(\:{k}_{1}\) and \(\:{k}_{2}\) are employed to control the weight ratio between boundary samples and absolute positive samples, with their total summing to 1. In this paper, we set the ratio \(\:{k}_{1}:{k}_{2}=0.6:0.4\).

The design of the smoothing mitigation factor \(\:{M}_{{t}_{i}}\) aims to address the issue of class imbalance. During the training process, the abundance of samples from head categories significantly impacts the model’s loss and gradient contributions. In contrast, samples from tail categories are scarce, making it challenging to obtain sufficient gradient signals for effective learning. This imbalance results in poor performance of the model on tail categories and inadequate feature learning capabilities. During training, tail categories often suffer from a scarcity of positive samples, resulting in their gradients being dominated by negative samples. This further hinders the effective learning of features associated with tail categories. To address this issue, we introduce the smoothing mitigation factor \(\:{M}_{{t}_{i}}\), which dynamically adjusts the influence of negative samples on the gradients for tail categories, thereby reducing their dominant effect. When the number of tail category samples \(\:{N}_{{t}_{i}}\) is relatively small, the value of \(\:{M}_{{t}_{i}}\) is correspondingly low. This smaller smoothing mitigation factor reduces the impact of negative samples, indirectly enhancing the tail category’s learning from positive samples. As a result, the model can focus more attention on the limited positive samples, thereby improving its learning effectiveness for tail categories. The expression for the smoothing mitigation factor is as follows:

In this context, ε is a small positive number used to prevent division by zero. \(\:{t}_{i}\) denotes the true class label of sample \(\:i\), which indicates the actual category to which sample \(\:i\) belongs. \(\:{N}_{{t}_{i}}\) represents the number of samples in category \(\:{t}_{i}\), while \(\:{N}_{max}\) is the sample count for the most frequently occurring class.

By introducing the smoothing mitigation factor, we can effectively balance the gradient contributions across different classes, allowing the model to focus more on tail categories while alleviating the suppressive effect of negative samples from head categories. During the training process, the smoothing mitigation factor helps to prevent minority classes from being dominated by majority classes, thereby enhancing the feature learning capabilities and recognition performance for tail categories.

To enhance the classification capability of tail categories, DCNLoss introduces an additional loss penalty for misclassifying tail category samples as head category samples. Through a weight compensation factor, the model’s ability to distinguish these samples is strengthened, enabling better recognition and classification of tail category samples during the training process. The weight compensation factor \(\:{C}_{{t}_{i}}\) serves to adjust the logit differences, enhancing the model’s ability to handle prediction uncertainty, particularly by amplifying the logits differences for tail categories. This adjustment improves the model’s discrimination ability for these categories, allowing it to better distinguish between them during classification.

\(\:{x}_{{t}_{i}}\) represents the logit value of the sample for its true class \(\:{t}_{i}\), while \(\:{\:x}_{j}\)denotes the predicted logit value of sample \(\:i\) for a non-target class \(\:j\).In this context, \(\:{j\ne\:t}_{i}\) indicates that \(\:j\) represents any category other than the true class \(\:{t}_{i}\) of sample \(\:i\). The term \(\:{max}_{{j\ne\:t}_{i}}{\:x}_{j}\) denotes the highest logit value among all non-true categories for the sample. The expression \(\:{x}_{{t}_{i}}-{max}_{{j\ne\:t}_{i}}{\:x}_{j}\) reflects the model’s confidence difference between the correct category and the most likely incorrect category. This difference provides insight into the model’s decision-making confidence when differentiating among various classes. When this difference is substantial, it indicates that the model’s prediction for the correct category is relatively confident. In such cases, the weight compensation factor employs a logarithmic function to reduce this difference, thereby preventing the model from becoming overly confident, which could lead to gradient exploding issues. Conversely, when this difference is small, it suggests that the model has a high level of uncertainty regarding its prediction for the current sample. In this scenario, the weight compensation factor will amplify this difference, providing the model with more corrective signals to improve its classification accuracy.

Optimizing bounding box regression with comprehensive geometric information

In object detection tasks, the accuracy of boundary box regression directly affects the quality of the detection results. While traditional IoU loss functions are simple and effective, they have certain limitations when handling laser welding spots due to the diversity in shape, scale, and difficulty of the samples. To address these issues, we propose a new regression loss function called Adaptive Hierarchical Intersection over Union Loss(AHIoU Loss), designed to better suit laser welding spot detection and enhance the overall performance of boundary box regression.

First, in boundary box regression, samples within different IoU value ranges contribute unevenly to the model. To address this issue, we focus on samples with moderate IoU values and discard difficult samples with IoU values below a threshold d, setting their outputs to 0. This ensures they do not affect loss computation or participate in gradient updates. Traditional IoU loss functions exhibit excessive gradient fluctuations when handling low IoU values, leading to training instability. Conversely, when dealing with high IoU values, the gradient signal is insufficient, making it difficult to finely adjust the boundary boxes. To address this, we introduce nonlinear and linear growth components to handle low and high IoU value samples, respectively. The nonlinear growth component provides a gradual increase in loss for low IoU value ranges, preventing excessive gradient fluctuations and ensuring training stability. Meanwhile, the linear growth component offers a smooth gradient signal for high IoU value ranges, facilitating fine-tuning of boundary boxes. This design makes the loss function more sensitive in the moderate IoU value range, thereby enhancing the model’s overall regression performance.

where \(\:\text{d},\:\)σ represent the specified lower and upper limits, respectively.

Secondly, traditional boundary box regression methods typically focus solely on the geometric relationship between the ground truth box and the predicted box, primarily relying on geometric metrics such as IoU to determine the regression loss. However, these methods largely overlook the variations in the shape and scale of the bounding boxes, which are crucial for enhancing the accuracy of regression. To address this shortcoming, we propose a novel “Measure” design that incorporates the differences in bounding box shapes, as well as the displacement between the centroid and the center of the bounding box, into the loss calculation. This approach provides a more comprehensive representation of the morphological discrepancies between the ground truth and predicted boxes.

We applied the Segment Anything Model (SAM)37 to preprocess the input images. As a versatile image segmentation model, SAM can automatically generate segmentation masks for target areas, which is particularly crucial for solder joint detection tasks, as illustrated in (a) and (c) of Fig. 4, these represent the true shapes of the laser weld spots. In the images processed with masks, we generated bounding boxes for each solder joint and analyzed their shape characteristics by calculating the centroids of the target objects. The red dots indicate the center positions of the bounding boxes, while the green dots represent the centroids of the target objects, as shown in (b) and (d) of Fig. 4. Upon observation, we found that when the shape of the solder joint is close to circular, the geometric center of the bounding box nearly coincides with the centroid. In contrast, for irregularly shaped solder joints, there is a significant displacement between the two. As the centroid accurately reflects the distribution of the shape, it provides more precise localization information compared to the simple center of the bounding box. Therefore, incorporating the centroid into the design of the regression loss can enhance the localization accuracy of the targets.

To better capture the shape differences of the bounding boxes, we quantified the geometric differences between the predicted boxes and the ground truth boxes using a series of formulas. First, to account for the impact of the bounding box shape on the loss computation, we use Formula (6) and (7) to adjust the coefficients for the width and height, respectively.

Here, \(\:{w}^{gt}\) and \(\:{h}^{gt}\) represent the width and height of the ground truth box, respectively. The variable scale is a scaling factor related to the size of the target in the dataset, while \(\:ww\) and \(\:\:hh\) are the weight coefficients in the horizontal and vertical directions, respectively, and their values are related to the shape of the ground truth box.

Next, we use Formula (8) to quantify the distance between the centers of the candidate box and the ground truth box, which allows us to adjust the shape and size of the bounding boxes.

In this context, the diagonal length of the smallest enclosing bounding box is denoted as c, while \(\:\left({x}_{c},{y}_{c}\right)\) and \(\:\left({x}_{c}^{gt},{y}_{c}^{gt}\right)\) indicate the coordinates of the centers of the candidate box and the ground truth box, respectively.

Additionally, we introduce the calculation of the centroid position. By using Formula (9), we incorporate the distance between the center position of the predicted box and the centroid position into the loss function. This design can capture more subtle shape and position differences, thereby improving the regression accuracy of the bounding boxes. \(\:\left({x}_{ctr},{x}_{ctr}\right)\) represents the centroid coordinates of the target object.

At the same time, to make the shape differences of the bounding boxes more prominent in the loss computation, we designed a shape-related penalty term. By using Formula (10), we measure the shape differences of the bounding boxes across different dimensions. By adjusting the parameter θ of the penalty term, we can flexibly control the impact of shape differences on the regression loss. Finally, we also dynamically adjust the width and height through Formula (11).

Based on the above design, we define a new bounding box regression loss function \(\:{L}_{\text{M}\text{e}\text{a}\text{s}\text{u}\text{r}\text{e}}\), which organically integrates the traditional IoU loss with the distance and shape adjustment terms.

To further enhance the adaptability of the regression method, we introduce an adaptive auxiliary bounding box mechanism into the regression framework. The traditional IoU loss exhibits inconsistent gradient changes across different IoU intervals, making it unable to adaptively adjust based on the distinct characteristics of the samples. To address this issue, the adaptive auxiliary bounding box component dynamically adjusts the scale of the bounding boxes based on the different IoU levels of the samples. For high IoU samples, smaller auxiliary bounding boxes are used for loss calculation to accelerate convergence; for low IoU samples, larger auxiliary bounding boxes are used to enhance regression speed. In the specific calculations, \(\:\left({{b}_{l}^{gt},b}_{r}^{gt},{b}_{t}^{gt},{b}_{b}^{gt}\right)\) represents the boundary position of the ground truth box, and \(\:\left({b}_{l},{b}_{r},{b}_{t},{b}_{b}\right)\) represents the boundary of the auxiliary bounding box. The area of intersection is calculated as the product of the intersection lengths in the horizontal and vertical directions:

The area of the union takes into account both the areas of the ground truth box and the auxiliary detection box, as well as a scaling factor ratio:

The IoU of the adaptive auxiliary box is defined as follows:

The final regression loss integrates several components, including shape adjustments for the bounding box, traditional IoU, and the IoU of the auxiliary box, and is defined as follows:

Optimisation of multi-scale feature processing

In YOLOv9, the RepNCSPELAN4 module serves as a feature extraction and fusion component, incorporating the characteristics of CSPNet and ELAN. Its primary aim is to enhance the model’s lightweight nature, inference speed, and accuracy. Although this module has its strengths in these areas, it still falls short when it comes to handling multi-scale features. Firstly, the feature integration is not as comprehensive as it could be. Even though there is channel splitting and parallel processing, there is room for improvement in the merging of features across different scales. Secondly, the size of the single convolutional kernel limits the ability to capture features, with a focus primarily on 3 × 3 kernels, which are insufficient for capturing features at various scales. To address the aforementioned shortcomings, we have integrated the concept of the MSBlock module into the RepNCSPELAN4 module, devising a novel lightweight multi-scale feature processing module, dubbed MSBCSPELAN. This new module has been employed to replace the original RepNCSPELAN4 module in YOLOv9.

The MSBCSPELAN module is engineered to enhance the multi-scale feature representation in real-time object detection. It employs a tiered feature fusion strategy coupled with a heterogeneous convolution kernel selection protocol, effectively handling features at varying scales across different stages of the network. The design of the module segments the input into several branches, each dealing with a distinct subset of features. It employs 1 × 1 convolutions for feature transformation, followed by depthwise separable convolutions, and then another round of 1 × 1 convolutions to enhance the features and reduce the number of parameters. The MSBCSPELAN module utilizes convolution kernels of varying sizes – including 9 × 9, 7 × 7, 5 × 5, and 3 × 3 – to capture image features at different scales. This strategic implementation allows for the detection of intricate details and small object features at lower levels, while larger area characteristics are captured at higher levels, subsequently enhancing the model’s ability to recognize larger targets. Ultimately, the features are further integrated, enabling the detector to more effectively recognize and handle targets of varying sizes, and significantly enhancing the network’s capability to capture multi-scale features. The architecture of the MSBCSPELAN module is depicted in Fig. 5.

With the integration of the MSBCSPELAN module, there is a significant enhancement in the detector’s ability to identify and process targets of varying sizes. The module’s hierarchical feature fusion strategy effectively amalgamates features from different scale targets, enriching the feature representation. Moreover, in terms of multi-scale feature extraction capabilities, the MSBCSPELAN leverages heterogeneous convolution kernel selection, employing kernels of different sizes at various stages of the network. This approach notably bolsters the model’s capacity to handle targets of different scales.

The introduction of the MSBCSPELAN module has led to a refined feature fusion process, where its hierarchical feature fusion strategy successfully integrates features from targets at different scales, thereby enhancing the richness of feature representation. In terms of multi-scale feature extraction capabilities, the MSBCSPELAN module stands out by employing a selection of heterogeneous convolution kernels. It utilizes convolution kernels of varying sizes at different stages of the network, which significantly enhances the model’s ability to process targets of diverse scales. Furthermore, the MSBCSPELAN module adopts a lightweight design, which not only maintains efficient feature processing capabilities but also reduces computational overhead.

Experiments

Dataset

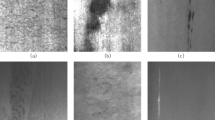

In this study, we collected a dataset of laser weld point images sourced from real industrial scenarios. Each image features three weld points on each side, totaling six laser weld points. To effectively assess the quality of the welds, personnel from the technical department classified the laser weld points into ten distinct types based on their varying characteristics, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Table 1 presents the classification criteria and characteristics for the different categories.

Due to the dataset being sourced from a real industrial setting, the number of samples is relatively limited, comprising only 1,082 images. In machine learning model training, an insufficient number of samples can negatively impact the model’s generalization and performance. To effectively train and evaluate the model on this limited dataset, we divided it into a ratio of 7:2:1, with 70% for training, 20% for validation, and 10% for testing. The selection of 70% of the data for training ensures that the model acquires a sufficient number of samples to capture the key characteristics present in the data during the learning phase. The 20% validation set is used for model tuning during the training process, which is particularly beneficial in the case of small datasets, as it aids in early stopping to prevent overfitting. Although the test set comprises only 10% of the dataset, consisting of approximately 108 images, it contains around 648 weld points. This quantity is sufficient to provide the model with a reasonable sample size, ensuring that reliable measurements and validations of the model’s performance can be conducted during the evaluation phase. Figure 7 illustrates the data distribution within the training dataset, along with detailed label information.

Experimental setup and evaluation metrics

The performance of the model was evaluated on a machine equipped with four NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPUs, each with 11GB of RAM. The processor is an Intel® Xeon® CPU E5-2680 v4 running at 2.40 GHz. The experiment was conducted on a Linux system using Python 3.8 and Torch 2.1.0. The epoch was set to 500, the batch size was 12, and the input images had a resolution of 640 × 640 pixels.

For the detection of laser weld spots, we evaluate the effectiveness of the algorithm using metrics such as precision, recall, mean Average Precision (mAP), and the F1 score. The mAP is the average AP value across different types of laser weld spots, defined as follows.

Here, N represents the number of types of laser weld spots, and AP is the area under the Precision-Recall (PR) curve, calculated using the formula shown in the equation

P denotes precision, which represents the probability that a predicted positive sample has been correctly classified, and it is calculated according to the formula provided in the equation. Here, precision is defined as the ratio of correctly predicted positive instances to all instances that the model has labelled as positive, indicating its accuracy in identifying the number of positive samples. TP refers to the number of true positive samples that were correctly identified, while FP refers to the number of false positive samples that were incorrectly labelled as positive.

R denotes recall, which measures the proportion of actual positive samples that the model has correctly identified. FN refers to the number of positive samples that have been incorrectly classified as negative.

The F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, assessing the overall accuracy and completeness of the model.

These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s performance in detecting and classifying laser welding spots, ensuring its robustness and reliability in practical applications.

Results analysis

Parameter analysis of the sliding adjustment factor

To determine the optimal parameters for the sliding factor, we conducted experiments using YOLO-Weld on the laser welding dataset, with the results presented in Table 2. By adjusting the threshold parameter δ and exploring various combinations of the weight factors \(\:{k}_{1}\) and \(\:{k}_{2}\), we optimised the parameter settings for the sliding adjustment factor \(\:{M}_{\mu\:}^{{x}_{i}}\), enhancing the model’s performance in classifying boundary samples between positive and negative categories.

As a key parameter for controlling difficult-to-classify samples, the value of δ directly affects the model’s sensitivity to boundary information. Experiments demonstrated that when \(\delta=0.1\), the model achieved optimal performance across all core metrics, particularly in Recall, F1 score, \(\:{mAP}_{50}\), and \(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\), reaching an ideal balance. While a smaller δ refines the distinction between boundary samples and absolute positive samples, the lack of significant differentiation can result in the model underperforming in learning the features of boundary samples. This effect is particularly pronounced in complex scenarios, leading to inadequate recognition of boundary samples. Conversely, when δ is increased to 0.12, the differences between boundary and absolute positive samples are overly accentuated. This excessive penalisation of boundary samples causes the model to overlook some critical features of absolute positive samples, ultimately resulting in a decline in overall performance.

Building on this, \(\:{k}_{1}\)and \(\:{k}_{2}\) regulate the weight allocation for boundary samples and absolute positive samples within the loss function. An increase in the value of \(\:{k}_{1}\) indicates that the model is placing greater emphasis on boundary samples, whereas an increase in \(\:{k}_{2}\) suggests that the model is more inclined to learn the features of absolute positive samples. Through experiments, it was found that when \(\delta=0.1\) and the ratio \(\:{k}_{1}:{k}_{2}=0.6:0.4\), the model achieved optimal results in key metrics such as F1 score, \(\:{mAP}_{50}\), and \(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\). This indicates that moderately increasing the weight of boundary samples helps the model more accurately capture the features of complex boundary samples, thereby improving overall detection accuracy. The combination of \(\:{k}_{1}:{k}_{2}=0.4:0.6\) demonstrates a high level of accuracy. However, due to its strong emphasis on absolute positive samples, the model pays insufficient attention to the weighting of boundary samples. This results in a deficiency in handling complex boundary cases, leading to relatively weaker generalisation capabilities. Further experiments indicate that when the ratio of k1 is significantly unbalanced (for example, \(\:{k}_{1}:{k}_{2}=0.8:0.2\) or \(\:{k}_{1}:{k}_{2}=0.2:0.8\)), the model’s performance deteriorates noticeably. This decline results from an excessive focus on learning from one class of samples, which prevents the model from achieving an appropriate balance between boundary samples and absolute positive samples.

Ablation experiments

To evaluate the impact of the targeted data augmentation strategy, DCNLoss loss function, AHIoU Loss regression loss function, and the MSBCSPELAN multi-scale feature processing module on the YOLOv9 model, we conducted ablation experiments using the laser welding point dataset. The detailed experimental results can be found in Table 3.

Model_1 serves as the baseline model, employing only YOLOv9 and providing a reference for basic performance. Building on this, Model_2 incorporates a targeted data augmentation strategy that enhances the diversity of minority class samples through techniques such as duplication, random pasting, scaling, and brightness adjustment, thereby improving the model’s generalization capability. Model_3 introduces DCNLoss, optimizing sample contributions through sliding adjustments, smoothing mitigations, and weight compensation, which significantly enhances the recognition accuracy of minority classes. Model_4 adds AHIoU Loss, focusing on samples with moderate IoU values and considering the shapes of bounding boxes and centroid shifts, thereby improving both regression precision and stability. Model_5 introduces the MSBCSPELAN multi-scale feature processing module, which utilizes hierarchical feature fusion and heterogeneous convolutional kernels to enhance the model’s detection capability for targets of varying scales.

Model_6 combines Model_2 with DCNLoss to leverage diverse training samples for optimizing loss calculations, thereby further improving the recognition ability for minority classes. Model_7 builds upon Model_2 by incorporating AHIoU Loss, allowing the augmented data to provide diverse targets for bounding box regression, which enhances localization accuracy. Lastly, Model_8 merges Model_2 with MSBCSPELAN, resulting in a richer input that significantly boosts the model’s detection capabilities across various target scales.

Model_9 combines Model_6 with AHIoU Loss to optimize both classification and regression losses, enhancing the accuracy of minority class recognition and bounding box localization. Model_10 builds on Model_6 by introducing MSBCSPELAN, which improves the model’s handling of complex scenes while maintaining high sensitivity towards minority classes. Finally, Model_11 integrates Model_7 with MSBCSPELAN, optimizing bounding box regression and multi-scale feature extraction, achieving outstanding performance in detecting targets of various scales and shapes. Finally, Model_12 is the YOLO-Weld model, built on Model_9 and incorporating MSBCSPELAN. It integrates all the improvement methods with the aim of achieving optimal performance in laser welding point detection. Figure 8 displays the results of the 12 different models on \(\:{mAP}_{50}\), while Fig. 9 presents the \(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\) results for these different models.

In the industrial application of laser welding point detection, the complex and imbalanced dataset places high demands on the model’s robustness and generalization ability. The baseline model (Model_1) achieved an accuracy of 79.3%; however, its recall rate was only 56.1%. The \(\:{mAP}_{50}\) was 69.2%, while \(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\) was 49.5%. These results indicate that the model falls short in overall detection capability and does not meet the industrial requirements for high precision and high recall. The introduction of data augmentation in Model_2 resulted in significant improvements, with the recall rate rising from 56.1% to 67.0%, and the F1 score increasing from 65.7% to 71.5%. Additionally, \(\:{mAP}_{50}\) improved from 69.2% to 74.9%. These results indicate that data augmentation effectively alleviates the data imbalance issue, particularly enhancing the detection capability for minority classes, which is crucial for small sample detection in industrial scenarios.

However, despite the incorporation of DCNLoss, AHIoU Loss, and the MSBCSPELAN module in Models 3 to 5, the performance improvements were limited without the integration of data augmentation. DCNLoss did not fully leverage its potential in addressing the long-tail effect, highlighting the limitations of a single optimization approach in complex datasets.

Model_6, which integrates data augmentation and DCNLoss, achieved an accuracy of 86.5%, with the recall rate improving to 73.2%. The \(\:{mAP}_{50}\) reached 80.5%, and \(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\) was 61.4%.This improvement underscores the importance of integrating multiple strategies to enhance model performance in challenging scenarios. This demonstrates that data augmentation provides strong support for DCNLoss, particularly showing significant effectiveness in minority class detection tasks. It validates the effectiveness of combining data preprocessing with loss function optimisation.

In the combination experiments from Model_7 to Model_9, although the accuracy of Model_9 (81.9%) is slightly lower than that of Model_8 (82.0%), Model_9 outperformed in other key metrics. This indicates that Model_9 achieves a better fusion and synergistic effect in tackling data imbalance and optimizing bounding box regression, showcasing a robust generalization capability, especially in the complex task of weld point detection. Despite the slight decrease in accuracy, this minor loss can be regarded as a reasonable trade-off for the significant enhancement in overall detection performance. Ultimately, the integrated model (Model_12) combines all optimization modules, including data augmentation, DCNLoss, AHIoU Loss, and MSBCSPELAN. It achieved an accuracy of 83.6%, with a recall rate of 78.3%, an F1 score of 80.8%, and \(\:{mAP}_{50}\) and \(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\) reaching 84.8% and 65.3%, respectively. This comprehensive approach underscores the model’s effectiveness in addressing the challenges of laser welding point detection in complex industrial environments. These results indicate that the collaboration of various modules enhanced the overall performance of the model, particularly better meeting the demands for efficient and precise weld point detection in industrial applications. Furthermore, with the inclusion of the multi-scale feature processing module MSBCSPELAN, the parameter count was reduced to 31.0 M, and GFLOPS decreased to 117.1, achieving a balance between lightweight design and high accuracy. This optimization facilitates the deployment of the model in real-world industrial settings where both efficiency and performance are crucial.

Comparative experiments

To validate the advantages of the YOLO-Weld network model, we conducted a comprehensive comparison with various mainstream methods on the laser weld dataset. The experimental results are detailed in Table 4, while Fig. 10 presents a comparison of the \(\:{mAP}_{50}\) across different models. This study demonstrates that the YOLO-Weld model exhibits outstanding performance in laser weld detection tasks, achieving significant improvements across multiple key metrics.

In terms of accuracy, YOLO-Weld significantly outperforms all other models with a score of 83.6%, surpassing the closest competitor, YOLOV9, by 4.3% points (79.3%). Additionally, the P values for YOLOX-x and YOLOV10-x are 72.1% and 71.1%, respectively, further underscoring the remarkable advantage of YOLO-Weld in reducing false positives.

In terms of recall (R), YOLO-Weld’s score of 78.3% significantly exceeds that of the second-place model, YOLOV8-l, which stands at 61.0%, representing an impressive improvement of 17.3% points. This clearly reflects the model’s substantial progress in reducing both false positives and false negatives. The F1 score, as the harmonic mean of precision and recall, is equally noteworthy; YOLO-Weld achieves 80.9%, far surpassing the second-best model, YOLOV3, which has a score of 66.0%, leading by nearly 15% points. This significant gap not only highlights the comprehensive improvement in the detection performance of YOLO-Weld but also confirms its achievement of a perfect balance between precision and recall.

In key evaluation metrics, YOLO-Weld also excels, achieving a \(\:{mAP}_{50}\) of 84.8%, which is 15.6% points higher than YOLOV9’s score of 69.2%. Additionally, the\(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\) score is 65.3%, reflecting an improvement of 15.8% points compared to YOLOV9’s 49.5%. These results indicate that YOLO-Weld maintains excellent detection performance across various IoU thresholds, particularly in comparison to YOLOV10-l (60.4%) and YOLOV6-l (60.5%), where the performance gap is even more pronounced.

It is noteworthy that while improving performance, YOLO-Weld has reduced its parameter count (31.0 M) and computational load (117.1 GFLOPS) compared to YOLOV9, being only slightly higher than YOLOV9-c. Although YOLOV9-c has a slight advantage in this regard, its performance is significantly inferior to that of YOLOV9. This demonstrates that we have carefully considered computational efficiency while optimizing model performance, allowing YOLO-Weld to have strong application potential for real-time detection in industrial settings, particularly on resource-constrained edge devices.

In summary, YOLO-Weld excels in key metrics such as precision, recall, F1 score, and mAP, while maintaining a relatively lightweight structure with low parameter count and computational complexity. This makes it not only suitable for industrial-grade applications but also capable of running efficiently in environments with limited computational resources, particularly in the context of laser weld point detection, which involves complex and imbalanced datasets.

Visualization results

Figure 11 illustrates the detection performance of both the YOLOv9 and YOLO-Weld algorithms across various samples. It is evident that YOLO-Weld outperforms YOLOv9 in terms of detection accuracy, while also significantly reducing instances of missed detections and false positives.In the top left panel, YOLOv9 incorrectly classified the ShuangLuoXuan class as the Good class. In the top right panel, it missed detecting the ShaoHanDian class altogether.In the bottom left panel, the WuNengLiang class was mistakenly identified as the DuanLie class. In the bottom right panel, the WuNengLiang class was incorrectly classified as the HanChuan class.In comparison, YOLO-Weld demonstrates greater precision on these samples, accurately identifying and classifying them while significantly reducing the likelihood of missed detections and false positives. This indicates that YOLO-Weld exhibits higher robustness and accuracy when handling complex samples.

Conclusion

Through this study, we propose a laser weld spot detection algorithm based on YOLO-Weld, addressing several challenges such as limited sample size, the long-tail effect caused by sample imbalance, errors in bounding box localization, slow regression processes, and the diverse shapes and inconsistent scales of samples in laser weld spot detection. Our solution includes the use of data augmentation strategies, which significantly increase the number of samples from minority classes. The DCNLoss loss function effectively mitigates the negative impact of the long-tail effect, while the AHIoU Loss function enhances the accuracy and stability of bounding box regression. By employing hierarchical feature fusion and selecting heterogeneous convolutional kernels, the lightweight multi-scale feature processing module MSBCSPELAN enhances the model’s capability to process image features at various scales. Simultaneously, it reduces both the number of parameters and the computational load of the model. The experimental results indicate that YOLO-Weld significantly improves the accuracy and efficiency of laser weld spot detection compared to existing methods, with enhancements of 15.6% and 15.8% in metrics \(\:{mAP}_{50}\)and \(\:{mAP}_{50:95}\), respectively. Additionally, the model’s parameter count is reduced by 0.4 M, and GFLOPS are decreased by 1.1. Furthermore, there are increases of 4.3% in precision, 22.2% in recall, and 15.1% in the F1 score. Consequently, YOLO-Weld presents an excellent solution for practical laser weld spot detection systems.

Nevertheless, we have yet to address all potential sources of interference, such as complex backgrounds, variations in lighting, and noise, all of which can still impact the detection accuracy of the model. Moreover, annotating a large number of data samples for laser weld spot detection is a task that is both time-consuming and costly. Future research could explore weakly supervised learning methods, such as leveraging weak labels, unlabeled data, and semi-supervised learning, to enhance the effectiveness of defect detection. This approach not only helps reduce the reliance on large amounts of annotated data, thereby lowering costs, but also enhances detection performance.

Data availability

The data used in this study involves confidential company information. If needed, please contact the corresponding author to request access to certain data.

References

Ding, L. et al. Quality inspection of micro solder joints in laser spot welding by laser ultrasonic method. Ultrasonics 118, 106567 (2022).

Xiao, G., Hou, S. & Zhou, H. PCB defect detection algorithm based on CDI-YOLO. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 7351 (2024).

Wu, S., Yang, J., Wang, X. & Li, X. Iou-balanced loss functions for single-stage object detection. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 156, 96–103 (2022).

Zhang, H., Zhang, S. & Shape-iou More accurate metric considering bounding box shape and scale. https://arxiv.org/abs/2312.17663 (2023).

Zhang, H., Xu, C. & Zhang, S. Inner-IoU: More effective intersection over union loss with auxiliary bounding box. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.02877 (2023).

Chen, Y. et al. Yolo-ms: Rethinking multi-scale representation learning for real-time object detection. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.13616 (2023).

Fan, F. L., Wang, B. Y., Zhu, G. L. & Wu, J. H. Efficient faster R-CNN: Used in PCB solder joint defects and components detection. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on Computer and Communication Engineering Technology 1–5 (IEEE, 2021).

Kim, C., Hwang, S. & Sohn, H. Weld crack detection and quantification using laser thermography, mask R-CNN, and CycleGAN. Autom. Constr. 143, 104568 (2022).

Ji, C., Wang, H. & Li, H. Defects detection in Weld joints based on visual attention and deep learning. Ndt E Int. 133, 102764 (2023).

Cherkasov, N., Ivanov, M. & Ulanov, A. Weld surface defect detection based on a laser scanning system and YOLOv5. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing 851–855 (IEEE, 2023).

Liu, M. Y., Chen, Y. P., Xie, J. M., He, L. & Zhang, Y. LF-YOLO: A lighter and faster YOLO for Weld defect detection of X-ray image. IEEE Sens. J. 23(7), 7430–7439 (2023).

Wang, G. Q. et al. Yolo-MSAPF: Multiscale alignment fusion with parallel feature filtering model for high accuracy Weld defect detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–14 (2023).

Kwon, J. E., Park, J. H., Kim, J. H., Lee, Y. H. & Cho, S. I. Context and scale-aware YOLO for welding defect detection. NDT E Int. 139, 102919 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Seesaw loss for long-tailed instance segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 9695–9704 (2021).

Tan, J., Lu, X., Zhang, G., Yin, C. & Li, Q. Equalization loss v2: A new gradient balance approach for long-tailed object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 1685–1694 (2021).

Wang, T. et al. Adaptive class suppression loss for long-tail object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 3103–3112 (2021).

Yue, X., Mou, N., Wang, Q. & Zhao, L. Revisiting Adversarial Training under Long-Tailed Distributions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 24492–24501 (2024).

Zhang, Y. & Deng, W. Class-balanced training for deep face recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 824–825 (2020).

Lazarow, J. et al. Unifying distribution alignment as a loss for imbalanced semi-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision 5644–5653. (2023).

Xu, Z., Liu, R., Yang, S., Chai, Z. & Yuan, C. Learning imbalanced data with vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 15793–15803 (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. Yolo-facev2: A scale and occlusion aware face detector. Pattern Recogn. 155, 110714 (2024).

Wang, T. et al. C2am loss: Chasing a better decision boundary for long-tail object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 6980–6989 (2022).

Rezatofighi, H. et al. Generalized intersection over union: A metric and a loss for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 658–666 (2019).

Zheng, Z. et al. Distance-IoU loss: Faster and better learning for bounding box regression. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 12993–13000 (2020).

Zheng, Z. et al. Enhancing geometric factors in model learning and inference for object detection and instance segmentation. IEEE Trans. Cybernetics. 52(8), 8574–8586 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Focal and efficient IOU loss for accurate bounding box regression. Neurocomputing 506, 146–157 (2022).

Gevorgyan, Z. SIoU loss: more powerful learning for bounding box regression. https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.2740 (2022).

Siliang, M. & Yong, X. MPDIoU: A loss for efficient and accurate bounding box regression. https://arxiv.org/abs/2307.07662 (2023).

Zhang, H., Zhang, S. & Focaler-IoU More focused intersection over union loss. https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.10525 (2024).

Lin, T. Y. et al. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2117–2125 (2017).

Liu, S., Qi, L., Qin, H., Shi, J. & Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 8759–8768 (2018).

Wang, C. Y. et al. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops 390–391 (2020).

Wang, C. Y., Bochkovskiy, A. & Liao, H. Y. M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 7464–7475 (2023).

Lyu, C. et al. Rtmdet: An empirical study of designing real-time object detectors. https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.07784 (2022).

Wang, C. Y., Liao, H. Y. M. & Yeh, I. H. Designing network design strategies through gradient path analysis. https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.04800 (2022).

Wang, C. Y., Yeh, I. H. & Liao, H. Y. M. Yolov9: learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.13616 (2024).

Kirillov, A. et al. Segment anything. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 4015–4026 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.J.X. conceived the experiment. W.J.H. conducted the experiment. Z.X.Y. reviewed the data. L.Z.G. directed the data analysis. D.Y.M. statistics. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Feng, J., Wang, J., Zhao, X. et al. Laser weld spot detection based on YOLO-weld. Sci Rep 14, 29403 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80957-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80957-3

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Heterogeneous attention multi-scale network for efficient weld seam classification

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A real-time closed-loop control system for adaptive robotic welding: a step toward intelligent welding

The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology (2025)