Abstract

Clustering plays a crucial role in data mining and pattern recognition, but the interpretation of clustering results is often challenging. Existing interpretation methods usually lack an intuitive and accurate description of irregular shapes and high dimensional datas. This paper proposes a novel clustering explanation method based on a Multi-HyperRectangle(MHR), for extracting post hoc explanations of clustering results. MHR first generates initial hyperrectangles to cover each cluster, and then these hyper-rectangles are gradually merged until the optimal shape is obtained to fit the cluster. The advantage of this method is that it recognizes the shape of irregular clusters and finds the optimal number of hyper-rectangles based on the hierarchical tree structure, which discovers structural relationships between rectangles. Furthermore, we propose a refinement method to improve the tightness of the hyperrectangles, resulting in more precise and comprehensible explanations. Experimental results demonstrate that MHR significantly outperforms existing methods in both the tightness and accuracy of cluster interpretation, highlighting its effectiveness and innovation in addressing the challenges of clustering interpretation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The advancement of technology brings artificial intelligence (AI) closer to people, playing significant support roles across various domains. Machine learning algorithms are prevalent in healthcare, credit lending, and fraud detection. However, these algorithms are often black boxes1 producing excellent results but with opaque decision-making processes that are difficult to understand. Transparency and interpretability are crucial in many applications, especially as researchers introduce AI into high-sensitivity and high-risk environments. Users increasingly must understand the information conveyed by AI decision-making processes. The interpretability and comprehensibility of outcomes are closely linked to the explanations of their resukts provided by models. Despite the growing usefulness of AI systems and their numerous benefits, the lack of explanations for decisions and actions hinders their adoption, causing users to view them as untrustworthy. The challenge is to enhance the interpretability of AI, build user trust, and facilitate user comprehension and management of AI outcomes. Not all AI models are immune to this interpretation. Some simpler models are inherently interpretable, albeit less accurate, but more favorable to users. Many approaches such as attribute grouping, for example, are designed to meet machine learning’s need for transparency and interpretability, helping users understand which features influence decisions. Therefore, trust and understanding are the keys to increasing users’ adoption of AI models2.

Clustering is a data mining method that combines similar data points. Cluster analysis divides a set of objects into several homogeneous subgroups based on a similarity measure, ensuring that the similarity among objects within the same subgroup exceeds that among objects belonging to different subgroups. In clustering, attribute grouping usually refers to the grouping of features in a dataset based on similarity or correlation for better understanding and processing of data3. Traditional clustering analysis methods fall into several categories such as partitioning, hierarchical, density-based, grid-based, and model-based methods. Clustering algorithms have various practical applications. In business, clustering assists market analysts in identifying various customer segments from customer groups and describing the characteristics of different customer segments using purchasing patterns4. Biology uses clustering to infer the classification of plants and animals, classify genes, and gain an understanding of inherent structures within populations5,6,7,8. Clustering also classifies documents on the web to search for information9.

Interpretative clustering is the ability to interpret the obtained clustering results after performing a cluster analysis10. Clustering is an unsupervised learning task, its goal is to classify objects into clusters based on similarity without category labeling. However, the goal of interpretative clustering is to provide a way for even non-expert users to understand how clusters are formed and why certain data points are grouped into the same category11. This can be accomplished by using simple geometric shapes, such as hyper-rectangles, that map directly into the original feature space and are easy to understand and interpret.

The demand for interpretability in machine learning arises not only from practical needs but also from legal regulations12. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)13, which became effective in May 2018 in the European Union, states that decisions made by machines about individuals must adhere to interpretability requirements.

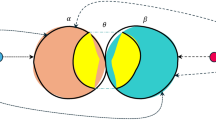

This paper focuses on cluster explanation description. Given a fixed cluster partition of a set of data points with real or integer coordinates, there are several methods to generate humanly describable rules14. Existing work on clustering description concerns employing interpretable supervised learning methods to predict cluster labels. Common categorizations showcase decision patterns of clustering algorithms through forms such as decision trees, rules, and rectangular boxes, among others. One of the methods for explainable clustering is identifying axis-aligned hyperrectangles15 in the data because simple rules can easily describe hyperrectangle boundaries. The illustration of interpretive classification appears in Fig. 1, The detailed description is as follows.

Rule-based interpretation of clustering

Most samples in clusters can be represented by one or more rules, which reflects the interpretability of the algorithm. Depending on the partitioning methods of rule premises, rule-based algorithms can be divided into adaptive partitioning or fixed grid partitioning. S. Sandhya16 proposed an adaptive partitioning method, which enhances the interpretability of the clustering results of the k-means algorithm and adjusts samples in clusters that do not meet interpretability requirements. The interpretability of each cluster appears in the proportion of the same feature values with the highest frequency among samples within the cluster. Wang et al.17 proposed a rule-based soft clustering method. The distinctive feature of this paper is the integration of information provided by the dataset into the traditional triangular membership function and the alteration of the fuzzy division. After normalization, based on the specified number of clusters K, the method selects K-1 points as intersection points for two membership functions at equal distances (at this point, the membership of two membership functions is 0.5).Then the average value of samples within each interval is taken as the vertex of the membership function in that interval (i.e., the membership is 1). This approach enables fuzzy partitioning of each attribute. However, it fails to ensure that the sum of sample membership degrees for all fuzzy sets equals 1, which may affect its interpretability. For fixed grid partitioning rule interpretation, E G. Mansoori18 used triangular membership functions as the partitioning method. Injecting randomly generated auxiliary data into the original dataset to form a two-class problem transforms the clustering problem into a classification problem. Using a classification algorithm to create rules is an innovative rule-generation approach. Moreover, users do not need to provide additional information, making the algorithm highly applicable. Rule-based clustering explanation19,20,21 sometimes generates unnecessary rules, which diminishes the explanation of the algorithm.

Rectangular boxes interpretation of clustering

Rectangular bounding boxes generate clustering explanations by feature dimensions. D. Pelleg22 proposed a soft clustering method using hyperrectangles as boundaries for the cluster. Since these hyperrectangles may overlap, he introduced a Gaussian function to generate a soft “tail” to compute the affiliation of the samples to the different rectangles. The model proposed by J. Chen23 is the Discriminative Rectangular Mixture (DReaM) model. DReaM uses only the rule-generating functions to construct clustering rules, and the cluster-preserving functions to find the clustering structure. In addition, the model can integrate prior knowledge to determine the distribution of boundaries of hyperrectangles. For rectangle-based clustering explanation, there is a lack of valid solutions for irregularly shaped clusters.

Decision tree interpretation of clustering

Top-down binary trees are popular methods for clustering and classification24,25. They classify the dataset through feature selection and cut-point selection at each node. Their interpretability can be reflected by the selection of split points. G. Badih26 made modifications to traditional information gain. Uniformly adding auxiliary samples to the sample space generates class labels for calculating information gain. This paper fully exploits the role of low-density regions, selecting split points that produce low-density regions as final split points, allowing samples near the original split point that may be misclassified to enter the correct area, thereby optimizing the traditional decision tree algorithm. Dasgupta et al.27 proposed utilizing labels provided by the k-means algorithm. The algorithm is a top-down binary decision tree that traverses all partition nodes, finding the partition method with the lowest relative class label error rate compared to k-means and dividing it until the class labels of samples in the child nodes are consistent and marking them as leaf nodes. This algorithm increases the interpretability of clustering results without changing traditional clustering results. For decision tree-based clustering explanation, it is easy to create problems with more branches and too deep leaves28,29.

Among these three methods of interpretation, researchers have studied the rules and decision trees thoroughly. The studies concerning the interpretation of clustering based on rectangular boxes show that uniformly distributed datasets are most used for traditional rectangular box description clustering, making it challenging to achieve good interpretive results for irregular and high-dimensional datasets. Therefore, this paper intends to conduct further research based on the interpretation form of multi-hyperrectangle.

This paper introduces a new cluster description method that identifies the geometric convex hull points of the dataset and creates multiple polyhedral hyperrectangles around each cluster. Hence, it is named Multi-Hyperrectangle Description. Initially, each hyper-rectangle forms using two adjacent convex hull points. Considering that the excessive number of hyperrectangles generated by the initial convex points complicates the interpretation, we introduce a rectangle merging algorithm to improve the quality of the interpretation. Whether the interpretability of these hyperrectangles meets the balance between complexity and efficiency depends on the cluster’s average hyperrectangle density. It is the ratio of the number of data points in the dataset covered by the hyperrectangles to the average area or volume of the hyperrectangles.

We are studying the description of the interpretation after clustering. In this scenario, we establish a link between features and cluster labels through hyperrectangles. The explanation provided by hyperrectangles can be interpreted as several rules connected by AND and OR operators, which fit the data distribution in terms of optimal quantity and scope, ultimately deriving easily understandable explanations.

Main contributions

We summarize our main contributions as follows:

-

We introduce the method of multi-hyperrectangle explained clustering, aimed at explaining clusters by constructing axis-aligned hyperrectangles around them.

-

We formulate the hyperrectangles generation problem as a convex hull algorithm search problem. Convex hull points that form the vertices of hyperrectangles can tightly cover datasets with irregular distribution.

-

We conduct numerical experiments on several real-world clustering datasets, demonstrating that our method performs well compared to other rectangular box interpretation clustering methods.

The remainder of this paper is as follows: “Proposed method” section provides a formal description of the hyperrectangle generation problem and proposes a dendrogram-based method merging hyperrectangles and a refinement process to construct clustered optimal explanatory descriptions. “Experimental results and comparisons” section presents numerical results on commonly used UCI clustering datasets. Finally, “Discussion” section concludes the paper.

Proposed method

Overview

In this section, we present the details of the proposed multi-hyperrectangle based interpretation algorithm(MHR), of which the primary intuition is from multi-prototype based clustering. In multi-prototype clustering, each cluster can consist of multiple prototypes (e.g., means, centroids, etc.) rather than just a single prototype. When faced with the complexity of a class structure, multiple prototypes are more closely covered than a single prototype.

Before the details, we formulate the explanation problem as follows. Suppose the input data consists of n data points, denoted as \(X=\left\{ x_{1},x_{2},...,x_{i},...,x_{n} \right\}\), of which each data point has m features, i.e., \(x_{i}=\left( x_{i1},x_{i2},...,x_{ij},...,x_{im} \right) ^{T} \in \mathbb {R} ^{m}\). For a given clustering algorithm, X is partitioned into k clusters, which are denoted by \(C_{1},C_{2},...,C_{k}\). To interpret a cluster \(C_i\), one must find an optimal set of hyperrectangles, \({R_1,...,R_K}\), to cover \(C_i\) tightly.

When we would explain clustering, we find that one hyperrectangle cannot handle complex cluster structures. Next, we choose the multi-hyperrectangle clustering interpretation algorithm, which assigns data points to their nearest hyperrectangles. Each hyperrectangle represents an interpretation. Multiple hyperrectangles can cover a cluster. It can capture the complex structure and distribution of the data more flexibly, paying attention to running the algorithm on a well-clustered dataset. In our approach, the interpretation process comprises the following three steps, which appear in Fig. 2.

Step 1. Initialize the hyperrectangle cover

-

Cluster the dataset X into \(C_1,...,C_k\).

-

Collect the convex points \(U_i\) corresponding to \(C_i\) for each cluster.

-

Construct the initial hyperrectangles based on features of data points in \(U_i\) and assign the data points to the corresponding hyperrectangles.

Step 2. Merge the hyperrectangles

-

Calculate the similarity between hyperrectangles: For each pair of neighboring hyperrectangles, design a new similarity metric to iteratively merge the most similar hyperrectangle pairs. Eventually, it presents a dendrogram of merging hyperrectangles.

-

Observe the optimal number of rectangles by a similarity line chart.

-

Merge the hyperrectangle according to the stopping criterion above and plot the result on the clusters.

Step 3. Refine hyperrectangles and obtain the final interpretation result

-

Find the redundant area of the hyperrectangle by density difference.

-

Prune the redundant area of hyperrectangles for better interpretation.

The example dataset for the algorithm is a 2D moonshape dataset. (a) A clustered moon dataset. (b) Find the convex points by Quick hull convex algorithm. (c) The initial hyperrectangles are generated by connecting neighboring convex hull points according to the principal dimension. (d) Generate a dendrogram by treating hyperrectangles as leaf nodes. (e) Find the stop criterion. (f) Merge neighboring hyperrectangles to generate an optimal number of hyperrectangles. (g) Find the cut line. (h) Cut redundant areas. (i) Results of interpretable hyperrectangles.

Initialization of hyperrectangles

In the past there were several ways to find the rectangle that covers the data. One traditional method is the Minimum Bounding Rectangle (MBR) algorithm30. When the boundaries of an object are known, it is easy to use the dimensions of its outer rectangle to characterize its basic shape. When the condition of parallelism of the axes of the rectangular frame is not considered, more efficient algorithms like the Rotating Calipers Algorithm31 may be necessary. It first finds the convex hull points of the data and then selects the individual edges of the convex hull to construct all possible boundaries. However, when applying them to clustering explanations, the quality of the explanation needs to be considered. A rectangle covering the complex dataset will inevitably produce many redundant areas, which is a challenge for interpretation. Therefore, this paper proposes an algorithm that divides the clusters into various rectangles in conjunction with the geometric convex hull algorithm, which covers all the points while fitting the arbitrary shape of the clusters with hyperrectangles. It ensures that neighboring points are in the same rectangle (as much as possible) and different groups of hyperrectangles surround those points in other clusters.

Considering the diverse shapes of clusters, attempting to decompose shapes based on their structure is a highly complex and time-consuming task. Therefore, our method does not make any assumptions about the shape of regions that it must refine. For example, oblique impacts, reflected impacts, etc., can form regions with diagonal lines or “S” or “U” shapes. Our algorithm is entirely general-purpose.

Many computational geometry methods rely on the convex hull (CH)32. The convex hull algorithm solves the problem of finding a polygon that covers a given set of points, with its vertices composed of these points. When applying the clustering interpretation, a convex hull point is the class of points furthest from the cluster center, which is more conducive to interpretation using the dimensional coordinates of these points. Popular convex hull algorithms include Quick Hull, Graham’s Scan, and Gift Wrapping. These algorithms efficiently discover contour points based on the shape of clusters. We apply the Quick Hull algorithm to our method implementation and adopt a divide-and-conquer approach by recursively dividing the point set into smaller subsets to construct the convex hull. We can use it in both low and high dimensions. The time complexity of the Quick Hull algorithm depends on the shape of the convex hull, with the worst-case time complexity of \(O\left( n^{2} \right)\) and the average-case time complexity of O(nlogn)33, where n is the number of points. The set of extreme points (vertices) of a convex hull is defined as follows:

Definition 1

The convex hull of X is the smallest convex set containing X, defined as:

where \({\textbf {x}}_{i}\) is a vector, \(\lambda _{i}\) are non-negative scalar coefficients.

P is a subset of X. In particular, the set of vertices in P constructs a frame of X, which is the intersection of all the half-planes containing X. The shape of P is a polygon.

Definition 2

A point o of P is an extreme point if there are no other two points p and q in P such that o lies on the line segment \(\overline{pq}\). o is defined as

When we obtain all the extreme points, they form the convex hull of X. We find that the vertices of P describing the convex hull are precisely the extreme points of the convex hull set enclosing the points of X.

Next we describe the detailed procedure of the algorithm to find the convex hull points of X, which appears in Fig. 3. In our implementation of Quick Hull we followed the guidelines given by Eddy34 (the space-efficient alternative):

-

Find the two poles of datasets by one scan, the west pole p and the east pole q, which appears in Fig. 3a.

-

Partition the remaining points between p and q into upper-hull and lower-hull candidates: Q1 contains those points that lie above or on the line segment \(\overline{pq}\) and Q2 contains those that lie below it, as shown in Fig. 3b.

-

Find the extreme point o in Q1 which is furthest from \(\overline{pq}\) and connect the o, p, q to form a triangular region in Fig. 3c.

-

Eliminate the points inside the triangular region. Partition the points line above the \(\overline{op}\) as new upper-hull candidates and find the new extreme point \(o'\), as illustrated in Fig. 3d.

-

Fig. 3e is the recursive operation on the other upper-hull region to eliminate all interior points and find all extreme points.

-

Equally, apply the recursive operation for the lower-hull candidates Q2 in Fig. 3f. Now, you have found all the extreme points, which are the convex hull points of X.

Algorithm 1 outlines theis subroutine.

After applying the Quick Hull algorithm to each cluster, it identifies the convex hull points.

Definition 3

Let \(U_i\) be the set of convex hull points of cluster \(C_i\):

where \(U_i\subseteq C_i\), \(\left| U_i \right| =u\).

Then, another consideration arises of how to use these convex hull points to generate hyperrectangles. Simply connecting any adjacent two points to form hyperrectangles may result in a complex set of rectangles, of which the dimensional intervals of these rectangles overlap and increase the complexity of interpretation. So, we choose to collect the coordinates of these points and calculate the difference between the maximum and minimum values for each feature to ensure human-understandable explanations. Then, we identify the dimension corresponding to the feature with the largest difference (i.e., the dimension with the greatest variation), defining this dimension as the cluster’s primary dimension. The formula is as follows, which appears in Fig. 4.

Hyperrectangles in the primary dimension must not overlap to avoid complicating the interpretation. Once the primary dimension is determined, we can construct initial hyperrectangles after sorting the convex hull points based on the feature values of the primary dimension.

Definition 4

Let \(Rank\left( U_i \right)\) be an ordered list sorted on the \(d_m\) dimension as in

Definition 5

Let \(R_i\) be the rectangle generated by joining two neighboring points of \(Rank\left( U_i \right)\) as in

At this point, the initial hyperrectangle construction is complete. We construct each hyperrectangle between two adjacent convex hull points and the number of hyperrectangles is \(u-1\). Figure 5 illustrates the convex hull algorithm on a moon-shaped dataset.

Dendrogram-based merging of hyperrectangles

Due to the nature of the Quick Hull algorithm, which does not allow users to specify the number of convex hull points generated, the initial number of hyperrectangles may be enormous. Each hyperrectangle may cover too few points, resulting in an increased complexity of interpretation due to the proliferation of “AND” conditions. The next step is to perform hyperrectangle merging operations.

Merge process

We get the idea from the agglomerative hierarchical algorithm. We treat each hyperrectangle in the cluster as a separate leaf node of a binary tree, defined as the set \(T=\left\{ R_1,R_2,...R_{u-1} \right\}\).

Essentially, this process constructs a hierarchical structure of binary trees, starting from the data elements stored in the leaves (interpreted as singleton sets) and continuing to merge pairwise the closest subsets (stored in nodes) until it reaches the root of the tree containing all elements of X. Using the primary dimension as the base axis, we sequentially calculate the similarity between adjacent hyperrectangles. Since these hyperrectangles are adjacent, we design a new similarity rule.

Definition 6

Let define the similarity between hyperrectangles as follows:

where \(\left| R_i \right|\) represent the number of points in the \(i-th\) hyperrectangle, \(L_id\) represent the edge length of the \(i-th\) hyperrectangle in dimension d.

The density value is the ratio of the number of points in the hyperrectangle to the area (volume) of the hyperrectangle, referring to equation (7). Considering that the density value decreases after the hyperrectangles are merged while the tree graph generally has the coordinates of the parent node higher than the child nodes, we make the inverse of the density in equation (8) as the definition of the hyperrectangles distance. The smaller the reciprocal density value, the closer the hyperrectangles, and the higher the priority for merging.

Then, based on the similarity of these hyperrectangles, we merge the most similar pair of hyperrectangles and form a new layer \(T_i\) of the binary tree with the remaining hyperrectangles, of which the merging process appears in equation (9). We construct a complete binary tree by repeating the merging process until only one hyperrectangle remains, which is the root of the binary tree.

where \(T_{merge}(R_i\circ R_j)\) is which obtained by merging \(R_i\) and \(R_j\), \(\circ\) is concatenate operator, used to merge two adjacent hyperrectangles.

In Fig. 6, we assume that each data point occupies 1 unit of space. The three rectangles in Fig. 6a are saturated with data points, so the area is the number of points. The area of the redundant region is the number of evenly placed full data points.

The similarity values of the two merging approaches are calculated separately by the distance formula proposed above. Where the new rectangle distance value for (b) is 4/3 (48/36) and for (c) is 8/7 (48/42). Therefore, we choose (c) with the smallest similarity value as the final merged result.

In the merging process, we identify the rectangles with the smallest distance and merge them iteratively until only one rectangle (the root node) remains. We draw a complete dendrogram based on the merging operations and the corresponding distance values. Conceptually, Fig. 7 illustrates a dendrogram of the 2D moon-shaped dataset.

Stop criterion

We propose a stopping criterion to determine the optimal number of hyperrectangles in the dendrogram of merging rectangles: The farther the vertical lines are, the greater the distance between rectangles. We find the layer of child nodes with the largest distance between nodes in the dendrogram. Its height indicates the optimal number of rectangles covering the cluster. Of course we can represent it visually. We set the similarity of the hyperrectangles as the horizontal coordinate and the number of hyperrectangles as the vertical coordinate. Plot the similarity between the two hyperrectangles merged in each round and the corresponding number of hyperrectangles as coordinate points and connect them to form a line graph, representing the trend change in the distance of the merged hyperrectangles. Figure 8 illustrates the specific workflow.

Definition 7

Let K be the number of rectangles with the maximum difference between \(S(T_i)\) and \(S(T_{i+1})\):

where \(S\left( T_{i} \right)\) is the similarity value corresponding to the \(i-th\) level of the tree.

When a span of the horizontal axis between two nodes is too large, it indicates that the hyperrectangles are no longer suitable for merging at this point. We use the vertical coordinate corresponding to the node before merging as the final number of hyperrectangles. To reduce the complexity of interpretation, we assume that the number of rectangles covering an arbitrarily shaped cluster is no more than 5. If K exceeds the typical optimal solution, failing to mention the structure of the cluster, we set K=1. When K rectangles meet the density criteria, we can generate the final interpretation result.

A line graph showing the distance values of the nodes on the dendrogram:We choose the width to cut the dendrogram. For a given width, we get a corresponding count of rectangles (i.e., the entire cluster is partitioned by the selected number of rectangular boxes). Here, we show the optimal cutting path, for Rectangles Count = 3.

The pruning of hyperrectangles

During the process of merging hyperrectangles, some issues may arise, which may produce a redundant area leading to a degradation in the quality of the interpretation. Figure 9 depicts two problems. One potential issue is the excessive presence of empty areas within the hyperrectangles shown in Fig. 9a. When a long hyperrectangle encounters a short one, the difference in height between them influences the poor interpretative effectiveness of the new hyperrectangle. Moreover, noise points within the hyperrectangles pose another challenge, as shown in Fig. 9b. Within a cluster, several points are often distant from the other points. While this may not pose a significant problem when observed locally, the harm caused by noise points becomes evident when multiple hyperrectangles merge into a whole. In such cases, a few data points may occupy a large portion of the hyperrectangle, while other densely clustered data points occupy another part. This situation is unfair to compact datasets and requires excessive space to interpret the area where the noise points exist.

We reduce unintended rectangular areas by designing a post-processing mechanism to further prune the hyperrectangles after the merging process based on the hierarchical tree structure. Before performing the pruning operation, we must ensure that we do not apply it along the primary dimension. Thus, the interpretation after pruning is continuous in the main feature interval. If not done so, it may cut through adjacent regions of the hyperrectangles, leading to discontinuous interpretation intervals, which is not in line with the interpretation requirements. Figure 10 illustrates this situation.

In Fig. 10, where (b) is the solution proposed by our algorithm, (c) seems to work as well as b but leads to discontinuous interpretation intervals. Next, (d) seems to work better but also leads to discontinuous interpretation intervals as well as in high dimensional space. If it cuts the hyperrectangles from multiple dimensions simultaneously, it may lead to many non-noise points being cut outside the box. It draws conclusions that ensure feature intervals on the primary dimension for interpretation are continuous. Before pruning the hyperrectangles, we first need to mark and exclude the primary dimension of the hyperrectangle, defined as \(d_m\). Then, we perform the following operations on the other dimensions:

-

Sort the dataset within the hyperrectangle according to the currently selected dimension d.

$$\begin{aligned} Rank\left( X\in Ri \right) =\left\langle x_{1}^{'},x_{2}^{'},...,x_{n}^{'} \right\rangle _{d} \end{aligned}$$(11)where n represents the number of data points.

-

Assume a cutting line is generated on the feature values along the dth dimension, dividing the hyperrectangle into two intervals, \(r_{1i}\) and \(r_{in}\), as in Fig. 11.

-

Calculate the data density values for the two intervals, as per Formula (8).

-

Calculate the numerical difference between the two intervals and store it in absolute value.

$$\begin{aligned} \triangle \rho _{i} =\left| \rho \left( r _{1i} \right) -\rho \left( r _{in} \right) \right| \end{aligned}$$(12) -

After calculating the results for all points and dimensions, identify the point with the maximum absolute value of the density value difference, representing the optimal dimension and cutting point.

$$\begin{aligned} l,x_{i}^{'} \leftarrow argmax \sum _{l=1,l\ne d_{m}}^{m} \sum _{i=1}^{n} \triangle \rho _{il} \end{aligned}$$(13)

Formula (13) embodies the algorithm’s logic to find the optimal dimension l and cutting point \(x_{i}^{'}\). It enables us to split the hyperrectangle into a dense and a sparse interval. The sparse interval may contain very few discarded points, minimizing losses to the overall cluster interpretation.

Sometimes, it is better to prune multiple dimensions simultaneously, depending on the situation. In lower-dimensional spaces, we can apply the optimal cutting line for each dimension to the current hyperrectangle. However, we found excessive dimension cutting in high-dimensional data removes almost all data, leaving behind a very small hypercube. Therefore, after completing these procedures for each dimension except the primary dimension, we must select the dimension with the fewest cut data points. Then, we prune the hypercube according to its cutting line. This method ensures the efficiency of interpretation while preserving most of the dataset.

At this point, this paper has described each step of the algorithm in detail. Pseudocode and related details of the MHR appear in Algorithm 2.

Experimental results and comparisons

This section presents the experimental results of our proposed hyperrectangles clustering interpretation method. To evaluate the performance of the algorithm, we conducted a series of experiments on both synthetic and real-world datasets to demonstrate its effectiveness in providing interpretable clustering results. We compared the results with existing rectangular box clustering interpretation algorithms to highlight improvements in interpretability and robustness. During the experiments, we ensure that each set of experiments is run under the same conditions, including the same hardware environment and software configuration. In addition, we performed multiple experimental runs on each dataset to assess the consistency and stability of the algorithm.

Experimental Setup: We implemented our method using the Python programming language and leveraged popular libraries such as NumPy, SciPy, and scikit-learn. We implemented the convex hull algorithm for generating hyperrectangles in the algorithm using the SciPy. spatial library. The experiments ran on a computer with 8 GB RAM and a 2.3 GHz processor.

Synthetic dataset

We generated synthetic datasets with varying complexities to thoroughly evaluate the algorithm’s robustness, scalability, and capability to handle different shapes of cluster structures:

We selected four 2-dimensional datasets and generated corresponding plots of the hyperrectangle results to visualize the interpretation results better. To illustrate the entire process of the proposed algorithm, we first considered the moon-shaped dataset shown in Fig. 2. This dataset consists of two curved clusters resembling crescent moons. We generated the dataset using the make_moons function with 200 samples and a noise parameter of 0.08. We employed the DBSCAN algorithm to model the clustering effectively, setting the parameters eps to 0.2 and min_samples to 5. For the convex hull algorithm, we choose Quick Hull because it provides faster and more stable characterization of convex hull points in various dimensional datasets.

Taking the moon-shaped cluster as an example, In the first stage of the algorithm, by means of the convex hull algorithm, we identified twelve convex hull points. After calculating the main dimension as the x-axis, eleven neighboring rectangles were generated by connecting the convex hull points along the main dimension. In the second stage, we calculated the similarity between neighboring rectangles and plotted the dendrogram shown in Fig. 7. In the line graph of the stopping criterion in Fig. 8, we can find that the vertical distance between the leaf nodes of the second and third layers is the maximum. Therefore, we selected the nodes from the third layer as the final rectangles, resulting in three rectangles. At this point, we find that three rectangles covering the cluster is the perfect result, not only fitting the shape of the dataset but also reducing consumption of rectangles. In the final stage, in response to the extra space complexity caused by the discrete points in the rectangles, we pruned the three rectangles in the clusters and further refined the interpretation rules, thus improving the cluster interpretation score. Due to the similarity in shape between the two clusters in the dataset, the steps of the algorithm for the other cluster are the same, and finally the three rectangles ultimately covered each cluster to complete the interpretation.

In addition, we applied our proposed algorithm to three other 2-dimensional datasets commonly used to test clustering algorithms: Flame, Smileface, and T4.8k. Figure 12 illustrates the clustering and interpretation results for these datasets. Flame consists of two connected clusters, one with a uniformly distributed elliptical structure and the other with a crescent moon shape, which was selected to test the algorithm’s ability to differentiate between clusters of varying densities and shapes. Smileface resembles a smiley face image and comprises four clusters. T4.8k is a dataset containing 8000 data points, composed of seven density clusters of various shapes nested within each other and contaminated with many noise points. The algorithm provided optimal sets of rectangle interpretations for these datasets with varying shapes and sizes. The interpretation results for the highly complex dataset T4.8k demonstrate that the algorithm effectively handles complex clusters. The algorithm displayed its robustness by successfully identifying these irregular data structures.

The clustering results obtained by the proposed algorithm on these 2-dimensional datasets are illustrated. For Flame, Smileface, and T4.8k, the total number of rectangles obtained for modeling the clusters is 4, 6, and 14, respectively. From these numbers, we can observe that the proposed algorithm successfully identified the clustering structures present in these datasets.

Real dataset

We further evaluate our approach by running experiments on five different clustered datasets from the UCI Machine Learning Repository35. The Iris dataset is a widely used benchmark dataset containing samples of Iris with four features. The Liver Disorders dataset has seven attributes, and we use its first five variables on blood tests. Ecoli contains protein localization sites and seven attributes. Seeds measures the geometric properties of wheat grains belonging to three different wheat varieties. Wholesale refers to clients of a wholesale distributor, which includes the annual spending in monetary units (m.u.) on diverse product categories. Glass Identification from the USA Forensic Science Service has six types of glass. The wine dataset divides 13 attributes and 178 data into three categories. These datasets have different feature dimensions and distributional properties, enabling a comprehensive assessment of the performance of our method relative to other rectangular box interpretation clustering methods. These five datasets appear in Table 1.

To ensure that the convex hull algorithm runs successfully on high-dimensional datasets, we use a correlation filter on the dataset to ensure that the number of clusters in each cluster meets the requirements of the convex hull algorithm. For high dimensionality, when the amount of data in a single cluster is less than the number of dimensions or located in a plane where the convex hull algorithm cannot be applied, we choose to generate a single hyperrectangle based on the coordinates of these points, directly used as the interpretable result of the rectangular box.

The example of explanations

The hyperrectangles obtained by MHR find regular decision boundaries for each cluster and generate the explanation for each cluster. The paper selects an example from the synthetic and the real dataset to show the explanation results. Table 2 shows the explanation of each cluster in the moon-shaped dataset. The explanations corresponding to the rectangles in each cluster are joined in the table using the ’\(\cup\)’ operator. Table 3 shows the explanation of each cluster in the Iris dataset. The corresponding categories of Iris can be distinguished by the distribution of sepal length and width and the distribution of petal length and width.

Assessment of indicators

We use a variety of evaluation metrics to assess the performance of our method and compare it to other interpretive methods. These metrics include:

Accuracy

It assesses the extent to which the clustering algorithm correctly classifies the samples. It evaluates the performance of supervised clustering, which compares the clustering results with the true labels. It is calculated by matching each clustered cluster with its corresponding true label and then calculating the ratio of correctly classified samples to the total number of samples36. The formula is:

NMI (Normalized Mutual Information)

NMI is an evaluation index comparing the clustering results with the real labels37, considering the consistency and completeness between the clustering results and the real labels. The specific calculation measures the correlation between the two by calculating and standardizing their mutual information. The value of NMI ranges from 0 to 1, and the higher the value, the more consistent the clustering results are with the real labels38. The formula for calculating NMI is more complicated and usually uses matrix operation.

FM (Fowlkes-Mallows Index)

FM is a metric used to evaluate the accuracy of a clustering algorithm39. It combines the true positives, false positives and false negatives in the clustering results. The FM index is the ratio of the number of true positives to all pairs of samples in the clustering results, where true positives indicate that samples belonging to the same category in the true labels also belong to the same clusters in the clustering results. The specific calculation formula is:

where TP denotes true positives (number of sample pairs with the same category in both the clustering result and the true label), FP denotes false positives (number of sample pairs misclassified in the clustering result), and FN denotes false negatives (number of sample pairs with the same category in the true label but misclassified in the clustering result).

Accuracy, NMI, and FM are metrics used to evaluate the performance of clustering algorithms, where the method uses Accuracy when samples have real labels. It evaluates the performance of the algorithm by comparing the clustering results with the real labels. NMI and FM are more applicable when the samples do not have real labels available. They evaluate the performance of the algorithm based on the similarity between the clustering results.

Interpretability score

Considering that the rectangular box interpretation method currently has no article proposing a corresponding interpretation score formula, this paper proposes a specific hyperrectangle interpretation score guideline. When using the hyperrectangles to explain clustering, two situations affect the results. The first is the box density. The denser the data, the fewer redundant areas when the explanation is better. The second is the hyperrectangle overlap rate when the hyperrectangle crosses and overlaps to cover a data point simultaneously. The interpretation of this data point is fuzzy and unclear. We can interpret a dataset correctly only when a hyperrectangle frames it.

Considering these two cases together, we utilize the density formula mentioned above to calculate the average density value of the entire dataset in a single hyperrectangle. Together with the hyperrectangle overlap rate, we construct the interpretable score algorithm. Our method can qualitatively assess the interpretability of the generated hyperrectangle clusters more efficiently than other interpretation methods. The value of IS is between 0 and 1. The smaller the value, the denser the data and the less overlapping rectangular area, so the clustering interpretation is the best. The following is the interpretability score formula:

where \(z\left( x_i \right)\) denotes the number of hyperrectangles that contain \(x_i\), i denotes the ith hyper-rectangle, and j denotes the jth data point in the hyperrectangle. In Equation (17), s denotes the total number of hyperrectangles explaining the clustered dataset, n denotes the total number of data points in the current hyperrectangle, and \(\rho _{i}\) denotes the density of the ith hyperrectangle, mentioned in Formula (7).

TPR (True Positive Rate)

TPR is also known as Sensitivity or Recall and measures the proportion of actual positive samples correctly identified as positive by a classification model. It is the ratio of True Positives (TP) to the sum of True Positives and False Negatives (FN). TPR quantifies the ability of a model to identify positive samples from the total actual positive samples. A higher TPR indicates better performance in correctly identifying positive samples. The formula is:

FPR (False Positive Rate)

It quantifies the proportion of negative samples that are incorrectly classified as positive by a classification model. It is the ratio of False Positives (FP) to the sum of False Positives and True Negatives (TN). FPR measures the model’s tendency to classify negative samples as positive. Lower FPR values indicate better performance in avoiding misclassification of negative samples. The formula is:

We consider two explanatory clustering algorithms, DReaM23 and ExKMC40, and the traditional CART41. In addition, to demonstrate the importance of pruning, we deliberately split the algorithm into un-MHR and MHR to compute the metrics separately. Where un-MHR denotes the result without a pruning operation and MHR is the algorithm with the complete process. We use the same fixed algorithmic parameters for all methods, and the same dbscan clusters or true labels as the reference cluster assignments we want to explain.

DReaM interprets clusters by establishing rules. One of its advantages is that two types of features can be randomly specified, rule-generated features and cluster structure-preserving features. In the DReaM model, rule-generated features generate explanations of clusters, while cluster structure-preserving features identify cluster structures. In addition, the model allows combining prior knowledge to adjust the final hyperrectangular decision boundary.

ExKMC interprets clusters with an IMM tree with k leaves. Subsequently, these k nodes expand to \(k_0\) nodes through a greedy search process. It minimizes the cost at each split and uses each node of the tree as the final explanations.

CART is an algorithm that builds decision trees for classification and regression tasks. It divides data into subsets based on feature values, creating a tree structure in which each node represents a decision rule that leads to predictions at the leaf nodes.

The following Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 show the metrics performance of our algorithm and other explanatory algorithms on different datasets, and the best experimental result values are bolded in the table.

Our empirical results on the different datasets offer insight into MHR’s performance against existing methods, including traditional approaches such as k-means, density-based, and hierarchical algorithms42. We also report results concerning other interpretable methods. Overall, our proposed method outperforms most algorithms on different verification criteria. Our experiments demonstrate that our newly proposed framework achieves comparable performance to the state-of-the-art clustering algorithms regarding clustering quality metrics while enabling the explicit characterization of cluster membership. Our model is robust to noisy or incomplete data while interpreting clusters. For discrete points in a rectangle that deviate from the data center, the model always finds an optimal cut line to perform a pruning operation on the rectangle. Thus, un-MHR is mostly optimal on clustering metrics, while MHR is the highest on interpretive scores. Therefore, we accept a slight reduction in the clustering criteria in exchange for increased interpretability, which is critical in many settings.

Discussion

MHR uses hyperrectangles that provide explicit separations of the data on the original feature set. It creates interpretable models with real-world applicability to a wide range of settings. From healthcare to revenue management to macroeconomics, our algorithm can significantly benefit practitioners who find value in unsupervised learning techniques.

We observe significant improvements in MHR relative to other interpretable methods. The multi-hyperrectangle interpretation algorithm better recognizes the shape of irregular clusters and finds the optimal number of hyperrectangles based on the hierarchical tree structure. It demonstrates the practicality of our approach rather than simply employing existing tree-based methods on a posteriori clustered data. Furthermore, our algorithmic approach improves existing work on interpretable clustering and makes a new contribution to the field.

Data availability

The data used in this paper includes both synthetic and real datasets, where the synthetic dataset can be obtained from https://cs.uef.fi/sipu/datasets/ and the real dataset from the UCI data web page https://archive.ics.uci.edu/.

References

Hou, B. et al. Deep clustering survival machines with interpretable expert distributions. In 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), 1–4 ( IEEE, 2023).

Horel, E. & Giesecke, K. Computationally efficient feature significance and importance for machine learning models. arXiv preprint arXiv: 1905.09849 ( 2019).

Alelyani, S., Tang, J. & Liu, H. Feature selection for clustering: A review. Data Clustering 29–60 ( 2018).

Horel, E., Giesecke, K., Storchan, V. & Chittar, N. Explainable clustering and application to wealth management compliance. In Proceedings of the First ACM International Conference on AI in Finance, 1–6 ( 2020).

Ellis, C. A., Sancho, M. L., Sendi, M. S., Miller, R. L. & Calhoun, V. D. Exploring relationships between functional network connectivity and cognition with an explainable clustering approach. In 2022 IEEE 22nd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE), 293–296 ( IEEE, 2022).

Peng, X. et al. Xai beyond classification: Interpretable neural clustering. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 23, 1–28 (2022).

Kauffmann, J. et al. From clustering to cluster explanations via neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. ( 2022).

Yao, Y. & Joe-Wong, C. Interpretable clustering on dynamic graphs with recurrent graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence Vol. 35, 4608–4616 (2021).

Effenberger, T. & Pelánek, R. Interpretable clustering of students’ solutions in introductory programming. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, 101–112 ( Springer, 2021).

Valdivia Orellana, R. M. Algorithm for interpretable clustering using dempster-shafer theory. ( 2024).

Jiang, D., Tang, C. & Zhang, A. Cluster analysis for gene expression data: a survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 16, 1370–1386 (2004).

Gunning, D. et al. Xai-explainable artificial intelligence. Sci. Robot. 4, eaay7120 (2019).

Goodman, B. & Flaxman, S. European union regulations on algorithmic decision-making and a “right to explanation’’. AI Mag. 38, 50–57 (2017).

Carrizosa, E., Kurishchenko, K., Marín, A. & Morales, D. R. On clustering and interpreting with rules by means of mathematical optimization. Comput. Oper. Res. 154, 106180 (2023).

Bhatia, A., Garg, V., Haves, P. & Pudi, V. Explainable clustering using hyper-rectangles for building energy simulation data. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Vol. 238, 012068 ( IOP Publishing, 2019).

Saisubramanian, S., Galhotra, S. & Zilberstein, S. Balancing the tradeoff between clustering value and interpretability. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, 351–357 ( 2020).

Wang, X., Liu, X. & Zhang, L. A rapid fuzzy rule clustering method based on granular computing. Appl. Soft Comput. 24, 534–542 (2014).

Mansoori, E. G. Frbc: A fuzzy rule-based clustering algorithm. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 19, 960–971 (2011).

Prabhakaran, K., Dridi, J., Amayri, M. & Bouguila, N. Explainable k-means clustering for occupancy estimation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 203, 326–333 (2022).

Champion, C., Brunet, A.-C., Burcelin, R., Loubes, J.-M. & Risser, L. Detection of representative variables in complex systems with interpretable rules using core-clusters. Algorithms 14, 66 (2021).

Rajab, S. Handling interpretability issues in anfis using rule base simplification and constrained learning. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 368, 36–58 (2019).

Pelleg, D. & Moore, A. Mixtures of rectangles: Interpretable soft clustering. In ICML Vol. 2001, 401–408 (2001).

Chen, J. et al. Interpretable clustering via discriminative rectangle mixture model. In 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), 823–828 ( IEEE, 2016).

Laber, E., Murtinho, L. & Oliveira, F. Shallow decision trees for explainable k-means clustering. Pattern Recogn. 137, 109239 (2023).

Kokash, N. & Makhnist, L. Using decision trees for interpretable supervised clustering. SN Comput. Sci. 5, 1–11 (2024).

Ghattas, B., Michel, P. & Boyer, L. Clustering nominal data using unsupervised binary decision trees: Comparisons with the state of the art methods. Pattern Recogn. 67, 177–185 (2017).

Moshkovitz, M., Dasgupta, S., Rashtchian, C. & Frost, N. Explainable k-means and k-medians clustering. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 7055–7065 (PMLR, 2020).

Gabidolla, M. & Carreira-Perpiñán, M. Á. Optimal interpretable clustering using oblique decision trees. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 400–410 ( 2022).

Laber, E. S. & Murtinho, L. On the price of explainability for some clustering problems. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 5915–5925 (PMLR, 2021).

Chaudhuri, D. & Samal, A. A simple method for fitting of bounding rectangle to closed regions. Pattern Recogn. 40, 1981–1989 (2007).

Toussaint, G. T. Solving geometric problems with the rotating calipers. In Proc. IEEE Melecon Vol. 83, A10 (1983).

Nemirko, A. & Dulá, J. Machine learning algorithm based on convex hull analysis. Procedia Comput. Sci. 186, 381–386 (2021).

Gamby, A. N. & Katajainen, J. Convex-hull algorithms: Implementation, testing, and experimentation. Algorithms 11, 195 (2018).

Eddy, W. F. A new convex hull algorithm for planar sets. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. (TOMS) 3, 398–403 (1977).

Asuncion, A. & Newman, D. Uci machine learning repository ( 2007).

De Lorenzi, C., Franzoi, M. & De Marchi, M. Milk infrared spectra from multiple instruments improve performance of prediction models. Int. Dairy J. 121, 105094 (2021).

Li, Y., Qi, J., Chu, X. & Mu, W. Customer segmentation using k-means clustering and the hybrid particle swarm optimization algorithm. Comput. J. 66, 941–962 (2023).

Yin, L., Li, M., Chen, H. & Deng, W. An improved hierarchical clustering algorithm based on the idea of population reproduction and fusion. Electronics 11, 2735 (2022).

Wei, S. et al. Unsupervised galaxy morphological visual representation with deep contrastive learning. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 134, 114508 (2022).

Frost, N., Moshkovitz, M. & Rashtchian, C. Exkmc: Expanding explainable \(k\)-means clustering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.02399 ( 2020).

Lewis, R. J. An introduction to classification and regression tree (cart) analysis. In Annual meeting of the society for academic emergency medicine in San Francisco, California, Vol. 14 (Citeseer, 2000).

Lawless, C. & Gunluk, O. Cluster explanation via polyhedral descriptions. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 18652–18666 ( PMLR, 2023).

Acknowledgements

This paper is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China(No. 62172242); Ningbo Key Laboratory of Intelligent Appliances, College of Science and Technology, Ningbo University; Zhejiang Province’s 14th Five Year Plan Teaching Reform Project(jg20220738); Ningbo Science and Technology Fund (2023Z228, 2023Z213, 20215070); Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project(22NDJC127YB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z.: experimental work, methodology, wrote the main manuscript text. C.Z: Writing-review and editing, supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, T., Zhong, C. & Pan, T. Clustering explanation based on multi-hyperrectangle. Sci Rep 14, 30260 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81141-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81141-3