Abstract

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is more common in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy. Some of these patients experience PTSD due to early psychotraumatic events. This study aims to assess the influence of PTSD on interictal functional connectivity using stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) recordings in patients with temporal lobe DRE (TDRE). Two groups were considered: TDRE patients with PTSD (PTSD+, N = 11) and TDRE patients without PTSD (PTSD-, N = 12). All subjects had questionnaires measuring anxiety, depression, PTSD symptoms related to seizures, a diagnostic PTSD questionnaire, and a childhood trauma questionnaire. Resting state functional connectivity (FC) was evaluated on SEEG signals to analyze network characteristics. We mainly focused on brain regions involved in PTSD (amygdala, orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, insula, rhinal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex). Results revealed increased FC in PTSD + subjects in the brain regions involved in PTSD, but only in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the epileptogenic zone. In contrast, a decreased FC in the contralateral hemisphere was observed in the hippocampus. These findings support the existence of a PTSD-epilepsy-reinforced network, leading to FC alterations dependent on the epilepsy side and the region. Our study is the first to offer insights into the intricate dynamic linking PTSD and epilepsy and highlights the need for accounting for the influence of comorbidities on epileptogenic networks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding epilepsy, particularly drug-resistant epilepsy, requires consideration of the impact of stressful psychotraumatic events. Research in animals suggests that stress experienced postnatally1 or later in life2 can contribute to depressive disorders and increase susceptibility to epileptogenesis. In human patients with epilepsy, there’s a higher incidence of psychotrauma, correlated with psychiatric comorbidity3. Specifically, patients with drug-resistant temporal epilepsy exhibit a heightened prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), possibly linked to past psycho-traumatic events or the traumatic nature of seizures themselves4. This association is accompanied by changes in cerebral metabolism with a pronounced hypometabolism in the right temporal pole and amygdala region5. Thus, there might be a significant interplay between PTSD and temporal epilepsy-specific alterations.

Alterations in cerebral networks can be studied using cerebral connectivity measurements in imaging or electrophysiology. In PTSD, functional connectivity studies have shown abnormalities, particularly an increase in the connectivity of certain regions involved in the regulation of fear (amygdala, prefrontal cortex, cingulate gyrus) but also in the default mode network and other regions that may be involved in dissociation6. Drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) is recognized as network disease7 characterized, in the interictal period, by an increase in the functional connectivity of the regions involved in seizure genesis and propagation8. It is conceivable that the coexistence of PTSD and drug-resistant epilepsy could amplify the connectivity alterations typically seen when these conditions occur independently.

This study aimed to compare functional connectivity measured from SEEG signals in patients with temporal drug-resistant epilepsy (TDRE) with and without PTSD to elucidate the association between PTSD and epilepsy. Based on existing literature, we anticipate observing connectivity differences in PTSD-related regions among PTSD patients with and without PTSD.

Materials and methods

Patients and psychological evaluation

We retrospectively studied a cohort of patients with SEEG recordings between 2018 and 2022 for presurgical evaluation of drug-resistant temporal epilepsy within the Department of Epileptology, Timone Hospital (Marseille, France). The definition of drug resistance was done according to the ILAE criteria, in particular the failure of at least two anti-seizure medication (ASM)9. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and all procedures were approved by the Assistance Publique - Hopitaux de Marseille institutional review board. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Research has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

All selected patients had questionnaires and evaluations of their psychiatric status during their presurgical evaluation, including PTSD evaluation.

Patients were categorized into two groups: patients with PTSD (PTSD+) and patients without PTSD (PTSD-). Inclusion criteria for patients with PTSD were as follows: (i) diagnosis of temporal epilepsy, (ii) presenting with a diagnosis of PTSD at the psychological interview and on the PCL-5 and CTQ scales, and (iii) having been repeatedly exposed to trauma in childhood. Patients without PTSD (PTSD-) should not have been exposed to a particularly traumatic event and not have shown clinical symptoms of PTSD. The description of the two groups is presented in Table 1.

Patients completed a series of questionnaires following a psychological interview to obtain variables dependent on psychiatric and psycho-affective symptoms:

-

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7): for generalized anxiety screening, we used the French version of the GAD-7 scale with a cutoff score of 7/21 10.

-

Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E): for major depressive disorder screening, we used the French version of the NDDI-E scale with a cutoff score of 15/24 10.

-

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder for Epilepsy (PTSD-E): this scale has already been used in previous studies by the team4,5,11 to evaluate the symptoms during the inter- and peri-ictal period. We investigated whether seizures could be triggered by trauma-related thoughts (specificity), avoidance behaviors, hypervigilance about the risk of having a seizure (over-alert state); intrusive thoughts (emotions or memories) during the ictal period, and psychological distress that could result from these symptoms in the postictal period. The questionnaire items were scored as categorical variables ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always) to create total and sub-scale scores. These questionnaires have been designed in such a way that the higher the patient’s score, the more likely it is that PTSD symptoms are linked to episodes during seizures.

-

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)12 : it is the only French-validated questionnaire to measure the symptoms of PTSD as defined by the DSM-5. It has been determined that a score higher than 31 indicates the presence of PTSD.

-

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): to assess maltreatment experiences by family members from childhood until age 18, we used a short version of the CTQ scale, validated in French. This scale comprises five subscales, each with its cutoff: emotional neglect (≥ 16), emotional abuse (≥ 16), physical abuse (≥ 11), sexual abuse (≥ 11) and physical neglect (≥ 14). All subscale scores range from 5 (no maltreatment experience) to 25 (severe maltreatment experience).

SEEG recordings and preprocessing

SEEG signals were recorded on a Natus system (Natus Medical Incorporated Pleasanton, California, USA) with a 1024 Hz sampling rate and a 16-bit resolution. The system included a hardware high-pass filter (cut-off 0.16 Hz) and an antialiasing low-pass filter (cut-off 340 Hz). Signals from each contact were manually inspected one by one to exclude artifacts and noise, thanks to the AnyWave software13. For each patient, a bipolar montage including all contacts within the gray matter was automatically generated using GARDEL software14. GARDEL generates personalized 3D maps of the implanted SEEG electrodes and AnyWave-compatible grey matter montages based on the co-registration of the pre-implantation T1-MRI with post-implantation CT images, followed by automatic recognition and anatomical localization of each electrode contact. Co-registration of the pre-implantation T1-MRI with post-implantation CT images was performed, followed by an automatic recognition and anatomical localization of each electrode contact, which was then automatically assigned automatically to the respective anatomical region of the VEP atlas projected in the patient’s MRI space15.

To evaluate network changes in TDRE subjects with and without PTSD, SEEG segments lasting 10 min were manually chosen during resting state (manually marked by the neurologist). Functional connectivity (FC) analysis for each patient was performed in four frequency sub-bands (delta: 1–4 Hz, theta: 4–8 Hz, alpha: 8–15 Hz, beta: 15–30 Hz) and broadband (1–45 Hz). To avoid connectivity biases and oversampling, we excluded adjacent bipolar contacts in the selected montage.

To analyze network characteristics, resting state FC was evaluated on SEEG traces via the linear (R2, for sub-bands) and the nonlinear (h², for broadband) correlation coefficients between each couple of contacts, representing nodes of the network16,17,18.

The nonlinear correlation coefficient h² measures nonlinear regression and takes values in the interval [0, 1]. Low values of h² denote that the two analyzed signals are uncorrelated (both linearly and nonlinearly). High values of h² indicate that at least one of the two signals may be explained by a piecewise linear transformation of the other17. From the R2 and h2 connectivity matrices, we calculated the node strength of each contact by summing all the links and normalizing them by the number of contacts to avoid the influence of varied numbers of contacts couples across patients.

We chose to focus on the brain regions which have previously been demonstrated to be involved in traumatic memory processing19,20,21. Among them, each subject included in our study presented at least one electrode inserted inside either the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the hippocampus, the insula, the rhinal cortex, or the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).

We also estimated whether patients with PTSD diagnosis presented different epileptogenicity profiles in the recorded regions. We used quantitative SEEG-signal analysis using the Epileptogenicity Index (EI) method22. The EI combines analysis of both spectral and temporal features of SEEG signals, respectively, related to the propensity of a brain area to generate fast discharges (12.4–127 Hz) and to the earliness of involvement of this area in the seizure. A normalized EI value, ranging from 0 (no epileptogenicity) to 1 (maximal epileptogenicity) was used for each considered structure (for detailed methodology see22,23). In each patient, maximal EI values from two representative seizures were computed for bipolar SEEG contacts.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed in MATLAB (Mathworks, Naticks, MA; version R2022b) and R (version 4.2.2). Connectivity matrices were calculated in Anywave13 and were further processed in MATLAB to create a node strength table containing one row per contact for each subject. For the analysis of different regions pooled together, FC values from the same structure were averaged for each subject before calculating the node strength of that structure. For single structures analysis, we considered all contacts from each subject without averaging them. Contacts were separated into ipsilateral and contralateral, depending on their location concerning the seizure onset hemisphere (e.g., in a subject with right-lobe seizure onset, a contact in the right amygdala was defined as ipsilateral; a contact in the left amygdala was defined as contralateral). In further analyses of group differences, patients were categorized into right-lobe and left-lobe seizure onset. Differences between the PTSD + and the PTSD- groups were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons. P-values were complemented by Cohen’s d to measure the effect size of our comparisons. A Cohen’s d effect size is defined as: “negligible” if |d| < 0.2, “small” if |d| < 0.5, “medium” if |d| < 0.8, otherwise “large”24. Finally, the correlation between FC and questionnaire scores was tested via Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Results

Clinical data

We studied 23 patients with TLE (Table 1). Descriptive results for the clinical scales are presented in Table 2. Several participants reported having experienced multiple traumatic events during childhood. PTSD + group includes 12 patients who experienced repeated traumatic events during childhood and who still exhibit PTSD symptoms. (Consistent with the diagnostic scales and the psycho-clinical interview). Since levetiracetam (LTV) may alter mood and suicidal thoughts, we have compared the two groups in terms of ASM. We did not find differences between the two groups in the use of LTV (χ2 (1,N = 23) = 24,21,p = 0,28). In addition, the number of ASM was not different in the two groups (t(19) = 0,74), p = 0,466).

Differences in epileptogenicity

We first investigated whether patients with PTSD diagnosis presented stronger epileptogenicity in the recorded regions, which are known to be involved in traumatic memory processing (defined in the method section). When calculating the average epileptogenicity index for each region in either the left or right hemisphere (Supplemental. Figure 1), we did not observe significant differences between the PTSD + and PTSD- groups except for a trend (p = 0.056) for stronger EI in the amygdala of PTSD + subjects.

Functional connectivity: comparison of the PTSD network

The study’s first objective was to identify potential differences across all regions recorded via SEEG. First, we performed a statistical comparison for the pooled regions in PTSD + against PTSD- subjects. When considering all regions pooled together (node strength average per region of each subject), PTSD + patients showed significantly stronger broadband node strength than PTSD- patients (p = 3.4e-09, d = 0.4). Functional connectivity characteristics in the broadband may reflect more narrow band changes in sub-bands. For this reason, we investigated potential FC differences between PTSD + and PTSD- patients in four EEG sub-bands. For patients with right-lobe seizure onset, FC was stronger in the PTSD + group in all bands except for delta and theta. On the contrary, in patients with left-lobe onset, FC was significantly stronger in the PTSD + group only in delta and alpha bands (Table 3). None of the bands exhibited stronger FC in PTSD- compared to PTSD + patients.

Although interesting for a first overview of the connectivity profiles in PTSD, brain-wide FC differences between PTSD + and PTSD- patients should be more thoroughly investigated inside the brain regions known to be involved in PTSD. We thus focused on the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the hippocampus, the insula, the rhinal cortex, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), chosen based on previous studies reporting a correlation between activity alteration in such regions and PTSD19,20,21. These regions were called “involved regions” in the following.

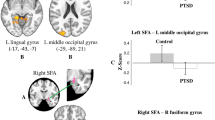

Node strengths from all the involved regions (one region per subject) were thus pooled together, and regions were separated between ipsilateral and contralateral, depending on their location regarding the seizure onset hemisphere. Figure 1 shows that the network of involved regions in PTSD + subjects is more strongly connected to other brain regions than in PTSD- patients. This result holds only for involved regions ipsilateral to the EZ (Fig. 1A) but not for regions contralateral to the EZ, which show no significant difference between groups (Fig. 1B). When investigating the intra-network connectivity (FC inside the involved regions and not with other recorded areas), we found no difference either ipsilaterally or contralaterally to the EZ.

Broadband (1–45 Hz) node strength in PTSD + vs. PTSD- patients, in involved network. Involved PTSD regions consist in: amygdala, hippocampus, rhinal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, orbitofrontal cortex, and node strength was calculated from connections to all other regions (also outside the involved network). (A) Resting state total node strength (sum of out- and in-going links) of FC in PTSD- subject (light yellow) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark yellow) for regions located ipsilaterally to the EZ. (B) Resting state total node strength of FC in PTSD- subject (light blue) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark blue) for regions located contralaterally to the EZ.

FC differences in specific structures

Involved regions show a general increase of FC in PTSD + patients. To understand whether all involved brain areas show this property, each region of the involved network was tested separately. Since contralateral regions do not present the same FC results as ipsilateral regions, we kept this categorization for the following analyses. Moreover, FC in each region was tested against three different sets of regions: (i) all other recorded regions, (ii) only inside the involved network of regions, (iii) between the region and the available contacts considered to be non-involved in PTSD (inferior and superior temporal sulcus, temporal lobe T1, T2, and T3). The results of the statistical comparisons for each band and brain region are summarized in Supp—Table 1.

The SEEG contacts in the contralateral amygdala, insula, OFC, rhinal cortex, and ACC either showed no significant difference between groups or were not evaluated statistically due to insufficient implanted electrodes. The following results thus refer to nodes located ipsilaterally to the EZ. As observable in Fig. 2A, contacts in the ipsilateral amygdala showed a stronger node strength in PTSD + patients in broadband, but only when considering connections between the amygdala and other non-involved regions (p < 0.05, d = 0.8). The same result was found in the theta band (Supp. Table 1). Interestingly, the beta and low gamma bands showed lower FC of the amygdala against other involved regions (beta: p < 0.05, d=-0.8, low gamma: p < 0.01, d=-0.9). Regarding contacts located in the ipsilateral insula (Fig. 2B), node strength was higher in broadband for all connections with other brain areas (p < 0.01, d = 0.7), for connections inside the involved network (p < 0.01, d = 0.8) and between the involved and the non-involved network (p < 0.05, d = 0.8). Ipsilateral OFC showed the same more robust connectivity in PTSD + subjects (Fig. 2C for broadband, OFC vs. all other regions: p < 0.01, d = 1.1; vs. involved network: p < 0.05, d = 0.7, vs. non-involved network: p < 0.001, d = 1.3). This was only valid for the broadband as no significant difference was found in other bands (Supp. Table 1). The FC of the ipsilateral rhinal cortex also presented stronger node strength in PTSD + subjects in broadband (Fig. 2D), but only inside the involved network (p < 0.05, d = 0.6) and with non-involved regions (p < 0.001, d = 0.8). The same was found in the delta and theta bands, with only a significant difference in connectivity between the rhinal cortex and non-involved regions in the alpha band (Supp. Table 2). The ipsilateral ACC showed more variable FC differences, resulting in an increased node strength in PTSD + subjects in the alpha band but a decreased node strength in theta, low gamma, and broadband. In broadband, the node strength in the ACC was weaker in PTSD + subjects inside the involved network only (p < 0.01, d=-1.8).

Node strength in PTSD + vs. PTSD- patients in ipsilateral PTSD involved regions, broadband (1–45 Hz). The three boxplot columns represent the resting state node strength for each region in each subject calculated respectively: with all other brain regions (“all connections”), within the involved network (“inside involved network”), and between each involved region and other regions that are supposed not to be involved in PTSD (“involved-non-inv”). (A) total node strength of amygdala contacts in PTSD- subject (light blue) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark blue). (B) total node strength of insula contacts in PTSD- subject (light green) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark green). (C) total node strength of orbitofrontal cortex contacts in PTSD- subject (light orange) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark orange). (D) total node strength of rhinal cortex contacts in PTSD- subject (light purple) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark purple). P-values were coded as follows: *= p < 0.05, **=p < 0.01, ***=p < 0.001.

The ipsilateral hippocampus did not show any significant FC strength difference between PTSD + and PTSD- patients (Fig. 3A), but the SEEG contacts in the contralateral hippocampus showed a weaker FC in PTSD + subjects (Fig. 3B). The difference was present when considering all connections with other recorded brain areas (p < 0.01, d=-0.7) and was even more marked when considering intra-network connections within involved regions (p < 0.001, d=-1.2).

Node strength in PTSD + vs. PTSD- patients in the hippocampus, broadband (1–45 Hz). The three boxplot columns represent the resting state node strength the hippocampus calculated respectively: with all other brain regions (“all connections”), within the involved network (“inside involved network”), and between each involved region and other regions that are supposed not to be involved in PTSD (“involved-non-inv”). (A) total node strength of the hippocampus located ipsilaterally to the EZ in PTSD- subject (light yellow) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark yellow). (B) total node strength of the hippocampus contacts located contralaterally to the EZ in PTSD- subject (light yellow) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark yellow). P-values were coded as follows: **p < 0.01, ***=p < 0.001.

After quantifying connectivity differences in ipsilateral and contralateral involved regions, we further investigated whether the laterality of the seizure onset network (right, left, or bilateral) could influence FC in the involved network. Although ipsilateral amygdala contacts pooling right- and left-lobe epilepsy subjects did not show any significant difference in connectivity with all other regions (Fig. 2A, first column), we found a strong trend of higher FC in the right amygdala of PTSD + subjects with right-lobe seizure onset compared to the right amygdala of PTSD- subjects (Fig. 4A, p = 0.053, d=-1.2). The same result was found in alpha, theta, and delta bands (Supp. Table 2). Regarding channels located in the insula (Fig. 4B), node strength was higher in broadband for both right- and left-lobe seizure onset PTSD + patients (right-lobe onset: p < 0.01, d = 1.1, left-lobe onset: p < 0.01, d = 0.9). On the other hand, contacts in the orbitofrontal cortex displayed stronger connections in PTSD + patients in broadband, which was significant (Fig. 4C, p < 0.05, d = 1.3) only in patients with left-lobe seizure onset (probably due to a lack of data points in right-lobe epilepsy subjects). Similarly, contacts located in the rhinal cortex showed stronger FC strength only in left-lobe onset PTSD + patients in broad, delta, and theta bands.

Node strength in PTSD + vs. PTSD- patients, specific structures. (A Resting state total node strength of amygdala contacts only in PTSD- subject (light blue) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark blue) in broadband (1–45 Hz) for all contacts against each other in right-lobe seizure onset patients (p = 0.053, d = 1.2) and left-lobe seizure onset patients (ns). (B) Broadband total node strength of insula contacts only in PTSD- subject (light green) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark green) for all insula contacts in right-lobe seizure onset patients (p = 0.001, d = 1.1) and left-lobe seizure onset patients (p = 0.001, d = 0.9). (C) Broadband total node strength of orbito-frontal cortex contacts only in PTSD- subject (light orange) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark orange) in right-lobe seizure onset patients (ns) and left-lobe seizure onset patients (p = 0.031, d = 1.3).

Differences in default mode network connectivity

Following the findings of altered activity in default mode network (DMN) regions in PTSD6, we investigated whether functional connectivity in DMN-associated brain areas presented differences between PTSD + and PTSD- subjects. In our dataset, subjects were implanted for mesio-temporal lobe epilepsy investigation, thus limiting the number of implanted regions involved in the DMN. Among the recorded regions, the following were included in the DMN analysis: the parahippocampal cortex, temporal regions, the hippocampus, the posterior cingulate cortex, the precuneus, the insula, the medial prefrontal cortex, the inferior parietal lobule. When investigating the pooled node strength in these regions against all channels (Fig. 5A), we found stronger FC in PTSD + subjects compared to PTSD- subjects (p < 0.05, d = 0.4). To avoid the potential influence of PTSD-related regions in this result, we repeated the analysis, excluding the regions involved in PTSD (insula and hippocampus). We found an even stronger FC in PTSD + subjects (Fig. 5B), also present when investigating connections inside this network (Supp. Figure 2, left).

Node strength in default mode network (DMN), central executive network (CEN) and in neutral regions. All results presented here refer to broadband (1–45 Hz) and to connection with all other recorded regions. (A) Resting state total node strength of DMN regions in PTSD- subject (light yellow) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark yellow). (B) Resting state total node strength of DMN regions without hippocampus and insula in PTSD- subject (light yellow) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark yellow). (C) Resting state total node strength of CEN regions (premotor cortex, superior frontal sulcus) in PTSD- subject (light blue) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark blue). (D) Resting state total node strength of regions not involved in DMN, CEN nor PTSD (lateral temporal lobe, inf. and sup. temporal sulcus) in PTSD- subject (light grey) compared against PTSD + subjects (dark grey). P-values: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

We repeated the same analysis on two different region selections to test whether these differences were proper to regions implied in the DMN. Firstly, we considered regions (premotor cortex F2, superior frontal sulcus) belonging to the central executive network (CEN), which is known to generally show the opposite activity to the DMN25. We found no significant differences between PTSD + and PTSD- subjects in connections with all recorded regions (Fig. 5C) nor inside the CEN network (Supp. Figure 2, right). Secondly, we selected “neutral” regions that are usually not associated with either the DMN, CEN, salience network, or PTSD. The previous paragraphs used these regions (inferior and superior temporal sulcus, temporal lobe T1, T2, and T3) as “non-involved” networks. As expected, we did not find any significant differences in the node strength of these regions when comparing PTSD + against PTSD- subjects (Fig. 5D).

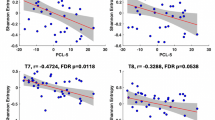

Correlation between FC and questionnaire scores

Alterations in functional connectivity of the brain regions involved in PTSD might be related to the severity of PTSD or other comorbidities. We calculated the Spearman correlation between node strength and the main mental health scores (GAD-7, NNDI-E, PCL-5) for each area to test this relationship. We furthermore included the new score of PTSD-E along with the other main indexes to explore its potential to correlate with PTSD functional connectivity alterations. We found no significant correlation between the amygdala, OFC, and ACC scores and FC node strength values. However, as visible in Fig. 6, the broadband node strength in the (contralateral and ipsilateral) insula and the rhinal cortex presented a positive correlation with the PTSD-E score exclusively (insula: r = 0.31, p < 0.05; rhinal cortex: r = 0.38, p < 0.05).

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate FC changes in patients with PTSD associated with PTSD following childhood trauma. We aimed to observe whether there were differences in resting-state brain network organization in PTSD patients with PTSD from early trauma compared to PTSD patients not diagnosed with PTSD.

The PTSD + patients generally showed significantly stronger broadband node strength than PTSD- patients. This was observed when pooling all recorded SEEG contacts and in regions involved in PTSD located ipsilateral to the EZ. At the same time, no significant difference was found in the epileptogenicity levels of PTSD + vs. PTSD- subjects. Contralateral regions did not show any FC difference between groups, except for the hippocampus, where we found weaker connectivity in PTSD + subjects. The ipsilateral insula, OFC, rhinal cortex, and amygdala showed stronger FC in broadband, and this result depended on the laterality of epilepsy. Notably, only the right amygdala in right-lobe epilepsy patients – but not the left one in left-lobe epilepsy patients - showed an almost significantly stronger FC in PTSD + subjects compared to PTSD- subjects. Moreover, we found a higher FC in the DMN of PTSD + subjects. Our results corroborate the hypothesis that PTSD in epilepsy may be linked to substantial alterations in the organization of brain networks.

The relationship between epilepsy and neural network alteration is well-established nowadays; increased FC in temporal lobe networks and the EZ hemisphere has been observed in several SEEG studies8,26,27. On the other hand, studies investigating FC changes in PTSD are rare and limited to neurofunctional imaging. These studies have so far demonstrated that PTSD is associated with an increased FC in the fear-processing regions, particularly the amygdala, and a decreased FC in the control networks20,28,29. Recurrent activation of traumatic memories is believed to reinforce the neural network associated with fear responses, making it more robust and harder to disrupt30. This repetitive recall could also potentially enhance connectivity within the epileptogenic network, which is the group of brain regions responsible for generating and propagating seizures. Our findings suggest this may be the case, as we observed increased FC in the brain regions on the same side as the EZ, indicating that trauma-related neural activity might strengthen pathways that contribute to seizure generation. This suggests that PTSD may contribute to or exacerbate network alterations in epilepsy. However, our findings are correlational, and while they underscore an interplay between epilepsy and fear networks, they do not imply direct causation.

The FC differences in the amygdala are more marked in patients whose seizure onset comes from the right hemisphere, not the left hemisphere. This hemispheric specificity of PTSD in epilepsy had already been observed in one of our previous publications5. Indeed, in a recent metabolic FDG-PET study, we showed that PTSD + patients present a right medial polar temporal hypometabolism that spreads over the amygdala and orbitofrontal region. Moreover, the PTSD + patients in that study had been selected in the same way (PTSD following childhood trauma) and showed a higher percentage of right-lobe seizure onset compared to PTSD- patients5. This right temporal prominence was also observed in a study showing a preferential alteration in the volume of the right temporal pole in subjects suffering from PTSD31.

In the present work, we found FC changes proper to the brain structures involved in PTSD, particularly an increase in the amygdala consistent with models of PTSD19,20,21. We moreover replicated some previous findings regarding hyper-activation of the DMN regions in patients with PTSD, which presents variable results in imaging studies21,25.

Communication between the amygdala and the hippocampus has been proposed to support emotional memory. Thanks to intracranial recordings in pre-surgical epilepsy patients, Zheng et al.32have studied the neural mechanisms underlying the precision of memory retrieval, specifically of the discrimination of overlapping experiences in memory, which tend to deteriorate over time32. The authors postulate that the theta band in the amygdala allows for the correct location of emotional recollection in time (discrimination of an old or new stimulus). In contrast, increased alpha band synchrony may impair the discrimination of similar emotional events via the amygdala-hippocampal directional coupling. Thus, reliving traumatic memories could be associated with poor amygdala-hippocampal theta coupling responsible for vividness and accuracy. This could be potentially reflected in the weaker theta band connectivity of the (contralateral) hippocampus with other involved areas in PTSD + subjects observed in our study. However, we also found weaker hippocampal intra-involved network connectivity in the alpha band. Furthermore, heightened activity in the amygdala, particularly in the alpha, theta, and delta bands, supports the hypothesis of amygdala hyperactivity in patients with PTSD from childhood trauma. The variations in hemispheric laterality within these frequency bands should likely be investigated by considering the network alterations specific to epilepsy.

The observed FC increase in the insula aligns with PTSD brain models, which assign to this region a key role in interoceptive awareness of emotional states33,34. Indeed, individuals with PTSD show activation in brain areas perceiving emotional states through interoception even when not consciously perceived35. The heightened insula response during exposure to adverse events is associated explicitly with symptoms such as reviviscence36, hyperarousal37, and the onset of flashbacks38. Consequently, the degree to which individuals with PTSD re-experience physical cues of their traumatic event may directly correlate with insula hyperactivity during emotional processing35. Consistent with this view, we found that FC in the insula positively correlates with the score of a recently developed questionnaire, the PTSD-E. The PTSD-E scale indicates whether PTSD symptoms may be linked to seizures and might thus be more specific for our dataset than other standard scores, such as the PCL-5.

This result, together with the fact that stronger FC was found in ipsilateral regions of the EZ, might indicate a potential link between the PTSD-related changes in FC in PTSD + subjects and epileptogenic network-related changes. Indeed, since epilepsy is accompanied by its neural network signatures, we may hypothesize that PTSD effects on epileptogenic networks do not perfectly reflect the PTSD effects on healthy brains.

Further comprehensive analyses are needed to better understand the influence of PTSD on epileptogenic networks. At a more local level, the role of different frequency bands could be investigated by studying the power spectral density of the involved regions. Analysis of the frequency content in various bands and regions might shed light on the variability of amygdala’s and ACC’s FC results in the investigated frequency bands. Moreover, our analysis was inherently limited by: (i) the implantation of SEEG electrodes in temporal areas, with few SEEG contacts in prefrontal areas, and (ii) the atlas used (VEP atlas15), which does not differentiate between dorsal and ventral ACC. Future studies, including more variable implantation and electrodes in the regions of interest, could lead to more robust statistical analysis and better differentiation between the brain areas and networks involved.

Finally, to better test the relationship between FC and questionnaire scores, more variables such as etiology, age, sex, and specific region could be considered. Although the patients were selected based on having been exposed to traumatic events in childhood and having PTSD, the majority of them reported having experienced several cumulative traumas of different kinds. Furthermore, sexual abuse (62%) was reported by most patients in our cohort before physical abuse (38%). The presence of a high percentage of early trauma in PTSD patients and of FC features associated with it underlies the importance of taking childhood trauma and PTSD into account when investigating epileptogenic networks.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates for the first time that there is a significant overlap between the network associated with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the network responsible for epileptic seizures, suggesting a potential mutual reinforcement.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Jones, N. C. & O’Brien, T. J. Stress, epilepsy, and psychiatric comorbidity: How can animal models inform the clinic? Epilepsy Behav. 26, 363–369 (2013).

Becker, C. et al. Predicting and treating stress-Induced vulnerability to epilepsy and depression. Ann. Neurol. 78, 128–136 (2015).

Labudda, K. et al. Psychiatric disorders and trauma history in patients with pure PNES and patients with PNES and coexisting epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 88, 41–48 (2018).

Soncin, L. et al. Epilepsy & Behavior post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 121, 108083 (2021).

Soncin, L. D. et al. Correlation between fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography brain hypometabolism and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 63, e74–e79 (2022).

Sripada, R. K. et al. Neural dysregulation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for disrupted equilibrium between salience and default mode brain networks. Psychosom. Med. 74, 904–911 (2012).

Bartolomei, F., Lagarde, S., Wendling, F. & Mcgonigal, A. Defining epileptogenic networks: Contribution of SEEG and signal analysis. 1131–1147 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.13791

Lagarde, S., Bénar, C. G., Wendling, F. & Bartolomei, F. Interictal functional connectivity in focal refractory epilepsies investigated by Intracranial EEG. Brain Connect. 12, 850–869 (2022).

Kwan, P. et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: Consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on therapeutic strategies. Epilepsia 51, 1069–1077 (2010).

Micoulaud-Franchì, J. A., Bartolomei, F., Duncan, R. & McGonigal, A. Evaluating quality of life in epilepsy: the role of screening for adverse drug effects, depression, and anxiety. Epilepsy Behav. 75, 18–24 (2017).

Soncin, L. D. et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), cognitive control, and perceived seizure control in patients with epilepsy: An exploratory study. Epilepsy Behav. 147, 109396 (2023).

Ashbaugh, A. R., Houle-Johnson, S., Herbert, C., El-Hage, W. & Brunet, A. Psychometric validation of the English and French versions of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PLoS One. 11, 1–16 (2016).

Colombet, B., Woodman, M., Badier, J. M., Bénar, C. G. & AnyWave A cross-platform and modular software for visualizing and processing electrophysiological signals. J. Neurosci. Methods. 242, 118–126 (2015).

Medina Villalon, S. et al. A software suite for presurgical brain mapping in epilepsy: Intracerebral EEG. J. Neurosci. Methods. 303, 7–15 (2018).

Wang, H. E. et al. VEP atlas: an anatomic and functional human brain atlas dedicated to epilepsy patients. J. Neurosci. Methods. 348, 108983 (2021).

Pijn, J. P. & da Lopes, F. Propagation of electrical activity: Nonlinear associations and Time delays between EEG signals. Basic. Mech. EEG. 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-0341-4_4 (1993).

Wendling, F., Bartolomei, F., Bellanger, J. J. & Chauvel, P. Identification De réseaux épileptogènes par modélisation et analyse non linéaire des signaux SEEG [Identification of epileptogenic networks from modeling and nonlinear analysis of SEEG signals]. Neurophysiol. Clin. 31, 139–151 (2001).

Lagarde, S. et al. Interictal stereotactic-EEG functional connectivity in refractory focal epilepsies. Brain 141, 2966–2980 (2018).

Lanius, R. A. et al. Emotion modulation in PTSD: clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. Am. J. Psychiatry. 167, 640–647 (2010).

Liberzon, I. & Abelson, J. L. Context Processing and the neurobiology of post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuron 92, 14–30 (2016).

Harnett, N. G., Goodman, A. M. & Knight, D. C. PTSD-related neuroimaging abnormalities in brain function, structure, and biochemistry. Exp. Neurol. 330, 113331 (2020).

Bartolomei, F., Chauvel, P. & Wendling, F. Epileptogenicity of brain structures in human temporal lobe epilepsy: a quantified study from intracerebral EEG. Brain 131, 1818–1830 (2008).

Makhalova, J. et al. The role of quantitative markers in surgical prognostication after stereoelectroencephalography. Ann. Clin. Transl Neurol. https://doi.org/10.1002/acn3.51900 (2023).

Sullivan, G. M. & Feinn, R. Using effect size—or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad Med. Educ. 4, 279 (2012).

Nicholson, A. A. et al. Classifying heterogeneous presentations of PTSD via the default mode, central executive, and salience networks with machine learning. Neuroimage Clin. 27, 102262 (2020).

Antony, A. R. et al. Functional connectivity estimated from intracranial EEG predicts surgical outcome in intractable temporal lobe epilepsy. PLoS One. 8, 1–7 (2013).

Bettus, G. et al. Enhanced EEG functional connectivity in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 81, 58–68 (2008).

Malivoire, B. L., Girard, T. A., Patel, R. & Monson, C. M. Functional connectivity of hippocampal subregions in PTSD: relations with symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 18, 129 (2018).

Haris, E. M., Bryant, R. A., Williamson, T. & Korgaonkar, M. S. Functional connectivity of amygdala subnuclei in PTSD: a narrative review. Mol. Psychiatry. 28, 3581–3594 (2023).

Parsons, R. G., Walker, D. L. & Davis, M. Neurobiology of learning and memory mechanisms underlying long-term fear memory formation from a metaplastic neuronal state. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 136, 47–53 (2016).

Gosnell, S. N. et al. Right temporal Pole volume reduction in PTSD. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 100, 109890 (2020).

Zheng, J. et al. Multiplexing of Theta and Alpha rhythms in the amygdala-hippocampal circuit supports pattern separation of emotional information. Neuron 102, 887–898e5 (2019).

Craig, A. D. B. How do you feel–now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nature reviews. Neuroscience vol. 10 59–70 Preprint at (2009). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2555

Grupe, D. W. & Nitschke, J. B. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: An integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 488–501 (2013).

Fitzgerald, J. M., Digangi, J. A., Phan, K. L. & Biology, C. U. S Department Veterans Affairs 26, 116–128 (2019).

Hopper, J. W., Frewen, P. A., van der Kolk, B. A. & Lanius, R. A. Neural correlates of Reexperiencing, Avoidance, and dissociation in PTSD: symptom dimensions and emotion dysregulation in responses to script-driven trauma imagery. 20, 251–262 (2007).

Simmons, A. N. et al. Functional activation and neural networks in women with posttraumatic stress disorder related to intimate Partner violence. Biol. Psychiatry. 64, 681–690 (2008).

Osuch, E. A. et al. Regional cerebral blood flow correlated with flashback intensity in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 50, 246–253 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof Agnes Trebuchon, MD, PhD; Stanislas Lagarde, MD, PhD; Dr. Francesca Pizzo, MD, PhD; Dr. Francesca Bonini, MD, PhD; Dr. Sandrine Aubert, MD; Dr. Aileen McGonigal, MD, PhD; Dr. Lisa Vaugier, MD, Dr Marie Arthuis and Miss Marine Cossettini for the clinical management of some included patients. We thank Pr Didier Scavarda and Dr Romain Carron for stereotactic EEG and surgical procedures.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LDS was primarily responsible for the conceptualization of the study, focusing in particular on theoretical aspects related to PTSD in epilepsy. She also contributed significantly to clinical data collection and she worked extensively on interpreting the results and co-wrote the manuscript.- SS was responsible for collecting and pre-processing the SEEG data. She carried out the functional connectivity analysis and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. - NH participated in collecting and organizing the SEEG data and contributed to the technical aspects of data processing. - HM participated in the collection of clinical data- MA provided clinical information and participated in the psychiatric management of the epilepsy patients involved in the study. She also participated in the collection of medical data and the interpretation of clinical results.- CB contributed to the data analysis methodology, providing expertise in SEEG signal processing and network analysis. - SF advised on the design of psychological assessments and interpreting psychiatric data. - FB supervised the entire project, from inception to manuscript preparation and data analysis. He provided clinical and methodological supervision, ensuring data integrity and analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript, provided critical comments, and approved the final version.Lisa-Dounia Soncin and Sara Simula’s scientific contributions to this study are equal and share co-first authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Soncin, LD., Simula, S., Hemmer, N. et al. Impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on epileptogenic networks: a functional connectivity study. Sci Rep 14, 31688 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81164-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81164-w