Abstract

Previous studies indicate differences in experiences of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic but are constricted by limited timeframes and absence of key risk factors. This study explores temporal and inter-individual variations of loneliness in Canadians over the pandemic’s first year (April 2020–2021), by identifying loneliness trajectories. It then seeks to provide information about groups overrepresented in high and persistent loneliness trajectories by examining their associations with risk factors: social isolation indicators (living alone, adherence to health measures limiting in-person contacts, and online contacts), young adultood, and the interactions between these factors. Data comes from a large longitudinal study with a representative Canadian sample (n = 1763) and 11 measurement times. Analyses consist of (1) a group-based modelling approach to identify trajectories of loneliness and (2) multinomial logistic regressions to test associations between risk factors and trajectory membership. Varied experiences of loneliness during the pandemic were revealed as five trajectories were identified: moderate-unstable (38.5%), high-stable (26.7%), low-unstable (20.5%), very low-stable (8.6%), and very high-decreasing (5.7%). Individuals living alone associated with higher trajectories. Contrary to our expectations, adhering to social distancing measures and having fewer online contacts associated with lower trajectories. Age and interactions were not significant in regard to loneliness trajectories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Loneliness is a significant public health concern associated with numerous physical and mental health problems, and increased mortality1. It is defined as the negative subjective experience resulting from a perceived gap between desired social contacts and actual social contacts2. As such, loneliness is not directly dependent on the quantity and quality of social contact, but rather is related to individuals’ expectations, needs, and desires3.

The COVID-19 pandemic raised concerns about loneliness, as it led to widespread physical isolation due to lockdown measures4. During this period, governments around the world put in place country-specific rules and unprecedented lockdown measures to slow down the spread of the virus. In Canada, provincial governments prohibited, to varying degrees, social gatherings, issued work-from-home mandates, and ordered the closure of public spaces like schools and restaurants5. Studies indicated a small but significant overall increase in loneliness during the pandemic, and suggested that this trend was not uniform across all groups, highlighting the importance of examining variations between individuals and risk factors in longitudinal studies6. While experiencing the pandemic concurrently, individuals may have exhibited varying baseline levels and patterns of change in their loneliness. For some, loneliness levels may have remained relatively stable, while others may have experienced a decrease or increase in their loneliness levels over time. Few studies have examined temporal and inter-individual variations in loneliness during the pandemic and how key loneliness risk factors, such as isolation and age, may have been associated with such variations. As we move beyond the pandemic, loneliness persists as a significant public health concern7. Understanding its dynamics during the acute phase of this crisis, considered a dramatic social change, is essential for informing future interventions and strategies to address loneliness 8.

Temporal and inter-individual variations of loneliness

Existing studies on loneliness rely mostly on cross-sectional approaches, but longitudinal research is crucial for understanding temporal variations during the COVID-19 pandemic9. Some longitudinal studies report lower levels of loneliness in summer months and higher levels in winter months but do not account for inter-individual differences in the experience of loneliness over time10. To our knowledge, only three studies derived loneliness trajectories during the pandemic, accounting for both temporal and inter-individual variations11,11,13. Despite important strengths, each is limited in some ways. One (n = 641) focused on older adults with chronic conditions in one metro area in the U.S., and thus does not provide information about younger people’s experiences of loneliness12. Another (n = 681), conducted with a French sample, derived four trajectories of loneliness over a year, but relied on a limited number of assessments obtained from a convenience sample over representing women and people with higher levels of education and did not include risk factors13. Finally, another study conducted in the UK derived four mainly stable loneliness trajectories using a substantial, non-random sample of adults (n = 38217) followed during a two-month lockdown period11. Several risk factors were associated with the higher loneliness trajectories, including being young, being a woman, having a low income, being unemployed, and having a mental health condition. Protective factors associated with lower loneliness trajectories included living with others, residing in rural areas, having more close friends, and reporting greater social support. Despite providing valuable insights, the generalization of the results is limited due to non-random sampling strategy and the assessment period restricted to two months. Considering that in Canada’s strictest provinces, isolation-related health measures were implemented intermittently for a period of two years, further research with representative samples and longer assessment periods are needed to explore how loneliness evolved over the course of the pandemic, as well as associated risk and protective factors.

Risk factors of loneliness

Socially isolated and younger individuals appear particularly vulnerable to the negative psychological consequences of lockdown measures, yet, these factors have not been studied sufficiently in relation to loneliness trajectories.

Social isolation

Loneliness is conceptually distinct from social isolation, which refers to the objective absence of social contacts14,15. In Peplau’s loneliness framework, social isolation is tied to actual social contacts2. Individual responses to social isolation vary : some individuals, like natural “loners,” do not feel particularly lonely when having limited contacts with others, while others feel lonely even when they have many social interactions and contacts16. Despite their conceptual differences, social isolation remains a major risk factor for loneliness17,18. The varying intensity of lockdowns and other social distancing measures during the pandemic has presented opportunities to deepen our understanding of the association between social isolation and trajectories of loneliness. Social isolation is a complex phenomenon that can be captured via a host of measurement strategies and indicators14,15. In this article, we look more specifically at social isolation impacted by pandemic-related measures with the help of three indicators: household composition, adherence to public health measures limiting in-person contacts, and online social contacts.

The first and most traditional indicator of social isolation refers to household composition. Living alone was already considered a marker of isolation related to loneliness before the pandemic15. Its impact on loneliness might have been amplified in pandemic context, when public gatherings outside one’s household were forbidden17. Research focusing on loneliness trajectories during the pandemic suggests that living alone was a risk factor for loneliness under pandemic conditions11,12. Further research is needed to determine whether these findings hold in representative samples of the general population and for trajectories of loneliness extending over longer periods.

One pandemic-specific indicator of social isolation is adherence to public health measures limiting in-person contacts (e.g., limitations of outdoor and indoor gathering). Throughout the crisis, in-person social contacts with friends and family were restricted by health measures, contingent on individual compliance. The limited research that has explored the relationship between loneliness and in-person contact indirectly suggests that those following distancing measures more strictly tended to experience increased loneliness17,18. However, the relationship between adherence to public health measures limiting in-person contacts and loneliness trajectories has not yet been examined.

Another pandemic-specific indicator for examining social isolation is through online social contacts. The pandemic accelerated the use of communication technologies as a primary means of interaction during lockdowns, of bridging social distance, and of providing social support17,19. Some authors have made recommendations in favor of using social media as a way to reach vulnerable and socially isolated young adults17. However, pre-pandemic studies found that adolescents with both limited in-person interactions and high social media use reported higher levels of loneliness18. Nowland et al. propose that Internet use can alleviate loneliness when it is employed to strengthen existing relationships20. Though no study has yet examined the relation between online social contacts and loneliness trajectories during the pandemic, we can expect that maintaining existing online relations could help alleviate loneliness during the pandemic20.

Young adults and loneliness

Age is considered one of the most critical determinants of loneliness21. Pre-pandemic studies have shown that young adults experience the highest levels of loneliness2,22,23. Adolescents and young adults are in a critical development stage where social interactions are necessary for key developmental tasks18. Recent research indicates that young adults were at a heightened risk of experiencing loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic10,17,24,25. The pandemic especially affected the youth through reduction of socializing spaces, closure of teaching institutions and online-schooling, and job losses in work sectors employing young adults26. Bu et al. reported that young adults aged 18–29 were more likely to experience higher loneliness trajectories during the pandemic. To confirm these findings, further investigation into the age-loneliness relationship over an extended pandemic period is essential11.

Current research

The current study is part of the project COVID-19 Canada: The end of the world as we know it? and unfolds in two main actions. We first aim to extend prior research on pandemic loneliness trajectories using a new representative Canadian sample and a one-year timeframe. Given the unique evolution of the pandemic and the lockdown measures specific to each government, studying changes in solitude in different countries is important17. Canada has been recognized for its effective response and strong public health measures27. We then aim to understand the significance of key risk factors for pandemic loneliness trajectories, which, to our knowledge, have not been thoroughly explored in existing studies. Our objectives are as follows:

Objective 1

Explore the inter-individual and temporal variations of loneliness in Canadians during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic by identifying trajectories of loneliness that will differ in terms of their initial level of loneliness (e.g., low, moderate, high) and their rate of change over time (e.g., stable, increasing, decreasing, unstable). Due to the exploratory nature of this objective, we do not develop any specific sub-hypothesis regarding the number and shapes of the trajectory groups28. Based on previous studies, we can expect a few stable trajectory groups of loneliness11,11,13.

Objective 2

Understand the association between social isolation and loneliness trajectories using one traditional (household composition) and two pandemic-specific indicators (adherence to public health measures and online social contacts) measured at a single time point. Regarding loneliness trajectory membership, we expect that (1) individuals who lived alone will be more likely to belong to high loneliness groups compared to those who lived with others; (2) individuals who followed isolation-related public health measures will be more likely to belong to high loneliness groups compared to those who did not and (3) individuals with fewer online contacts will be more likely to belong to high loneliness groups compared to those who had more online interactions.

Objective 3

Understand the association between young adulthood and loneliness trajectories. We expect that young adults will be more likely to belong to high trajectory groups of loneliness compared to older adults.

Objective 4

Explore the interactions between young adulthood and each social isolation indicator as risk factors of loneliness trajectories during the pandemic. To our knowledge, no studies have previously examined the interaction between age and isolation indicators for loneliness during the pandemic. Due to its exploratory nature, we do not provide any specific sub-hypothesis regarding this objective.

Results

Preliminary and descriptive analysis

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis, and correlations between continuous variables.

Objective 1: loneliness trajectory groups

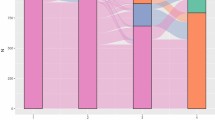

Table 2 shows the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) for model selection based on the number of trajectory groups as provided by PROC TRAJ. Model probability, included in the table, signifies the likelihood of each trajectory model being the best fit for the observed data. Our decision was to retain the five-class model, prioritizing meaningfulness of the retained trajectory groups. While a higher number of trajectories might yield a lower BIC, the six trajectories model failed to reveal a distinctive pattern within the data. Figure 1 depicts the elbow plot showing the BIC stabilizing at around five trajectories, further supporting the decision to retain the five-trajectory solution. This aligns with the theoretical adequacy criteria, as existing literature on loneliness trajectories mostly focuses on models with three to five groups11,11,13,29.

The shapes of the trajectories were determined using the BIC. Table 3 presents the parameters of the selected final model, which were determined using the BIC and level of significance. The BIC value for all models tested when determining the shapes of trajectories can be found in the supplementary materials (Table S1).

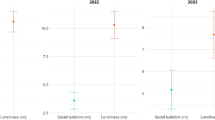

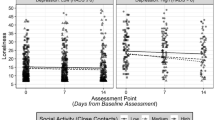

Figure 2 presents the five trajectory groups predicted by the model and the observed values. From bottom to top, the five trajectories were labelled and classified as follows: “Very low and stable,” “Low and unstable,” “Moderate and unstable,” “High and stable,” and “Very high and decreasing,” based on their starting level of loneliness and the stability of their evolution over time. Respectively, the first trajectory group had a very low loneliness level at the start of the study and remained stable over time (8.6% of the sample). The second trajectory group had low levels of loneliness at the start of the study (20.5% of the sample) which showed some variation over time (i.e., quadratic order). The modal trajectory group (38.5% of the sample) showed a moderate level of loneliness and a slight but significant change over time (i.e., cubic order), with decreasing loneliness in summer months and increasing loneliness in winter months and decreasing again in April 2021. The fourth trajectory group reported higher levels of loneliness which remained stable over time (26.7% of the sample). Finally, the fifth trajectory group reported very high loneliness levels that slightly decreased over time (5.7% of the sample). Figure 3 presents the five predicted trajectories with their confidence intervals.

Objective 2 and 3: linking trajectory groups with covariates

Covariates associated with trajectory group membership included household composition, adherence to public health measures limiting in-person contacts, online social contacts with friends and family, and age. Our final model included all the covariates in the multivariate multinomial regression, the results of which are reported in Table 4. Initial control variables included gender, education level, work status, student status, working from home, and being a parent. However, our final model included only gender, the only significant control variable in the preliminary bivariate multinomial regression analysis (see Tables S2-S13). The third trajectory (“moderate and unstable”) was used as the reference group when estimating the probabilities of membership for each trajectory group.

Objective 2: social isolation indicators as covariates

As expected, participants living alone were overrepresented in higher loneliness-level trajectories as compared to participants living with others. Compared to those in the modal group, participants living alone were more likely to belong to the “high and stable” trajectory (OR = 1.61, 95% CI = [1.06–2.45], p = .026) and to the “very high and decreasing” trajectory (OR = 3.24, 95% CI = [1.86–5.63], p < .001).

Contrary to our expectations, participants who adhered most to health measures were overrepresented in lower loneliness trajectories. Compared to the modal group, participants with low in-person contacts had higher odds of belonging to the “very low and stable” trajectory (OR = 3.77, 95% CI = [2.16–6.59], p < .001) and to the “low and unstable” one (OR = 1.93, 95% CI = [1.28–2.90], p = .002).

Also contrary to our expectations, participants with comparatively more online social contacts were more likely to belong to the “very high and decreasing” loneliness trajectory (OR = 2.43, 95% CI = [1.31–4.50], p = .005) and less likely to belong to the “very low and stable” loneliness trajectory (OR = 0.51, 95% CI = [0.28–0.91], p = .023), when compared to the same benchmark group.

Objective 3: young adulthood as a covariate

Even if some associations between young adulthood and trajectory membership were significant at p < .05 in bivariate analyses (see Supplementary Materials, Table S3), in our main multivariate model, none of the associations between young adulthood and loneliness trajectories reached the significance level of p < .05.

Control variable

Women were more likely than men to belong to the “high and stable” loneliness-level trajectory group as compared to the modal trajectory group (OR = 1.55, 95% CI = [1.05–2.30], p = .029).

Objective 4: interaction between young adulthood and isolation indicators

Table 5 shows descriptive statistics for each social isolation levels in each age group. No significant associations were found for interactions between young adulthood and each isolation indicator (Tables 6, 7 and 8). While no main effect was significant, exploratory post-hoc analyses to better understand the relation between isolation and loneliness can be found in supplementary materials (Tables S14-S16) as it may provide interesting insights for other researchers.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the inter-individual and temporal variations of loneliness during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in a representative Canadian sample, with social isolation and young adulthood as risk factors. Over the first year of the pandemic (April 2020–April 2021, 11 measurement times), five profiles of loneliness were identified, which differed in their initial levels and their variation over time (Objective 1). With regards to social isolation risk factors (Objective 2), traditional and pandemic-specific indicators of isolation were unexpectedly inversely associated with loneliness. By examining young adulthood as a risk factor (Objective 3) and interactions between young adulthood and isolation indicators (Objective 4), we found no significant associations in regards to loneliness trajectories.

Regarding Objective 1, our results highlight different temporal variations of loneliness during the pandemic. For the very high group, loneliness was slowly linearly decreasing. Loneliness was stable for the very low and high groups. As for the low and moderate groups, which represent the majority of our sample, such participants were unstable and appeared to follow a seasonal variation. For both unstable trajectories, their highest point was at the beginning of the pandemic (measurement time 2—April 2020). We then observed a general decrease, with the lowest point in summer (measurement times 6 and 8—June to August 2020). Laham et al. also reported loneliness trajectories showing a small decrease in loneliness during summer periods and a subsequent increase13. Our results do not allow us to discern whether loneliness fluctuated according to seasons or pandemic progression, as summer periods coincided with lower infection rates and loosening of health measures in Canada30. As health measures have now ceased, seasonality of loneliness would need to be further assessed, particularly among isolated individuals who are more vulnerable to winter-related distress10.

Our findings reveal that while certain groups exhibited some temporal variations, none of the trajectories cross over one another. The primary distinction lies in initial levels of loneliness revealing great inter-individual heterogeneity in Canadians’ feelings of loneliness, i.e., five distinct trajectories, contrasting with other studies of trajectories of loneliness typically identifying four trajectories11,11,13. This difference might reflect difference in sample size and composition, country, loneliness measurement, and analysis type. Our study was the only one to follow loneliness over 11 measurement times unevenly spread over 1 year, allowing a better assessment of variations than previous studies.

Our results also reveal that 26.7% and 5.7% of our sample reported high or very high loneliness. In a cross-sectional study performed by Statistics Canada in 2021, 13% of respondents reported always or often feeling lonely31. Similarly, Bu et al. reported that their highest trajectory (out of four) in the UK sample was very high and increasing and represented 14% of their sample11. While it is difficult to compare with other studies using different loneliness measurements or number of trajectories, our results reveal high loneliness levels in specific groups during the pandemic’s first year, representing a particularly significant portion of the Canadian population. The high and stable trajectory indicate that more than 30% of the Canadian population could have experienced enduring high levels of loneliness, unaffected by seasons or variations in public health measures32. This potentially represent a group vulnerable to chronic loneliness and highlights the need to examine risk factors providing insights into the composition of these groups.

Regarding Objective 2, our findings indicate that social isolation indicators have contrasting associations with loneliness, shedding light on the complex and seemingly paradoxical relationship between isolation and loneliness. When considering household composition, a traditional indicator of social isolation, solo living was associated with a higher likelihood of belonging to the highest loneliness trajectories (high stable and very high decreasing), consistent with previous studies and our initial hypothesis11. However, when considering pandemic-specific indicators, i.e., compliance with health measures and online social contact, reversed associations were unexpectedly observed.

Those complying with health measures had a comparatively higher probability of belonging to the two lowest loneliness trajectories (very low stable and low unstable). One study on adherence to public health measures suggests that lower engagement in COVID-19 preventive behaviors can be followed by higher loneliness33. Although adherence to public health measures was assessed prior to loneliness in our study, it is possible that adherence and loneliness are mutually influencing, which may explain why our findings diverged from what we initially anticipated. Shared experiences of isolation may also have strengthened social cohesion and the feeling of togetherness34. Some studies suggest a potential increase in resilience, social support, and sense of belonging to a community during the pandemic, limiting the rise in loneliness34. This was exemplified by nationwide events of residents applauding from windows in Italy and Spain35. Our data lack a direct measure of social support to test this hypothesis, which would need to be validated in future longitudinal studies.

Regarding online social contacts, we initially proposed that an absence of online social contacts could isolate individuals, and thus increase feelings of loneliness. Our results show the opposite: participants having more online contacts with friends and family at the beginning of the pandemic had more chances belonging to the highest loneliness trajectory (very high and decreasing) and fewer chances of belonging to the lowest loneliness trajectory (very low and stable). Although communication technologies offer alternative ways to connect with others, the benefits of their use are mixed. Technologies sometimes represent the only means of contact and of exchanging support17,19. During the pandemic, turning to technologies was sometimes recommended to maintain social ties, bridge social distance as well as to convey and receive social support during periods of social isolation17. One research suggests that online social contacts can be an adaptive strategy, especially for lonely individuals during the pandemic, offering a temporary means to stay in touch and receive support36. However, in the long term, online contacts cannot be a definitive solution to alleviate loneliness during an extended period of isolation and their extensive use could even be associated with increased loneliness36. Boursier et al. mention that online social contacts can have certain benefits (well-being, sense of belonging), but especially when combined with in-person social contacts36. This should be considered when designing solutions for alleviating loneliness during periods of social distancing as well as in the post-COVID era, as online activities continue to replace in-person ones for the sake of convenience. The association between online social contacts and loneliness still needs to be studied, especially regarding the type of technology use and the intention behind its use20.

As for Objective 3, contrary to our expectations, our study did not reveal significant differences between young and older adults regarding loneliness levels. This could be explained our use of a self-reported single-item loneliness measure which fails to capture different dimensions of loneliness. Previous studies distinguish emotional from social loneliness, which respectively pertains to close and intimate bonds and broader social networks37. Young adults tend to prioritize quantity of social contacts over quality, as evidenced by their efforts to expand their friendship networks and spend more time with unfamiliar individuals23,38. They are more prone to social forms of loneliness when their needs are not met23. In contrast, midlife and older adults may experience emotional loneliness when their needs for social contacts are not met qualitatively23. This idea is consistent with the socioemotional selectivity theory, which posits that as we age, we prioritize emotionally meaningful relationships over broader social networks39. Other longitudinal studies using multi-item scales of loneliness indicate that young adults could be more likely to report loneliness during the pandemic11. We did not examine the difference in loneliness dimensions in relation to age, which could explain our non-significant findings. Those results do not imply an absence of loneliness for young adults, as results show high levels of loneliness across all data set, including youth. Further research should employ a more comprehensive measure of loneliness that accounts for its various dimensions and their association with age.

Regarding Objective 4, our exploratory analysis did not reveal a significant interaction with young adulthood and compliance with health measures in relation to membership in loneliness trajectories. Similarly to Objective 2, the results could be explained by the absence of various loneliness dimensions. Larger sample size in interactions subgroups could also yield different results. The relationship of isolation indicators and loneliness should be further explored and interactions with other variables like gender could be examined.

This study was the first to explore the temporal and inter-individual variations of loneliness during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada by including different isolation indicators and young adulthood as risk factors. Its strengths include its longitudinal design, the representativeness of the Canadian sample, the scope of the period under study, and the number of measurement times, increasing the reliability of the results. It is still important to interpret the results considering several limitations. Even if single-item measures of loneliness have been validated and used in the literature, they remain limited13,40,41. Future studies should use validated loneliness scales that also account for loneliness subtypes42. Second, the COVID-19 Canada: The end of the world as we know it? project was put in place as a response to the pandemic and does not provide pre-pandemic data. Our analysis remains correlational, and we cannot verify if our results are different than they would have been before the pandemic. The variability of time-varying covariates, like adherence to public health measures and online social contacts, was not included. These behaviors could have been unstable over time and their association with loneliness could have changed throughout the course of the pandemic. Future studies should account for regional variations in pandemic measures as well as explore underrepresented subgroups, such as genderqueer individuals, to better understand how loneliness varies across diverse populations during crises like the COVID-19 pandemic.

As loneliness was already an important public health issue, the pandemic has increased concerns about loneliness levels in the population. Our results confirm that loneliness is a heterogeneous experience and indicate that a significant portion of the population reported high levels of loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Women were more likely to report high levels of loneliness while no significant interaction were found between young adults and isolation factors. Unexpectedly, traditional and pandemic-specific indicators of isolation were inversely associated with loneliness: individuals living alone—a traditional indicator of isolation—had greater chances of reporting high levels of loneliness. In contrast, those adhering to health measures were more likely to belong to low loneliness trajectories and individuals having more online social interactions were more likely to report high loneliness. As we move beyond the pandemic and with loneliness still being a concern, this study underscores the need to reassess and diversify indicators when measurement approaches of social isolation and loneliness. The findings highlight that loneliness is a complex experience, impacting many and deserving further attention.

Methods

Participants and data source

Participants were drawn from a large-scale longitudinal project: COVID-19 Canada: The end of the world as we know it?43. The survey consisted of twelve measurement times (MT) spanning from April 2020 to April 2022, at irregular intervals. At MT 1, the sample included 3617 Canadian adults (Mage = 47.63; 50.5% women) recruited by a survey firm and was representative of the Canadian population in terms of gender, age, and region of residence43. Owing to attrition the average participation rate was 58% for measurement times two through eleven. Table 9 provides information about each assessment period at each MT of the survey. At each wave of the study, participants gave their informed consent to take part in this study and completed all the questionnaires online in French or in English.

Procedure

The survey was based on a longitudinal rolling design. For the first MT, participants were randomly assigned to one of 14 participant pools. Each day of data collection, the survey was opened for a new participant pool. Participants had between 7 and 14 days to complete each survey while it was opened for their participant pool (for more information, see Table 9). This allowed to record the effects of the pandemic in real time without overburdening the participants. Completing each questionnaire took between 15 and 20 min. Participants earned approximately 2.50 Canadian dollars per completed questionnaire, redeemable at partner companies43. All the procedures in the longitudinal project were reviewed and approved by the University of Montreal’s research ethic committee in education and psychology (CEREP) and was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants who completed the first MT were invited to complete all subsequent ones, even if they missed one or more MTs. As a result, the number of MTs to which participants responded varied. To reduce the survey’s length and cost while including as many items as possible, the COVID-19 Canada project used a planned missingness approach (for an overview, see Wu and Jia 2021). In that project, participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups. Each item under planned missingness was randomly presented to two groups out of three. In other words, items under planned missingness have 33% missing data for each MT. It is important to note that as missing data coming from planned missingness is random in nature it does not introduce a bias in the data collection44. Among the variables used in the current study, only loneliness was under the planned missingness protocol from MT 7 to MT 11.

Exclusion criteria

First, within each MT, we excluded participants who completed a questionnaire too quickly (i.e., less than four minutes), as recommended by the survey firm. From MT 1 to MT 11, the number of participants who completed each survey under 4 minutes varied between 2 and 29 with an average of 11 (SD = 8). No time limit was set excluding slow completions: participants could complete the questionnaire over multiple days and in several sittings. Then, from the second MT onward, we added two attention check items (“This is a test item. Please select ‘2’ for this item.”). For each MT, participants who failed the two test items were removed from that MT. From MT 2 to MT 11, between 52 and 88 participants failed both test items with an average of 71 (SD = 14). Third, we excluded participants who did not answer at least three MTs for the dependent variable (i.e., “loneliness,” starting from MTs 2 to 11), as this is the minimum number of MTs required for modelling linear trajectories of change. Fourth, we excluded participants identifying themselves as “other” in terms of gender, as they represented a negligible proportion of the sample (n = 2, 0.1%). Fifth, we excluded participants who did not answer questions about the independent variables (i.e., age, online social contacts) at MT 1. Some variables had missing data related to planned missingness at MT 1. As planned missingness is assigned to random participants, our study only concerns those who answered these questions. These five exclusion criteria resulted in a final sample consisting of 1761 adults at measurement time 1 (Mage =49.5; SDage = 16.7; 50.6% women).

Sample representativeness

Although the sample’s representativeness was established using the first MT of the survey and trajectory analysis using FIML, missing data due to attrition may impact the results as well as the sample’s representativeness43. In order to increase our sample’s representativeness, a weighting procedure was applied45 to adjust for identifiable socio-demographic deviations, based on available data from Statistics Canada. The weighting procedure was conducted under the “raking” function from the Icarus package on R46. It was designed to select the best combination of calibration variables (among gender, province of residence, number of people in the household, number of minors in the household, Canadian born, Aboriginal origin, mother tongue, and education) that minimized the average estimation error on a range of 13 external benchmark measurements. In short, the weighting procedure tried to find the balance between reducing the bias due to the lack of representativeness of the sample and artificially increasing standard errors. The maximum range of the weights was fixed at 2.5. The weights ranged between 0.5231 and 3.0231 with a mean of 1. The weighting process reduced bias by 8.67%, according to the selected benchmark variables. All of the subsequent analysis were performed with the weights.

Measures

Socio-demographic information was collected during MT 1 (Table 10) and has been recorded in the present study. They include age (open question) and gender (coded as 0 = woman, 1 = man, 2 = others), level of education (recoded as 0 = no university education and 1 = university education), immigration status (indicated by country of birth and recoded as 0 = Canada, 1 = Other countries), having children (recoded as 0 = no or 1 = yes), student status (recoded as 0 = not being a student and 1 = being a student), working status (recoded as 0 = unemployed and 1 = employed) and working from home (recoded as the number of hours and minutes per day and dichotomized at the median).

Self-reported loneliness was assessed at each data MT with a single item question (“In the past week, due to the COVID-19 crisis, I have often felt lonely.”) providing information about on their subjective feeling of loneliness. Participants rated on a 10-point scale (1 = Never, 10 = Always). In the present trajectory analysis, loneliness data was taken from MTs 2 to 11 to make sure the risk factor variables were pre-existent of the trajectories. The inclusion of risk factor variables at time 1 was aimed at understanding their association with initial loneliness levels and their potential influence on trajectory patterns. This approach explores how preexistent factors predict subsequent loneliness experiences and trajectories over time.

Based on other validated scales, like UCLA Loneliness scale and Three-Item loneliness scale, we considered scoring 7 or higher out of 10 to be high loneliness and 4 or lower out of 10 to be low loneliness. This question was part of a larger question assessing other positive and negative feelings associated with quarantine inspired by those found in previous studies47. Considering constraints posed by limited resources and time, we opted to employ a single-item measure to assess loneliness in this study. This approach aligns with findings from prior research which validated the single-item measure of loneliness40. However, it’s important to acknowledge that this measure comes with the drawback of reduced comprehensiveness and that we cannot fully capture the complexity of loneliness using this approach.

The young adult group was created with the age variable (0 = adults 30–99 years old; 1 = young adults 18–29 years old), in accordance with the young adulthood range established by prior research17.

Household composition was assessed at MT 1 with a single item “Counting yourself, how many people currently live with you?” The variable was later dichotomized (0 = Living with one or more other person; 1 = Living alone). Adherence to public health measures limiting in-person contacts was assessed at MT 1 by averaging two items: “Currently I stay at home as much as I can” - which was reverse coded - and “Currently I invite people over for dinner or coffee.” Participants rated on a 10-point scale (1 = Never, 10 = Always). The isolation variable was later dichotomized according to the median (0 = Low isolation; 1 = High isolation). These items reflected public health recommendations48. Online social contact was assessed at MT 1 with a single item: “Indicate the number of hours per day you talk to friends and family using online platforms.” Participants indicated how many hours and minutes per day they spoke to significant others. We transformed the time reported to total hours. The ceiling value was set at 12 h, so that all answers which took longer than 12 h to complete were set as having taken 12 h. The online social contacts variable was inverted to assess isolation as a risk factor and dichotomized according to the median (0 = High online social contacts; 1 = Low online social contacts).

For the purpose of this analysis, these risk factors were measured at a single time point (MT 1), and the variability of time-varying covariates throughout the study period was not included in the analysis.

Descriptive analyses of dichotomized risk factors are available in supplementary materials (Table S17). While recognizing the loss of some information, we chose to dichotomize the risk factors due to their non-normal distribution. Dichotomization additionally allowed exploration of interaction analysis. Median rather than quartile dichotomization was done to achieve larger sample size.

Statistical analysis

Data preparation including weighting analyses was performed on RStudio. Data cleaning and other manipulations were conducted on IBM SPSS Statistics 26. SAS 9.4 was used for all subsequent data analysis. Our analysis was inspired by previous studies who examined prejudice and self-compassion trajectories using the same COVID-19 Canada: The end of the world as we know it? data49,50.

Objective 1

Our statistical analysis involved examining loneliness trajectories through semiparametric group-based trajectory modelling as developed by Nagin (1999) using the PROC TRAJ procedure in SAS 9.4 software51,52. This analysis works by grouping distinct groups of individuals within a population that reported similar patterns of change over time, enabling exploration of both intra-individual (e.g., over time) and inter-individual (e.g., between identified subgroups) changes. The grouping of individuals is based on their trajectory shapes, which are characterized by their loneliness value across different time points. This statistical analysis also provides the advantage of allowing for unevenly spaced time intervals. Trajectory groups were modelled with the censored-normal distribution (CNORM), as the loneliness variable was continuous and followed a relatively normal distribution52. The first step of trajectory analysis involves determining the optimal number of trajectory groups. This was done by considering three criteria: (1) the substantive meaning (meaningfulness) of the trajectory groups (i.e., the trajectories make sense and each additional profile is qualitatively (and not only quantitatively) different from the solution with one fewer profile), (2) the theoretical conformity (i.e., the trajectories are sound based on theoretical expectations), and (3) the statistical adequacy (i.e., statistical indicators support the retained solution)53,53,54,56. More specifically we considered several statistical indicators, including the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and model probability57,58. The decision is often based on the BIC where the value closest to zero indicates a better fit of the model with the data52,59. However, as the BIC often tends to continue getting closer to 0 as more trajectory groups are added, some recommend relying on an “elbow plot” to illustrate the gains for each additional profile60. In an elbow plot, the point (or number of trajectory groups) after which the slope flattens suggest the optimal number of groups. After identifying the optimal number of trajectory groups, the second step involves determining the optimal polynomial function of each trajectory (e.g., constant, linear, quadratic, cubic) according to the BIC52,59. To determine the polynomial function of each trajectory, an iteration is performed sequentially on the trajectory while maintaining other trajectories constant. For example, the shape of the first trajectory is fixed at 1 (order 1, linear trend) while the shape of other trajectories remains fixed at zero. The BIC is noted after each iteration as well as the p-value of the higher order parameter (i.e., constant, linear or quadratic) descripting the shape of the trajectory. That process is repeated for a quadratic trend (order 2) and cubic trend (order 3). The retained shape of a trajectory is the one with the BIC closest to zero which has a significant higher order parameter (p < .05; see Table S1 for parameters value).

Objectives 2 and 3

Preliminary analyses included chi-square analyses using SPSS and bivariate multinomial logistic regression using POC TRAJ. There are available in supplementary materials (Tables S2–S13). Main analyses consisted in conducting multivariate multinomial regression using the RISK function in PROC TRAJ, to assess the covariates of trajectory membership. This function estimates the probability of membership in each trajectory group, according to a reference trajectory, based on covariate variables. We selected the modal trajectory as our reference—which also represents the average loneliness experience—over choosing the lowest or highest trajectory due to their limited representation. Our core aim was to uncover how risk factors are associated with deviations from the common loneliness trajectory group.

Objective 4

Finally, we examined the association between loneliness trajectories and the interaction effects involving isolation indicators and young adult status. Each isolation indicator was analyzed separately. We introduced an interaction variable along with the two original risk factor variables in a logistic multinomial regression model using the RISK function of PROC TRAJ.

Data availability

The scripts and databases are available on OSF (https://osf.io/pg3w9/?view_only=91ae6093a4284bf7a1853ec54ec10bab).

References

Cacioppo, J. T. & Patrick, W. Loneliness: Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (2009).

Peplau, L. A. & Perlman, D. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy. In Wiley Series on Personality Processes (Wiley, 1982).

Ph, L. C., Hawkley, D., Ph., J. T. & Cacioppo, D. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 (2010).

Holt-Lunstad, J. & Perissinotto, C. M. Isolation in the time of covid: what is the true cost, and how will we know? Am. J. Health Promot. 36(2), 380–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171211064223 (2022).

Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Canadian COVID-19 Intervention Timeline. (2023). https://www.cihi.ca/en/canadian-covid-19-intervention-timeline

Ernst, M. et al. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. 77(5), 660–677. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001005 (2022).

Office of the U.S. Surgeon General. Our Epidemic Loneliness Isolation (2023).

de la Sablonnière R. Toward a psychology of social change: a typology of social change. Front. Psychol. 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00397 (2017).

Pellerin, N., Raufaste, É. & Corman, M. Psychological resources and flexibility predict resilient mental health trajectories during the French covid-19 lockdown. Nat. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14572-5 (2022).

Hu, Y. & Gutman, L. The trajectory of loneliness in UK young adults during the summer to winter months of COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 303, 114064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114064 (2021).

Bu, F., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Loneliness during a strict lockdown: trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 265, 113521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521 (2020).

Kotwal, A. A. et al. Persistent loneliness due to COVID-19 over 18 months of the pandemic: a prospective cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.18010 (2022).

Laham, S. et al. Impact of longitudinal social support and loneliness trajectories on mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in France. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 18(23), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312677 (2021).

Holt-Lunstad, J. & Steptoe, A. Social isolation: an underappreciated determinant of physical health. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 43, 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.07.012 (2022).

Newall, N. E. G. & Menec, V. H. A comparison of different definitions of social isolation using Canadian longitudinal study on aging (CLSA) data. Ageing Soc. 40(12), 2671–2694. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19000801 (2020).

Donovan, N. J. & Blazer, D. Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: review and commentary of a National academies Report. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28(12), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.08.005 (2020).

Bu, F., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public. Health 186, 31–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.036 (2020).

Twenge, J. M., Spitzberg, B. H. & Campbell, W. K. Less in-person social interaction with peers among U.S. adolescents in the 21st century and links to loneliness. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 36(6), 1892–1913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519836170 (2019).

Shah, S. G. S., Nogueras, D., van Woerden, H. C. & Kiparoglou, V. The COVID-19 pandemic: a pandemic of lockdown loneliness and the role of digital technology. J. Med. Internet Res. 22(11), e22287. https://doi.org/10.2196/22287 (2020).

Nowland, R., Necka, E. A. & Cacioppo, J. T. Loneliness and social internet use: pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13(1), 70–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617713052 (2018).

Qualter, P. et al. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10(2), 250–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615568999 (2015).

Shovestul, B., Jiayin, H., Laura, G. & David, D. F. Risk factors for loneliness: the high relative importance of age versus other factors. PLoS ONE 15 (2), 87. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229087 (2020).

Victor, C. R. & Yang, K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. J. Psychol. 146, 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.613875 (2012).

Liu, C. H. et al. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res. 290, 113172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172 (2020).

Losada-Baltar, A. et al. ‘We are staying at home.’ Association of self-perceptions of aging, personal and family resources, and loneliness with psychological distress during the lock-down period of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 76, e10–e16. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa048 (2020).

Gagné, T., Nandi, A. & Schoon, I. Time trend analysis of social inequalities in psychological distress among young adults before and during the pandemic: evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study COVID-19 waves. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 76(5), 421–427. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2021-217266 (2022).

Razak, F., Shin, S., Naylor, C. D. & Slutsky, A. S. Canada’s response to the initial 2 years of the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison with peer countries. CMAJ 194, E870–E877. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.220316 (2022).

Nylund-Gibson, K. & Choi, A. Y. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl. Issues Psychol. Sci. 4(4), 440–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000176 (2018).

van Dulmen, M. H. M. & Goossens, L. Loneliness trajectories. J. Adolesc. 36(6), 1247–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.001 (2013).

Radio-Canada. Où en est la pandémie de COVID-19?|Radio-Canada. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/info/2020/09/covid-19-pandemie-cas-deces-propagation-vague-maladie-coronavirus/ (2023).

S. C. Government of Canada. The Daily—Canadian Social Survey: Loneliness in Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/211124/dq211124e-eng.htm (2023).

Martín-María, N. et al. Effects of transient and chronic loneliness on major depression in older adults: a longitudinal study. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 36(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5397 (2021).

Stickley, A., Matsubayashi, T. & Ueda, M. Loneliness and COVID-19 preventive behaviours among Japanese adults. J. Public. Health 43(1), 53–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa151 (2021).

Luchetti, M. et al. The trajectory of loneliness in response to COVID-19. Am. Psychol. 75, 897–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000690 (2020).

BBC News. Coronavirus: Spain and Italy applaud health workers. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-europe-51895386 (2023).

Boursier, V., Gioia, F., Musetti, A. & Schimmenti, A. Facing loneliness and anxiety during the COVID-19 isolation: the role of excessive social media use in a sample of Italian adults. Front. Psychiatry 11, 222. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586222 (2020).

Weiss, R. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation (MIT Press, 1973).

Fardghassemi, S. & Joffe, H. The causes of loneliness: the perspective of young adults in London’s most deprived areas. PLoS ONE 17(4), e0264638. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264638 (2022).

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M. & Charles, S. T. Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 54(3), 165–181 (1999).

Mund, M. et al. Would the real loneliness please stand up? The validity of loneliness scores and the reliability of single-item scores. Assessment 30(4), 1226–1248. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911221077227 (2023).

Schmidt, N. & Sermat, V. Measuring loneliness in different relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 44(5), 1038. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.5.1038 (1984).

Hyland, P. et al. Quality not quantity: loneliness subtypes, psychological trauma, and mental health in the US adult population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 54(9), 1089–1099. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1597-8 (2019).

de la Sablonnière, R. et al. COVID-19 Canada: The End of the World as We Know It? (Technical Report No. 1): Presenting the COVID-19 Survey (Université de Montréal, 2020).

Caron-Diotte, M. et al. COVID-19 Canada: The End of the World as We Know It? (Technical Report No. 2). Handling Planned and Unplanned Missing Data (Université de Montréal, 2021).

Mercer, A. et al. For Weighting Online Opt-In Samples, what Matters Most? https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/2018/01/26/for-weighting-online-opt-in-samples-what-matters-most/ (Pew Research Center, 2028).

Rebecq, A. icarus: Calibrates and Reweights Units in Samples. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/icarus/index.html (2024).

Reynolds, D. L. et al. Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiol. Infect. 136(7), 997–1007. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268807009156 (2008).

Public Health Agency of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.html

Ferrante, V. M. et al. Covid-19, economic threat and identity status: Stability and change in prejudice against Chinese people within the Canadian population. Front. Psychol. 13, 352. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.901352 (2022).

Kil, H. et al. Initial risk factors, self-compassion trajectories, and well-being outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic: a person-centered approach. Front. Psychol. 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1016397 (2023).

Jones, B. L. & Nagin, D. S. Advances in group-based trajectory modeling and an SAS procedure for estimating them. Sociol. Methods Res. 35(4), 542–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124106292364 (2007).

Nagin, D. S. Analyzing developmental trajectories: a semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychol. Methods 4(2), 139–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.2.139 (1999).

Bauer, D. J. & Curran, P. J. Distributional assumptions of growth mixture models: implications for overextraction of latent trajectory classes. Psychol. Methods 8(3), 338–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.338 (2003).

Frankfurt, S., Frazier, P., Syed, M. & Jung, K. R. Using group-based trajectory and growth mixture modeling to identify classes of change trajectories. Couns. Psychol. 44(5), 622–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016658097 (2016).

Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Trautwein, U. & Morin, A. J. S. Classical latent profile analysis of academic self-concept dimensions: synergy of person- and variable-centered approaches to theoretical models of self-concept. Struct. Equ Model. Multidiscip. J. 16 (2), 191–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510902751010 (2009).

Muthén, B. Statistical and substantive checking in growth mixture modeling: comment on Bauer and Curran Psychol. Methods 8, 369–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.8.3.369 (2003).

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T. & Muthén, B. O. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct. Equ Model. Multidiscip J. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396 (2007).

Nagin, D. S. & Odgers, C. L. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 6(1), 109–138. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413 (2010).

D’unger, A. V., Land, K. C., McCall, P. L. & Nagin, D. S. How many latent classes of delinquent/criminal careers? Results from mixed Poisson regression analyses. Am. J. Sociol. 103(6), 1593–1630. https://doi.org/10.1086/231402 (1998).

Petras, H. & Masyn, K. General Growth Mixture Analysis with Antecedents and Consequences of Change 69–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-77650-7_5 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Élizabeth Olivier who revised this article. Finally, we would like to thank to all students in the lab and collaborators who were involved in the development or improvement of the study.

Funding

This project was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) of Canada. The authors have no commercial or financial interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FJ contributed to the research idea, statistical analysis, and preparation of the manuscript, under the theoretical and methodological supervision of VD, RdlS, and MP-D. ÉL, AD, MP-D, J-ML, DS, and RdlS were responsible for the project programming and implementation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jarry, F., Dorfman, A., Pelletier-Dumas, M. et al. Understanding the interplay between social isolation, age, and loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci Rep 15, 239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81519-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81519-3