Abstract

This study investigates the impact of hemoglobin A1c on platelet reactivity and cardiovascular outcomes in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation. HbA1c levels were categorized into 3 groups: < 6.5%, 6.5–8.5%, and > 8.5%. ROC (resistance to clopidogrel) and ROA (resistance to aspirin) were calculated. The primary endpoint was a composite of MACE, including all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, and ischemia-driven revascularization. The secondary endpoints comprised individual MACE components. The incidence of ROC was 9.3% (151 of 1621), whereas that of ROA was 16.5% (268 of 1621). The ROC for each of the 3 groups significantly increased with increasing HbA1c levels [4.3% vs. 7.1% vs. 10.1%, p = 0.006]; however, the ROA did not [16.4% vs. 17.7% vs. 14.3%, P = 0.694]. HbA1c > 8.5 was significantly associated with ROC (3.356 [1.231, 9.234], p = 0.009). Compared with the HbA1c < 6.5 subgroup, the HbA1c˃8.5 subgroup was significantly associated with MACE (3.142 [2.346, 4.206], < 0.001), nonfatal MI (2.297 [1.275, 4.137], P = 0.006) and ischemia-driven revascularization (3.845 [2.082, 7.101], p < 0.001), but not all-cause mortality (2.371 [0.551, 10.190], 0.246) at the 36-month follow-up. HbA1c levels were positively correlated with ROC, but the adverse cardiovascular events were driven by elevated HbA1c, constituting an argument to intensify glycemic control in subjects with diabetes after intracoronary stent placement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Key aspects associated with diabetes mellitus, such as hyperglycemia, inflammation, and oxidative stress, increase platelet reactivity1. Currently, high residual platelet reactivity in patients after clopidogrel treatment has been confirmed to be an independent predictor of adverse cardiovascular events following coronary stent implantation2,3,4,5,6,7,8. In addition, numerous studies9,10,11 have also verified that elevated glycated hemoglobin levels indicate an adverse cardiovascular prognosis. These findings may imply that high residual platelet reactivity is a driving factor of adverse cardiovascular events after intracoronary stenting in patients with hyperglycemia and that intensified antiplatelet therapy is required in patients with hyperglycemia after PCI with a drug-eluting stent. Nonetheless, the associations between platelet reactivity, glycemic control status and outcomes in patients after PCI with a drug-eluting stent remain unclear. Additionally, a few studies12,13 have failed to demonstrate that glycated hemoglobin levels are independently associated with platelet activity or that lower platelet reactivity after intensive glycemic control in patients with poorly controlled glycemia, meaning that glycemic control has no impact on platelet reactivity14. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether glycated hemoglobin levels were independently associated with high residual platelet activity in a large-scale Chinese population and whether the correlation between glycated hemoglobin and clinical prognosis was mediated by high residual platelet activity, thereby establishing an argument for intensive antiplatelet therapy in patients with poor glycemic control.

Methods

Study population

A total of 1621 patients who underwent intracoronary drug-eluting stent implantation at Shanghai General Hospital and Jiading Branch of Shanghai General Hospital from January 2016 to January 2021 and who simultaneously underwent HbA1c and TEG (thromboelastographic) testing were consecutively enrolled. All patients signed informed consent forms before the procedure. Patients were divided into three groups based on their HbA1c levels (< 6.5, 6.5 ≤ HbA1c ≤ 8.5, and HbA1c > 8.5), and relevant clinical data and biochemical parameters were collected. The grouping of the HbA1c cut points were predetermined based on findings from previous cohorts9,15. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age < 18 years; (2) severe hepatic dysfunction (transaminase greater than 5 times the upper limit of normal); (3) severe renal failure (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 30 ml/min*1.73 m2 or renal replacement therapy); (4) abnormal coagulation function (international normalized ratio, INR ≥ 1.5); (5) recent (< 6 months) history of severe active bleeding or major surgery; (6) allergy or contraindications to aspirin or clopidogrel; and (7) platelet count < 60*109/L or > 500 × 109/L.

Data extraction

The following participant data were collected from the hospital’s electronic medical records: demographic information (age, sex), smoking status, vital signs (heart rate, blood pressure), body mass index, medical history (prior MI, prior PCI, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia), medication (aspirin, clopidogrel, beta blocker, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor [ACEI], angiotensin receptor blocker [ARB]), laboratory parameters (platelet, troponin I [TNI], B-type natriuretic peptide [BNP], high-sensitivity C-reactive protein [hs-CRP], low-density lipoprotein cholesterol [LDL-C], creatinine, albumin (g/L), hemoglobin(g/dl), left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF], coronary angiography results (left main [LM] lesion, left anterior descending [LAD] lesion, stents > 2, calcified coronary lesion), acute coronary syndrome.

Methods of medication for antiplatelet drugs

Aspirin was administered either as (1) an oral chewed dose of 300 mg at least 6 h before PCI or (2) a dose of 100 mg/day for at least 5 days before PCI. Clopidogrel was given either as (2) at an oral dose of 600 mg at least 6 h before the procedure, (2) at a dose of 300 mg at least 12 h before the procedure, or (3) at a dose of 75 mg/day for at least 5 days before PCI. Platelet activity is tested after successful stenting and after an adequate period (at least 12 h after procedure) to ensure sufficient antiplatelet effects using TEG. If tirofiban was used intraoperatively, a 24-h washout period was required before platelet reactivity estimation. After successful PCI, patients were treated with aspirin (100 mg/day) indefinitely, and clopidogrel (75 mg/day) was administered for at least 1 year.

Definition of ROC, ROA, and outcome

ROC (resistance to clopidogrel, ROC) and ROA (resistance to aspirin) were defined as the ADP (adenosine diphosphate.) inhibition rate of less than 30% and an AA (Arachidonic Acid.) inhibition rate of less than 50% by TEG, respectively16,17. The primary outcome was a composite outcome, main adverse cardiovascular event (MACE), which included all-cause mortality, nonfatal MI, and ischemia-driven revascularization. The secondary endpoints were individual components of MACE. The events adjudication committee consisted of veteran clinicians who were unaware of the clinical treatment regimens adjudicated for the primary and secondary outcomes.

Follow-up

After successful PCI, all patients were routinely followed up at 3, 6, and 12 months until 36 months post-procedure by telephone with patients or their family members. If patients experienced more than one adverse event during the 36-month follow-up period, only the first occurrence was counted for this study.

Statistical analysis

All participants were categorized into three groups based on their glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels. For normally distributed parametric data, variables are described as the mean ± standard deviation (sd); otherwise, they are described as the median (interquartile range). Intergroup differences were assessed by the Kruskal‒Wallis test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (%), and differences between groups were tested by the Chi-square test.

Kaplan‒Meier curves were used to compare the 36-month incidence of MACE, all-cause death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and ischemia-driven revascularization between different HbA1c groups by the log-rank test. Cox regression analysis was performed to further examine the relationship between HbA1c levels and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, with the HbA1c < 6.5 group serving as the reference group. Regression analysis results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Covariates were included in the regression analysis based on statistical evidence (stepwise method with exclusion at P > 0.05) and clinical judgment. Additionally, based on the Cox regression analysis model, we plotted a restricted cubic spline to investigate the relationship between HbA1c levels as a continuous variable and MACE with three knots. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to assess the predictive value of HbA1c levels for MACE, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated.

All analyses were performed with SPSS version 23, and plots were constructed in R version 4.3.3 using the ggplot package 2. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests, which were two-tailed.

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics

A total of 1621 patients who underwent PCI treatment and hemoglobin A1c testing were included in this study. These patients were divided into three groups based on their hemoglobin A1c levels. ; HbA1c < 6.5 (n = 1103), 6.5 ≤ HbA1c ≤ 8.5 (n = 341), HbA1c > 8.5, n = 117.

Compared to patients with lower hemoglobin A1c levels, a greater proportion of patients with higher hemoglobin A1c levels were female, had a greater heart rate, and had a greater incidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) and diabetes. Moreover, they received more ACEI and ARB therapy. In terms of laboratory parameters, participants with high hemoglobin A1c levels had a higher TNI, BNP, and hsCRP, whereas the level of hemoglobin was lower. Patients with higher hemoglobin A1c levels were more likely to be diagnosed with acute coronary syndrome and had a greater risk of left main vessel and calcified lesions and a greater probability of implantation of stents > = 2 (Table 1).

Platelet reactivity test and association between hemoglobin A1c levels and ROC

The median inhibition rates of AA for each group were similar (88.8 [60.2, 98.6], 88.1 [61.2, 97.9], and 83.9 [61.1, 98] for HbA1c < 6.5, 6.5 ≤ and ≤ 8.5, and > 8.5, respectively; P = 0.83), whereas the median inhibition rate of ADP increased significantly with increasing HbA1c levels (90.8 [57.6, 98.6], 80 [52.4, 98.2], 73 [42.4, 96.1], P = 0.03).

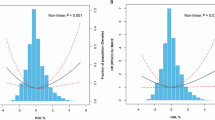

A total of 9.3% patient (151 of 1621) had ROC defined by inhibition rate of ADP < 30%, and the incidence of ROC for each groups was dramatically different (4.3% [17/396], 7.1% [8/130], 10.1% [4/56], for HbA1c < 6.5, 6.5 ≤ and ≤ 8.5, and > 8.5, respectively; P = 0.006, Fig. 1a), whereas more than 16.5% patients (268 of 1621) had ROA defined by inhibition rate of AA < 50%,and the proportion of patients with ROA was not associated with HbA1c levels (16.4% [65/396], 17.7% [23/130], 14.3% [8/36], P = 0.694, Fig. 1b)

Prevalence of ROC, ROA by HbA1C category. (a) The prevalence of ROC. ROC is defined as ADP inhibition rate of less than 30%. (b) The prevalence of ROA. ROA is defined as AA inhibition rate of less than 50% assessed by TEG. ROC resistance to clopidogrel, ADP adenosine diphosphate, ROA resistance to aspirin, AA arachidonic acid, TEG thromboelastographic.

According to the univariate analysis model, both HbA1c > 8.5 and 6.5 ≤ HbA1c ≤ 8.5 were significantly associated with the ROC. However, after adjustment for other covariables, only HbA1c > 8.5 remained significantly associated with ROC (3.356 [1.231, 9.234], p = 0.009; Table 2).

In the multi-variables adjusted model, ROC was observed among those with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 [3.215 (1.219, 8.589), P = 0.013; Table 2].

The impact of hemoglobin A1c levels and ROC on patient outcomes

According to the Cox regression model adjusted for ROC only, compared with HbA1c < 6.5, HbA1c > 8.5 was significantly associated with nonfatal MI (2.297 [1.275, 4.137], P = 0.006), ischemia-driven revascularization (3.845 [2.082, 7.101], p < 0.001) and MACE (3.142 [2.346, 4.206], < 0.001), but not all-cause mortality (2.371 [0.551, 10.190], 0.246), even after fully adjusting for female sex, HbA1c category, prior MI, hypertension, baseline hsCR, BNP, TNI, hemoglobin, and acute coronary syndrome, whereas ROC was not (Table 3).

In terms of the endpoints of all-cause mortality and nonfatal MI, there was no difference in event rates or HR between the HbA1c < 6.5 and 6.5 ≤ HbA1c ≤ 8.5 groups, whereas the HbA1c ≤ 6.5 to 8.5 group had a greater risk of adverse events regarding ischemia-driven revascularization (2.336 [1.379, 3.958], p = 0.002) and overall MACE (1.657 [1.098). 2.500], p = 0.016), which was mainly driven by ischemia-driven revascularization, compared to the HbA1c < 6.5 group. Furthermore, the difference remained after adjusting for female gender, HbA1c category, prior MI, Hypertension, baseline hsCR, BNP, TNI, Hemoglobin and Acute coronary syndrome in a cox regression analysis model (Table 3). When HbA1c was considered a continuous variable in the Cox regression analysis, the HbA1c levels were associated with a 1.287-fold (1.287 [1.215, 1.365], P = 0.001) increase in the incidence of MACE. Regardless of whether it was a categorical variable or continuous variable, higher HbA1c levels were significantly associated with an increased risk of nonfatal MI and ischemia-driven revascularization.

The all-cause mortality and rates of nonfatal MI and ischemia-driven revascularization in all participants were 1.8% (33 of 1621), 5.0% (92 of 1621) and 11.4% (209 of 1621), respectively. The K‒M curve showed that elevated HbA1c levels were associated with an increasing rate of MACE (log rank, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2A). In addition, higher HbA1c levels were significantly related to a greater incidence of nonfatal MI (log rank, p = 0.027) (Fig. 2B) and ischemia-driven revascularization (log rank, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2D). However, there was no association between HbA1c levels and all-cause mortality (log rank, p = 0.063) (Fig. 2C). In subgroup analysis of association between HBIaC level and MACE, there were 1140 patients with non-diabetics. The highest HR values were still observed among those with high HbA1c levels with no significant interaction in subgroups. In addition, the results were almost consistent in subgroup of age, gender, obesity status, hypertension status, as shown in Table 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves showing the association between HBIaC groups and clinical outcomes. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves showing the association between MACE and HBIaC groups. (B) Kaplan–Meier curves showing the association between Non-fatal MI and HBIaC groups. (C) Kaplan–Meier curves showing the association between all-cause mortality and HBIaC groups. (D) Kaplan–Meier curves showing the association between ischemia-driven revascularization and HBIaC groups. MACE major adverse cardiovascular event, MI myocardial infarction.

The RCS was drawn to explore the nonlinear relationship between HbA1c levels and the incidence of MACEs as a continuous variable (nonlinear P < 0.001) based on a Cox regression model. Finally, the results revealed that HbA1c levels were positively associated with the risk of MACE after adjustment for female sex, age, smoking status, BMI, prior MI, hypertension, baseline hsCRP, BNP, TNI, hemoglobin, and acute coronary syndrome (Fig. 3).

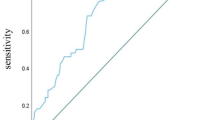

The efficacy of the use of the HbA1c level as a continuous variable for predicting MACEs is demonstrated in Fig. 4. The AUC of HbA1c levels for 36-month MACE was 0.636 (0.612, 0.624, P < 0.001).

Discussion

In this large-scale retrospective study of patients in the Chinese population after intracoronary stenting with available HbA1c values and platelet reactivity tests, ROC after clopidogrel administration tested by TEG was not frequent, with 9.3% of patients showing an inhibition rate of ADP < 30% after PCI. The proportion of patients with ROC progressively increased with increasing HbA1c levels. However, ROA, defined as an inhibition rate of AA less than 50%, occurred more frequently in 16.5% of patients after the administration of a loading dose of aspirin, but was not associated with HbA1c levels. As we know, Clopidogrel is a pro-drug that requires biotransformation into its active metabolite through cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, particularly CYP2C19. Elevated HbA1c levels, indicative of poor glycemic control, may impact this metabolic pathway in several ways. Firstly, Diabetes and high HbA1c levels were known to affect CYP enzyme activity and could lead to altered CYP enzyme function, including CYP2C19. This might impair the conversion of clopidogrel into its active form, which irreversibly inhibits binding of ADP to the P2Y12 receptor on the platelet, thereby contributing to clopidogrel resistance. Additionally, poor glycemic control could lead to increased platelet activation and aggregation due to oxidative stress and metabolic derangements18. In contrast, our study did not find a significant association between HbA1c levels and aspirin ROA. Several reasons could explain this discrepancy. Firstly, the mechanism of the action of aspirin is briefly mentioned as following that aspirin irreversibly acetylates the platelet cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) enzyme, which prevents the formation of thromboxane A2, a platelet activator, and could also interfere with platelet function by impairment of neutrophil-mediated platelet activation. Therefore, ROA could occur more frequently owing to any abnormality in any of pathway mentioned19. Furthermore, ROA is typically associated with genetic factors or the presence of specific platelet disorders rather than metabolic derangements alone. It is less likely to be affected by chronic glycemic control compared to ROC20.

We found that HbA1c levels were significantly related to nonfatal MI, ischemia-driven revascularization and overall MACE at the 36-month follow-up in the adjusted model, and the level of glycemic control was progressively associated with the ROC after adjustment for covariables. Furthermore, when HbA1c was treated as a continuous variable, the HbA1c level increased the MACE rate by 1.287-fold (1.287 [1.215, 1.365], P = 0.001). Conversely, the ROC had no significant relationship with adverse cardiovascular events after adjusting for HbA1c and other cardiovascular risks.

We performed RCS analysis to detect the association between HbA1c and MACE when HbA1c was considered a continuous variable, in which the curve had no inflection point and the feature of a monotonicity function. The study results showed that higher HbA1c levels indicated a greater risk of MACE according to the adjusted model for other confounders. In addition, an ROC curve was drawn and showed that HbA1c had a moderate capacity to predict the incidence of MACE after PCI.

Our study suggested that although the proportion of ROC increased with increasing HbA1c levels, the association between ROC and adverse clinical events was driven by poor glycemic control, which forecasted nonfatal MI and ischemia-driven revascularization after coronary drug-eluting stent placement regardless of platelet reactivity. Therefore, our findings warranted efforts to intensify hypoglycemic therapy after PCI in patients with diabetes to reduce clinical cardiovascular events.

We found a strong relationship between HbA1c > 8.5 and ROC as well as adverse clinical events. These results agreed with the findings of Annunziata Nusca et al.21 in 35 patients with chronic coronary syndrome and diabetes who underwent PCI. In this study, glycemic control combined with glycemic variability appeared to correlate with high platelet reactivity, as tested by the VerifyNow assay after administration of a loading dose of clopidogrel, and predicted the incidence of adverse events with the highest diagnostic accuracy.

According to a subgroup analysis of the early PCI-CURE trial22 (clopidogrel in unstable angina to prevent recurrent events), the combination therapy of aspirin and clopidogrel in patients with non-ST elevation ACS who received PCI treatment significantly reduced adverse clinical events in patients without diabetes but exhibited no beneficial effect in patients with diabetes. This subgroup analysis suggested that despite the use of clopidogrel on platelet reactivity in patients with diabetes, the increased hazard of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients was not fully mitigated23,24. This finding suggested that new potent P2Y12 antagonists are needed to optimize post-PCI outcomes in patients with diabetes.

In a prespecified meta-analysis25 to assess post-PCI adverse cardiovascular outcomes and bleeding events associated with prasugrel versus clopidogrel, patients with ACS and diabetes showed a greater reduction in recurrent MI than patients without diabetes when prasugrel was prescribed compared with clopidogrel. The positive effects of prasugrel on platelet reactivity and outcomes in patients with diabetes did not increase the risk of major bleeding, implying that more intensive antiplatelet treatment provided by prasugrel may be particularly beneficial for patients with diabetes and ACS. In contrast, in another substudy of patients with ACS and diabetes in the PLATO trial26, ticagrelor, compared with clopidogrel, reduced adverse events in patients with ACS irrespective of glycemic control and diabetes status. In general, it must be noted that patients with diabetes have a greater rate of ischemia events than those without diabetes27,28,29, suggesting that newer potent P2Y12 antagonists are not sufficient to fully mitigate the increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events in diabetic patients after PCI.

Suboptimal glycemic control had been associated with heightened platelet reactivity7,8,9,10, thereby contributing to an augmented prothrombotic state and increasing the risk of adverse events. However, the clinical necessity of intensive antiplatelet treatment in patients with diabetes is still debated, and the beneficial effects might be specific to various P2Y12 inhibitors30,31. Although potent P2Y12 inhibition remains integral32,33, its efficacy in isolation appears limited in fully mitigating the amplified risk observed in this cohort. Regardless, optimizing glycemic control was still the most important measure to improve outcomes in diabetic patients undergoing PCI.

Limitations

There were several limitations in this study. First, this was a two-center cohort study rather than a randomized controlled trial; therefore, this study has some confounding factors and bias, weakening the validity of the conclusions in the overall population. Second, despite careful multivariate analysis and appropriate adjustment based on clinical knowledge and data-specific findings, the 3 groups of HbA1c levels varied in terms of patient characteristics. As a result, we cannot exclude the effects of residual and undetected confounders on our results. Third, testing for platelet reactivity was only performed at one time point, whereas a few studies34,35 have shown that platelet reactivity might dynamically change over time, indicating that serial testing could provide additional prognostic information. Fourth, several unmeasured confounders, including medication adherence, incomplete stent expansion and diffuseness of untreated coronary atherosclerosis, may affect the relationship between HbA1c and post-PCI events.

Conclusion

In this large-scale study in a Chinese population, HbA1c levels were positively related to ROC but not to ROA, but the adverse effect on clinical outcomes was driven by elevated HbA1c, which forecasted nonfatal MI and ischemia-driven revascularization, constituting an argument to intensify glycemic control in subjects with diabetes after intracoronary stent placement. However, care must be taken because hypoglycemia requires medical treatment, and weight gain is accompanied by intensive glycemic control.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the protection of patients’ privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mao, Y., Zhu, B., Wen, H., Zhong, T. & Bian, M. Impact of platelet hyperreactivity and diabetes mellitus on ischemic stroke recurrence: a single-center cohort clinical study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 17, 1127–1138 (2024).

Sagar, R. C., Naseem, K. M. & Ajjan, R. A. Antiplatelet therapies in diabetes. Diabet. Med. 37(5), 726–734 (2020).

Vazzana, N., Ranalli, P., Cuccurullo, C. & Davì, G. Diabetes mellitus and thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 129(3), 371–377 (2012).

Campo, G. et al. Long-term clinical outcome based on aspirin and clopidogrel responsiveness status after elective percutaneous coronary intervention: a 3T/2R (tailoring treatment with tirofiban in patients showing resistance to aspirin and/or resistance to clopidogrel) trial substudy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 56, 1447e1455 (2010).

Price, M. J. et al. Platelet reactivity and cardiovascular outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention: a time-dependent analysis of the gauging responsiveness with a VerifyNowP2Y12 assay: impact on thrombosis and safety (GRAVITAS). Trial Circ. 124, 1132–1137 (2011).

Nusca, A. et al. Glycemic control in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: what is the role for the novel antidiabetic agents? A comprehensive review of basic scienceand clinical data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7261 (2022).

Kim, H. S. et al. Implication of diabetic status on platelet reactivity and clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation: results from the PTRG-DES consortium. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22(1), 245 (2023).

Her, A. Y., PTRG-DES Consortium investigators et al. Platelet function and genotype after DES implantation in East Asian patients: rationale and characteristics of the PTRG-DES Consortium. Yonsei Med. J. 63(5), 413–421 (2022).

Andersson, C. et al. Relationship between HbA1c levels and risk of cardiovascular adverse outcomes and all-cause mortality in overweight and obese cardiovascular high-risk women and men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 2348–2355 (2012).

Sinning, C. et al. Association of glycated hemoglobin A1c levels with cardiovascular outcomes in the general population: results from the BiomarCaRE (Biomarker for Cardiovascular Risk Assessment in Europe) consortium. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20(1), 223 (2021).

Kim, H. et al. Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease among type 2 diabetes patients according to average and visit-to-visit variations of HbA1c levels during the first 3 years of diabetes diagnosis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 38(4), e24 (2023).

Mangiacapra, F. et al. Lack of correlation between platelet reactivity and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients treated with aspirin and clopidogrel. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 32, 54–58 (2011).

Shlomai, G. et al. High-risk type-2 diabetes mellitus patients, without prior ischemic events, have normal blood platelet functionality profiles: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 14, 80 (2015).

Joelle Singer, A. W. et al. Effect of intensive glycemic control on platelet reactivity in patients with long-standing uncontrolled diabetes. Thromb. Res. 134(1), 121–124 (2014).

Xu, L. et al. Association between HbA1c and cardiovascular disease mortality in older Hong Kong Chinese with diabetes. Diabet. Med. 29, 393–398 (2012).

Yao, Y. et al. Head-to-head comparison of two point-of-care platelet function tests used for assessment of on-clopidogrel platelet reactivity in Chinese acute myocardial infarction patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Chin. Med. J. (Engl). 129(19), 2269–2274 (2016).

Madsen, E. H. et al. Long-term aspirin and clopidogrel response evaluated by light transmission aggregometry, verifynow, and thrombelastography in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin. Chem. 56(5), 839–847 (2010).

Chang, R. et al. Relationship between CYP2C19 polymorphism and clopidogrel resistance in patients with coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke in China. Genet. Res. (Camb). 2022, 1901256 (2022).

Kim, J. et al. Molecular genomic and epigenomic characteristics related to aspirin and clopidogrel resistance. BMC Med. Genom. 17(1), 166 (2024).

Virk, H. U. H. et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy: a concise review for clinicians. Life (Basel) 13(7), 1580 (2023).

Nusca, A. et al. Incremental role of glycemic variability over HbA1c in identifying type 2 diabetic patients with high platelet reactivity undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 18(1), 147 (2019).

Mehta, S. R. et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 358, 527—533 (2001).

Ma, Q. et al. Clinical outcomes and predictive model of platelet reactivity to clopidogrel after acute ischemic vascular events. Chin. Med. J. (Engl) 132(9), 1053–1062 (2019).

Bergmeijer, T. O. et al. Effect of CYP3A4*22 and PPAR-α genetic variants on platelet reactivity in patients treated with clopidogrel and lipid-lowering drugs undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Genes (Basel) 11(9), 1068 (2020).

Bundhun, P. K. & Huang, F. Post percutaneous coronary interventional adverse cardiovascular outcomes and bleeding events observed with prasugrel versus clopidogrel: direct comparison through a meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 18(1), 78 (2018).

James, S. et al. Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes and diabetes: a substudy from the PLATelet inhibition and patient outcomes (PLATO) trial. Eur. Heart J. 31, 3006–3016 (2010).

Hiromine, Y. et al. Poor glycemic control rather than types of diabetes is a risk factor for Sarcopenia in diabetes mellitus: the MUSCLES-DM study. J. Diabetes Investig. 13(11), 1881–1888 (2022).

Raghavan, S. et al. Diabetes mellitus-related all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a national cohort of adults. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8(4), e011295 (2019).

Tomic, D., Shaw, J. E. & Magliano, D. J. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18(9), 525–539 (2022).

Chyrchel, B. K. et al. Association of ADP-induced whole-blood platelet aggregation with serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with coronary artery disease when receiving maintenance ticagrelor-based dual antiplatelet therapy. J. Clin. Med. 12, 4530 (2023).

Kumar, A. et al. Comparative effectiveness of ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel for secondary prophylaxis in acute coronary syndrome: a propensity score-matched cohort study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 113(2), 401–411 (2023).

van der Hoeven, N. W. et al. Platelet inhibition, endothelial function, and clinical outcome in patients presenting with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction randomized to ticagrelor versus prasugrel maintenance therapy: long-term follow-up of the rEDUCE-MVI trial. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9(5), e014411 (2020).

Coughlan, J. J. et al. Ticagrelor or prasugrel for patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with percutaneous coronary intervention: a prespecified subgroup analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 6(10), 1121–1129 (2021).

Jaitner, J. et al. Stability of the high on-treatment platelet reactivity phenotype over time in clopidogrel-treated patients. Thromb. Hemost. 105, 107–112 (2011).

Verma, S. S. et al. Genomewide association study of platelet reactivity and cardiovascular response in patients treated with clopidogrel: a study by the International Clopidogrel Pharmacogenomics Consortium. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 108(5), 1067–1077 (2020).

Funding

This research was supported by Health Commission of Jiading District, Shanghai (2022-KY-03, 2021-KY-11).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YLW, XJ, WZL, Ml were involved in the design of this study; YLW, XJ contributedto manuscript writing; LJJ and HYJ were reponsible for data collection anddata management; YLW, HYJ contributed to the statistical analysis; YLW, ML and WZLparticipated in data review and manuscript revision. All authors havereviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocols were approval by the Ethics Committee of Jiading Branch of Shanghai General Hospital and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y., Jiang, X., Jiang, L. et al. Impact of haemoglobinA1c on platelet reactivity and cardiovascular outcomes in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation. Sci Rep 14, 29699 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81537-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81537-1