Abstract

Musculoskeletal discomfort among children carrying school bags is an increasingly significant problem. This study sought to determine the prevalence and risk factors of musculoskeletal discomfort among Thai primary school students who carry excessively heavy school bags. We conducted cross-sectional descriptive research involving 489 primary school students (ages 7–12). We utilized the standardized Cornell Musculoskeletal Discomfort Questionnaire (CMDQ) to assess discomfort in various body regions. Measurements included student weight, school bag weight, and the angles of neck and trunk inclination. Logistic regression was used to analyze factors influencing musculoskeletal discomfort. The results showed that the majority of students had musculoskeletal discomfort (66.67%). The average relative weight of the school bags was 17.46 ± 6.02%. Significant risk factors for musculoskeletal discomfort included being female (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.12–3.10), being in grades 1–3 (AOR = 0.221, 95% CI = 0.05–0.91), carrying bags for more than 20 min per day (AOR = 28.87, 95% CI = 8.93–93.31), not storing books at school (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.07–3.95), and carrying a school bag weighing > 10% of the student’s body weight (AOR = 65.46, 95% CI = 14.73-290.93). Additionally, neck and trunk inclinations > 20 degrees were associated with increased discomfort (AOR = 3.25, 95% CI = 1.89–5.57; AOR = 3.26, 95% CI = 1.58–6.70). The prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort was higher in Thai primary school students. Female, Grades 1–3, carrying bags exceeding 20 min/day, carrying a school bag weighing > 10% of the student’s body weight, and neck and trunk inclinations > 20 degrees were predictor variables for musculoskeletal discomfort. Thus, collaborative efforts from educational institutions, educators, parents, and students are essential in addressing this issue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are injuries affecting muscles, ligaments, nerves, and the circulatory system, often resulting from various inflammations and degenerative changes1. These disorders can manifest as either acute or chronic issues, significantly incapacitating those affected2, and leading to high costs for health systems3. MSDs are among the most common causes of disability worldwide, affecting approximately 1.71 billion people globally4. In 2019, MSDs resulted in around 1.71 billion common instances and 149 million years lived with disability5. Back pain, particularly low back pain (LBP), is prevalent and often stems from MSDs of the spine, posing a significant and growing health concern among children and adolescents6. Back pain can arise from an identifiable condition (specific back pain) or without an apparent cause (non-specific back pain). As of 2020, the global population of children aged 0 to 14 was approximately 1.98 billion7. According to research conducted by The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work (EU-OSHA), MSD prevalence is notably high among schoolchildren and young individuals (aged 7 to 26.5 years), with an average prevalence rate of 30%8.

School bags are frequently essential for transporting educational materials9. However, the weight of these bags has significantly increased due to the necessity of carrying academic materials10. Some researchers suggest that heavy backpacks may exacerbate children’s back problems11,12. The long-term risk of low back pain and other musculoskeletal issues is believed to increase with the use of heavy school backpacks, leading to poor posture, changes in trunk posture, and ultimately lower back pain and impaired balance12,13. In India, a study reported a 53.9% prevalence of back pain in children over the last month11. Similarly, in northwest England, the prevalence of low back pain among schoolchildren aged 11 to 14 years was 24% over a one-month period14. Several comprehensive studies have attempted to identify potential risk factors for back pain in young children, focusing on factors such as school bags, puberty, weight status, and physical activity15,16,17,18 Moreover, several studies have investigated the effects of increasing backpack weights on biomechanical factors, assessed through ground reaction force during walking while carrying a bag, to establish a safe weight limit for schoolchildren’s19. The suggested load limit for students to carry ranges from 5 to 20% of their total body weight20,21,22. However, there is still no consensus on guidelines for backpack weight and other associated factors.

In Thailand, the Child Safety Promotion and Injury Prevention Research Center (CSIP) has reported that 80% of primary school children carry heavy bags that exceed 10% of their body weight23. Additionally, the prevalence of pain experienced while carrying a school bag varies significantly by the type of bag. On average, school bags weighed between 11.14% and 11.72% of body weight among children aged 6–12 years during 2011-201224. Despite these findings, there is a notable lack of research on the prevalence of musculoskeletal back pain and its association with factors in Thailand’s primary schools. Furthermore, the Thailand Office of the Basic Education Commission recommends a weight limit for school bags, suggesting that children’s school bags should not exceed 15% of their body weight. This guideline has been in place for over ten years. However, limited information is available on the current use of school bags and the actual weight of bags carried by students, especially those who commute daily. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort and examine risk factors among Thai primary school students carrying excessive school bags. The findings of this study will provide valuable information for designing appropriate intervention strategies to prevent potential issues with children’s development and maturation.

Materials and methods

Study design, setting, and participants

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted on primary public school students, typically aged between 7 and 12 years, enrolled in Grades 1 to 6 during the 2023 academic year. This study took place from August to September 2023 at three public schools in Muang, Nakhon Si Thammarat, Thailand.

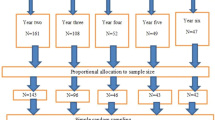

Sample size and sampling technique

The sample size was determined using the Cochran Formula25. The sample size was calculated using the formula \(\left( {n = [p(1 - p)z^{2} ]/e^{2} } \right)\). In this formula, n is the number of participants required, p is the expected proportion = 0.6626, z is 1.96 in 95% confidence interval, q = 1 - p, and e is the acceptable sampling error (0.05). Therefore, the sample size of this study was 345 students. Participants were purposively selected from three competitive primary public schools in Nakhon Si Thammarat province. Students from each school were chosen using a multi-stage random sampling method, stratified by grade and sex.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were children aged 7–12 attending primary school, encompassing both sexes, who had the ability to self-ambulate and could wear the school bag symmetrically on both shoulders. Exclusion criteria included children with intellectual disabilities, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, hemiparesis, diabetes mellitus, heart and circulatory diseases, respiratory system disorders, neurovascular problems, and congenital problems; a history of fractures or injuries to the lower extremities within the past year; a history of trauma to the spine, shoulders, or neck, carrying a bag on one side; as well as those lacking signed parental consent or legal representation; and those who did not give consent to participate in the study.

Data collection and procedure

Questionnaire

The questionnaires collected demographic information along with details about the sex, age, grade, underlying disease, exercise, hobby, duration of carry bag (min/day), perception of heaviness, keeping a book in school, assistance with parent baggage, and musculoskeletal discomfort. Specific questions about musculoskeletal symptoms in various body regions were based on the standardized Cornell Musculoskeletal Disorders Questionnaire (CMDQ)27, which includes a body map to identify areas with symptoms. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency of discomfort using a scale (Never = 0, 1–2 times/week = 1.5, 3–4 times/week = 3.5, Once every day = 5, Several times every day = 10) and to rate the severity of discomfort on a scale from 1 (slightly uncomfortable) to 3 (very uncomfortable). A pain level of at least “moderately uncomfortable” was used as a severity threshold for determining prevalence and frequency. Additionally, respondents rated the extent to which discomfort interfered with their studies from 1 (no interference) to 3 (substantial interference). The total discomfort score was calculated using the formula: frequency × discomfort × interference = discomfort score27,28. MSD was categorized as mild, moderate, and severe based on reported discomfort and as no discomfort when none was reported. A CMDQ score of 1.5 indicated mild discomfort, scores ranging from 1.6 to 10.5 indicated moderate discomfort, and scores above 10.5 indicated severe discomfort. A CMDQ score of 0 signified no discomfort29. Participants were given a brief overview of the CMDQ and asked to complete it independently. Investigators assisted students by simplifying questions and clarifying any uncertainties. The questionnaires underwent an instrument quality evaluation, achieving a conformance score of 0.81 for the Index of Item-Objective Congruence (IOC). With a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91, they demonstrated good validity and reliability in assessing musculoskeletal discomfort.

Student weight/height and school bag weight measurements

A digital electronic scale was used to measure the weight of each participant’s school bag, including any additional items they carried. Before data collection began, the scale was calibrated using a range of known weights to ensure accuracy to 0.01 kg. The school bag weight was measured twice to establish the average weight. Participants’ body weight was recorded while they stood barefoot on the digital weighing machine. The weight of the fully loaded school bag was noted in kilograms. To calculate the bag weight/body weight%, the weight of the school bag was divided by the participant’s body weight and then multiplied by 100. School bags were weighed daily from Monday to Friday to determine the average weight for each participant.

For height measurements, a stadiometer was used. Participants stood upright with their bottom, shoulder blades, and feet aligned against the back of the stadiometer. The horizontal bar was adjusted downward until it lightly touched the top of the participant’s head, ensuring any hair that might obstruct the measurement was flattened. Height measurements were recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm. Two measurements were taken, and the average of the two closest values, within 0.2 cm (0.25 inch), was used.

The relative school bag weight, expressed as a percentage of the participant’s body weight (%BW), was determined using the bag weight to body weight%.

The neck and trunk inclination

The photographic method was used to assess the posture of each subject, with adhesive markers placed on anatomical landmarks after proper exposure of each landmark. Neck and trunk inclinations were measured using Kinovea Software during the 5-minute bag-carrying capture. Kinovea, a free 2D motion analysis software, is noted for its validity (0.79) and reliability (0.99)30. This software facilitates the measurement of neck and trunk angles. In general, abduction refers to elevation in the frontal plane, while flexion indicates a rise parallel to the sagittal plane31,32. Measurement specifics were taken according to ISO standards32,33. The procedure started by marking two points on the neck, e.g. close to the earlobe and close to the lateral corner of the eye. The neck angle was defined as the difference between the angle in reference posture (Fig. 1a) and the angle in the posture while carrying a bag (Fig. 1b). Two points of the trunk were considered at the spinous process of 7th cervical vertebra and the upper edge of the greater trochanter (hip). The trunk angle was defined as the difference between the angle in reference posture (Fig. 1c) and the angle in the posture while carrying a bag (Fig. 1d).

Statistical analysis

Data were recorded and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25 (IBM, New York, USA). The data were evaluated for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests. The prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort, school bag weight, and school bag usage behaviors were assessed using frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation (SD), or median. Differences in school bag weight by grade and sex were evaluated using an independent t-test. The mean difference in neck and trunk angles with and without a load in school-aged students was conducted using a paired t-test. The mean difference in relative school bag weight was investigated using the ANOVA test. Bivariate relationships between the independent variable and musculoskeletal discomfort were investigated using the Chi-square test. A logistic regression model was applied for predictive analysis to determine the association between the independent variable and musculoskeletal discomfort. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee at Walailak University, with the approval number WUEC-23-203-1 August 17, 2023. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants. Participants were informed that they could decline to answer any questionnaire item and could withdraw from the study at any time. Written informed consent was acquired from the participant’s parent for the release of any potentially identifiable photographs or data in this research.

Results

General characteristics

The questionnaire achieved a 100% response rate. Out of the total sample size of 489 participants, 276 individuals (56.44%) identified as female, while 213 individuals (43.56%) identified as male. The majority of participants (54.60%) were aged between 7 and 9 years, with students from grades one through six included in the research. Most participants reported having no underlying diseases (88.75%), although a significant proportion engaged in regular exercise (65.44%) and pursued hobbies (65.85%). On average, participants reported carrying bags for 19.04 ± 12.05 min per day, and the majority perceived the weight of school bags as heavy (71.57%). A significant percentage of students admitted to lacking places for books or notebooks in school (82.21%). However, most parents helped their children reduce the weight of their bags (58.28%). The average relative school bag weight was 17.46 ± 6.02%, and a majority of students reported experiencing musculoskeletal discomfort (66.67%), as detailed in Table 1.

The prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort

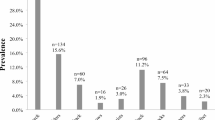

The prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort among children carrying school bags was 66.67%. The top five reported areas of musculoskeletal discomfort were the right shoulder (45.40%), left shoulder (45.40%), neck (42.94%), upper back (27.81%), and lower back (24.13%) (Fig. 2).

School bag weight

The average weight of school bags was 5.62 ± 1.46 kg. Among all grade levels, sixth-grade students had the highest average school bag weight (6.69 ± 1.27 kg). There was a statistically significant difference in school bag weight across grade levels (p < 0.001). These findings indicated that the school bag weight of Grade 1 students was significantly different from that of students in all other grades (p < 0.001). Furthermore, there were statistically significant differences between the school bag weights of second-grade students and those of grades five (p < 0.001) and six (p < 0.001). Similarly, significant differences were found between the school bag weights of third-grade students and those of grades five (p < 0.001) and six (p < 0.001). Additionally, the school bag weight of fourth-grade students differed significantly from that of students in grades five (p < 0.001) and six (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Figure 4 illustrates the comparison of school bag weight differences by sex, revealing that female students carried heavier bags compared to male students, with statistical significance at p < 0.05.

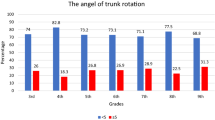

Inclination of neck and trunk angle

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the mean neck and trunk angles in an individual child, both before and after carrying a school bag. The average neck angle before carrying a school bag was 51.26 ± 9.09 degrees, which increased to 72.66 ± 17.86 degrees after carrying the bag, with a statistically significant difference at p < 0.001. Similarly, the average trunk angle increased from 4.26 ± 2.50 degrees before carrying to 18.63 ± 8.65 degrees after carrying, also showing a statistically significant difference at p < 0.001.

When comparing the difference in neck and trunk angle deviations with various relative school bag weights, it was determined that there was no significant difference between neck angle and relative school bag weight. However, differences in trunk angle were observed between bags weighing less than 10% BW and those weighing 11–15% BW, as well as between bags weighing less than 10% BW and those weighing more than 20% BW, as shown in Table 3.

Factors associated with musculoskeletal discomfort

Table 4 presents univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of factors influencing musculoskeletal discomfort. In the univariate analysis, age group, grade group, duration of carrying a bag, perceived heaviness, keeping a book in school, relative weight (% body weight), neck inclination (degrees), and trunk inclination (degrees) were significantly associated with a history of in the last seven days (p < 0.05). In the multivariate logistic regression, significant predictors of musculoskeletal discomfort in the last seven days included being female, being in grades 1–3, carrying bags for more than 20 min per day, not keeping a book in school, school bag weight exceeding 10% of body weight, neck angles greater than 20 degrees, and trunk angles greater than 20 degrees (p < 0.05).

Furthermore, students who carry backpacks weighing more than 10% of their body weight are 65 times more likely to experience musculoskeletal discomfort compared to those carrying lighter bags (AOR = 65.46, 95% CI = 14.73-290.93). Students who carry a school bag on both shoulders for more than 20 min per day are 30 times more likely to experience musculoskeletal discomfort than those who carry their bags for less than 20 min (AOR = 28.87, 95% CI = 8.93–93.31). Deviations in neck and trunk angles of more than 20 degrees significantly increase the risk of severe discomfort, being three times more likely than deviations of less than 20 degrees (AOR = 3.25, 95% CI = 1.89–5.57; AOR = 3.26, 95% CI = 1.58–6.70). Students who do not store their books at school are twice as likely to report musculoskeletal discomfort as those who do (AOR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.07–3.95). Students in lower grades (G.1–3) were more likely than those in higher grades (G.4–6) to experience musculoskeletal discomfort (AOR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.05–0.91). Additionally, females are nearly twice as likely as males to experience musculoskeletal discomfort (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI = 1.12–3.10) (Table 4).

Discussion

This research aimed to examine the prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort among Thai primary school students. The findings indicated that nearly two-thirds of students experienced musculoskeletal discomfort, while the prevalence was 39.4% in Saudi Arabia and 30.8% in Kuwait, respectively34,35. Almost a decade ago, a study in Thailand found that 66.6% of Thai students had musculoskeletal pain26. This estimate is comparable to that in the present research, although the previous study focused only on secondary school students. A study conducted in India reported that 58.3% of children have musculoskeletal disorders, which were 3.295 times more prevalent among children who carried heavy school bags compared to those who did not36. For the twenty body parts examined, the highest prevalence of musculoskeletal symptoms was reported for complaints in the right and left shoulders, followed by the neck, upper back, and lower back. This pattern aligns with findings from a study by Deesungnern S. and Polyong C. P26,37. , who noted that the most commonly affected areas—shoulders, neck, lower back, and upper back—are typically strained by carrying large school bags. Similar studies suggest that the trapezius and erector spinae muscles are most affected when carrying a school bag38,39. When a student wears a heavy bag on both shoulders, pressure is applied to both shoulders through the shoulder straps. The contact pressure beneath the backpack’s shoulder straps increases significantly when carrying weights ranging from 10 to 30% of body weight40. This contact pressure exceeds the threshold (about 30 mm Hg) required to inhibit skin blood flow41. School bag straps often stress the shoulder in the front, directly over the brachial plexus, axillary artery, and vein42. For neck pain, when students have to carry heavy bags, their heads and bodies bend forward to preserve balance. Forward head position requires bending of the lower cervical spine and extension of the upper cervical spine. It is often associated with extended scapulae and enhanced thoracic kyphosis. Repeated stress may create lifelong impairment or chronic discomfort at an early age43,44.

Musculoskeletal discomfort experienced by students who carry bags may be attributed to various risk factors. Based on the findings of this research, many risk variables have been identified as significant contributors to the development of musculoskeletal problems, including sex, grade level, duration of carrying the bag, keeping a book in school, relative school bag weight, and the angles of neck and trunk inclinations.

Sex

This study demonstrated that women are more exposed to ergonomic risk factors than men. One cohort study identified sex as a potential predictor of back pain episodes, with females showing an increased prevalence of back pain45. According to the data, females typically carry bags exceeding 10% BW and weighing 5.75 kg, while males carry bags weighing 5.45 kg. This disparity may be attributable to physiological differences typical in adolescents as they approach puberty, when skeletal and muscular development is characterized by rapid growth. Gender differences in strength become more pronounced, with males generally possessing greater muscle mass than females37. Chinese research found that female students had a higher prevalence of neck and shoulder pain than male students46. They proposed several potential reasons for these findings: (1) Males might have a higher pain threshold; (2) Girls experience unique hormonal changes during puberty; (3) Females often face greater mental stress; (4) A higher heritability of neck and shoulder pain is observed in females.

Grades

This study revealed that students in grades 1–3 experienced slightly higher levels of musculoskeletal pain than those in grades 4–6. This suggests that younger children are more susceptible to musculoskeletal pain (MSD) while carrying a bag compared to their older peers. These findings contrast with previous research47,48 that showed a positive correlation between older age or higher academic grades and increased susceptibility to MSD, unlike younger students or those with lower grades. This discrepancy may be due to younger children not having fully developed their skeletal and muscular systems as much as older children who are approaching puberty, a period of rapid development. The musculoskeletal system undergoes significant changes in structure, biomechanics, and motor control during childhood before reaching a state of stability during maturity, particularly adolescence49. This concern is further underscored by the excessive weight of the bags carried by students in Thailand. In comparison, Thai children’s average baggage weight exceeded that of Maltese students of the same grade, and the weight of bags carried by Thai children was comparable to that of secondary school students50.

Duration of carrying bag

According to the study’s findings, students carry their bags for an average of 20 min per day. Those who carry their bags for more than 20 min are at a significantly higher risk of developing musculoskeletal pain—approximately 30 times higher than students who carry their bags for less than 20 min per day. This is similar to findings by Haselgrove et al., where nearly half of all teenagers reported carrying their schoolbag for more than 30 min daily51. High perceived fatigue was linked to longer durations of carrying a bag, such as on the bus for more than 30 min each day. Extended periods of carrying a school bag can affect cervical, shoulder, and lumbar posture, potentially contributing to the development and persistence of MSDs, according to the findings of many research studies52,53. According to research by Polyong C. P., students who carried a bag for more than 20 min faced a 3.3, 14.5, and 4.6 times greater risk of experiencing neck, shoulder, and upper back discomfort, respectively, compared to those who carried a bag for less than 10 min37. The duration of carrying often depends on the distance between the student’s home and their school, thus the longer the distance, the higher the risk of musculoskeletal pain.

Keeping books at school

More than 80% of children do not store schoolbooks at school. Despite schools providing lockers or space under the desk, children and their parents often prefer carrying books home due to fears of losing them and needing them to complete homework or for review. Consequently, children end up carrying large, heavy bags. In recent years, many schools have removed lockers due to concerns over security and vandalism. Anecdotal evidence indicates that students are frequently required to carry their fully loaded backpacks for extended periods durations54. Although lockers are available in all secondary schools in Malta, 46% of the students reported not having enough time to access them, forcing them to carry all necessary items from one classroom to another. As the number of subjects studied at secondary school increases, so does the volume of materials students must carry50. Reviews have suggested the installation of school lockers to reduce load exposure, which could help prevent the development or exacerbation of musculoskeletal issues55,56. Therefore, lockers should be conveniently located, secure, accommodate a sufficient number of students, and allow ample time for students to utilize them effectively56.

Relative school bag weight (%BW)

According to the research findings, up to 90% of all students carried bags weighing more than 10% of their body weight. There was an extremely significant correlation between carrying bags over 10% of body weight and experiencing musculoskeletal discomfort. Ideally, the weight of a school bag should not exceed 10-15% of the body weight. This guideline is based on the physiological and biomechanical effects associated with carrying heavy school bags57,58. However, this limit is often exceeded. Studies across various global regions have reported that a significant percentage of school-aged children carry school bags exceeding 10% of their total body weight59. Back pain is statistically related to the bag weight to body weight ratio, with every 1% increase in this ratio raising the chance of experiencing back discomfort50. In addition to books and notebooks, children often carry extra items such as pencil cases, water bottles, and tablets in their school bags. From student interviews, it was found that typically 1–2 books/notebooks are not used in class. To reduce the unnecessary weight children, carry daily, it is important to organize the class schedule effectively, facilitate communication between teachers and students to ensure only necessary books and notebooks are brought to school, and manage children’s overall workload and homework.

Inclined neck and trunk angles

The research found a difference in neck and trunk angles before and after carrying a bag. Musculoskeletal discomfort is also influenced by a neck and trunk inclination exceeding 20 degrees relative to the reference point. Consistent with findings from Li et al., walking for 20 min while carrying a load of 20% of body weight resulted in a significantly higher trunk inclination angle60. In another study, significant differences were observed in trunk angle, head angle, and lower extremity joint mechanics between carrying a backpack and during load-free walking (p.05)61. Notably, our study discovered that the trunk angle increased when carrying a bag weighing 15–20% BW compared to a bag of 10% BW. In contrast, for a bag weight of 25% BW, the trunk angle decreased by an average of 14° compared to the no-load condition, while the head angle increased by 13°61. There was more forward trunk and neck lean for the loaded bag than for the unloaded bag. This likely resulted from the posterior loading of the bag, causing participants to lean forward, placing their center of gravity (COG) within the base of support to compensate for the posterior pull of the load62.

One of the strengths of this study is the substantial participation of parents and children, resulting in a larger sample size than initially anticipated. We also measured the weight of the school bags on each of the five weekdays, ensuring that the average weight recorded was as close to reality as practically possible. However, there are limitations to this study. Given that a cross-sectional methodology was employed, it was not possible to analyze the causes and effects of every component thoroughly. Additionally, the musculoskeletal discomfort questionnaire was based on self-administered CMDQ items that involved children. Despite the instrument undergoing reliability testing and researchers conducting interviews with young children, there remains a need to be aware of potential biases introduced by self-reporting.

Conclusions

Primary school students in Thailand experienced significant musculoskeletal discomfort, with many carrying bags weighing over 10% of their BW. Significant predictors of musculoskeletal discomfort included being female, being in grades 1–3, carrying bags for more than 20 min per day, not keeping books in school, carrying a school bag weight exceeding 10% of BW, and incline neck and trunk angles greater than 20 degrees. Although musculoskeletal issues are complex, carrying heavy school bags is likely a contributing factor and may represent an overlooked daily challenge for Thailand’s primary school children. The collaborative efforts of educational institutions, educators, parents, and students are crucial in addressing this issue. Potential measures include implementing a well-structured class schedule, integrating various study areas, substituting traditional books with modern media, providing safe book storage facilities, promoting book collection initiatives, and reducing the burden of carrying heavy bags, especially for parents who need additional support.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding authors.

References

Zamri, E. N., Hoe, V. C. W. & Moy, F. M. Predictors of low back pain among secondary school teachers in Malaysia: a longitudinal study. Ind. Health. 58, 254–264 (2020).

Coggon, D. et al. Disabling musculoskeletal pain in working populations: is it the job, the person, or the culture? Pain 154, 856–863 (2013).

Lentz, T. A. et al. Factors associated with persistently high-cost health care utilization for musculoskeletal pain. PloS One. 14, e0225125 (2019).

Vos, T. et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet Lond. Engl. 380, 2163–2196 (2012).

Cieza, A. et al. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396, 2006–2017 (2020).

MacDonald, J., Stuart, E. & Rodenberg, R. Musculoskeletal Low Back Pain in School-aged children: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 171, 280–287 (2017).

Global. number of pupils in primary school. Statista (2019). https://www.statista.com/statistics/1227106/number-of-pupils-in-primary-education-worldwide/

Executive summary -. Musculoskeletal disorders among children and young people: prevalence, risk factors and preventive measures | Safety and health at work EU-OSHA. https://osha.europa.eu/en/publications/executive-summary-musculoskeletal-disorders-among-children-and-young-people-prevalence-risk-factors-and-preventive-measures

Layuk, S., Martiana, T. & Bongakaraeng, B. School bag weight and the occurrence of back pain among elementary school children. J. Public. Health Res. 9, 1841 (2020).

Sharan, D., Ajeesh, P. S., Jose, J. A., Debnath, S. & Manjula, M. Back pack injuries in Indian school children: risk factors and clinical presentations. Work 41, 929–932 (2012).

Oka, G. A., Ranade, A. S. & Kulkarni, A. A. Back pain and school bag weight - a study on Indian children and review of literature. J. Pediatr. Orthop. Part. B. 28, 397–404 (2019).

Toghroli, R. et al. Backpack improper use causes musculoskeletal injuries in adolescents: a systematic review. J. Educ. Health Promot. 10, 237 (2021).

Al-Khabbaz, Y. S. S. M., Shimada, T. & Hasegawa, M. The effect of backpack heaviness on trunk-lower extremity muscle activities and trunk posture. Gait Posture. 28, 297–302 (2008).

Watson, K. D. et al. Low back pain in schoolchildren: occurrence and characteristics. Pain 97, 87–92 (2002).

Lindstrom-Hazel, D. The backpack problem is evident but the solution is less obvious. Work Read. Mass. 32, 329–338 (2009).

Lardon, A., Leboeuf-Yde, C., Le Scanff, C. & Wedderkopp, N. Is puberty a risk factor for back pain in the young? A systematic critical literature review. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 22, 27 (2014).

Paulis, W. D., Silva, S., Koes, B. W. & van Middelkoop, M. Overweight and obesity are associated with musculoskeletal complaints as early as childhood: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. Off J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 15, 52–67 (2014).

Sitthipornvorakul, E., Janwantanakul, P., Purepong, N., Pensri, P. & van der Beek, A. J. The association between physical activity and neck and low back pain: a systematic review. Eur. Spine J. Off Publ Eur. Spine Soc. Eur. Spinal Deform Soc. Eur. Sect. Cerv. Spine Res. Soc. 20, 677–689 (2011).

Shasmin, H. N., Abu Osman, N. A., Razali, R., Usman, J. & Wan Abas, W. A. B. A Preliminary Study of Acceptable Load Carriage for Primary School Children. in 3rd Kuala Lumpur International Conference on Biomedical Engineering 171–174 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2007). doi: (2006). (eds. Ibrahim, F., Osman, N. A. A., Usman, J. & Kadri, N. A.) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-68017-8_44

Farrell, C., Kiel, J., Anatomy & Back Rhomboid Muscles. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), (2023).

Chow, D. H. K., Leung, K. T. Y. & Holmes, A. D. Changes in spinal curvature and proprioception of schoolboys carrying different weights of backpack. Ergonomics 50, 2148–2156 (2007).

Drzał-Grabiec, J., Snela, S., Rachwał, M., Rykała, J. & Podgórska, J. Effects of carrying a backpack in a symmetrical manner on the shape of the feet. Ergonomics 56, 1577–1583 (2013).

Carrying heavy school bags among Thai children. (2022). http://csip.org/ebook/no17/page5.html

Suvarnaho, S. & Ladavichitkul, P. Work load evaluation of the school bag carrying of primary students based on biomechanical approach. Eng. J. Res. Dev. 23, 48–53 (2012).

Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (L. Erlbaum Associates, 1988).

Deesungnern, S. & Thawinchai, N. A survey of factors associated with schoolbag carrying and pain during schoolbag usage in high school students of Darawittayalai School. Thai J. Phys. Ther. 36, 71–78 (2014).

CUergo Musculoskeletal Discomfort Questionnaires. https://ergo.human.cornell.edu/ahmsquest.html

Jansen, K. et al. Musculoskeletal discomfort in production assembly workers. Acta Kinesiol. Univ. Tartu. 18, 102–110 (2012).

Bandyopadhyay, S. et al. Quantification of Musculoskeletal Discomfort among Automobile Garage workers: a cross-sectional Analytical Study in Chetla, Kolkata, West Bengal. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2021/45296.14600 (2021).

Chheda, P. & Pol, T. Effect of sustained use of Smartphone on the Craniovertebral Angle and Hand Dexterity in Young adults. Int. J. Sci. Res. IJSR. 8, 1387–1390 (2019).

Wu, G. et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion–part II: shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. J. Biomech. 38, 981–992 (2005).

ISO 7250-1. 2017(en), Basic human body measurements for technological design — Part 1: Body measurement definitions and landmarks. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:7250:-1:ed-2:v1:en

ISO 11226:2000(en. ), Ergonomics — Evaluation of static working postures. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:11226:ed-1:v1:en

Akbar, F. et al. Prevalence of low Back pain among adolescents in relation to the weight of school bags. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 20, 37 (2019).

Assiri, A., Mahfouz, A. A., Awadalla, N. J., Abolyazid, A. Y. & Shalaby, M. Back Pain and Schoolbags among adolescents in Abha City, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 17, 5 (2020).

Chaudhari, M., Saini, S. K., Bharti, B., Gopinathan, N. R. & Narang, K. Heavy School bags and Musculoskeletal System problems among School-going children. Indian J. Pediatr. 88, 928–928 (2021).

P, P. C. et al. Effects of Upper Musculoskeletal disorder from School Bag usage among primary School Grade 4–6 students for a school in Bangkok Metropolis. J. Dep Med. Serv. 44, 48–53 (2019).

Chen, Y. L. & Mu, Y. C. Effects of backpack load and position on body strains in male schoolchildren while walking. PloS One. 13, e0193648 (2018).

Hardie, R., Haskew, R., Harris, J. & Hughes, G. The effects of Bag Style on muscle activity of the Trapezius, Erector Spinae and Latissimus Dorsi during walking in Female University students. J. Hum. Kinet. 45, 39–47 (2015).

Macias, B. R., Murthy, G., Chambers, H. & Hargens, A. R. High contact pressure beneath backpack straps of children contributes to Pain. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 159, 1186–1188 (2005).

Macias, B. R., Murthy, G., Chambers, H. & Hargens, A. R. Asymmetric loads and pain associated with backpack carrying by children. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 28, 512–517 (2008).

Mäkelä, J. P., Ramstad, R., Mattila, V. & Pihlajamäki, H. Brachial plexus lesions after backpack carriage in young adults. Clin. Orthop. 452, 205–209 (2006).

Micheli, L. J. & Fehlandt, A. F. Overuse injuries to tendons and apophyses in children and adolescents. Clin. Sports Med. 11, 713–726 (1992).

Vaghela, N. P., Parekh, S. K., Padsala, D. & Patel, D. Effect of backpack loading on cervical and sagittal shoulder posture in standing and after dynamic activity in school going children. J. Fam Med. Prim. Care. 8, 1076 (2019).

van Gessel, H., Gassmann, J. & Kröner-Herwig, B. Children in pain: recurrent back pain, abdominal pain, and headache in children and adolescents in a four-year-period. J. Pediatr. 158 (.e1–2), 977–983 (2011).

Shan, Z. et al. How schooling and lifestyle factors effect neck and shoulder pain? A cross-sectional survey of adolescents in China. Spine 39, E276–283 (2014).

Brzęk, A. et al. The weight of pupils’ schoolbags in early school age and its influence on body posture. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 18, 117 (2017).

Sankaran, S., John, J., Patra, S. S., Das, R. R. & Satapathy, A. K. Prevalence of Musculoskeletal Pain and its relation with weight of backpacks in School-going children in Eastern India. Front. Pain Res. 2, 684133 (2021).

Clinch, J. & Eccleston, C. Chronic musculoskeletal pain in children: assessment and management. Rheumatology 48, 466–474 (2009).

Spiteri, K. et al. Schoolbags and back pain in children between 8 and 13 years: a national study. Br. J. Pain. 11, 81–86 (2017).

Haselgrove, C. et al. Perceived school bag load, duration of carriage, and method of transport to school are associated with spinal pain in adolescents: an observational study. Aust J. Physiother. 54, 193–200 (2008).

Dianat, I., Sorkhi, N., Pourhossein, A., Alipour, A. & Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. Neck, shoulder and low back pain in secondary schoolchildren in relation to schoolbag carriage: should the recommended weight limits be gender-specific? Appl. Ergon. 45, 437–442 (2014).

Grimmer, K. & Williams, M. Gender-age environmental associates of adolescent low back pain. Appl. Ergon. 31, 343–360 (2000).

Siambanes, D., Martinez, J. W., Butler, E. W. & Haider, T. Influence of school backpacks on adolescent back pain. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 24, 211–217 (2004).

Mackenzie, W. G., Sampath, J. S., Kruse, R. W. & Sheir-Neiss, G. J. Backpacks in children. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1976–2007. 409, 78–84 (2003).

Whittfield, J. K., Legg, S. J. & Hedderley, D. I. The weight and use of schoolbags in New Zealand secondary schools. Ergonomics 44, 819–824 (2001).

Barbosa, J. et al. Schoolbag weight carriage in Portuguese children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study comparing possible influencing factors. BMC Pediatr. 19, 157 (2019).

Hell, A. K., Braunschweig, L., Grages, B., Brunner, R. & Romkes, J. Einfluss Des Schulrucksackgewichtes Bei Grundschulkindern: Gang, Muskelaktivität, Haltung Und Stabilität. Orthop 50, 446–454 (2021).

De Paula, A. J. F., Silva, J. C. P., Paschoarelli, L. C. & Fujii, J. B. Backpacks and school children’s obesity: challenges for public health and ergonomics. Work 41, 900–906 (2012).

Li, J. X., Hong, Y. & Robinson, P. D. The effect of load carriage on movement kinematics and respiratory parameters in children during walking. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 90, 35–43 (2003).

Dahl, K. D., Wang, H., Popp, J. K. & Dickin, D. C. Load distribution and postural changes in young adults when wearing a traditional backpack versus the BackTpack. Gait Posture. 45, 90–96 (2016).

Kistner, F., Fiebert, I., Roach, K. & Moore, J. Postural compensations and subjective complaints due to backpack loads and wear time in schoolchildren. Pediatr. Phys. Ther. Off Publ Sect. Pediatr. Am. Phys. Ther. Assoc. 25, 15–24 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all subjects who participated in the study. The authors would like to acknowledge the directors and teachers of all primary schools for their support throughout this study.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA) of Thailand and Walailak University Graduate Research Fund. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: J.M., U.N., C.R., C.P. Data collection: J.M. Data curation and formal analysis: J.M., U.N., C.R., C.P. Data interpretation: J.M., U.N., C.R., C.P. Resources: U.N., C.R., C.P. Manuscript drafting: J.M. Manuscript editing: U.N., C.R., C.P. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mongkonkansai, J., Narkkul, U., Rungruangbaiyok, C. et al. Exploring musculoskeletal discomfort and school bag loads among Thai primary school students: a school-based cross-sectional survey. Sci Rep 14, 30287 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81545-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81545-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating the performance of different machine learning algorithms based on SMOTE in predicting musculoskeletal disorders in elementary school students

BMC Medical Research Methodology (2025)