Abstract

Spodoptera litura (Fabricius) is a major polyphagous pest of global relevance due to the damage it causes to various crops. Chlorpyrifos (CPF) is generally used by farmers to manage S. litura, however, its widespread use has resulted in the development of insecticide resistance. Therefore, in the present study, a population of S. litura was exposed to CPF for eight generations under laboratory conditions, resulting in a 2.81-fold resistance ratio compared with that of the unselected laboratory population (Unsel-Lab). The exposure of Unsel-Lab and CPF-Sel populations to their respective lethal and sublethal concentrations reduced larval survival, adult emergence, and prolonged development period, and induced morphological deformities in adults. The reproductive and demographic parameters were also significantly lowered in the treated larvae of both populations at higher concentrations. Moreover, hormetic effects on fecundity, next-generation larvae, the net reproductive rate (R0), and relative fitness (Rf) were observed at lower sublethal concentrations of CPF, specifically at the LC5 of Unsel-Lab and the LC10 of the CPF-Sel population. Sublethal exposure to CPF negatively affected the biological and demographic parameters in both populations, although the impact was more prominent in the CPF-Sel population. The relative fitness of the CPF-Sel was also greatly reduced at the LC50 (0.28) compared to that of the Unsel-Lab population. However, only a marginal trade-off of insecticide resistance evolution was observed in the CPF-Sel population in the absence of insecticide selection pressure. These results provide useful information for devising improved pest management strategies for CPF resistance in S. litura.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spodoptera litura (Fabricius), (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), commonly known as tobacco cutworm, is a major polyphagous agricultural pest distributed in tropical and subtropical areas around the world infesting more than 300 plant species1,2,3. Management of S. litura is particularly challenging because adults can rapidly colonize new areas through long-distance flight, while their high fecundity allows populations to establish and multiply in invaded fields quickly4,5,6. The larvae of S. litura feed voraciously on leaves, stalks, flowers, and fruits of host plants and cause extensive damage to a variety of important crops including soybean, cotton, tobacco, cruciferous vegetables, and other important economic crops2,7. According to reports, S. litura is responsible for extensive economic damage and up to 100% yield losses in many crops8.

The most prevalent method used by farmers to maintain the S. litura population below the economic injury level is the use of synthetic insecticides, which are affordable, easy to use, and effective against the target pests9. Chlorpyrifos (CPF), an organophosphate (OP) insecticide, is one of the most commonly used broad-spectrum insecticides worldwide against a wide range of insect pests of agricultural importance including S. litura10,11. CPF can cause severe cholinergic poisoning in insects by suppressing the enzyme acetylcholinesterase (AChE) that hydrolyzes the neurotransmitter acetylcholine12,13. As a result, overstimulation of the nervous system leads to the insect death13. Despite its effectiveness, the frequent and unreasonable use of CPF has resulted in the evolution of resistance in S. litura9. Several studies have reported low to high levels of resistance to organophosphates including CPF in field populations of S. litura6,10,14,15.

In general, the development of resistance in pests is often linked with a decrease in the fitness of resistant individuals. The biological fitness of the resistant population measured in terms of insect survival, developmental period, fecundity and net reproductive rates often declined following continuous laboratory selection compared to that of its reference unselected population in the absence of pesticides16,17. The insecticide-resistant insects have higher energy costs and physiological disadvantages relative to susceptible insects which may be due to a trade-off in energy resource allocation18,19. Insecticide resistance-related fitness cost has been reported in numerous insect pests such as Spodoptera exigua (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) against tebufenozide20, Phenacoccus solenopsis (Tinsley) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) against deltamethrin21, Heliothis virescens (Fabricius) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) against indoxacarb and deltamethrin22, Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) against malathion23, and S. litura against imidacloprid24, profenofos25, and methoxyfenozide26. Insecticide resistance does not always entail fitness costs. Positive traits such as increased larval survival, egg hatchability, and increased fecundity or only marginal fitness costs can be observed in resistant insects under low doses or without insecticide exposure indicating a possible physiological mechanism of compensation27,28,29.

The selection for insecticide resistance is typically linked to the use of lethal concentrations of insecticides to eliminate susceptible individuals. However, sublethal concentrations also play a significant role in selecting resistant genotypes by favoring the survival and reproduction of resistant individuals30,31. “Sublethal effects” refers to the physiological and behavioral impacts on individuals or populations exposed to toxic substances at sublethal concentrations or doses32. In treated agroecosystems, insects are often exposed to lower or sublethal concentrations of insecticides, which can negatively affect insect development, growth, fecundity, and egg hatchability33,34,35. Interestingly, sublethal exposure to insecticides can also stimulate insect population growth or fecundity, leading to pest resurgence in the field36,37. This phenomenon is called hormesis, which includes both inhibitory and stimulatory effects depending on the dose and time of exposure to pesticides at sublethal dose rates38,39. Recently, various reports have been documented on the occurrence of hormesis in insect pests due to sublethal doses of insecticides. For instance, exposure to a low sublethal concentration of clothianidin increased the fecundity and net reproductive rate of fourth-instar larvae of Agrotis ipsilon (Hufnagel) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), while higher concentrations impaired the normal development and population parameters40. Similarly, the soybean aphid, Aphis glycines (Matsumura) treated with the lowest sublethal concentration (0.05 µg/mL ) of imidacloprid showed a significant increase in fecundity, whereas the higher concentration (0.20 µg/mL ) inhibited reproduction36. These studies underscore the complex nature of insect responses to insecticides and highlight the need for careful consideration of dosage in pest management strategies to minimize the risk of hormetic effects in target pests. Furthermore, it is critical to consider both the lethal or sublethal effects of an insecticide when estimating the total effect of any insecticide on insect pests for successful pest management35,39,41. Therefore, the current study was envisaged to assess the impact of CPF exposure on the key biological and demographic traits of S. litura. The present findings could help to gain a comprehensive understanding of the sublethal effects of CPF on S. litura over multigeneration exposure and to examine whether the population dynamics changed with time and differential susceptibility.

Results

Establishment of CPF selected population of S. Litura

There was a gradual increase in the LC50 values of CPF from the F1 (94.04 µg/mL) to F8 (232.79 µg/mL) generations in the CPF-Sel population, indicating a 2.81-fold increase in the LC50 when compared with the Unsel-Lab (82.84 µg/mL) population. The LC50 values for both populations were significantly different from each other as their 95% confidence intervals did not overlap, with p > 0.05. Furthermore, the χ2 goodness-of-fit tests were not significant for any of the assays indicating a good fit of probit models (Table 1).

Lethal and sublethal concentrations for Unsel-Lab and CPF-Sel populations

The concentration-response bioassays were conducted on second-instar larvae of S. litura. The lethal and sublethal concentrations, i.e., the LC50, LC30, LC20, LC10, and LC5, of CPF for the Unsel-Lab population were determined to be 82.84, 44.89, 30.98, 18.53, and 12.12 µg/mL while those for the CPF-Sel population were 232.79, 125.62, 86.50, 51.55, and 33.62 µg/mL, respectively. When compared with one another, all the sublethal values were significantly different from each other as there was no overlap of the fiducial limits between the same treatments of both populations (Table 2).

Larval survival and development time

The percent larval survival showed significant differences among concentrations (F(5,48) = 98.52**, p < 0.01), however, no significant effect was observed between Unsel-Lab and CPF- Sel populations and for the interaction of concentration and population (Table 3). The maximum decrease of 52.17% in larval survival was observed in the Unsel-Lab population at the LC50 concentration relative to that of the control. The larval development time indicated significant differences among concentrations (F(5,48) = 668.52**, p < 0.01), between populations (F(1,48) = 550.22**, p < 0.01), and for concentration-population interaction (F(5,48) = 79.08**, p < 0.01). The interaction effect here signifies that the larval period was affected differently across concentrations for each population. For the pupal development period, significant differences were observed only between concentrations (F(5,48) = 45.46**, p < 0.01) and populations (F(1,48) = 35.34**, p < 0.01). The concentration-population interaction remained unaffected for the pupal period. On the other hand, the development time from egg to adult emergence (DT) showed significant variations among concentrations (F(5,48) = 431.96**, p < 0.01) and between populations (F(1,48) = 411.43**, p < 0.01). The concentration-population interaction was also found to be significant suggesting that the impact of concentrations varies between the two populations (F(5,48) = 53.42**, p < 0.01). The generation time (DT) was considerably longer in the CPF-Sel population than in the Unsel-Lab population (Table 3). A significant reduction in adult emergence was also observed among concentrations in treated larvae within the populations (F(5,48) = 28.17**, p < 0.01). However, differences between populations and concentration-population interactions were not significant (Table 4). Similar results were observed for morphological deformities in adults of both populations where the CPF-Sel population showed deformities in 36.66% of adults, while it was 26.66% in the Unsel-Lab population at LC50 value (F(5,48) = 19.12**, p < 0.01) (Table 4).

Reproductive potential

According to the two-way analysis of variance (Univariate GLM), no interaction was observed for male and female longevity of S. litura adults. However, a significant decrease in longevity of both males (F(5,24) = 7.02**, p < 0.01) and females (F(5,24) = 21.29**, p < 0.01) was observed among concentrations of both populations. The results indicated a decreasing trend in the number of eggs laid per female at the higher concentrations, however, at lower concentrations both the populations showed increased fecundity compared to that of the control group (F(5,24) = 210.96**, p < 0.01). Furthermore, a significant concentration-population interaction was observed for fecundity (F(5,24) = 37.27**, p < 0.01). In contrast, the concentration population interaction for egg hatching (%) remained unaffected. Nonetheless, egg hatching (%) declined significantly at higher concentrations within both populations with a maximum reduction of 39.08% at LC50 for the CPF-Sel population relative to its control (F(5,24) = 191.24**, p < 0.01). The egg hatching (%) was also affected significantly between the populations (F(1,24) = 45.22**, p < 0.01). A significant interaction between the S. litura population and concentration (F(5,24) = 38.71**, p < 0.01) was also detected for expected next-generation larvae. The main effects of population (F(1,24) = 26.79**, p < 0.01) and concentration (F(5,24) = 481.92**, p < 0.01) on this variable were also significant (Table 5).

Demographic parameters

The population growth parameters obtained from the biological and reproductive parameters of the Unsel-Lab and CPF-Sel populations fed on untreated (control group) and treated castor leaves with different concentrations of CPF showed significant differences for all the parameters. The net reproductive rate (R0) indicated significant differences for concentration (F(5,24) = 481.92**, p < 0.01), population (F(1,24) = 26.79**, p < 0.01), and their interaction (F(5,24) = 38.71**, p < 0.01). Among treatments within the population, the R0 was highest at LC5 followed by the control group for the Unsel-Lab population. The LC50 of the CPF-Sel population resulted in the lowest R0 value, showing a decrease of 30.44% compared to the R0 of Unsel-Lab at the LC50 value (Table 6).

The intrinsic rate of population increase (r) was significantly different for concentration (F(5,24) = 1544.10**, p < 0.01), population (F(1,24) = 535.09**, p < 0.01), and their interaction (F (5,24) = 70.33**, p < 0.01). Compared to the control group, 35.29% decrease in r values was observed in the LC50 treated Unsel-Lab population. The CPF-Sel population showed a minimum r value at the highest concentration, i.e., LC50 indicating 17.27% decrease as compared to the LC50 of the Unsel-Lab population. The main effects of concentration (F (5,24) = 1556.88**, p < 0.01), population (F(1,24) = 531.62**, p < 0.01), and their interaction (F (5,24) = 67.70**, p < 0.01) on the finite rate of population increase (λ) also differed significantly. However, the maximum decrease was observed in the LC50 treatment of the CPF-Sel population indicating a 7.28% reduction compared to the control of the Unsel-Lab population (Table 6).

Relative fitness (Rf) was calculated by taking the R0 of the control group of the Unsel-Lab population as a reference. The Rf was found to be considerably increased in lower doses of both populations particularly at the LC5 of Unsel-Lab, and LC10 of the CPF-Sel population. A reduction in Rf was observed in treated larvae at higher concentrations with maximum effect at LC50 of the CPF-Sel population where the Rf value was 0.28 compared to the control group (Fig. 1).

Discussion

Chemical insecticides are still considered an important strategy for controlling insect pests in agroecosystems, but their frequent use poses a threat of selection pressure and causes resistance problems in insect pests17,42. The insecticide selection pressure is often associated with the use of lethal concentrations that possibly eliminate susceptible individuals30. However, insect pests are often exposed to varying levels of sublethal insecticide doses in fields as the insecticide concentration gradually declines due to rainwater leaching and degradation in the field43,44. Therefore, understanding the sublethal effects of an insecticide on the biological traits of its target pest is critical for the rational use of insecticides and for developing effective IPM programs31,45. As CPF is a widely used insecticide against S. litura, it is important to study the sublethal effects of this insecticide on S. litura.

The results indicated that the selection pressure of CPF induced a low level of resistance in S. litura from the F1 to F8 generations. An increase in the LC50 of CPF from 94.04 µg/mL in F1 to 232 µg/mL in the CPF-Sel (F8) population indicated 2.81-fold increase in resistance ratio compared to the Unsel-Lab (F8) population. A low-level resistance was also reported by Zhang et al.10 where the resistant ratio of S. litura larvae to CPF was increased to 3.47-fold over the susceptible strain after being treated for 12 generations. Besides lepidopterans, insecticide-induced low level of resisitance has also been documented in insect pests belonging to different orders. For instance, resistance of Aphis gossypii (Glover) (Hemiptera: Aphididae) to imidacloprid displayed a slow increase with a resistance ratio of 4.81-fold for selection pressure upto 9 generations46. Similarly, in yellow fever Mosquito, Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus) (Diptera: Culicidae), continued selections for 40 generations caused only a 3.80-fold increase in tolerance to deltamethrin47. Furthermore, Liriomyza sativae (Blanchard) showed a moderate level of resistance to CPF, with a resistance ratio of 40.34-fold after 23 generations of continuous laboratory selection compared to an unselected population48. In contrast, P. solenopsis exhibited a higher level of resistance, with a resistance ratio of 539.76-fold after 9 generations of continuous laboratory selection49. This suggests that the resistance levels associated with the selection process under laboratory conditions can be low, moderate, or high depending on a variety of factors such as the number of generations involved in the selection process, previous history of exposure to insecticides, selection techniques, and geographic origins of populations and presence of susceptible and resistant genes15,50.

The lethal/sublethal concentrations of insecticides can adversely affect various biological parameters of insects51,52,53. In the present study, the larval survival rate was significantly reduced in the treated larvae than in the control larvae. We also observed a significant prolongation in the development time from egg to adult emergence in both populations compared to the respective control groups, while these effects were more prominent in the CPF-Sel population. This finding is in line with the widely recognized concept that the evolution of resistance entails an adaptation cost during the selection process, which can prolong the development period in resistant individuals54. Resistant insects often experience greater energy expenses and physiological constraints compared to their susceptible counterparts, due to a trade-off in the allocation of energy resources16,55. The sublethal concentrations of insecticides can decrease larval survival and prolong larval development in various insect pests. For instance, the sublethal concentrations of chlorantraniliprole, dinotefuran, and beta-cypermethrin reduced the survival rates and prolonged the larval development of Spodoptera frugiperda (JE Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)56. Our findings are also in line with previous studies indicating a prolonged larval period and pupal period when S. litura larvae were treated with higher sublethal concentrations of methoxyfenozide26. In the present study, adult emergence of S. litura was also negatively influenced after treatment with sublethal concentrations of CPF. Similar alterations, such as delayed development and reduced adult emergence have earlier been reported in Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and Plutella xylostella (Linnaeus) (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) following treatment with sublethal concentrations of spinosad and spinetoram, respectively57,58. In addition, both populations observed a significant increase in the proportion of deformed adults at sublethal doses of CPF. Similar results have previously been documented in Helicoverpa assulta (Guenée) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), P. xylostella, and A. ipsilon due to sublethal effects of cyantraniliprole, fluxametamide, and chlorantraniliprole, respectively51,53,59. The present study also indicated reduced male and female longevity, fecundity, and percent egg hatching in the Unsel-Lab and CPF-Sel populations at higher lethal concentrations. Our finding of reduced adult longevity, lower fecundity, and egg hatching (%) corroborates the findings of studies conducted by Rehan and Freed26 where they observed a considerable impact of methoxyfenozide on parental generation of S. litura. The shorter longevity of males and females may result in reduced fecundity leading to a decline in resistant populations over time60.

The demographic parameters reflect the overall influence of the insecticide on the population of an insect. Sublethal concentrations of an insecticide have a significant impact on the population projection of insect pests including S. litura26,53,59. In the current investigation, the mean values of R0, r, and λ in both populations were significantly reduced at higher concentrations than in the control groups. We also observed lower Rf in treated larvae of S. litura, notably at LC50 of the CPF-Sel population of S. litura. Such alterations may take place when insects are exposed to sublethal concentrations of insecticide to maximize their survival and these changes are likely to vary among insect populations of the same species, particularly when they differ in insecticide susceptibility29,53,61. In our study, the trade-off of biological fitness in the evolution of insecticide resistance resulted only in prolonged development time, reduced adult emergence, and percent egg hatching, upon removal of insecticide selection pressure suggesting marginal or no fitness costs in resistant individuals. The studies conducted by Feng et al.29 showed that the effects of imidacloprid resistance on the life history traits of Paederus fuscipes Curtis (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) were limited, and only a prolonged egg incubation period and decreased adult longevity were detected as imidacloprid resistance increased. Moreover, a strong hormetic effect and skewed sex ratio were observed upon sublethal exposure to Paederus beetles29.

The exposure to potentially fatal extrinsic factors may boost reproduction efforts to sustain progeny. This phenomenon is called hormesis which is a rather prevalent event in arthropods under insecticidal stress. Insecticide hormesis includes both high-dose inhibitory and low-dose stimulatory effects. It is a dose and time-dependent phenomenon in which impacts are demonstrated as a result of exposure to pesticide sublethal dose rate38,39. Our results also revealed an increased fecundity, expected next-generation larvae, and R0 at lower concentrations in each population (LC5 of Unsel-Lab and LC10 of CPF-Sel) suggesting the stimulatory effects of lower doses and reduction at higher concentrations in each population. The observed trend of increased Rf at lower doses, specifically the LC5 of Unsel-Lab and the LC10 of the CPF-Sel population, also followed a similar trend. Previously, the increased fecundity at lower doses has also been documented in various insect pests across multiple generations38,39. The results of the current investigations are also in line with the studies conducted by Raen et al.62 on transgenerational effects of triazophos in two Pectinophora gossypiella (Saunders) generations (F0 and F1) for high-dose inhibition (reduced fecundity) and low-dose stimulation (longer oviposition period).

The endpoint of sublethal effects mainly depends on the insecticide dose, pest populations, and insect species63. In the present study, significant interactions describe the effect of the combination of two factors (concentration of CPF and population type) on the measured variables such as development period, fecundity, egg hatching percentage, expected next-generation larvae, and demographic parameters. The presence of a significant interaction indicates that the effect of one factor is dependent on the level of the other factor. In other words, the populations react differently to varying doses of insecticides, and the effect of lethal/ sublethal concentration on the observed variables is not the same for both populations61. For instance, the significant concentration-population interactions for R0, r, and λ indicate that CPF-Sel and Unsel-Lab populations respond differently to increasing concentration levels. CPF-Sel showed a more pronounced decline in all three parameters as concentration increased, with sharper drops in R0, r, and λ at higher concentrations compared to the Unsel-Lab population. This differential response may reflect varying tolerance mechanisms or adaptive responses to the concentrations applied. Consequently, it is crucial to take the interaction effect into account when analyzing the overall effects of CPF exposure on S. litura. While our findings provide an important insight into biological as well as demographic parameters, further research on underlying mechanisms and long-term effects is crucial. Having a thorough understanding of these dynamics helps decision-makers to develop pest management techniques that are both environmentally friendly and successful.

Materials and methods

Insect culture

The egg masses and larvae of S. litura were collected from the infested fields around Amritsar (Punjab), India (31.643805° N and 74.822690° E). This initial field-collected population was designated as F0 which was reared on fresh castor leaves in plastic jars (15 cm × 10 cm) in an insect culture room under controlled temperature, humidity, and photoperiod conditions of 25 ± 2 oC and 65 ± 5% and 14:10 h (L: D), respectively. The leaves were changed daily till pupation and the pupae were then transferred to the pupation jars containing moist sand till the emergence of adults. On emergence, the adults (2 females: 1 male ratio) were transferred to oviposition jars (15 cm × 10 cm) containing 2–3 cm moist sand and lined with filter paper to facilitate egg laying. The adults were given a 20% honey solution, soaked on a cotton ball hanging from the muslin cloth covering the jar. After 2–3 days of emergence, these adults laid eggs on filter paper which were transferred to the Petri dishes for hatching. The newly hatched larvae were then transferred to rearing jars (15 cm × 10 cm) containing fresh castor leaves64. These newly hatched larvae (neonates) were then designated as the F1 generation.

Insecticide used

The commercial formulation of chlorpyrifos 20% EC (chemical name: O, O-diethyl-O-3,5,6-trichlor-2-pyridyl phosphorothioate; Crop Chemical India Limited, New Delhi) was selected based on its use for the control of S. litura as recommended by the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare and Central Insecticide Board and Registration Committee, Government of India65. All the experiments were conducted with fresh solutions of CPF prepared in distilled water to avoid insecticide decomposition.

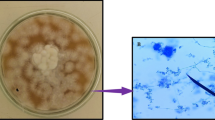

Establishment of CPF selected population of S. Litura

The selection of S. litura with CPF was done as per the protocol of Ishtiaq et al.66 and Cheema et al.67 with slight modifications (Fig. 2). The same environmental conditions as described for insect culture were maintained in the laboratory for the selection of S. litura with CPF. This F1 generation obtained from F0 generation was then divided into two sub-populations, in which, one population was fed solely on normal untreated castor leaves for up to eight generations and was designated as the Unsel-Lab population. The other population exposed to CPF-treated castor leaves up to the 8th generation was designated as the CPF-Sel population. For selection up to the 8th generation, the 2nd instar larvae of the F1 generation were exposed to a range of concentrations (5–320 µg/mL) of CPF, and mortality was recorded after 48 h to determine the LC50. The individuals surviving from the treated population at concentrations ≥ LC50 (94.04 µg/mL) were collected and reared on fresh castor leaves to obtain a batch of the selected generation that was designated as F2. The larvae from the F2 generation were exposed to the LC50 concentration of 94.04 µg/mL (LC50 of F1) and the individuals surviving at ≥ LC50 were reared to obtain F3. The 2nd instar larvae of F3 were treated with a range of 20–1280 µg/mL of CPF to calculate the LC50 for that generation and individuals surviving at ≥ LC50 were reared further. The LC50 value obtained for F3 was then used to select two subsequent generations F4 and F5. A similar procedure was followed for the F6 and the LC50 value calculated was subsequently used for the selection of the next generation (F7). Finally, the LC50 values were calculated for the F8 generation, designated as the CPF-selected population (CPF-Sel) (Fig. 2).

Toxicity bioassay

The concentration-response bioassay was performed on newly hatched 2nd instar larvae from the 8th generation of the Unsel-Lab (F8) and CPF-Sel (F8) population of S. litura using castor leaf discs (10 cm2). For each bioassay, a range of concentrations of CPF were freshly prepared using distilled water along with control. The concentrations used for the Unsel-Lab population were 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 200, 250, and 320 µg/mL, and the concentrations used for the CPF-Sel population were 10, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, and 1280 µg/mL. Fresh castor leaves were dipped in different concentrations of the insecticide for 10–15 s and air dried at room temperature for 30–40 min. The air-dried insecticide-treated leaves were fed to the pre-starved 2nd instar larvae while the control group was fed on the leaves washed in distilled water only. The bioassays were conducted using 50 larvae for each concentration, along with a control group. There were 5 replicates per concentration, with 10 larvae in each replicate. The concentration-response bioassays were carried out in the laboratory under the same environmental conditions as described in the insect culture section. Mortality was recorded after 48 h exposure period to insecticide and the larvae that did not respond after being stimulated by a fine-haired brush were recognized as dead. The LC50 and the other sublethal(LC5, LC10, LC20, and LC30) concentrations at 48 h were estimated from the obtained data by using probit analysis.

Biological and demographic growth parameters

To evaluate the effect of low/sub (LC5, LC10, LC20, and LC30), and median lethal LC50 concentrations on the biological and demographic parameters of S. litura, the 2nd instar larvae were fed upon the leaves treated with the concentrations of CPF equivalent to LC5, LC10, LC20, LC30, and LC50 estimated for the Unsel-Lab (F8) and CPF-Sel (F8) populations. The larvae that were fed solely on untreated castor leaves were used as control groups. The experiments were conducted under controlled temperature, humidity, and photoperiod conditions of 25 ± 2oC and 65 ± 5% and 14:10 h (L: D), respectively. The larvae were fed on castor leaves exposed to different concentrations of CPF every alternate day till pupation and the observations were made daily on various biological parameters such as larval period, pupal period, development period from the egg to adult emergence (DT), adult emergence, and adult deformities. The experiment was conducted using 50 larvae with 5 replications for each concentration along with control group. The newly emerged healthy adult females and males were paired (2 females: 1 male)64 in an oviposition jar with moistened cotton containing 20% sugar solution and were kept under constant temperature, humidity, and photoperiod conditions as described above. For each treatment, the experiment was replicated thrice. The cotton plugs in each oviposition jar were changed every day during the spawning period. The reproductive parameters, including male and female longevity, fecundity, and egg hatching (%) were checked daily. The number of eggs was thoroughly checked and recorded daily. The egg batches were transferred to Petri dishes for hatching and neonates were counted daily. The data were then analyzed to assess various demographic parameters of different treatments for each population. The percentage of egg hatching was calculated by using the following formula given by Liu and Han68 as under:

The number of eggs a female produces throughout her lifetime was used to calculate fecundity while the net reproductive rate (R0) was estimated as per Cao and Han69:

where Nn represents the number of the parent generation, while Nn + 1 refers to the neonates of the next generation.`.

Using the value of the net reproductive rate (R0), the intrinsic rate of population growth (r) was calculated by using the method described by Birch70, Alyokhin and Ferro71, and Ijaz and Shad72:

where DT is the period of development from the egg to adult emergence (Ijaz and Shad72).

The finite rate of population increase (λ) i.e., the factor whereby a population multiplies in 1 day was calculated as per Qu et al.36:

According to Cao and Han69, relative fitness was assessed as follows:

Relative fitness (Rf) = R0 of tested population or treatment ÷ R0 of the control group of Unsel-Lab population.

Statistical analysis

The mortality data recorded after 48 h of treatment were used to calculate median lethal (LC50), and sublethal (LC5, LC10, LC20, and LC30) concentrations using probit analysis (IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software) with 95% confidence intervals, χ2 values with degrees of freedom (df), slope, and their standard errors. The LC50 values were considered similar if the 95% confidence intervals of both bioassays overlapped73. The resistance ratio (RR) for each selected generation was calculated compared to the laboratory-susceptible population74. Two-way univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s test at p < 0.05 was carried out to determine the effects of different concentrations of CPF on Unsel-Lab and CPF-Sel populations. All the data points were represented as the Mean ± Standard Error (SE). The statistical analysis has been carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Corp.) and Microsoft Office Professional Plus 2021 (Microsoft Corporation).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study showed the potential of S. litura to develop resistance against CPF upon repetitive selection pressure. Moreover, the lethal and sublethal exposure of CPF and its resistance against S. litura can cause varying effects on development, survival, and reproduction that might result in inflicting a significant impact on the demographic parameters of S. litura. Further investigation on biochemical and molecular characteristics is very necessary to better understand the mechanism by which CPF affects the various biological parameters of S. litura. As we cannot completely ban insecticides due to ever increasing demand of food for the growing world population, therefore, to mitigate the problem of insecticide resistance, rotation of insecticides in fields and the use of alternative strategies such as the use of bio-control agents should be implemented in the integrated pest management. Therefore, our results can serve as the basis for developing rational insecticide resistance management strategies.

Data availability

Data sets used or analyzed in the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Tuan, S. J., Li, N. J., Yeh, C. C., Tang, L. C. & Chi, H. Effects of green manure cover crops on Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) populations. J. Econ. Entomol. 107, 897–905 (2014).

Bragard, C. et al. Pest categorisation of Spodoptera litura. EFSA J. 17, e05765 (2019).

Yinghua, S., Yan, D., Jin, C., Jiaxi, W. & Jianwu, W. Responses of the cutworm Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to two Bt corn hybrids expressing Cry1Ab. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–13 (2017).

Tojo, S. et al. Overseas migration of the common cutworm, Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), from May to Mid-july in East Asia. Appl. Entomol. Zool. 48, 131–140 (2013).

Armes, N. J., Wightman, J. A., Jadhav, D. R. & Rao, G. V. R. Status of insecticide resistance in Spodoptera litura in Andhra Pradesh, India. Pestic Sci. 50(3), 240–248 (1997).

Huang, Q., Wang, X., Yao, X., Gong, C. & Shen, L. Effects of bistrifluron resistance on the biological traits of Spodoptera litura (Fab.) (Noctuidae: Lepidoptera). Ecotoxicology 28, 323–332 (2019).

Ganguly, S. & Srivastava, C. P. Comparative biology of Spodoptera litura Fabricius on different food sources under controlled conditions. J. Exp. Zool. India. 23(1), 681–684 (2020).

Dhir, B., Mohapatra, H. & Senapati, B. Assessment of crop loss in groundnut due to tobacco caterpillar, Spodoptera litura (F). Indian J. Plant. Prot. 20, 215–217 (1992).

Saraswathi, S. et al. Overview of pest status, control strategies for Spodoptera litura (Fab.): a review. J. Biopest 16(2) (2023).

Zhang, N. et al. Expression profiles of glutathione S-transferase superfamily in Spodoptera litura tolerated to sublethal doses of chlorpyrifos. Insect Sci. 23, 675–687 (2016).

Teng, H., Zuo, Y., Jin, Z., Wu, Y. & Yang, Y. Associations between acetylcholinesterase-1 mutations and chlorpyrifos resistance in beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 184, 105105 (2022).

Krishnaswamy, V. G. et al. Effect of chlorpyrifos on the earthworm Eudrilus euginae and their gut microbiome by toxicological and metagenomic analysis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 37, (2021).

Dewer, Y. et al. Behavioral and metabolic effects of sublethal doses of two insecticides, chlorpyrifos and methomyl, in the Egyptian cotton leafworm, Spodoptera littoralis (Boisduval) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 23, 3086–3096 (2016).

Shad, S. A. et al. Field evolved resistance to carbamates, organophosphates, pyrethroids, and new chemistry insecticides in Spodoptera litura Fab. (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Pest Sci. 85, 153–162 (2012).

Xu, L. et al. SlGSTE8 in Spodoptera litura participated in the resistance to phoxim and chlorpyrifos. J. Appl. Entomol. 147, 809–818 (2023).

Banazeer, A., Ali, S., Babar, M. & Afzal, S. Laboratory induced bifenthrin resistance selection in Oxycarenus Hyalinipennis (Costa) (Hemiptera: Lygaeidae): Stability, cross-resistance, dominance and effects on biological fitness. Crop Prot. 132, (2020).

Khan, M. A. et al. Experimental parasitology unstable fipronil resistance associated with fitness costs in fipronil-selected. Exp. Parasitol. 250, 108543 (2023).

Amaral Rocha, É. A., Silva, R. M., da Silva, R., Cruz, B. K., Fernandes, F. L. & C. G. & Fitness cost and reversion of resistance leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae) to chlorpyrifos. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 242, 113831 (2022).

Kliot, A. & Ghanim, M. Fitness costs associated with insecticide resistance. Pest Manag Sci. 68(11), 1431–1437 (2012).

Jia, B. et al. Inheritance, fitness cost and mechanism of resistance to tebufenozide in Spodoptera exigua (Hübner) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pest Manag Sci. 65, 996–1002 (2009).

Saddiq, B., Shahzad Afzal, M. B. & Shad, S. A. Studies on genetics, stability and possible mechanism of deltamethrin resistance in Phenacoccus Solenopsis Tinsley (Homoptera: Pseudococcidae) from Pakistan. J. Genet. 95, 1009–1016 (2016).

Sayyed, A. H., Ahmad, M. & Crickmore, N. Fitness costs limit the development of resistance to Indoxacarb and Deltamethrin in Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 101, 1927–1933 (2008).

Arnaud, L. & Haubruge, E. Insecticide resistance enhances male reproductive success in a beetle. Evol. (N Y). 56, 2435–2444 (2002).

Abbas, N., Shad, S. A. & Razaq, M. Fitness cost, cross resistance and realized heritability of resistance to imidacloprid in Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 103, 181–188 (2012).

Abbas, N. et al. Resistance of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to profenofos: relative fitness and cross resistance. Crop Prot. 58, 49–54 (2014).

Rehan, A. & Freed, S. Fitness cost of methoxyfenozide and the effects of its sublethal doses on development, reproduction, and survival of Spodoptera litura (Fabricius) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 44, 513–520 (2015).

Yin, X. H., Wu, Q. J., Li, X. F., Zhang, Y. J. & Xu, B. Y. Demographic changes in multigeneration Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) after exposure to sublethal concentrations of spinosad. J. Econ. Entomol. 102, 357–365 (2009).

Ribeiro, L. M. S., Wanderley-Teixeira, V., Ferreira, H. N., Teixeira, Á. A. C. & Siqueira, H. A. A. Fitness costs associated with field-evolved resistance to chlorantraniliprole in Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 104, 88–96 (2014).

Feng, W., Bin, Bong, L. J., Dai, S. M. & Neoh, K. B. Effect of imidacloprid exposure on life history traits in the agricultural generalist predator Paederus beetle: lack of fitness cost but strong hormetic effect and skewed sex ratio. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 174, 390–400 (2019).

Guedes, R. N. C., Walse, S. S. & Throne, J. E. Sublethal exposure, insecticide resistance, and community stress. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 21, 47–53 (2017).

D’Ávila, V. A. et al. Lambda-cyhalothrin exposure, mating behavior and reproductive output of pyrethroid-susceptible and resistant lady beetles (Eriopis connexa). Crop Prot. 107, 41–47 (2018).

Desneux, N., Decourtye, A. & Delpuech, J. M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 52, 81–106 (2007).

Yuan, H. et al. Lethal, sublethal and transgenerational effects of the novel chiral neonicotinoid pesticide cycloxaprid on demographic and behavioral traits of Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Insect Sci. 24, 743–752 (2017).

Ali, E. et al. Sublethal effects of buprofezin on development and reproduction in the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). Sci. Rep. 2017 71 7, 1–9 (2017).

Shi, Y. et al. Sublethal effects of nitenpyram on the biological traits and metabolic enzymes of the white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera (Hemiptera: Delphacidae). Crop Prot. 155, 105931 (2022).

Qu, Y. et al. Sublethal and hormesis effects of imidacloprid on the soybean aphid Aphis glycines. Ecotoxicology 24, 479–487 (2015).

Cordeiro, E. M. G., de Moura, I. L. T., Fadini, M. A. M. & Guedes, R. N. C. Beyond selectivity: Are behavioral avoidance and hormesis likely causes of pyrethroid-induced outbreaks of the southern red mite Oligonychus ilicis? Chemosphere 93, 1111–1116 (2013).

Sial, M. U. et al. Evaluation of insecticides induced hormesis on the demographic parameters of Myzus persicae and expression changes of metabolic resistance detoxification genes. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–8 (2018).

Basana Gowda, G. et al. Insecticide-induced hormesis in a factitious host, Corcyra Cephalonica, stimulates the development of its gregarious ecto-parasitoid, Habrobracon hebetor. Biol. Control. 160, 104680 (2021).

Ding, J., Zhao, Y., Zhang, Z., Xu, C. & Mu, W. Sublethal and Hormesis effects of Clothianidin on the Black Cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 111, 2809–2816 (2018).

Afza, R., Asam, M., Afzal, M. & Majeed, M. Z. Adverse effect of sublethal concentrations of insecticides on the Biological parameters and functional response of Predatory Beetle Coccinella septempunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) of Brassica Aphid. Sarhad J. Agric. 37, 226–234 (2021).

Akhtar, Z. R. et al. Lethal, Sub-lethal and trans-generational effects of chlorantraniliprole on biological parameters, demographic traits, and fitness costs of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Insects 13, (2022).

Zhu, G. et al. Biological and physiological responses of two Bradysia pests, Bradysia odoriphaga and Bradysia difformis, to Dinotefuran and Lufenuron. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 190, 105338 (2023).

Ullah, F. et al. Thiamethoxam induces transgenerational hormesis effects and alteration of genes expression in Aphis gossypii. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 165, 104557 (2020).

Garlet, C. G. et al. Fitness cost of chlorpyrifos resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) on different host plants. Environ. Entomol. 50, 898–908 (2021).

Shi, X. et al. Toxicities and sublethal effects of seven neonicotinoid insecticides on survival, growth and reproduction of imidacloprid-resistant cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag Sci. 67, 1528–1533 (2011).

Kumar, S. et al. Effect of the synergist, piperonyl butoxide, on the development of deltamethrin resistance in yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti L. (Diptera: Culicidae). Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 50, 1–8 (2002).

Askari-Saryazdi, G., Hejazi, M. J., Ferguson, J. S. & Rashidi, M. R. Selection for chlorpyrifos resistance in Liriomyza sativae Blanchard: cross-resistance patterns, stability and biochemical mechanisms. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 124, 86–92 (2015).

Ejaz, M. et al. Laboratory selection of chlorpyrifos resistance in an invasive pest, Phenacoccus solenopsis (Homoptera: Pseudococcidae): cross-resistance, stability and fitness cost. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 137, 8–14 (2017).

Malik, S. J., Freed, S., Ali, N., Ismail, H. M. & Naeem, A. Nitenpyram selection, resistance and biochemical characterization in dusky cotton bug, Oxycarenus Hyalinipennis Costa (Hemiptera: Lygaeidae). Crop Prot. 125, 104904 (2019).

Dong, J., Wang, K., Li, Y. & Wang, S. Lethal and sublethal effects of cyantraniliprole on Helicoverpa assulta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 136, 58–63 (2017).

Sedaratian, A., Fathipour, Y., Talaei-Hassanloui, R. & Jurat-Fuentes, J. L. Fitness costs of sublethal exposure to Bacillus thuringiensis in Helicoverpa armigera: a carryover study on offspring. J. Appl. Entomol. 137, 540–549 (2013).

Gope, A. et al. Toxicity and sublethal effects of fluxametamide on the key biological parameters and life history traits of diamondback moth Plutella xylostella (L). Agronomy 12, 1–16 (2022).

Barbosa, M. G. et al. Insecticide rotation and adaptive fitness cost underlying insecticide resistance management for Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 49, 882–892 (2020).

Khalid, I., Kamran, M., Abubakar, M., Khizar, M. & Shad, S. A. Effect of autosomally inherited, incompletely dominant, and unstable spinosad resistance on physiology of Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): realized heritability and cross-resistance. J. Stored Prod. Res. 100, 102069 (2023).

Wu, H. M. et al. Sublethal effects of three insecticides on development and reproduction of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Agron. 12, 1334 (2022).

Wang, D., Gong, P., Li, M., Qiu, X. & Wang, K. Sublethal effects of spinosad on survival, growth and reproduction of Helicoverpa armigera (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pest Manag Sci. 65(2), 223–227 (2009).

Tamilselvan, R., Kennedy, J. S. & Suganthi, A. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of spinetoram on the biological traits of Plutella xylostella (L.) (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). Ecotoxicology 30, 667–677 (2021).

He, F. et al. Chlorantraniliprole against the black cutworm Agrotis ipsilon (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae): from biochemical/physiological to demographic responses. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–17 (2019).

Hafeez, M. et al. Sub-lethal effects of lufenuron exposure on spotted bollworm Earias Vittella (Fab): key biological traits and detoxification enzymes activity. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 14300–14312. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04655-8 (2019).

Von Veloso, S., Pereira, R., Guedes, E. J. G., Oliveira, M. G. & R. N. C. & A. does cypermethrin affect enzyme activity, respiration rate and walking behavior of the maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais)? Insect Sci. 20, 358–366 (2013).

Raen, Z. et al. Triazophos induced lethal, sub-lethal and transgenerational effects on biological parameters and demographic traits of Pectinophora gossypiella using two sex life table. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 34, 102319 (2022).

Yin, X. H., Wu, Q. J., Li, X. F., Zhang, Y. J. & Xu, B. Y. Sublethal effects of spinosad on Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Yponomeutidae). Crop Prot. 27, 1385–1391 (2008).

Thakur, A., Dhammi, P., Saini, H. S. & Kaur, S. Pathogenicity of bacteria isolated from gut of Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and fitness costs of insect associated with consumption of bacteria. J. Invertebr Pathol. 127, 38–46 (2015).

Central Insecticides Board and Registration Committee Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare. Government of India. http://cibrc.nic.in (2020).

Ishtiaq, M. et al. Stability, cross-resistance and fitness costs of resistance to emamectin benzoate in a re-selected field population of the beet armyworm, Spodoptera exigua (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Crop Prot. 65, 227–231 (2014).

Cheema, H. K., Kang, B. K., Jindal, V., Kaur, S. & Gupta, V. K. Biochemical mechanisms and molecular analysis of fenvalerate resistant population of Spodoptera litura (Fabricius). Crop Prot. 127, 104951 (2020).

Liu, Z. & Han, Z. Fitness costs of laboratory-selected imidacloprid resistance in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens Stål. Pest Manag Sci. 62, 279–282 (2006).

Cao, G. & Han, Z. Tebufenozide resistance selected in Plutella xylostella and its cross-resistance and fitness cost. Pest Manag Sci. 62, 746–751 (2006).

Birch, L. C. The intrinsic rate of natural increase of an insect population. J. Anim. Ecol. 17, 15 (1948).

Alyokhin, A. V. & Ferro, D. N. Relative fitness of Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) resistant and susceptible to the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry3A toxin. J. Econ. Entomol. 92, 510–515 (1999).

Ijaz, M. & Shad, S. A. Stability and fitness cost associated with spirotetramat resistance in Oxycarenus Hyalinipennis Costa (Hemiptera: Lygaeidae). Pest Manag Sci. 78(2), 572–578 (2022).

Litchfield, J. J. & Wilcoxon, F. A simplified method of evaluating dose-effect experiments. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 96, (1949).

Robertson, J. & Preisler, H. Pesticide bioassays with arthropods. CRC, Boca Raton, FL. J. Econ. Entomol. 88(5), 1513–1516 (1992).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Zoology, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar (Punjab), India for providing infrastructural facilities. The financial assistance received from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India (File no. 09/254(0285)2018-EMR-I) is gratefully acknowledged by Meena Devi. Arushi Mahajan acknowledges the Department of Science and Technology/INSPIRE fellowship New Delhi (India) for the financial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K. and H.S.S. contributed to conceptualization, supervision and validation. M.D. contributed to the investigation, conceptualization, writing - original draft, data curation, and data analysis. S.S. and A.M. provided assistance and visualization. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies involving humans/animals/plants that need approval from an ethical committee.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Devi, M., Sarkhandia, S., Mahajan, A. et al. Fitness costs associated with laboratory induced resistance to chlorpyrifos in Spodoptera litura. Sci Rep 14, 30874 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81739-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81739-7