Abstract

This study investigated the relationships among exposure to risky online content, moral disengagement, media literacy, and cyberaggression in adolescents (aged 13–15 years). Data were obtained from the 2021 Cyber Violence Survey (N = 3,002) conducted by a national agency in the Republic of Korea using systematic stratified sampling. The survey assessed eight aggressive online behaviors as indicators of cyberaggression: verbal violence, defamation, stalking, sending provocative content, personal information leakage, bullying, extortion, and coercion. Additionally, media literacy was assessed using two components relevant to the online environment: trust testing and privacy management, and intimacy sharing with strangers. The findings revealed a positive association between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement among adolescents, which was mitigated by higher levels of media literacy, particularly regarding intimacy sharing (e.g., disagreeing with exchanging photos or information with strangers or sharing passwords with friends). Moral disengagement related to cyberaggression increased the likelihood of aggressive behavior online. Furthermore, media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing) reduced both cyberaggression and moral disengagement. Our findings imply that providing media literacy along with tackling moral disengagement would counter cyberaggression effectively. Future research could consider the longitudinal impact of media literacy on cyberaggression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cyberaggression, or aggressive online behavior, is a serious global problem. It is defined as “intentional harm delivered by electronic means to a person or group, irrespective of age, who perceive(s) such acts as offensive, derogatory, harmful, or unwanted” (p. 152)1. The term encompasses cyberbullying, harassment, stalking, sexting, abuse, and other violent behaviors conducted via mobile phones or the Internet2,3. In the United States, 46% of adolescents aged 13–17 years report encountering at least one form of aggressive online behavior, such as offensive name-calling, receiving unsolicited explicit images, and spreading false rumors4. Approximately 41% of Korean adolescents also experience cyberaggression, with approximately 25% reporting experiences as perpetrators5; instant messaging and social network services were the main channels on which they encountered cyberaggression. A European Union report emphasizes the social and psychological costs of cyberaggression, noting that some adolescent perpetrators psychologically distance themselves by dismissing it as stupid drama6. Another report from Korea explains that some adolescent perpetrators may perceive online aggression as mere play7. This phenomenon suggests moral disengagement concerning cyberaggression.

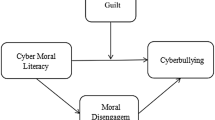

This study addresses three questions regarding moral disengagement related to cyberaggression among adolescents. In particular, it focuses on the associations of moral disengagement and three potentially related variables: exposure to risky online content, cyberaggression, and media literacy. The first question is, “Is risky online content exposure associated with adolescents’ moral disengagement?” This study empirically investigates the association between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement among adolescents. Previous research explains risky online content as depicting immoral behavior (e.g., violent and cruel behavior, provocative sexual behavior, offensive language directed at celebrities, illegal behavior, and spreading disinformation)8. Media provide cues about acceptable behavior or speech by portraying social norms9. Therefore, risky online content exposure may be associated with adolescents’ cognitive interpretation that immoral behavior is acceptable. However, few studies have examined the link between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement among adolescents.

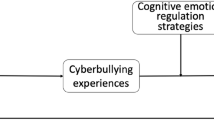

Our second question is, “Does moral disengagement lead adolescents to report perpetration of cyberaggression?” This question focuses on the link between moral disengagement and cyberaggression behavior reported by adolescents as perpetrators. Moral disengagement may be associated with immoral behavior10,11,12,13; however, their relationship has some unclear aspects. For instance, some studies have examined the effects of traditional moral disengagement (e.g., “It is alright to fight to protect your friends”) on immoral online behavior such as cyberbullying10,12. Another confirmed that general moral disengagement regarding online behavior (e.g., “It is right to share someone’s intimate images to highlight a problem”) relates to cyberbullying among adolescents13,14. The present study focuses on moral disengagement that specifically reflects cyberaggression to better understand this association. We examine the relationships between moral disengagement and actual reports of eight types of aggressive online behavior: verbal violence, defamation, stalking, sending provocative content, personal information leakage, bullying, extortion, and coercion.

We propose the final question, “How does media literacy relate to online moral disengagement and cyberaggression in adolescents?” Media literacy has various dimensions and a broad scope. Notably, it can predict outcomes relevant not only to media but also to behavior15. For instance, media literacy helps mitigate risky behavior, as adolescents with higher media literacy may better adjust their immediate responses to harmful media messages16. This study addresses a research gap by analyzing the role of media literacy in the relationship between risky online content exposure, moral disengagement, and cyberaggression. Furthermore, it focuses on two components of media literacy that are applicable to the online environment: trust testing and privacy management, and intimacy sharing with strangers17,18. This study provides empirical evidence for the role of media literacy in the context of risky online content exposure, moral disengagement, and cyberaggression.

Literature review

Risky online content exposure and moral disengagement

In his social cognitive theory, Bandura describes humans as emergent agents who interpret and evaluate behavior using a cognitive process9,19. People possess the cognitive ability to regulate and control their actions, often consciously deciding on a specific behavior to achieve the intended results19. Furthermore, people reconstruct their thoughts regarding certain behavior to adapt to changing situations, assess behavior based on functional values, and evaluate the appropriateness of their thoughts by considering the effects of their actions. Internal standards for behavior serve as a self-sanctioning baseline that promotes humane conduct and dissuades inhumane behavior19,20. However, individual internal standards may not always align with broader moral standards because the cognitive interpretation of behavioral adequacy is influenced by social interactions21. For instance, aggressive children may judge coercive behavior as aligning with their standards if they believe that it will help them achieve their goals22. In this context, the individual acts as a moral agent who self-selects and performs a behavior even when it goes against moral standards23. Bandura suggested that immoral behavior is a result of selectively disengaging from self-sanctions grounded in moral standards23.

Moral disengagement refers to the cognitive detachment of immoral behavior from moral standards24,25. Bandura et al. considered cognitive construal as the key to moral disengagement24. People refrain from behaving in ways that violate their moral standards because such behaviors bring self-censure24,26. However, people can escape self-censure and potential guilt when they cognitively justify their immoral behavior. Thus, moral disengagement could increase the likelihood of immoral acts by disinhibiting immoral behavior27. Moral disengagement has eight mechanisms—moral justification, euphemistic labeling, advantageous comparison, displacement of responsibility, diffusion of responsibility, distorting or minimizing consequences, attribution of blame, and dehumanization—that each lead to the perception that immoral behavior is normal or even unproblematic24,27. A key aspect of moral disengagement is the cognitive reconstruction of immoral behavior24, which occurs when immoral behavior is rationalized or justified10.

Cognitive constructions or evaluations of actions are products of the interplay among three determinants: individuals, their behavior, and the environment9,19,21. Mass media’s influential role in social interplay is tied to its symbolizing and vicarious capabilities. Humans have an advanced capacity for observational learning, and the range of observational models expands vastly in a symbolic environment9. Furthermore, people gain symbolic information from vicarious experiences related to behavior, the environment, and society, and transform these symbols into cognitive models that reflect their internal standards of behavior21. As shown by the “Bobo doll” experiments, adolescents acquire information about aggressive behavior that is socially acceptable by observing media portrayals28. This insight forms the basis of research on media violence and antisocial behavior. Specifically, media depictions of aggressive behavior or speech may cue adolescents regarding the social acceptability of certain aggressive behaviors29.

This claim has been tested in the context of media violence, particularly the association between video games and moral disengagement in children and adolescents29,30,31,32,33. Recent research on media violence and violent communication has also focused on video games wherein adolescents may encounter depictions of immoral behavior34. However, it is essential to consider depictions of immoral behavior as content rather than focusing solely on video games. The core mechanism behind cognitive distortions—wherein immoral behavior is perceived as acceptable or unproblematic—lies in media portrayals that may contribute to justifying such behavior or internalizing harmful scripts35. For instance, Richmond and Wilson found that music with lyrics featuring immoral themes, such as violence, sexual promiscuity, and perversion, could increase moral disengagement35. In this vein, violent video games glorify immoral behavior, including assault, robbery, and rape32. Thus, violent video game exposure could be related to moral disengagement regarding behaviors such as cheating, aggression, and other harmful actions36.

Moreover, immoral behavior depicted in the media may not always align with morally disengaged immoral behavior. For instance, experience with sexting could be associated with cyberbullying, either as a perpetrator or a victim37,38. These studies suggest that violent sexting, as an extension of cyberaggression, could serve as practice for other immoral behaviors. Advantageous comparisons, as one of the mechanisms of moral disengagement, provide helpful insights into this association by allowing individuals to perceive their behavior as acceptable or less problematic by comparing it to more harmful acts39. The association between exposure to violent media and moral disengagement might be relevant to this mechanism in the context of cyberaggression, which could be seen as a minor issue compared to the more extreme behaviors depicted in media14. Risky online content includes the portrayal of immoral behaviors such as violent and cruel actions, provocative sexual behavior, offensive language directed at celebrities, illegal behavior, and the spread of disinformation8. Spreading disinformation, such as fake news or false rumors, is considered a type of cyberaggression25. However, the association between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement in relation to cyberaggression is yet to be determined. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1

Exposure to risky online content is positively associated with moral disengagement among adolescents.

Moral disengagement and cyberaggression

Online interactions can be a playground for moral disengagement regarding cyberaggression because it is a social setting enabled by electronic communication11,12,14. Runions and Bak proposed a conceptual framework to explain some of the features and functions of online environments that can facilitate moral disengagement14. For example, adolescents may find it more challenging to recognize social-emotional cues online than in face-to-face communication. Disinhibition from moral behavioral standards may occur more readily in online interactions because it is difficult to immediately gauge another’s response to behavior or speech40.

Two important aspects should be considered when investigating the effects of moral disengagement on cyberaggression. First, moral disengagement, which traditionally focuses on aggressive behavior in face-to-face interactions, may also relate to cyberaggression as an extension of real-world aggression. Two systematic studies have linked moral disengagement in face-to-face interactions and cyberaggression in adolescents10,12. For instance, Lo Cricchio et al. reported that moral disengagement increased involvement in cyberaggression among children and adolescents12. Gini et al. found that moral disengagement increased different types of aggressive behavior (i.e., general aggression, bullying, and cyberbullying), with a similar effect size for each type10. Another study found moral disengagement to be positively associated with online hate speech among adolescents41. These studies support that general moral disengagement related to various immoral behaviors11,13,42.

Second, some studies distinguish moral disengagement in an online environment from that in face-to-face interactions13,14. Moral disengagement should reflect the specific environment and behavior it aims to explain13. For instance, it may contribute to immoral online behavior among adolescents when it directly reflects the online environment or behaviors. Paciello et al. confirmed that online and traditional moral disengagement are distinct, with moral disengagement related to online behavior having a greater impact on cyberaggression perpetration than traditional measures of moral disengagement13. In line with this, Bussey et al. adjusted the items in traditional measures to reflect moral disengagement in cyberaggression43. They operationalize moral disengagement as agreement with statements such as, “It is alright to send a mean message using a mobile phone or the Internet to someone if they have poked fun at your friends.” Several studies have since adopted this measure, with some revealing a positive association between online moral disengagement and cyberaggression44,45,46,47.

As discussed earlier, the association between risky online content exposure and moral disengagement may not always align with the same type of immoral behavior. However, previous studies indicate that the association between cognitive distortion and actual immoral behavior may be much more apparent when moral disengagement reflects the specific context13,43,44. To further explore this point, we recall the earlier part of our literature review, which highlighted the internal evaluation of specific behaviors that could permit actual immoral behavior19,20,21,22. Various cues, including media depictions of violence, can be associated with individual moral standards for specific online behavior. However, moral disengagement could relate to actual immoral behavior when it reflects the specific immoral behavior (e.g., cyberaggression) or the environment (e.g., online). To examine the association between moral disengagement and actual cyberaggression among adolescents, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

Moral disengagement regarding cyberaggression is positively associated with cyberaggression among adolescents.

The role of media literacy

A consensus is yet to be reached on the definition of media literacy that encompasses various dimensions. Aufderheide defined media literacy as the “ability of a citizen to access, analyze, and produce information for specific outcomes” (p. 6)48. Livingstone expands this to various media, defining media literacy as “the ability to access, analyze, evaluate and create messages across a variety of contexts” (p. 18)49. Jeong et al. describe the common components of media literacy as specific knowledge or skills that enable critical understanding and media use15. However, media literacy is constantly evolving alongside changes in media, communication, and technology50. Thus, Hobbs defines media literacy as “the everchanging set of knowledge, skills, and habits of mind required for full participation in a contemporary media-saturated society (p. 4)50.” This includes addressing the risks associated with media and digital technology, competent media use, and the assessment of message credibility and quality51. Therefore, media literacy enables individuals to assess the credibility of information, safeguard themselves and others online, and respond effectively to risky or harmful content52.

Media literacy outcomes have been classified as media- or behavior-relevant15. Media-relevant outcomes refer to media-relevant knowledge or skills, including media construction, persuasive goals of media messaging, and media criticism and influence. Furthermore, media literacy can be associated with behavior-relevant outcomes, such as individual beliefs, attitudes, norms, and behaviors. Each outcome is relevant to the message interpretation process (MIP) model that explains the effects of media messages on individuals’ decision-making processes53. In the MIP model, which is based on Bandura’s social cognitive theory, media messaging are cues for logical comparisons and affects recipients’ expectations or decisions regarding their behavior54. Notably, recipients logically assesses whether the media message is realistic or correct before internalizing it. Additionally, the recipient assesses the anticipated outcomes of imitating the behaviors depicted in the media messages. Austin et al. demonstrated empirical evidence of media literacy’s effects on perceived realism and adolescent behavior expectations55. For instance, adolescents with a greater desire to smoke rated smoking ads as less realistic after participating in media literacy programs. Moreover, adolescents who participated in media literacy programs had lower expectations regarding the benefits of smoking.

Austin and Domgaard’s work provides insight into the association between media literacy and individual behavior change56. Media literacy is related to logic-oriented responses to content, rather than emotional responses to message sources57. Austin and Domgaard noted that critical thinking about message content is associated with evidence-based beliefs, whereas affect-based beliefs are associated less with critical thinking56. That is, individuals with higher media literacy assess message content logically, while individuals with lower media literacy respond emotionally based on simple affinity for the messages or sources. Therefore, media literacy guides decision-making55 and may support adolescents in developing skills to make better choices when they are exposed to risky online content or considering risky behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and engaging in sexual activity promoted by media messages58. Adolescents with greater media literacy can control their automatic responses to content by thoroughly understanding the effects of risky online content and immoral behaviors16. In line with this perspective, we can expect adolescents with greater media literacy to evaluate cyberaggression negatively despite regular exposure to risky online content.

This study focuses on the conflict between moral disengagement and media literacy that occurs within the relationship between moral disengagement and cyberaggression in adolescents. In other words, it examines the role of media literacy as a moderator in the association between moral disengagement and actual cyberaggression among adolescents. Moral disengagement could relate to actual cyberaggression because it reflects individual standards regarding the acceptability of cyberaggression. However, adolescents with higher media literacy have more information about appropriate online behaviors. Therefore, we can expect adolescents with higher media literacy to engage in appropriate online behaviors based on relevant knowledge or beliefs.

There is no standard approach for assessing media literacy because it encompasses diverse purposes, technologies, definitions, and contexts59. However, Livingstone suggests that media literacy can be applied to specific tasks suited to the characteristics of the online environment and adolescents’ development17. Trust testing, privacy management, and intimacy sharing are mentioned as specific tasks relevant to media literacy in online environments17,18. These tasks include verifying the accuracy of messages, interpreting cues exchanged during asynchronous online communication, and appropriately managing privacy when interacting with strangers online. This study uses these two components of media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, and intimacy sharing) as moderators to examine their relation to the association of moral disengagement and cyberbullying in adolescents. Thus, we pose the following research questions:

-

RQ1a. Does media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing) moderate the relationship between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement among adolescents?

-

RQ1b. Does media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing) moderate the relationship between moral disengagement on cyberaggression and actual cyberaggression among adolescents?

Method

Data and participants

This study obtained data from the 2021 Cyber Violence Survey, an open-access public dataset in the Republic of Korea with new data collected annually by the National Information Society Agency (NIA) since 2013. Previous studies using this data have investigated exposure to risky online content, cyber offending, cyberaggression, and perceptions of cyberaggression among adolescents8,60. From September to November 2021, survey participants were recruited through systematic and stratified sampling based on the 2020 Statistical Yearbook of Education. Participants included 3,002 Korean adolescents (50.6% female) aged 13–15 years (M = 14.00, SD = 0.80) who responded to all the main variables in this study.

Ethical approval was not required because this study used an open-access public dataset without personal identifiers. Furthermore, participants were able to skip any questions in the self-reported survey if they did not want to respond to them. NIA, the primary source, released this dataset and permitted its use as secondary data61. The permission regulations of the NIA were adhered to in this study.

Measures

Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were performed to verify the internal validity of the scales constructed. We first applied exploratory factor analysis for risky online content exposure, moral disengagement, and media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing) to half of our data. Three variables and two media literacy components were confirmed using SPSS 29.0 (KMO = 0.91, p < .001). Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 26.0 was applied to the second half of the data, confirming internal validity with an acceptable model fit (TLI = 0.94, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.058), and all regression weights exceeded 0.50.

Exposure to risky online content

This study measured exposure to risky online content using five items from the 2021 Cyber Violence Survey. A previous study confirmed the internal validity of these five items8. The first item asked, “Have you ever seen the contents below online? [the violent and cruel contents].” The other four items were regarding cursing or speaking badly about celebrities or public figures, provocative sexual content (including sexual body parts or behavior), illegal behavior (including cheating or thievery), and spreading disinformation (intentionally presenting false information as facts). Participants rated the five items on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“none”) to 6 (“almost every day”). The measure demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90).

Moral disengagement regarding cyberaggression

A previous study measured moral disengagement as the extent to which participants perceived specific behaviors as unproblematic (e.g., “It is all right to send a mean message using a mobile phone or the Internet to someone if they have poked fun at your friends.”)42. This method was employed to examine the following eight aggressive online behaviors: verbal violence, defamation, stalking, sending provocative content, personal information leakage, bullying, extortion, and coercion8. Each aggressive online behavior was represented as an item following an introductory question, for instance “How problematic are the following online behaviors?” was followed by “[using swear words or hurting other people’s feelings (for verbal violence)],” “[Repeated posting of text/photos or sending e-mails/messages online without the agreement or permission of the other party, who is opposed to such behavior (for stalking)].” Participants rated the eight behaviors on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all a problem”) to 4 (“very problematic”). These items were reverse coded such that higher scores indicated higher levels of moral disengagement. The measure demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95).

Media literacy

While there is no standard approach for measuring media literacy, researchers have applied self-assessments of behavior that are relevant to the competencies of media literacy59. The 2021 Cyber Violence Survey measured media literacy by focusing on trust testing, privacy management, and intimacy sharing. These concepts were adopted from previous studies17,18. A sample item is “I first check the source or author to judge the truth of the information.” Other items asked about checking information before judgment, judging the authenticity of others’ profiles, using privacy management options, accepting requests from others to exchange photos or phone numbers, and sharing passwords on SNS websites or via email. Participants rated these nine items on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”). Higher scores indicate higher media literacy levels. Three items were reverse coded (e.g., “I accept friend requests from strangers online”).

The present study confirmed two components of media literacy. The first component was trust testing and privacy management (six items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83): “I first check the source or author to judge the truth of the information”; “I check again using other search engines or apps to judge the truth of the information”; “I know how to judge the authenticity of others’ profiles online”; “I have not activated the function for open access to my location information on smartphone apps such as Facebook”; “I use reporting functions when others violate my rights online”; and “I set privacy options differently according to the characteristics of the personal information.” The second component was intimacy sharing (three items, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85): “I have accepted requests for offline meetings, exchanged contact numbers, and exchanged photos with a stranger online” (reverse coded); “I share passwords for SNS websites or email with my friends” (reverse coded); and “I accept friend requests from strangers online” (reverse coded).

Cyberaggression

Cyberaggression was measured by the actual perpetration experience of the same eight behaviors used for moral disengagement. A previous study confirmed the internal validity of these eight items8. Participants responded to the eight items measuring their experiences of perpetration over the last year. A sample item is, “In the past year, have you ever engaged in the following behavior using the Internet or a smartphone? [using swear words or hurting other people’s feelings (for verbal violence)]” Participants rated items on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“none”), 1 (“once or twice in one year”), 2(“once or twice in half year”), 3(“once or twice in one month”), 4(“once or twice in one week”) to 5 (“almost every day”). Cyberaggression was not normally distributed in our data. Furthermore, the current study was interested in whether the participants engaged in cyberaggression as perpetrators. Therefore, we recorded responses as a binary variable (1 = “have experience” for response options 1–5 and 0 = “no experience” for response option 0) for analysis.

Control variables

The research model controlled for sex and Internet usage time. The 2021 Cyber Violence Survey measured Internet usage time per day with a single item utilizing a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“less than an hour”) to 6 (“more than five hours”). Sex was coded as a binary variable (0 = male; 1 = female).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 29.0. We confirmed that no data were missing in the main variables and demographic information. Descriptive statistics were used for general demographic data, with frequency and percentage (n, %) applied to count data and mean ± standard deviation used for measurement data. Pearson correlations were employed to confirm the correlations among the main variables. This study used hierarchical multiple regression and logistic regression analyses to examine our hypotheses and research questions. Moreover, PROCESS macro model 2 was used to investigate the conditional effects of moderators62.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlational analysis

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations of the major variables. Approximately 14.9% of participants (n = 448) responded that they had engaged in one or more instances of cyberaggression in the past year. In contrast, 85.1% of participants (n = 2,554) responded that they had not engaged in any type of cyberaggression.

Risky online content exposure was positively correlated with moral disengagement (r = .15, p < .001). Furthermore, a negative association was identified between risky online content exposure and media literacy (trust testing and privacy management: r = − .23, p < .001; intimacy sharing: r = − .08, p < .001). Moral disengagement regarding cyberaggression was negatively correlated with media literacy (trust testing and privacy management: r = − .15, p < .001; intimacy sharing: r = − .19, p < .001). Interestingly, there also was a negative association between the two components of media literacy (r = − .26, p < .001).

Exposure to risky online content, moral disengagement, and the moderating role of media literacy

H1 hypothesized that risky online content exposure is positively associated with moral disengagement among adolescents. Furthermore, RQ1a suggested that media literacy moderates the relationship between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis tested H1 and RQ1a, treating exposure to risky online content as the independent variable, moral disengagement as the dependent variable, and media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing) as the moderators. Results indicated that exposure to risky online content increased moral disengagement (β = 0.145, p < .001), supporting H1 (Model 1 in Table 2).

Regarding RQ1a, media literacy was associated negatively with moral disengagement (trust testing and privacy management: β = − 0.189, p < .001; intimacy sharing: β = − 0.228, p < .001), as shown in Model 2 in Table 2. Moderation analysis must consider the possibility that the moderator is another independent variable significantly associated with a dependent variable63,64,65. The two components of media literacy were other explanatory variables negatively associated with moral disengagement in Model 2 and 3. Furthermore, the interaction effect between exposure to risky online content and media literacy (intimacy sharing) in Model 3 was significant (β = − 0.183, p < .01). This indicates that intimacy sharing, as a component of media literacy, mitigated the positive association between risky online content exposure and moral disengagement.

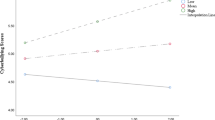

Conditional effects of intimacy sharing were analyzed using PROCESS macro model 2. Risky online content exposure increased moral disengagement when intimacy sharing was at mid (M) or low levels (M-1SD). However, the positive association between risky online content exposure and moral disengagement was insignificant when intimacy sharing was high (M + 1SD). This result was consistent, regardless of the levels of trust testing and privacy management among participants. Figure 1 illustrates the conditional effects of intimacy sharing as a moderator between risky online content exposure and moral disengagement.

Conditional effects of media literacy (intimacy sharing) between risky online content exposure and the moral disengagement on cyberaggression. Note This figure depicts the interaction effects between risky online content exposure and media literacy (intimacy sharing) on moral disengagement concerning cyberaggression when media literacy (trust testing and privacy management) is at a medium level. The conditional effects analysis showed that risky online content exposure was insignificant when media literacy (intimacy sharing) was high regardless of media literacy (trust testing and privacy management) level.

Moral disengagement, cyberaggression, and the moderating role of media literacy

H2 hypothesized a positive association between moral disengagement regarding cyberaggression and actual cyberaggression. Furthermore, RQ1b suggested a moderating role of media literacy in the relationship between moral disengagement and cyberaggression. Hierarchical logistic regression with forward selection was used to test H2 and RQ1b66. As shown in Table 3, Model 1 did not have an acceptable fit according to the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. However, Model 2 showed that moral disengagement was significantly associated with cyberaggression when accounting for media literacy levels (OR = 1.336, 95% CI [1.114–1.603], p = .002). In Model 2, the Nagelkerke R-square value was 0.036, and the classification accuracy of the logistic regression model was 85.1%. These results partially support H2.

Regarding RQ1b, as Model 2 in Table 3 shows, media literacy was associated negatively with cyberaggression (trust testing and privacy management: OR = 0.617, 95% CI [0.513–0.742], p < .001; intimacy sharing: OR = 0.775, 95% CI [0.681–0.882], p < .001). Notably, media literacy was also negatively associated with cyberaggression in Model 3, which considers the main effect of moral disengagement and the interaction effects (trust testing and privacy management: OR = 0.533, 95% CI [0.333–0.852], p < .001; intimacy sharing: OR = 0.627, 95% CI [0.447–0.879], p < .001). However, the interaction effects of moral disengagement and media literacy were not significant (Model 3 in Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the relationship between exposure to risky online content, moral disengagement, and cyberaggression among adolescents. Additionally, it investigated the role of media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing) in these relationships. The findings revealed that adolescents with greater exposure to risky online content were more likely to view cyberaggression as unproblematic. This finding aligns with previous research on social cognitive theory and moral disengagement28,29, suggesting that adolescents may interpret media depictions as cues for the social acceptability of cyberaggression. This also supports the view that depictions of immoral behavior in the media can contribute to moral disengagement with respect to other immoral behaviors14,35. Specifically, exposure to risky online content depicting immoral behavior (i.e., cursing, provocative sexual content, illegal behavior, and spreading disinformation) may foster cognitive distortions that minimize the perceived seriousness of cyberaggression. This study addresses an existing research gap by providing empirical evidence linking exposure to risky online content with moral disengagement in cyberaggression among adolescents.

Furthermore, moral disengagement increased aggressive online behavior among adolescents. This finding supports prior studies that have reported an association between moral disengagement and expressed cyberaggression10,12. Additionally, it confirms the relationship between moral disengagement and cyberaggression across eight immoral behaviors (verbal violence, stalking, defamation, sending provocative content, personal information leakage, bullying, extortion, and coercion). However, this finding must be interpreted carefully because our model was insignificant when considering moral disengagement only, but significant when including media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing). In other words, moral disengagement alone may not comprehensively explain cyberaggression among adolescents. Our findings illustrate that the association between moral disengagement and actual cyberaggression could be better explained by considering other factors relevant to cyberaggression (e.g., media literacy). Nevertheless, this study confirmed an association between moral disengagement and cyberaggression among adolescents.

This study also confirmed the two roles of media literacy in moral disengagement and cyberaggression among adolescents. First, it mitigates the positive relationship between risky online content exposure and moral disengagement. As mentioned earlier, risky online content exposure could be associated with the cognitive distortion that cyberaggression is acceptable. However, this association was found to be weakened in adolescents with higher levels of media literacy related to intimacy sharing. Media literacy supports better choices regarding media messages and online behavior by helping people understand what is appropriate16,55,58. In line with this perspective, this finding affirms that media literacy related to intimacy sharing mitigates the relationship between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement. In other words, adolescents may interpret cyberaggression as inappropriate, even if they are exposed to risky online content when they possess a high level of media literacy relevant to intimacy sharing. This finding supports the MIP model that individuals can assess media messages logically or based on evidence when they have higher media literacy levels53,54. This contributes to a more elaborate understanding of the role of media literacy in the relationship between risky online content exposure and moral disengagement on cyberaggression.

By contrast, we did not find moderating effects of trust testing and privacy management on the association between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement. We revisit the perspective that the cognitive evaluation of behavior is likely to be associated with actual behavior when it reflects specific contexts or detailed actions. In this study, intimacy sharing is concerned with online interaction with others, such as strangers or friends, while trust testing and privacy management focus on solitary activities, such as fact-checking or disabling location services. These two components were evaluated as the main aspects of media literacy needed in an online environment17,18. However, knowledge regarding intimacy sharing, which focuses on interaction with others, might fit more as a counter to cyberaggression than that regarding trust testing and privacy management because cyberaggression is also one way of interacting with others. A previous study found a need for consistency between the subdomains of media literacy and individual behavior67. For instance, as shown in Jones-Jang et al.67, only competencies related to information identification in media literacy could increase the likelihood of identifying fake news stories, while competency related to perceived familiarity with Internet-related terms could not. Thus, our findings corroborate that media literacy related to online interactions with others is needed to counter the association between risky online content exposure and moral disengagement with cyberaggression.

Another role of media literacy is in decreasing moral disengagement and cyberaggression among adolescents. Our findings show that media literacy (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing) is negatively associated with moral disengagement and cyberaggression. Media literacy can be associated with beliefs, norms, and attitudes toward behaviors15. Thus, a previous study highlighted encouraging behaviors (e.g., restricting accessibility or traceability, social privacy management, and checking sources for information) as media literacy intervention strategies68. The present study revealed that adolescents with high media literacy levels for trust testing, privacy management, and intimacy sharing negatively assessed cyberaggression and engaged less in actual aggressive behavior. Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory can be used to interpret this finding69. According to this theory, people experience psychological discomfort when they face conflicting beliefs or behaviors. Cyberaggression conflicts with media literacy in terms of moral standards. Thus, adolescents with higher media literacy may evaluate cyberaggression negatively because moral disengagement concerning cyberaggression triggers cognitive inconsistencies in their moral standards for behavior. Moreover, adolescents with higher media literacy might not permit or adopt actual aggressive online behavior that is cognitively inconsistent with their standards because they recognize appropriate online behavior. Therefore, media literacy reduces antisocial15, unhealthy58, and immoral online behaviors16. Thus, this study provides valuable empirical evidence that media literacy can help decrease both moral disengagement and cyberaggression among adolescents.

Our findings provide important implications for future research and practice. First, both moral disengagement and media literacy should be considered in countering cyberaggression in adolescents. Interventions that aim only to restrict cyberaggression may not be sufficiently motivating, because the purpose seems too obvious to adolescents. Furthermore, adolescents may need guidelines for appropriate online behavior to replace cyberaggression. Decreasing moral disengagement may not be associated with reduced cyberaggression if adolescents cannot learn appropriate online behaviors. Behavior based on media literacy may be an ideal standard for appropriate decision-making in online environments. Second, exposure to risky online content should be minimized to decrease moral disengagement. The cognitive construction of individual behavior is produced through social interactions. Thus, moral disengagement may be reinforced when adolescents are frequently exposed to risky online content. Media literacy interventions may provide strategies for adolescents to critically analyze and avoid such content. If they understand appropriate online behavior, adolescents can assess and avoid the harmful effects of risky online content instead of becoming absorbed in it.

Despite its contributions, this study has some limitations. First, causal conclusions cannot be drawn because this study used cross-sectional data. Future research could examine the causal relationships among exposure to risky online content, moral disengagement, and cyberaggression using a longitudinal approach. For instance, are adolescents with higher levels of moral disengagement more likely to seek risky online content? However, moral disengagement may be reinforced when adolescents consume risky online content or when they achieve their goals by (or are not punished after) engaging in cyberaggression. Thus, longitudinal studies that assess these variables may shed light on the causal directions of these relationships.

Second, this study measured only a few specific behaviors relevant to media literacy. However, this limitation highlights the need for future research to investigate the effects of media literacy more actively based on our findings. What are the common effects of media literacy on adolescent cyberaggression? How do these effects differ across the components of media literacy? What components moderate or mediate cyberaggression among adolescents? While this research focused on two components (trust testing and privacy management, intimacy sharing), future studies may consider other components or measures of media literacy to investigate its effects more comprehensively.

Finally, only adolescents aged 13–15 years participated in this study. Future research should consider the possibility of different effects across the various stages of adolescence. Moreover, social environments may affect adolescents’ moral disengagement and cyberaggression. Therefore, studies should compare the effects of peer norms, classroom norms, and exposure to risky online content. Participants may also have presented an idealized version of themselves in the self-report survey. Future research could reduce social desirability bias by incorporating a combination of methods, including self-reports, teacher or expert evaluations, and vignette-based assessments.

Conclusion

This study enhances our understanding of the role of moral disengagement and media literacy in the relationship between risky online content exposure and cyberaggression among adolescents. Importantly, our findings indicate that the relationship between exposure to risky online content and moral disengagement is weaker in adolescents with higher levels of media literacy. Additionally, moral disengagement related to cyberaggression was found to interact with media literacy among adolescents. An important question for future research is how adolescents can be encouraged to engage in media literacy-related behaviors, rather than in cyberaggression, through their cognitive interpretations.

Data availability

The public data without identifiers that support the findings of this study are available from the National Information Society Agency in Korea, here: https://www.data.go.kr/data/15106136/fileData.do. Data, including only the main variables of this study, are available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from the National Information Society Agency in Korea. Requests can be directed to the first or corresponding author beginning three months and ending three years after publication.

References

Grigg, D. W. Cyber-aggression: Definition and concept of cyberbullying. J. Psychol. Couns. Schools. 20 (2), 143–156 (2010).

Jagayat, A. & Choma, B. L. Cyber-aggression towards women: Measurement and psychological predictors in gaming communities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 120, 106753 (2021).

Willard, N. E. Cyberbullying and Cyberthreats: Responding to the Challenge of Online Social Aggression, Threats, and Distress (Research, 2007).

Pew Research Center & Teens and Cyberbullying Pew Research Center, 2022. (2022). https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2022/12/15/teens-and-cyberbullying-2022/ (Accessed: 22 Aug 2024).

Korea Communications Commission. The Report for 2022 Cyber Violence Survey. Korea Communications Commission,. (2023). https://www.iitp.kr/kr/1/knowledge/statisticsView.it?masterCode=publication&searClassCode=K_STAT_01&identifier=02-008-230324-000003 (Accessed: 1 Nov 2024).

European Union. Cyberbullying Among Young People. European Union,. (2016). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/571367/IPOL_STU(2016)571367_EN.pdf (Accessed: 22 Aug 2024).

Korea Communications Commission. The Report for 2023 Cyber Violence Survey. Korea Communications Commission,. (2024). https://kcc.go.kr/user.do?boardId=1113&page=A05030000&dc=K00000200&boardSeq=60294&mode=view (Accessed: 9 Aug 2024).

Bae, S. M. The relationship between exposure to risky online content, cyber victimization, perception of cyberbullying, and cyberbullying offending in Korean adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 123, 105946 (2021).

Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory (Prentice Hall, Inc., 1986).

Gini, G., Pozzoli, T. & Hymel, S. Moral disengagement among children and youth: A meta-analytic review of links to aggressive behavior. Aggress. Behav. 40 (1), 56–68 (2014).

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N. & Lattanner, M. R. Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychol. Bull. 140 (4), 1073–1137 (2014).

Lo Cricchio, M. G., García-Poole, C., te Brinke, L. W., Bianchi, D. & Menesini, E. Moral disengagement and cyberbullying involvement: A systematic review. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 18 (2), 271–311 (2021).

Paciello, M., Tramontano, C., Nocentini, A., Fida, R. & Menesini, E. The role of traditional and online moral disengagement on cyberbullying: Do externalising problems make any difference? Comput. Hum. Behav. 103, 190–198 (2020).

Runions, K. C. & Bak, M. Online moral disengagement, cyberbullying, and cyber-aggression. Cyberpsychol Behav. Soc. Netw. 18 (7), 400–405 (2015).

Jeong, S. H., Cho, H. & Hwang, Y. Media literacy interventions: A meta-analytic review. J. Commun. 62 (3), 454–472 (2012).

Schreurs, L. & Vandenbosch, L. Introducing the Social Media Literacy (SMILE) model with the case of the positivity bias on social media. J. Child. Media. 15 (3), 320–337 (2021).

Livingstone, S. Developing social media literacy: How children learn to interpret risky opportunities on social network sites. Commun 39 (3), 283–303 (2014).

Peter, J. & Valkenburg, P. The effects of internet communication on adolescents’ psychosocial development: An assessment of risks and opportunities. In Media Psychology 678–697. (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Bandura, A. A social cognitive theory of personality. In Handbook of Personality. 154–196. (Guilford, 1999).

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In Handbook of Moral Behavior and Development. (Erlbaum, 1991).

Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychol. 3 (3), 265–299 (2001).

Bandura, A. & Walters, R. H. Adolescent Aggression (Ronald, 1959).

Bandura, A. Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Moral. Educ. 31 (2), 101–119 (2002).

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V. & Pastorelli, C. Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 71 (2), 364–374 (1996).

Maftei, A., Holman, A. C. & Merlici, I. A. Using fake news as means of cyber-bullying: The link with compulsive internet use and online moral disengagement. Comput. Hum. Behav. 127, 107032 (2022).

Bandura, A., Caprara, G. V., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C. & Regalia, C. Sociocognitive self-regulatory mechanisms governing transgressive behavior. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 80 (1), 125–135 (2001).

Hymel, S., Rocke-Henderson, N. & Bonanno, R. A. Moral disengagement: A framework for understanding bullying among adolescents. J. Soc. Sci. 8 (1), 1–11 (2005).

Bandura, A. & Walters, R. H. Social Learning and Personality Development (Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Inc., 1963).

Huesmann, L. R. & Malamuth, N. M. Media violence and antisocial behavior: An overview. J. Soc. Issues. 42 (3), 1–6 (1986).

Gabbiadini, A., Riva, P., Andrighetto, L., Volpato, C. & Bushman, B. J. Interactive effect of moral disengagement and violent video games on self-control, cheating, and aggression. Soc. Psychol. Personal Sci. 5 (4), 451–458 (2014).

Hartmann, T. & Vorderer, P. It’s okay to shoot a character: Moral disengagement in violent video games. J. Commun. 60 (1), 94–119 (2010).

Hartmann, T., Krakowiak, K. M. & Tsay-Vogel, M. How violent video games communicate violence: A literature review and content analysis of moral disengagement factors. Commun. Monogr. 81 (3), 310–332 (2014).

Krakowiak, K. M. & Tsay-Vogel, M. What makes characters’ bad behaviors acceptable? The effects of character motivation and outcome on perceptions, character liking, and moral disengagement. Mass. Commun. Soc. 16 (2), 179–199 (2013).

Ak, Ş., Özdemir, Y. & Sağkal, A. S. Understanding the mediating role of moral disengagement in the association between violent video game playing and bullying/cyberbullying perpetration. Contemp. Sch. Psychol. 26, 376–386 (2022).

Richmond, J. & Wilson, J. C. Are graphic media violence, aggression and moral disengagement related? J. Managerial Psychol. 15 (2), 350–357 (2008).

Yao, M., Zhou, Y., Li, J. & Gao, X. Violent video games exposure and aggression: The role of moral disengagement, anger, hostility, and disinhibition. Aggress. Behav. 45 (6), 662–670 (2019).

Ojeda, M., Del Rey, R. & Hunter, S. C. Longitudinal relationships between sexting and involvement in both bullying and cyberbullying. J. Adolesc. 77, 81–89 (2019).

Van Ouytsel, J., Lu, Y., Ponnet, K., Walrave, M. & Temple, J. R. Longitudinal associations between sexting, cyberbullying, and bullying among adolescents: Cross-lagged panel analysis. J. Adolesc. 73, 36–41 (2019).

Teng, Z., Nie, Q., Guo, C. & Liu, Y. Violent video game exposure and moral disengagement in early adolescence: The moderating effect of moral identity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 77, 54–62 (2017).

Wang, L. & Ngai, S. S. Y. The effects of anonymity, invisibility, asynchrony, and moral disengagement on cyberbullying perpetration among school-aged children in China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 119, 105613 (2020).

Wachs, S. et al. Associations between witnessing and perpetrating online hate speech among adolescents: Testing moderation effects of moral disengagement and empathy. Psychol. Violence. 12 (6), 371–381 (2022).

Caprara, G. V. et al. The contribution of moral disengagement in mediating individual tendencies toward aggression and violence. Dev. Psychol. 50 (1), 71–83 (2014).

Bussey, K., Fitzpatrick, S. & Raman, A. The role of moral disengagement and self-efficacy in cyberbullying. J. Sch. Violence. 14 (1), 30–46 (2015).

Allison, K. R. & Bussey, K. Individual and collective moral influences on intervention in cyberbullying. Comput. Hum. Behav. 74, 7–15 (2017).

Bussey, K., Luo, A., Fitzpatrick, S. & Allison, K. Defending victims of cyberbullying: The role of self-efficacy and moral disengagement. J. Sch. Psychol. 78, 1–12 (2020).

Meter, D. J. & Bauman, S. Moral disengagement about cyberbullying and parental monitoring: Effects on traditional bullying and victimization via cyberbullying involvement. J. Early Adolesc. 38 (3), 303–326 (2018).

Moxey, N. & Bussey, K. Styles of bystander intervention in cyberbullying incidents. Int. J. Bull. Prev. 2, 6–15 (2020).

Aufderheide, P. Media literacy: A report of the national leadership conference on media literacy. The Aspen Institute, (1993). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED365294.pdf (Accessed: 22 Aug 2024).

Livingstone, S. What is media literacy? Intermedia 32 (3), 18–20 (2004).

Hobbs, R. Media Literacy in Action: Questioning the Media (Rowman & Littlefield, 2021).

Hobbs, R. Digital and Media Literacy: A Plan of Action (The Aspen Institute, 2010).

Ofcom Ofcom’s approach to online media literacy. Ofcom, (2021). https://www.ofcom.org.uk/_data/assets/pdf_file/0015/229002/approach-to-online-media-literacy.pdf (Accessed: 22 Aug 2024).

Austin, E. W. The message interpretation process model. In Encyclopedia of Children, Adolescents, and the Media. (Sage Publishing, (2007).

Austin, E. W. et al. The effects of increased cognitive involvement on college students’ interpretations of magazine advertisements for alcohol. Commun. Res. 29, 155–179 (2002).

Austin, E. W., Pinkleton, B. E. & Funabiki, R. P. The desirability paradox in the effects of media literacy training. Commun. Res. 34 (5), 483–506 (2007).

Austin, E. W. & Domgaard, S. The media literacy theory of change and the message interpretation process model. Commun. Theory qtae018 (2024).

Kupersmidt, J. B., Scull, T. M. & Austin, E. W. Media literacy education for elementary school substance use prevention: Study of media detective. Pediatrics 126 (3), 525–531 (2010).

Vahedi, Z., Sibalis, A. & Sutherland, J. E. Are media literacy interventions effective at changing attitudes and intentions towards risky health behaviors in adolescents? A meta-analytic review. J. Adolesc. 67, 140–152 (2018).

Hobbs, R. Measuring the digital and media literacy competencies of children and teens. In Cognitive Development in Digital Contexts 253–274. (Academic, (2017).

Bae, S. M. Characteristics and treatment of cyberviolence trauma in children and adolescents. J. Korean Acad. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry. 35 (3), 169 (2024).

National Information Society Agency. Cyber violence survey data. National Information Society Agency, 2022. (2021). https://www.data.go.kr/data/15106136/fileData.do?recommendDataYn=Y (Accessed: 10 Nov 2022).

Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Guilford Press, 2017).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51 (6), 1173–1182 (1986).

Cohen, J. P., Cohen, S., West, G. & Aiken, L. S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 2003).

Sharma, S., Durand, R. M. & Gur-Arie, O. Identification and analysis of moderator variables. J. Mark. Res. 18 (3), 291–300 (1981).

Hosmer, D. W. & Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2000).

Jones-Jang, S. M., Mortensen, T. & Liu, J. Does media literacy help identification of fake news? Information literacy helps, but other literacies don’t. Am. Behav. Sci. 65 (2), 371–388 (2021).

Swart, J. Tactics of news literacy: How young people access, evaluate, and engage with news on social media. New. Media Soc. 25 (3), 505–521 (2023).

Festinger, L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Stanford University Press, 1957).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Cancer Research and Control from the National Cancer Center of Korea (Grant No. 24H1072).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.-S. contributed to the conceptualization, design, data analysis, and manuscript writing. J.K. supervised the research process, including reviewing and editing the manuscript. H.-S. and J.K. approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, HS., Jun, J.K. Role of moral disengagement and media literacy in the relationships between risky online content exposure and cyberaggression among Korean adolescents. Sci Rep 14, 30877 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81858-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81858-1