Abstract

Red blood cell distribution width (RDW) and albumin separately have been used as mortality predictors for people with cardiovascular disease (CVD). This study aims to explore whether the RDW-to-albumin ratio (RAR) could provide a better prognostication in the CVD population. A systematic search of suitable studies was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and ProQuest until February 1, 2024. Mortality and length of stay outcomes of the highest vs. lowest RAR tertile were pooled using hazard ratio (HR) and standardized mean difference (SMD), respectively. Additionally, a dose-response meta-analysis was performed. Publication bias, subgroup, and sensitivity analyses were conducted to address the causes of heterogeneity. Sixteen studies with 30,933 participants were included in the meta-analysis. Pooled results showed that patients with higher RAR faced a significantly higher risk of mortality (HR 1.88, 95%CI 1.59–2.23). Nonlinearity was observed in the dose-response relationship. Using a reference value of 3 ml/g, each 1 ml/g increase in RAR corresponded to a 27% rise in the mortality HR (HR 1.27, 95%CI 1.16–1.39). Our study demonstrated that elevated RAR values were significantly associated with higher mortality in CVD and exhibited a positive dose-response relationship, suggesting its potential as a novel prognostic biomarker for CVD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite advancements in the treatment of cardiovascular disease (CVD), the global cardiovascular burden has risen significantly in the last 20 years, with the mortality rate increasing from 12.1 million in 1990 to 18.6 million in 2019, according to the Global Burden Disease Study 2019. Furthermore, the trend of CVD burden in several countries, which previously had been decreasing, has reversed in the last decade1. According to the WHO, CVD was responsible for 32% of all deaths worldwide, with stroke and coronary heart disease accounting for 85% of them2. This increase is partly due to an outdated management approach that overlooks individual patient differences by applying uniform treatment protocols3. A paradigm shift is needed in CVD management, focusing on incorporating biological parameters, in order to promote more individualized patient care.

Biomarkers, acting as key indicators of physiological and pathological conditions within our bodies, play crucial roles in the cardiovascular field, aiding in early diagnosis, risk stratification, therapeutic assessment, and patient management4,5. Effective prognosis stratification is essential for prioritizing the treatment given to patients and determining its intensity. Although current biomarkers have prognostic value, their implementation is limited by cost and accessibility6. Many studies have searched for low-cost, widely available, and applicable biomarkers to predict the prognosis of CVD. Among those, red-cell distribution width (RDW) and serum albumin showed promising results. Elevated RDW and decreased serum albumin have been linked to poor outcomes in cardiovascular conditions, offering key prognostic insights7,8. Furthermore, recent studies suggest that biomarkers derived from a combination of individual markers yield superior predictive abilities, and researchers have continually hypothesized methods to enhance the accuracy of albumin by incorporating it with other biomarkers, particularly RDW8,9. RDW-to-albumin ratio (RAR) has been shown to have a higher prognostication value when compared with commonly used inflammatory markers, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)10and Sequential Organ Failure Analysis (SOFA) score11.

Despite several studies linking RAR to mortality in CVD, questions remain regarding the generalizability and robustness of the individual results, and no previous meta-analysis has been done to evaluate this topic comprehensively. Therefore, we undertook a systematic review and meta-analysis to thoroughly assess the role of RAR as a novel prognostic biomarker in CVD, providing a detailed assessment of its prognostic value through dose-response analysis.

Methods

This meta-analysis followed the standards set by the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 and was registered in the PROSPERO database (Registration number CRD42023491805)12. Ethical clearance was not obtained as this study collected secondary data from published studies.

Eligibility criteria

The screening process involved evaluating titles and abstracts of gathered studies, adhering to these selection criteria: (1) research including participants aged 18 years or older diagnosed with CVD, including arrhythmia, aortic dissection, cardiomyopathy, congenital heart disease, cor pulmonale, heart failure, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, coronary heart disease, peripheral artery disease, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary hypertension, rheumatic heart disease, valvular heart disease, venous thrombosis; (2) RAR value was measured in ml/g; (3) reporting either all-cause or cardiovascular mortality as the primary outcome; (4) the study was conducted under an interventional (randomized or non-randomized trial) or observational (case-control, prospective, and retrospective cohort) study design, and (5) written in English. There were no restrictions on the year of publication. Studies were excluded if they had unavailable full texts, involved non-human subjects, or had overlapping populations/outcomes.

Search strategy and study selection

IF, CCZ, WW, and PP executed a comprehensive search for studies available up to February 1, 2024, across multiple databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest), complemented by manual and bibliographic searches for further data. Table 1 describes the keyword employed in the search strategy.

Following this, duplicates removal and abstract screening were conducted by CCZ and PP. IF, CCZ, WW, and PP independently reviewed the full texts of studies that initially met the criteria. Differences of opinion among the authors were settled through collective discussion.

Data extraction

Included studies were extracted independently by authors, using a structured table based on the outcome of interest of this study. Recorded data include the following: author’s name, published year, number of participants, demographic characteristics of participants, type of cardiovascular diseases, follow-up period, and patients’ outcome (all-cause mortality (ACM), cardiovascular mortality).

Quality assessment

The authors independently performed a risk of bias assessment on individual studies. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) is utilized to assess the quality of observational studies13. Results of the assessment were presented in total scores, which classify studies into poor, fair, and good quality.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoints observed in this study were overall ACM, 30-day ACM, 90-day ACM, 1-year ACM, 3-year ACM, and in-hospital mortality. The secondary endpoints included hospital length of stay and ICU length of stay.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we used hazard ratios (HR) for mortality outcomes and standardized mean differences (SMD) using Hedges’ g method for length of stay. Mortality outcomes of the highest vs. lowest RAR categories were pooled using the Generic Inverse Variance method, extracting HRs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from each study. Due to anticipated heterogeneity, a random-effects model was applied. Studies that reported RR as the effect measure were considered equivalent to HR, while studies that reported OR would be converted to HR using a method by Zhang and Yu14, as done in previous studies15,16. All statistical analyses were carried out in R software (version 4.3.2) using meta17, dmetar18, and dosresmeta19 packages. A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

High vs. low RAR values

The included studies categorized the RAR values in various ways: above and below the median, per tertiles, and quartiles. To reduce the heterogeneity of the categorization, we assumed the categorization of all included studies to using per tertile and pooled the effects observed from the highest versus the lowest tertile of RAR values, using the method by Danesh et al.20. The HRs were log-transformed and then multiplied by the factors of 2.18/2.54 or 2.18/1.59 for studies using quartiles or comparing values above versus below the median, respectively. This method has also been widely used in subsequent studies21,22. Heterogeneity in this study was quantified using the Cochran Q (χ2) statistic and I2 statistic test, where I2 of 50% or greater and p< 0.10 of the Q statistic represented evidence of significant heterogeneity23,24. Given the negligible differences in sample sizes across the included studies, we adopted the Paule-Mandel (PM) method with a Hartung-Knapp (HK) adjustment25for estimating between-study variance (tau²), aligning with recent recommendations26,27. Subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate the causes of the heterogeneity according to CVD diagnosis and follow-up time (post-hoc).

Dose-response meta-analysis

Due to the variations in cut-off values for RAR categories across studies, a dose-response meta-analysis was conducted. This employed generalized least-squares regression using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) method for trend estimation, as suggested by Berlin, Greenland–Longnecker, and Orsini28,29. The analysis required the number of cases/person-years, the total number of participants, and the fully adjusted HR with its 95% CI for each category. A one-stage random-effects meta-analysis for aggregated data was employed to include studies with fewer than three RAR categories, with results comparable to the standard two-stage method30. Log estimates were then exponentiated to produce the predicted HRs. The dose-response relationship was assessed using a nonlinear, restricted cubic spline (RCS) model using three knots at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles if the Wald test was significant at a two-sided p-value of < 0.1024. In cases where the Wald test was not significant or a linear model yielded the lowest Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) value, we reported the relationship using a linear model31. Studies that did not report RAR categorization were excluded from this particular analysis.

A non-zero reference group was designated in this analysis. The assigned doses were the mean or median RAR within each reported category. In the absence of these measures, we used the midpoint of the range. For open-ended lower categories, we subtracted the stated lower bound by the adjacent group’s interval width32, while for open upper bounds, half of the adjacent interval width was added to the upper bound15. For studies reporting only a low versus high group, the doses were set at half the value for the low group and one and a half times the value for the high group, respectively. In cases where complete event data within each category were not available, estimations of missing data were made based on the total case count and the hazard ratio (HR) for every category33,34.

Sensitivity analysis

To ensure the robustness of the results, we undertook sensitivity analyses by performing meta-analyses using alternative methods, such as applying a fixed-effects model and different between-study variance estimators, and excluding the HK adjustment. To identify potential outliers, we conducted a ‘leave-one-out’ sensitivity analysis, recalculating pooled effect sizes and heterogeneity results after sequentially omitting one study at a time35. We also repeated the meta-analysis, excluding outliers24. Furthermore, to evaluate the influence of different covariates on RAR’s prognostic significance, a meta-regression analysis was conducted employing the REML approach. Publication bias was assessed through funnel plot inspection and Egger’s regression test36. If publication bias was detected, the Duval and Tweedie trim and fill approach was employed37.

Results

Study selection and quality assessment

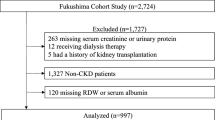

After completing a comprehensive search of databases, 3220 studies were retrieved. Subsequently, 1406 duplicates were removed. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, 15 studies were excluded due to not using English language or involving non-human subjects. Twenty-six studies were screened for eligibility. Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (1) Some included both CVD and non-CVD participants without providing the number of exposed and control groups or effect sizes specifically for the CVD population; (2) In one study, mortality outcome was not reported despite CVD patients being included; and (3) Full texts were unavailable for some studies, preventing eligibility assessment. Three studies were identified through manual searching, resulting in 16 studies included in this meta-analysis (see Fig. 1). All studies were evaluated as being of good quality, with the NOS scale ranging from seven to nine (see Table 2).

Study characteristics

With a total of 16 studies, 30,933 participants were included in this meta-analysis. All included studies were published between 2021 and 2024 and were classified as cohort studies. Demographically, all studies were conducted in Asia and America: eight studies in the United States and eight in China. Most studies included samples from the ICU with various underlying diseases such as aortic aneurysm, acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, stroke, and pulmonary embolism, or involved patients undergoing certain treatments such as Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR), Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), and mechanical thrombectomy. Each study presented different cut-off values and categorizations for RAR. Table 2 outlines the baseline characteristics of the included studies.

Primary endpoints: mortality outcomes

Across all studies, higher RAR values were associated with a greater risk of mortality (HR 1.88, 95%CI 1.59–2.23, p < 0.0001, I2 = 91%; see Fig. 2). Upon stratifying the analysis for overall ACM by the primary CVD diagnoses, a consistent and significant relationship between RAR values and ACM was observed across all CVD subcategories (AMI: HR 2.43, 95%CI 1.52–3.87, I2 = 45%; HF: HR 1.78, 95%CI 1.13–2.81, I2 = 94%; Stroke: HR 1.58, 95%CI 0.94–2.67, I2 = 90%; Other CVD: HR 1.97, 95%CI 1.34–2.89, I2 = 57%; p for interaction = 0.24; see Fig. 3). However, in the subgroup analysis stratified by follow-up duration, the association did not reach statistical significance (Within 30 days: HR 1.58, 95%CI 1.02–2.44, I2 = 86%; Within one year: HR 2.04, 95%CI 1.71–2.45, I2 = 47%; Within three years: HR 1.99, 95%CI 0.93–4.27, I2 = 93%; p for interaction = 0.34; see Fig. 3).

In the dose-response meta-analysis involving 15 studies with 14,387 participants, estimates were presented per 1 ml/g increment in RAR, with a reference point (HR = 1) set at three ml/g, determined by the weighted mean of all assigned reference doses. Three inputs from two studies lacking RAR categorization were omitted from the analysis10,50. We found that the spline model had the lowest AIC value and a significant Wald test result (χ2 = 53, p < 0.001), indicating the best fit and nonlinearity. Consequently, the dose-response relationship was primarily illustrated using the RCS model, with the linear model provided for comparison. In the linear model, for each 1 ml/g increase in RAR, the predicted HR for ACM rose by 27% (HR 1.27, 95%CI 1.16–1.39; p < 0.0001). The spline model showed a substantial increase in HR from the baseline to approximately 5 ml/g before proceeding to produce a more gradual increase afterward (RAR 4ml/g: HR 1.53, 95%CI 1.29–1.80; RAR 5ml/g: HR 1.97, 95%CI 1.54–2.53; RAR 10ml/g: HR 2.93, 95%CI 2.19–3.91; p < 0.0001; see Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table S3 online).

The pooled random-effects analyses indicated that the in-hospital, 30-day, 90-day, and one-year ACM outcomes were statistically significant, while the 3-year ACM was not (In-hospital: HR 1.77, 95%CI 1.20–2.61, I2 = 50%, p = 0.019; 30-day: HR 1.92, 95%CI 1.48–2.48, I2 = 86%, p < 0.001; 90-day: HR 2.38, 95%CI 1.61–3.53, I2 = 59%, p = 0.035; 1-year: HR 2.17, 95%CI 1.73–2.71, I2 = 59%, p < 0.0001; 3-year: HR 1.99, 95%CI 0.93–4.27, p = 0.064; see Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figures S1–5 online).

Secondary endpoints: length of hospital and ICU stay

The pooled results of the length of hospital (3 studies) and ICU (5 studies) stay were both statistically significant (Hospital: SMD 0.62, 95%CI 0.21–1.03, I2 = 91%, p = 0.022; ICU: SMD 0.46, 95%CI 0.93–4.27, p = 0.064; see Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figures S6–S7 online).

Sensitivity analysis, meta-regression, and publication bias

The leave-one-out analysis of the included studies demonstrated minimal variation in effect sizes and no significant change in its direction and significance, except for two outlying studies (see Supplementary Figure S8 online)10,50. The pooled results excluding these studies resulted in a slight increase in the effect size and a substantial decrease in the heterogeneity. Subsequently, the meta-analyses were repeated using other methods, and similar effect size, direction, and significance of association were observed (see Supplementary Table S4 online). The meta-regression analysis revealed no significant association between the modifier variables and ACM (see Supplementary Table S5–S6 online).

Examination of funnel plots visually and analysis through Egger’s test showed a publication bias in the included studies; however, the pooled results after the trim and fill method did not change significantly (HR 1.29, 95%CI 1.00–1.68; p < 0.05; I2 = 91%; see Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Figure S9–S13 online).

Discussion

This meta-analysis is the first to explore the relationship between RAR and mortality in CVD patients, revealing a significant correlation between higher RAR and increased mortality, as well as longer hospital and ICU stays. A nonlinear dose-response relationship was found, with results adjusted for confounding factors. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the findings despite observed heterogeneity.

Previous studies on RDW and albumin levels in CVD populations showed significant but varied predictive values. RDW exhibited a linear relationship with mortality (HR 1.03 per unit increase)34, while albumin showed a J-shaped association53. Our analysis found that RAR provided a stronger and more consistent predictive value (HR 1.27 per ml/g increase) than RDW or albumin alone.

RDW, which measures red blood cell size variation, is a recognized biomarker for inflammation. Elevated RDW levels indicate impaired erythropoiesis, commonly due to chronic inflammation, anemia, or nutritional deficiency, all frequent conditions in CVD54. These factors disrupt bone marrow function, decrease erythropoietin synthesis, and lead to anisocytosis and adverse cardiac remodeling7,55. Serum albumin serves as a multifunctional circulatory protein with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticoagulant, and anti-platelet aggregation activities that are crucial in the pathophysiology of CVD. Hypoalbuminemia reflects conditions like malnutrition, inflammatory syndromes, and hypervolemia. However, unlike RDW, hypoalbuminemia can also worsen CVD conditions by increasing oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and thrombogenic risks9,56. Thus, the combination of these markers may enhance CVD prognostication through better detection of underlying inflammation, oxidative stress, and increased atherothrombotic risk.

Distinct differences in effect sizes exist among specific cardiovascular diseases. AMI exhibited the highest hazard ratio, with a 2.4-fold increased likelihood of mortality (HR 2.43, 95%CI 1.52–3.87, I2= 45%). Beyond the previously stated mechanisms, this could be attributed to alterations in microvascular flow due to elevated RDW55, as well as increased thrombus formation and myocardial edema from hypoalbuminemia in a hyperacute setting9,56. In comparison, heart failure and stroke had lower HRs but still indicated increased risks. Oxidative stress in stroke may impair erythropoiesis, reducing cerebral tissue reperfusion57, while hypoalbuminemia may blunt the anti-inflammatory response58. In heart failure, iron deficiency and neurohormonal activation may cause anisocytosis, increasing cardiovascular stress59. Hypoalbuminemia may also raise the risk of pulmonary edema and diuretic resistance60. The variability in effects across CVDs (Chi² = 4.2, p for interaction = 0.2) highlights the multifaceted nature of CVD pathogenesis. An elevated RAR could prompt more intensive monitoring and earlier, aggressive interventions to prevent mortality, such as ICU admission and treatment intensification.

RAR demonstrated the strongest predictive value for mortality among hematologic biomarkers in CVD populations (HR 1.88), outperforming WBC count (HR 1.64), NLR (HR 1.14 per quartile increase), and hemoglobin levels (HR 0.92)61,62,63. These findings underscore RAR’s robustness as a mortality predictor among commonly used markers in CVD populations.

Despite numerous studies exploring hematological parameters in CVDs56,59, varying cut-off values often introduce interpretation bias. Dose-response meta-analysis offers a novel approach by interpreting RAR as a continuous variable (per 1 ml/g increase) rather than relying solely on categorical groupings, thus mitigating this bias64. Our study demonstrated a significant dose-response relationship between RAR and mortality in CVD populations. Since RAR is derived from routine hematological tests, establishing precise cut-off values for each specific CVD is crucial for its practical application in clinical settings.

This study has several limitations. First, heterogeneity in the analysis could introduce bias, necessitating subgroup and sensitivity analyses. The variability in RAR cut-off values and categorizations among studies may have influenced the findings, though we addressed this through a dose-response meta-analysis. Additionally, several studies were excluded due to unavailable CVD-specific data, potentially causing a publication bias. Lastly, as all studies were conducted in Asia and America, the generalizability of the findings to other regions may be limited.

Several potential sources of heterogeneity in our study were identified. First, variations in CVD types and differences in RAR values across studies likely contributed to the heterogeneity, which we addressed through subgroup analysis based on CVD diagnoses and dose-response analysis. Second, since all studies were cohort designs with expected methodological variability and potential confounders, fully adjusted effect sizes were used. Third, after conducting a leave-one-out meta-analysis and using the find.outliers function in Rstudio, outliers were identified within the included studies. Excluding these outliers in sensitivity analyses reduced heterogeneity substantially from 91 to 58%. Finally, although Egger’s regression test indicated publication bias and small-study effects, trim-and-fill analysis confirmed the results remained significant.

As the field evolves, it is imperative to recognize the need for future research and potential guideline development based on standardized approaches. The emphasis on prospective studies to determine causality, along with further research involving larger, well-defined, or homogeneous cohorts, is essential to solidify the role of RAR as a reliable biomarker for predicting mortality in CVD patients. Additionally, meta-analyses of the association between RAR and mortality outcomes across different CVDs are crucial to further establish its clinical relevance.

Conclusion

This systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis represent the initial study to illustrate a noteworthy association between elevated RAR values and increased mortality risk and length of stay outcomes, along with a significant positive dose-response relationship among CVD populations. These findings advocate for incorporating RAR into routine clinical evaluations, highlighting its potential role as a cost-effective and accessible prognostic tool for mortality risk assessment in patients with CVD.

Future research is needed to confirm these results and further investigate the potential link between RAR and all-cause mortality in CVD.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are not available for public access due to restrictions associated with intellectual property rights. However, these datasets are accessible upon request to the corresponding authors. Interested parties are encouraged to reach out to the corresponding authors directly to discuss the terms under which access to the datasets may be granted.

References

Mensah, G. A., Fuster, V., Murray, C. J. L. & Roth, G. A. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and risks collaborators. Global Burden of Cardiovascular diseases and risks, 1990–2022. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 82, 2350–2473 (2023).

WHO, W. H. O. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). (2021).

Leopold, J. A. & Loscalzo, J. Emerging role of Precision Medicine in Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 122, 1302–1315 (2018).

Lindholm, D. et al. Biomarker-based risk model to Predict Cardiovascular Mortality in patients with stable coronary disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 70, 813–826 (2017).

Wong, Y. K. & Tse, H. F. Circulating biomarkers for Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction in patients with Cardiovascular Disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 8, 713191 (2021).

Dhingra, R. & Vasan, R. S. Biomarkers in cardiovascular disease: statistical assessment and section on key novel heart failure biomarkers. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 27, 123–133 (2017).

Talarico, M. et al. Red cell distribution Width and Patient Outcome in Cardiovascular Disease: a real-world’’ analysis. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 8, 120 (2021).

Manolis, A. A., Manolis, T. A., Melita, H., Mikhailidis, D. P. & Manolis, A. S. Low serum albumin: a neglected predictor in patients with cardiovascular disease. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 102, 24–39 (2022).

Arques, S. Serum albumin and cardiovascular disease: state-of-the-art review. Ann. Cardiol. Angeiol (Paris). 69, 192–200 (2020).

Zhao, J., Feng, J., Ma, Q., Li, C. & Qiu, F. Prognostic value of inflammation biomarkers for 30-day mortality in critically ill patients with stroke. Front. Neurol. 14, 1110347 (2023).

Guo, L., Chen, D., Cheng, B., Gong, Y. & Wang, B. Prognostic Value of the Red Blood Cell Distribution Width-to-Albumin Ratio in Critically Ill Older Patients with Acute Kidney Injury: A Retrospective Database Study. Emerg. Med. Int. 1–11 (2023). (2023).

Page, M. J. et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ n71 doi: (2021). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Stang, A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 25, 603–605 (2010).

Zhang, J. & Yu, K. F. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in Cohort studies of Common outcomes. JAMA 280, 1690 (1998).

Semnani-Azad, Z. et al. Association of Major Food Sources of fructose-containing sugars with Incident Metabolic Syndrome: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open. 3, e209993 (2020).

Banach, M. et al. The association between daily step count and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 30, 1975–1985 (2023).

Balduzzi, S., Rücker, G. & Schwarzer, G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid. Based Ment Health. 22, 153–160 (2019).

Harrer, M., Cuijpers, P., Furukawa, T. A. & Ebert, D. D. Doing Meta-Analysis with R: A Hands-On Guide (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003107347

Crippa, A. & Orsini, N. Multivariate Dose-Response Meta-Analysis: the dosresmeta R Package. J. Stat. Softw. 72, (2016).

Danesh, J., Collins, R., Appleby, P. & Peto, R. Association of Fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, Albumin, or Leukocyte Count with Coronary Heart Disease: Meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA 279, 1477 (1998).

Li, L. et al. Serum amyloid A and risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Ren. Fail. 45, 2250877 (2023).

Schlesinger, S., Sonntag, S. R., Lieb, W. & Maas, R. Asymmetric and Symmetric Dimethylarginine as risk markers for total Mortality and Cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLOS ONE. 11, e0165811 (2016).

Higgins, J. P. T. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21, 1539–1558 (2002).

Higgins, J. P. T. et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. vol. version 6.4 (Cochrane, Chichester (UK), (2023).

Knapp, G. & Hartung, J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat. Med. 22, 2693–2710 (2003).

Novianti, P. W., Roes, K. C. B. & Van Der Tweel, I. Estimation of between-trial variance in sequential meta-analyses: a simulation study. Contemp. Clin. Trials. 37, 129–138 (2014).

Veroniki, A. A. et al. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta‐analysis. Res. Synth. Methods. 7, 55–79 (2016).

Berlin, J. A., Longnecker, M. P. & Greenland, S. Meta-analysis of epidemiologic dose-response data. Epidemiology 4, 218–228 (1993).

Orsini, N., Li, R., Wolk, A., Khudyakov, P. & Spiegelman, D. Meta-analysis for Linear and Nonlinear Dose-Response relations: examples, an evaluation of approximations, and Software. Am. J. Epidemiol. 175, 66–73 (2012).

Crippa, A., Discacciati, A., Bottai, M., Spiegelman, D. & Orsini, N. One-stage dose–response meta-analysis for aggregated data. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 28, 1579–1596 (2019).

Discacciati, A., Crippa, A. & Orsini, N. Goodness of fit tools for dose-response meta-analysis of binary outcomes. Res. Synth. Methods. 8, 149–160 (2017).

Ekelund, U. et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ 366, l4570 (2019).

Bekkering, G. E. et al. How much of the data published in observational studies of the association between diet and prostate or bladder cancer is usable for meta-analysis? Am. J. Epidemiol. 167, 1017–1026 (2008).

Hou, H. et al. An overall and dose-response meta-analysis of red blood cell distribution width and CVD outcomes. Sci. Rep. 7, 43420 (2017).

Patsopoulos, N. A., Evangelou, E. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Sensitivity of between-study heterogeneity in meta-analysis: proposed metrics and empirical evaluation. Int. J. Epidemiol. 37, 1148–1157 (2008).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315, 629–634 (1997).

Duval, S. & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for Publication Bias in Meta‐Analysis. Biometrics 56, 455–463 (2000).

Long, J. et al. Association between Red Blood cell distribution width-to-albumin ratio and prognosis of patients with aortic aneurysms. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 6287–6294 (2021).

Li, H. & Xu, Y. Association between red blood cell distribution width-to-albumin ratio and prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23, 66 (2023).

Gu, Y., Yang, D., Huang, Z., Chen, Y. & Dai, Z. Relationship between red blood cell distribution width-to-albumin ratio and outcome of septic patients with atrial fibrillation: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 22, 538 (2022).

Jian, L., Zhang, Z., Zhou, Q., Duan, X. & Ge, L. Red cell distribution Width/Albumin ratio: a predictor of In-Hospital all-cause mortality in patients with Acute myocardial infarction in the ICU. Int. J. Gen. Med. 16, 745–756 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. Relationship between the ratio of red cell distribution width to Albumin and 28-Day mortality among Chinese patients over 80 years with Atrial Fibrillation. Gerontology 69, 1471–1481 (2023).

Wang, S., Xiao, Q., Lin, Q. & Li, Y. Acute Heart Failure Patients with a High Red Blood Cell Distribution Width-to-Albumin Ratio Have an Increased Risk of All-Cause Mortality. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.17.23288709 doi:10.1101/2023.04.17.23288709.

Meng, L. et al. Association of red blood cell distribution width-to-albumin ratio with mortality in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. PLOS ONE. 18, e0286561 (2023).

Ni, Q., Wang, X., Wang, J. & Chen, P. The red blood cell distribution width-albumin ratio: a promising predictor of mortality in heart failure patients — a cohort study. Clin. Chim. Acta. 527, 38–46 (2022).

Zhao, N. et al. The red blood cell distribution width–albumin ratio: a promising predictor of Mortality in Stroke patients. Int. J. Gen. Med. 14, 3737–3747 (2021).

Li, D., Ruan, Z. & Wu, B. Association of Red Blood cell distribution width-albumin ratio for Acute myocardial infarction patients with mortality: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Appl. Thromb. 28, 107602962211212 (2022).

Liu, P. et al. RDW-to-ALB Ratio Is an Independent Predictor for 30-Day All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Retrospective Analysis from the MIMIC-IV Database. Behav. Neurol. 1–11 (2022). (2022).

Weng, Y. et al. The ratio of red blood cell distribution width to albumin is correlated with all-cause mortality of patients after percutaneous coronary intervention – a Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 869816 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width/Albumin Ratio Is a Novel Risk Factor of Incidence and Long-Term Mortality in Chronic Heart Failure Patients: Three Large Cohorts from China and America. http://medrxiv.org/lookup/doi/ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.07.23295180 doi:10.1101/2023.09.07.23295180.

Ding, C., Zhang, Z., Qiu, J., Du, D. & Liu, Z. Association of red blood cell distribution width to albumin ratio with the prognosis of acute severe pulmonary embolism: a cohort study. Med. (Baltim). 102, e36141 (2023).

Zhou, P. et al. Association between red blood cell distribution width-to‐albumin ratio and prognosis in non‐ischaemic heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. ehf2.14628 https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.14628 (2024).

Li, X. et al. J-shaped association between serum albumin levels and long-term mortality of cardiovascular disease: experience in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (2011–2014). Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 1073120 (2022).

Alfaddagh, A. et al. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 4, 100130 (2020).

Arkew, M., Gemechu, K., Haile, K. & Asmerom, H. Red blood cell distribution Width as Novel Biomarker in Cardiovascular diseases: a Literature Review. J. Blood Med. 13, 413–424 (2022).

Yoshioka, G., Tanaka, A., Goriki, Y. & Node, K. The role of albumin level in cardiovascular disease: a review of recent research advances. J. Lab. Precis Med. 8, 7–7 (2023).

Salvagno, G. L., Sanchis-Gomar, F., Picanza, A. & Lippi, G. Red blood cell distribution width: a simple parameter with multiple clinical applications. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 52, 86–105 (2015).

Bucci, T. et al. Albumin levels and risk of Early Cardiovascular complications after ischemic stroke: a propensity-matched analysis of a Global Federated Health Network. Stroke 55, 604–612 (2024).

Xanthopoulos, A. et al. Red blood cell distribution Width in Heart failure: pathophysiology, Prognostic Role, controversies and dilemmas. J. Clin. Med. 11, 1951 (2022).

Arques, S. & Ambrosi, P. Human serum albumin in the clinical syndrome of heart failure. J. Card Fail. 17, 451–458 (2011).

Welsh, C. et al. Association of Total and Differential Leukocyte counts with Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in the UK Biobank. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 38, 1415–1423 (2018).

Song, M., Graubard, B. I., Rabkin, C. S. & Engels, E. A. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and mortality in the United States general population. Sci. Rep. 11, 464 (2021).

Cleland, J. G. F. et al. Prevalence and outcomes of Anemia and hematinic deficiencies in patients with Chronic Heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 1, 539 (2016).

Crippa, A. & Orsini, N. Dose-response meta-analysis of differences in means. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 16, 91 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We are deeply thankful to the committed and proficient team at the Department of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Airlangga–Dr. Soetomo General Academic Hospital in Surabaya, Indonesia. Their indispensable inputs were crucial to the successful completion of this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IF provided the research concept and design. IF, CCZ, WW, and PP conducted literature searches and reviews, collected data, developed the research methodology, wrote the main manuscript text, and prepared all supplementary materials. WW and CCZ prepared Tables 1 and 2. IF and PP prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. IF and CCZ prepared Fig. 4. IF, DS, and PP analyzed the data. YHO, PBT, ADL, and JNA reviewed and revised the research methodology, edited the manuscript, and supervised the research. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arba, I.F., Multazam, C.E.C.Z., Widiarti, W. et al. A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of red blood cell distribution width to albumin ratio as mortality predictor in cardiovascular disease. Sci Rep 15, 32053 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81876-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81876-z