Abstract

Patients with liver cirrhosis often experience factors such as malnutrition and lack of exercise, leading to reduced quality of life. Insufficient social support is related to self-management in patients with chronic diseases. Therefore, this study explores the mediating role of social support in the relationship between self-management and quality of life, analyzing the impact of exercise frequency and malnutrition risk assessment on social support, self-management, and quality of life. Using a convenience sampling method, cross-sectional data were collected from 257 patients with liver cirrhosis at the infectious disease department of a tertiary hospital in Zunyi, China, from 2021 to 2022. The patients were evaluated using a demographic questionnaire, the Self-Management Behavior Scale for Liver Cirrhosis Patients, the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), and the Royal Free Hospital Nutritional Prioritizing Tool (RFH-NPT). Data were analyzed using SPSS and PROCESS software.

-

(1)

Patients in the decompensated stage of liver cirrhosis and those classified in Child–Pugh class B/C had lower scores in self-management, quality of life, and social support compared to patients in the compensated stage of liver cirrhosis and those classified in Child–Pugh Class A.

-

(2)

Quality of life was positively correlated with both social support and self-management (r = 0.668, r = 0.665, both P < 0.001).

-

(3)

Mediation analysis showed that self-management had a direct predictive effect on quality of life. Social support had a mediating effect between self-management and quality of life, with an indirect effect of 0.489 (95% CI: 0.362, 0.629), accounting for 40.58% of the total effect.

-

(4)

Exercise frequency and malnutrition risk assessment were independent influencing factors for social support, self-management, and quality of life.

-

(5)

In the regression model, after excluding confounding factors, Model I explained 14% of the variance in quality of life due to control variables, Model II explained 49.5%, and when social support was added, Model III explained 56.9% of the variance in quality of life.

Under the mediating role of social support, self-management can improve quality of life. Exercise frequency and malnutrition risk assessment, as independent influencing factors, also modulate social support and self-management. These findings underscore the importance of strengthening social support and developing self-management programs targeting exercise and nutrition to enhance the quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Liver cirrhosis is a major global public health challenge1. With the rising prevalence of metabolic syndrome and increased alcohol abuse, the incidence and clinical impact of liver cirrhosis continue to rise globally2,3. The symptom prevalence among patients with liver cirrhosis is similar to that of other advanced-stage patients, and its complications lead to high hospitalization and mortality rates, along with impaired quality of life1,4. Over one-third of patients experience muscle cramps, malnutrition, sleep disorders, and depression. Quality of life is affected not only by the disease itself but also by social support, self-management, lack of disease-related knowledge, and psychological factors5,6.

Quality of life is a multidimensional concept that comprehensively assesses an individual’s physical, psychological, and social satisfaction. Research has shown that the chronic nature of liver cirrhosis and its potential severe complications lead to significantly impaired quality of life4. Malnutrition is a serious complication that increases mortality7,8, with an incidence rate ranging from 23 to 60%9. Liver damage and impaired function can significantly reduce nutrient absorption, and decreased muscle mass accompanied by sarcopenia results in reduced exercise frequency. Insufficient exercise and high nutritional risk directly lead to decreased quality of life, disease progression, increased complication rates, and worsened clinical outcomes. A decline in quality of life can affect a patient’s motivation to continue treatment, making it crucial to improve their disease self-management ability.

The focus of self-management is to enable individuals to maintain their nutritional status through daily life activities, diet, monitoring of disease, and medication, while engaging in physical activities and adapting to the psychological demands of their condition. Studies have shown that higher self-management abilities can effectively improve the health, functional status, knowledge, treatment adherence, and quality of life of patients with chronic diseases10,11. Social support typically refers to all the social relationships that provide assistance when a person faces difficulties. Research indicates that higher levels of social support have positive effects and contribute to improved quality of life12,13,14.

Although studies have shown associations between social support, self-management behaviors, and quality of life in chronic diseases, it is unclear whether these relationships also exist in patients with liver cirrhosis. This study employs a mediation model to investigate the relationships between social support, self-management, and quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis. The following hypotheses are proposed: (1) social support mediates the relationship between self-management and quality of life; (2) exercise frequency and malnutrition risk assessment independently affect social support, self-management, and quality of life.

Methods

Study design and participants

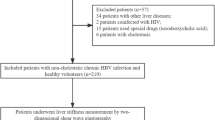

From July 2021 to December 2022, data were collected from 257 liver cirrhosis patients attending the infectious disease department of a tertiary hospital in Zunyi, China, using a convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) meeting the diagnostic criteria for liver cirrhosis as outlined in the "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Liver Cirrhosis"15; (2) age ≥ 18 years; (3) agreement to participate in the study after being informed of the study’s objectives, and signing an informed consent form; (4) no cognitive or communication impairments, and the ability to correctly read, understand, and respond to questions. The exclusion criteria were: (1) the presence of mental or psychological disorders; (2) comorbidities such as tumors or severe cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.

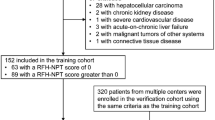

This study employed a structural equation model to test the moderating and mediating effects. Data were collected through a demographic survey, the Self-Management Behavior Scale for Liver Cirrhosis Patients, the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ), the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), and the Royal Free Hospital Nutritional Prioritizing Tool (RFH-NPT). A total of 386 liver cirrhosis patients met the initial inclusion criteria and were selected for screening. Among these patients, 115 met the exclusion criteria and were deemed ineligible for the study. Questionnaires were distributed to the remaining 271 eligible patients, and 257 valid responses were collected, resulting in a valid response rate of 94.83%. The final sample size was 257 patients (see Fig. 1).

To ensure the quality of the questionnaires, the surveyors underwent professional training. After obtaining informed consent from the participants, questionnaires were distributed for self-administration, avoiding any suggestive language. For patients who were illiterate or otherwise unable to complete the questionnaires on their own, the surveyors read the questions to them and filled in the responses based on the participants’ answers. This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University (ZMU) (Ethics Approval No. KLLY-2021–149). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods followed the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Medical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of ZMU.

Measures

Self-management

The Self-Management Behavior Scale for Liver Cirrhosis Patients, developed by Wang Qian et al.16 based on self-management theory and referencing the "Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Liver Cirrhosis" and the "EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines" (2010), was used in this study. The scale comprises four dimensions: daily life management (7 items), diet management (7 items), disease monitoring management (5 items), and medication management (5 items), with a total of 24 items. A 4-point Likert scale was used for evaluation, ranging from 1 (“never”) to 4 (“always”). Total scores range from 24 to 96, with higher scores indicating better self-management behavior. The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.80.

Quality of life

The Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ) is a disease-specific scale used to evaluate the quality of life in patients with liver disease. The CLDQ was developed by Younossi et al.17 and was translated into Chinese by Wu Chuanghong et al.18. The questionnaire includes six dimensions: abdominal symptoms (3 items), fatigue (5 items), general symptoms (5 items), activity (3 items), emotional function (8 items), and anxiety (5 items), with a total of 29 items. A 7-point rating scale is used, with total scores ranging from 29 to 203. Higher scores indicate better quality of life. The test–retest Cronbach’s alpha for the dimensions of the questionnaire ranged from 0.75 to 0.90.

Social support

The Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS) was developed by Chinese researcher Xiao Shuiyuan19. This scale comprises three dimensions with a total of 10 items: subjective support (4 items), objective support (3 items), and the utilization of social support (3 items). Subjective support scores are derived from items 1, 3, 4, and 5; objective support scores come from items 2, 6, and 7; and support utilization is based on items 8 and 9. The total score is the sum of the scores from all 10 items, ranging from 12 to 66, with higher scores indicating greater levels of social support. The Cronbach’s alpha for the items in the scale ranges from 0.890 to 0.940, demonstrating good reliability and validity.

Nutritional risk screening tool

The Royal Free Hospital Nutrition Prioritization Tool (RFH-NPT)20 was employed, which is recommended by EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on nutrition in chronic liver disease21 as the optimal nutritional screening tool for patients with liver cirrhosis. It has high practicality and sensitivity, utilizing simple questions and measurements to score nutritional risk. The assessment includes factors such as acute alcoholic hepatitis or nasogastric nutrition, fluid retention and its impact on dietary intake, body mass index (BMI), unintended weight loss, and reduced dietary intake. Patients are classified into low risk (0 points), moderate risk (1 point), and high risk (2–7 points).

Demographic information

A self-designed questionnaire was used to collect background information, including age, gender, ethnicity, location, living conditions, occupation, marital status, level of social and cultural status, smoking and drinking history (inquiry into whether the patient smokes or drinks, including daily amounts, cumulative years, and years since quitting), exercise frequency (including the number of times, duration, and types of exercise per week), medical payment methods, personal monthly income, average monthly family income, hospitalization duration, hospitalization costs, and other relevant demographic data. Disease-related reference data, such as etiology, disease duration, severity, and Child–Pugh classification, were obtained through the medical system.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 29.0. Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage) were performed on the sample. A correlation matrix was calculated for the dimensions of social support, self-management, and quality of life. Chi-square tests were used for binary variables, while t-tests were applied for continuous variables that met normal distribution assumptions. The mediation effect of social support on self-management and quality of life was analyzed using PROCESS (Model 4) through a non-parametric bootstrap procedure, with a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (CI) and a bootstrap resampling number set to 5000. Hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed to explain the variance changes between the models.

Results

Demographic characteristics of patients

Among the 257 patients with liver cirrhosis, 170 were male (66.15%) and 87 were female (33.85%), with an average age of 53.47 ± 9.67 years. Approximately half of the patients had an education level of elementary school or lower (51.36%), and 61.87% of the patients came from rural areas. The largest proportion of personal monthly income was in the ranges of 1000–3000 CNY and 3001–5000 CNY, while more than half of the families (67.70%) reported a monthly income within the 1000–3000 CNY range. More than half of the patients had a hospitalization duration of ≥ 10 days, with hospitalization costs exceeding 10,000 CNY. (See Table 1).

Among the disease data for the 257 liver cirrhosis patients, the largest proportion had cirrhosis resulting from hepatitis B, accounting for 148 patients (57.59%), with 84.44% of these patients in the decompensated stage and 73.15% classified in Child–Pugh class (B/C). Additionally, 56.42% of the patients reported exercising less than three times a week, and 52.1% were assessed as having a high nutritional risk. (See Table 2).

Scores of disease severity, child–pugh classification, social support, self-management, and quality of life

Tables 3 and 4 display the scores for disease severity, Child–Pugh classification, social support, self-management, and quality of life among liver cirrhosis patients. The total scores for social support, self-management, and quality of life were all lower in patients with decompensated cirrhosis compared to those with compensated cirrhosis. Additionally, patients in Child–Pugh class (B/C) had lower total scores in all three categories compared to those in Child–Pugh class A.

Univariate analysis of exercise frequency and nutritional risk assessment

Tables 5 and 6 show the results of social support and self-management in relation to quality of life, grouped by exercise frequency and nutritional risk assessment. In the statistical analysis based on exercise frequency, all variables except dietary management showed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05), with patients exercising ≥ 3 times a week scoring higher than those exercising < 3 times per week. In the analysis based on nutritional risk assessment, all three scales showed statistically significant differences (P < 0.05), with patients at low to moderate nutritional risk scoring higher than those at high nutritional risk.

Correlation analysis among social support, self-management, and quality of life

A correlation matrix was established to assess the levels of correlation among social support, self-management, and quality of life. As shown in Table 7, the total quality of life score was positively correlated with both the total social support and self-management scores (r = 0.668, 0.665; both P < 0.001), indicating significant correlations among all variables.

Mediation analysis

Table 8 presents a hierarchical multiple regression analysis to assess the effects of gender, exercise frequency, nutritional risk assessment, self-management, and social support on the quality of life of liver cirrhosis patients. The variables "gender," "exercise frequency," and "nutritional risk assessment" were added in Model I, followed by the "total score of self-management" in Model II, and the "total score of social support" in Model III. Excluding the confounding factor of gender, Model I explained 14% of the variance in quality of life, while Model II explained 49.5%. When the social support variable was added to Model III, which also excluded the confounding factor of gender, this model explained 56.9% of the variance in quality of life.

The results of the mediation effect analysis indicated that the direct effect of self-management on quality of life, as well as the mediating effect of social support, had a 95% confidence interval that did not include zero, demonstrating statistical significance. This suggests that self-management in liver cirrhosis patients not only directly predicts quality of life but also predicts it through the mediating role of social support. The direct effect of self-management on quality of life was 0.716, while the mediating effect of social support between self-management and quality of life was 0.489, with a total effect of 1.205. The mediating effect accounted for 40.58% of the total effect (0.489 / 1.205). The breakdown of the mediating effect is shown in Table 9. The mediation effect model is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Discussion

This study aims to verify the mediating role of social support between self-management and quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis, as well as the independent effects of exercise frequency and nutritional risk assessment on social support, self-management, and quality of life. The results indicate that self-management in liver cirrhosis patients directly predicts quality of life, with social support playing a partial mediating role, accounting for 40.58% of the total effect. Additionally, exercise frequency and nutritional risk assessment independently influence all three factors, with patients exercising three or more times a week and those at low to moderate nutritional risk achieving higher scores. Understanding the factors and mechanisms affecting the quality of life in liver cirrhosis is crucial for developing self-management intervention programs in clinical practice.

Social support is a significant factor influencing self-management behaviors in patients with chronic hepatitis B22, while patients with liver cirrhosis often have weak functional social relationships (low social support or feelings of loneliness)23. Consistent with our findings, patients with decompensated cirrhosis and those classified in Child–Pugh (B/C) scored lower in self-management, quality of life, and social support compared to patients with compensated liver cirrhosis and those classified in Child–Pugh A. Insufficient social support is associated with decreased quality of life and increased mortality rates, with liver cirrhosis patients experiencing low social support having higher mortality rates than those with medium to high social support23,24. Research indicates that social support and social interactions are crucial for patients to successfully combat disease and engage in self-management behaviors; a lack of support is a barrier to self-management25.

A global burden of disease (GBD) study26 estimates that there are approximately 112 million patients with compensated liver cirrhosis worldwide, with disease burden varying by location, healthcare system, ethnicity, quality of education, and socioeconomic status27. This study was conducted in the economically and culturally underdeveloped western region of China, where more than half of the patients come from rural areas with lower educational levels. The progression of the disease leads to prolonged hospitalization and high costs, which, coupled with significant disparities in personal and family income, complicate the situation. Although China has made progress in achieving universal health coverage, out-of-pocket medical expenses remain relatively high compared to Germany, the United States, and Singapore28. Particularly in rural families in western China, there are substantial regional disparities in economic development, health resource allocation, and population health status29. This contributes to patients’ negative coping mechanisms regarding disease, unmet psychosocial and physical needs, insufficient disease management, and a desire for support from family, friends, and healthcare providers30,31. Our investigation into social support revealed that patients lacked sufficient community resources to manage the onset and progression of liver cirrhosis, negatively affecting their self-management capabilities. Therefore, it is crucial to assist patients in obtaining support from families, healthcare providers, communities, and other sources to cope with the disease and enhance their self-management behaviors.

The results of this study indicate that exercise frequency and nutritional risk assessment serve as independent influencing factors, with liver cirrhosis patients exercising less than three times a week and those at high nutritional risk scoring lower. Nutritional deficiencies are severe complications of cirrhosis, with an incidence rate of 23% to 60%9, which also impacts exercise frequency. As the disease progresses, weakness often overlaps with malnutrition9,32, and sarcopenia increases the risk of falls and fractures, leading to reduced activity levels and decreased exercise frequency in cirrhosis patients. Factors contributing to malnutrition include reduced energy and protein intake, inflammation, malabsorption, altered nutritional metabolism, metabolic rate increases, and gut microbiome imbalances. While malnutrition may not be as apparent in compensated cirrhosis, it is associated with disease progression and has a higher incidence in decompensated patients 7,9. Additionally, social support factors, such as economic pressure and insufficient caregiver supervision, are significant reasons for low exercise frequency and high nutritional risk among patients. Multiple studies have shown that exercise interventions at least three times a week can effectively improve muscle mass and physical function in cirrhosis patients, thereby enhancing their quality of life33,34,35,36. Pilcher et al.37 defined social support as a self-control resource. As suggested by self-exhaustion theory, poor self-management behaviors stem from a lack of self-control resources, which is a fundamental cause of management failure. The absence of social support in areas like alcohol consumption, smoking, poor diet, and non-adherence to medical regimens is a significant barrier to self-management38. Thus, in addition to pharmacotherapy, incorporating exercise prescriptions into routine care for cirrhosis patients39 can improve nutritional deficiencies through moderate exercise and adequate intake of protein, energy, and micronutrients40,41,42. Engaging support from family, friends, healthcare workers, and peers can enhance self-management capabilities and further promote improvements in quality of life.

In this study, the quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis was positively correlated with social support and self-management (r = 0.668, 0.665; both P < 0.001). In the structural model, social support and self-management skills were significant predictors of quality of life in cirrhosis patients, with sufficient social support linked to higher survival rates24. Research in the United States, Mexico, and Canada also emphasizes the necessity of understanding the driving factors and barriers of social support for self-management and health improvement in chronic diseases43,44,45. Social support directly influences self-management abilities and disease knowledge, and indirectly affects quality of life through self-management capabilities. This may relate to the stigma associated with hepatitis B infections and a reduced support network, limiting patients’ opportunities to express their feelings and concerns, thereby undermining their confidence in disease control. Furthermore, social support plays a crucial role in acquiring disease-related knowledge, and health-related education promoting effective self-management plans is vital for successful self-management. Health education can significantly enhance health outcomes in chronic disease patients46,47 and help strengthen behavioral change antecedents such as self-awareness, information, knowledge, skills, beliefs, attitudes, and values.

Research indicates that the self-management levels of patients with chronic liver disease are generally low to moderate48. Additionally, approximately 10% to 45% of chronic liver disease patients may revert to unhealthy habits, such as drinking alcohol, smoking, and adopting unhealthy lifestyles, which can lead to decreased survival rates49,50. Therefore, it is especially important to establish a comprehensive and ongoing social support system to enhance their quality of life. With the rapid advancement of technology, online social support through platforms like internet resources, home interventions, and mobile communities has become prevalent in chronic disease management51,52. This can complement offline support from caregivers, healthcare workers, and medical institutions by providing self-management intervention programs that emphasize exercise and nutrition, alleviating patients’ financial burdens, enhancing their sense of self-efficacy, and further reducing readmission rates, delaying disease progression, and improving survival rates.

This study has some limitations. First, the sample was drawn from patients at local hospitals in China, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the data were collected through a cross-sectional survey, meaning that the conclusions can only be interpreted statistically, and longitudinal data may be needed to further explore these relationships. Third, the sample size was relatively small, which may introduce bias. Therefore, further research is needed to address these limitations to improve the reliability and generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

This study investigated the mediating role of social support between self-management and quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis. The results indicate that self-management can enhance quality of life through the mediating effects of social support. Additionally, exercise frequency and nutritional risk assessment serve as independent influencing factors that also modulate the relationship between social support and self-management. Social support is recommended to be strengthened to develop self-management programs focused on exercise and nutrition to improve the quality of life for patients with liver cirrhosis.

Supplementary materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://kdocs.cn/l/cnGGJAZJ3hI2.

Data availability

Data associated with this study can be obtained by reasonable request to the corresponding author (P.Y.).

References

Gines, P. et al. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 398(10308), 1359–1376 (2021).

Moon, A. M., Singal, A. G. & Tapper, E. B. Contemporary epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18(12), 2650–2666 (2020).

Huang, D. Q. et al. Global epidemiology of alcohol-associated cirrhosis and HCC: trends, projections and risk factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20(1), 37–49 (2023).

Peng, J. K. et al. Symptom prevalence and quality of life of patients with end-stage liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat. Med. 33(1), 24–36 (2019).

Dong, N. et al. Self-management behaviors among patients with liver cirrhosis in Shanghai, China: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Nurs. Res. 29(7), 448–459 (2020).

Volk, M. L., Fisher, N. & Fontana, R. J. Patient knowledge about disease self-management in cirrhosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 108(3), 302–305 (2013).

Traub, J. et al. Malnutrition in patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutrients 13(2), 540 (2021).

Du, X. et al. The impact of individualized nutritional management strategies combined with transitional care models on the nutritional status and quality of life of patients with liver cirrhosis. Nurs. Res. 37(22), 4096–4100 (2023).

Bunchorntavakul, C. & Reddy, K. R. Review article: malnutrition/sarcopenia and frailty in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 51(1), 64–77 (2020).

Allegrante, J. P., Wells, M. T. & Peterson, J. C. Interventions to support behavioral self-management of chronic diseases. Annu. Rev. Public Health 40, 127–146 (2019).

Martin-Nunez, J. et al. Systematic review of self-management programs for prostate cancer patients, a quality of life and self-efficacy meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 107, 107583 (2023).

Luszczynska, A. et al. Social support and quality of life among lung cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology 22(10), 2160–2168 (2013).

Yang, Y. et al. Social support and quality of life in migrant workers: Focusing on the mediating effect of healthy lifestyle. Front. Public Health 11, 1061579 (2023).

Charlton, R. A., McQuaid, G. A. & Wallace, G. L. Social support and links to quality of life among middle-aged and older autistic adults. Autism 27(1), 92–104 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of liver cirrhosis. J. Clin. Hepatobiliary Dis. 35(11), 2408–2425 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Development of a self-management behavior scale for patients with liver cirrhosis[. Chin. Nurs. J. 49(12), 1515–1520 (2014).

Younossi, Z. M. et al. Development of a disease specific questionnaire to measure health related quality of life in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut 45(2), 295–300 (1999).

Wu, C. et al. Trial of a chronic liver disease questionnaire in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 01, 60–62 (2003).

Xiao, S. The theoretical basis and research application of the Social Support Rating Scale. J. Clin. Psychiatry 02, 98–100 (1994).

Zhang, P. et al. Differences in nutritional risk assessment between NRS2002, RFH-NPT and LDUST in cirrhotic patients. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 3306 (2023).

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on nutrition in chronic liver disease. J. Hepatol. 70(1), 172–193 ( 2019)

Kong, L. N. et al. Self-management behaviors in adults with chronic hepatitis B: A structural equation model. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 116, 103382 (2021).

Askgaard, G. et al. Social support and risk of mortality in cirrhosis: A cohort study. JHEP Rep. 5(1), 100600 (2023).

Garcia, M. N. et al. Inadequate social support decreases survival in decompensated liver cirrhosis patients. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 46(1), 28–38 (2023).

Chaleshgar-Kordasiabi, M. et al. Barriers and reinforcing factors to self-management behaviour in rheumatoid arthritis patients: A qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Care 16(2), 241–250 (2018).

The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5(3), 45–266. (2020)

Huang, D. Q. et al. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis - aetiology, trends and predictions. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20(6), 388–398 (2023).

Chen, W., Ma, Y. & Yu, C. Unmet chronic care needs and insufficient nurse staffing to achieve universal health coverage in China: Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 144, 104520 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. Regional catastrophic health expenditure and health inequality in China. Front. Public Health 11, 1193945 (2023).

Sheng, G. X. et al. Meta-integration of disease experiences in patients with liver cirrhosis. China Nurs. Manag. 22(12), 1826–1831 (2022).

Valery, P. C. et al. Higher levels of supportive care needs are linked to higher health service use and cost, poor quality of life, and high distress in patients with cirrhosis in Queensland, Australia. Hepatol. Commun. 7(3), e66 (2023).

Tandon, P. et al. Sarcopenia and frailty in decompensated cirrhosis. J. Hepatol. 75(Suppl 1), S147–S162 (2021).

Tian, G. L., He, W. Y. & Chen, Z. Y. Summary of the best evidence for exercise interventions in patients with cirrhosis and sarcopenia. Chin. Nurs. Educ. 20(12), 1493–1499 (2023).

Carey, E. J. et al. A North American expert opinion statement on sarcopenia in liver transplantation. Hepatology 70(5), 1816–1829 (2019).

Jamali, T. et al. Outcomes of exercise interventions in patients with advanced liver disease: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 117(10), 1614–1620 (2022).

Aamann, L. et al. Physical exercise for people with cirrhosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12(12), CD12678 (2018).

Pilcher, J. J. & Bryant, S. A. Implications of social support as a self-control resource. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 10, 228 (2016).

Richard, A. et al. Loneliness is adversely associated with physical and mental health and lifestyle factors: Results from a Swiss national survey. PLoS One 12(7), e181442 (2017).

Tandon, P. et al. Exercise in cirrhosis: Translating evidence and experience to practice. J. Hepatol. 69(5), 1164–1177 (2018).

Johnston, H. E. et al. The effect of diet and exercise interventions on body composition in liver cirrhosis: A systematic review. Nutrients 14(16), 3365 (2022).

Liu, Y., Ji, F. & Nguyen, M. H. Sarcopenia in cirrhosis: epidemiology, diagnosis, management and prognosis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 39(3), 131–139 (2023).

Hui, Y. et al. The relationship between patient-reported health-related quality of life and malnutrition risk in cirrhosis: an observational cohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 130(5), 860–867 (2023).

Vaccaro, J. A., Gaillard, T. R. & Marsilli, R. L. Review and implications of intergenerational communication and social support in chronic disease care and participation in health research of low-income, minority older adults in the United States. Front Public Health 9, 769731 (2021).

Bustamante, A. V., Vilar-Compte, M. & Ochoa, L. A. Social support and chronic disease management among older adults of Mexican heritage: A U.S.-Mexico perspective. Soc. Sci. Med. 216, 107–113 (2018).

Yang, G. & D’Arcy, C. Physical activity and social support mediate the relationship between chronic diseases and positive mental health in a national sample of community-dwelling Canadians 65+: A structural equation analysis. J. Affect Disord. 298(Pt A), 142–150 (2022).

Greenwood, D. A. et al. A systematic review of reviews evaluating technology-enabled diabetes self-management education and support. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 11(5), 1015–1027 (2017).

Wang, T. et al. Effectiveness of disease-specific self-management education on health outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ. Couns. 100(8), 1432–1446 (2017).

Guo, L. et al. Effects of empowerment education on the self-management and self-efficacy of liver transplant patients: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 22(1), 146 (2023).

Lucey, M. R. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11(5), 300–307 (2014).

Addolorato, G. et al. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Transplantation 100(5), 981–987 (2016).

Li, P. et al. Association between daily internet use and incidence of chronic diseases among older adults: Prospective cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e46298 (2023).

Li, S. Y. et al. Construction and application of a comprehensive exercise rehabilitation nursing program for elderly frail patients with liver cirrhosis. Chin. Nurs. J. 58(20), 2437–2445 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Thank all the patients with liver cirrhosis who participated in this study for cooperating with the questionnaire survey and body index measurement, and thank all the medical staff in the Department of Infectious for their support for this study.

Funding

This work was supported by a project funded by the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Department Fund (Qiankehe Support [2021] General 049).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. and L.Y.X. were responsible for formal analysis and editing of the manuscript; Q.L. was responsible for data collection and research; X.Y.Z. was responsible for literature search; M.D.L. and Y.L.X. were responsible for study conceptualization and design; M.D. and F.Z. were responsible for definition of intellectual content; Y.S.S. was responsible for manuscript preparation; J.T.S. was responsible for critical intellectual content of the manuscript critical revision; P.Y. was responsible for the overall integrity of the study, the conceptualization and design of the study, and the integrity of the manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University on December 31, 2021, with the approval number: (KLLY-2021–149).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Xiao, L., Liu, Q. et al. The mediating role of social support in self-management and quality of life in patients with liver cirrhosis. Sci Rep 15, 4758 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81943-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-81943-5